TWO

Wayward Wives

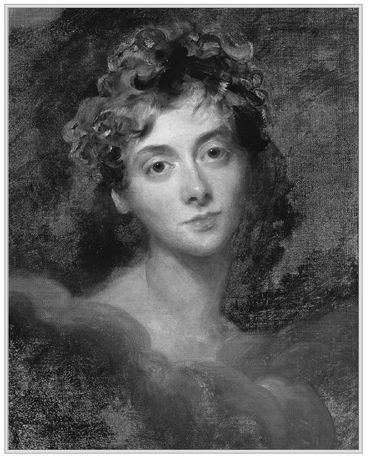

Émilie du Châtelet

1706-1749

When I add the sum total of my graces, I confess I am inferior to no one.

—ÉMILIE DU CHÂTELET TO VOLTAIRE

Émilie du Châtelet was regarded as one of the most beautiful and brilliant women of the Enlightenment, even by her enemies; but for more than two centuries she was better known for being Voltaire’s mistress. “Judge me for my own merits,” she once protested. “Do not look upon me as a mere appendage to this general or that renowned scholar.” Few women of the period could write, much less conduct experiments in physics, chemistry, and mathematics, compose poetry, and translate Greek and Roman authors into French with ease as she did. Her work contributed to energizing the school of theoretical physics in France. She would have been extraordinary in any era, let alone the one she was born in. In her lifetime, she fought for the education and publication that she craved, but struggled under the burdens of society’s expectations for women of her class.

Gabrielle-Émilie Le Tonnelier de Breteuil grew up in the lap of luxury surrounded by servants in a three-story town house near the Tuileries gardens. She was doted on by her father, who encouraged her in her studies, refusing to let her mother send her to a convent. He made sure that she had the same education as her brothers, including fencing and riding lessons along with Latin, Italian, Greek, and German. She was so precocious that her father enjoyed showing her off to his intellectual friends. Her mother despaired at having such an unnatural daughter who refused to appreciate proper etiquette. But Émilie had a hunger for learning that just couldn’t be quenched with talk of fashion and gossip. When her father’s income shrank, and there was no money for new books, Émilie used her mathematical skills at the gaming tables to get her fix.

Tall and clumsy as a child, Émilie seemed destined for spinsterhood. Her father worried that “no great lord will marry a woman who is seen reading every day.” But suddenly at the age of fifteen, she grew from an ugly duckling into a swan. Although she was almost a giant at five foot nine in era when even most men were an average height of five foot six, she was also blond with a supermodel figure and a face that could launch a thousand ships. Raised away from court, Émilie took joyous delight in everything, and soon bets were being made by the court rakes to see who could seduce her first. Émilie nipped that idea in the bud the day she verbally fenced with a colonel with consummate skill. This display of her rapier wit served to keep the rest at bay. They soon turned their attentions elsewhere.

Émilie went husband hunting with a vengeance. She had a laundry list of requirements: he had to be older, of higher rank, and he had to be content that she was beautiful and bright since her dowry was pathetic. She found him in the marquis Florent-Claude du Chastellet,

4 who was twelve years older, a career soldier from one of the oldest families in Lorraine, who preferred wars to court. Out of all of her suitors, he was the only one that Émilie felt she could tolerate. The marquis promised not to interfere with her studies, and Émilie promised to turn a blind eye to his infidelities. They were married on June 25, 1725, at Notre Dame. The story goes that the bride halted the ceremony to correct the clergyman’s pronunciation of a Latin phrase.

After bearing three children, Émilie was bored out of her mind. She moved to Paris to pursue her studies further while her husband stayed in the country. She hired the best tutors in math and physics from the Sorbonne, studying like a fiend. Since women weren’t allowed at Gradot’s, the “in” coffee shop for the scientific crowd, Émilie donned breeches and a frock coat to talk shop with her peers. The proprietors pretended they didn’t notice. Émilie still made time for high society, but she did it her way, dripping in diamonds and wearing gowns of gold and silver cloth, normally reserved for royalty, that were cut low enough to show off rouged nipples. She chatted happily about Descartes to her throngs of admirers. She held a salon in her newly renovated town house, decorated tastefully but expensively. When she ran out of money for the renovations, she gambled until she’d won enough to continue.

Once she’d given her husband an heir, Émilie indulged herself in a love affair with the duc de Richelieu.

5 The duke was rich, powerful, and extremely handsome; men wanted to be him, and women threw themselves at his feet. Émilie was a different kettle of fish. He fell for her because he liked to talk to her. She was witty and chattered a mile a minute about the things she loved, mainly science and the theories of John Locke. The affair didn’t last long, as the duke couldn’t be faithful to anyone, and the very qualities that made Émilie different began to pall after a while. Still, they managed to end their affair with dignity and remain friends.

Émilie yearned for a man who could satisfy her both intellectually and sexually. She found him in Voltaire. They were introduced by mutual friends in 1733 after Voltaire’s return from a long exile in England. Already he was famous for his plays and poems and his ability to get into trouble. It was the coming together of two geniuses who defied social conventions. They were immediately attracted to each other and became lovers soon after they met. “Why did you reach me so late? What happened to my life before? I hunted for love but found only mirages,” he wrote to her. They broke the conventionally accepted rules of adultery, showing their affection in public, romping indiscreetly all over the city.

They made an odd couple. Not only was Émilie a head taller than her lover but she was twenty-six and Voltaire was thirty-nine. Voltaire had finally found a woman who was intellectually his equal, although his superior in rank, and who respected and adored him. Émilie finally had a man who respected her brain as well as her body. He was also one of the few men rich enough to afford her expensive tastes. Voltaire taught her how to speak English so that they could converse without anyone understanding what they were talking about. She read his work and gave him gentle criticisms.

Not long after they met, they moved into the Château Cirey, a tumbledown mansion owned by Émilie’s husband in the country between Champagne and Lorraine. The move was precipitated by Voltaire getting into trouble again for his radical political views. For the next fifteen years, they lived there together, embroiled in a private world of intense intellectual activity intertwined with romance. Émilie described their life at Cirey as “Paradise on Earth.” Voltaire lent the marquis forty thousand francs to pay for renovations to make the château livable, including a tub for Émilie’s daily baths. Playing architect, Émilie installed a kitchen inside the château, a novel idea at the time. They quickly amassed a library of twenty-one thousand volumes, more than in most universities in Europe. The marquis was happy with the renovations because the restored house gave him a place to hunt. His visits also gave their affair an aura of respectability. The marquis was not a jealous man. Since Émilie had no objections to his affairs, he refused to meddle in hers.

The château became something like a modern-day think tank. Émilie and Voltaire entertained some of the best minds from Paris, Basel, and Italy, including her former lover Pierre Maupertuis, Francesco Algarotti, and Clairaut, hailed as France’s new Isaac Newton, who at first came to scoff, but then hung around, impressed by what they saw. Visitors to the château were only entertained in the evenings since Émilie typically put in twelve to fourteen hours a day at her work. She had taken over the great hall as a physics lab, testing Newton’s theories with wooden balls hanging from the rafters. Eventually the hall became so cluttered that it was an impenetrable maze. Émilie had prodigious energy, often sleeping only three or four hours a night. When she was on a deadline, she plunged her hands into bowls of cold water to stay awake.

