SIX

Amorous Artists

Camille Claudel

1864-1943

All that has happened to me is more than a novel, it is an epic, an Iliad or Odyssey, but it would need a Homer to recount it.

—CAMILLE CLAUDEL

Camille Claudel was only seventeen years old when she met Auguste Rodin in 1882. She and her family had just moved to Paris from the Champagne region where she was born so that she could attend the Académie Colarossi. She was determined to establish herself in Paris and earn her living as a sculptor. Her brother, Paul (who was a little biased), wrote that she was “this superb young woman in the full bloom of her beauty and talent.”

Camille was obsessed at an early age with the wonders and possibilities of clay. She roped in whoever she could—siblings and servants—to act as assistants and models. When other children grew up to move on to other things, Camille did not. By chance, her work attracted the notice of sculptor Alfred Boucher, who gave her some constructive criticism of her work and encouraged the family to move to Paris. When Boucher moved to Florence, after winning the Grand Prix de Salon, he asked his friend Rodin to take his place in guiding his protégée. Auguste Rodin was twenty-four years older than Camille and was finally experiencing the success that had eluded him for so many years of grinding poverty.

Camille was soon hired to work at Rodin’s atelier at rue d’Université along with her friend Jessie Lipscomb. They were the only women, acting as chaperones for each other. Sculpture was not for the faint of heart; it was messy, strenuous, and expensive. It was not a pretty, feminine art like painting. It was manual labor, requiring women to hike up their long, bustled dresses to climb ladders, carrying heavy materials.

Rodin was immediately attracted to the vibrant young sculptor with the wavy chestnut hair and vivid blue eyes, and he noticed her talent as well. He was struck by her originality and her fierce ambition. Rodin himself said about Camille, “I showed her where to find gold, but the gold she finds is truly hers.” Camille quickly became a source of inspiration to Rodin, his model, and his confidante. He soon entrusted Camille with the task of modeling the hands and feet for The Burghers of Calais. Camille’s friend and first biographer, Mathias Morhardt, wrote that from the beginning Camille was Rodin’s equal, not his disciple. “Right away, Rodin recognized Mademoiselle’s prodigious gifts. Right away, he realized that she had in her own nature, an admirable and incomparable temperament.”

Before long Rodin fell passionately in love and pursued her relentlessly. He followed her to England where she was visiting Jessie Lipscomb, and he regularly used Jessie as a go-between when Camille was in one of her unreceptive moods. His letters are far from being those of a sophisticated lover; they are more like those of a teenager in the throes of first love.

23 “You did not come last night and could not bring our dear stubborn one: we love her so much and it is she, I do believe, who leads us,” he wrote to Jessie. From the beginning, Camille blew hot and cold, leaving Rodin in torment. She wasn’t just playing hard to get. While attracted to Rodin, she was worried about being consumed by him, losing her independence, and being forever in the shadow of a great man, her work neglected. She was already giving up so much of herself to Rodin artistically, with her energy, her modeling for him, and working as his assistant.

When she did embark on a relationship with him, she hated sharing him with Rose Beuret, his mistress of over twenty years. They had a son, Auguste, although Rodin refused to legally acknowledge paternity. Rose grudgingly turned a blind eye to Rodin’s affairs, as long as it didn’t interfere with her role as primary mistress. Barely literate, Rose couldn’t compete with a woman like Camille on an intellectual or artistic level. Still she was devoted to him, and Rodin felt a certain loyalty to her; she had been with him since the beginning, sharing the poverty and the worry, modeling for him, and taking care of the little details, leaving him free to work.

Camille and Rodin had a private contract drawn up between them, in regard to their relationship, which wasn’t discovered until 1987 among Rodin’s papers. In the contract Rodin promised to arrange for her to be photographed in her best dress by the celebrated photographer Carjat and to take her to Italy for six months if he won the Grand Prix de Salon. She also wanted him to refuse to take on other female students. In exchange, she agreed to receive him four times a month at her studio. But the most important promise was of “a permanent relationship or liaison, to the effect that Mademoiselle Camille shall be my wife.” None of these promises were kept.

When her family discovered the truth about her relationship with Rodin, she was forced to move out into an apartment of her own. Her relationship with her mother and sister had always been difficult, and now they refused to see her. Her brother, Paul, hated Rodin for seducing his sister. Since Rodin paid the annual rent on her apartment, she was now officially a “kept” woman. Rodin found a new atelier near her apartment on the boulevard d’Italie that had a romantic and mysterious past. George Sand and her lover playwright Alfred de Musset were said to have used it for their trysts. Rodin and Camille worked side by side every day, but at the end of each day Rodin returned to the home that he shared with Rose. During the summer, they holidayed together, secretly staying at the Château d’Islette, in the Loire Valley.

For Rodin, their relationship was one of the great joys of his life. Her face and body haunted his work. He modeled several of the damned souls in The Gates of Hell on her. For Camille, it was more complicated. In one of the few letters that remain between the two of them, she writes a racy little love note: “I go to bed naked to make myself believe you’re here, completely naked, but when I wake it’s no longer the same.” But the postscript states: “Above all, don’t deceive me again with other women.” Models in Paris were like groupies for rock stars: ready, willing, and able. And there were stories of ugly confrontations between Rose and Camille as if the two women were dogs fighting over a particularly meaty bone.

Camille’s fears regarding her work proved well founded. Rodin used his influence with journalists and art critics to promote Camille’s career but it wasn’t translating into commissions. And when she exhibited her work, critics focused on Rodin’s influence on her work, and not enough on her own originality. Those critics who did support her work tempered their praise with comments about how amazing it was that she, a mere woman, could create works of art. The novelist and art critic Octave Mirbeau described her as “a revolt against nature: a woman genius.”

Although her early work showed Rodin’s influence, her pieces were also daring and shocking, particularly in The Waltz (1893), a piece that depicts two barely clothed lovers in a sensual embrace. It was a work of such stunning eroticism that critics considered it improper. “The couple seems to want to lie down and finish the dance by making love,” Jules Renard wrote in his diary. While other female artists, such as Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot, were stuck painting pictures of domestic scenes, mothers and children, Camille created sexually daring sculptures that flew in the face of propriety. The only way that Camille could get a state commission for the piece was to compromise and alter her work, clothing the lovers.

In 1892, after an abortion, Camille ended both her professional and her personal relationship with Rodin. It was clear that he was never going to leave Rose. She was also tired of being treated as just Rodin’s student, as if she had no identity of her own as an artist. Rodin had hoped that they could stay friends but Camille made it clear that she didn’t want to see or talk to him. With him out of the picture, her relationship with her family improved, especially with her brother.

Eventually, after two years, a tentative friendship between Camille and Rodin sprang up. Despite the break, Rodin still intervened on her behalf with influential people whenever he could. In 1895, he asked the scholar Schiel Mourney to “do something for this genius of a woman (no exaggeration) whom I love so much.” He even paid for her assistant when Camille was short of money. The next ten years were the most prolific in her career, as she worked relentlessly. She was determined to make a name for herself and to find her own voice. “You can see that it isn’t Rodin’s anymore, not in any way at all,” she wrote to her brother about one piece. While her earlier work had been made up of large pieces, now she deliberately worked on a smaller scale. She was on her way to creating a new genre of narrative sculpture with pieces like The Gossips, which anticipated pop art. She began to use materials that were difficult to carve, such as onyx.

However, she became increasingly isolated. And since she was no longer working out of Rodin’s atelier, she began to run out of money. Her decision to become something of a recluse, as well as increasing ill health, made taking on pupils or working in another artist’s atelier out of the question. Suspicious and distrustful of women, Camille didn’t socialize with other female artists.

