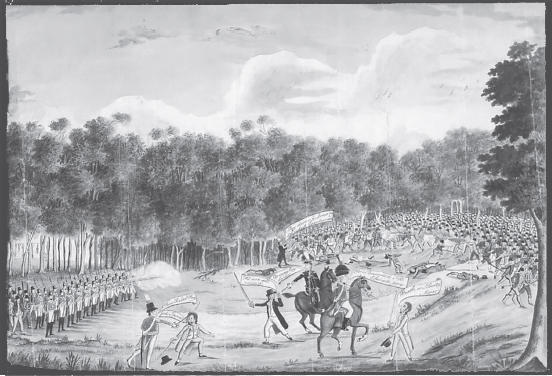

‘Battle of Vinegar Hill’, convict uprising at Castle Hill, Sydney. Inscription below image says, ‘Major Johnston with Quartermaster Laycock and twenty five privates of ye New South Wales Corps defeats two hundred and sixty six armed rebels, 5th March 1804.’

The waves were high upon the sea, the wind blew up in gales

I’d rather have drowned in misery than come to New South Wales

‘Jim Jones at Botany Bay’

Oh! if you had but seen the shocking sight of the poor creatures that came out in the three ships it would make your heart bleed; they were almost dead, very few could stand, and they were obliged to fling them as you would goods, and hoist them out of the ships, they were so feeble; and they died ten or twelve of a day when they first landed.

It was not only this unidentified convict woman who was appalled at the state of those who arrived aboard the Second Fleet in 1790. The Reverend Richard Johnson, chaplain to the settlement at Sydney Cove, was not prepared for what he saw—and smelled. Johnson went aboard the convict ships in the fleet to inspect the newcomers:

Was first on board the Surprise. Went down amongst the convicts, where I beheld a sight truly shocking to the feelings of humanity, a great number of them laying, some half and others nearly quite naked, without either bed or bedding, unable to turn or help themselves. Spoke to them as I passed along, but the smell was so offensive that I could scarcely bear it.

Johnson visited the Scarborough next but the captain talked him out of going below. The condition of the convicts aboard the Neptune was so bad that he did not even try to go below decks. But the end of the voyage was not the end of the dying: ‘Some of these unhappy people died after the ships came into the harbour, before they could be taken on shore—part of these had been thrown into the harbour, and their dead bodies cast upon the shore, and were seen laying naked upon the rocks.’

Johnson went straight to the governor with his sorry tale. He later described the scene in a letter:

In consequence of which immediate orders were sent on board that those who died on board should be carried to the opposite north shore and be buried. The landing of these people was truly affecting and shocking; great numbers were not able to walk, nor to move hand or foot; such were slung over the ship side in the same manner as they would sling a cask, a box, or anything of that nature. Upon their being brought up to the open air some fainted, some died upon deck, and others in the boat before they reached the shore. When come on shore, many were not able to walk, to stand, or to stir themselves in the least, hence some were led by others. Some creeped upon their hands and knees, and some were carried upon the backs of others.

Fortunately, a tent hospital arrived as part of the Second Fleet’s much-needed cargo. About a hundred tents were pitched with great haste, and in each of these tents there were about four sick people: ‘Here they lay in a most deplorable situation. At first they had nothing to lay upon but the damp ground, many scarcely a rag to cover them. Grass was got for them to lay upon, and a blanket given amongst four of them.’ Around five hundred convicts were in need of medical attention:

The misery I saw amongst them is inexpressible; many were not able to turn, or even to stir themselves, and in this situation were covered over almost with their own nastiness, their heads, bodies, cloths, blanket, all full of filth and lice. Scurvy was not the only nor the worst disease that prevailed amongst them (one man I visited this morning, I think I may safely say, had 10,000 lice upon his body and bed; some were exercised with violent fevers, and others with a no less violent purging and flux.

It turned out that most of the convicts had been shackled together below decks for days at a time, up to their waists in bilge water, and ‘many died with the chains upon them’. Most were not released until a few days before they reached harbour. The reverend did what he could, though his compassion was soon tempered by observation and experience of ‘the villany [sic] of these wretched people’.

Some would complain that they had no jackets, shirts, or trowsers, and begged that I would intercede for them. Some by this means have had two, three, four—nay, one man not less than six different slops given him, which he would take an opportunity to sell to some others, and then make the same complaints and entreaties. When any of them were near dying and had something given to them as bread of lillipie (flour and water boiled together), or any other necessaries, the person next to him or others would catch the bread, &c., out of his hand, and, with an oath, say that he was going to die, and therefore that it would be of no service to him. No sooner would the breath be out of any of their bodies than others would watch them and strip them entirely naked.

