CHAPTER SIX

Legacy of Family Trauma

At times of trauma, the natural response is to run, but not necessarily running from, as much as running to. Trauma survivors typically run toward home, but where do you go when the trauma is in your home?

When it is not safe psychologically or physically to be who you are, to own your truth, what you see, and how you feel, then you move into various trauma responses—you fight, you flee, or you freeze.

Your mother is standing over you, her face distorted in her anger, she’s telling you she never wanted you in the first place. You are to stay out of her bedroom. The drugs are hers. She now is threatening to send you to live with your father who you don’t even know. You are nine years old.

You witness your father hitting your older sister; he’s raging at her and now threatening to hit your mother. In that moment, you hate him. You don’t care that he just lost his job. You don’t care that your mom says you are to be grateful for what you have. You hate him. And you hate yourself because you feel so powerless.

How can you fight back? Where can you flee to? Is your only option to freeze emotionally, to go numb inside?

The body cannot tell the difference between an emotional emergency and physical danger. When triggered, it responds by pumping out stress chemicals designed to impel you to quickly move to safety or enables you to stand and fight. In the case of childhood problems, where the family itself has become the source of stress, there may be no opportunity to fight or flee. So you do what you can. You freeze, shut down your inner responses by numbing or fleeing on the inside.

Your dad is loaded on his cocktail of drugs and is raging. A tired mom, one who used to try to protect you, now sits frozen on the living room couch. You want to run to the bedroom or outside but know that is a useless attempt. He’ll just chase after you and get you. You want to scream you hate him and you know that will only make things worse. His rage could escalate and you and your brother who is also a witness to this could get hit, or maybe he would just tell you how worthless you both are. You just want to disappear. You remain standing but feel nothing, as if you just disappeared from yourself. You swallow the whole scene; the experience becomes embedded in your body and brain. This moment, this scene, gets added to the folder that holds all the previous ones. They all begin to blend together as you create a portrait of who you are.

The very people you want to flee from were those you needed and loved. The very people you should be able to go to for protection are the ones traumatizing you.

To live with fear on a chronic basis fuels ongoing traumatic stress, regardless of whether it is the consequence of more blatant or covert trauma. Without protection factors to override the impact of trauma, flight, fight, and freeze responses will be acted out.

Emotional Legacies of the Fight, Flight, and Freeze

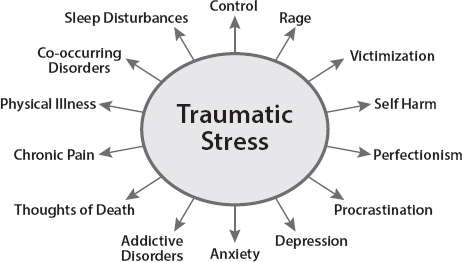

Survival is about defending against your pain that aligns itself well with the fight, flight, and freeze responses. While the most apparent consequence of growing up with addiction is the generational repetition of becoming addicted and engaging in relationships with someone with addiction, even more common are the following trauma responses.

Control

Children learn to control in two ways: external and internal. The responsible child is often the master of external control, manipulating people, places, and things. This is the child who is the parent to brothers and sisters and to him- or herself. As Cam said, “I raised myself rather well.” Tim set the bedtime for his younger brother and sister and made sure they had bathed and were tucked in. He made their lunches for school the next morning. Kimberly would call her father to tell him what he needed to do when he came home from work. All children are likely to try to control the internal, intangible aspect of their personal lives. They do that by withholding their feelings and diminishing their needs, neither expecting nor asking for anything.

• I am not angry. What is there to be angry about?

• I wasn’t embarrassed. I’m used to those things by now.

• I don’t need to go to my friend’s house. Who would be home to take care of my sister?

• I don’t want a birthday party. My dad wouldn’t show up anyway.

This is self-control, protection to ward off further pain by repressing desires and feelings. As a child, the attempt to control internally or externally was about survivorship. It made sense in the context of your environment.

Unfortunately, the continued need for control causes problems in adult lives. You have spent years being hypervigilant and manipulating others as a way of protection. You literally don’t know how to live life differently. Unfortunately, because of being so encapsulated and narrow in your view of the world, it’s not possible to see what others can so readily see—that you have become authoritarian, demanding, inflexible, and perfectionistic.

Controllers don’t know how to listen; cut people off in conversations; don’t ask for help; can’t see options; have little spontaneity; experience psychosomatic health problems; intimidate people by withholding feelings. Blindly focused on the pursuit of safety, very often unaware of your emotional self and yet so frightened and full of shame, you rely on what you know best—control. But the consequences are almost the opposite of what was hoped for. Your needs do not get met; relationships are out of balance. Ultimately, hypervigilance becomes burdensome and exhausting. In confusion about what has gone wrong when you have tried so hard to make things right, controllers resort to unhealthy ways of coping with pain that often results in addictive behaviors.