The Age of Maturity is a powerful depiction of her break with Rodin. The sculpture consists of three figures: an old hag leading a middle-aged man off as a young woman is seen imploring him. When Rodin saw the sculpture, he was upset that she would make his private life so public. He used his influence to have a commission for a bronze of the statue canceled. The tenuous threads of friendship were now broken and Rodin stopped supporting her work.

From that moment on, Camille became convinced that Rodin was out to get her. She began to feel that Rodin had fed on her genius like a leech, that all her vital energies had been sapped. In 1905, she had her first retrospective of thirteen pieces at a gallery but it was not well received. She soon began a slow descent into full-blown paranoia. Destroying many of her statues, she disappeared for long periods of time. She directed all her disappointment and anger at Rodin, accusing him of stealing her ideas and of leading a conspiracy to kill her, along with the Protestants, Jews, and Freemasons.

Moving to the Île St.-Louis, she lived alone in a ground-floor flat, surrounded by cats. Desperate for affection, Camille began inviting homeless people to parties whenever she had money; for these she would dress in extravagant outfits and serve champagne. Convinced that Rodin was trying to poison her, she began scrounging in garbage cans for food. After a visit to her studio, her brother, Paul, wrote in his journal: “In Paris, Camille mad. Wallpaper ripped in long strips, the only armchair broken and torn, horrible filth. Camille huge, with a dirty face, speaking ceaselessly in a monotonous and metallic voice.”

Her father tried to help her and supported her financially. But when he died in 1913, no one in her family bothered to tell her. With his death Camille lost her only protector in the family. One week later, on the initiative of her brother, she was admitted to the psychiatric hospital of Ville-Évrard. Although the form read that she had been “voluntarily” committed, Camille was forcibly removed from her ground-floor apartment through a window. She later wrote of “the disagreeable surprise of seeing two tough wardens enter my studio, fully armed and helmeted, booted, menacing. A sad surprise for an artist, instead of being rewarded, this is what I got!” Rodin was shaken by the news of her committal; he tried to visit her but was refused admittance. The Claudels had requested that Camille be sequestered completely after her cousin had brought her plight to the newspapers causing a scandal. She was allowed no communication, correspondence, or visitors apart from her immediate family. Rodin wrote to their mutual friend Mathias Morhardt offering to help by sending her money.

Over the years, as her condition improved, her doctors regularly proposed that Camille be released, but her mother adamantly refused each time, blaming Camille for bringing scandal into their lives. She wouldn’t even countenance a move to an institution near Paris, even when Camille suggested that it would save money. As the years passed, Camille gave up hope of ever being released and became resigned to her incarceration. She died in 1943, after having lived thirty years in the asylum without a single visit from her mother. No one from the family and only a few members from the hospital staff attended the funeral. Her body was never claimed by her family, although her brother, Paul, paid ten thousand francs for Mass to be said for her. After Paul’s death, his son Pierre inquired about removing her body to the family plot, but was told that her remains were buried in a communal grave.

Only ninety statues, sketches, and drawings survive to give any evidence of Camille’s talent. In 1951, Paul organized an exhibition at the Rodin Museum, which was not successful, and she slid into obscurity. That all changed in 1984, when a major exhibition of her work was again shown at the Rodin Museum in Paris, which continues to display her sculptures. It was the first step toward reclaiming her from the dustbin. But it was the 1988 film Camille Claudel, starring Isabelle Adjani as Camille and Gérard Depardieu as Rodin, that brought her story to a wider audience.

It is easy to see why filmmakers were attracted to her story. A beautiful, talented artist falls for one of the greatest sculptors of the nineteenth century and becomes consumed by him to the detriment of her own career, finally succumbing to madness and ending her days in a mental institution. But her story is more complex than that. It is the story of the struggle of women artists in the nineteenth century, trying to overcome the limitations imposed on them by the conservative male establishment.

Isadora Duncan

1878-1927

I am an expressionist of beauty. I use my body as my medium just as a writer uses words.

—ISADORA DUNCAN

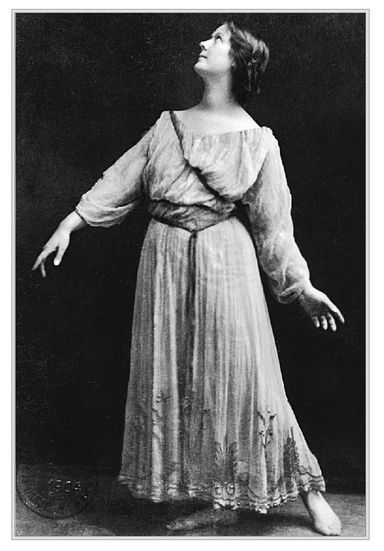

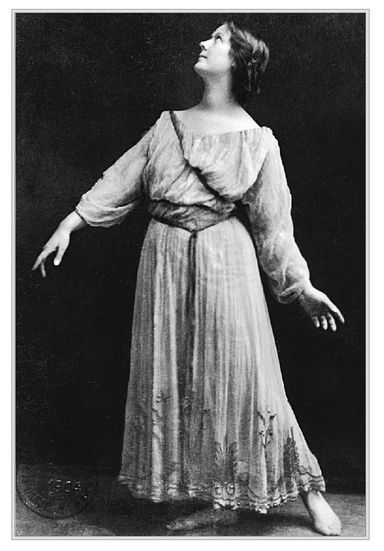

Isadora Duncan claimed that she was born to dance. “If people ask me when I began to dance, I reply, ‘In my mother’s womb, probably as a result of oysters and champagne.’” Isadora’s dancing, her spellbinding influence over audiences, her lovers, and her revolutionary politics made her one of the most notorious artists of her era. Rodin sketched her, Eleanora Duse was her friend, and Stanislavsky went into raptures over her. Audiences were bowled over by her in London, Paris, Berlin, Vienna, Budapest, Moscow, and Athens. Only her native country was immune to her charms and talent.

Isadora danced to classical music before it became the norm in ballet. Eschewing the usual elaborate sets, Isadora danced before simple dark blue curtains, setting a new fashion. Her costumes were as daring as her dancing. Abandoning corsets and stockings, Isadora wore a brief tunic, scandalizing audiences with glimpses of her bare arms and legs. Her dances were never set in stone, the choreography changing as her response to the music changed over the years.

A typical Gemini, Isadora’s life emphasized her dual nature. She lived out of a suitcase, but never lost her taste for luxury. From the lovely auburn-haired sylph of her youth, in middle age she became a fat, lazy hedonist who spent less and less time onstage. Isadora was a woman who dared to live and love. Her lovers were varied: millionaires, actors, musicians, designers, and countless nameless others. “Isadora could no more live without human love than she could do without food or music,” her close friend Mary Desti wrote. “They were as necessary to her as the breath of life.”

She was born in San Francisco when Venus was in the ascendant, blessing her with beauty and charm, according to astrological interpretation. Her father, Joseph Duncan, was a poet, journalist, and deadbeat dad who left his family soon after Isadora was born. After the divorce her mother, Dora, gave piano lessons to make ends meet. They moved from lodgings to lodgings, leaving debts behind, a pattern Isadora would repeat her entire life. Despite the lack of material goods, Isadora’s mother instilled in her children a love of art, reading to them from Shakespeare, Byron, and Isadora’s personal hero, Walt Whitman. The children did whatever they pleased without worry of being disciplined.

