FOUR

Crusading Ladies

Anne Hutchinson

1591-1643

A woman of a haughty fierce carriage, a nimble wit and an active spirit, and has a very voluble tongue, more bold than a man.

—JOHN WINTHROP ON ANNE HUTCHINSON

On a chilly November day in 1637, the meetinghouse in Cambridge, Massachusetts, was packed as Anne Hutchinson, declared Public Enemy No. 1 by the founders of the colony, was led into the dimly lit room to stand trial. At the time, Anne was forty-six, the mother of twelve living children, a grandmother, and pregnant with her fifteenth child. She was well known in the community, as a midwife and nurse.

In the three years since her arrival in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Anne had managed to piss off a lot of powerful people, specifically the clergy. Her “crime” was holding weekly meetings at her home to discuss scriptures and theology. At first her meetings were only attended by women, who couldn’t wait to hear her unique take on the latest Sunday sermon. Ironically Anne had been chastised for not joining in at these meetings when she first arrived in the colony.

9 To the women, Anne was like Oprah and Billy Graham wrapped up in one package. She was witty and genuinely wanted to help other women, whether by medical care or by spiritual counseling. Her gift to them was her surety about her faith and salvation.

The women soon convinced their husbands to attend her meetings. The meetings became so popular that she had to add an additional day to accommodate the demand, and they began attracting powerful men, such as Sir Harry Vane, soon to be governor. Vane was the son of one of Charles I’s Privy Council, sent to the colony for “seasoning.”

10 Her stand against the war with the Pequot Indians influenced her male followers not to fight.

Anne’s chief nemesis was the most powerful man in the colony, five times governor John Winthrop. He described her in his journal as “a woman of a haughty fierce carriage, a nimble wit and an active spirit and has a very voluble tongue, more bold than a man.” And those were the nice things. He also called her “an instrument of Satan,” “enemy of the chosen people,” and “this American Jezebel.” John Winthrop had been keeping an eye on her both figuratively and spiritually since the Hutchinson family got off the boat in 1634. He conveniently lived across the street from them in Boston, where he had a bird’s-eye view of the comings and goings at the Hutchinson house. Winthrop began making a long laundry list of what he considered to be her “errors.” It eventually came to one hundred items.

It was a crucial moment in the fledgling colony. Having fled England to escape religious intolerance, the Puritans then proceeded to impose religious uniformity on others. Like Abraham Lincoln 230 years later, Winthrop believed that a house divided against itself could not stand. Dissension had to be stopped before it destroyed Winthrop’s “holy city on the hill.” Roger Williams

11 and Anne’s own brother-in-law John Wheelwright had already been exiled for their unorthodox beliefs. The bickering got so bad that Harry Vane resigned as governor of the colony (which opened the door for Winthrop’s return to power), claiming he had to return to England for “personal reasons.” The division also came down along class lines. Winthrop’s supporters were those who had been landed gentry in England and conservative. Anne’s supporters were the merchants and other professionals, the rising middle class.

Anne came by her opinionated nature honestly. Her father, Francis Marbury, spent the first three years of her life under house arrest by the church on a charge of heresy,

12 the same charge that would be brought against Anne. A Cambridge-educated clergyman, he was jailed only a few months into his first post. Marbury had repeatedly challenged the Anglican Church authorities on religious truth. Although Anne wasn’t formally educated, her father taught her and her siblings, using his trial transcriptions, the Bible, and a book of martyrs. Arguing about scripture passed for leisure time in the Marbury household.

The colony magistrates passed a series of resolutions that were aimed at curbing dissidence, including a direct condemnation of meetings with more than sixty people. Anne had more than that on a slow day. They were also annoyed that when she began questioning whether certain ministers had the “seal of the spirit,” her followers began to heckle some of these ministers at their sermons. This was considered “traducing the ministers and the ministry” and it was a big no-no.

Anne was summoned before the General Court with Winthrop presiding. He told her that she was “called as one of those that have troubled the peace of the commonwealth.” Anne refused to meekly submit, pointing out that she hadn’t actually been charged with anything. Despite her advanced pregnancy, she was forced to stand for several days as they tried desperately to get her to admit to blasphemy. Not exactly Christian behavior! She and Winthrop sparred back and forth like prizefighters, Anne bobbing and weaving as she matched him scripture for scripture. Winthrop accused her of breaking the fifth commandment of honoring thy father and mother, which to Winthrop included all authority figures, including him. When she was told this, Anne replied, “Put the case, sir, that I do fear the Lord and my parents. May not I entertain them that fear the Lord, because my parents will not give me leave?”

When Winthrop tried to prove that her meetings were public rather than private, Anne insisted that since women had no public role, her thoughts were private and not subject to censure. If she decided to have some friends over to her house for some cider and a little religious talk, that was her business, no one else’s. Anne even cited the apostle Paul’s letter to Titus, which called for “the elder women to instruct the younger.” Winthrop then accused her of keeping the women from getting their husbands’ dinner on time. Time and again, Anne had Winthrop against the ropes, sweating, until Winthrop finally snapped, “We do not mean to discourse with those of your sex.” Kind of hard not to do when the person on trial is a woman.

But it wasn’t just the meetings that riled them up. It was Anne’s unique take on scripture that disturbed the Puritan leaders. Like the Puritans, Anne believed in God’s free grace, which was a covenant between God and man, where God drew the soul to salvation. Where Anne and the Puritans were at loggerheads was on the need to prepare oneself by doing good deeds. Anne thought that this smacked of buying your way into heaven.

She was ahead of her time in her belief that everyone could be saved, even nonbelievers. This didn’t sit well with the Puritans, who believed that they were God’s chosen people. And then there was the matter of her belief that God placed the Holy Spirit direction within those he saved, and guided their actions like some sort of cosmic GPS. She was also a bit picky about which ministers she felt had a direct line to God. Only her brother-in-law and the Reverend John Cotton, who had also left England not long before, having upset the church authorities, met her high standards. And then there was her belief that one could have a personal relationship with God cutting out the middle man of clerical authority. This threatened the very foundation on which the Puritans had built their state, their church, and their lives. They even came up with a special name for her beliefs called Antinomianism, which is Latin for “against the law.” Winthrop and his buddies of course were on the right side of the law.

When Anne’s spiritual guru and best friend, John Cotton, was called as a witness for her defense, things got really interesting. Cotton was caught between a rock (Anne Hutchinson) and a hard place (John Winthrop). He considered Anne to be his spiritual collaborator, writing that she was “the apple of our eye.” But the pupil had surpassed the master. And he’d already gotten into a heap of trouble back in the old country for his beliefs, so he was walking a fine line. Cotton managed to defend Anne, sort of. He wouldn’t admit that Anne had talked trash about the other ministers in his favor, although he made certain to point out that he was distressed at the idea. With Cotton’s testimony, Anne would have defeated the charges against her.

But Anne couldn’t keep her mouth shut. Having an audience was just too good to resist. She was like the smartest girl in class who can’t help showing off how smart she is. Winthrop, being the gentleman that he was, let her hang herself. He must have been rubbing his hands with glee, though. Anne started off talking about her journey of faith, how she remained unsettled by the quality of the preaching in the Church of England.