Perfectionism

While the issue of perfectionism may seem trite to some people, others wish they were more perfectionistic. Sadly, I have worked with many people who have attempted to take their lives in despair as their perfectionism has failed them. That ultimately has them concluding nothing they would ever do is good enough for them to be okay. Perfectionism is a major contributor to depression and anxiety.

Perfectionism is driven by the belief that if a person’s behavior is perfect there will be no reason to be criticized and he or she can only be admired. And as well as children perform, often achieving lofty goals, perfect children have learned that no matter what they do, it’s never good enough. As a result, in the struggle to feel good about themselves and relieve the source of pain, they constantly push to excel, to be the best at any cost. Yet there is always something missing once the goal is reached—there is always another goal, something more to complete.

Highly perfectionistic people are usually those who have been raised in a rigid home environment. The rigidity may be in the form of unrealistic expectations that parents have for their children. In these situations, you internalize your parents’ expectations. Rigidity is also experienced as children feel the need to do things right in order to gain approval from their parent and to lessen fears of rejection. For most children, doing things right is perceived to mean there is no room for mistakes. What is then felt is that “no matter what I do, it’s never good enough” and, for the young person, that becomes translated into “I am not good enough.”

Children of addiction are taught to strive onward. There was never a time or place to rest or to have inner joy and satisfaction.

Perfection as a performance criterion means you can never measure up. Not measuring up is translated into a comparison with others of good versus bad, better versus worse. Inevitably, you end up feeling the lesser for the comparison. This comparison with others is one of the primary ways people continue to create more shame for themselves. The messages you heard growing up are the messages you continue to give yourself. You no longer need others to tell you to do better or what you do is not good enough. You do that fine by yourself. Since your efforts were never experienced as sufficient, adequate, or good enough, you did not develop an internal sense of just how much is good enough. As a consequence, there is always a hole in your gut, an emptiness, a sense of incompleteness. And for some, ultimately, a hopelessness.

I developed a perfectionist mind-set; anything short of being number one meant failure.

Procrastination

Perfectionism and procrastination are closely linked and people often identify with engaging in both. Procrastination, such as starting but not completing a project or considering a project but never initiating it, is often an attempt to defend against further shame. Some people procrastinate because in the desire to do things perfectly recognize it will never be good enough or their efforts won’t be acceptable, so they stop or find safety in not trying.

For others, they received so little attention that they were not encouraged to initiate projects, let alone complete them. Too many times when they did something, drew a picture or wrote a story, and gleefully showed their mother or father, their parents barely looked at it and then set it aside or maybe even lost it. Without positive reinforcement to complete school projects or homework, children perform with ambivalence. They believe no one else cares and develop the attitude “Why should I care?” The result is procrastination.

It is possible you were humiliated for your efforts, made to feel inadequate or stupid. When that happens you find ways to protect yourself so you cease involvement in any action that would prove you really are a failure. In addition, you become discouraged when constantly compared to someone who did or might have done it better.

My two older brothers did well in school. They were quick to think on their feet and they were articulate. It took me longer to grasp things. I wasn’t as interested in math and sciences as they were. I was more interested in my friends. So, with school being more of a struggle and having no real help from my parents, only the push that “you should be like your brothers,” I just gave up. I wasn’t like them and didn’t want to be. So I just quit trying. I wasn’t going to do it good enough anyway.

Also mixed into procrastination may be anger, expressed as an attitude of “I’ll show you—I won’t finish this” or “I’ll only do it part way. I won’t give my best.” Inherent in this attitude is a challenge that screams, “Like me for who I am, not for what I do.” In a family where rigidity is the rule, where it is not okay to make mistakes, or to not be acknowledged for accomplishments or to have them demeaned, children learn not to initiate or finish what was started. For those raised this way, it is amazing anything gets completed.

If I did something wrong while I was driving, my father would backhand me in the mouth. Needless to say, it wasn’t easy to drive with tears, frustration, and anger. I had four learner’s permits by the time I was eighteen. I was twenty-two before I had enough courage to get my license, and I was twenty-seven before I could drive on the freeway. I still get scared today to try new things. I put them off and in many cases I simply don’t try.

Victimization

I knew nothing about relationships. I didn’t know what was appropriate to give in a relationship so I just gave, gave, and gave. I didn’t know what my needs were. I didn’t know how to ask for what I wanted. I didn’t know what I wanted. I had learned no one really cared or was interested. My needs had never been met so I didn’t expect that. So one relationship after the other, they were all alike. They took advantage of me; I have been slapped around a lot. I leave every relationship with less than I go in with.

People who succumb to the victim role do not know how to say no. They are struggling with the internalized beliefs of “I am not worthy,” “I am not of value,” “Other people are more important than me,” or “Other people are more worthy,” that will sabotage setting limits. They often have no boundaries or have distorted boundaries. The desperate longing for nurturance and care overrides the willingness to establish safe and appropriate boundaries with others.

