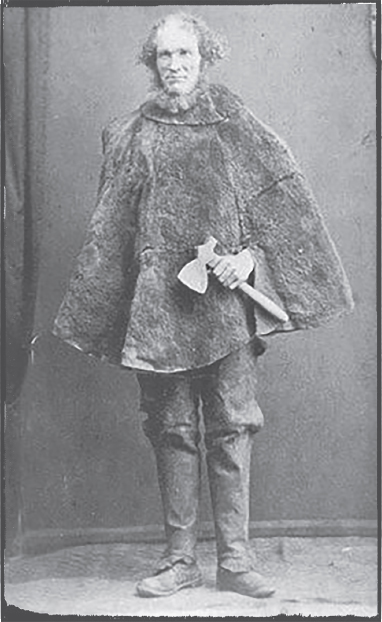

Moondyne Joe, (Joseph Bolitho Johns). This is the only known photograph of him, taken by Alfred Chopin. He stands holding a tomahawk and wearing a kangaroo skin cape. He was famous for the many times he escaped prison.

Will there no gleam of sunshine

cast o’er my path its light?

Will there no star of hope rise

Out of this gloom of night?

John Boyle O’Reilly

It was an unusual case at London’s Old Bailey court in July 1792. A woman and four men were on trial for escaping from New South Wales the previous year. Their bid for freedom was desperate and harrowing.

On the night of 28 March 1791 Mary Bryant (née Broad), her husband William and their children Charlotte and Emanuel stole the governor’s leaky cutter. With seven other men, they rowed through Sydney Harbour, turning north when they cleared the Heads. Their voyage would take them through unknown waters and past dangerous coasts back to the land from which they had been transported. Most would not survive their epic ordeal.

After two days sailing, the escapees went ashore and camped by a creek. They were visited by the local Aboriginal people who were friendly and happy to accept the clothing and other items the convicts offered. Some days later they needed to repair the cutter and landed in ‘a very fine harbor’. But this time contact with the ‘Natives’ did not go well. They were menaced by ‘great numbers armed with Spears and Shields’. Forming themselves into two groups, the fugitives firstly tried to ‘pacify them by signes, but they took not the least notice’. Then they fired a musket, but this had no effect and the fugitives were forced to make a rapid retreat to the sea.

They were by now running out of food and feeling the effects of exposure and heavy storms. One of the convicts kept a journal of the voyage in which he wrote: ‘the Woman and the two little babies were in a bad Condition every thing being so wet that we could by no means light a fire we had nothing to eat except a little raw Rice at night.’

After weeks at sea, the battered little boat was in the tropical waters of the Great Barrier Reef. Fish and turtle were plentiful and there was rainwater to drink. In the Gulf of Carpentaria they were attacked, probably by Torres Strait Islanders, and were later chased into the gulf by islanders in sailing canoes. They made a fast passage to Arnhem Land and from there reached Timor on 5 June 1791 after sixty-nine days at sea across 5000 kilometres of angry ocean and mostly hostile shores.

On Timor they were well received by the Dutch governor and looked after as shipwreck survivors. But after a few months there was some kind of falling out in the group, leading to the revelation that they were in fact escapees. They were jailed and after a few months taken in chains to the Dutch headquarters of Batavia, modern Jakarta. Batavia was notorious for fevers and here Mary Bryant’s son Emanuel died, not yet two years of age. Three weeks later his father died, leaving the dwindling group without a leader.

Three more of the men died while the fugitives were being transferred in separate ships to Cape Town. In April 1792, Mary and Charlotte Bryant, together with the surviving men, were shipped aboard the Gorgon bound for England. Despite their trials and recapture, they were pleased to be alive. But the heat of the tropics began to take its toll on the Gorgon. Some children of the soldiers aboard died and on May 6 Charlotte Bryant followed them. Mary was now the only survivor of her family and facing a death sentence.

The Gorgon docked in June and the escapees were taken to Newgate Prison to await trial. News of their escape and tribulations was now public knowledge and stimulated widespread sympathy. Instead of a death sentence, Mary Bryant and her fellow survivors were only required to finish out their original sentences. For Mary that meant release in May 1793.

The biographer and lawyer James Boswell interested himself in the case. Mary lodged with him in London after her release and before returning to her native Cornwall, though, according to Boswell, ‘her spirits were low; she was sorry to leave me; she was sure her relations would not treat her well’. Boswell organised a subscription fund to give Mary a pension, though it seems not to have been very well supported and it is likely that he personally paid her what was then a substantial sum of money. Shortly before his death in 1795, Boswell instructed his financial agents to: ‘put into the Banking Shop of Mr Devaynes & Co five pounds from me to the account of the Rev. Mr. Baron at Lestwithiel, Cornwall, and write to him that you have done so. He takes charge of paying the gratuity to Mary Broad.’

