CHAPTER SEVEN

The Adult Child Begins Recovery

Children raised with addiction move into adulthood with incredible strengths as a result of survivorship. They pat themselves on the back and don’t want to look behind at the past, but in time they begin to experience problems as a result of:

• The inability —to trust their own perception.

—to trust others.

—to identify needs.

—to identify feelings.

—to listen.

—to relax.

—to initiate.

• Fear —of feelings.

—of conflict.

—of rejection or abandonment.

• The need to control.

• Impoverished expectations.

• Unrealistic expectations.

• High tolerance for inappropriate behavior.

• Approval seekers.

• Rage.

• Depression.

• Substance use disorders.

• Process addictions.

• Disordered eating.

• Repetitive addictive relationships.

To some degree we can all be affected by these issues. But the phrase “some degree” is important here. Adult children experience these difficulties to an extreme; difficulties that can interfere with the ability to genuinely discover happiness and meaningfulness in life. It is my belief that adult children deserve more than the ability to survive.

Recovery begins with accepting two basic rights:

1. The right to talk about the real issues.

2. The right to feel.

Steps in Recovery

Judith Viorst wrote in Necessary Losses, “It is true that as long as we live we may keep repeating the patterns established in childhood. It is true that the present is powerfully shaped by the past. But it is also true that insight at any age keeps us from singing the same sad songs again.”

To be able to put the past behind and not repeat those same sad songs, adult children need to take the following steps.

• Explore Past History

You need to explore your past, your childhood years, to discover and acknowledge your reality, not to assign blame. It is my belief that family members truly want the best for each other and that begins with self-honesty. You aren’t betraying your parents or siblings when you become honest about your reality. If there is an act of betrayal, it is with the addiction, the dysfunction of the family system. When you do not talk honestly about your experiences you ultimately betray yourself.

Exploring past history means asking questions such as “What happened that was hurtful to me?” and “What didn’t I have that I needed?”

To let go of the past you must be willing to break through denial to be able to grieve the pain. In other words, you need admit to yourself the truth of what happened, rather than hide or keep secret the hurt and wounds that occurred. It is difficult to speak honestly today when you have had to deny, minimize, or discount the first fifteen or twenty years of your life. There is no doubt denial became a skill that served you as a child in a survival mode. Unfortunately, denial, which begins as a defense, becomes a skill that interferes with how you live your life today. You take the skill of minimizing, rationalizing, and discounting into every aspect of your life. When you let go of denial and acknowledge the past, it gives you the opportunity to identify your losses and to grieve the pain associated with those losses. It is the opportunity to genuinely put the past behind. Exploring the past is an act of empowerment.

In the process of exploring your past, you are also doing grief work. Grieving that which you never had, grieving the losses that occurred. This takes you into the second step.

• Moving into Your Emotions

These steps are not linear, these two steps in particular are extremely entwined. Talking honestly about the past remains an intellectual exercise if the feelings that accompany the experiences are not acknowledged and felt. Because it is emotional and trusting yourself with feelings is not necessarily the strong suit of most adult children, it is important to have a safety net in place. When you have a history of cutting yourself off from feelings and they begin to rise, it often feels like a tsunami of all kinds of feelings. You need to know and to trust a support system.

Feelings have often been experienced as something to dread, to be afraid of. To be willing to embrace them, it is helpful to recognize the gifts they offer. For example, anger often leads to energy for those who have been immobilized or frozen and if used well leads to assertiveness; fear links to a gift of alertness and preservation; guilt allows people to make amends and helps keep them in touch with their values; with joy one can access gratitude. All feelings when listened to are cues and signals that tell you what you need. “I’m scared and confused … I need …” “I am sad … I need …” For the adult child who struggles with knowing his or her needs, it begins with knowing his or her feelings. Feelings don’t necessary indicate action is needed as much as they need to be heard and listened to. You are the first to do that with yourself. Keep in mind that exploring your feelings is far more important than accessing particular memories.

As noted this is only one step in the healing process. If it is the only step you take it becomes a blaming process not a grief process. Blaming parents has never been the intent of adult-child recovery nor should it be. In your recovery you need a venue, be it with a therapist, support group, or a workbook where you need to say things such as “It wasn’t fair.” “They were wrong.” “They hurt me.” This is a part of owning the experience. So much of what has occurred was wrong and it hurt. Today you have lived with the consequences. As you move through recovery you now need to be accountable for the choices you make around your own healing.

• Connect the Past to the Present

The purpose for connecting the past to the present is because the present is that which is most important. You cannot do anything about the past, but since your current life is so strongly influenced by your childhood experience, it is essential to take these steps so that you can reflect and grieve those aspects of your past. That being said, it is your life today that you want to fulfill. Connect the past to the present means asking, “How does this past pain and trauma influence who I am today? How does the past affect who I am as a parent, in the workplace, in a relationship, how I feel about myself?” The cause-and-effect connections you discover between past losses and present life will give you direction. These questions allow you to become more centered in the here and now. This clarity will identify the areas to focus on in recovery.