Rooms were dimly lit and the curtains were shut, the better for mental stimulation. Guests were expected to entertain themselves. Dinner was at no set time, just when Émilie and Voltaire decided they were hungry. Émilie would arrive at the dining room table powdered and perfumed and dressed as if at a court ball, dripping in diamonds, her fingers stained with ink. Guests served themselves from the dumbwaiters. Conversation was fast and furious as the lovers discussed what they were working on or argued mathematical equations. After dinner it was back to work. Late at night, they would put on plays in the little theater or Émilie would play the pianoforte and sing entire operas. There would be poetry readings at 4:00 a.m. or picnics in the middle of winter.

Émilie and Voltaire decided to collaborate on a major project: a treatise on the works of Newton, covering the entire spectrum of his philosophical, scientific, and mathematical studies. When word first leaked, all of Paris ridiculed the idea. But when it was finally published after two years of work, Émilie had the last laugh. It was hailed as a masterpiece by every scientist of note. Although Voltaire’s name was on the cover, he acknowledged her as coauthor. She was recognized as a woman of powerful intellect and finally treated with the respect that was due her. The Elements of Newton’s Philosophy was so influential that it persuaded the French to abandon the theories of their national hero, René Descartes, and jump on the Newton bandwagon.

Now Émilie made the most unorthodox decision of her life: to submit an essay to the Royal Academy of Sciences yearly competition. This year the theme was fire. Émilie had been helping Voltaire with his essay but she felt that his conclusions were wrong. Her thesis was that light and heat were the same element while Voltaire believed the opposite. She had an unfair advantage since she knew what Voltaire had written. In two weeks she wrote her essay, 139 pages long. She didn’t tell Voltaire that she was entering, although she did tell her husband; she needed his permission to enter. She submitted her entry anonymously, wanting it to be judged on its own merits. Neither Voltaire nor Émilie won, but he later persuaded the academy to publish her paper under her own name. It was the first time the academy had ever published a dissertation by a woman.

In her spare time, when she wasn’t conducting science experiments or learning advanced calculus, Émilie wrote poetry, translated Latin and Greek classics, and mastered law to defend her husband’s interests at court. For fun, she wrote one of the first self-help books, entitled Discourse on Happiness, which went through six editions. In it, Émilie taught women how to be as happy as she was. She advised them to cultivate “strong passions,” enjoy sex, enrich their minds through education, and make themselves mistresses of the “metaphysics of love.” Émilie translated the book into English herself and it was also translated into Dutch and Swedish.

But the idyll couldn’t last. Voltaire fell out of love first. It was hard living with a genius, particularly one who was almost always right. He had taken up history and given up science, realizing that Émilie was far ahead of him intellectually in that field. “I used to teach myself with you,” he wrote, “but now you have flown up where I can no longer follow.” Émilie grew tired of having to tend to his ego, when she wanted to do her own research; and she became upset over the time Voltaire spent at the court of Frederick the Great of Prussia, whom she didn’t like or trust. They both found solace in other lovers. Voltaire secretly began having an affair with his widowed niece Madame St. Denis. Émilie fell in love with the poet and soldier Jean François de Saint-Lambert, who was ten years younger. Their relationship eventually dwindled into a loving friendship. Although no longer lovers, they couldn’t do without one another. No one understood them as well as each other.

At the age of forty-two, she found herself inconveniently pregnant. The relationship with Saint-Lambert petered out at the news. Voltaire, however, stayed by her side and her husband graciously offered to accept paternity. In a letter to a friend she confided her fears that, because of her age, she would not survive her confinement. During her pregnancy she moved into a suite at Versailles, where she redoubled her efforts to finish her book on Newton’s Principles of Mathematics, staying up until the wee hours of the morning. She finished the book a few days before she went into labor in September. Émilie bore the child, but died six days later from an embolism. The child, a daughter, soon died as well.

Voltaire was distraught: “I’ve lost the half of myself—a soul for which mine was made.” Months after her death, his servant Longchamps would find him wandering through the apartments that he had once shared with Émilie in Paris, plaintively calling her name in the dark. He helped to prepare Émilie’s book, called The Principles of Mathematics and Natural Sciences of Newton, for publication. It came out ten years after her death, just in time for the return of Halley’s comet, which stimulated a burst of interest in Newton. To this day it is still considered to be the standard translation of Newton in French, a lasting testament to the woman Voltaire described as “a great man whose only fault was being a woman.”

Lady Caroline Lamb

1785-1828

I fear nobody except the devil, who certainly has all along been very particular in his attentions to me.

—LADY CAROLINE LAMB

Lady Caroline Lamb famously remarked about the poet Byron that he was “mad, bad, and dangerous to know.” By the time their affair ended nine months later, Byron was the one crying for mercy. “Let me be quiet. Leave me alone,” he wailed in a letter to her, sounding unlike the hardened womanizer that he was. Even the rather louche Regency society was scandalized by her reckless behavior and flouting of convention.

The only daughter of the Earl and Countess of Bessborough, she was born in November 1785. Caroline came from a family noted for its eccentric, strong-willed, and scandalous women but she would surpass them all. Her aunt, the beautiful and glamorous Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, lived in an unorthodox arrangement with her husband and his mistress, who happened to be her best friend. Caroline’s mother occupied her time with her lover Lord Granville and fending off the playwright Sheridan.

Caroline had a chaotic upbringing, alternately running wild with her cousins at Devonshire House or restrained during her stay with her grandmother, the austere Lady Spencer. From early childhood, Caroline showed a vivid and volatile nature, high-spirited and fearless. She was also nervous and hyperactive, asking questions incessantly, sometimes the same question over and over again even after it had been answered, and getting on everyone’s last nerve. To calm her down, she was given liquid opium. While most kids outgrow the inclination to say whatever comes into their heads, Caroline never did.

In 1805 Caroline married William Lamb, heir to Viscount Melbourne, after a three-year courtship. At the reception, Caroline broke into tears at leaving her family and had to be carried out by William to the waiting carriage. It was a sign of things to come. The couple was forced to move in with his family, occupying the upper floor of the mansion in Whitehall, because William’s father refused to increase his allowance after their marriage. It was an uneasy fit. While her family was sophisticated and tolerant, the Lambs were a rowdy, boisterous family devoted to practical jokes. They made fun of her and jeered at William’s devotion to his wife. His sister Emily in particular took against her and did her best to come between them.

If living with her in-laws wasn’t bad enough, it was soon clear that the couple was incompatible. Darkly handsome, William was easygoing, with a mocking smile and an air of cultivated bored indifference. Caroline, on the other hand, was high-strung and childish. Although William loved her, he was also reserved, unable to give Caroline the petting and coddling she desired. He soon set about disabusing her of what he thought of as her old-fashioned notions, in particular her belief in God. She once remarked that William “amused himself with instructing me in things I need never have heard of or known.” The physical side of marriage shocked Caroline as well, who probably had learned very little about sex before she was married.

After suffering two horrible miscarriages, Caroline finally gave birth to a son, Augustus, in 1807. Unfortunately, it soon became apparent that he was not only mentally handicapped but suffered from epilepsy as well. Caroline refused to send him away, ignoring the pleas of her family and her in-laws. Despite his affliction, she was devoted to him, but there would be no more children.