Isadora always claimed that she absorbed her first impression of movement from the rhythms of ocean waves. By the time she was six, she was teaching the other children to wave their arms to music. By the time she was ten, she had dropped out of school, convinced that there was nothing that conventional education could teach her. While she had little formal training, she knew the popular dances of her day, and she studied the theories of François Delsarte, although she didn’t like to admit it. The French musician and teacher believed that natural movements were the most genuine and could be used to interpret music. Her dancing incorporated only those movements that were natural to the body, which led her to reject ballet, which she considered abnormal. Dance at the time wasn’t really considered an art. Isadora wanted to change that, to place dance alongside music, sculpture, and painting.

At eighteen, Isadora was convinced that San Francisco was too provincial to understand her art. The family moved to Chicago with only a small trunk, twenty-five dollars, and some jewelry. Isadora auditioned in her cute little white tunic for various producers but there were no takers. After months of no work, Isadora got an audition at the Masonic Temple Roof Garden. The manager, however, told her that she could perform her original dances if she also performed what they called a “skirt-dance” number. Isadora lasted three weeks before she quit, disgusted at having to “amuse the public with something which was against my ideals.”

Next stop was New York. If she could make it there, she could make it anywhere. After two years touring with Augustin Daly’s theater company, she met a young composer with whom she gave five solo concerts at Carnegie Hall. Things began to turn around when Isadora was taken up as a sort of pet by wealthy society matrons who invited her to dance in Newport and at their mansions on Fifth Avenue. High society applauded, but it didn’t pay the rent. The final straw for the family occurred when the hotel where they were living burned, along with all their possessions. It was time to make her mark in Europe, where she was convinced her art would be appreciated. With only three hundred dollars, the family had to cross the ocean on a cattle boat. Isadora’s mother cooked for the crew to help pay for their passage.

London and Paris proved to be more hospitable. She made her Paris debut, and audiences adored her. It was in Paris that Isadora developed the idea of dancing from the solar plexus, whereas classical ballet emphasized dancing from the spine. Soon she went off on a tour of Hungary and Germany; in Berlin, the audience mobbed the stage and refused to leave. Newspapers were filled with interviews with “Holy Isadora.” One night she improvised to Johann Strauss’s “Blue Danube” waltz, which was a huge hit. Wagner’s son invited her to dance at Bayreuth in Tannhäuser, but her new style clashed with the ballet dancers hired to dance the Bacchanal with her. In Greece, Isadora danced among the ruins.

Isadora not only influenced the future and evolution of modern dance but also the first modern ballet company, the Ballets Russes. Both impresario Sergei Diaghilev and the choreographer Michel Fokine were taken by her on trips to St. Petersburg in 1905 and 1907. Diaghilev thought she gave an irreparable jolt to classical ballet in imperial Russia. Fokine wrote that “she reproduced in her dancing the whole range of human emotion.”

She founded her first school, in Grünwald, Germany, to teach not just dance but also what she called “the school of life.” “Let us teach little children to breathe, to vibrate, to feel and to become one with the general harmony and movement of nature. Let us first produce a beautiful human being, a dancing child.” While Isadora was inspirational, she wasn’t great at communicating her techniques. That was left to her sister Elizabeth, who taught at the school for years until it closed. It was the first of many schools that Isadora would found in her lifetime. The school gave rise to her most celebrated troupe of pupils, dubbed the Isadorables, who eventually took her surname and later performed both with Duncan and independently.

But artists cannot live by acclaim alone. Who would finally initiate her into the delights of Aphrodite? For such a free spirit, Isadora was still a virgin at twenty-five. In Hungary, she was finally introduced to the pleasures of the flesh when she met the actor Oscar Beregi, whom she immortalized as Romeo in her autobiography. They met at a party in her honor. Beregi was twenty-six, tall, dark, and handsome. Soon he was declaiming poetry from Ovid and Horace, backed by a chorus, in between her dances. Isadora was in love but Beregi expected her to give up her career to support his. Isadora was determined to stay free. Still, all her life she would be torn between love and her art.

The great love of her life was probably the stage designer Edward Gordon Craig. Gordon Craig was a creative genius as well as a misogynistic bastard. The father of eight, he’d already abandoned a wife and a mistress and was now living with his commonlaw wife. Introduced after one of Isadora’s shows, he soon invited her up to see his etchings and she stayed for four days. She fell madly in love with him. “A flame meets flame; we burned in one bright fire.” Isadora abandoned her art for a time, lost in passion. She bore him a child, Deirdre, in 1906. The relationship eventually crashed and burned over their fierce jealousies of each other.

The longest and most enduring relationship of her life was with Paris Singer, the sewing machine heir. Named after the city of his birth, Singer was tall, blond, bearded, and looked like a Nordic god. She called him Lohengrin in her biography, after Wagner’s hero, and later claimed that he was the only man she’d ever loved. He was rich, worldly, and a generous patron of the arts. He brought luxury and devotion into her life. Once again, her career took second place to her new love as she spent time sailing on his yacht or at his villa. “I had discovered that love might be a pastime as well as a tragedy. I gave myself to it with pagan innocence.” She gave birth to their son, Patrick, in 1911.

On April 19, 1913, Deirdre and Patrick drowned when the car they were riding in accidentally rolled into the Seine. Isadora’s life could now be divided into two parts: before and after the tragedy. She never spoke of her children again, and for years afterward the sight of a blond child moved her to tears. Following the accident she went to Corfu with her brother and sister to grieve and then sought solace with her friend Eleanora Duse at her villa in Viareggio, Italy. Isadora didn’t dance for two years. When she returned to the stage, Europe was at war, and Isadora infused her dancing with her grief, channeling the sorrows of the world. She added an impassioned rendition of “La Marseillaise” to her repertoire.

She broke with Singer, who was turned off by her habit of making public scenes. The final blowup came after he booked Madison Square Garden for a performance by her school. When Isadora heard the news, she sarcastically replied, “What do you think I am? A circus? I suppose you want me to advertise prize fights with my dancing?” Singer was livid; he got up and walked out. Isadora was sure that he would be back but it was over. He cut off her funds and refused to see or speak to her for a long time.

Professionally, Isadora’s pupils caused her both pride and anguish. The Isadorables were subject to ongoing hectoring from Duncan over their willingness to perform commercially. Where once she claimed not to be jealous of the dancers, she now considered them to be her rivals and envied their success. Only Irma Duncan (no relation) would be the most faithful of her acolytes, following her to Russia in 1921, where she taught in Moscow for seven years. Returning to the States, Irma continued to teach Duncan’s techniques until her death in 1977.

America had never embraced her with open arms the way Europe had. Her atheism, love affairs, illegitimate children, and lack of embarrassment were a little out-there for early-twentieth-century America. During the war, she moved herself and her students to safety in New York, where she hoped to open a school, but she was too outspoken about America intervening in World War I and about free love, and she flouted the puritanical codes of the country. Even her native city, San Francisco, gave her the cold shoulder. Isadora became convinced that Americans had little appreciation for art and beauty, or at least her version of them.