• Challenge Core Beliefs

Challenge core beliefs means asking, “What beliefs have I internalized from my growing-up years? Are they helpful or hurtful to me today? What beliefs would support me in living a healthier life?” Adult children often internalize beliefs such as “It is not okay to say no” or “Other people’s needs are more important than my own” or “No one will listen to what I have to say” or “The world owes me and I am entitled” or “People will take advantage of me every chance they can.” Many of the beliefs adult children have internalized are shame-based. “Who I am is not okay.” “I am not worth anything.” “I am defective, damaged.” On the other hand, you may have internalized beliefs that said, “There are people who care,” “I have value,” “I deserve to live my life differently,” etc. An important part of recovery is identifying, challenging, and letting go of specific beliefs that fuel self-defeating behaviors and low moods and recreating new beliefs that support you in the way you deserve to live. It is also recognizing childhood beliefs that supported you in a healthy way and continuing to embrace them. Today you can take ownership for maintaining those beliefs.

• Grounding Practices

It will be difficult to do the above steps without engaging in grounding practices, which are ways to help you stay emotionally stable versus reactive or numb. These are tools that assist you in emotional regulation to not move into fight, flight, or freeze responses. To heal you need some inner stability, and you garner that when you have healthy ways in which to soothe yourself and feel safe in your own skin. Grounding practices are essential in every step of healing. They are not meant to be used a few times but throughout your entire recovery process. The good news is they are readily available and many of you may find you have already naturally gravitated toward them. That could account for some of the resiliency you are already demonstrating.

Some common forms of grounding include:

■ Arts, such as painting, pottery, sculpting, photography.

■ Crafts, such as beadwork, needlepoint, woodworking, quilting, knitting.

■ Dancing.

■ Singing.

■ Time in nature.

■ Time with animals.

■ Gardening.

■ Engagement in martial arts.

■ Tai Chi.

■ Yoga.

■ Meditation practices.

As said, these practices are not meant to be used once or twice, Ideally, they are regular practices you integrate into your life. They calm racing thoughts, improve your ability to concentrate, increase energy, reduce anxiety, lessen depression, reduce emotional reactivity, inspire creativity, and increase compassion for yourself and others. They can be fun and can offer meaning in your life.

• Learn New Skills

All children of addiction learned important skills that are helpful to them. Reflect on the skills you learned that were helpful. Some learned to problem-solve, to take charge and lead, others established goals, some became good listeners, and others developed specific talents such as cooking. But what were the skills you did not learn? You may not have learned to ask for help, to set limits for yourself, to express feelings in a healthy way, or to relax. Reviewing the progression of the roles in Chapter Four will help you identify some of those skills. The question you need to ask yourself is “What did I not learn that would help me today?” Many skills were learned prematurely and were developed from a basis of fear and shame. When that occurs there is a tendency to feel like an imposter and in those situations, addressing the feelings and beliefs associated with the skill will make it more likely you can feel greater confidence in those skills. You were resilient and those skills you get to keep.

This step and the next are the two that are most linear of all of them. This means the previous steps need to be taken before you act on these. The reason for that is the skills you may want to learn that you didn’t get to learn as a child have both an emotional component and a belief system attached to them. And those feelings are often painful and the belief system often self-defeating due to it emanating from a traumatic childhood. For example, a good behaviorist can help you learn the skill of limit-setting, role-play situations in which you demonstrate the skill. Yet in real life, when you go to practice, you hit a wall if you did not address the emotions and beliefs that many years ago were attached to the experiences that made it unsafe for you to learn this skill. It is possible you couldn’t set limits because you came to believe you didn’t have the right to protect yourself or that when you set limits others wouldn’t like you. Those are beliefs that continue to get in the way of the skill if you don’t identify and challenge them and create new ones in their place. In addition, the emotional pain you felt at those times in childhood when you wanted to set limits for yourself but couldn’t and, therefore, often felt sad, embarrassed, or afraid, still need to be acknowledged. To learn new skills requires feeling safe within yourself to acknowledge feelings and to identify the beliefs that could sabotage the new skill.

The change you want to create in your life will be made directly as a result of undoing your denial process and grieving the pain. It means recognizing the connection of the past to present day. It necessitates owning the beliefs you want to carry and letting go of old, hurtful belief systems and learning skills that were never modeled or the opportunity never afforded. With the incorporation of grounding practices into these steps it becomes possible to create a new narrative for yourself. These steps walk you through owning a narrative of your past, a past strongly impacted by addiction. Now you have the opportunity to create and live a new, more positive narrative that comes with the tools of your recovery and healing.

You no longer have to live with the script of the past but have choices as to how you live your life.

The following exercises are a start to your self-exploration.

Breaking the Don’t Talk Rule

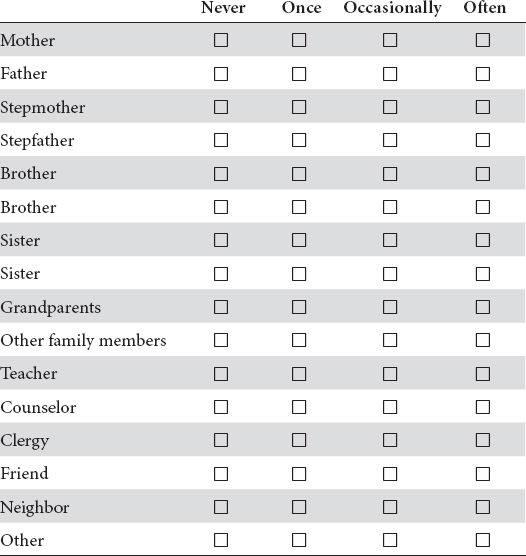

One of the consequences of growing up in a home with the Don’t Talk rule is that people develop a silent tolerance for inconsistencies, untruths, and painful feelings. Reflect on people you may have talked to about problems at home when you were a young child and teenager. Check the frequency with which you can remember talking about problems to your:

In some instances, certain issues were present in your family life that may have prevented you from talking about problematic areas of your life. Circle those that were true for you:

I felt ashamed.