That would have been fine if she had just stuck to that topic, but then she dug a hole for herself that was deeper. She continued on about how the spirit of the Lord opened the Bible and thrust certain passages in her mind. She then revealed that “the Lord did give me to see that those who did not teach the New Covenant had the spirit of the Antichrist.”

Oh, no, she didn’t! The judges were flabbergasted. It was one thing for a man to consider revelation through scripture, but the idea that a woman should claim such a thing was crazy talk. However, Anne was not done. Not only did she claim to hear the voices of Moses, God, and John the Baptist but she then pulled out the big guns. Comparing herself to Daniel in the lion’s den, she told them that she knew she was going to be persecuted in New England and that their lies would bring a “curse on upon you and your posterity and this whole state.” Yeah, nothing like telling the people who hold the power of life and death over you that they are going to be cursed for punishing you. With these revelations, even Cotton had to back off.

The judges ruled that Anne would be jailed under house arrest until the spring, when she would be dealt with by the church. They weren’t so kind to her supporters, who were disenfranchised for signing a petition in support of her. The others were disarmed just in case they decided they had a divine revelation to kill the judges. Many of the petitioners recanted and were allowed to keep their guns.

Anne’s actions had the Puritan godfathers running so scared that, to minimize Hutchinson’s threat, they decided to get started on building the college they’d been planning. After her trial, they finally got cracking on it. Harvard graduates everywhere can thank Anne Hutchinson for the fact that their school was founded to stop smart-alecky female fanatics from getting the better of the law in court and convincing other females that they had a right to their own opinions. Modeled after Winthrop’s alma mater, Cambridge, the new college was named after John Harvard, a recent immigrant to the colony, who had bequeathed half his estate and his library to the college before his premature death at the age of thirty.

In March 1638, Anne was accused of heresy and also of “lewd and lascivious conduct” for having men and women in her house at the same time during her meetings like they were having a spiritual orgy. She was found guilty and excommunicated by the Boston church. It had the opposite effect on her than it would have on most people. Instead of being “oh, woe is me!” Anne was ecstatic, claiming that “it was the greatest happiness, next to Christ that had befallen her.” Winthrop claimed that actually it was the churches in the colony that should be happy, as “the poor souls who have been seduced by her had settled again in the truth.” In other words, “Hooray for our team!”

No one knows what her husband, Will Hutchinson, thought about having to uproot his family once again. No doubt after over twenty years of marriage, he was used to his wife’s convictions. His only recorded words about Anne are, “I am more nearly tied to my wife than to the church. I do think her to be a dear saint and servant of God.” Winthrop called him “a man of a very mild temper and weak parts and wholly guided by his wife.” After leaving the colony with her family, Anne ended up on the island of Aquidneck on Narragansett Bay. Thirty families voluntarily followed her into banishment. The men signed the Portsmouth Compact, creating the new settlement of Rhode Island. Anne gave birth with great difficulty in the summer of 1638, to a hydatidiform mole, a cluster of cysts that develops in place of an embryo. The Puritan fathers patted themselves on the back and broke out the cigars when they heard the news of the “monstrous birth.” To them it just proved the point that she was evil and they were wise to kick her out.

Will Hutchinson died in 1642, having served as governor of the new colony. When it looked as if the Massachusetts Bay Colony was going to annex the Rhode Island colony, Anne decided to move with some of her children to the New Netherlands. The last thing she wanted was to be under the yoke of John Winthrop and his friends again. Anne and her family settled a farmstead on a meadow in Pelham Bay, near what is now the Split Rock golf course in the Bronx.

A year later, Siwanoy Indians scalped Anne and six of her children and burned down their house. Only her daughter Susan survived. Anne had been warned about a possible Indian attack, but she ignored it because of her long history of good relations with the Natives. Instead of arming herself, or abandoning her home, Anne did what she had always done: put her faith in the will of God. The Siwanoy chief Wampage renamed himself Ann-Hoeck after his most famous victim. Nine-year-old Susan was adopted by the Siwanoy and lived with them until she was eighteen, when she returned reluctantly to her family in Boston. The river near where Anne was killed is now known as the Hutchinson River.

Anne Hutchinson was an American visionary, a pioneer who became the poster girl for religious freedom and tolerance. Long before the Constitution guaranteed the right of free speech, Anne was defending hers. In 1987, Governor Michael Dukakis pardoned Anne, 350 years after John Winthrop “banished [her] from out of our jurisdiction as being a woman not fit for our society.” A bronze statue of Anne stands proudly on the front lawn of the Massachusetts State House, calling her a “courageous exponent of civil liberty and religious toleration.” Ironically, her statue looks toward the cemetery, steps away from where her old nemesis John Winthrop now rests.

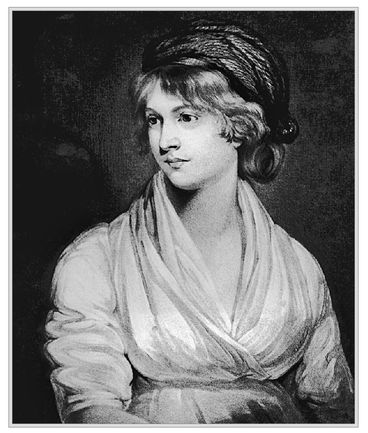

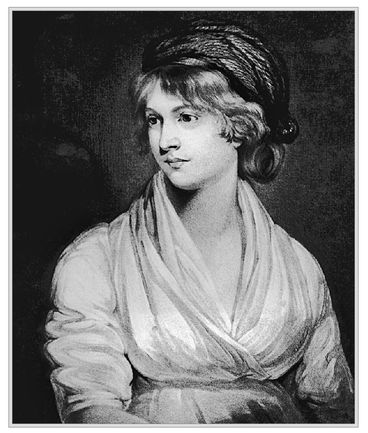

Mary Wollstonecraft

1759-1797

I am going to be the first of a new genus, the peculiar bent of my nature pushes me on.

—MARY WOLLSTONECRAFT

Mary Wollstonecraft wrote her masterwork, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, in a frenzy in six weeks, distilling thirty years of anger. Published in 1792, it was an immediate success, attracting admirers that included future First Lady Abigail Adams. It was a ferocious rejection of the traditional ideas of femininity. She was not writing to please; she wrote about what she felt was real. In this landmark work she argued that women were not naturally inferior to men, but appeared to be only because they lacked an education. She suggested that both men and women should be treated as rational beings and imagined a social order founded on reason.

From the moment of her birth in 1759, Mary had a chip on her shoulder. She felt unloved and unappreciated by her parents, who preferred her older brother, Ned, to her. And as each new baby was born in the family, Mary got lost in the shuffle. When her paternal grandfather died, his will divided his estate between her father, her brother, and her aunt. Nothing was left to her and her sisters, a slight that she never forgot. It was her first hint of the injustices that were meted out to women.

With his inherited money, Mary’s father decided to pursue the life of a country squire, moving the family out of London to near Epping Forest in Essex. While he was good at spending, he had no skill at farming. As the years passed, the family slowly slid down the social ladder. They moved from Epping to Yorkshire and then back to London again. Her father began to drink heavily as his fortunes dwindled. His only talent was for beating his wife. Mary tried as much as possible to protect her mother, sometimes even sleeping outside their room. Despite her intervention, Mary was not loved for it. From that point on, Mary began to despise her father and pity her mother.