By the end of her life, Duncan’s performing career had dwindled and she became more notorious for her financial woes, and all-too-frequent public drunkenness, than for her dancing. There was an ill-fated attempt to start a school in Soviet Russia and a disastrous marriage to Sergei Esenin, a mentally unstable poet seventeen years her junior, which ended with his suicide. Her espousal of communism made her persona non grata in the United States. She had lived long enough to see her style and technique be considered old-fashioned and perhaps a little bit out of touch. Barefoot dancing was no longer new and innovative. She spent her final years moving between Paris and the Mediterranean, running up debts at hotels. By the time she sat down to write her autobiography, she hadn’t danced in three years. Her love of luxury eventually led to her death, in Nice. Settling into her seat as a passenger in the Bugatti she was thinking of buying, with a handsome French-Italian mechanic, her long, embroidered Chinese red scarf became entangled around one of the vehicle’s open-spoked wheels and rear axle. When the car sprang forward, the scarf tightened, snapping her neck. Her last words had been “Adieu, mes amis, Je vais à la gloire.” (“Good-bye, my friends, I go to glory.”)

After lying in state in Nice and Paris, her funeral was scheduled on what was the tenth anniversary of America’s entry into World War I. The American press, who had never understood her, wrote that her funeral cortege was barely noticed as the American Legion parade wended its way down the Champs-Élysées. There was no report of the ten thousand people who gathered at the cemetery or the one thousand who crowded the crematorium as her favorite music played. Her ashes were placed next to those of her beloved children at Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.

There is no film of Isadora dancing, which is perhaps as she would prefer. Isadora claimed that she preferred to be remembered as a legend. She died before the advent of sound recording, which would have allowed the cameras to capture her performance with the music that inspired it. One can only get a sense of the glory and passion of her art from still photos, the dancers that she inspired, and the reviews and memories of those who saw her dance. While her schools in Europe did not survive for long, her work can be felt in the many dancers and choreographers that she influenced.

Josephine Baker

1906-1975

What a wonderful Revenge for an Ugly Duckling!

—JOSEPHINE BAKER

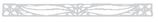

On the night of October 2, 1925, audiences had no idea what to expect when the curtain rose at 9:30 p.m. at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, on a new show from America called La Revue Nègre. Then Josephine Baker burst onto the stage, letting rip with a fast and loose Charleston. At the end of the show, she reappeared naked except for beads and a belt of pink flamingo feathers between her legs, carried upside down in a split, by her partner, bringing a little bit of Africa to France. It was the event of the season. Critics in Paris thumbed through their thesauruses trying to outdo themselves with animal metaphors and exotic imagery to describe her performance.

Overnight Josephine Baker’s life had become something like out of the fairy tales that she had absorbed as a child.

Born illegitimate in the slums of East St. Louis, from childhood she was made to feel like an outsider in her own family because she was lighter skinned, while her mother and half siblings were dark. A poor student, she began making funny faces as a defense mechanism. What began as a way of coping later turned into a way for Josephine to make a living. By the age of twelve, she had dropped out of school, living on the streets, scrounging for food in garbage cans. A natural dancer, she learned all the latest steps in the streets of St. Louis. “I was cold and I danced to keep warm, that’s my childhood,” she later wrote. Dancing on the street corner to make money brought Josephine her first success. Soon she was playing vaudeville houses, working behind the scenes as a dresser. By the age of fifteen, she had married and discarded two husbands. It was her second husband who gave her the last name she would use for the rest of her career.

Rejected after she auditioned for a new Broadway musical called Shuffle Along because she was too young, too thin, and too dark, Josephine became determined to join the show. When she was offered a job as a dresser, she took it; she learned all the songs and dances, and when a chorus girl took sick, Josephine stepped in. Happy to be onstage, she was a sensation, stealing scenes from more experienced performers. She fed off the energy of the audiences, improvising dance steps, the audience giving her the unconditional love she’d never received at home. Kicking up her heels, Josephine continued to knock ’em dead in the Broadway show Chocolate Dandies and performed at the Plantation Club.

In 1925, she was offered the chance to go to Paris and never looked back. She had heard that life was better there for blacks and the two hundred bucks a week didn’t hurt. At first Josephine wasn’t too keen when she found out she was to perform half naked. It wasn’t the glamorous image she was aiming for. She wanted to be seen as a singer, or at least wear a dress. But she soon came around when she realized the alternative was a one-way ticket back home. She was excited, though, when the artist Paul Colin, who later became her lover, used an image of her, rather than the star, Maude de Forest, for the poster advertising La Revue Nègre.

As Josephine shook and shimmied on opening night, her dancing verged on the obscene, titillating some and offending others. Her dancing emphasized her rear end, a part of the human anatomy that had once been hidden by bustles and skirts. She made it an object of desire. One critic called her dancing the “manifestation of the modern spirit.” Another wrote, “She is constant motion, her body like a snake.” People were so fascinated by her mugging, and how little she wore, that the difficulty of the choreography was often overlooked. Josephine used her press clippings to learn French, amused by the high-flown language used to describe her dancing. She was smart enough to know that it was all hyperbole, that they thought she was from Africa and not the wilds of St. Louis. “The white imagination sure is something,” she said, “when it comes to blacks.”

Paris was in the grip of “Negromania”; they were crazy for “Le Jazz Hot” and anything African and primitive. Josephine was the living, lusty embodiment of white French racial and sexual fantasies. She was “the Bronze Venus” and “the Black Pearl.” Picasso, who painted her, called her “the Modern Nefertiti.” They adored her; women bobbed their hair à la Josephine and tanned their skin. Baker wasn’t just a success in Paris; she was a hit in Berlin, where the great theater director Max Reinhardt offered to take her under his wing, to help her become a great actress. It was tempting but Josephine went back to Paris to the Folies Bergère. This time she was the featured star, performing the “Danse Sauvage” wearing nothing but a necklace, a skirt made of bananas, and a smile.

Josephine made the most of her new status as a sex symbol, sharing her charms with whoever struck her fancy, from chorus boys to industry titans. She became a notch on the belt of writer Georges Simenon, test-drove the Crown Prince of Sweden, and hobnobbed with the architect Le Corbusier. Because she didn’t need a man to support her, she could indulge just for the pleasure. Whether it took ten minutes or an hour, Josephine was always in the driver’s seat. She accumulated dozens of marriage proposals and forty thousand love letters in just one year. The ugly duckling had turned into a swan, and now men couldn’t tell her enough how beautiful she was. She lapped up their attentions like a starving child.

Josephine quickly became the most successful American entertainer working in Paris. Photographs of her sold like hotcakes, and people bought Josephine Baker dolls, wearing the little banana skirt, by the thousands. She became a poster girl for the Roaring Twenties in Paris. Soon Josephine added movie star to her list of accomplishments, appearing in three films, Siren of the Tropics (1927), Zou Zou (1934), and Princess Tam Tam (1935), which were only successful in Europe. In each one, Josephine played a variation on the noble savage, an exotic creature who sacrifices and loses at love.

But sensing that the city would soon get tired of her shtick, Josephine realized that she would need to reinvent herself if she was going to continue to be a success. She was helped by her manager and lover Giuseppe Abatino, called Pepito, a former stonemason. He played Pygmalion to her Galatea, teaching her how to dress and act in society, training her voice and body, and sculpting her into a highly sophisticated and marketable star. When she moved on from the Folies Bergère to the Casino de Paris she had a whole new act. Descending a grand staircase, wearing a tuxedo, she now sang French torch songs, including her signature number “J’ai Deux Amours.” Josephine had reinvented herself from an exotic savage to a sophisticated French chanteuse, becoming “La Bakaire.”

She played the role of star to the hilt, adding an accent over the e in her last name to appear more French. Josephine wore couture and expensive jewelry and she spent hours after shows signing autographs. At night she was chauffeured from one lavish party to the next in a snakeskin-upholstered limo. She once showed up at a nightclub with her snake Kiki wrapped around her neck. Given a cheetah named Chiquita as a pet, Josephine and the animal, wearing a twenty-thousand-diamond collar, became a familiar sight on the streets of Paris and Deauville. She bought a château fit for a princess, but offstage, Josephine, wearing housedresses, lived a simple life in the country with her menagerie of animals.