I felt disloyal, as if I were betraying. I was embarrassed.

I didn’t understand what was occurring well enough to talk about it.

I was afraid I wouldn’t be believed.

I was specifically instructed not to talk.

It was insinuated in nonverbal ways that I should not talk.

It seemed as though no one else was talking.

I believed something bad would happen if I talked.

I came to believe that nothing good would have come from talking.

If as an adult, you still have difficulty talking about your growing-up years put a check ( ) by the above statement(s) that apply to you today.

) by the above statement(s) that apply to you today.

List the people in your life today with whom you already are or are willing to talk to about your growing-up years:

1. _______________________________________________________

2. _______________________________________________________

3. _______________________________________________________

4. _______________________________________________________

5. _______________________________________________________

6. _______________________________________________________

7. _______________________________________________________

If you:

• Feel a sense of shame when talking about your growing-up years, try to understand that you weren’t at fault—your parents would have liked it to have been different.

• Feel a sense of guilt, trust that you are not betraying your parents, your family, or yourself. If there is any betrayal, you are betraying the addictive system.

• Feel a sense of confusion about your childhood, that’s probably an accurate description of how life has been for you—confusing. When attempting to explain irrational behavior in a rational manner, it will sound confusing. Talk—it will help you develop greater clarity.

• Fear that you will not be believed, a great deal of information is available that will substantiate that your experiences are not unique.

• Have been instructed, specifically or nonverbally, not to talk, recognize that instruction was motivated by fear or guilt. You don’t have to live that way any longer.

• Have experienced something negative from people you spoke with in the past, you are now free to choose a healthier support system.

• Have been conditioned to believe that “nothing good comes from talking,” put faith in the belief it is only when you finally begin to speak your truth that you will be able to put the past behind and experience the joy of the present.

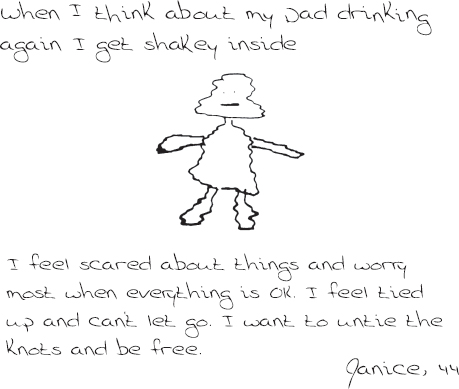

Breaking the Don’t Feel Rule

Painful feelings are more likely to lessen when you are able to talk about them. When you don’t express these feelings they accumulate. As a scared young child, you began rolling your feelings up in a bundle like a small piece of snow rolling down a hill and now these feelings have become a giant snowball. By the time the snowball reaches the bottom of the hill—by the time you have grown up—the feelings have been piled up, painful upon painful feelings. No wonder you are scared. It’s understandable that when you do get in touch with all your feelings, you may feel overwhelmed.

Present-day disappointments, losses, angers, and fears become intertwined with old disappointments, losses, angers, and fears, making it difficult to separate the old issues from the new ones. Having a feeling does not mean you need to act on it. How one feels and what one does with those feelings are separate issues. In early recovery, being aware of your feelings and identifying them are significant. Let your feelings be your friend, not something to be denied or minimized. Feelings are not there to rule you, but to be cues and signals to tell you something. Acceptance of feelings, combined with the ability to express them, will decrease fear and generate greater inner confidence. Feelings seem inappropriate only when they are not understood.

• What are the messages that interfere with your willingness to show specific feelings?

• Where did you get these messages?

• What is the price you pay for maintaining these messages?

If you are inexperienced at owning your feelings, it will be important for you to know the value of being able to identify and express them. Some benefits are:

• When I know my feelings and am more honest with myself, then I have the option of being more honest with others.

• When I am in touch with my feelings, I will be in a better position to be close to other people.

• When I know how I feel, I can begin to ask for what I need.

• When I am able to experience feelings, I feel more alive.

Identify two more reasons that are of value to be able to identify and express feelings.

Remind yourself of these messages by writing them down and posting them in a visible place or using them as affirmations to support you on a daily basis.

From the list below, circle the feelings with which you identify.

Love |

Shame |

Fear |

Happiness |

Worry |

Guilt |

Sadness |

Confusion |

Discouragement |

Frustration |

Anger |

Loneliness |

Hurt |

Embarrassment |

Jealousy |

Hate |

After you identify what you are feeling, note when and where you experience these feelings. If the identification of feelings is difficult, practice this on a daily basis. Try to share these with another person. The more specific you can be about your feelings, the more you can understand and accept them, and the more apt you are to be able to do something constructive with them. While positive feelings are the ones people seek, negative feelings can be viewed as cues or signals that can give information about what is needed.

When I feel sad, it may mean I need support.

When I am angry, I probably need to clarify my stance.

When I am scared, I need to let someone else know that.

By viewing the more painful feelings as signals, it is easier to accept them and to utilize them constructively. By identifying feelings, one is less apt to be overwhelmed by emotion and end up depressed, confused, or enraged.