Victims have learned not to trust their own perceptions, believing that another person’s perceptions are more accurate than their own. They give others the benefit of the doubt and are willing to respond to the structure others set. Victims are skilled at adhering to the dysfunctional family rules. Victims operate from a position of fear, unable to access any anger or indignation that comes with being hurt, disappointed, or abused. When asked what they need or want, victims often literally do not know.

Almost inevitably, victims have great difficulty protecting themselves in the context of intimate relationships. They are often attracted to someone who appears to have the ability to take charge, make things happen. This is someone who very likely feels strengthened by association with the victim’s vulnerability. Becoming highly skilled at rationalizing, minimizing, and, often, flatly denying the events and emotions in their lives, victims develop a high tolerance for pain and inappropriate behavior. To name hurtful or inappropriate behavior may be perceived as inviting more trouble in to their life. While the victim response is the result of the belief in personal powerlessness, it is also a defense. Victims believe they may not have as much pain if they give in and relinquish autonomy to someone else.

While some victims stay in isolation, those who don’t often play a combination of the victim/martyr roles: “Look at how I am victimized. Aren’t they terrible for doing this to me! I will just have to endure.” Being the victim becomes part of a cycle. Victims already feel bad about themselves as a result of being abandoned and/or abused and don’t act in a manner that could create safety and security leading to greater abandonment or abuse.

For all of the reasons noted above, whether male or female, the shameful person is at great risk of repeated victimization.

When I would hitchhike, guys would pick me up and not let me out until they got what they wanted. Then they would kick me out of the car and I’d put out my thumb again.

Rage

Rage compensates for an overwhelming sense of powerlessness; it is the holding tank for accumulated fears, angers, humiliations, and shame. It is intended to protect against further experiences of pain. Emotionally, it is an attempt to be heard, seen, and valued when you are most desperate and lacking in other skills. When you have lived with a chronic sense of helplessness combined with fear, rageful behavior offers a sense of power. When rage is the only way people know to protect against emptiness, powerlessness, and pain, the choice is a quick one.

In my rage I don’t feel inadequate or defective. It may be a false sense of power I feel, but if all I have ever known is my powerlessness, I’ll take false power over no power.

Rageful behavior also offers protection by keeping people at a distance. As a result, other people cannot see into the raging person’s soul that he or she believes to be so ugly.

Many times people who are rageful grew up with parental rage. It was often the only model for attempting to be heard or to garner control. Rage as a defense also offers protection by transferring shame to others.

The outwardly rageful person chooses a victim-like person who, consciously or not, is willing to take the abuse or assume the shame. The rager chooses to live with people who become the chronic victim(s) of his or her rage; or move around a lot, wearing out his or her welcome after relatively short periods of time in one place.

I had always looked outside for the answers. My life was such a mess and everything I did was just making it worse. I had been so lonely, so frightened. I had felt so empty and didn’t know why; alcohol and rage were my answers. And I became addicted to the high of both.

Growing up some children find anger to be their one safe feeling. This leads to other vulnerable feelings being masked with anger. Many people full of rage show no sign of other emotions. They keep a tight lid on all of their feelings until something triggers an eruption and suddenly their rage is in someone else’s face. Perhaps it is a scathing memo at work or an outburst of criticism toward a waiter or grocery store attendant. This is what I refer to as machine gun bursts.

The person who rages is often best described as holding a gas can in one hand and a lit match in the other.

While some people outwardly show chronic rage, others live with an internalized, simmering anger—a silent rage. When anger is held back and internalized, it grows. It festers into chronic bitterness or chronic depression. When there has been no outlet for anger, it is more apt to explode suddenly as a significant single hostile act.

Examples of this are the highly publicized acts of school violence and shootings across the country. The shooter is often described as having shown no previous signs of aggression. Much of the time the shooters were described as being loners or simply different, but not overtly violent.

After further investigation, however, it was discovered that these troubled individuals carried burdens of buried rage, often the result of being bullied within the family or by their peers in the schools that manifested in an act of deadly violence.

Rageful behavior is a combination of the inability to tolerate vulnerable feelings and the inability to resolve conflict and/or perceive options and choices. These dynamics are common consequences to growing up with addiction.

While my mom was the one addicted to alcohol and drugs, my dad was addicted to his rage. He would fly off the handle at anything and everything. He would rant and rave and kill you with his words. He actually looked like he enjoyed it. The scenes were right out of a movie. Only they were very real for us. I swore I wouldn’t end up like my dad, and yet that is exactly what I do today. I understand the high he got in his rage; I understand the power he felt. And it is destroying everything in my life.