That generosity must have been very useful for Mary back home in Cornwall, especially if she was out of favour with her family, locally reputed to be sheep stealers. And she was grateful. In 1930 some documents were discovered in what had been Boswell’s Irish estate. With the papers was a package of ‘Botany Bay tea leaves’, or sarsaparilla, which Mary had evidently sent her benefactor. She must have taken a store of the leaves for drinking and remedy for scurvy on the escape boat. A couple of the leaves are held by the State Library of New South Wales.

It would only take them a week or so. Everyone knew that China lay to the north of New South Wales. A well-supplied group of determined convicts could easily walk to freedom. In 1791 twenty men and women tried it. Seven died and the lucky survivors were found almost naked and near death. They were brought back to Sydney and when they recovered from their ordeal, flogged.

This sorry tale did not deter others from attempting the same hopeless journey. In the following year alone, another forty-four men and nine women were reported to have disappeared into the bush on their way to China. The myth was a powerful one that no amount of actual experience seemed to quell. Six years later a group of Irishmen on the road to China via the Georges River were accidentally discovered and saved from certain death by local settlers. They were lucky.

In 1803 James Hughes, a tall Irish rebel, and fifteen others absconded from Castle Hill, a settlement northwest of Sydney. Robbing settlers as they went, all but Hughes were recaptured, thirteen being sentenced to death. Three years later an Aboriginal told a settler that the bones of a white man were lying with a musket and tin kettle (a billy) beneath the first ridge of the mountains. The settler accompanied the Aboriginal man to the spot and found a long-boned skeleton, presumed to be that of Hughes.

Another belief that gained currency with the convicts came from misinterpreting information gained from Aboriginal people. They told stories of a mysterious colony of white people said to be living several hundred miles to the southwest. As early as January 1788 a group of Irish transports went off in search of the other colony. They were pursued by soldiers and sixteen were taken back to Sydney and punished. This myth would not die either and continued to inspire escape plots, including a mass breakout from the government’s Toongabbie farm. Something had to be done. It was, and it involved an extraordinary convict named John Wilson.

Wilson was from Lancashire, where he had been arrested, tried and found guilty of stealing some cloth. He arrived with the First Fleet aboard Alexander. At the end of his seven-year sentence, he went bush and lived with the Darug people of the Hawkesbury River area. Together with a runaway convict, Wilson was arrested for attempting to kidnap several young Aboriginal girls. He managed to escape and returned to the Darug, taking a full part in their customs, battles and travels. He worked out how to communicate in a type of pidgin and may even have been initiated, bearing the scars that signified the making of an Aboriginal man. He was also known by his Aboriginal name of Bunboe (pronounced ‘Bunbowee’).

It was thought that Wilson was among the raiding parties associated with Pemulwuy, the Aboriginal warrior who led a fierce resistance to colonisation. In 1797 Wilson and three others were arrested and charged as ‘incorrigibles, rogues and vagabonds wandering at large’. Sentenced to seven years retransportation, he escaped and was outlawed in May. Being legally outlawed meant he must surrender or be shot on sight. Wilson returned to the settlement dressed in kangaroo skins, Aboriginal style. The colonists found the wild white man’s accounts of his adventures difficult to credit. But his wanderings had taken him well into the Blue Mountains and likely beyond them, where he had seen many things, possibly including the first sightings of wombats, lyre birds and koalas. He claimed to have also seen the bones of more than fifty convicts who perished in their vain attempts to reach China.

To David Collins, deputy judge advocate, Wilson was ‘a wild, idle young man who preferred living among the natives to earning the wages of honest industry’. Despite these criticisms, the ‘vagabond of the woods’ was known to have a unique knowledge of the country for miles around the settlement. This made him useful to the governor who employed him as a guide for exploring parties. Wilson was with a surveying and exploration party to Port Stephens under Charles Grimes in 1795. He saved Grimes’s life by wounding an Aboriginal man attempting to spear him. After his surrender, Wilson promised to reform and in 1798 Governor Hunter sent him with a group of convicts and guards into the bush to search for the rumoured lost colony. When the group failed to find the settlement, the governor hoped that the belief would die out and convicts would stop trying to escape. The party was also accompanied by one of Hunter’s servants, John Price, a young man at home in the bush and keen to explore further.