With the following exercise you can gain insight into and awareness of family patterns. On a scale of one to five—one being the least often expressed, five being the most often expressed—rate your parents’ frequency of expression.

FEELINGS |

Mother |

Father |

| Love | 1 2 3 4 5 | 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Fear | 1 2 3 4 5 | 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Worry | 1 2 3 4 5 | 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Sadness | 1 2 3 4 5 | 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Discouragement | 1 2 3 4 5 | 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Anger | 1 2 3 4 5 | 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Hurt | 1 2 3 4 5 | 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Jealousy | 1 2 3 4 5 | 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Shame | 1 2 3 4 5 | 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Happiness | 1 2 3 4 5 | 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Guilt | 1 2 3 4 5 | 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Confusion | 1 2 3 4 5 | 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Frustration | 1 2 3 4 5 | 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Loneliness | 1 2 3 4 5 | 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Embarrassment | 1 2 3 4 5 | 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Hate | 1 2 3 4 5 | 1 2 3 4 5 |

You can also ask yourself which feelings you wanted expressed more often, and which ones less.

Can you see any repetitive patterns for you in adulthood?

Crying: The Expression of Sadness

As a child you may have learned not to cry or to cry silently alone. Thirty-six-year-old Anthony, a recovering addict, was talking about crying. He said he was the child who never cried. When he was very young, he remembered crying only once, and that was when a dog died. He entered adolescence and adulthood being “tough” and “surviving.” Anthony told his counselor about his complete inability to shed tears over any of his personal misfortunes, which included his nine hospitalizations for addiction. Surrender is essential for an addict’s recovery. It includes the breaking of the denial system about one’s situation in life, mentally, emotionally, physically, and spiritually. Anthony’s surrender began when the tears started to flow the day he was admitted to his tenth treatment program. He needed to cry—he needed to quit being “tough,” “alone,” and in the denial trap of not talking, not feeling, and not trusting. The tears were the breakthrough. If you are an adult child who can identify with patterns of not crying or crying alone and silently, know your tears are not there to hurt you—they are there to cleanse your grief, your pain.

While many adult children struggle with the willingness to cry, there are those who find themselves frequently crying, yet not understanding the reason for the tears. Some find they cry at inappropriate times, while others find they cry at the appropriate times, but there is an overabundance of tears. They feel as if the depth of tears does not match the trigger. Cheryl, thirty-five, says, “I’m so tired of crying. I never cried as a child, and today I cry at the least little thing. I cry if I get scared; I cry if I feel rejected; I cry if I hear a sad story on the news; I cry when I read a nice, warm story on the internet. I don’t seem to have any control. It’s really embarrassing, but more than anything, it depletes me.” In Cheryl’s case, her crying incessantly has occurred in the first few months of her recovery process. The intensity and the frequency lessens when you are getting support at the same time. You have a lot to cry about and more likely than not it feels foreign. People describe feeling out of control, which is understandable when you have spent years working hard to hold in your pain. Holding the pain inside is what felt safe, sharing it, exposing it will feel foreign initially because it is unfamiliar to you. In time, you will feel relief. It is important to 1) recognize the need to cry; 2) give yourself permission; 3) let another person know about this; and 4) let that other person be available to offer support.

You will need to reevaluate the messages you previously received about crying, such as “It doesn’t do any good to cry”; “Boys don’t cry”; “Only sissies cry”; “I’ll smack you harder if you cry.” New messages need to be “It’s okay if I cry”; “It’s important that I allow myself to cry”; “It’s a healthy release”; “I’ll probably feel better.”

As a child what did you do with your tears?

• Did you cry?

• Did others know when you were crying?

• Did you let others comfort you when you were crying?

• What did you do to prevent yourself from crying?

Now ask yourself:

• Do you ever cry?

• When do you cry?

• Do you only cry when alone?

• Do you cry hard, or do you cry slowly and silently?

• Do you cry because people hurt your feelings?

• Do you cry for no apparent reason?

• Do others know when you cry?

• Do you let others comfort you when you cry?

• What do you do to prevent yourself from crying?

• Do you get angry with yourself for crying?

• How is your pattern as an adult different from that of a child?

Read through these questions again, slowly, and then share what you know about yourself with another person. Choose a person with whom you feel safe—a therapist, a twelve-step member, a sponsor, a friend—someone with whom you feel you can allow yourself to be vulnerable. Remember, they may have old messages about the stigma of crying, too, and might welcome the opportunity to talk about an issue many people never take the time to explore.

You may also need to think about the basis of your fear. For the highly controlling person, fear of crying usually means a fear of falling apart. It is a fear of losing control; the fear that once crying starts, it will lead to hysterical behavior or that you will be unable to stop. The greater your fear, the greater the need to let others offer support. Recognize the need to establish a situation that is both protective and healthy. While crying may feel frightening, you do not need to fear you will go into hysteria. You may cry for five minutes, even ten minutes. As a therapist, I have seen hundreds of people cry, and they never needed to be carted away! Remember, you have accumulated a great deal of unresolved feelings. Your tears are usually related to sorrow, confusion, loneliness, and loss.

Fear

You may experience an overwhelming sense of fear. Much of the time that fear is unidentifiable. These fearful times are often episodic, periods of extreme fearfulness contrasted by periods totally devoid of fear. On the other hand, you may find yourself existing in a perpetual state of unidentifiable fear.