As her husband spent more time away from home on parliamentary business, Caroline grew bored and resentful. To provoke him and to be noticed, she wore risqué dresses cut almost to the nipple and flirted outrageously. Her behavior caused comment. “The Ponsonbys are always making sensations,” one caustic observer wrote, referring to Caroline’s family. She had a brief, publicly flaunted affair with Sir Godfrey Webster. Lady Melbourne was appalled, not because of the affair, but because Caroline committed the cardinal sin of being indiscreet. Not only did she accept jewelry and a puppy from Webster, but she also confessed the affair to her husband, who forgave her. She later admitted, “I behaved a little wild, riding over the downs with all the officers at my heels.”

In March 1812, Caroline read an advance reading copy of Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage and wrote him an anonymous fan letter. Her friend Samuel Rogers told her that Byron had a club foot and bit his nails but she replied, “If he is as ugly as Aesop, I must see him.” Byron at this time had yet to become the rock star of the Regency that he was soon to be. He’d had some verses published in 1806 and 1807, but Childe Harold made his reputation after the first two cantos were published. Caroline wrote him an anonymous poem in iambic pentameter à la Childe Harold.

Byron later described Caroline to a friend as “the cleverest, most agreeable, absurd, amiable, perplexing, dangerous, fascinating little being that lives now or ought to have lived two thousand years ago.” Caroline was beautiful and charming but, in the words of one of her friends, “had a restless craving after excitement.” Byron received hundreds of what were essentially fan letters from women. But when he received Lady Caroline’s poem, he was impressed, particularly when he discovered that the anonymous writer was the aristocratic and eccentric Lady Caroline Lamb. When she first saw him at a party at Lady Westmorland’s, surrounded by beautiful women, she turned on her heel and declined to be presented, which intrigued the poet. That night in her journal she wrote, “That beautiful pale face will be my fate.”

Soon after, while out riding, she placed an impromptu call on Lord and Lady Holland. When she was told that Byron was expected as well, she protested that she couldn’t meet him dusty and disheveled. She ran upstairs to freshen up and when she came downstairs, Byron was entranced by the elfin creature before him, with her bobbed golden curls and boyish figure. Bending toward her, he whispered, “The offer was made to you before. Why did you resist it?”

She couldn’t resist it now. What followed was an affair that lasted only nine months, but the repercussions continued for years. Caroline was totally besotted with Byron and, initially, he was equally smitten by her, although she wasn’t his usual type; he normally preferred voluptuous, uncomplicated women. It was not just a sexual attraction but also an intellectual attraction. They shared a love for dogs, horses, and music. They wrote constantly to each other, sometimes every day. By the end of their affair, around three hundred letters had exchanged hands.

The public nature of the romance presented no problem to Caroline. Most of her family, including her mother-in-law, had little regard for fidelity, but they kept their liaisons quiet. This was not Caroline’s style. She enjoyed making scenes, and with Byron, there was ample opportunity. Caroline didn’t care about other people’s opinions, a trait that Byron admired. She also had no use for the hypocrisy of the times, where as long as one was discreet, one could get away with anything. At first Byron was charmed by her enthusiasm, but eventually he got bored. He preferred the chase. As he summed it up, “Man’s love is of man’s life a thing apart, / ’Tis woman’s whole existence.” On the other hand, he also wanted all her love and devotion solely for him. It killed him when Caroline admitted that she loved her husband, and that she wouldn’t tell him that she loved him more than William. The more he demanded of her, and the more she gave, the less he wanted her once the initial thrill was gone.

Byron soon pulled back, wounding Caroline, who wanted him to admit that the relationship mattered to him. Her infatuation became obsessive. She begged to be invited to suppers where she knew he was going to be. If she wasn’t invited, she would wait in the garden. She made friends with his valet, in order to gain admittance to his rooms in St. James, where she rifled through his letters and journals. Hostesses began ridiculing her behind her back, as they smugly gossiped over tea.

His friends advised him that his affair with Caroline was ruining his reputation. He removed himself to his country estate, where Caroline bombarded him with letters he didn’t answer. But Caroline persisted. She became that woman we all fear becoming, the crazy ex-girlfriend, unable to walk away with her dignity intact when it was clear that he was no longer interested. She sent him some of her pubic hair tinged with blood and dressed herself in a page costume to smuggle herself into his rooms. The campaign was so intense that Byron would refuse to attend social engagements for fear of meeting her. Byron’s passive-aggressive behavior didn’t help matters. He couldn’t—or wouldn’t—just end things. And William refused to play the outraged husband and demand she end the affair.

Byron detested “scenes” unless he was the one making them and he finally found the intensity all too much. He eventually broke off the affair, but Caroline wouldn’t give up. She claimed that she and Byron intended to elope. Her father-in-law called her bluff, telling her, “Go and be damned! But I don’t think he’ll take you.” Caroline ran off, her family panicked, and her mother had a stroke. It was left to Byron to bring her back, but she would only go after William promised to forgive her. Her parents eventually whisked her off to Ireland, where Caroline tried to forget Byron and repair the damage to her marriage.

While she was gone, Byron took up with Lady Oxford, an older woman with six children, who was also a friend of Caroline’s. Lady Oxford encouraged her lover’s disdain for Caroline, effectively ending their friendship. When Caroline wrote to Byron from Ireland, he would compose his replies to her with Lady Oxford’s help. As she was arriving back in London, she received a letter from Byron, sealed with Lady Oxford’s initials, that read: “I am no longer your lover; and since you oblige me to confess it, by this truly unfeminine persecution,—learn that I am attached to another; whose name it would be of course dishonorable to mention.”

The shock made Caroline physically ill; she lost weight, and her behavior became increasingly erratic. During Christmas, she held a dramatic bonfire at Brocket Hall. While village girls danced in white, Caroline threw copies of Byron’s letters into the fire, while a figure of the poet was burned in effigy. She forged a letter from Byron to his publisher, John Murray, in order to take possession of a portrait of him that he had long refused her. She would visit at inappropriate hours, once leaving a note in one of his books on his desk: “Remember me!”

At a party at Lady Heathcote’s, as they exchanged barbed remarks about dancing the waltz, suddenly Caroline took a knife and slashed her arms. Horrified guests tried to stop the bleeding; someone offered a glass of water. Caroline broke the glass and tried to gash her wrists with the slivers. Finally Byron felt the only way to truly end Caroline’s obsession was to tell her that not only had he slept with his half sister Augusta but that he’d also had affairs with men, hoping to turn her desire to disgust.

The nineteenth-century term for what ailed Caroline was “erotomania,” dementia caused by obsession with a man. More likely Caroline was bipolar. Nowadays, she’d be given Prozac or lithium to balance out her moods, but back then the only treatment was laudanum, a concoction derived from opium and alcohol. It was used for everything from menstrual cramps to nervous ailments, from colds to cardiac diseases. The problem was that it was also addictive. Caroline began to use laudanum and alcohol indiscriminately to ease her nerves and the sting of Byron’s betrayal.

Byron married Lady Melbourne’s niece Annabella Milbanke in 1815, but after their first child was born, a daughter named Ada Augusta, the couple separated in 1816. Caroline at first was on Team Byron, writing to him, urging him to reconcile with his wife or to give her a large settlement so that a scandal could be avoided. If Caroline was hoping for a big thank-you from Byron, she was mistaken. All bets were off when she learned from John Murray that Byron had been so violent and cruel that Annabella feared for her life. Caroline swore to have no more communication with Byron. She also informed Annabella that he had confessed to an incestuous relationship with Augusta at their last meeting, although she begged Annabella not to tell Byron that she was the one who told her. When Annabella spread the word, Byron was forced to leave England.