Even as a young girl, Mary wore her heart on her sleeve. She was a woman of tempestuous emotions, given to self-pity and depression, huge resentments, and a habit of impulsive and sometimes imprudent attachments. “I will have the first place in your heart or none,” she told a female friend at the age of fourteen. She suffered from what they called “an excess of sensibility”; in other words, she was a bit intense. Although it was the fashion to conceal emotion, Mary rejected that notion completely. She never hid behind a mask of polite indifference or protected herself from getting hurt. She threw herself wholeheartedly into her friendships and love affairs and couldn’t understand when the feelings were not returned with equal fervor.

She had decided against marriage at the age of fifteen, seeing how trapped her mother was, and she had no dowry even if she had been so inclined. Nothing she had seen of men had endeared them to her. Not her brother, Ned; her father; or her brother-in-law Meredith Bishop. But she also doubted her ability to attract a husband. Handsome rather than beautiful, Mary cared nothing for fashion, and while she was tall, with lovely fair hair and hazel eyes, she also had a sharp tongue. Mary’s own courage and determination often made her impatient and short with those who lacked her drive and energy.

Mary’s feelings about marriage seemed to be confirmed when she was summoned by her brother-in-law to help her younger sister, Eliza, after she gave birth. Eliza, who was probably suffering from a bad case of postpartum depression, convinced Mary—or was it the other way around?—that her only chance to get better was to leave her husband. Worried for her sister’s sanity, and appalled by her brother-in-law’s unsympathetic attitude, Mary decided to rescue her, making all of the arrangements for them to flee. When Eliza, missing her child, began to waver, Mary made her stand firm. Her actions not only deprived Eliza of her child, who died before she was a year old, but with no support from her husband, she now had no choice but to work for a living, leaving her resentful and bitter of Mary’s later success.

In order to make a living, Mary, her sisters, and her best friend Fanny Blood set up a school together in Newington Green. Despite her lack of formal education, Mary had developed radical ideas about teaching. She believed that children shouldn’t learn by rote or be disciplined by the rod. The residents of the town were Dissenters,

13 Jews, and others who had supported the Americans in the recent Revolutionary War, including the Reverend Richard Price. Although not a Unitarian, Mary went to hear his sermons, finding that his ideals appealed to her. This was the beginning of her political education. Mary found the Dissenters that she met hardworking, humane, critical but not cynical, and respectful toward women; they proved kinder than her own family.

Initially a success, the school failed after Mary left to go to Lisbon in 1785 to nurse Fanny, who had married and was expecting her first child, but she didn’t survive. Depressed and distraught over her friend’s death in childbirth and the closure of the school, Mary took a job in Ireland working for the Viscount Kingsborough and his wife and their brood of children. Her inability to hide her emotions would get her into trouble during the year that she worked for the Kingsborough family as a governess. She found it hard to hide her contempt for the useless lives of the aristocracy, and the family alternated between treating her like an equal or like a servant, depending on their whims. She ended up in a power struggle with Caroline, Lady Kingsborough, over the affections of her daughters and she made the mistake of starting a flirtation with George Ogle, whom Caroline had marked out for her own. While traveling in England, Mary was fired by Lady Kingsborough.

With no money and no references, Mary had few options. She was saved by Joseph Johnson, a publisher she had become acquainted with when she lived in Newington Green. He had agreed to put out her first book, Thoughts on the Education of Daughters , for ten guineas before she left for Ireland. Now she made the impetuous move to make her living solely by her pen. This was a radical and daring choice since few women, or men, for that matter, could support themselves solely by writing.

Johnson put her up in a house and hired her to edit and write reviews for several of his publications, primarily the Analytical Review. He became much more than a friend; Mary described him in her letters as a father and a brother. He also agreed to publish her novel, entitled simply Mary: A Fiction, encompassing her experiences in a thinly fictionalized version of her life, and set her up in rented lodgings. She taught herself French and German and translated texts. Johnson asked her to attempt Italian but it gave her a headache. Mary soon began writing a monthly column in which she criticized, with humor and disdain, novels that she felt had weak female characters. She tartly dismissed one work, calling it “Much ado about Nothing”: “We place this work without any reservations, at the bottom of the second class.” She wrote to a friend that she was soon making almost two hundred pounds a year by her writing. She was finally able to pay her debts and to help her sisters financially.

In between all her other work, Mary found the time to write A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. In it she demanded “Justice for one half of the human race.” Mary did no special research for the book. She didn’t need to; she lived it. Mary had experienced firsthand the plight of poor, respectable women who were forced to earn a living. She advocated training single women for adequate employment and was the first to call marriage “legal prostitution.” Mary deplored the relegation of women to a state of ignorance and dependence. She was the first to propose that women were taught to be superficial and simpering; they weren’t born that way. In her book, she wrote that men and women were human beings before sexual beings, that psychologically they were both the same. She courted controversy by encouraging parents to teach their children about sex and promoted the idea of coeducational schools.

The book was published in England, America, Germany, and France and made Mary famous. Although it only sold three thousand copies in its first five years, it was the first treatise of its kind published in Britain and America to enter the mainstream. Aaron Burr used the book as a guide to teaching his daughter Theodosia. Amid the hosannas were a few sour notes. There was a cry to burn Mary in effigy. Horace Walpole famously called Mary “a hyena in petticoats.”

Mary left for Paris in December 1792, joining a circle of expatriates then in the city. In the stimulating intellectual atmosphere of the French Revolution she met and fell passionately in love with Gilbert Imlay, an American writer and adventurer. While Mary had taken a prim attitude toward sex in her book, Imlay awakened her passions. He was thirty-nine, handsome, charming, and easygoing. He told Mary that he considered marriage a corrupt institution, which she wasn’t savvy enough to know meant he was keeping his options open. Like a lot of women, Mary built up an image in her head of Imlay that had nothing to do with reality. Imlay, on his part, must have been flattered to have this famous woman so into him, but he had no idea what he was letting himself in for. As Virginia Woolf wrote, “Tickling minnows, he had hooked a dolphin.”

As the political situation grew worse, Imlay registered Mary as his wife in 1793, giving her the protection of his American citizenship, even though they were not married. To Mary this was proof of his commitment to her. “My friend,” she told Imlay, “I feel my fate united to yours by the most sacred principles of my soul.” She soon became pregnant, and while waiting to give birth at Le Havre, Mary spent her time writing An Historical and Moral View of the French Revolution, which was published in December 1794. On May 14, 1794, attended by a midwife, she gave birth without complications to her first child, Fanny, naming her after her late friend.

Mary reveled in motherhood, and the pleasures of breastfeeding. She wrote to her friend Ruth Barlow, “My little Girl begins to suck so MANFULLY that her father reckons saucily on her writing the second part of the Rights of Woman.” Refusing to let Fanny be swaddled, she dressed her in loose, light clothing, allowing her plenty of fresh air, which scandalized the women of Le Havre who called her the “raven mother,” considering her unfit to be a mother.

