19

SATURDAY THE FIRST of August was bright and sunny, with a fresh enough breeze to dispel sloth if not despondency. To Charlotte, who craved a restoration of order and complacency in her life, it seemed important to do the little she could to bring that about in as brisk and business-like a manner as possible. She therefore took exaggerated care with her dress and appearance before leaving the house and stopped in Tunbridge Wells to buy a punctiliously listed assortment of domestic necessities before driving south-east towards Rye and a rather more demanding task she had decided to set herself.

Jackdaw Cottage was, as usual, clean and well-aired. Charlotte walked around it slowly, schooling herself to see it as a piece of property, not a repository of dreams and regrets. She was surprised by how successful she was, by how obedient her emotions were. There had to be a way of coming to terms with the discoveries she had made in the past week and she was determined to find it. So far, the only way she could imagine was to isolate herself from Maurice, from Beatrix’s memory and from every tangible reminder of their importance in her world. And so far, it seemed, so good.

From Jackdaw Cottage she went straight to an estate agent in the High Street, where she deposited a key and arranged for the house to be valued and put on the market as soon as possible. Then she called on the Mentiplys and told them what she had done. They were not surprised. Indeed, they had been expecting her to make such an announcement for some time. Charlotte was persuaded to stay for coffee and while Mrs Mentiply was in the kitchen preparing it she asked Mr Mentiply, in as casual a manner as she could contrive, to confirm his sighting of Spicer in Rye on 25 May.

‘It was him all right. Not a doubt of it. But how did you know I spotted him? I only told that brother of Fairfax-Vane. The Missus reckoned I shouldn’t have. Has he been bothering you?’

‘Not exactly.’

‘Making trouble? He seemed the type.’

‘I suppose you could say so. But don’t worry. I can handle the situation.’

Charlotte’s choice of phrase lodged in her mind and acquired a guilty resonance as the day progressed. After leaving Rye, she drove to Maidstone and located the street where she had been born and her parents had entered into their secret pact with Beatrix. The houses were more dilapidated than she remembered, the parked cars more numerous but less highly polished. Her birthplace had its sagging curtains drawn in the middle of a hot afternoon, with deafening rock music billowing from the only open window. For this she felt oddly grateful. Nostalgia and noise were mutually exclusive. And she had no use for nostalgia.

She returned to Tunbridge Wells just as the coolness of the evening was beginning to drain some of the heat from the day. She thought of what she had said to Mr Mentiply, of how true it was and yet how shameful. She thought of how intolerable it would be to continue, week after week, pretending Derek Fairfax and his imprisoned brother did not exist. And at that she surrendered to impulse.

He had written to her from his home address in Speldhurst, a well-to-do commuter village north-west of the town. Charlotte drove directly there and found Farriers, a cul-de-sac of widely spaced bungalows, without difficulty. But at number six there was no answer and she retreated, uncertain whether to be disappointed or not. A few minutes later, passing the pub in the centre of the village for the second time, she glanced into its garden and noticed a solitary figure sitting at one of the trellis tables. It was Derek Fairfax.

Charlotte overshot the entrance to the car park and had to reverse some distance up the lane to reach it. This manoeuvre, of which Fairfax had a clear view, seemed certain to attract his attention, but he failed to look up as she approached his table. He was casually dressed, doodling with a ball-point pen on a paper napkin whilst cradling his beer-glass against his cheek, completely absorbed, so it seemed, in his own thoughts.

‘Mr Fairfax?’

He started violently and, as his eyes flashed up to meet hers, she noticed him screw the napkin into a ball and drop it into the ashtray. ‘Miss Ladram, I didn’t … I’m sorry, I never …’ He frowned. ‘Were you looking for me?’

‘Yes. I’ve just called at your house.’

‘Really? Why?’

‘I’m not completely sure. I …’

‘Would you like a drink?’ He rose, smiling awkwardly.

‘Yes. Yes please. A gin and tonic.’

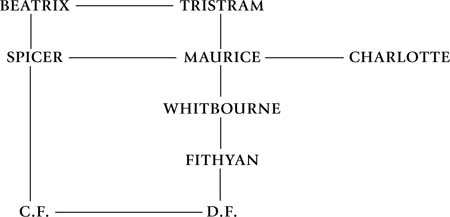

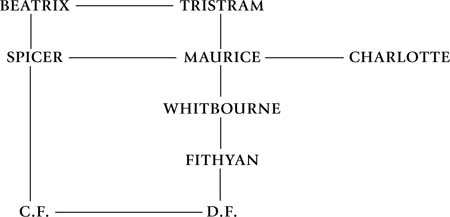

‘Sit down. I’ll go and get it.’ He drained his glass and set off with it across the garden. Charlotte sat down and watched him until he had vanished into the shadowy interior of the pub. Then, licking her lips nervously, she plucked the screwed up napkin from the ashtray and flattened it out on the table. A diagram confronted her, comprising names both familiar and unfamiliar, juxtaposed according to principles she could not immediately grasp.