It was a case of survival of the fittest:

Instead of alleviating the distresses of each other, the weakest were sure to go to the wall. In the night-time, which at this time is very cold, and especially this would be felt in the tents, where they had nothing but grass to lay on and a blanket amongst four of them, he that was strongest of the four would take the whole blanket to himself and leave the rest quite naked.

At the time he wrote this letter, around July 1790, Johnson had buried eighty-four convicts, one child and one soldier. By August the death toll was more than a hundred, with ‘numbers yet sick, some likely to die, and others never to appearance will be fit for any employment’. He was still struggling to cope:

Never did I see such a scene of Misery in my days, in every sense truly wretched, naked, filthy, dirty, louzy, & many of them unable to stand, to creep, or even to stir hand or foot. Have been a great deal amongst them, till I have come home quite ill.

The reverend continued to do his duty, despite being unable to convince the governor to build a church and being assigned no convict to help him cultivate his garden or shoot his meat. His frequent representations and complaints led Major Grose, while acting as governor, to call him ‘a discontented and troublesome character’.

By the middle of 1794 Johnson was still unhappy with his lot but able to report:

The Colony at this time seems to be in a more prosperous flourishing state than I have yet seen it.—The supplies we have just received from England & other Places came very seasonably, & it is expected that from this time we shall be nearly able to grow grain to supply ourselves.—The corn (wheat) in general looks promising. We still, however, want livestock both for manure & Labour. The ground is cultivated by the hoe, which is not equal to plow.—The soil in some parts is good, but will soon wear out unless fallowed & manured. The Colony spreads in extent every year. A great number of those whose term of transportation has expired have turned settlers, some of who are doing well, better than many farmers in England.

The Reverend Richard Johnson eventually returned to England in September 1800, his duty done to God, man and woman.

The transport Hercules arrived in Dublin in September 1801. The Irish convicts taken aboard included rebels from the United Irishmen Rebellion of 1798. They sailed on 29 November, bound for Port Jackson via Rio de Janeiro, an uncomfortable seven-month voyage and, as it turned out, one that was lethal for some.

At around 2.30 p.m. on 29 December, as Captain Luckyn Betts and his officers took a meal, they heard screams from the women convicts. The captain and his men ran from the cabin to find the sentries of the New South Wales Corps overpowered by a group of convicts who were in possession of the quarterdeck. A shot was fired, bringing other sailors and soldiers to the scene. The next forty-five minutes were filled with firing, slashing and battering as the mutinous convicts were driven back below decks and the ship secured.

Thirteen convicts were dead. One of the surviving mutineers, James Tracey, informed the captain that a convict named Jeremiah Prendergass was to be the ringleader of a second attempt if the first mutiny failed. Prendergass, kneeling on the quarter-deck, loudly proclaimed his innocence but was shot dead on the spot by Captain Betts. For the rest of the voyage, all the convicts were locked down in filthy conditions, deprived of adequate food, water, ventilation and sanitation.

When the Hercules arrived, many convicts were ‘dreadfully emaciated’, as Governor King wrote to Lord Hobart. Including the fourteen killed in the mutiny, the Hercules lost forty-four convicts. The surviving convicts were too badly debilitated to ever be of much use to a frontier colony.

At the trial of the mutineers, Tracey, along with several others, appeared against their former comrades as witnesses for the Crown. Surprisingly, the defendants were found not guilty. Captain Luckyn Betts was also tried for the murder of Prendergass but found guilty of the lesser charge of manslaughter. He was ordered to pay the very large sum of 500 pounds to the colony’s orphan fund and held in jail until the money was paid.

The odd outcomes of this affair persisted. Not long after the trial, James Tracey took to the bush with John Lynch and others, some of whom were known rebels, including James Hughes. They robbed and assaulted the Hawkesbury Valley settler Samuel Phelps, taking a silver watch, jewellery, clothing and other items of value, including a land title. Except for Hughes, whose bones were found at the foot of the Blue Mountains three years later, they were arrested, tried and sentenced to hang at Castle Hill on 26 September 1803.

According to the Sydney Gazette, Tracey remained defiant to the end, in contrast to his condemned companion:

One of the unhappy men, Lynch, seemed sensibly affected at his situation; and with a fervor suited to his circumstances, attended to the exhortations of the Minister, acknowledging himself guilty of the offence he was about to expiate. Tracey, on the contrary, assumed an air of sullen hardihood, denied his being accessory to the fact of which he had been convicted, and reproached the penitent, whose deportment was contrasted to his own.