The eleven-strong group set off to cheers of encouragement. It was a very hot summer and at first, the going was thankfully easy through known country but they soon moved into rougher unknown territory. Most of the convicts soon tired of the tough going by the time they reached the present-day Picton area and returned with the soldiers to the settlement. But Wilson and Price pushed on with one of the more determined convicts. They reached a point more than 160 kilometres south of Parramatta where their rations ran out.

Their return journey was almost fatal. They were reduced to eating roots and grubs, tearing up their clothes to provide protection for their feet after their boots disintegrated. The exhausted men were saved only through Wilson’s bush craft. Price wrote: ‘I thought that we must all have perished with hunger, which certainly would have been the case had it not been for the indefatigable zeal of Wilson to supply us with as much as would support life.’

The governor was pleased with the results of the expedition. They found no mysterious white settlement and also discovered what seemed to be a hill of salt, a valuable commodity for the still struggling colony. Hunter again sent Price and Wilson south to confirm the salt discovery. Once again the leader and most of the group quit, leaving Price and Wilson to forge ahead. This time they got as far as modern-day Goulburn, further than any other known European.

Price and Wilson battled back, again surviving through Wilson’s bush skills. Soon after returning from the second expedition, Wilson went bush once again to a life which had taken him far past the limits of settlement and given him a knowledge of the country unmatched by any European. John Wilson’s vagabond life came to an end in 1800 when he was speared to death during his attempt to kidnap an Aboriginal woman.

The official description of the woman said to be Australia’s first female pirate is not flattering: ‘Charlotte Badger, a convict; very corpulent, with full face, thick lips, and light hair; has an infant child.’ And she had a very bad temper. Various writers have tried over the years to turn chubby Charlotte into a romantic lady buccaneer, dressed as a swashbuckler and brandishing a brace of pistols. But the reality is both more prosaic and more intriguing.

Charlotte arrived in the colony in 1801 with a seven-year sentence to serve for thieving. She became pregnant to a soldier and gave birth to a daughter, Anny. Nothing very unusual. But what happened next has become an enduring mystery spanning Australia, New Zealand, the South Pacific and possibly South America.

In 1806, Charlotte and Anny were aboard the 45-ton brig Venus on their way to Van Diemen’s Land along with several other convicts and a small crew commanded by Samuel Chace. Bad weather kept the Venus at Twofold Bay for more than a month, plenty of time for Charlotte and the other convict woman aboard, Kitty Hegarty, to get to know the sailors and male convicts. At some point Chace had to go ashore for business, leaving the first mate Ben Kelly in command. When Chace returned he found a party in full swing.

From this point in the tale, details vary. According to some accounts, Chace ordered the two convict women whipped but the crew refused, so he did the job himself. He then had the carousers chained up and told Kelly he would be dismissed as soon as the Venus landed. But the captain was forced to release Kelly when he sobered up as he was needed to navigate the ship.

When the Venus made landfall in the Tamar Estuary in June 1806, Chace went ashore with the official despatches he carried, again leaving Kelly in command. The captain unwisely spent the night visiting another moored ship, returning next morning to see his ship heading out to sea. Kelly and some of those aboard, together with Charlotte and Kitty, had mutinied. They forced the rest of the crew ashore at the point of swords and pistols.

The Venus was carrying a full cargo of stores and so was well prepared for a lengthy voyage as a pirate ship. But where did she go? Nothing was heard for nine months. Then an American whaler reported Kelly and another male mutineer living with Charlotte and Anny in the Bay of Islands, New Zealand. Kitty was dead and the Venus was under the command of another crew who were busy pillaging the Maori tribes along the coast. Eventually the Maori killed the crew and burned the Venus.

Charlotte and her companions lived in the Bay of Islands alongside the local Maori for eight years or so, until a British ship arrived and captured the two men. Ben Kelly was taken back to England, tried and hanged for piracy. Charlotte is said to have escaped with Anny and—again, accounts vary—either to have remained there, living with a Maori warrior, or to somehow have made her way to Tonga. She either remained there until her death or, in yet another version, formed a liaison with the captain of an American whaler and disappeared into history.

Nobody is sure what happened to Charlotte Badger the pirate and her daughter, Anny. Perhaps yellowing documents will turn up one day with some hard evidence. A Chilean professor is said to have uncovered some new sources in the 1950s that provide an elaborate counter-version of Ben Kelly’s survival and subsequent adventures in South America, but this remains unverified.

In New Zealand, though, Charlotte Badger is remembered as the first female Pakeha, or European woman, to settle there. She probably was not the first, but this is just one more element of the quicksilver legends about Australia’s first female pirate.