Caroline got her own revenge of a sort in 1816 with the publication of her novel Glenarvon, a thinly disguised account of her relationship with Byron. She even quoted one of his letters in the novel. A gothic melodrama, her husband, William, also appears in it as the heroine’s cynical husband who destroys his young wife’s faith, while Byron is the hero/villain accredited with every crime from murder to incest to infanticide. The roman à clef also satirized the Holland House set so perfectly that twenty years after the book appeared, friends still called Lady Holland the Princess of Madagascar, after the character modeled on her, behind her back. Although the book was published anonymously, the ton were aware of the author and began to shun her. To Caroline’s delight and everyone else’s dismay the book sold out. When Byron heard the news, he told his publisher John Murray, “Kiss and tell, bad as it is, is surely somewhat less than f*** and publish.”

The reviews of Glenarvon were encouraging enough for Caroline to continue to write, but the only opinion that she cared about was Byron’s. She took other lovers but they could never replace Byron in her heart. The affair made her life afterward seem dull by comparison. In 1820, she appeared at a masquerade ball dressed like Don Juan, after the first cantos of Byron’s now classic poem had been published. Four years later, she had a nervous breakdown after accidentally encountering Byron’s funeral cortege as it passed through Welwyn, near Brocket Hall. As her health declined, she began abusing alcohol and laudanum and gave up regular meals and all semblance of order.

William’s parents had encouraged him for years to formally separate from Caroline for the good of his career. They had even gone so far as to try and have her committed. However, every time he took steps to do so, they would reconcile. Despite her bad behavior, he continued to love her, although her tantrums and affairs took a toll on him. Finally in 1825, after William dithered about the separation one too many times, his sister Emily viciously and aggressively attacked Caroline, threatening a public trial. Caroline agreed to the separation.

By 1827, she was an invalid, under the full-time care of a physician. William had been given the post of Secretary for Ireland and was away when she took a turn for the worse. Despite the past, he was still devoted enough to her that he came back from Ireland in inclement weather to be by her side when she died on January 26, 1828. She was only forty-two years old. After her death, William never remarried. He told Lady Brandon, soon to become his mistress, that he felt “a sort of impossibility of believing that I shall never see her countenance or hear her voice again.”

Jane Digby

1807-1881

Being loved is to me as the air that I breathe.

—JANE DIGBY, WRITING TO KING LUDWIG OF BAVARIA

Jane Digby was born into an aristocratic family with every conceivable advantage—beauty, money, and privilege—yet she shocked her upper-class world by collecting husbands and lovers like a nineteenth-century Angelina Jolie before ending up in the arms of a desert prince. She had uncanny powers of fascination, luring men with her wit and charm. In her lifetime, no fewer than eight novels were written about her, most of them unflattering portraits. Cutting free from tight-laced English society in exchange for the life of a passionate nomad, she spent her life searching for that one perfect love.

Born in 1807, Jane was much loved and spoiled by her parents and relatives, who hated to discipline their golden-haired little darling. From childhood, Jane showed the reckless courage, independence, and taste for adventure that marked her ancestors, once wandering off with a band of gypsies because she liked their lifestyle. Jane’s delicate beauty of blond ringlets, violet eyes, and creamy complexion was noticed at a very early age, as well as her power to attract the attention of men. It was her beauty that convinced her mother that it was prudent to get her married off as soon as possible.

At her coming-out ball, Jane met Edward Law, Baron Ellenborough. He was seventeen years her senior and a widower. On paper, it seemed a brilliant match. Ellenborough was a rising politician, handsome, and rich, and his maturity would curb her childish impulses. Flattered by the attentions of an older, experienced man, Jane accepted his proposal. She had visions of the grand life she would lead, the London house, the balls and parties, taking her place as a leading political hostess. On his part, Ellenborough was looking for two things: a decorative partner and an heir. After a short courtship, they were married by special license.

The old adage “Marry in haste, repent at leisure” could have been written about Jane’s first marriage. No sooner had they shaken the rice out of their shoes than Jane realized why her husband had been called “Horrid” Law at school. Ellenborough was ambitious and totally devoted to his career. He thought nothing of spending long hours at the House of Commons late into the night, writing speeches, and hanging out with his political cronies. Instead of attention and affection, he gave her jewelry, cold diamonds that wouldn’t keep her warm at night. Not only did Jane have to contend with the memory of his late wife, she soon discovered he had a mistress tucked away in Brighton.

Jane was not a woman who could live without love and passion in her life. If her husband was not willing to give it to her, she would look elsewhere. Dressed in décolleté gowns, Jane fell in with the glittering and sophisticated international society set led by Princess Esterházy. She soon found her cousin George more than willing to console her. When Jane found herself pregnant, she passed the baby off as her husband’s. When her cousin finally dumped her rather than risk his career, Jane moved on to her grandfather’s librarian. He later wrote that she had “blue eyes that would move a saint, and lips that would tempt one to forswear heaven to touch them.”

It was at one of Almack’s famous Wednesday night balls in late May 1828 that Jane, newly turned twenty-one, met the darkly handsome and courtly Prince Felix Schwarzenberg, an Austrian diplomat who had just been posted to London. The prince was instantly smitten and laid siege to her heart with flowers, poems, and presents until she succumbed to his ardor. It was more than a physical attraction for Jane. The prince had an air of mystery; he literally oozed adventure with his talk of the faraway places he had seen. Jane fell madly, ecstatically in love with him and didn’t care who knew it, practically shouting it from the rooftops. Jane would visit him at his flat on Harley Street, wearing a veil to hide her identity, but before long they became reckless. She was seen by a neighbor in Schwarzenberg’s embrace, the prince lacing up her stays. Soon the gossip about them was so flagrant that Schwarzenberg was sent packing back to the continent before his career was totally ruined.

When Jane realized she was pregnant, she decided to risk everything by joining her lover on the continent. Her parents pleaded with her to at least attempt to repair her relationship with her husband. Her father, in particular, tried to impress upon her what she was giving up by leaving him to go abroad. If she stayed in England, and they formally separated, she could still take her place in society after a suitable amount of time. But Jane was not to be denied. As far as she was concerned, her life and her fate lay with the prince. He was the only man she wanted to be married to.

When Ellenborough found out about the affair, he decided that the only hope he had of maintaining his career and saving his honor was to divorce her. The divorce case was so sensational that for the first time, the Times of London featured the story on its front page instead of among the classified advertisements that were a mainstay of the paper until the 1960s. Despite the fact that he was the “innocent party,” Ellenborough was chastised for allowing his wife to associate with “undesirable persons.” In exchange for Jane not introducing evidence of his own indiscretion in court, Lord Ellenborough settled a generous sum on her for the rest of her life.

While the divorce proceeded in England, Jane gave birth to Schwarzenberg’s daughter. The prince soon proved to have feet of clay. Schwarzenberg’s family was adamant that he break up with her. The family was Catholic and marriage to a now notorious divorcée would be ruinous. Realizing that he was out of his depth and fearing for his career, Schwarzenberg left her for good.