Depression

For many, depression is a biochemical imbalance or disordered neurochemistry, best treated with antidepressants. It is commonly accepted among professionals that depression tends to run in families, suggesting there may be a physiological predisposition toward depression. But depression is also induced by external experiences. For a number of people, it is a consequence of a habitually pessimistic and disordered way of viewing the world. Living with addiction certainly makes one see the world in a negative and chaotic manner. Depression is also the consequence of loss and the inability to do the grief work necessary to bring completion to the feelings of sorrow. It can be referred to as pathological grief. It is also a traumatic stress response when your survival response is to freeze, your neuro system is in a chronic state of hypoarousal that fuels depression.

A depressed person is typically pictured as one who sleeps excessively, is unable to eat, and is suicidal. While that picture represents the severe end of the depression continuum, many depressed adults are able to function daily and meet many of their responsibilities. After all, for the adult child it has been his or her survival mode. Remember, looking-good children are often those who maintain the appearance of doing just fine outside while dying slowly on the inside. Children in addictive homes develop the skill of compartmentalizing. As a child, you may have cried yourself to sleep at night or lashed out in anger or hidden in fear, but when you got to school you didn’t tell anyone about your feelings or experiences. You present yourself to the world as “I am fine; life is fine; and nothing is amiss.” You present a false self who may not have had the look of depression, while your true self—emotional and spiritual self—was experiencing great despair. This is practiced day in and day out, week after week, month after month, and year after year. It easily becomes a skill that becomes a defense. As a consequence, many adult children do not demonstrate blatant depression but are a part of the walking wounded, the closeted depressed.

To keep depression hidden, people avoid sharing with others on an intimate level or avoid spending time with friends who may recognize their true feelings and internal despair or emptiness. They rely on defenses of busyness and accomplishing tasks. They deliberately keep the focus on other things and other people. They appear very capable and put out an impenetrable force field that says, “Don’t ask me about myself. Don’t push me.”

It is difficult enough being depressed. It is even more difficult when you have shame around it—shame that fuels depression and more shame because you are depressed.

There is tremendous loss associated with being raised in a shame-based family. With the family being denial-centered, as it often is, and it not being okay to talk honestly, the sense of loss is amplified because there is no way to work through the pain. The hurt, the disappointment, the fears, and the anger associated with life events are all swirled together and internalized. Add to this a personal belief that says, “I am at fault” or “I am not worthy,” then it is easy to see why you come to believe in your unworthiness and try to hide your real self from others. Eventually, you hit an emotional wall. The burden of hiding eventually becomes too heavy and all of those protecting, controlling mechanisms that kept your depression closeted just stop working. The ability to compartmentalize becomes so diminished and you are no longer able to hide the depression. By the time many adult children show obvious (overt) depression, it is usually little more than the final eruption of a long-term, chronic, closeted, hidden depression.

I didn’t even know I was depressed until I was no longer depressed. I had always lived like this. I functioned. I operated in the world. I had a good job, family. But I have never felt joy. Oh, I am very socially skilled; no one knew how I felt over the years. Then one day, I just couldn’t keep the pretenses up. None of my old defenses kept working. It was like I hit a wall I did not see coming.

Anxiety

A generalized anxiety disorder is marked by unrealistic worry, apprehension, and uncertainty. Think about that as a child growing up with addiction. There is so much uncertainty, unpredictability. Of course you would be apprehensive and, as a consequence, hypervigilant and worry about every possibility. As an adult that constant state of worry, apprehension, and hypervigilance has now become an habitual way of protection and survival. It may be unrealistic, but it is also a trauma response.

Courtney was raised in a physically abusive, alcoholic family. Between the ages of seven and twelve, she was also sexually abused by her older brother. At the age of thirty-six, she is self-supporting but lives her life quite isolated. She is hypervigilant to the first sign of danger, physical and emotional. She perceives danger when she feels misunderstood, not agreed with—limiting her social world considerably. She has been in the same job fifteen years, not wanting any advancement or change, liking the security. She is far too frightened of intimacy to allow herself a close and loving relationship. She lies awake at night, listening to noises, or frequently wakes up in the night, startled and unsure of her safety. From the outside, she simply looks like someone more introverted and content to live her life this way. All the while, she is simply trying to contain her fears. Courtney is struggling with anxiety that is a part of her post-traumatic stress.

As Courtney has done, most adult children accept their anxiety as a way of life, using their skills in denial and rationalizing as they live their daily lives.

Self-Harm

Those who struggle with depression and anxiety as a result of trauma often engage in physical acts of self-injury. The most common acts are cutting and burning, but self-harm can take many forms such as incessant pinching of skin or head-banging. While it makes no sense to the thinking brain that to escape from persistent pain you would create more physical pain, the act of self-harm often generates a dissociative response or a feeling of release and relief in the moment. It’s an attempt to regulate the painful emotions of anger, sadness, anxiety, and shame.