Her stunning success did not come without its price. She was often the only black performer onstage surrounded by whites. And the racism she had left America to escape often reared its ugly head. During a tour of Germany and Austria, Nazi protesters tried to bar her from performing. Other performers in France, both white and black, resented her success. Although she became more French than the French, there were barriers that she was never able to overcome. Throughout her life Baker was criticized for turning her back on her people. While some gloried in her success, seeing her triumphs as their own, there were others who felt that Josephine had abandoned her country and her race.

After ten years in France, she decided that it was time for her to return to Broadway. Pepito arranged for her to appear in the 1936 Ziegfeld Follies, making her the first and only black female ever to appear in the show. When the show reached New York, the reviews were devastating. Audiences and critics were used to seeing black performers as either mammies or blues singers; they were not interested in seeing a sophisticated black woman onstage. To them Josephine was just an uppity colored girl. At the St. Moritz Hotel on Central Park South, where she was staying, she was asked to use the service entrance when she came and went. Josephine blamed Pepito for the whole debacle. He left for Paris and died of cancer before they could make up. Hurt and disillusioned by the experience, Josephine had learned a hard lesson: that America would never look at her without seeing her color.

With Europe on the brink of war in 1939, Josephine was eager to do her part for her adopted country. “It is France which made me what I am,” she declared. The Deuxième Bureau, the French military intelligence group, was reluctant at first to use her because of the whole Mata Hari debacle during World War I. Josephine convinced them of her sincerity. She would have no official role except that of “honorable correspondent.” Because of her fame, Josephine rubbed shoulders with people with high profiles. She was able to attend parties at the Italian embassy and pass on any gossip that might be of use. She also helped the war effort in other ways, by sending Christmas presents to soldiers and helping people in danger obtain visas and passports to leave France.

When France fell to the Germans in 1940, she fled to her Château des Milandes, gasoline stored in champagne bottles packed in the trunk of her car, with her maid and her dogs. Soon she was joined by Belgian refugees and others who were working for the resistance. Because she was an entertainer, Josephine had an excuse to move around Europe. She smuggled intelligence coded in invisible ink within her sheet music. In 1942, she went to North Africa under the guise of recuperating from pneumonia, but the real reason was to help the resistance. From her base in Morocco, she toured Spain and North Africa, entertaining Allied troops, pinning notes with any information she gathered in her underwear. For her work during the war, Josephine was awarded the Cross of War and the Medal of the Resistance with rosette, and she was made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor by Charles de Gaulle.

Happily married to her fourth husband, she decided to tour America once again, but this time with her own show. She refused, however, to perform before segregated audiences in Las Vegas and Miami. For her pains she was considered to be politically dangerous, demanding, and difficult. But things got worse after she charged the Stork Club in New York with racism. She had come into the club with two white friends and experienced less than stellar service from an indifferent waitstaff. Used to being treated like a star, Josephine was appalled. She immediately got on the horn to the NAACP to picket the club. Influential columnist Walter Winchell, who was there that night, took her to task in his column. He accused her of being anti-American and a communist sympathizer. Her controversial image now threatened her career. Concerts were canceled and Josephine went back to France.

Unable to have children of her own, Josephine adopted what she called her “Rainbow Tribe.” Initially she had planned on adopting only two or three children. However, once Josephine got started, she couldn’t stop, eventually adopting twelve children in all, in various hues and nationalities. Living at Château des Milandes, a sprawling three-hundred-acre estate, with her children and an enormous staff, Josephine had to keep touring to pay for the upkeep. Long before Branson or Dollywood, Josephine cooked up the idea of turning her home into a tourist attraction/theme park, complete with a simulated African village, a wax museum, a foie gras factory, a patisserie, a J-shaped swimming pool, and even a nightclub where she would be the star attraction. But by the late 1960s, Josephine was deeply in debt. Creditors seized the property and belongings and sold them at auction. Until the bitter end, like a tigress protecting her young, Josephine tried to hold them off until the gendarmes had to forcibly remove her. Help came from her own fairy godmother, Princess Grace of Monaco, who offered financial assistance and the use of a villa.

But in 1975, at the age of sixty-eight, when most women are collecting social security, Josephine came roaring back with a retrospective revue at the Bobino in Paris, celebrating her fifty years in show biz. She had already conquered Carnegie Hall and the Palace in New York, and was in great demand from spectators including Mick Jagger, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, Sophia Loren, and Diana Ross. The revue opened to rave reviews but Baker didn’t live to savor her triumph. Four days later, she was discovered lying peacefully in bed, surrounded by her glowing notices. She had fallen into a coma after suffering a cerebral hemorrhage. Her funeral was held at the L’Église de la Madeleine; she was the first American woman to receive full French military honors at her funeral. The streets were thronged with thousands of fans paying homage to La Bakaire one last time.

Billie Holiday

1915-1959

She whispered a song along the keyboard . . . and everyone and I stopped breathing.

—FRANK O’HARA, “THE DAY LADY DIED”

Death. Pain. Sadness. When people think of Billie Holiday, these are the words they invariably use. The 1972 film Lady Sings the Blues reinforced the portrait of a childlike woman with no greater ambition than to “sing in a club downtown” who was derailed by drugs but saved by the love of a good man. It’s true that in her four decades, she knew more sorrow and tragedy than joy or love. But there was more to Billie Holiday than the portrait of a singer, gardenia tucked behind her ear, clutching the microphone like a lover. She was a musical genius, who pioneered a new way of singing. Although she couldn’t read music, Billie only had to hear a song once before she could sing it.

Her voice ranged over little more than an octave, but she used it the way a musician plays an instrument, patterning her phrasing in unexpected ways. Her vocal style, strongly inspired by jazz instrumentalists, manipulated phrasing and tempo. Singing just behind the beat, she would take a song and twist it in unexpected ways. Rarely did she sing a song the same way two nights in a row. “I hate straight singing,” she once said. “I have to change a tune to my own way of doing it. That’s all I know.” Critic John Bush wrote that she “changed the art of American pop vocals forever.” Duke Ellington called her “the Essence of Cool.” Frank Sinatra claimed that Holiday “was and still remains the greatest single musical influence on me.”

It was a long way from Philadelphia, where she was born Eleanora Fagan on April 17, 1915. Her mother, Sadie Fagan, and her father, Clarence Holiday, were barely out of their teens when she was born. Despite what she wrote in her autobiography, her parents never married and Billie didn’t see much of her father until she moved to Harlem and started singing in the clubs. She was farmed out to relatives in Baltimore almost from birth, who made her feel unwanted, never giving her the security of a home life. By the time she was eleven, she’d been busted for truancy, sent to reform school, and raped by a neighbor. She had to learn to be tough to survive.

It was at her cleaning job in a brothel in Baltimore that Eleanora first heard jazz being played on the Victrola in the parlor. She nearly wore the record out. Louis Armstrong and Bessie Smith were her first influences. Years later, she would remember, “Sometimes the record would make me so sad I’d cry up a storm. Other times the damn record made me so happy I’d forget about how much hard-earned money the session in the parlor was costing me.” In 1929, Eleanora left Baltimore behind for New York City. Reunited in Harlem, mother and daughter were soon working in a local whorehouse. In 1930, they were both busted but while Sadie got off with a fine, Eleanora was sent to a workhouse for one hundred days. When she got out, Eleanora decided that she “wasn’t going to be no damn maid” and she wasn’t going back to hooking.