On the rebound, Jane fled to Munich and into the arms of King Ludwig I of Bavaria, who was captivated like many men before him by her beauty and intelligence. Her portrait joined the pantheon of other beautiful women in his “Gallery of Beauties.” She also caught the attention of Baron Karl von Venningen-Üllner, who worshipped her and pursued her relentlessly while she pined for Felix. After months of rebuffing him in the hopes that Felix would return to her, she finally succumbed to his attentions and promptly became pregnant. Although she didn’t love Karl, Jane succumbed to pressure from her parents, the baron, and the king to get married, but not before giving her daughter by Schwarzenberg to his sister, where she grew up with no memory or knowledge of her beautiful mother.

For a time she was content, but her husband wanted to turn her into a German hausfrau in the country, while Jane was lively and intelligent and loved parties. Even a second baby couldn’t tie Jane down. At a ball, during Oktoberfest, Jane met a young Greek count named Spiridon Theotoky, who awakened her sleeping passion. He was young and carefree, the antithesis of her sober and conservative husband. When the lovers tried to elope, her husband followed them and challenged the count to a duel. Although Theotoky was wounded, he managed to survive. Despite his hurt and humiliation Karl generously agreed to release Jane from their marriage. He received custody of their children, and he and Jane stayed friends for the rest of her life.

Jane moved to Greece and married her count, converting to the Greek Orthodox faith. They had a child, Leonidas, who became Jane’s favorite, the only one of her five children that she felt any affection for. It seemed as if Jane had finally met her soul mate, until the family moved to Athens and Spiridon began drinking and spending his nights out. After fifteen years together, she discovered that not only was he unfaithful, but he was also stealing from her accounts, so she left him. No sooner had she settled into a new home, when she suffered the devastating loss of her six-year-old, Leonidas, who died falling from a balcony when he tried to slide down the railing to greet her.

Jane, beside herself with grief, believed it was a punishment for her actions. Leaving Greece, she wandered disconsolately around the Mediterranean. For a time she became the mistress of an Albanian general and was thrilled to share his rough outdoor life as queen of his brigand army, living in caves, riding fiery Arab horses, and hunting game in the mountains for food—until she found that he, too, was unfaithful, with her maid, no less, and left him on the spot.

Now middle-aged but still stunningly beautiful, and vowing to renounce men, she headed for Syria, to see Damascus. Speaking Turkish, dressed in a green satin riding habit, she hired a Bedouin nobleman, Sheikh Medjuel el Mezrab, who was twenty years her junior, to escort her. Smitten by her courage and zest for life, Medjuel proposed but Jane wasn’t interested. On her second trip to Damascus, she began to see him in a different light. When he proposed again, she asked for only two things: that he divorce his wife and that he remain faithful to her. Despite the advice of the British consul and her family, she threw caution to the wind. At the age of forty-six, she had finally found the great love of her life. Medjuel gave her the love and devotion that she had been longing for, and an adventurous life among the Bedouin.

Jane made one last visit to England in 1856. She found English society rigid and straitlaced under the reign of Victoria and Albert. They found her shocking; not only had she married an Arab but she also had three ex-husbands who were still living! Jane realized just how far she had moved away, not just physically but mentally. Victorian England was no place for her. After six months, she kissed her family good-bye and returned to Medjuel and the desert.

During the remainder of her life she adopted for six months of each year the exotic but uniquely harsh existence of a desert nomad living in the famous black goat-hair tents of Arabia; the remaining months she spent in the splendid palace she built for herself and Medjuel in Damascus. Accepting Arab customs, although she never converted to Islam, she dressed in traditional robes, her blond hair dyed black. As wife to the sheikh and mother to his tribe she found genuine fulfillment. She learned to milk camels, she hunted, she rode into battle at Medjuel’s side during the frequent intertribal skirmishes, and she raised Thoroughbred horses. Diplomats and scholars came to visit her, regarding her as an authority in the area. Middle Eastern expert and adventurer Sir Richard Burton called her the cleverest woman he’d ever met.

With her husband by her side, she passed away at the age of seventy-four. Obeying her final wishes, he had her buried in the Protestant cemetery in Damascus. Then her grief-stricken widower rode out into the desert and sacrificed one of his finest camels in her memory.

Jane Digby’s worst sins were an overwhelming hunger for love and adventure, and an astonishing naiveté about men. Despite her romantic disappointments, she never allowed herself to become bitter or jaded. She always believed that the perfect lover was out there, one who would fulfill her body and soul. Some historians and biographers have regarded Jane as promiscuous or a nymphomaniac. But Jane was a serial monogamist. In every relationship, she gave her full heart; each time she was sure that she had found “the one.” She could never be content with maintaining the discreet appearance of respectability. Jane also had a healthy sexual appetite in an era when women weren’t supposed to enjoy sex. If she had been a man, she would have been admired and patted on the back.

Jane lived a remarkable life but she paid a high price for the choices she made, ostracized by most of her relatives and polite society and alienated from her children. She saw her name become a byword for scandal. Despite all this, Jane was able to look back on her life with no regrets. She had lived fully and loved.

Violet Trefusis

1894-1972

Across my life only one word will be written: “waste”—waste of love, waste of talent, waste of enterprise.

—VIOLET TREFUSIS

It was to be the wedding of the year. St. George’s Hanover had been booked, the invitations sent, the Times of London had reported on the impressive list of wedding gifts, including a diamond brooch from the king and queen, but London society wondered whether the bride would show up. There was an audible sigh of relief in the church when, wearing a gown of old Valenciennes lace over chiffon, Violet Keppel walked down the aisle on her father’s arm and became Mrs. Denys Trefusis. But before the thank-you notes were written, Violet was back in the arms of her lover. It was a scandal that people could only whisper about behind closed doors. For the lover that Violet Trefusis refused to abandon was another woman: the writer Vita Sackville-West.

There were two great loves in Violet Keppel’s life. The first was her mother, Alice Keppel, known as “La Favorita,” mistress of Edward VII for the last twelve years of his life. Violet and her sister, Sonia, from an early age were in awe of their vivacious and charming mother. Violet once wrote, “I wonder if I shall ever squeeze as much romance into my life as she had in hers.” Violet’s father, the Hon. George Keppel, was a rather shadowy figure in their lives, his chief job to stay discreetly out of the way.

Violet was ten when she met her second great love, Vita Sackville-West, at a party. Although Vita was two years older, they bonded over their mutual love of books and horses. Both also had glamorous, dominating mothers and complacent fathers. The two young girls attended school together and wrote each other when they were apart. Violet, from the beginning, idolized Vita and bombarded her with letters. When Violet was fourteen and Vita sixteen they traveled together to Italy, where Violet had been sent to perfect her Italian. Violet declared her love to Vita and gave her a Venetian doge’s lava ring she had wheedled from an art dealer when she was six. “I love in you what I know is also in me, that is, imagination, a gift for languages, taste, intuition, and a mass of other things. I love you, Vita, because I have seen your soul,” she wrote.

After the death of Edward VII in 1910, the Edwardian era was over and with it Mrs. Keppel’s reign as La Favorita. The new king and his queen ushered in a more conservative age with a less glittering court, at which Mrs. Keppel was not welcome. Practical as always, she took herself abroad as a sort of “discretionary” leave before reentering British society. Violet spent those years in Germany, Italy, and France, developing her fluency for languages.