She realized D.F. and C.F. must represent Derek and Colin Fairfax and knew Fithyan & Co. was the accountancy firm Derek worked for, but who Whitbourne might be she could not conjecture. As for her own position, marginal to the rest, no more, in one sense, than an adjunct to Maurice, she could not decide whether to feel relieved or insulted. Nor could she risk prolonged scrutiny of the diagram, for already Fairfax had reappeared in the pub doorway. She compressed the napkin in her hand and replaced it in the ashtray, then looked up to meet his gaze. She wanted to smile, to assure him that his preoccupations were hers as well. But, in the event, she merely thanked him for her drink in a cautious murmur.

‘So, why did you want to see me?’ He took a gulp at his beer as he sat down.

‘To … To ask if you’d done what you said you would.’

‘Tell my brother and his solicitor that I believe your brother was responsible for Beatrix Abberley’s death, you mean?’

‘Well … Yes.’

‘I told his solicitor. You’ll be glad to know he was unimpressed.’ He swallowed some more beer and Charlotte became aware of a vein of sarcasm in his remarks which alcohol could easily turn to bitterness.

‘What about your brother?’

‘I visited him today in Lewes Prison. In fact, I’ve just returned from there. The trip left me feeling in need of a drink. Of several drinks, come to that.’

‘It’s a depressing place, I imagine.’

‘Yes. It is. But it was worse today than usual.’

‘Why?’

‘Because I lied to him.’

‘You did what?’

‘I lied. He asked if I’d found anything out. And I said I hadn’t.’

‘Why did you do that?’

‘Why do you think?’ He set his glass down and leaned forward across the table. ‘Because there’s no evidence, Miss Ladram. Not a shred. I know what your brother’s done. And so do you. But I can’t prove it. I can’t even suggest it without …’

‘Without what?’

‘Never mind.’ He waved away a gnat and took another gulp of beer. This glass, too, would soon be empty. ‘Your brother’s in the clear. And so are you. What more do you need to know?’

‘Why do you say I’m in the clear?’

‘Because, without evidence of his guilt, you can pretend he’s innocent, can’t you? And benefit from his crime.’

‘Benefit? In what way?’

‘I assume some element of the royalties goes to you.’

‘You assume wrong.’ Charlotte felt herself flush. ‘My mother bequeathed all her royalty income to Maurice. As did Beatrix.’

‘Wonderful.’ He smiled humourlessly. ‘That salves your conscience very neatly, doesn’t it?’

‘It doesn’t need salving.’ But Charlotte knew otherwise. Fairfax was right. Indirectly, she was bound to benefit in some way. Perhaps she already had, for Maurice had never pressed her, as he reasonably might, either to sell Ockham House or to buy him out of his share of it. The sale of Jackdaw Cottage might solve that problem, of course, but it would not be Charlotte’s to sell if Beatrix were still alive. ‘What do you want me to do, Mr Fairfax? As you say, there’s no evidence to support your theory.’

‘What if there were?’

‘That would be—’ She broke off, reminding herself that Fairfax did not know – and must not know – why Maurice needed the royalties to continue. ‘But there isn’t,’ she said with stubborn finality. ‘And there can’t be, because Maurice didn’t do what you seem to think he did.’

‘You have to say that, of course. But you don’t believe it, do you?’ His eyes were fixed on her in open challenge.

‘I most certainly do.’ She glanced away, knowing what he would conclude from her inability to face him. ‘I think Emerson McKitrick stole the letters from Frank Griffith and destroyed them in order to protect his account of Tristram Abberley’s life. I’ve told Frank so. And now I’m telling you.’

‘How did Frank react?’

‘I didn’t—’ She forced herself to look back at him. ‘I haven’t spoken to him. I left a note at Hendre Gorfelen when I drove there yesterday. He wasn’t in.’

‘Couldn’t you have waited?’

‘I suppose so. But it’s a long—’

‘You didn’t want to wait, did you? You were glad he wasn’t there.’ He quaffed some more beer. ‘Perhaps you should have left me a note as well. It’s so much easier on paper, isn’t it? So much more … convenient.’

The truth of his words and the falseness of her own struck home at Charlotte. If she remained, she would either compound the lie she had told or confess to it and all she could be certain of was that she must do neither. ‘There’s nothing more to be said, is there?’ She stood up. ‘I think I’d better leave.’

‘So do I.’ Fairfax drained his glass and rose to confront her across the table, his glare crumpling suddenly into something forlorn and appealing. ‘I’m sorry if I’ve offended you. I realize you’re in an invidious position. But it’s a great deal better than my brother’s position, isn’t it?’

‘Yes. And—’ The look that passed between them in that instant carried with it a disturbing quality of self-recognition, as if each saw clearly their own frailties reflected in the other. ‘I’m sorry too. But sorrow doesn’t help, does it?’

‘Not a scrap.’

‘Goodbye, Mr Fairfax.’ She was tempted to offer him her hand, then decided that any suggestion of agreement between them – of unity of purpose – was best suppressed.

‘Goodbye, Miss Ladram.’

She turned and walked quickly away across the garden. When she reached her car and glanced back, she saw he was already heading towards the doorway of the pub, head bowed, empty glass suspended in his hand. They would not meet again. If they did so by chance, they would pretend not to know each other. This was the end both of them had feared from the moment Frank Griffith had agreed to share his secret. This was knowing the truth and knowing it could not be changed.