That only left singing as an alternative. Harlem had become not just a haven for African Americans, the promised land of jobs and freedom, but it was also a mecca for jazz, not only at clubs, like the Cotton Club, that catered mainly to white patrons, but also places like Small’s Paradise. Eleanora got a job waiting tables and singing for tips at a club called Pod and Jerry’s. Most of the girls would pick up their tips by grabbing them between their thighs, but Billie was too dignified for that and refused.

She began to pick up more and more small gigs as word of mouth spread about the talented young singer. At the age of fifteen, she changed her name to Billie after her favorite movie star, Billie Dove, and Holiday after her father. By this time, Clarence Holiday was working with the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra. But the relationship between the two was awkward. Although he was proud of her talent, Holiday didn’t like being reminded of his past, or that he was old enough to have an adult daughter.

Billie was eighteen when she was spotted at a club called Monette’s by the man who was most important in launching her career. John Hammond, a critic and record producer, came every night for three weeks to hear her sing. “She was the best jazz singer I had ever heard,” he later wrote. Before long he had her cutting her first record as part of a studio group led by Benny Goodman, who was then just on the verge of making it big. In 1935, Billie recorded four sides that became hits, including “What a Little Moonlight Can Do,” which landed her a recording contract with Columbia Records. She also made her debut that same year at the Apollo Theater, the mecca of music in Harlem. Despite her stage fright, she made a huge impression on the audience.

Billie’s voice wasn’t as big as Ella Fitzgerald’s or Bessie Smith’s, but she made the most of what she had. She mesmerized the audience with the stories she told with her voice. When Holiday came onstage, she sang, and then she left. She didn’t entertain the audience between songs with jokes and witty banter. If she felt like it, she gave an encore. Despite the title of her autobiography, Lady Sings the Blues, if you had asked her, she would have told you that she was a jazz singer. Her singing style, one writer wrote, was, “as fiercely concentrated as oxyacetylene flame.” She would later say that it took about ten years for people to catch on to what she was doing.

Now that she was making money, Billie upped her game, trading her tight, trashy stage costumes for a more elegant, refined image. Her signature look came about by accident. One night before a show, she burned her hair with a curling iron. A gardenia was procured to cover the damage. Liking the look, she kept it.

In a few short years, Billie had gone from singing for tips to touring with Count Basie’s orchestra, playing the Apollo, and making a short film with Duke Ellington. She became one of the first black performers to integrate an all-white band when she sang with Artie Shaw. But life on the road was hard. In Detroit, the management of the Fox Theater demanded that she wear darker makeup to blend in better with musicians in Count Basie’s band. Billie couldn’t stay at the same hotels or eat with her white fellow musicians in restaurants and cafés.

Billie also started to get a reputation for being difficult, complaining about her salary and working conditions. She parted ways with Count Basie when she refused to sing songs she didn’t like. Song pluggers were peeved with the liberties she took, saying that she was “too artistic.” She fell out with Shaw when she felt that he didn’t stick up for her enough with the management of the Lincoln Hotel in New York after the owners insisted that she use the tradesmen’s entrance so that customers wouldn’t think that blacks were staying there.

In 1939, she became the first black woman to open at an integrated club, Café Society, downtown in Greenwich Village. That same year Barney Josephson, the owner of Café Society, introduced Billie to the Abel Meeropol song “Strange Fruit.” Legend has it that Billie at first had no idea what the song was about. Given that black newspapers carried stories of lynching and Billie had toured the Deep South, it’s impossible to believe she was that ignorant. At twenty-four, like most blacks in the United States, she knew the sting of racism.

“Strange Fruit” was Billie’s contribution to protesting racial violence. It may have been written by a white man, but Billie gave it life. “The first time I sang it, I thought it was a mistake. There wasn’t even the patter of applause when I finished. Then a lone person began to clap nervously. Then suddenly everyone was clapping.” The song forced the middle-class white audience to confront the reality of racism. Josephson added to the drama by insisting that Billie close her three nightly sets with the song; all service was halted, and the only light was a spotlight that illuminated her face.

Billie’s own label, Columbia, wouldn’t record the song; the executives were too fearful of antagonizing Southern customers. Hurt and angry, she took it to Milt Gabler, the owner of Commodore Records, a small label that was run out of a record store. Gabler jumped at the chance, paying Billie five hundred dollars for “Strange Fruit” and three other songs; he later paid her an additional thousand dollars. Released on July 22, 1939, “Strange Fruit” rose to number sixteen on the record charts, selling ten thousand copies its first week.

For Billie, “Strange Fruit” changed everything. For the first time, she enjoyed the critical praise from the mainstream press that had eluded her for years. People were beginning to know her name outside of the music world. The song remained a fixture in her repertoire until her death, continuing to have resonance for her, and she never lost her passion for singing it. Once she even walked off the stage at Café Society when she felt the audience wasn’t paying sufficient attention to the song, flipping up her dress and flashing her bare behind at them. She had a clause put into her contracts that she could sing it whenever she wanted. Although other singers performed the song before and since, it has her fingerprints all over it. But not everyone was happy at the song’s success. John Hammond felt that the song ruined her career, that she began to take herself too seriously, losing her artistry and sparkle.

By the 1940s, Billie was one of the most desired singers in the small clubs on West Fifty-second Street (aka Swing Street), making a thousand dollars a week. She moved to Decca Records, continued to play clubs big and small around the country, and made a film with her idol Louis Armstrong. Vocally she was more assured than ever, refining her sound, with no excess gestures or emotions. But it was also a decade of bad choices and bad men. Billie seemed to be fatally attracted to low-life hustlers who exploited her, stole her money, and supplied her with drugs—men like her first husband, Jimmy Monroe, a sharp, flashy dresser she married in 1941.

Although Holiday had often indulged in marijuana, as did a lot of musicians, and could drink any man under the table, it wasn’t until sometime in 1943 that she started to use heroin. It was as prevalent among the musicians she hung out with as reefer. Billie seems to have started for the same reason a lot of people do: for the thrill of it. She had no idea the toll her addiction would take on her life and her career. “I had the white gowns and the white shoes. And every night they’d bring the white gardenias and the white junk.” At one point, she claimed that she was spending five hundred dollars a week on her habit. The drugs were giving her a Dr. Jekyll and Ms. Hyde personality. She once went after a naval officer with a broken bottle after he called her a “nigger.” She dumped Monroe and took up with Joe Guy, a musician and drug addict who could supply her with the drugs she craved.

After her mother’s death in 1945, Billie had fewer people in her life who tried to protect her, the way Sadie had done. Although they had a tense relationship at times, Sadie had always been there for her daughter. With her mother gone, Billie was now an orphan, and she never quite got over her death. Sinking deeper into drink and drugs, she became even more dependent on the men in her life to keep the loneliness at bay. She tried rehab after her agent threatened to drop her but it didn’t last.

In 1947 Billie was arrested for narcotics possession after federal agents searched her hotel room in Philadelphia. “It was called ‘The United States of America versus Billie Holiday.’ And that’s just the way it felt,” Holiday recalled in her autobiography, Lady Sings the Blues. On the idiotic advice of her agent, she pled guilty and waived her right to counsel, probably thinking they would just send her back to rehab. Despite the pleas of the prosecutor, Billie was sentenced to a year and a day and sent to Alderson Federal Prison Camp in West Virginia. She was released seventytwo days early for good behavior. Eleven days after her release, she made her comeback in a sold-out concert at Carnegie Hall.