Violet returned to England in 1913, dressed in the latest Paris fashions, to make her debut. With a glamorous, desired mother, it was difficult for Violet to feel as lovable, good-looking, or successful. Feeling she couldn’t compete with her mother, she determined to be as different as possible. Wanting to be the center of attention, Violet usually managed it with her gift for mimicry, her low, husky voice, and her large gray eyes. She became a terrific flirt, becoming engaged to several men, including the nephew of the Duke of Westminster.

But underneath the gay exterior, Violet was desperately unhappy. She found her mother’s world boring and straitlaced, full of old people talking about old ideas and obligations that she hated but was scared to defy. She had also never forgotten Vita. But their lives had gone in different directions. Vita had gotten married to diplomat Harold Nicolson and settled down to the life of a country matron, giving birth to two boys. She also adored her husband, whom she’d nicknamed “Hadji.”

In April 1918, Violet invited herself to stay with Vita at Long Barn, the Nicolsons’ home in the country, with the excuse that she was frightened by the threat of bombs in London. Vita was not too thrilled; they had seen little of each other during the war, and she thought they might end up bored with each other. Still, it would be impolite to refuse. One night Harold didn’t return from London, staying the night at his club. The two women spent the day together, tramping through the woods; Vita shared her dreams with Violet of being a great writer. She also shared a secret about her marriage: that Harold had contracted a sexually transmitted disease from a man he had had a brief affair with at a country house party. While Vita was initially shocked, she and Harold came to an understanding that they would both be allowed to pursue outside affairs as long as their own bond was paramount. That agreement was soon to be tested. That night, wearing a red velvet dress exactly the color of a rose, Violet once again declared her love, but this time Vita reciprocated. In her diary, which her son Nigel later published as part of his biography of his parents, Portrait of a Marriage, Vita paints Violet as a seductress that she couldn’t resist.

The two women became lovers, going off on holiday together to Cornwall. Emotionally, spiritually, and physically they were now united. It was a raging fire that threatened to torch everything in its path. Violet later wrote, “Sometimes we loved each other so much we became inarticulate, content only to probe each other’s eyes for the secret that was secret no longer.” They pretended to be gypsies and called each other Mitya and Lushka. They spent an increasing amount of time together, much to the dismay of Vita’s husband, Harold. In the autumn of 1918, Vita and Violet began work on Challenge, Vita’s romantic novel about the conflict between love and duty, in which she depicted herself and Violet as the lovers Julian and Eve. Vita took to wearing corduroy trousers; with her short hair, she looked like a man. Harold was incensed at the idea of Vita going off on holidays without him. She wrote him a letter, uncomplimentary toward Violet, telling him that she needed new experiences and horizons but it didn’t dim her love for him.

Gossip about the two women wormed its way into all the smart drawing rooms in London. Mrs. Keppel worried that her eldest daughter was in danger of ruining herself. She had no problem with what people did behind closed doors, but appearances must be maintained. She didn’t understand the new generation, who, having survived a war, had no interest in living as their parents had. Violet was unrepentant despite the gossip that was buzzing through London society. She was obsessed with Vita, spending her days in agony until the next time she could see Vita or would receive a letter from her. She and her mother fought when Mrs. Keppel caught her writing to Vita. “I hate lies,” she wrote to Vita. “I’m so fed up with lies.” Violet’s dream was for Vita to leave Harold and go off to France with her to live openly as a couple.

In the meantime, Mrs. Keppel determined that it was time Violet got married. Society dictated that no matter what one’s proclivities were, one still got married, particularly in the case of upper-class women who depended on marriage for support. Violet had no skills to support herself with independently; her only income was the allowance Mrs. Keppel gave her. No marriage, no allowance.

She even had the perfect candidate in mind, Major Denys Trefusis. The son of an old aristocratic family, he was twenty-eight and attractive, with reddish gold hair and blue eyes. An officer in the Royal Horse Guards, he had served heroically during the war. Awarded the Military Cross for his services during the war, Denys was tall, handsome, kind, and intelligent, with a sardonic wit similar to Violet’s own. Violet met him in London when he was on leave and she had written him lively, chatty letters while he was at the front, seducing him by post.

Mrs. Keppel began actively promoting the match, hoping that marriage would settle her. Violet saw Denys as a way to get her mother off her back and to goad Vita to leave Harold, but she didn’t intend to marry him. Vita, however, hoped that Violet would gain more freedom by marrying. Harold Nicolson, trying to be a good and reasonable husband, suggested that Vita buy a little weekend cottage in Cornwall where she could do whatever she wanted, and he wouldn’t ask questions. This was exactly the type of life that Violet abhorred and wanted nothing to do with, a life of secrets and hypocrisy.

Denys proposed to Violet but she put him off. Instead, she and Vita went off to Paris for ten happy days. They attended the opera, ate in the cafés. They made a striking pair, Violet delicate and feminine, Vita tall with the elegance of a handsome boy. Instead of returning home, they went off to the south of France. In Monte Carlo, they scandalized everyone by dancing together at a tea dance at their hotel. Violet tried to extract promises from Vita that they would stay together indefinitely, threatening to kill herself if she didn’t agree; these scenes would repeat whenever Vita tried to escape. But Vita didn’t try too hard. Harold Nicolson later wrote to Vita, “When you fall into Violet’s hands, you become like a jellyfish addicted to cocaine.” The pair didn’t return for four months.

If Violet wouldn’t save herself, then Mrs. Keppel would do it for her. She sprang into action, demanding that Violet stop dithering and marry Denys. The engagement was announced after Denys agreed to Violet’s condition that the marriage would remain unconsummated. He was genuinely in love with Violet and was prepared to let her have her way. Nigel Nicolson suggests in Portrait of a Marriage that Denys may also have been partially impotent, which would explain why he agreed to her demands, or perhaps he just thought that eventually the affair with Vita would peter out. Violet was in a quandary. Her life was about to become the very thing that she loathed. She wrote to Vita, panic-stricken, “Are you going to stand by and let me marry this man? It’s unheard of, inconceivable. You are my whole existence.”

On the day of her wedding, she wrote to Vita, “You have broken my heart, goodbye.” Vita went off to Paris with Harold to keep herself from stopping the wedding. The marriage was doomed from the beginning. The newlyweds went to Paris for their honeymoon and ran smack into Vita and Harold. Vita met Violet at the Ritz, where they resumed their relationship. “I treated her savagely. I had her. I didn’t care, I only wanted to hurt Denys,” Vita wrote later. She promised Violet that in the autumn they would go away together. The next day, the two women confronted Denys with the truth about their relationship. Leaving Violet to deal with the wreckage of her marriage, Vita went off to Geneva with Harold.

The marriage between Violet and Denys continued to disintegrate as she heaped emotional abuse on the poor man, declaring that she would never care for him. He began tormenting Violet by burning her letters from Vita and checking her alibis whenever she went out. Denys was starting to show signs both of post-traumatic stress syndrome and tuberculosis. Violet didn’t want to stay with him but it would have looked bad if she had abandoned a sick husband. A compromise was reached that nothing would be done about the marriage until after her sister Sonia’s wedding. Her fiancé’s family was already against the marriage because of Mrs. Keppel’s affair with the late king. A scandal now would ruin everything.