Imlay became tired of the maternal Mary and eventually left her. She attempted suicide twice, first by an overdose of laudanum, the second time by trying to drown herself in the Thames. Mary considered her suicide attempts completely rational, writing after her second attempt, “I have only to lament, that, when the bitterness of death was past, I was inhumanly brought back to life and misery.” In a last-ditch attempt to win Imlay back, she agreed to help him recover cargo stolen by a Norwegian captain. With only her infant daughter and a teenage nursemaid as her companions, Mary spent four months battling seasickness, traipsing over fjords, and haggling with officials all to save her lover’s bacon to no avail. Her reward was to discover on her return that Imlay had taken up with another woman. She did get a bestseller out of the deal, publishing her account of her travels as Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark in 1796. William Godwin later wrote these prophetic words in his memoir of Mary’s life: “If ever there was a book calculated to make a man in love with its author, this appears to me to be the book.”

Calling herself Mrs. Imlay in order to bestow legitimacy to Fanny, she returned to London. In April 1796, Mary presented herself at Godwin’s lodgings. The first time they had met, they disliked each other. Godwin had come to Joseph Johnson’s house to hear Thomas Paine, but, to his annoyance, Mary wouldn’t shut up. They had become reacquainted in January, before her second suicide attempt. Just friends at first, they soon became lovers. It was a tempestuous relationship. Mary was still gun-shy after Imlay, and Godwin, at forty, had gotten used to the life of a bachelor. By December, however, she was pregnant. They married in March 1797. Mary wasn’t about to have another illegitimate child, and after some reluctance, Godwin agreed.

Despite their marriage, they both still prized their independence. “I wish you for my soul, to be riveted in my heart, but I do not desire to have you always at my elbow,” she told Godwin. So Godwin rented separate quarters to work. They communicated by letter, several times a day, and each spent evenings, as before, with separate friends. However, their happiness was short-lived. On August 30, Mary went into labor. Infection set in, and nine days after giving birth to a daughter, named Mary, Wollstonecraft expired.

Godwin was devastated; he wrote to his friend Thomas Holcroft, “I firmly believe there does not exist her equal in the world. I know from experience we were formed to make each other happy. I have not the least expectation that I can now ever know happiness again.” In January 1798, Godwin published his Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. In his grief, Godwin wrote a warts-and-all memoir that did a great deal of damage to Mary’s reputation. Godwin turned Mary into a tragic heroine, and readers were appalled that he would reveal intimate details about her love affairs and suicide attempts. The book also portrayed Mary as a woman deeply invested in feeling, who was balanced by his reason and as more of a religious skeptic than she actually was. Mary’s reputation wasn’t restored until one hundred years after her death when Millicent Garrett Fawcett, a suffragist, wrote an introduction to the centenary edition of Vindication . In the two-hundred-plus years since her death, Mary has become one of the most discussed, admired, demonized, reviled, and criticized feminists in history. Her life was full of contradictions that confound modern feminists—she shunned marriage, yet married; she admired the ideas of the French Revolution, but hated the bloodshed. However, her unconventional ideas lived on in her daughter Mary Shelley.

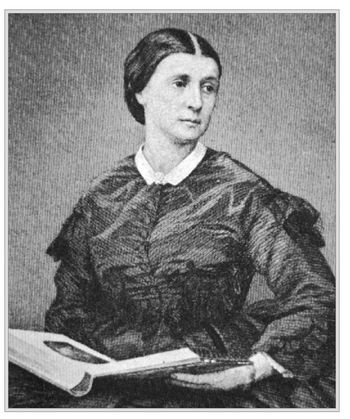

Rose O’Neal Greenhow

1813?-1864

I am a Southern woman, born with revolutionary blood in my veins.

—ROSE O’NEAL GREENHOW

In July 1861 at the height of the Civil War, a young woman managed to deliver vital information about Union troop movements to General Pierre Beauregard of the Confederate army, stationed near a little town called Manassas in Virginia. She kept the small piece of paper, containing a combination of numbers written in ink, hidden in a black silk bag no bigger than a silver dollar tucked in the heavy coil of her dark hair. Where had she gotten the information from? Rose O’Neal Greenhow, a Washington matron, Southern sympathizer, and Confederate spy. When Rose heard of the subsequent Confederate victory at the First Battle of Bull Run, she always believed that it was her information that made the difference.

Born Rose O’Neale, her family lived on a small plantation in Montgomery County,

14 Maryland. The middle child of five daughters, she was high-spirited, with dark eyes and a will of iron. When Rose was four years old, her father was found dead by the side of the road, after spending the afternoon and night drinking in a tavern. His favorite slave, Jacob, was tried and convicted for killing his master in a drunken rage. Rose’s mother was given four hundred dollars’ compensation for losing her slave to the gallows.

Her mother tried to keep the family together and to save the farm, but after a few years, everything was auctioned off to pay the remaining debts. Rose and her sister Ellen were sent to live with an aunt and uncle who ran a boardinghouse in Washington, DC, that served as a temporary home to lawmakers while Congress was in session. The young women were introduced into Washington society through the connections they made while living at the boardinghouse. Rose’s wit was sharp, her manner dynamic, and the politicians were soon calling her “Wild Rose.”

Their days were filled making social calls or spending time in the visitors’ gallery watching the debates on the Senate floor, which was a popular pastime. These were the days when great orators such as Daniel Webster, Henry Clay, and John C. Calhoun took the floor. Women swooned over their favorite orators. Rose became particularly fond of Calhoun, who became a father figure to her, and she often sought his advice. He and Rose became very close; her thoughts about slavery and the South were formed by the time she spent with him. She once wrote about him, “My first crude ideas on State and Federal matters received consistency and shape from the best and wisest man of this century.” Rose’s sisters made socially advantageous marriages, which helped bring her more into society. The next step for Rose was to also make a good marriage.

Robert Greenhow was one of the most eligible bachelors in the capital. From a fine Virginia family, Greenhow was cultured; he’d lived abroad, spoke several languages, and was working for the State Department as a translator and librarian. They were married in 1835. Rose was gregarious and social, while Robert was more comfortable with his books and maps, but they shared an interest in learning. Rose was passionate about preserving the Southern way of life, including slavery. She adamantly opposed the abolitionist movement, believing that blacks were inferior to whites. And she wasn’t hesitant to express her views.

Since Robert was not terribly ambitious, Rose was ambitious enough for the both of them. They socialized two or three times a week, and Rose learned to throw glittering dinner parties. Modeling herself after her idol, Dolley Madison, Rose became an effective and knowledgeable hostess. By the 1840s, Rose was an ardent proslavery expansionist. Over the next two decades she came to know all the movers and shakers in Washington society.

Widowed in 1854, while they were living in California, Rose received a small settlement in regard to her husband’s accidental death, but the money quickly ran out. Moving back to Washington, DC, Rose had to improvise, moving to smaller and smaller residences. The charming widow wore black clothing that she made herself, which emphasized her dramatic coloring. Easing herself back into the social whirl, she soon had several beaux who were quite smitten with her but Rose wasn’t interested in remarrying. She persuaded her old friend James Buchanan to run for president, working tirelessly for his campaign.

When Buchanan was elected, Rose once again was close to the seat of power. She was described by the New York Herald as a “bright shining light” in the social life of the new administration. Rose threw popular dinner parties, entertaining both Northerners and Southerners, but tensions ran high in the capital. At a dinner party, Charles Francis Adams’s wife expressed sympathy for the radical abolitionist John Brown. Rose snapped, “I have no sympathy for John Brown. He was a traitor and met a traitor’s doom.” These were strong words from a woman who prided herself on being the epitome of a gracious hostess. When Lincoln was elected president, the world that Rose knew came to an end.