There were no elaborate gallows with a trapdoor drop. The condemned men were bound and stood in a cart with a noose around their necks:

Shortly before the cart was driven off, Lynch addressed the spectators in a becoming manner, and hoped that his melancholy fate would operate on the minds of others as a caution against falling into similar vices: but in this last voluntary effort of contrition he was interrupted by his unrelenting companion who harshly desired him not to gratify the spectators and shortly after they were both launched into Eternity!

The report of the execution revealed that Tracey had been the instigator and ringleader of the Hercules mutiny:

He was foremost in the insurrection on board the Hercules on her passage hither, and was the first who dared attempt to surprise the Officers; but receiving a wound through the arm instantly turned upon the wretched companions of his guilt and rashness; and in consequence of his informations many afterwards suffered exemplary punishments, and too late repented of a precipitancy whose object merited no better fate. His companions had formerly nick nam’d him ‘The key of the works’, by which appellation he was generally distinguished.

In what was then the usual style of newspaper accounts of executions, Tracey was described as ‘an abandoned unrepentant sinner’. The hope was expressed that a public execution would be a warning to others: ‘We ardently hope therefore, that the ignominious end of these sufferers, whose vices death alone could put a period to, will deter all others from imitating them.’

These were not empty moralising slogans. There was a deeply prejudiced fear of the Irish convicts throughout the colony. As well as the rebellions that led to many of them being transported, Irish convicts were involved in escapes, attacks and a violent rising. Their large number and the insurrectionary experience of many were deeply troubling to the shaky government of the colony, to other convicts and to the small but growing community of free settlers.

As early as 1798 Governor Hunter was writing to the Duke of Portland about ‘the problem of the Irish convicts’:

I have to inform your Grace that the Irish convicts are become so turbulent, so dissatisfied with their situation here, so extremely insolent, refractory, and troublesome, that, without the most rigid and severe treatment, it is impossible for us to receive any labour whatever from them. Your Grace will see the inconvenience which so large a proportion of that ignorant, obstinate and depraved set of transports occasion in this country by what I shall now state.

He went on to complain about escape attempts, delusions of a colony of white people ‘in some part of this country’ and ‘their natural vicious propensities’.

The government’s darkest nightmares were realised in March 1804 when the Irish and some other convicts did rise up at Castle Hill. The insurrection was brutally but efficiently put down by Major George Johnston and his ‘Rum Corps’ at a place later to be known as ‘Vinegar Hill’ (near Rouse Hill), named after an earlier rebel battle in County Wexford, Ireland. The convict rebels’ battle cry was ‘Liberty or Death’. None received liberty and more than thirty received death, either under the musketry of the soldiers or at the gallows. The rest were flogged and shipped to the Coal River (Newcastle).

That was not the end of the colony’s Irish troubles, which were an extension of British repression since Oliver Cromwell’s time and before. Many disaffected Irish convicts were prepared to operate, like Tracey, as ‘the key of the works’, not only in New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land but also during Western Australia’s later period of convict transportation.

In 1814 Governor Macquarie was horrified at the arrival of three transports in ‘a calamitous state of disease’. The emancipist William Redfern was working in the colony’s rudimentary hospital and was told by Macquarie to investigate the fever ships. Redfern’s eventual report revealed their tragic tales.

After picking up her human cargo from the hulks at Woolwich, Sheerness and Portsmouth, the General Hewett sailed for New South Wales in August 1813. Aboard were 300 convicts, seventy soldiers, fifteen women, eight children and more than a hundred sailors, as well as several passengers. Many convicts had been confined below decks for almost a month by this time.

While they were at sea, the prisoners were allowed on deck in rotation but were again confined whenever the ship was in port. After nine days below decks at Madeira, the first sign of disease appeared. By the time the ship reached Rio de Janeiro, illness ‘had increased to an alarming degree’, though Redfern found that some attempts had been made to cleanse and purify the foul conditions:

The decks were swept every morning, scraped and swabbed twice a week; they were sprinkled with vinegar weekly, until they made Rio Janeiro, when this was discontinued. The ship was also fumigated once a week for 6 weeks, but was afterwards much neglected. That three weeks previous to their arrival at Rio Janeiro, their bedding was thrown overboard in consequence of having been wetted; from the want of which the convicts, when they came into a cold climate, suffered exceedingly.