Vita again told Violet that she would elope with her, that she would leave her old life behind. Finally the day came for the two women to leave. While Violet went ahead, Vita encountered Denys, who was looking for Violet, while she was waiting for the boat to France at Dover. The two struck up an unlikely friendship, which strengthened on the boat. In Calais, Violet refused to return with Denys. Harold Nicolson caught up with them in Amiens to complete the unhappy foursome. Accusations were flung, including that Violet was unfaithful to Vita with Denys, which Violet denied. The whole thing was too much for the two women. Finding that they were trapped on either side, Vita folded up her tent and returned with her husband to London. Although the affair continued intermittently for a year, the handwriting was on the wall. While Vita was everything to Violet, Vita had a life independent of her, with Harold, their sons, her gardening for which she would also become famous, and her writing. Violet felt she had been beaten by the bounds of convention.

Denys threatened not only to sue for divorce but to bring Vita’s name into it, and Mrs. Keppel said no way. Violet was not going to disgrace the family any more than she already had. More to the point, if there were a divorce, she would have nothing to do with Violet emotionally or financially. Violet, who adored her mother, could not live without her approval. She had learned a hard truth, that society would never condone the love that she shared with Vita; it led to social ostracism and self-loathing.

Violet thought she was a rebel, that by openly flaunting convention, she would show the world that there was more to love than people dreamed of. She gave no thought at all to the pain she caused her parents, her sister, or particularly Denys. She never once realized how much she had wronged him or hurt him or even apologized for what she did to him. In her romantic fantasy, love should have conquered all. But there was the reality of life. As much as she deplored the hypocrisy of her mother’s life and her aristocratic set, she also longed to emulate her mother and please her.

She and Denys settled in France, to avoid further scandal, where they led separate lives until his death in 1929. Chastened, Violet modified her behavior, but not her sexuality, learning the value of discretion to become more socially acceptable. She became involved with the American-born Princess de Polignac, who preferred to keep her private life private. The relationship relieved the boredom and loneliness Violet had felt since the end of her relationship with Vita. But she was never again to give herself so completely. Relationships would always be tempered with reservations.

She wrote novels, including her own account of her affair with Vita disguised as a heterosexual relationship; threw dinner parties; told witty stories; and hobnobbed with members of Parisian literary society. Colette nicknamed her “Geranium.” Violet became a notable eccentric who embellished stories; but she was still in thrall to her mother, who, she wrote, still treated her like a little girl. When she and Vita reconnected in England during World War II, neither one wanted to stir the embers of the still burning fire. After the war, Violet resumed her life in France but her mother’s death in 1947 was a great blow. She wrote, “What has happened to me since is but a post scriptum. It really doesn’t count.”

Increasingly fragile as she got older, Violet passed away in 1972, ten years after Vita, at L’Ombrellino, a villa overlooking Florence that she had inherited from her parents. Her ashes are buried with her mother’s in Florence.

Zelda Fitzgerald

1900-1948

Both of us are very splashy vivid pictures, those kind with the details left out, but I know our colors will blend, and I think we’ll look swell hanging beside each other in the gallery of life.

—ZELDA FITZGERALD TO SCOTT, TWO MONTHS BEFORE THEIR WEDDING

On a hot summer night in July 1918 at the Montgomery Country Club, Zelda Sayre sauntered out onto the dance floor and captured the heart of First Lieutenant Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald. She was a few days short of turning eighteen, but already a celebrity by Montgomery standards. Zelda had a reputation as something of a wild child. Flirtatious and flamboyant, she enjoyed scandalizing her proper Victorian father, Judge Anthony Sayre, who was one of the leading citizens of the capital.

There were Southern belles and then there was Zelda Sayre. Tall and slender, with honey blond hair and a Kewpie doll pout, Zelda had teenage boys and college students tripping over themselves to get to her. She had so many beaus that she was attending parties every single night of the week. When her father forbade her from going out so much, Zelda just climbed out the window and shimmied to the ground. Zelda was vivacious and fearless, and she genuinely didn’t care what people thought of her. Whether wearing a form-fitting swimsuit that appeared almost nude or roller-skating down the steepest hill in town, Zelda was noticed. She wore makeup and bobbed her hair, drank “dopes” (Cokes with aspirin) at the drugstore, and parked with boys on Boodle’s Lane. But she knew just how far to go in her behavior without ending up with a reputation for being “fast.”

Not yet twenty-two when they met in the summer of 1918, Fitzgerald was on the five-year plan at Princeton University and hadn’t graduated. In his Brooks Brothers uniform, his handsomeness almost made him look feminine. “He smelled like new goods. Being close to him, my face in the space between his ear and his stiff army collar was like being initiated into the subterranean reserves of a fine fabric store,” Zelda later wrote.

Soon he was joining the throngs of men who hung about at the Sayre house on Pleasant Avenue, vying for Zelda’s attention. In a matter of a few weeks, the two were in love. They courted, sitting on her front porch sipping lemonade and dancing all night at the country club. As a gesture of his affection, he carved their initials into a tree. They slept together almost immediately, leaving Scott wondering who else might have been to paradise with her before him. For two years he and Zelda carried on a long-distance relationship. Scott was tormented by Zelda’s letters, which included details of all the parties and dances she was going to while he was gone.

Zelda still continued to see other men; she was young, why shouldn’t she have fun? After all, Scott was all the way up in New York City. He certainly couldn’t expect her to sit home playing tiddlywinks, could he? The biggest obstacle to their getting married was Fitzgerald’s lack of money. Zelda had been raised to be a rich man’s wife. Quitting his advertising job, he holed up back in St. Paul, Minnesota, subsisting on Coke and cigarettes, to rewrite his first novel, published in 1920 as This Side of Paradise. The heroine in the book owed much to Zelda. He even used portions of her diary and her letters to create the character of Rosalind Connage.

Now that he was about to be a published author, Scott took the train down to Montgomery to propose to Zelda. Fitzgerald’s friends warned him not to marry “a wild, pleasure loving girl like Zelda.” While he conceded that he might be in over his head, he explained, “I love her and that’s the beginning and the end of it.” As for Zelda, now almost twenty years old, she was ready for a new adventure. Scott wove tales of what their life would be like in New York. After four years of being the most popular belle in Montgomery, perhaps Zelda sensed that her time was coming to an end. There were younger and prettier girls just waiting in the wings to take her place.

The first years of their marriage were spectacular. Scott and Zelda were the celebrity couple of the Jazz Age. Stories abounded of their antics: Zelda and Scott riding on top of a taxicab, Zelda jumping full-clothed into the fountain in Union Square, the pair spending a half hour going through the revolving door at the Commodore Hotel. Everything they did was news. They were good-looking and risqué. Soon they were hobnobbing with the glitterati of Manhattan’s café society as well as its literary lights. They met everyone from Dorothy Parker to Sinclair Lewis. Silent screen star Lillian Gish said of them, “The Fitzgeralds didn’t make the twenties, they were the twenties.” They seemed to symbolize a generation that had been baptized by fire in the Great War. Their lives were filled with an aura of excitement, bathtub gin, and romance.