Cannibalism among escaping convicts was not common but it happened. The case of Alexander Pearce is probably the best known.

This group continued their pointless wandering through the bush. Another was killed and eaten, and another died of snake bite and was eaten, leaving just Pearce and the convict with the axe—watching each other closely. Eventually it was Pearce who got hold of the axe, killing and eating his companion. Pearce struggled on alone, sustained by the human flesh in his pockets. He fell in with a group of sheep stealers and was recaptured along with them after almost four months on the run. Oddly, they were hanged but he managed to muddy the waters enough to talk the authorities into taking an extraordinarily lenient view of his crimes. He was sent back to Macquarie Harbour.

It was less than a year before he again absconded with a younger convict named Thomas Cox. Pearce was only on the loose for ten days, not long enough to need to resort to cannibalism. But he murdered Cox at King’s River, allegedly when he discovered the man could not swim. Then he ate him.

This time there was no escape. He confessed and was hanged in Hobart on 19 July 1824. In the tradition of alleged famous last words of notorious criminals, he is said to have stated, ‘Man’s flesh is delicious. It tastes far better than fish or pork’.

The ‘greatest monster who ever cursed the earth’ was the Van Diemen’s Land murderer, rapist and cannibal Thomas (sometimes Mark) Jefferies (Jeffries). From Christmas Day 1825 he and some accomplices carried out a number of callous murders, including that of a five-month-old baby whose brains Jefferies smashed out on a tree trunk. Running short of food, the bushrangers murdered one of their group while the foolish man slept. His flesh kept them alive for four days until they were able to slaughter a couple of sheep. They were still carrying about five pounds of human flesh when captured in late January. The Hobart Town Gazette reported:

The monster arrived in Launceston a few minutes before nine o’clock on Sunday Evening. The town was almost emptied of its inhabitants to meet the inhuman wretch. Several attempts were made by the people to take him out of the cart that they might wreak their vengeance upon him, and it became necessary to send to Town for a stronger guard to prevent his immediate dispatch. He entered the Town and gaol amidst the curses of every person whomsoever.

Jefferies was executed on 4 May 1826, alongside the gentleman bushranger, Mathew Brady, who is said to have protested against dying alongside the monster.

A few years later, another group of Van Diemen’s Land absconders served up an even more grisly tale of human flesh. Also from Macquarie Harbour, five men robbed the constable overseeing their labour on a settler’s outstation and took to the bush. They had one axe.

Not knowing how to live off the land, they soon ran out of food and drew lots to choose who would slaughter one of their number, Richard Hutchinson, to feed the others. Edward Broughton, a 28-year-old career robber, drove an axe into the unlucky man’s head. According to an account of their confessions: ‘They cut the body in pieces and carried it with them, with the exception of the hands, feet, head and intestines. They ate heartily on it, as Broughton expressed it.’

When their companion’s flesh was exhausted, the four fugitives began to eye each other: ‘The greatest jealousy prevailed about carrying the axe, and scarcely one amongst them dared to shut his eyes or doze for a moment for fear of being sacrificed unawares.’ Broughton and another man, Mathew Maccavoy, agreed to watch out for each other, one sleeping while the other kept guard.

The oldest man in the group was next to die. While the sixty-year-old known only as ‘Coventry’ was away cutting wood, the others agreed to kill and eat him. Broughton refused to do the deed as he had already murdered their first victim. So eighteen-year-old Patrick Fagan got the job:

Fagan struck him the first blow. He saw it coming and called out for mercy; he struck him on the head, just above the eye, but did not kill him; myself and Maccavoy finished him and cut him to pieces. We ate greedily of the flesh, never sparing it, just as if we had expected to meet with a whole bullock the next day.

The three remaining men were still feeding on Coventry’s flesh when Maccavoy suggested to Broughton that he should kill Fagan, the only witness to their crimes. Broughton refused. The two men returned to their campfire where Fagan was keeping warm. Broughton recalled:

I sat beside him, Maccavoy was beyond me; he was on my right and Fagan on my left. I was wishing to tell Fagan what had passed, but could not, as Maccavoy was sitting with the axe close by looking at us. I laid down and was in a doze, when I heard Fagan scream out, I leapt to my feet in a dreadful fright, and saw Fagan lying on his back, with a dreadful cut in his head, and the blood pouring from it. Maccavoy was standing over him with the axe in his hand:

‘You murdering rascal, you dog!’, I said, ‘what have you done?’

‘This will save our life’, he said, and struck him another blow on the head with the axe.