To make matters worse, the captain was profiteering from the supplies intended for the convicts’ rations, apparently purchasing them and then selling them to his charges at ‘shamefully enormous prices’. At least the convicts were now allowed on deck for the rest of the voyage, but ‘It was now, Alas!, too late. No care, no exertion, however it might lessen, could now remedy the evil’. By the time the General Hewett reached Port Jackson thirty-four convicts had died from dysentery and typhous fever. Many of the survivors had to be hospitalised.

The Three Bees sailed from Cork on 27 October 1813 with 219 Irish convicts aboard. They were allowed on deck but suffered from extreme cold in Rio de Janeiro where the first convict died of fever. Despite efforts to cleanse the ship, by the time she arrived and disembarked her cargo in May 1814, ‘55 were sent to the hospital in a dreadful state’. Nine convicts died during the voyage. (Not long afterwards, the Three Bees was destroyed when her store of gunpowder exploded near the present site of the Opera House.)

The third fever ship, the Surry, left England with 200 transports early in 1814:

On the 7th of March, John Stopgood sickened, the first that laboured under a well defined case of Typhus or common ship fever. On the 12th John Ransom died of fever, and another fatal termination of fever occurred on the 22nd May. No attempt appears to have been made towards ventilating the prison and neither the Surgeon’s representations nor his efforts met with that attention or assistance from the Captain and his officers, which it was their duty to have afforded him. On the 22nd of May, Isaac Giles died of fever, and on the 9th of June, Aaron Jackson died of fever, from which period the deaths became awfully frequent.

By July, so many officers were ill that the ship could not be manned. Fortunately, the transport Broxbornebury hove in sight and was hailed. When some of her sailors boarded the Surry, they found that ‘the Captain, two Mates, the Surgeon, 12 of the ships’ company, 16 convicts and 6 soldiers were lying dangerously ill with fever. Captain Paterson died the same day’.

They finally reached their destination with the assistance of crew from the Broxbornebury in late July:

The sick were landed and taken into tents prepared for their reception on the north side of Port Jackson. Every plan was adopted and carried into effect, that had a tendency to cut short the progress of contagion. The measures adopted proved so effectual, that but one case of infection took place after the sick were landed.

Of those aboard the Surry, casualties totalled thirty-six convicts, four soldiers and seven seamen, including the captain, both mates and the surgeon.

William Redfern’s report made recommendations on improving hygiene, nutrition, ventilation and fumigation, as well as allowing prisoners to access fresh air and sunlight. Macquarie agreed, reporting to Earl Bathurst back in England:

Out of those landed, it has been necessary to send fifty-five to the Hospital many of them being much affected with Scurvy and others labouring under various complaints. On enquiring into the cause of this mortality and sickness, it appeared that many of them had been embarked in a bad state of health, and not a few infirm from lameness and old age.

Together with Macquarie’s representations to the British government, Redfern’s report led to significant improvements in conditions aboard future transport ships. Scurvy and other diseases such as smallpox would still plague convict transports after the three fever ships of 1814, but if Redfern’s sound advice was followed they were more effectively minimised and contained.

Despite his abilities as a doctor and manager, Redfern would be refused promotion to the position of principal surgeon, largely because he was an ex-convict. He resigned and went on to establish a small farming empire in the colony and was a founding director of the Bank of New South Wales, becoming a leader in the efforts of the emancipists to assert their rights as free citizens. His wealth allowed him to continue to support the poor, including Aboriginal people. He is commemorated in the name of the Sydney suburb of Redfern.

The dangers of voyaging from Britain to the other side of the world in small ships were many. One transport experienced storm, sickness, a riotous crew and an attack by the United States of America.

The transport Francis and Eliza sailed from Cork, Ireland, in December 1814. She carried more than fifty male convicts and around seventy female convicts bound for New South Wales. Separated from the convoy in a storm off the island of Madeira a month later, she had the misfortune to meet with the American privateer, Warrior. Britain and the United States were at war again and American ships were given the legal right to harass and plunder British merchant ships. That included convict transports carrying armed soldiers.

The Warrior was a heavily gunned warship carrying more than one hundred and fifty armed soldiers and crew under the command of Captain Champlin. It did not take the Americans long to capture the lightly armed transport, defended with only four guns. Captain Harrison of the Francis and Eliza was taken aboard the Warrior and held for some hours while the Americans plundered his ship. According to a report in a colonial newspaper:

[The Francis and Eliza was] stripped of all her arms, rigging, provisions, medicines, charts, stores, and in short of everything necessary for pursuing her voyage to NSW. These marauders even plundered the Captain and passengers of their clothes. They then put on board the master and crew of the brig Hope, Robert Pringle, from Greenock to Buenos Ayres, and, after setting the convicts at liberty, and throwing their irons into the sea, left the Francis and Eliza to her fate. The scenes of horror that ensued, it would be impossible to describe. They were everything that depravity, desperation and inebriety could produce. The Captain’s life was repeatedly attempted, and conspiracies to scuttle and blow up the ship and to set her on fire, were happily discovered and frustrated.