Many people are fearful of expressing their needs, fearing a loss of love should they express a want. Dawn said, “I’ve grown a lot, but I still feel gut-level fear when I express my wants and needs to my husband. It’s difficult to be spontaneously open and self-disclosing. I’m afraid he won’t love me.” As you move from childhood to adulthood, you may continue to experience fear of confrontation. While most confrontation is a simple disagreement or questioning, as an adult child your experience was different. These fears persist because there was never any constructive or healthy disagreement within the family. Any expressed disagreement resulted in yelling and loud arguing because the parent could not tolerate anyone disagreeing with him or her. Disagreement was perceived as betrayal and resulted in actions that belittled and condemned the child.

Adult children who experienced a lot of fear of the unknown, never knowing what to expect next, will continue to experience uncertainty and fear of the unknown. The fear of the unknown can keep one immobilized, and being stuck in fear itself immobilizes one emotionally. It will result in a tendency to discount one’s own perceptions and not have the courage to check out other people’s perceptions. The results are isolation, low self-esteem, and, frequently, depression and anxiety.

Answer the following questions:

• What did you fear as a child?

• Did you fear you were going to be left alone?

• Were you afraid you were going to get hit?

• Were you afraid your mom or your dad did not love you?

• What did you do when you were fearful as a child?

• Did you go to your room and cry?

• Did you hide in a closet?

• Did you ask a brother or sister to come and be with you?

• Did you wet the bed?

• Did you mask your fear with anger?

• Did others know that you were afraid?

• Do you think your mom or dad knew?

• Do you think your grandparents knew?

• How is that pattern similar in your adulthood?

• Do you still go off by yourself when afraid?

• Do you still get angry instead?

• Are you sharing your fears with someone, or are you still pretending you’re not afraid?

Ask those questions of another adult, someone you trust, and share your answers with one another. A goal in recovery is not to feel less than or be immobilized in fear. Fear can be a wonderful motivator and certainly a cue to what you may need.

Anger

The feeling of anger is natural to everyone, but when you are raised with addiction, anger is often repressed, twisted, and distorted. Adult children are usually either totally detached from, extremely frightened of, or overwhelmed by their anger. If you don’t feel anger, ask yourself, “Where did it go? Why isn’t it safe?” Be open to the fact that anger does exist. It is there. It just may not be very visible. When it was not safe for you to own your anger you take it elsewhere and it gets manifested in a multitude of ways—depressive behavior, overeating, oversleeping, placating, and illness, self-harm, addiction, psychosomatic problems. You may have experienced living with chronic anger or rage or an always-simmering low-level of anger or anger avoidance. Often one parent operates on one extreme, while the other parent is at the opposite extreme. Anger is often expressed through a tense silence, through mutual blaming, or through one-sided blaming coupled with one-sided acceptance. Typically in adulthood, the adult child repeats one of those extremes and most often chooses a mate to parallel that pattern.

Rich, age thirty-one, was aware of his anger but didn’t find outlets for expression. “I have needed to let go of the bitterness and hatred. I see I have denied myself so much. I have not let myself get close to anybody, men or women. I have allowed myself to be eaten up inside. Oh, I looked okay to the world and have done okay in my work, but I can’t let anyone get close enough to me or they would see this ugliness.”

Jaclyn described the consequence to her fear of any conflict erupting into violence. “After four years of marriage in which there were very few arguments, I woke my husband one morning and said, I’m leaving now, and smiled.” She said there had been no discussion of her wanting out of the marriage or her wanting anything to be different. She said she wasn’t angry, she simply wanted out. She had never been allowed to disagree as a child and when her husband raised his voice, which she said wasn’t too often, she’d simply agree to his wants. She walked out of a marriage that possibly could have been saved had she had the ability to simply disagree, had she had the ability to express what it was she needed or wanted. But for her, the fear of dealing with anger, either her own or her husband’s, was too great to risk.

While some adult children are anger-avoidant and many others chronically angry or simply bitter about life, all have a definite need to resolve issues. While anger is a natural human emotion, what you do with anger is learned and can be reshaped to better meet your own needs. Remember, feelings are a natural part of you, use them as signals to help direct you.

Now ask yourself:

• What did you do with your anger as a child?

• Did you swallow and not become aware of it?

• Did you play the piano extra hard?

• If you played sports, were you more aggressive than you needed to be?

• Did you hit your brothers and sisters?

• Did you go to your room and cry?

• What did other family members do with their anger?

• Did your mom or dad just drink more?

• Did your brother just shrug his shoulders and go outside and play with his friends?

• Did your sister just cry silently?

• Are you afraid you will go into a rage?

• Is there a fear about what would happen if you really acknowledged your anger today?

Talk with others about their anger. Ask them what they get angry about. Ask them how they express their anger. Compare patterns. You’ll find out you are not alone.

Make a list of all the things you could have been angry about as a child.

Example:

• I could have been angry with my dad for hitting my mom when she was drunk.

• I could have been angry with my dad for giving my dog away.

• I could have been angry with my mom the time she passed out on Christmas Eve.

• I could have been angry with my mom for not listening to me when I told her dad was drunk.

Now, make a list of things that as an adult you could be angry about but aren’t.

Example:

• I could be angry with my dad for never getting sober.

• I could be angry with my sister for never going to see my mom.

• I could be angry with my husband for not being more willing to listen to me when I want to talk about my mom or dad.