Fagan only groaned after the scream, and Maccavoy then cut his throat through the windpipe. We then stripped off the clothes, and cut the body into pieces and roasted it. We roasted all at once as upon all occasions, as it was lighter to carry, and would keep longer, and would not be so easily discovered.

A few days later ‘the remaining cannibals got kangaroo to eat off some wild dogs that killed the animal’. They then ‘threw away the remainder of Fagan’s body’. Just two days later they turned themselves in. The two men were hanged together at Hobart in 1831. Edward Broughton made a last confession of his grisly crimes as the hangman tied his arms together ready for the drop, concluding, ‘I wish this to be made public after my death’.

On his left arm he sported a tattoo of men boxing. His forehead was scarred and he was blind in the left eye. James Porter was born in London around 1800. He went to sea at fifteen years of age and stayed mostly in South American waters until 1821 when he returned to England and was convicted in 1823 of stealing some silk and fur. Transported for life, he arrived in Hobart in 1824 and soon began trying to escape.

By 1829 he had made at least three attempts to regain his freedom and suffered the ironed gangs as punishment. He was then sent to the grim Sarah Island in Macquarie Harbour. Even by penal station standards, the location was intimidating. Set in treacherous waters and accessible only from the sea through a narrow channel called ‘Hell’s Gate’, Sarah Island was designed to hold the most desperate convicts and re-offenders.

It quickly gained a reputation as the harshest prison in Van Diemen’s Land. Floggings, hard labour in irons and solitary confinement were routine as convicts felled timber for a shipbuilding industry the government hoped to establish. Escape attempts were routine. At one point, out of around two hundred convicts on the island, about one hundred were missing, believed escaped. Many were never seen again. After two years on Sarah Island, James Porter bolted again, only to be caught and punished with the usual flogging.

Finally, as Sarah Island penal station was closing down after a decade of misery, Porter found an opportunity to ‘once more chance my life for my liberty’. In 1834, with a group of other prisoners, he seized a brig, the Frederick. The convicts overwhelmed the two soldiers left on board and marooned them with the crew. One of the convicts could navigate and some, including Porter, could sail. But there was trouble from the start. One of the escapees deliberately ran them off course and was only just spared ‘a short passage over the side’, propelled by his irate companions. This incident was a forewarning of what was to come.

With fine weather and a good wind, they sighted the South American coast after little more than six weeks at sea. But the Frederick was leaking badly and they decided to abandon her and take to the ship’s only boat—‘I never left my Parents with more regret, nor was my feelings harrowed up to such a pitch as when I took the last farewell of the smart little Frederick,’ wrote Porter. They rowed ashore in the pre-dawn dark and when the sun came up, ‘we could see the shore close aboard of us covered with a rich verdure’.

Each of the convicts was armed with a brace of pistols and when they encountered a group of ‘indians’ they readied for a fight. But there was no need and they were directed to the nearest town and eventually were picked up by the Spanish authorities. Their story was that they were shipwrecked mariners. The governor questioned them but declared: ‘Sailors you have come on this coast in a clandestine manner and though you put a good face on your story I have every reason to believe you are Pirates and unless you state the truth between this and 8 o-clock tomorrow morning I shall give orders for you all to be shot—take them away.’

Porter responded with spirit:

We as sailors shipwrecked and in distress expected when we made this port to be treated in a Christian like manner not as though we were dogs; is this the way you would have treated us 1818 when the british [sic] Tars were fighting for your independence and bleeding in your cause against the old Spaniards—and if we were Pirates do you suppose we should be so weak as to cringe to your Tyranny, never (!) I also wish you to understand that if we were shot england will know of it and will be revenged—you will find us in the same mind to morrow we are in now, and should you put your threat into execution tomorrow we will teach you Spaniards how to die.

The room fell silent. After a few minutes the Spanish summoned a British naval officer and asked if he knew Porter. It turned out that the officer had sailed with him many years before. Porter and the convicts with him were taken back to their quarters. But one of their number was absent. They soon worked out that a persistent malcontent in their group named Cheshire betrayed them in return for the Spanish sparing his life. The men decided to tell their captors the truth, including Cheshire in the confession, to make sure they all hanged together.

The eloquent Porter was spokesman: ‘I told him the whole of the circumstance, but also stated that we would rather have died than given him any satisfaction but our motive in so doing was that Cheshire should not escape but share the same fate as us.’

The governor agreed and then released them, keeping Cheshire in custody for his own safety as he knew the other convicts would kill him given an opportunity. Besides, his carpentry skills were useful.