The Americans also transferred aboard the crew of another ship they had previously captured. Harrison was returned unharmed to his ship but several crew members deserted, leaving the Francis and Eliza in a dangerous situation. The convicts were no longer confined and discipline among the crew and soldiers evaporated:

The Crew almost a score in number seized upon the spirits and other liquors, which were treated as common plunder, and the most dreadful scenes of riot and intemperance prevailed, until their arrival at Santa Cruz, five days later. But for the steady conduct of the Male Convicts, it is certain that the Females on board would have received the unwelcome and lewd attentions of the debauched seamen, who on several occasions set the Ship on fire during their drunken frolics.

According to one account of this incident:

One of the female prisoners, distinguished for her personal charms, passed herself off to the captain as the well known Mrs. M.A. Clarke. Her attractions conquered the heart of the American, who implicitly believing the story she told of having been convicted upon a false charge of swindling, he took her on board, presented her with 2000 dollars in cash, besides linen, clothes, &c.; nor did he discover the imposture until he returned to port, when the lady eloped from him with a sailor, and shortly after sued him for the payment of a promissory note for 5000 dollars, which he had unthinkingly assigned her.

The ‘well known’ Mrs M.A. Clarke was the mistress of Frederick, Duke of York.

At Santa Cruz, the commander of the British sloop Harrier received a letter from Captain Harrison detailing his troubles and requesting him to bring his men aboard and help him restore order:

[The commander] immediately boarded the vessel with three of his officers, and a party of marines, when he found the ship in the full possession of the convicts, and every thing in the greatest disorder and confusion; that upon the representation of the master of the violent and disorderly conduct of the chief mate and four of the seamen…removed the said five persons from the said ship to his own sloop, and ordered a court-martial upon such of the soldiers as had been most guilty of mutinous and unsoldierlike conduct, and which court-martial awarded a severe punishment, which they accordingly underwent.

The broken bulkheads of the convict prison below were restored and the convicts returned to their confinement. From Tenerife, the Francis and Eliza received a naval escort and at Senegal a military guard of the Royal African Corps. In convoy, the transport proceeded to Sydney via the Cape of Good Hope, arriving in early August 1815. Here, the extent of the captain’s and other losses was revealed:

His private losses are very severe indeed, as are those of Mr. West, ship’s Surgeon, from whom an investment of a thousand pounds was wholly taken, together with most of his wearing apparel, surgical instruments, and the ship’s medicine chest, which latter loss, but for the favour of Providence, might have been followed by the most fatal consequences to the numerous persons on board.

Not surprisingly, this incident was greeted with outrage by the British:

The case of the convict ship Francis and Eliza affords a new proof of the total disregard in which the Americans hold the rights and usages of civilized nations, while in a state of hostility with one another. Their conduct towards the above mentioned vessel would disgrace a Barbary corsair, and violates every principle of international faith, generosity, and forbearance which their magnanimous President so clamorously affects to advocate.

But the American version of events was very different:

Captain Champlin assures us, that so far from releasing the convicts, (as there stated) he found them in a state of mutiny and insurrection, and supplied the captain with a guard to suppress it. He also put a crew on board of her, (of British prisoners he had captured) which made her number of seamen superior to that of the convicts. No plunder, whatever, was permitted, and she was left with a bountiful supply of everything, proper for a three months’ voyage, with Madeira only 50 miles to leeward, where any succors could have been procured.

While claim and counterclaim echoed across the Atlantic and the Pacific, justice still had to be served. Around eight people died of sickness during the fraught passage of the Francis and Eliza and others needed medical attention when they arrived. The male convicts were taken to work at the settlements of Windsor and Liverpool and many of the women went to the Parramatta Female Factory.

The Francis and Eliza was the last ship to transport both men and women to Australia.

We did give them all a dinner that they could not swallow. Four and six dozen lashes to every man on Saturday; our sailors had no mercy in flogging them. We have all the ringleader[s] on deck chained down, several have since confessed the affair.