Sleep Disturbances

Many adult children report they have difficulty sleeping with nightmares being common. They are hypervigilant to noises, feeling the need to be prepared to protect themselves and to respond to the threats that seem to always be lurking. Never having established a sense of emotional safety, the past plagues them. Substances are a common solution to nightmares, sleep disturbances, and internalized shame. For many, sleep time is the most challenging time.

Physical Illness and Chronic Pain

Traumatic stress contributes to digestive and autoimmune problems; it contributes to diabetes, heart disease, and various cancers. When the body is repeatedly plunged past its normal limits, it begins to break down. Long-term trauma responses can tax the body and create inflammation, compromising the immune system that in turn makes the body more vulnerable to illness. The Adverse Childhood Experiences Study (see Appendix) that has been ongoing for over twenty years alarmingly shows a direct relationship between primary diseases and trauma. Experts in treating chronic pain see a direct relationship between trauma and physical pain in that the unhealed emotional trauma exacerbates the sensation of pain. The strong emotions of terror, sadness, grief, and shame become embedded in the body. There are several theories as to why this is so with evidence pointing to the chronically heightened stress response due to trauma occurring in the same parts of the brain that register pain.

Co-occurring Disorders of Depression, Anxiety, and Addiction

Depression and anxiety are frequently masked with addictive disorders.

Janet, raised with a single-parent drug-addicted mom, was ultimately treated for both depression and anxiety after her second divorce from two long-term marriages to addicts. Until the divorce, she had not reached out for help and by the time she sought it she was experiencing a major depression. She was experiencing slurred speech, the inability to make decisions, extremely poor self-care, diminished expectations, etc. The depression was treated with antidepressants. What then became obvious was a long-standing anxiety disorder. She fretted and worried about every minor and major detail in her life. Everything in life was a potential problem. To ask basic questions of someone in a store would send her into an emotional panic. Multiple times she was taken to the emergency room thinking she was having a heart attack to be diagnosed with a panic attack. What would not be identified because the mental health issues were more blatant and those doing the assessment did not include an addiction assessment, was that she had been addicted to pills for many years.

Ryan started experiencing panic attacks shortly after he began recovery from his compulsive overeating. He was raised in an alcoholic family with a schizophrenic mother who subjected him to extremely cruel physical punishments. Food had always been his medicator. Without the sugar and without any recovery from the emotional pain in his life, his fears quickly rose to the surface and he was hospitalized three times for what would ultimately be diagnosed as panic attacks characterized by intense anxiety, often a feeling of impending death, heart palpitations, shortness of breath, and sweating. Having been the victim of physical or sexual abuse strongly contributes to the likelihood of experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder.

Brad, thirty-six, had seen two family members die from their addictions yet here he was sitting at home in seclusion, with curtains drawn, drinking himself into oblivion. He was beginning to miss work on a regular basis. Fearful he would lose his job, he sought help. Three years sober, he found himself one more time, at home in seclusion, with curtains pulled. Although he was not drinking, he was in absolute despair. Once more, Brad would reach out for help. This time he would be treated for depression—depression that was present prior to getting sober but was not recognized. It was a depression strongly fueled from growing up with a lot of trauma in an addictive family.

Substances are seen as an answer to those who are depressed and anxious. Some people are looking to be numb, others are using to get a rush, to experience something different and greater than what they feel. Addiction to behaviors are common as well. Substances and processes both have satiating and arousal behaviors. Certain acts of gambling are more sedating, such as slot machines; others more arousing, such as horse racing or day trading. Some sexual behaviors are sedating and calming while others involve the arousal of risk. High intensity sports, contact sports, or the applause of an audience only elevate one’s emotional state. Forms of escape or excitement are quick answers to a complex problem—the trauma of growing up with addiction.

When I gamble I feel a rush. I feel I hold the world in my hand. My concentration is so focused, every past, present, or future problem is obliterated from my reality!

I was engaged in compulsive masturbation by the time I was ten. As my parents kept me awake with their arguing late into the night, I found solace, peace, in self-touch alone in my bedroom. I began to drink beer, whiskey, anything I could find about age thirteen to medicate the shame I was feeling around my sexual behavior. Then I found if I drank enough, I felt this courage to approach girls sexually. As I got a bit older, then I discovered that if I used amphetamines I could go for hours sexually, then I‘d use the alcohol to keep me from thinking about what I was doing. I am an addiction binger and trader. In time, it wasn’t just sex, alcohol, drugs, I would satisfy my craving needs through food, work, anything, to try to feel normal.

Thoughts of Death

I am hopeless. I am unworthy. And I don’t deserve to live.