Porter and his companions now settled down as tradesmen and workers in the local Chilean community. Porter made good use of his skills, took up with several women, including a young Indian slave girl, and survived a drunken attack from a ‘mad brained sealer’. But he and his companions eventually found themselves back in confinement under the Spanish and awaiting the arrival of a British ship to take them back into custody: ‘I then gave up all hope of ever regaining my liberty, we had been Confined above 7 months Chained two and two like dogs.’

Porter managed to get himself separated from his manacled companion; however, ‘They put me on a pair of Bar irons, the Bar placed across my instep so that I could not stride or step more than 4 or 6 inches at a time’. Assisted by a woman of his acquaintance, Porter obtained a knife and file, eventually managing to grind through his manacles. Using the change of guards as his cover:

I shook off my irons, and reared a plank against the wall, I had no shoes on, I went back about 21 yards and on looking behind me saw the door open. I made a spring and ran to the top of the plank and with a sudden spring catched hold of the top of the wall; haul’d myself up, ran down a veranda on the other side and jumped off, being 12 feet from the ground.

He made his way through the darkened streets of the town, across the river in a stolen canoe and into the country, where he was at liberty for a few uncomfortable days. Suffering from dysentery, he was captured by Spanish soldiers. After more failed escape attempts, torture and the threat of being shot, Porter came to no longer care if he lived or died. But somehow he survived and was placed in British custody then returned via several ships to England. After interrogation and the revelation of their true identities as escaped convicts, Porter and his companions were transported once again to Van Diemen’s Land.

On the return voyage Porter was, falsely he claimed, accused of fomenting a mutiny aboard the transport. Once again, Cheshire and another of the Frederick convicts were the cause of his trouble as they informed against him:

I was seized by the soldiers lashed to the gratin and a powerfull black fellow flogged me across the back, lines and every other part of the body until my head sank on my breast with exhaustion, as for the quantity of lashes I received I cannot say, for I would not give them the satisfaction to seringe [surrender?] to their cruel torture, until nature gave way and I was senseless.

Chained together with the other bleeding accused conspirators, Porter ‘craved for death’. After three weeks of this treatment, the surgeon feared the fettered men were dying from their treatment and lack of food. They were released and the truth, or at least Porter’s version of it, came out. Cheshire, ‘the monster in human shape’, was confined below for the rest of the voyage.

They reached Hobart in March 1837, ‘when to the astonishment of all present I was known as one of the men that assisted in Capturing the Brig Frederick’. As they were taken off the ship, Porter managed to get close to the treacherous Cheshire: ‘I seized him by the throat and hurled him over my hip and would have throttled him but was prevented by the police.’

The convicts, in heavy irons, were tried for piracy and found guilty. The sentence would have been death but they escaped on a technicality. Porter spent almost the next two and a half years ironed in Hobart Gaol and was then sent to Norfolk Island ‘wer Tyranny and Cruelty was in its vigour’. But under a new and reformist commandant, Captain Maconochie, Porter responded to the improved conditions on the island and vowed he would ‘live in hopes by my good conduct to become once more a member of good Society’. He was later sent back to the mainland.

It was now twenty-four years after James Porter’s original sentence of transportation. He had seen neither his English wife or son in that time. He suffered Macquarie Harbour, Norfolk Island, the Coal River and numerous other jails in Australia, England and Chile. He survived floggings, beatings, torture and hard labour in heavy irons. In May 1847, Porter made his final escape attempt as part of a group who absconded from Newcastle on the brig Sir John Byng. He was never seen again.

Of the many bushrangers celebrated in folk tradition, Western Australia’s ‘Moondyne Joe’ is probably the least threatening. His clever escapes and non-violent career have given him a Robin Hood aura that is still strong today. But who was he?

Joe was imprisoned but while awaiting trial he escaped. Recaptured, the horse-stealing charges were dropped but he received three years imprisonment for jail-breaking. Released in 1864 he was returned to jail within a year, this time with a ten-year sentence. The charge was killing an ox with intent to steal the carcass and he was sentenced to hard labour in a working party. By now Joseph Johns was something of a legend among the convicts and settlers, reflected in his nickname ‘Moondyne Joe’. As if to prove his legend true, he soon escaped again.

When they caught him this time, the bushranger was given a further year in chains. Bound fast within a cell, Joe almost managed to escape yet again and so was placed in another, supposedly escape-proof cell in the prison refectory. It was only a matter of days before he disappeared from here and enjoyed several months of freedom in his old stamping ground around Moondyne Springs. But in September 1866 he was recaptured and held in a specially constructed escape-proof cell in Fremantle Prison. According to the local paper:

Mr. Hampton is said to have told him, when he saw him put into the cell which had been specially prepared for him, that if he managed to make his escape again, he would forgive him. That cell was made wonderfully strong, as much so as iron and wood could make it, and in it Joe was kept chained to a ring in the floor or wall, allowing a movement of about one yard, in heavy irons, with one hour’s exercise daily in one of the yards.