So an unidentified sailor described the aftermath of a murky series of events aboard the transport Chapman in 1817. The official story was that the mostly Irish convicts aboard plotted and prepared a mutiny even before they boarded the ship taking them to Port Jackson. Each prisoner took an oath, willingly or not, ‘to be true and loyal, and not to deceive each other’. Any who refused were ‘To be stiffled with blankets, quartered, and hove out of the port-holes’. The plan was to murder the sailors, soldiers and officers, sparing the first mate and a few sailors who had assisted the convicts in their design.

According to evidence given by convict Michael Collins, there was a secret password and, at the appointed time:

One part of the convicts to force the fore-scuttle, with a view of drawing the attention of every one on deck to that part; while the main body was to rush aft and force their way into the guardroom, for the purpose of getting possession of the arms, and go to the powder magazine, which they intended to set on fire, if they could not make their way back to the deck, as it would be as well to be blown up, as shot by the guard.

This was to be coordinated with another manoeuvre on deck:

There were 17 men allowed to wash on deck, who were selected out of the convicts for that purpose, all the stoutest men, besides three cooks and four swabbers, altogether 24; they were to watch the opportunity when the ship’s company went down to dinner, when the sentinels were to be knocked down, and their arms taken, and then come aft, and take possession of the quarter-deck, and cut every body down that attempted to come from below.

When the plot had succeeded they planned ‘a grand dinner; the dinner was to be roasted turkey, roast pigs, geese, with a glass of brandy; after the goose, Port and Madeira wine’. Then the convicts would sail their prize to America and freedom. If they were unable to sail for America, they would revert to the ship’s original course and sail to Australia where, according to one of the ringleaders, ‘sworn on their arrival at Botany, with the PILOT’S people, and as many as they could get there, to join them, to take Botany Bay’.

The Pilot was another transport crammed with Irish convicts travelling with the Chapman. In this version of the story, the plotters aboard both ships planned to join together when they landed and take over the colony. An unidentified sailor aboard the Chapman gave his account of what happened when the convicts launched their plot just a few days into the voyage:

On Thursday evening they made their attempt forward, first by forcing up the fore scuttle; finding they could not succeed, they all made a rush to force the aft hold bulk head, we then began to fire at all the hatchways, they still persisted, and sung out that they wanted no quarter; we kept firing until we found them all quiet, singing out for mercy. I went down with a party of the Guard, and demanded the dead and wounded. We found nine dead, and twenty-four wounded, who have since died of their wounds.

But that was not the end of the affair. Three days later, on Sunday evening:

We heard them consulting in a body below, the sentry fired, we then commenced for a little time until we found them all quiet. Killed one wounded six. We have not got half of them to the chain-cable, so there is no fear of their doing any more harm; if they do, we do not intend to leave a man of them alive. It was planned in Dublin prison, that whatever ship they embarked in, they would take and murder all hands.

This sailor, who would presumably have been a victim if the mutiny succeeded, was looking forward ‘to see them all hung at Botany Bay’.

After severe floggings, most of the convicts were chained up for the rest of the long voyage. One man, William Lea, was tied to a rope then thrown astern and towed along by the Chapman. Later he was chained to the poop deck for fourteen weeks. Others were whipped and severely treated.

The Chapman reached her planned destination with 186 of the original convict complement of 198. Seven had been shot dead, two died of dysentery and nobody seemed to know what happened to the remaining three. Suspicions were raised but an official inquiry concluded that the officers, crew and soldiers were guilty only of a misdemeanour. Governor Macquarie was not satisfied with this and sent the ship’s surgeon and three soldiers back to England, under guard, to answer to murder charges. Eventually the master, some officers and several soldiers of the Chapman went to trial at the Old Bailey in January 1819. They were all acquitted. The jury decided that the defendants’ fear of the convicts excused the killings, even if these concerns were unjustified.

This peculiar verdict has always left open the question of whether there actually was a mutiny aboard the Chapman. Or were the officers, crew and soldiers so fearful of the rumours that they attacked their charges before anything happened—or might have happened? There were accusations that two prisoners had given false information to the captain and doctor, fuelling their fears. In this interpretation, all the elaborate details of plots, oaths and passwords were merely invented to justify what might have been a massacre of defenseless men.

Few people have ever been quite sure what really happened aboard the George III in the D’Entrecasteaux Channel between the southeast mainland of Tasmania and Bruny Island in April 1835. She left London’s Woolwich Pier on 14 December 1834 with more than three hundred souls—crew, guards, convicts and free. By the time she reached Van Diemen’s Land fifteen men, women and children were dead. This was not an unusual death rate for convict ships at the time. But the figure was about to rise dramatically.