If you live with enough fear, enough shame, and enough hopelessness, it only makes sense that at some point you begin to consider that maybe it would be better to not feel at all. It’s so difficult to let people know that your despair and self-loathing takes you to that darkness, to that place of thinking you would be better off not being here at all. This thinking is far more common than not. This isn’t a blatant suicidal thought; it is a thought though that can ultimately lead to finding solace in the concept of death. If you experience that thought frequently, the concept of death can become a comforting friend. The point being, people who grow up with trauma are certainly more apt to make a suicide attempt because they already have a friend in the thought of death. Suicidal thoughts and attempts are often a reflection of anger, rage turned inward, or the result of major depression. For some people, the attempt and act of suicide compensates for the powerlessness in their life. For most, death is perceived as a better option than living with certain memories and shame. The pain is too overwhelming. Out of despair and hopelessness, people become their own victims.

Life won’t get any better, and I can’t stand this pain.

If you find yourself thinking about the comfort of no longer being here or thinking about suicide, speak up and let someone know how frightened, angry, or hopeless you are feeling.

Repeating the Patterns

Whether or not the words it will never happen to me were ever spoken or just assumed, people raised in an addicted family system, despite all their good intentions, experience unhealed trauma and are more likely to repeat the familial patterns.

Addictive Disorders

If your great-grandfather, your grandfather, and your father had red hair, there is a strong probability that you have red hair and some of your children will, too. Addictive disorders and their many ramifications are similar. They, too, can pass from generation to generation. Though not all addicts learn their drinking and using behavior at their parents’ knees, children frequently imitate the styles of their parents. When you come from a pain-based family, you frequently go outside of yourself for a quick answer to relieve your suffering. You need someone or something to relieve this intolerable pain, take away your profound loneliness, fear, and shame, so you seek a mood-altering experience. You need to escape. When you grow up in an environment where the cause of pain is external, you develop the belief that the solutions to problems exist only through substances or behaviors.

I can remember my first drink. I was eleven. I hated the taste, but I felt the glow and it worked. I would get sick as a dog and then swear on a stack of Bibles I would not do it again, but I kept going back. I got drunk because I had a hole in my gut so big, and alcohol and then other drugs would fill the hole. They became the solution.

Whatever one’s drug of choice, it can quickly become an anesthetizer. It is most likely the one modeled and most accessible. So if you grow up with a substance-use-disordered parent, it is often substances; if you grow up under the influence of a gambler, it is gambling; if you grow up in a family with sex addiction, you find yourself a sex addict as well. Or not. Possibly because you are so driven to make sure it will never happen to you, you seek out a different substance than your addicted parent. If dad was addicted to alcohol, you don’t touch it, but you love your marijuana, you love your prescription pain pills, your meth. You don’t recognize an addiction is an addiction but from the brain’s viewpoint, substance and process addictions are identical.

Addiction is about the continued practice of an activity or the continued use of a substance despite negative consequences that ultimately interfere with portions of your life. Both substances and/or process addictions stimulate and reward the same neural pathways in the brain. Dopamine and adrenaline trigger the brain’s pleasure reward center; serotonin lessens anxiety and depression; endorphins do both and reduce pain as well. These neurochemicals have another attribute—they increase your ability to later recall how great you felt. This encourages you to repeat the same experience again, again, and again. Addiction is not so much about a specific substance or activity as it is about disrupting the normal procession of pleasure and process of thinking. The part of the brain that allows you to think rationally, see choices and consequences, when under the influence, becomes hijacked leaving the brain to not consider consequences.

With the exception of some illicit drugs, these substances are an integral part of our culture, socially sanctioned and supported, making it very difficult for the abuser to initially recognize he or she is using them in unhealthy ways. In addition to temporarily controlling the emotional pain, the substances used and abused very often provide something one does not know how to seek naturally. They offer an illusion of power to someone who has known only powerlessness; courage and confidence to someone who feels lacking in both. This is certainly drug-induced, temporary, and false, but for many people, false courage, confidence, and power is better than no courage, no confidence, and no power. For someone who is isolated and feels alienated, the addictive behavior or substance may make it easier to reach out to people and not feel so alone. “Give me a little bit to drink and I become alive. I pull myself away from the wall and I find myself talking, laughing, and listening. I see people responding to me and I like it.” This doesn’t mean that a person is addicted, but it does mean he or she is thirsty for connection with others. And to maintain that connection or that sense of power or courage, is a set up to want a second, third, and fourth drink, toke, snort, or whatever in order to feel more calm, whole, and complete.

People who have never taken time to play or laugh because life has been so serious find alcohol gives them the opportunity to relax. Anne identified, “My entire life has been spent taking care of other people. I am always busy. I make these lists daily, thinking the world will stop if I don’t get the job done. I don’t think about missing out on fun—it has never been a part of my life. I never drank until I was twenty-six. I don’t even know why I started. Those first few times I heard myself laugh with other people it actually scared me. I remember thinking that I was being silly as if that was bad. Yet at the same time there was this attraction. It was as if there was this whole other part of me I didn’t know and maybe was okay to know. The attraction to relaxing with alcohol kept getting stronger. I can actually remember thinking, I don’t have to make this decision tonight or I don’t have to do this by myself. Pretty soon, it was I don’t have to do this at all. I was having fun. Life wasn’t so hard.”