Here, in solitary confinement, on a bread and water diet and in an enclosed space with little light or air, he became so ill that the medical authorities said he would die.

For his health, Joe was taken out of his cell for most of the day and left in the corner of the prison yard by himself, watched closely by a guard and kept isolated from all contact. He was put to work breaking stones and eventually smashed a large pile of rubble behind which it was difficult for the guard to see what was happening. On 8 March 1867, all was normal: the guard watched Joe’s pick rising and falling behind the pile of rubble, occasionally checking verbally that the convict was still there. He was.

But what the lazy guard could not see was that Joe’s pick was not attacking rocks but a loose stone in the prison wall. As the heat of the day faded, the guard could see Joe’s cap over the rubble but could not get an answer from his call—‘Are you there, Joe?’ Seeing the cap, the guard assumed Joe was having a break and neglected to walk over to check until knock-off time at five o’clock.

Of course, when the guard finally went to get Joe, he found the cap and a broad-arrow jacket propped up on a couple of picks and a large hole in the prison wall. Joe had breached the supposedly unbreachable stone barrier, left his prison clothes behind and wriggled into the garden of the prison superintendent’s house. Then he simply strolled through the superintendent’s front gate which, fortunately, happened to be open. The West Australian press described Joe’s ingenuity in making this escape in delighted detail:

Joe then prepared for his exit, by sticking his hammer upright and with some umbrella wire he had got possession of, he formed a shape something of a man’s shoulders and arms; upon the top he placed his cap and having slit up the sleeves of his jacket and shirt, managed to slip out of them and leave them upon the frame he had constructed, then having got rid of his irons, and divested himself of his trowsers, got through his hole in the wall, passed through Mr. Lefroy’s yard and out at a side door to the front of the prison, whence to a person of Joe’s practised sagacity a safe transit to the neighboring bush became an easy matter.

Pandemonium! Prison authorities and the police scrambled to catch the great escaper once again. Governor Hampton, who had called Joe an ‘immense scoundrel’ and publicly boasted of the escape-proof cell, was especially displeased, which only increased the pleasure of the broad community of settlers and convicts. For them, Joe had now added another triumphant chapter to his legend and they sang in the streets, to the tune of ‘Pop Goes the Weasel’:

The Governor’s son has got the pip,

The Governor’s got the measles.

Moondyne Joe has give ’em the slip

Pop, goes the weasel.

Moondyne Joe had become a local hero. Not exactly a bush Robin Hood or a Ned Kelly, but an affectionately respected defier of colonial authority nevertheless.

After absconding from his ‘escape-proof cell’, Joe remained at large for another two years, and was eventually recaptured at a local vineyard on 25 February 1869, drunk according to some accounts. He served another lengthy sentence—without escaping this time—and mostly stayed out of trouble, working around the southwest and in Fremantle as a carpenter, shipwright and bush labourer. He even settled down to married domesticity with the widow Louisa Hearn (Braddick) in 1879. Louisa died in 1893 and Joe succumbed to increasing senility, passing out of life and further into legend seven years later.

Embellished versions of Moondyne Joe’s adventures and escapes are still told today. His many unlikely escapes from various jails and hostelries are favourites. So is his alleged crossing of what was then the new Fremantle bridge before the governor had a chance to officially open it in 1867.

He is commemorated with four statues in three countries as one of the great heroes of Irish resistance. Yet outside a small group of enthusiasts and historians, the Irish rebel John Boyle O’Reilly is barely known today.

After joining the clandestine Irish Republican Brotherhood in 1865, trooper John Boyle O’Reilly of the 10th Hussars was arrested, tried and convicted for his part in plotting a rising against the British government. He was to die by firing squad, but his sentence was commuted to twenty years penal servitude. With sixty-or-so other Fenians, as Irish rebels were known at the time, the 23-year-old O’Reilly was transported to Western Australia aboard the Hougoumont in January 1868.

When they arrived, the convicts were marched in chains to Fremantle’s forbidding limestone prison. They were bathed, cropped, barbered and examined by a doctor. Their physical and personal details were recorded and they were issued with the regulation summer clothing: cap, grey jacket, vest, two cotton shirts, one flannel shirt, two handkerchiefs, two pairs of trousers, two pairs of socks and a pair of boots.