But because of her conviction, Billie’s cabaret license was revoked, making it difficult for her to get work except in concert halls and theaters. Almost a year later she was arrested again, this time for possession of opium. Her current lover, another thug named John Levy, gave her all his drugs to hold after he got a tip that narcotics agents were coming to arrest him. Before she could do anything, they were both arrested. She beat the charges; the jury acquitted her, deciding that Levy had framed her. But it would not be her last arrest.

There were still some triumphs in her remaining ten years—several new recordings, this time with Verve—but also another abusive marriage, to mob enforcer Louis McKay, who at least tried to get her off the drugs but to no avail. There were missed performances, and some nights Billie clutched the microphone like it was a lifeline. She forgot the lyrics, was inaudible, or fell behind the beat. On other occasions, a miracle would occur, and she would hold it together, producing the magic the way she used to.

In 1954 Billie finally got to go to Europe. She loved touring in Europe. Everywhere she went, she was treated like royalty. But by her second tour, the ravages of the drugs, alcohol, and smoking had taken a toll on her voice. Holiday compensated with a new emotional truth in her singing. Still she was booed in Italy, and the rest of her engagements there were canceled. At the end she was singing in Parisian nightclubs for a percentage of the door.

On May 31, 1959, she was taken to Metropolitan Hospital in New York suffering from liver and heart disease. When a nurse found heroin in her room, she was arrested for drug possession as she lay dying, and her hospital room was raided by authorities. Police officers were stationed at the door to her room. Holiday remained under police guard at the hospital until she died, from cirrhosis of the liver, on July 17, 1959. She died with seventy cents in the bank and $750 on her person.

Her funeral was held at the Church of St. Paul the Apostle on Sixtieth Street and Ninth Avenue. It was a full Catholic Requiem High Mass, with a full choir providing the music. Lady Day was dressed in her favorite pink lace dress and gloves. Three thousand people attended the funeral; five hundred others stood outside the church.

Although she never had a number one hit or was the most popular singer, Billie Holiday probably influenced more musicians than any other singer in the twentieth century. During her career, Holiday collaborated and earned the respect of some of the most noted names in music, a roll call of jazz greats. Her legacy lies not in her story but in the music that she left behind.

Frida Kahlo

1907-1954

They thought I was a surrealist but I wasn’t. I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality.

—FRIDA KAHLO

Frida Kahlo once wrote that she had suffered “two grave accidents in my life. One in which a streetcar knocked me down . . . The other accident is Diego. And he was by far the worst.” Ouch, that’s harsh. While there is an element of truth in that statement, it’s far more complicated than that. The streetcar accident that Frida suffered at the age of eighteen left her with a lifetime of pain, but it turned her in a new direction. Painting brought her back to life, and in her pain she found one of the most important themes in her work. Diego Rivera was no prize as a husband, chronically unfaithful, but he gave her support both financial and emotional, opened doors for her, and helped to shape her talent.

Frida’s parents, Guillermo Kahlo and Matilde Calderón y Gonzalez, were an odd couple from the start. He was a German Jewish atheist widower, with two children, who suffered from epilepsy. Matilde was a devoted Mexican Catholic who never got over the death of her first love, another German, who committed suicide in front of her. Their third daughter, of four, was born Magdalena Carmen Frieda in July 1907 in La Casa Azul (the Blue House), in Coyoacán, a small town on the outskirts of Mexico City. Frida later liked to claim that she was born in 1910, the year of the Mexican Revolution, to emphasize her bond with the rebirth of Mexican culture.

When Frida was six, she contracted polio, keeping her bedridden for nine months. The illness left her with a withered right leg and a limp. Her classmates at school taunted her, calling her Frida pata de palo (Peg Leg Frida). For the rest of her life she wore long skirts or pants to hide her leg. Her illness left her with a sense of solitude, but it fired up her imagination. In 1922, she passed the entrance exam for the most prestigious school in Mexico, the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria. Her childhood turned Frida into a tough, rebellious teenager. At school she became involved with leftist politics, cut classes that bored her, tried to get teachers fired that she felt weren’t up to the job. By the time she was seventeen, she’d been seduced by both an apprentice engraver who taught her to draw, and a female librarian at the ministry of education. She also became fascinated with Diego Rivera when he was painting a mural in the school’s auditorium, sitting quietly watching him work. Later she embellished this version, claiming to have played tricks on him, spying on his liaisons with models. When her friends asked what she saw in him, she claimed that she would have Diego’s child when the time was right.

Frida’s plans for the future were changed forever when a bus she was riding was hit by an out-of-control streetcar. Frida was impaled by an iron handrail through her abdomen. Somehow her clothes were removed by the collision, and a package of gold powder carried by a worker was scattered across her body. A man at the scene put his knee on her chest and pulled the rail out. Her spine and pelvis were both broken in three places, her right leg in eleven, her collarbone and ribs were broken, and her right foot was dislocated and crushed. The doctors didn’t think that she would survive. They had to put her back together in sections like a collage. She would be in and out of hospitals for the rest of her life.

Showing her extraordinary will to live, Frida was up and walking within three months but suffered a relapse within the year. It seems either the surgeons were negligent in not checking out her spine before discharging her or her parents hadn’t been able to afford certain procedures. Immobilized in a succession of plastic corsets, Frida decided to devote herself to painting. Her mother installed a four-poster bed in her room, with a mirror attached to the underside of the canopy, and had a special easel made up for her so that she could work while she recovered. Other than attending art classes in school, Frida had no formal training but she had developed a keen eye while working with her father, a photographer, who taught her how to use a camera and, later, how to develop and retouch photos. She began to study art books for hours on end, painting portraits of her sisters and friends, but her greatest Muse was herself. In two years, she had executed over a dozen paintings. What is remarkable is that Frida never painted the accident. Only a single pencil drawing, done in 1926, exists to record the life-changing moment. Years later Frida said that she had wanted to paint the accident, but couldn’t; it was too important to reduce to a single image.

The “other accident” occurred when Frida and Diego met again at a party given by a mutual friend, photographer Tina Modotti. Needing to know if she had the goods, Frida took her paintings to Diego to ask him if she had any talent. Soon they were embroiled in a passionate affair. “On a sudden impulse, I stooped to kiss her. As our lips touched, the light nearest us went off and came on again when our lips parted,” Diego later wrote. They kissed over and over under different street lamps with the same fascinating results. Diego was enchanted by Frida’s fiery personality, her quick, unconventional mind, and her cheekiness, but most of all by her talent.

Frida’s family wasn’t exactly thrilled with her new love. Although he may have been the most famous artist in Mexico, Diego was nobody’s idea of a Latin lover. He was forty-two, weighed over three hundred pounds, was a stranger to personal hygiene, and, more important, was married. But he was also full of humor, vitality, and charm, and he sincerely liked women. When Diego asked her father for permission to marry her, her father told him, “Don’t forget that my daughter is ill, and that she will be ill all her life. Think about it.” When they eventually married, her family bitterly described it as the union of “an elephant and a dove.” There were several unsettling incidents at the wedding that seemed to be an omen of things to come. Only her father showed up to the nuptials. At the reception, Diego’s ex-wife, Lupe Marin, turned up and insulted the bride, and Rivera got drunk, drew his pistol, and fired, breaking a man’s finger. Frida was so upset; she burst into tears and went home to her parents. She didn’t move in with Diego for several days.