• I could be angry when I think people have taken advantage of me.

When you have approximately four or five examples of situations in which you could be angry as a child or adult, draw a large “X” across the words “I could have been” and “I could be” in every one of those sentences. Then write, “I am,” “I was,” or “I am still,” depending on whether or not you are still angry.

Example:

• I am still angry with my dad for hitting my mom when she was drunk.

• I am angry with my dad for never getting sober.

• I am still angry with my dad for giving my dog away.

• I was angry with my mom the time she passed out on Christmas Eve.

• I am angry when I think people have taken advantage of me.

• I am still angry with my mom for not listening to me when I told her Dad was drunk.

• I am angry with my husband for not being more willing to listen to me when I want to talk about my mom or dad.

Now, reflect on those sentences and thoughts—be aware of how you feel.

If you are working on this exercise with someone, tell him or her how you feel. Is it difficult to admit your feelings? Some of you will find relief in simply acknowledging past pain. Others won’t like the feelings at all. Remember, acknowledging anger, as well as other feelings, is a necessary part of the recovery, and the more you share your experiences with yourself and with others, the more comfortable recovery will be for you. A secondary benefit is an increased closeness and bond with those friends with whom you choose to share your feelings.

Recognizing and challenging anger constructively will allow you to identify your needs. Anger will help you identify limits and boundaries you need to set. When owned and expressed constructively, it will give you the courage to be self-caring.

Guilt

Imagine holding on to guilt about something over which you had absolutely no control, Imagine doing that for ten, twenty, thirty years, possibly a lifetime. When children take on guilt for things they are not responsible for they invariably continue to add more and more guilt to an already existing load.

I met Charlie when he was seventy-four years old. He came to me asking if I would participate in a task force for a local helping agency. After he had introduced himself and told me about the needs of the agency, he admitted he was not familiar with my work but had been told by others that I worked with kids whose parents are alcoholics.

I acknowledged the information he had been given was correct, and I began explaining the nature of what I do. I had been speaking for only about three to four minutes when he interrupted me suddenly, saying, “Yeah … yeah … my dad was alcoholic. Uh, he died.” His gaze dropped from my eyes, and he began looking fixedly at the floor. “Yeah,” he said. “I was thirteen.” His gaze turned to the ceiling. “He was thirty-one or thirty-two, I guess. Died in an accident. He was drunk when it happened.” Haltingly, he continued, “You know, I never understood. I never understood. You know I tried to be good. I never knew what he wanted though. I know I did things he didn’t like, but I wasn’t a bad kid.”

Charlie had carried his guilt for sixty-one years. He was not rambling in semi-senility, he was feeling pure guilt. He still believed he was responsible for his father’s drinking and, ultimately, his father’s death. He had carried all these years of guilt because he had no understanding of the disease process.

James told me, “I have carried guilt feelings throughout my life because I didn’t want the responsibility of raising my brother and sisters. I deserted my mom when I was eighteen and joined the army. I deserted her—just like my alcoholic father.”

For one and a half years in Al-Anon, Julie, age thirty-five, has been seriously addressing her issues around guilt. “I have a lot of issues to deal with about my mother—her constant criticism, guilt because I didn’t know why I was being criticized, and finally, my guilt for being alive.”

People need to reassess those things for which they held themselves responsible. The Serenity Prayer, which is the hallmark philosophy of Alcoholics Anonymous and Al-Anon, says,

God grant me the serenity

To accept the things I cannot change,

The courage to change the things I can,

And the wisdom to know the difference.

The more you understand, the easier it is to accept that you aren’t responsible for your parents’ addiction or their behaviors. It is important you realize that as a young child you had only emotional, psychological, and physical capabilities to behave as just that—a child. Once you have accepted that, it is easier not to be so self-blaming and guilt ridden.

Think about the guilt you still carry. Do you ever say, “If only I had … “? Take some time right now to examine your guilt feelings by working the following exercise.

• As a child, if only I had …

• As a teenager, if only I had …

Now, seriously answer, would any other six-year-old, twelve-year-old, or eighteen-year-old in the same situation, with the same circumstances, have behaved any differently? In fact, even as a twenty-five-year-old or a thirty-five-year-old, without knowledge of addiction and its many ramifications, would it be possible to respond differently? As an adult, the tendency to accept all guilt is a pattern that needs to be broken.

Ask yourself:

• What did I do with my guilt as a child?

• Was I forever apologizing?

• Was I a perfect child making up for what I thought I was doing wrong?

It is important to gain a realistic perspective of situations that you have the power to affect. Adult children often have a distorted perception of where their power lies and as a result live with false guilt. True guilt is remorse or regret we feel for something we have done or did not do. False guilt is taking responsibility for someone else’s behavior and actions.

Because this is usually a lifelong habit, it is important to go back and delineate historically what you were and were not responsible for. That will assist you in being more skilled in recognizing a lifelong pattern of taking on false guilt and stopping it.

Rewrite the following sentence stems and fill in the blanks. Write “No,” in the first blank, and then continue by finishing the sentence:

______ I was not responsible for ______________________________

when he/she did ______________________________.

______ it wasn’t my fault when _______________________________

__________________________________________________ .

______ it wasn’t my duty or obligation to

__________________________________________________ .

Then take the time to write about anything else you might feel guilty about that wasn’t your fault. When people feel guilty, many times they end up crying, looking as if they are sad or disappointed, or twisting the guilt into anger. Disguising one’s true feelings by putting up a false front is a common practice. Out of the need to survive, people will create distorted expressions of feelings.