With the Southern states seceding from the Union, Rose was eager to help any way that she could. She was recruited by Captain Thomas Jordan of the Confederacy, who taught her basic cryptography, which she diligently practiced. Although she was no longer in the inner circle, Rose still had connections in Washington, which she used to get information to send to the Confederate army stationed in Virginia under Beauregard. Using her feminine wiles, she cajoled military secrets from Union sympathizers who were so blinded by her charms, they loosened their tongues without even realizing what they were doing. Rose didn’t limit herself to powerful men but also their clerks and aides as well.

Rose, not being a trained spy, was a little careless. She kept copies of information that she had sent and didn’t completely destroy information that she had received. Her neighbors became suspicious of her and one of them reported her to Thomas Scott, who was the new assistant secretary of war. Thomas Scott hired Allan Pinkerton, founder of the Pinkerton Detective Agency, and put him on the case. Pinkerton was in Washington under an assumed name, Major E. J. Allen, working on counterintelligence as part of the fledgling U.S. Secret Service. He had set up a network of informants in the South who were sympathetic to ending the Civil War.

In August 1861, Rose was arrested on the doorstep outside her house just as she popped a note in her mouth and swallowed. The detectives put her and her youngest daughter, little Rose, under house arrest after they ransacked the house searching for evidence. Although they found a large number of documents and maps, including the ones that Rose had sewn into her dress, they missed others that she was able to destroy. A prisoner in her own home, she was watched constantly, even at night; she had to sleep with her door open. Anyone who tried to visit her was arrested. Soon other prisoners were brought to her house to join her. Rose was outraged that lower-class women “of bad character” were placed in her home.

Rose made things difficult for her guards as well as herself. She complained that her rights were being trampled on, that the food was inedible, that she had no privacy. Lincoln had suspended habeas corpus shortly after the war started. Although she was under arrest, Rose still managed to get information to her string of informants. Some of her messages didn’t go through and were added to the pile of evidence against her. Rose wrote a letter to Secretary of State William H. Seward protesting her imprisonment. “The iron heel or power may keep down, but it cannot crush out, the spirit of resistance, armed for the defense of their rights: and I tell you now, sir, that you are standing over a crater, whose smothered fires in a moment may burst forth.” A copy found its way to the Richmond Whig. The newspaper called it the “most graphic sketch yet given to the world of the cruel and dastardly tyranny” of the Yankee government. Rose’s imprisonment made her a martyr in the eyes of the South. The evil Yankees who could imprison a mother and child were grist for the propaganda mill.

After several months under house arrest, Rose and her daughter were moved to her former childhood home, her aunt’s boardinghouse, which had been turned into a Union prison. The room they were confined in would have been familiar to Rose; it was the same one where she had nursed her dying hero, Senator Calhoun in 1850, treasuring his last words. Rose complained about having to share the prison with Negro prisoners. The room was filled with vermin, so Rose would use a lit candle to burn them off the wall. She tucked clothes underneath the mattress to make it more comfortable for her little daughter. Somehow she even managed to smuggle in a pistol even though she had no ammunition.

After almost eight months in prison, Rose was finally brought up on charges of espionage. Rose was feisty and defiant to the members of the commission. Without counsel, she demanded to know what evidence they had against her, and she complained that her rights were being trampled. When they presented their evidence, including a letter Rose wrote that gave details of the Union army’s movements, Rose brazened it out, giving them no satisfaction. Although her actions were treasonable, Lincoln was reluctant to have her stand trial. Treason was a hanging offense but Lincoln had no stomach for hanging a woman. Something had to be done, though; Rose was considered too dangerous. She was given a choice: either swear allegiance to the Union or be deported to the Confederacy. Rose agreed to be deported to the South.

On May 31, 1862, after almost ten months in prison, four months on house arrest, and five months in the Capitol prison, Rose was escorted out of the city that had been her home for more than thirty years. Did she feel a pang as the wagon passed through the streets of the city where she had met her husband, given birth to her children and buried them, the avenues where she had strolled with her beaux and her sisters? Rose would never see the city again.

Before Rose was allowed to set foot on Confederate soil, she had to sign a statement as a condition of her parole that she would never set foot in the North again while the war continued. In Richmond, Rose was welcomed with open arms. She was hailed as a heroine, a true daughter of Dixie who defied the North. At a welcoming lunch, Rose cheekily raised her glass and toasted the president of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis. Davis granted her twenty-five hundred dollars for her services to the Confederacy. After her arrival, Rose was sent by Davis to Europe to drum up support for the South’s cause. Despite the fact that she suffered greatly from seasickness, Rose was eager to go.

She went to France to plead with Emperor Napoleon III and to England to do the same with Queen Victoria. Although privately people were sympathetic, Rose could not get anyone in Parliament or Napoleon III to publicly come out in support of the South or to recognize the Confederate states. In her first two months abroad, she wrote her memoir, My Imprisonment and the First Year of Abolition Rule at Washington, which sold well in Britain. She dedicated the work to “the brave soldiers who have fought and bled in this glorious struggle for freedom.” The book is a valuable record of Southern sentiment that led up to the Civil War.

Rose drowned off the coast of North Carolina on October 1, 1864, when the ship in which she was returning to America ran aground at the mouth of Cape Fear, chased by a Union gunboat. Although the captain advised that everyone stay on board, Rose was frightened of being captured by the Yankees again. She was on her way to shore when her rowboat was overturned by a large wave. Her body was found washed up onshore a few days later. She had been weighed down by gold sewn into her clothing. Searchers also found a copy of her book, Imprisonment, hidden on her person.

She was given a full military burial, wrapped in the Confederate flag, in Oakdale Cemetery, near Wilmington, North Carolina. The Wilmington Sentinel wrote that her funeral “was a solemn and imposing spectacle . . . the tide of visitors, women and children with streaming eyes, and soldiers with bent heads and hushed stares standing by, paying the last tribute of respect to their departed heroine.” Her grave bears the inscription “Mrs. Rose O’N. Greenhow. A Bearer of Dispatches to the Confederate Government.” Every year on the anniversary of her death, a ceremony is held to honor her contributions to the Confederate cause.

Rose O’Neal Greenhow was not to be admired for her views about slavery. But her devotion to the Confederacy and her ability to further her cause through her charm and determination certainly made her one of the most dangerous and formidable women in the country. Although her spying career was brief, and there is doubt among historians about the value of the information she was able to pass on, Rose proved that even through traditional means, women could be effective instruments of war.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett

1862-1931

It was through journalism that I found the real me.

—IDA B. WELLS-BARNETT

Long before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on the bus, a young schoolteacher refused to move from the ladies’ car on the train on the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad. When she was removed from the train she sued—and she won, proving that a woman of color could make her voice heard. Although the decision was later overturned, Ida B. Wells-Barnett kept raising her voice, educating Americans and Europeans about the horrors of lynching and other social injustices that were being heaped on African Americans in the nineteenth century. Ida appeared at a time when the previous generation of black leaders who had led the fight for slavery was now too old to head a new battle to protect the freedoms promised by the Emancipation Proclamation. A new generation was needed and Ida was one who stepped into the breach. In her heyday, she was praised as the Joan of Arc of her people in the black press.