From the beginning Frida worshipped Rivera, believing him to be a genius. She painted little during these years, content to be Mrs. Diego Rivera. She used to bring his lunch to him while he worked and even went so far as to befriend his former wife to pick up tips on how to please him. When Diego was expelled from the Communist Party, Frida quit, too, out of solidarity. Knowing his interest in the indigenous Mexican culture, she began to wear the Tehuana clothing that he liked; the ruffled and embroidered blouses, long skirts, and enough gold jewelry to make a rap star jealous became her signature look. For Diego, however, Frida came third in his life, after his art and himself.

Their life together was as much a work of art as their paintings. In the San Ángel district of Mexico City, they had a pair of houses built for them, connected by a walkway; Frida’s was sky blue, Diego’s bigger and bloodred. The houses expressed Diego’s idea of independence between a man and a woman. When Frida was angry, she would close the door on her side of the walkway, forcing Diego to have to go downstairs, cross the yard, and knock on her front door. Their home, filled with pets, became a mecca for the intelligentsia, with writers, artists, and photographers frequently visiting.

When Frida became pregnant she was ecstatic, although Diego was less excited. He was a crap father to the children he already had. After telling her that she would probably never be able to carry a child to term, doctors advised a medical abortion. Frida was devastated. During their marriage, she tried at least three more times to have a child, over Diego’s objections. The miscarriage she suffered when they were living in Detroit led to one of her most powerful and intensely personal paintings. With no children of her own, Frida lavished love on her nieces and nephews, as well as a menagerie of animals.

Another torment in Frida’s life was Diego’s infidelities. A doctor once told Diego that he was biologically incapable of being faithful, which he used as a justification for his rampant womanizing. Although Frida knew of his reputation before they married, no doubt she thought that her love would change him. She bore it stoically, even becoming friends with some of his lovers, but Diego’s affair with her sister Cristina finally crossed the line. In his autobiography, Diego wrote, “If I loved a woman, the more I loved her, the more I wanted to hurt her. Frida was only the most obvious victim of this disgusting trait.”

Frida expressed her feelings about the affair in A Few Little Pricks (1935), depicting a man who has stabbed a woman to death. While the man and woman resemble Diego and her sister, it is really Frida wielding the knife. Kahlo once said, “I paint myself because I am often alone and I am the subject I know best.” As a symbol of her new life, Frida cut her hair and stopped wearing the Tehuana clothing that Diego loved.

Her discovery of this affair freed her to assert herself both artistically and sexually. She moved out of their house and into a flat in town. From then on she began to have affairs, with both men and women, seeming to have lost all her inhibitions. Diego’s jealousy prevented her from flaunting her affairs in public. When Rivera found out about her affair with the sculptor Isamu Noguchi, he threatened to kill him. She also had an affair with Diego’s personal hero, Leon Trotsky, one of the leaders of the Russian Revolution. Kahlo nicknamed him El Viejo (Old Man) and found his vigorous, intellectual personality stimulating. On his birthday, she gave him a painting entitled Self-Portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky (1937). Frida didn’t take the affair seriously; it was just a way of getting back at Diego. Rivera suspected nothing of her affair with Trotsky for over a year. When he eventually found out, he broke all ties with his hero.

On the career front, these were some of her most prolific years. Diego encouraged Frida to show and sell her work, which led to the actor Edward G. Robinson purchasing four of her paintings. Her work expanded beyond the personal. Kahlo was influenced by ex-votos (religious paintings) of the previous century, Goya, pre-Columbian statues, Hieronymus Bosch, and Brueghel. She began to paint monkeys, which, though symbols of lust in Mexican mythology, she portrayed as gentle and caring. She created complex, visual symbols, using a primitive style of bright colors. Frida’s art is specific and so personal that it can hurt to look at the images. She bled elements of her life onto the canvas, as though she had opened a vein, tempered by humor and fantasy.

In 1938, an art gallery owner in New York offered her a one-woman show in which she was celebrated as an artist in her own right. She showed twenty-five works and half of them sold. She was now becoming financially independent of Diego although it was he who drew up the guest list for the private showing. Critics were enthusiastic and people began commissioning new work from her. André Breton, the leader of the surrealists, was struck by how similar her work was to the movement despite her never having seen a surrealist painting. He offered her a show in Paris as part of an exhibition called Mexique. And she had a new love in Nickolas Muray, a Hungarian photographer.

While Frida eventually became disillusioned with Breton, she enjoyed meeting other artists. She even inspired designer Elsa Schiaparelli, who was so taken with Frida’s Mexican attire that she created the Madame Rivera dress. When Frida returned to the States it was to discover that not only had Nickolas Muray fallen in love with someone else but that Diego was sleeping with her sister again. It was Diego’s idea to seek a divorce. As he put it, he wanted the freedom to sleep with any woman he chose without having to worry that he was hurting Frida. He also wanted Frida to have more independence, which she neither wanted nor needed. Divorced in the fall of 1939, Frida, instead of celebrating, began to drink heavily instead. She couldn’t live with Diego but she couldn’t live without him, either. “I drank to drown my pain but the damned pain learned how to swim!”

After a year, though, Diego urged her to remarry him and she finally agreed, but under two conditions: she wanted to be financially independent, and she would no longer sleep with him. They were remarried on Diego’s birthday in December 1940. Frida moved into Casa Azul, her childhood home, while Diego lived in a flat in San Ángel. Frida now mothered Diego; he was not only husband, friend, lover, but the child that she longed for but could never have, which was fine by Diego. Despite his inability to keep his pants zipped, Frida loved Diego and knew he loved her. A good friend said of the remarriage, “He gave her something solid to lean on.”

Frida started teaching at the School of Painting and Sculpture three days a week. Instead of just teaching about technique, she took her students on adventures to the market, to shantytowns, archeological sights, even to bars. She wanted to put them in touch with life. But Frida’s body was breaking down, and soon it became impossible for her to stand or sit. The treatments seemed to just make things worse. She had sandbags attached to her feet while being suspended in a vertical position, she had bone grafts, and she spent a year in a Mexico City hospital, but nothing worked. Some biographers speculate that the majority of her operations were unnecessary, that they were a way for Frida to get Diego’s attention. To keep up her spirits, Frida would treat her plaster corsets like works of art. In The Broken Column (1944), Frida’s nude body, encased in a medical corset pierced by nails, is cracked open to show a shattered column, as pale tears pour down her face. Her paintings became a vehicle for channeling and expressing her pain.

In 1953, her friend Lola Álvarez Bravo decided to arrange a one-woman show for Frida at the Galería de Arte Contemporáneo. Although doctors informed her that she was too ill to attend, Frida was not about to miss her moment. Diego arranged for her four-poster bed to be put up in the middle of the gallery. Frida arrived by ambulance like Cleopatra on her barge. She lay in the center, absorbing all the attention, exultant but racked with pain.

Frida fell into a deep depression when her right leg had to be amputated below the knee due to gangrene. She wrote in her diary that she knew the end was near. “I hope the exit is joyful . . . I hope never to come back.” She got her wish on the morning of July 13, 1954. It was a few days after her forty-seventh birthday.

While Diego Rivera was more famous during their lifetimes, the tide began to turn posthumously in the 1980s with the rise of neo-Mexicanism. Kahlo has become more prominent as feminists have taken her up as an icon. Fridamania has taken hold as her likeness now appears on everything from mouse pads to tea towels. In 2008, as part of the centennial celebration of her birth, a major exhibition of her work traveled across the United States. Kahlo’s legacy as one of the most important and original artists of the twentieth century is assured.