O’Reilly was sent to work on the road gangs around Bunbury, one of more than 3220 convicts in the colony at this time. Later in his life O’Reilly would publish his novel, Moondyne, based on his convict experiences. He dedicated this work to ‘the interests of humanity, to the prisoner, whoever and wherever he may be’. In the novel, O’Reilly describes the bush and the work of the free sawyers:

During the midday heat not a bird stirred among the mahogany and gum trees. On the flat tops of the low banksia the round heads of the white cockatoos could be seen in thousands, motionless as the trees themselves. Not a parrot had the vim to scream. The chirping insects were silent. Not a snake had courage to rustle his hard skin against the hot and dead bush-grass. The bright-eyed iguanas were in their holes. The mahogany sawyers had left their logs and were sleeping in the cool sand of their pits. Even the travelling ants had halted on their wonderful roads, and sought the shade of a bramble.

He went on to contrast this with his own situation and that of other convicts toiling alongside him:

All free things were at rest; but the penetrating click of the axe, heard far through the bush, and now and again a harsh word of command, told that it was a land of bondmen.

From daylight to dark, through the hot noon as steadily as in the cool evening, the convicts were at work on the roads—the weary work that has no wages, no promotion, no incitement, no variation for good or bad, except stripes for the laggard.

O’Reilly’s education and literary skills soon gained him the job of clerical assistant to Henry Woodman, the overseer of the road gangs. In this capacity the young Irishman travelled with reports and messages to the Woodman family home and seems to have developed a romantic attachment to Jessie Woodman, the warder’s daughter. This ended unhappily, perhaps before it really began. In the poetry he wrote, O’Reilly expressed his despair:

Have I no future left me?

Is there no struggling ray

From the sun of my life outshining

Down on my darksome way?

Will there no gleam of sunshine

cast o’er my path its light?

Will there no star of hope rise

Out of this gloom of night?

Just after Christmas 1868, O’Reilly slit the veins of his left arm. He passed out but was found and saved from death just before it was too late.

Despite his despair, all was not lost for this transported revolutionary. His case became a popular cause of the day, taken up by those with a political conscience about the activities of the British government in Ireland. A powerful coalition of Irish republicans in the United States of America, elements of the Roman Catholic church and local sympathisers in Western Australia plotted to free the rebel. In February 1869 he was whisked away to freedom by a Yankee whaler. O’Reilly celebrated his twenty-fifth birthday in the middle of the Indian Ocean on his secret voyage back to England from where he made his way to America and freedom.

John Boyle O’Reilly went on to a glittering journalistic and political career in America. He remained deeply involved in Irish patriotic activities and is remembered by some in that country, in Australia and in the country of his birth as a great patriot. He played an influential part in the plot to free his companions still labouring in the West Australian bush. They bore the indignities and sufferings of convict life for seven years more while agitation about their plight and plots to end it slowly developed.

At Easter 1876, the rebels were rescued from bondage by an American whaler, the Catalpa, an exploit still celebrated in Irish communities around the world and commemorated in a well-known ballad. The verses tell the exaggerated but rip-roaring story of the bold rescue:

All the Perth boats were racing,

Making best tack for the spot,

When that Yankee sailed into Fremantle

And took the best prize of the lot.

In fact, the Catalpa went nowhere near Fremantle Harbour, laying off Rockingham, far to the south. When news of the escape reached the authorities, they hastily ordered the colony’s only armed vessel, the Georgette, to undertake an ineffectual pursuit of the Yankee whaler. Approaching the American vessel, the Georgette came close enough to hear her captain yell out that if they fired on the ‘stars and stripes’ he had hoisted in the yards, it would be an act of war against the United States of America.

The Georgette well-armed with bold warriors

Went out the poor Yank to arrest.

But she hoisted the star-spangled banner

Saying ‘You will not board me, I guess’.

The master of the Georgette decided that this might be true and allowed the Catalpa and her rescued rebels to sail away.

Now they’re landed safe in America

And there will be able to stay.

They’ll hoist up the green flag and the shamrock

‘Hurrah for old Ireland’, they’ll say.

And indeed the Fenians were safe. The British government and the colonial authorities all had egg on their faces and sympathising Irish people everywhere celebrated the escape, just as they had hailed O’Reilly’s earlier triumph. Both escapes were accomplished without violence and provided two further stirring incidents in the extensive folklore of Irish resistance to British rule, even more delicious for the American role in the escape.

Come all you screw warders and gaolers,

Remember Perth Regatta day.

Take care of the rest of your fenians

Or the Yankees will steal ’em away.