Ida wasn’t one to back down or compromise. She was tough and argumentative, and she clashed with several prominent African American leaders of the time for compromising instead of standing firm. She also clashed with various whites, including temperance advocate Frances Willard. “Temper . . . has always been my besetting sin,” she conceded. She owned newspapers and wrote articles at a time when most women were relegated to writing what was known then as the “women’s page.” She hyphenated her name at a time when most women automatically took their husband’s name. Living in Chicago, she started the first kindergarten for black children. Although she lost a race for the Illinois State Senate, just the fact that she ran, ten years after women won the vote, is a testament to her courage and ambition.

Ida B. Wells was the eldest of eight children, born in 1862 in Holly Springs, Mississippi, to James Wells, a carpenter, and Elizabeth “Lizzie Bell” Warrenton Wells, who were slaves on the Bolling plantation. Although the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 freed slaves held in the Confederate states, Holly Springs, where the family lived, changed hands between the Union and the Confederacy more than fifty times during the war. It wasn’t until the end of the Civil War that the entire Wells family was free.

When Ida was sixteen, yellow fever struck Mississippi, killing Ida’s parents and one of her siblings. Despite tongues wagging at the idea, Ida rose to the challenge of taking care of her remaining siblings and keeping the family together. She took the teacher certification exam and passed with flying colors. Despite the difficulties of raising her six siblings while teaching, Ida still managed to keep up her education, working her way through Shaw University during the summers. Ida knew that education was power, a way out of the backbreaking work of sharecropping and poverty. In 1881, however, she was expelled from Shaw. She never talked about what occurred, but she apparently did something that angered W. W. Hooper, the white president of the college. Ida refused to back down or apologize.

She decided to move to Memphis to live with her father’s stepsister along with several of her siblings. While living in Memphis, Ida availed herself of the social life that was available, taking in lectures, going to the theater, shopping at Menken’s Palatial Emporium, which boasted “Thirty Stores Under One Roof.” She was a regular customer at William’s bookstore, and whenever possible, she attended classes at Fisk University. She enjoyed going to church, not just the black churches but also the white ones, where she would sit in the segregated galleries to hear the sermon.

She started teaching at a country school in northern Mississippi just across the state line from the city. The Federal Civil Rights Act of 1875 that had banned discrimination on the basis of race, creed, or color had just been declared unconstitutional, which led several railroad companies to start practicing segregation. Every day Ida rode the train to work but she never knew from one day to the next whether or not she would be ill-treated, until the day that the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad Company tried to force her to sit in the smoking car when she had paid for a first-class pass. Ida later wrote in her autobiography, “I refused, saying that the forward car closest to the locomotive was a smoker, and as I was in the ladies’ car, I proposed to stay.... The conductor tried to drag me out of the seat, but the moment he caught hold of my arm I fastened my teeth in the back of his hand. I had braced my feet against the seat in front and was holding to the back, and as he had already been badly bitten he didn’t try it again by himself. He went forward and got the baggage man and another man to help him and of course they succeeded in dragging me out.”

White passengers cheered the conductor as he removed Ida from the train. Black newspapers throughout the country reprinted her first article about her railroad court case. With the help of a second lawyer (she was suspicious that her first lawyer had taken money to throw the case) Ida won her lawsuit and was awarded five hundred dollars in damages. However, in 1887, the railroad company appealed the decision to the Tennessee Supreme Court and won, reversing the court’s decision. Ida was required to return the money and to pay two hundred dollars in damages to the railroad.

Ida’s teaching in Memphis schools led her to write articles for the Evening Star, a black-owned newspaper, about the inequalities between the separated black and white schools. She began writing for another local black newspaper, the Memphis Free Speech, where she eventually would become a co-owner and editor. In her editorials, Ida took on the violence against blacks, disfranchisement, the poor school system, and the failure of blacks to fight for their rights. She traveled the country getting subscribers. After she became a co-owner, Ida started printing the paper on pink paper so it would stand out.

She was elected secretary of the Colored Press Association, where she received the nickname “the Princess of the Press.” Her writing style was simple and direct because, as she said in her autobiography, The Crusade for Justice, she “needed to help people with little or no schooling deal with problems in a simple, helpful way.” Eventually fired from her teaching job for writing about the inequalities between black and white schools, Ida became a full-time journalist.

In 1892, a longtime friend, Tom Moss, a respected black store owner, was lynched along with two of his friends after he defended his store against an attack by whites. Wells was outraged, particularly since nothing was done to bring the culprits to justice. She wrote a scathing series of editorials, encouraging black residents of Memphis to leave town and attacking the practice of lynching. She also encouraged those blacks who remained to boycott whiteowned businesses.

“Lynch’s Law,” which became corrupted to “lynch law” and then “lynching,” originated during the American Revolution when Charles Lynch, a Virginia justice of the peace, ordered punishment against those who supported the Tory cause. After the Civil War, lynching became a form of terrorism practiced by white mobs against mostly innocent blacks. Instead of waiting for due process of law, organized mobs would take the law into their own hands. Many of the victims, while being hung, were set on fire or shot.

Lynching was the preferred method to control the African American male population, to keep him in his place, basically poor and illiterate. Between 1880 and 1930, more than three thousand African Americans and some thirteen hundred whites were lynched in the United States. Nine times out of ten, the accused were arrested with no evidence, or what evidence there was turned out to be extremely circumstantial. Confessions were obtained under coercion. Many others were lynched for trivial offenses such as not paying a debt, disrespecting whites, or public drunkenness.

Ida wrote pamphlets exposing the horrors of lynching and defending the victims. She believed that lynching was the central issue facing blacks in the South. Although she wasn’t the first African American to speak out against lynching, she was the first to grain a broad audience. Ida realized that as long as lynching was seen as a way to protect white women’s virtue, black leaders couldn’t address it without sounding defensive or self-interested. However, black women could give effective testimony on the evils of lynching in the name of chivalry.

While Ida was in New York, the office of the Free Speech was destroyed by a mob and she was warned never to return to Memphis. Trying to avoid bloodshed, Ida did not return home, once she heard that black men had vowed to protect her. Instead she moved to Chicago, where she met Ferdinand Barnett, a prominent attorney and widower, whom she eventually married at the relatively advanced age of thirty-three. She also wrote for his newspaper, the Chicago Conservator. After their marriage she became owner and editor.

In 1895, she wrote “The Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynching in the United States: 1892, 1893, and 1894,” which included all her research of the past few years. She started traveling the country asking for support in putting a stop to lynching. People began to ask her to speak at organization meetings and functions. She would spend the rest of her life writing and giving speeches throughout the country and in Europe.

Ida undertook two lecture tours of England at the request of British Quaker Catherine Impey. The goal was to convince the English of the horrors of lynching, since the United States and England had a special relationship. If England spoke out against lynching, perhaps politicians in America would take notice. While in England, Ida launched the London Anti-Lynching Committee. Ida’s tours were a great success, although it led to a rupture between her and one of her sponsors, when she refused to condemn the decision of a woman who fell in love with a man outside her race. She wrote about her tour for the Daily Inter-Ocean in Chicago, becoming the first black woman to be paid as a correspondent for a major white newspaper.