In bright moonshine on the night of 12 April, the George III hit an uncharted rock while taking a shortcut through the channel to Hobart. Almost immediately the decks were awash. The main mast and mizzen top-mast soon fell, entangling the deck in rigging and sweeping away one of the ship’s boats. Two remaining boats picked up those still clinging to the upper deck and thirty-six survivors were safely put ashore. The captain with five men returned to the wreck to rescue those still aboard, including the convicts.

The convicts were locked down below on the prison deck, and according to the Hobart Town Courier, they were ‘screaming in a most violent and agitated manner to be let out—they put their hands through the grating and seized the surgeon by the hands, saying “You promised to stand by us”.’ The ship’s surgeon, Dr Wyse, had promised to stay with the panicking convicts. As the waves battered the ship, the barricade erected to keep the convicts secure began to give way. Trying to save themselves, men began testing the barrier.

But then an order was given: ‘A considerable body of the military formed a compact guard round the hatchway with their muskets levelled in intimidation. It was at this period, that the sentries over the main hatchway, in obedience to the positive orders they had received, to keep the men below, fired.’ At least one convict was killed. ‘By this action the prisoners remained subdued, but they kept crying out that the water was gaining on them, and the crashing of the rocks through the ship’s bottom, was dreadful to hear.’

The justification for this extraordinary act was that the convicts would have overcrowded the ship’s longboat then taking off those above. According to the official account, as soon as the boat was safely away, the convicts were released to save themselves as best they could. Close to sixty were disabled with scurvy in the ship’s hospital and all of them drowned except for two lucky men. Of those convicts who made it to the chaos of the upper deck, thirty or more, including twenty boys, were washed to their deaths or died from exposure as they shivered through the long, cold night awaiting rescue.

When the rescue ships arrived from Hobart: ‘The scene of desolation was appalling. The waves had made a complete passage through and through the vessel—the masts overboard—the sides and bottoms gone—and the decks and other parts that still hung together floating up and down with the waves—while the anchors were resting on the rocks.’

There was nothing aboard but the body of an old lag on his third transportation. John Roberts, unable to swim, lashed himself to a ring bolt in the surgeon’s deck cabin, hoping he might be floated to shore if that part of the ship broke away.

In the end, more than 130 lives were lost from the wreck of the George III. Eighty-one convicts survived. A board of inquiry was held. Convict James Elliott testified: ‘I was in the hatchway several minutes before I could get up. The soldiers kept me down and threatened to fire; I heard two shots fired: the first shot killed Robert Luker, and about three or four minutes after another shot was fired and I saw another man fall.’

The inquiry nevertheless concluded that, ‘The conduct of all was most praiseworthy and entirely free from blame of any description’.

But then there were reports of bodies washed up bearing evidence of gunshots and sword cuts, leading to the exhumation of seventeen of the dead. The coroner decided that the wounds were the result of the bodies being washed against the rocks.

Among convicts and in the free community there were dark rumours. A poem appeared, said to have been written by a convict survivor of the tragedy:

A dreadful wreck we did sustain,

Near Derwent River’s mouth;

On a reef of rock we there did strike—

The wind being then due south.

The dreadful sufferings to relate

Would take a scholar’s skill,

To see us in the hold secured—

The water rushing in;

A guard was round the hatchway plac’d,

To shoot us if we mov’d,

When death was making rapid strides,

’Mong some of those we lov’d…

The belief that many more of the prisoners were shot grew with each telling, rolling down the years until it became accepted fact. Passed on to the descendants of convicts, the legend lived on and is still echoed in the local folklore of the region. A monument to the disaster was erected near the site in 1839. The inscription reads:

Near this place are interred the remains of many of the sufferers who perished in the wreck of George the III, convict ship, which vessel struck on a sunken rock near the Actaeon Reef on the night of the 12th April, 1835: upon which melancholy occasion 134 human beings were drowned.

This tomb is erected by the desire of His Excellency Colonel George Arthur, Lieut. Governor, to mark that sad event, and is placed on this spot by Major Thomas Ryan, 50th Regiment, one of the survivors of the occasion.

At 5 p.m. on 13 May 1835 the lookout aboard the barque Neva, a convict ship travelling through Bass Strait on its way to Melbourne, sighted a reef dead ahead. The master ordered evasive action:

The ship came head to the wind, and while in stays, struck and carried away her rudder—the wheel fell on deck, and the vessel being unmanageable, payed off before the wind. In a few minutes she took a reef on her larboard bow, and struck violently. A sea hove her broadside on, and bilged her—the next that followed, made a fair breach over her, and swept many of the unfortunate women overboard.