Fueled by bootleg liquor, they spent several weeks drinking, attending the theater or rooftop parties, and going through Scott’s book royalties faster than they came in. They lived in hotels for the most part, since Zelda was crap at housekeeping, throwing lavish parties in their suite. Soon they were doing outlandish things just for the effect; they were the Spencer Pratt and Heidi Montag of the Jazz Age but with charisma and talent. Scott quickly shed his Midwestern morals, performing a striptease along with the talent onstage one night, which got him and Zelda evicted from the theater. Zelda had no qualms about taking off her clothes and having a bath in other people’s homes.

Because of her status as Mrs. F. Scott Fitzgerald, people were clamoring for her views on the “New Woman,” as well as the phenomenon known as “the flapper,” a young woman free from the conventions of the day, smoking, drinking, and doing what she pleased. Zelda was the flappers’ patron saint. She turned out to be a natural as a writer with a distinctive voice. Scott had no qualms about having Zelda’s stories published either under their joint names or under his name alone. There was a practical reason for this. Stories under his name paid top dollar, as much as four thousand dollars at the height of his popularity, while stories with Zelda’s name alone rarely fetched as much.

Zelda at first had no objection to Scott not only publishing her work under his name but also advancing the idea that she was his Muse. In fact, they both encouraged the idea. The cover of The Beautiful and Damned featured a couple that looked amazingly like Scott and Zelda. She wrote a tongue-in-cheek review of the book for the New York Tribune entitled “Friend Husband’s Latest,” in which she said that Fitzgerald “seems to believe that plagiarism begins at home.” From the beginning Zelda considered herself Scott’s literary partner. She read his drafts and discussed story ideas, and soon she was line editing and creating dialogue.

But as the years passed, Zelda became less sanguine about the situation. The cracks began to show beneath the façade of the Jazz Age flapper and her consort. While they were courting, Zelda had held all the power, with her elusiveness and her ability to torment him with her other flirtations. The only way that Scott could hold Zelda was to marry her. Once they were married, however, the balance of power shifted in Scott’s favor. Zelda became dependent on him, and not just financially—her notoriety derived in part from being his wife. Even her small forays into writing were supported solely due to her marriage to Scott. For his part, Scott was surprised when people he admired, like the critic George Jean Nathan, were interested in Zelda, as an individual apart from her connection to him.

And then there was the drinking. At Princeton, Scott had had a reputation for being a hard drinker. Initially, he would stop drinking while he wrote, but as the years passed and it took longer and longer to write his novels, he began to drink in order to write. Zelda could knock back a few cocktails as well as Scott, but there was a darker side to Scott’s drinking. He could be verbally abusive and belligerent while drunk.

They lived an increasingly nomadic existence, as they crisscrossed the country from Connecticut to St. Paul and Montgomery, finally settling in Great Neck for two years while they tried to economize and Fitzgerald wrote. When Scott wrote, he required a life free from distractions, which left Zelda at loose ends. While he holed up in his study working feverishly on the short stories that kept them afloat between novels, she spent her days swimming, playing tennis, or waiting for the bootlegger to show up with their booze. Even the birth of their daughter, Scottie, didn’t completely fill up her days.

Attempting to save money, the Fitzgeralds sailed for Europe, where the dollar was strong and drinking was legal, along with fifty-five pieces of luggage, and settled in the south of France. They would spend the better part of the next five years abroad. While Scott hunkered down to finish what would be his masterpiece, The Great Gatsby, Zelda was bored. She and Scott became friendly with a group of French pilots stationed nearby. For Zelda, it brought back memories of her glory days in Montgomery when pilots from the nearby airfield would fly over her house. Zelda became particularly friendly with one in particular. When she told Scott that she had fallen in love and wanted a divorce, he locked her in the villa. Depressed, Zelda took an overdose of sleeping pills. Still only twenty-four, she felt as if life was passing her by. Her unhappiness manifested itself in illness; she began to suffer from anxiety attacks and colitis.

They continued to quarrel and make up incessantly, seeming to egg each other on to see who could be the more outrageous. Once Zelda threw herself under the wheel of their car and goaded him into driving over her, which he almost did. They fought over his drinking, which was getting in the way of his work. When Scott flirted with an aging Isadora Duncan in a café in the south of France, Zelda threw herself down a flight of stone stairs.

Needing a creative outlet of her own, Zelda was drawn back to her first love, ballet. Despite the fact that ten years had passed since her last dance class, Zelda became fanatical about practicing. She installed a mirror and a barre so she could work sometimes for eight hours a day. As Scott was stalled in writing his new novel, he resented Zelda’s determination to revive her dance career. He was unwilling to admit that she might have real talent, that she needed to be seen as more than his wife. Despite her age, Zelda was offered a position with a company in Naples, dancing a solo in Aida. No one knows exactly why she turned it down. Perhaps just the offer was enough for her.

In 1930, Zelda had her first breakdown. The sparkle had gone out of her; she seemed tired and distracted. Her blond hair turned dark brown, and she lost weight. She complained of hearing voices in her head, and her speech became confused. Diagnosed with schizophrenia, for the rest of her life she would be in and out of institutions, most of the time voluntarily. Scott blamed her breakdown on her obsession with dancing. She agreed to cease dancing if he would stop drinking but he refused to see he had a problem.

While recuperating at the Phipps Clinic at Johns Hopkins in 1932, Zelda began secretly working on her first novel, Save the Waltz. It was the semiautobiographical story of a young woman from the South who marries a famous artist. Without telling Scott, she sent the manuscript to his editor, Maxwell Perkins, at Scribner. When Scott finally read the manuscript he felt betrayed; as Zelda’s biographer Nancy Milford writes, he believed that Zelda had directly invaded what he considered his domain. How dare Zelda use her own life for her work? Her life belonged to Scott, not to her. It was as if she were his personal property, not just his wife. He was writing his own book, one that would become Tender Is the Night, which used some of the same material.

During a joint session with her doctor, the transcript running 116 pages, Scott blamed her for the fact that he hadn’t published a novel in seven years, refusing to see the role that alcohol played in his inability to work. He disparaged her, calling her a third-rate writer and a third-rate ballet dancer. Zelda wearily responded that he was making quite a violent attack on someone he considered third-rate. She assured him that she was not trying to be “a great artist or a great anything.” She just needed a creative outlet, to have a sense of self. Nevertheless she changed the novel according to his wishes and it was published in October of 1932. The reviews were poor and it sold less than half of its three-thousand-copy print run. Zelda earned $120.73 from her novel.

Although they never lived together as husband and wife again, Scott never abandoned his wife during her years of mental illness. In 1936, Zelda entered the Highland Hospital in Asheville, North Carolina, where she would spend the next twelve years on and off. Scott died in Hollywood in 1940, having last seen Zelda a year and a half earlier. She was too unwell to attend his funeral. Fitzgerald left her an annuity to help pay for her medical bills. When she was well, she lived with her mother in Montgomery until her demons came back, and she would go back to the hospital. She submitted to electroshock therapy, which helped but also damaged her memory.

Zelda spent her remaining years working on a second novel, which she never completed, and she painted extensively. In 1948, a fire broke out on the top floor of the hospital, causing her death. It took some time before her charred body could be identified. Scott and Zelda are buried with the other Fitzgeralds at Saint Mary’s Catholic Cemetery. Inscribed on their joint tombstone is the final sentence of The Great Gatsby: “So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”