After the birth of her four children, Ida continued to lecture, taking her children with her, asking for babysitters at every stop on her lecture tour. Eventually the demands of motherhood kept Ida in Chicago but she continued to write and speak out about injustice. She refused to walk in the back in women’s suffrage parades because she was black and she fell out with Susan B. Anthony because she dared to get married and start a family instead of devoting herself solely to the cause of suffrage and the establishment of antilynching law.

Although busy raising her four children and her two stepchildren, she found the time to serve as secretary of the National Afro-American Council and she was part of a delegation to President William McKinley to seek justice after the lynching in South Carolina of a black postman. Unfortunately McKinley was too preoccupied by the Spanish-American War and its aftermath to give the matter much attention.

Ida remained active and militant for the rest of her life. She was a founding member of the NAACP, but she later withdrew her membership because she considered the organization not militant enough. In her writing and lectures, she often criticized middle-class blacks for not being active enough in helping the poor in the black community. Her militancy placed her out of sync with more moderate black leaders, such as Booker T. Washington, who were more willing to compromise with whites. Deciding to stick to local issues in the Chicago area, she worked with social reformer Jane Addams to defeat an attempt to segregate Chicago’s public school system. Ida became interested in the settlement movement, in particular the work that Jane Addams had done with Hull House, the first of its kind in the United States. Hull House was essentially a neighborhood center that catered to the recent immigrants in its neighborhoods.

In 1910, she helped found and became president of the Negro Fellowship League, which established a settlement house in Chicago to serve the many African Americans newly arrived from the South. It offered lectures and classes, as well as a kindergarten, a summer day camp, and a meeting place for black women’s clubs and community organizations. To help support the settlement house, she worked for the city as a probation officer, donating most of her salary to the organization. Unfortunately, due to competition from other groups and her own poor health, the league closed its doors in 1920.

Ida started to write her autobiography, The Crusade for Justice, after meeting a young woman who admitted not knowing why Ida was important. Most of Ida’s antilynching work had taken place in the 1890s, before the current generation was born. The newer generation cared less about the struggle. Unfortunately Ida died of uremia poisoning in 1931, at the age of sixty-eight, before the book was finished. In fact she left off not in the middle of a sentence but a word. Edited by her daughter Alfreda Duster, who had saved all her mother’s papers, the book languished for years unable to find a publisher. It was finally published in 1970, helped by the burgeoning interest in African American and women’s history. Ida and her husband’s headstone is engraved with the phrase “Crusaders for Justice.”

During her lifetime, Ida constantly struggled between her militancy and her need to be perceived as a “lady.” Her inability to work successfully with groups meant that she was alienated from movements she founded and she failed to get appropriate credit for her work during her lifetime. For decades after her death, her achievements went largely unsung. It is only in the last forty years that she has gotten the recognition she deserves. In 1990, a U.S. postage stamp was issued, and her work is now studied and taught in high schools and colleges. In 2005, her work was lauded on the floor of the U.S. Congress.

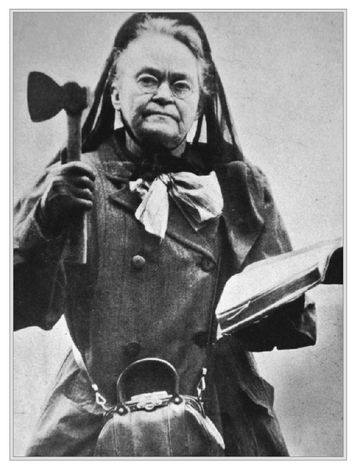

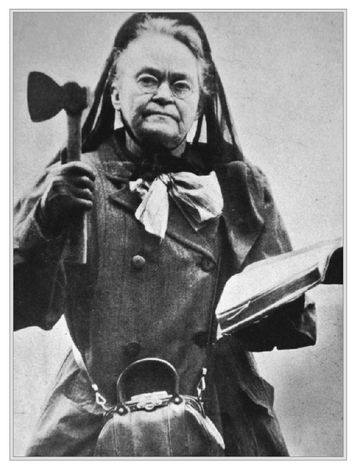

Carry Nation

1846-1911

Truly does the saloon make a woman bare of all things.

—CARRY NATION

Both repellent and fascinating, this hatchet-swinging, Bible-thumping, God-appointed vigilante swung through Midwestern saloons, smashing glass with shrieks of triumph, like an early-twentieth-century “Dirty Harriet.” This self-proclaimed “bull-dog running along at the feet of Jesus” objected not just to drink but also to smoking, the Masons, risqué art, and ostentatious fashion. She took particular delight in assailing people and institutions; not even the office of the President was safe from Carry Nation. Her detractors considered her to be a puritanical killjoy, while her supporters considered her to be a second John Brown. “Savage” and “unsexed” were just some of the words used to describe this grandmotherly woman who stood almost six feet tall. But for Carry Nation, the crusade was intensely personal. She’d seen up close the damage that drink could do.

Carry was born Carrie Amelia Moore in 1846 in Kentucky to a prosperous family. Her mother, frequently ill from constant pregnancies and the strain of taking care of her four older stepchildren, alternated between violent antipathy toward her and smothering her with affection. As a child Carry slept in the slave quarters rather than in the big house with her parents. It was there she found the affection that was lacking from her mother. Young Carry was fascinated by the slaves’ attitude toward religion, their songs and shoutings, and their belief in spirit possession. She kept the secret of their slave meetings, and they rarely tattled on her for her childhood indiscretions.

Carry was a semi-invalid through most of her childhood, suffering from chlorosis, an iron deficiency that manifested a greenish skin color. Biographer Fran Grace believes that Carry’s invalidism might also have been her way of rebelling against being forced to give up her tomboyish ways to conform to society and her mother’s expectations of appropriate female behavior. Being sick kept her from having to assume any responsibility around the house.

The Moore fortunes declined and Carry and her family moved several times, from Kentucky to Missouri and then to Texas. When the Civil War broke out, they had to leave their slaves behind in Texas, while they moved to Independence, Missouri. With no slaves and her mother sick, Carry was forced to take over the household.

When she was eighteen, she met Dr. Charles Gloyd, a Civil War vet who was boarding with her family. Starved of affection, Carry was susceptible to his attentions. Totally innocent, when he kissed her for the first time, she thought she was ruined. But her parents disapproved; not only couldn’t he support her, but they also figured out he was a drunk. Forbidden to speak, Carry and he exchanged letters by hiding them in a volume of Shakespeare.

Eventually her parents relented. Even on their wedding day, the groom couldn’t stay sober, swaying at the altar as he said his vows.

The marriage was a failure; Gloyd preferred drinking with his buddies to spending time with his wife. Carry would often stand outside the Masonic Hall pleading for him to come home. After six months, Carry’s family persuaded her to leave Gloyd and come home. Carry begged Gloyd to sign the temperance pledge but he refused. Their daughter, Charlien, was born in the fall of 1868. When Carry came to retrieve her belongings, Gloyd begged her to stay, predicting his death if she didn’t. He drank himself to death a few months later. Carry was now a widow at twenty-two, with a baby to support. She regretted for the rest of her life that she had left him, believing that she could have saved him if she’d stayed.