What do you feel guilty about?

• Little things in everyday life.

• Everything in everyday life.

What do you do when you feel guilty?

• Buy presents for the person toward whom you feel the guilt.

• Get depressed.

• Get angry.

• Berate yourself.

When you are feeling guilt, a simple exercise is to ask yourself:

• What did I do to affect the situation?

• What can I do to make it any different?

• Can I accept that I did all that I was able to do with the resources available?

Give yourself permission to make mistakes. Take responsibility for what is yours, but don’t accept responsibility for what is not. You will need to work on your self-image and your ability to understand and express your own fear and anger, as well as to learn ways to deal with your guilt.

The possibilities for masking feelings are many. Anxiety, depression, overeating, insomnia, oversleeping, high blood pressure, overwork, always being sick, always being tired, being overly nice—the list goes on. These consequences affect not only your life, but they interfere with your relationships with others—your spouse, your lover, your children, your friends. Now is the time to change the pattern, but please don’t try to do it in a vacuum. Let others be a part of this new growth.

Recovery is the ability to tolerate feelings without the need to medicate or engage in other self-defeating behaviors.

Daughters of the Bottle

until i was twenty-two i didn’t think anyone else had a drunk for a mother then i met lori joannie and susan i recognized them immediately by their stay away smiles they were leaders in their work competent imposters like me who would say they were sorry if somebody bumped into them on a crowded street i call on them once in a while they always come children of alcoholics always do.

Jane

Breaking the Don’t Trust Rule

When you grow up not being able to trust the most significant people in your life it is difficult to trust others. At the same time it is possible there were trustworthy people at moments or possibly even throughout your growing-up years. The following exercises will help you begin to explore the issue of trust.

On a continuum from one to ten, one being totally non-trusting of people to ten, which is trusting everyone, where would you place yourself today.

Circle the answer to the following sentence stem:

“In my growing-up years, I could trust my …” If there was more than one, be specific with the name.

Father |

Brother |

Mother |

Sister |

Stepparent |

Friend |

Grandparent |

Other: _______________ |

When completed, for those you circled write a few sentences as to what it was about them made them trustworthy.

Complete the sentence:

Today I struggle with trusting people because …

The opposite side of the continuum is that sometimes in a search for love and acceptance adult children trust and put faith in people who are not honest and not reliable. If you identify, describe.

When you have become accustomed to only trusting yourself it can be difficult to be trusting of others. Yet there is a void in this one-sided approach to life. Make a list, even if short, of the benefits to trusting others.

As much as you may not think you trust others, it is very possible there are people in your life that you trust in certain ways. You don’t have to think of trust as an all-or-nothing attribute, there are people you would trust in some areas but not others. There are people who are trustworthy at certain times but not others. You do need to discriminate the ways in which and with whom you are trusting. There may be certain people at work you trust to help you out with specific projects. There may be a neighbor you trust to help you when your car is broken down and you need a ride. There may be a friend in the twelve-step community who you trust to hold a confidence. You trust your therapist to be respectful as he or she listens to you when you feel vulnerable.

Make a list of the situations and the people who you have found trustworthy.

Reshaping Roles

Responsible Child

The responsible child, otherwise known as the nine-year-old going on thirty-five, has probably come to find him- or herself as very organized and goal-oriented. The responsible child is adept at planning and manipulating others to get things accomplished, allowing him or her to be in a leadership position. He or she is often independent and self-reliant, capable of accomplishments and achievements. But because these accomplishments are made less out of choice and more out of a necessity to survive (emotionally, if not physically), there is usually a price paid for this early maturity.

For example: “As a result of being the little adult in my house, I didn’t have time to play baseball because I had to make dinner for my sisters.”

Complete the following:

As a result of being the little adult in my house, I didn’t have time to

_______________________ because __________________________.

As a result of being the little adult in my house, I didn’t have time to

_______________________ because __________________________.

As a result of being the little adult in my house, I didn’t have time to

_______________________ because __________________________.

As a result of being the little adult in my house, I didn’t have time to

_______________________ because __________________________.

For the person who has the ability to accomplish a great deal, the issue of control often creates problem areas in adult life. Accompanying a strong need to be in control is an extreme fear of being totally out of control, particularly with feelings. As Sue said, “If I permitted myself to throw one plate out of frustration, there would be nothing stopping me from throwing thirty!”

Because so much of life has been lived in extremes, you feel as if you are in control or out of control. You don’t know about some control. View it as impossible as being a little bit pregnant. Perceiving control to be an all-or-nothing experience, of course you don’t want to give it up. It once protected you. Giving up control is frightening because it has been vital to your safety. Control of the external forces in the environment is a survival mechanism. It is self-protection. It may be what allowed you to make sense out of your life. Controlling behavior was an attempt to bring order and consistency into inconsistent and unpredictable family situations. It is a defense against shame. Feeling in control gives a sense of power when overwhelmed by powerlessness, helplessness, and fear. Giving up control as an adult is difficult when up to this point in life it has been of great value.

• Sit back in a comfortable seat and relax. Breathe deeply.

• Uncross your legs and arms. Gently close your eyes and reflect back in time to your growing-up years.

• Recognizing how you exerted control externally or internally, finish this sentence:

Giving up control in my family would have meant ___________.