Because Anne did not know how to relax, she was tightly controlled in her thoughts and emotions and she ultimately became dependent. She, like so many others, was seeking wholeness. But the only glimpse she had of feeling whole, feeling complete was under the influence.

Addictive behaviors, whether they are substances or processes, provide something the adult child has not learned to acquire naturally, such as courage, confidence, laughter, power, or connections to others. Common process addictions range from compulsive activities, such as gambling, gaming, spending, sexual behaviors, disordered eating behaviors, relationship dependencies, work addiction, and compulsive busyness. People use any and all of these to distance or distract, to get their mind off their pain. Many behavioral compulsions would be otherwise harmless activities if they weren’t exaggerated, destroying the balance in your life. For example, exercise is a healthy activity until done so excessively that you injure yourself. Addiction is about living in the extreme without a sense of moderation.

By fourth grade I was preoccupied with food. I told myself in a proud way that I was addicted to Coca-Cola, just like Mom was addicted to booze.

Spending and shopping give me a sense of power. For just a little while it can feel so great.

There was so much pain I was forever seeking ways to escape. As a child it was food, fantasy reading, and television. I was always looking for someplace safe. I never felt safe. I never felt good about myself or even adequate. I was never enough. My sex addiction is about paying for women who will not reject me. They are safe. I get consumed with the ritual of finding them; it’s me in a fantasy world again. All the pressures I feel, the anxiety that for me comes with living, are gone. Then I go back to my guilt and shame, and then cycle back to the hunt.

As with addictions, abuses repeat themselves within families as well.

Dad was a great teacher and I was his prize pupil. I picked up all of his self-centeredness, dishonesty, demanding, false promises, his addiction, and his outright abusive behavior, plus all of the guilt, remorse, and low self-esteem that goes with it. I had always sworn I’d never be like Dad—but ultimately I got there.

While not all abusers learn their behavior in their parents’ home, the overwhelming tendency is to punish as you were punished, to resolve conflict the way you saw it resolved, to construct your relationships as your parents did, and to continue to tolerate the levels of abuse you witnessed in childhood.

Just as you comment to yourself or others it will never happen to me, convinced you will not become addicted or ever marry someone who is addicted, the adult child does that with violence as well. Anger burns out of control in abusive families. As a result, the child is usually someone who becomes anger-avoidant, terrified of any anger, his or others, or he, too, becomes abusive in his anger. Children of anger frequently marry or are in committed relationships with someone who is chronically angry or rageful, or abusive in his or her own anger.

I was so afraid of any conflict, any anger, I’d do anything to placate, to please my husband, but in reality that did very little to stop his rage.

I would have private temper tantrums. I’d throw things, slam doors, and swear a lot. I’d become enraged at the slightest frustration—getting stuck in traffic or losing my keys and not being able to get the door open. All the things I’d locked in as a child were slowly slipping out.

I was a strict disciplinarian. I would spank and then lose control. I always responded to whatever my kids did in a physical way. Afterward, I would be so appalled by what I had done. Even more so, I was appalled I was just like my father. I felt mortified with shame. But I couldn’t seem to stop myself, and the beatings continued.

Self-hate is overwhelming for the person raised with violence. Low self-esteem, coupled with a pervasive sense of powerlessness and fear of conflict, often compels someone to choose a partner who also has low self-esteem and acts out his or her low self-worth in a similar manner. The person raised with violence has internalized the words and behaviors that repetitively said she was worthless; she was not deserving; she would never amount to anything; or she couldn’t do anything right. Such individuals frequently succumb to depression, believing in their helplessness and hopelessness. Others resort to addictive behaviors. Many become abusers.

Alicia was sexually abused by her father, her brothers, and then her brother’s friends. She was having sex with any guy she knew by the time she was a teenager. “I was fourteen and all I knew about myself was I could do two things well. One was to drink and the other was to get a guy to bed. They were my points of pride.”

Often sex is the only way one knows to get attention because it is basically the only way he or she was ever given attention. Alicia’s only validation for being was through being sexual and, ultimately, she found her only power through sex. Promiscuity is a misguided search for love, nurturing, and acceptance, but it does not work. Alicia went to treatment for drug abuse when she was twenty-three, but she would also be treated for sex addiction and the underlying trauma of being sexually abused.

It is easy to be involved in sexually abusive relationships when one’s sexual boundaries have been repeatedly violated. As the survivor feels dirty and doesn’t know how to say no, more shame is incorporated, greater helplessness is experienced, and then more repetition occurs.