Devastated, Carry decided to strike out on her own. She sold her husband’s books and medical equipment and moved to Holden, Missouri. There she lived with her child and mother-in-law. Earning a teaching certificate, she taught for four years until she got into a dispute with a school board official. With no way to support herself, Carry decided her only other option was to marry again. Her second choice was no better than her first. David Nation was an old acquaintance, a lawyer, journalist, and parttime preacher. He was also a recent widower nineteen years her senior with five children. They married three months after his first wife’s death. It was a marriage of convenience; his kids needed a mother, and she was jobless and broke. Three years after the marriage, they moved to Texas to grow cotton, with little success. While her husband struggled to establish himself, Carry became increasingly independent over the years, running two hotels and finally acquiring a degree in osteopathic medicine.

A deeply religious woman, Carry began to have visions and dreams during this period. She felt that she was baptized with the Holy Spirit. In church, she began to break in on the sermons, bursting into prayer or song, and she took to contradicting the preacher when he spoke. Like Anne Hutchinson, she came into conflict with church elders who were dismayed that a woman could suggest that it was possible to have a direct line to God. She was eventually expelled from the church. Although as a child she’d been baptized in the Christian church (Disciples of Christ), she no longer subscribed to one particular creed. Her religious fervor came from a grab bag of influences that she stitched together like a patchwork quilt. It encompassed slave religion, Roman Catholicism, and a few tenets from the Baptist and Methodist churches.

Living in Medicine Lodge, Kansas, Carry became active in the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) and served as a “jail evangelist” to drunks in jail to try to show them a new way. What stuck in her craw was that many saloons in Kansas sold liquor in violation of the state’s prohibition law,

15 and oftentimes legislators and law enforcement officers looked the other way or participated in the illegal activity themselves.

In 1900, she became president of the county WCTU. Realizing that writing letters to legislators wasn’t doing any good in getting the prohibition law enforced, Carry decided to take matters into her own hands. Carry called on the governor’s mansion and reamed him out big-time for not enforcing the law in his own state. She prayed to God for direction and claimed a vision came to her that told her to go to the town of Kiowa. So she took her horse and buggy and headed to Kiowa, armed with bricks to destroy the saloons there. Soon she switched to a hatchet, which was more practical.

Alone or accompanied by hymn-singing women from the WCTU, she would march into a bar and, singing and praying, smash up the bar fixtures and stock. Early on, saloons hired plants and undercover policemen to try to infiltrate the meetings of the “Nation Brigade.” To get around this, brigade members used special code words for entry and wore white ribbons. Moving on to Wichita, she wrecked the bar at the Carey Hotel, one of the most luxurious in the Midwest, causing three thousand dollars’ worth of damages. She spent two weeks in jail but was undeterred. Soon Topeka and Kansas City also felt the fury of her hatchet.

Although Nation believed that her mission was from God, it was still dangerous. She was pushed down, threatened with a gun, beaten and whipped by prostitutes, pelted with rocks and raw eggs. One saloon owner’s wife punched her in the face. Over the course of her career, she was jailed over thirty times, from California to Maine. Even in jail, she was subject to abuse. In Wichita, the judge issued quarantine in the jail, and she was thrown into solitary confinement for days at a time. On more than one occasion, Nation was pursued by a lynch mob. Carry, however, was fully prepared to be a martyr to the cause. In 1901, the state temperance league awarded her a gold medal and the title of “bravest woman in Kansas.”

Carry’s antics, or “hatchetation,” as she liked to call it, made her a nationally known figure. Newspapers eagerly covered her day-to-day activities. Nation was soon receiving two hundred letters a week. Meanwhile her husband divorced her for cruelty and desertion. After the decree came through she said, “Had I married a man I could love, God could never have used me.” Although a divorce tarnished her reputation as a “defender of the home,” Nation now decided that social reform demanded that women see the world as their home. Along the lines of the Salvation Army, Nation organized the Home Defenders Army, creating hatchet brigades. She even tried to reach out to children and teenagers. Despite her reputation as a harridan with a hatchet, Carry was generous to a fault. She collected clothes for the poor and invited them to her house for Thanksgiving and Christmas.

In response to her crusade, saloon owners began to offer “Carry Nation” cocktails while the Senate Bar in Topeka, after reopening, offered a relic from its smashing with every drink. Business boomed so much that the bar had to hire four more bartenders. “All Nations Welcome but Carry” became a popular slogan in bars. After a merchant gave her some pewter hatchet pins left over from Washington’s birthday to sell to pay her legal fees, Nation had her own emblazoned with “Carry Nation Joint Smasher.” They became collector’s items; people who didn’t even believe in her crusade had to have one. Media savvy, she also hawked autographed photos, buttons, her autobiography, and even special water bottles.

In 1903, she had her name legally changed to Carry A. Nation since she believed that was what God had chosen her to do. Carry took her message to the state capitols, not waiting for an invitation to the legislatures of Kansas and California. She once caused the U.S. Senate to grind to a halt while she was forcibly removed from the public galleries for having shouted out her opinions. She started several short-lived magazines with catchy titles like The Smasher’s Mail and The Hatchet. All the money that she made went to serve her causes, the magazines, and homes for the families left behind in poverty by alcoholism.

For the next several years until her death, Carry Nation traveled nationally and internationally, from lecture halls and college campuses to the vaudeville stage. Carry believed that God had called her to take her message to the stage, to reach the masses. “I am fishing. I go where the fish are, for they do not come to me. I found the theaters stocked with the boys of our country. They are not found in churches.”

People either liked her or didn’t but no one was indifferent to her. She made no apologies for her religious fervor, declaring, “I like to go just as far as the farthest. I like my religion like my oysters and beefsteak, piping hot.” Carry Nation appeared at the crossroads between the old world order and the new. She represented old-fashioned moral values of home, hearth, and religion as well as the emergence of the new woman who rejected traditional roles. She both threatened and reassured people at the same time. Even the WCTU both embraced her and kept its distance, applauding her successes yet deploring her methods.

By 1910, Carry had worn out her welcome. After one last speaking tour, she moved to Eureka Springs, Arkansas, buying several homes including one she called Hatchet Hall, a unique woman-centered community for the wives and children of alcoholics, like her daughter Charlien, whose husband turned out to be an emotionally and physically abusive alcoholic. In 1911, she collapsed giving a speech in Eureka Springs Park and was taken to a hospital in Leavenworth, Kansas. She died of a nervous seizure five months later on June 9 and was buried in Belton, Missouri, near her mother. The WCTU later erected a stone inscribed “Faithful to the Cause of Prohibition, She Hath Done What She Could.”

For the short years of her career, Carry Nation was the public face of the temperance movement. Although her tactics could be melodramatic, she influenced lawmakers. As a result of her actions, Kansas at last tried to adhere to its own state laws, and her work eventually led to the Eighteenth Amendment prohibiting alcohol in 1919. Yet during national prohibition, which she had done so much to bring about, and which was abolished in 1933, her grim, iron-jawed figure became a symbol not of reform but of intolerance.

Although Carry died almost a hundred years ago, one can still hear echoes of her message in the moral crusaders who fight what they see as the moral laxity in today’s society, calling for warning labels on DVDs and CDs, supporting antismoking ads, and promoting chastity. No doubt Carry would feel right at home, protesting and swinging her ax at the drive-through liquor stores.