The 150 convict women on the stricken ship were being transported to New South Wales from Cork. They left Ireland in January with twenty-six crewmen, nine free women and fifty-six children. After a long voyage via St Pauls Island rather than the usual Cape of Good Hope, the transport was quickly breaking up on a reef off King Island in Bass Strait, trying to take the dangerous shortcut to Melbourne known as ‘threading the needle’. There was panic as passengers, crew and convicts rushed the only two boats and two rafts:

The pinnace was hove out, and the Captain, Surgeon, and several women got in, but before she could be shoved clear of the wreck, so many women rushed into her, that she sank alongside. The Captain and two others recovered the wreck. The long boat was then launched, into which most of the crew consigned themselves, but she had scarcely cleared the wreck, when a sea capsized her, and the whole number excepting the Captain and Chief Mate, met with a watery grave.

The two sailors managed to get back onto their vessel but she was disintegrating:

She soon after separated in four parts, the deck leaving her top, and dividing formed two rafts. On one of these the Captain and several of the surviving women held fast; the first officer, with some others, clung to the other. They floated clear of the wreck, and the hapless people, after clinging to them for 8 hours, were drifted upon them into a sandy bay.

The raft upon which was the first officer, being disengaged from the rigging and gear, went well in shore, and most of the people were saved from it. Those upon the Captain’s raft were not so fortunate—a large portion of the vessel’s foremast stuck through it, and occasioned it to ground, when about ¾ of a mile from it. A tremendous surf rolled upon the beach, which brake upon the raft, and swept from it every individual—the Captain, a seaman, and a woman gained the shore, the rest of this ill-fated little band, perished in the surf. Twenty-two persons in the whole reached the shore alive—seven of whom died the next day, either from over exertion, or injuries received in the melancholy struggle for life.

Only fifteen men and women were saved. They were lucky. They erected a tent from the remains of masts and sails washed ashore, along with few provisions. Living mainly on shellfish, they were found by the survivors of an earlier wreck on the other side of the island. This group had some hunting dogs and they were able to supplement the shellfish with wallaby.

On 15 July, most of the survivors of both wrecks were taken off the island by the owner of the Tartar. But three people searching for food on the other side of the island were left behind, two seamen and a convict woman named Margaret Drury. They were later taken off by a government boat and brought safely to Launceston Gaol, while officials decided whether the surviving convict women should stay in Van Diemen’s Land or go on to their original destination.

Margaret Drury was still in Launceston Gaol in late November when she was charged with drunkenness. The authorities eventually decided that the surviving women of the Neva should serve out their time in Van Diemen’s Land. In the meantime, romance had bloomed. Peter Robinson, one of the sailors left behind with Margaret on the island, applied for permission to marry her. They wed in January 1836 and, as usual with such marriages, the convict was assigned to her husband. But it did not go well.

A couple of months after the wedding, Margaret spent three weeks on bread and water for harbouring a convict woman who may have been trying to escape. The next February her husband brought a charge against her of drunkenness and indecent exposure. She spent six months in the Crime class, comprised of the most badly behaved convicts. After her release Margaret seems to have separated from Peter and lived on an island in Bass Strait. In July 1839 she received another six months for re-offending. During this sentence she again spent thirty days on bread and water in solitary confinement for disobeying orders. Despite her infractions, Margaret was freed in 1840 and settled back down with her husband. They had at least one child and later moved to Victoria.

It is thought that 224 people died in the wreck of the Neva, mostly female convicts and all the children. It is considered Tasmania’s worst shipwreck and one of Australia’s greatest maritime tragedies. Skeletons are still being found in the island. Seven turned up in 2010, inspiring Hobart psychologist Catherine Stringer to research the story and to create a unique memorial to the women and girls who died. She collected seaweed from the area, made it into paper and used that to fashion small dresses. The forty-two framed items in the collection are known as ‘The Neva Reliquary’.

Other artists and writers have been drawn to the tragedy, their researches raising doubts about the official accounts. There are anomalies in the evidence given to the inquiry and it has been suggested that, with a large cargo of rum, some of the women and the crew were drunk when the Neva struck whichever obstruction destroyed her. There is also a possibility that some of the cargo was not lost, as stated, but salvaged and later sold. We will never know if these rumours were true and although the Neva story is still not widely known today, it has generated some folklore, including the suggestion that she was carrying 50,000 pounds in wages for the soldiers guarding convicts in Van Diemen’s Land.