Josh, raised by two substance-abusing parents, experienced more covert sexual abuse by his father and more blatant abuse by his mother. His father wouldn’t allow the boys to wear nightclothes, and then he would wander the house nude and drunk. He teased the boys mercilessly about their sexual development. His dad often drank outside of the home, leaving Josh home alone with his mother where she did her drinking. The older brothers were often out on the streets. “I needed love and attention from my mom, but then she’d go into this striptease and molest me. I wanted her to stop, but I didn’t know how. I felt so powerless. I thought I should have known what to do, how to get myself out of this situation. I should have been a grown-up and done the right thing. I had this terrible sense of shame because I didn’t know what to do. I didn’t know how to get away from my pain.” Josh started making suicide attempts beginning at the age of nine, and began drinking and using Valium by age twelve. He moved into his sex addiction in his later teens and began to sexually abuse and traffic young girls.

The combination of the physical act of being victimized, improper role modeling accompanied by feelings of fear, guilt, anger, and shame leads to various fight, flight, and freeze responses for the child. Addiction for so many is the fight and the flight.

Repetition in Relationships

As surprising as it is for the person involved, it is as common for children raised with addiction to marry or to enter into committed relationships (and often times more than once) with someone with an addiction as it is for them to become addicted to a substance or behavior. And it is just as common if they experienced physical or sexual abuse for that to occur in the context of their new family as well.

Dynamics that create the likelihood of repetition:

• The stage of progression is significant particularly for people in their first adult relationship. When both you and this partner are younger, you are more likely to have met when he or she is in the earlier stages rather than middle or late stages of the addictive disorder. Many adult children are less likely to have any memory of their addicted parent’s early stage behavior. By the time you are old enough for memory, your parent is into the middle or even later stages of his or her addiction. It is very difficult to identify addiction in the earlier stages, as the behaviors are so inconsistent.

• The person you partner with may be addicted to a different substance or behavior than the one you were raised with so you don’t see the blatant similarities. To assure yourself you don’t marry someone like your parent, for example, someone who is alcoholic, you marry someone who drinks very little or not at all. But, lo and behold, he or she ends up being addicted to cocaine or another drug, or they have a process addiction, such as gambling, porn addiction, or another addictive process.

• You recognize your partner has a problem, but you tell yourself you can handle it. You believe you have the advantage of knowing what to expect. After all, you have handled your parent’s problem and you tell yourself you can handle this as well telling yourself it won’t be that bad. You loved your mother or father in spite of his or her addiction, and you will love this person in spite of his or her addiction.

• Adult children often have what is called impoverished expectations—you don’t expect enough. This is usually based in low self-esteem, not believing you deserve differently or better. It is also based in having had years of minimizing, denying, and pretending things are other than they are. That doesn’t change just because you are older.

• Another adult-child trait is a high tolerance for inappropriate behavior that allows the addictive behavior to not be recognized for what it is, and to minimize the pain and disruption it causes you or the relationship.

These multiple factors make it very easy to repeat a family pattern.

As I was growing up, I remember really wanting only one thing—to be able to do it differently than I saw it being done around me. So, when, two days before my twenty-third birthday, my husband was put in jail for a felony DUI, I looked into the passive eyes of my child, whom I had just thrown across the room, and felt my world and my sanity crumble. I was doing it just the same way they had done.

Due to the dynamics of growing up with addiction, relationships in general can be problematic. The modeling you had was controlling, abusive, apathetic, noncommittal, acrimonious, and, often, addictive. Leaving you to engage in similar, controlling, abusive, apathetic, noncommittal, acrimonious, and addictive behaviors. You believe your worth and value only exists within the context of a coupleship. Relationship dependency is fueled by low self-esteem and lack of a strong sense of self. The adult child uses the relationship as proof of worthiness. In an addictive relationship you use other people to lessen your shame and to avoid facing yourself. To be outside of a relationship is too frightening. To be alone often puts you in touch with your emptiness. Being in a relationship allows you to focus on others without having to address your own pain. The problem with this is it’s a set up to tolerate hurtful behavior, to not be assertive, and to not grow. At the price of your own well well-being, the adult child will go to any lengths to maintain or get into a relationship.

Signs of relationship and love addiction:

• Confusing love with intensity and/or frequency of sex.

• Being with a partner who is unavailable or highly controlling.

• Compromising values in order to secure or keep a relationship.

• Lacking boundaries, not being able to say no when you want to.

• Intimacy is based in fantasy and magical thinking.

• Living in fear the relationship could end at any time, after all, you believe you are not good enough.

• Engaging in high-risk sexual behaviors; the risk-taking often out of fear of losing the relationship.

• Rushing into another relationship prematurely, often having a potential partner waiting in the wings.

Shelly captures the core of relationship and love addiction, “I have been married and divorced five times, and now I realize I never divorced the right man all along, my father.”