Giving up control in my family would have meant ___________.

Giving up control in my family would have meant ___________.

Giving up control in my family would have meant ___________.

Giving up control in my family would have meant ___________.

If you have difficulty with this exercise, another way to benefit from it is to describe the controlling behavior. Remember, controlling behavior was developed to protect you, so don’t be judgmental.

For example:

Not taking care of my mother would have meant

_________________________________________________________ .

—or—

Not doing the grocery shopping would have meant

_________________________________________________________ .

—or—

Not holding in my feelings would have meant

_________________________________________________________ .

Repeating these sentences allows you to access a deeper level of honesty. Now ask yourself if control means the same thing to you today.

As you become aware of the frightening connotation that the issue of control has, it is equally important to remind yourself of the positive aspects that come with letting go of some control. It is in giving up some control that you genuinely become empowered.

In asking those in recovery to name what they experienced as they let go of control they responded:

Peace, serenity. |

Spontaneity. |

Relaxation. |

Creativity. |

Ability to listen to others. |

Fun, play. |

Ability to listen to myself. |

Energy. |

Trust in myself. |

My present feelings. |

Lack of fear. |

Intimacy with self and others. |

These are the rewards, the promises of recovery.

As you reshape your life, you can retain pride in your ability to accomplish, but you also need to develop a greater sense of spontaneity and a greater ability to interact with others in a less rigid manner. You will be able to give up some areas of control only after you learn to identify your feelings and express these feelings in a manner that feels safe to you.

Adjuster

The adjusting child finds it easier not to question, think about, nor respond in any way to what was occurring in his or her life. Adjusters do not attempt to change, prevent, or alleviate any situations. They simply adjust to what they are told, often by detaching themselves emotionally, physically, and socially as much as is possible.

While it is easier to survive the frequent confusion and hurt of a dysfunctional home through adjusting, there are many negative consequences in adult life.

Example: “As a result of adjusting/detaching, I got into a lot of strange situations because I didn’t stop to think.”

Complete the following:

As a result of adjusting/detaching, I ____________________________

_________________________________________________________

because __________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________ .

As a result of adjusting/detaching, I

_________________________________________________________

because __________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________ .

As a result of adjusting/detaching, I

_________________________________________________________

because __________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________ .

As a result of adjusting/detaching, I

_________________________________________________________

because __________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________ .

The children who are more detached, possibly more nondescript than the responsible, placating, or acting-out children, are the adjusters. They need to take a look at how they feel about themselves. Adjusters have operated on the premise that life is easier if you don’t draw attention to yourself. They need to give themselves new messages that communicate that they are important people, and they deserve attention because they are important, they have value. Adjusters have many feelings that they have not had the opportunity to examine and feelings that they have not had the opportunity to share with others.

Adjusting adults continue to survive usually by living their lives in a very malleable fashion. They need to recognize that at times it is healthier and more satisfying to be less flexible. Because adjusters make very few waves for other people, they have no sense of direction for themselves. They lack purpose or a feeling of fulfillment. It is like always just being along for the ride—one feels a sense of movement, yet often travels only in circles.

One adult child revealed that her husband decided to move five times, taking her to five states, in the first four years of their marriage. She said she didn’t realize she could have discouraged any of the moves and, in fact, could have refused to go. She said she always did what he wanted. In retrospect, her adjusting was not good for her husband or for their relationship. If you are such an adjusting adult, you need daily practice in identifying the power you have in your life. Here is a four-part exercise that will help you do just that.

Part 1. At the beginning of each day, write down at least five options you have that day.

For example:

1. I choose whether or not I eat breakfast.

2. I choose where I buy gas for the car.

3. I choose whom I sit with at lunch.

4. I choose which television show I watch.

5. I choose the time I go to bed.

Recognize that these five options are certainly not major decisions, but in the beginning, it is wise to start with the small areas of daily life one can change. This exercise should be done consistently for a period of one week.

Part 2. Continue this exercise for a second week, listing ten choices that can be made on a daily basis. The goal of this exercise is to teach you to acknowledge your power in making choices. By the third or fourth day, you will begin to feel the power.

Part 3. After following through with Part 2, practice on a daily basis making notes of existing options that were not acted upon. List three per day. Continue this part of the exercise for one week.

For example:

1. I did not speak up when I was shortchanged $1.60 at the grocery store.

2. I allowed my daughter to use the car for the evening when I wanted to use it.

3. I didn’t tell my friends I disliked Japanese food when they suggested we eat at a sushi restaurant for my birthday.

The purpose of Part 3 is to recognize situations in which you did not act on your power.

Part 4. After each day’s documentation, make a log of what could be done differently should the situation occur again. Even if you do not take that different action, list a few alternative responses. Should other alternatives not come to mind, another person—a friend, a therapist, someone who you respect—may be able to recommend an option.

Practice Parts 3 and 4 together for another week. They can be repeated as often as you feel the need. Discuss this process with another, share the fun of having so many choices, and allow yourself to feel some pride in this new awareness.

If you are an adjuster who is attempting to change, watch for certain clues. Should you begin to experience boredom, depression, or a sense of helplessness, it is time to become reacquainted with your power and options. Practice the previous exercise again.

Placater

The placater, otherwise known as the household social worker or caretaker, is the child busy taking care of everyone else’s emotional needs. This may be the young girl who perceives her sister’s embarrassment when Mom shows up at a school open house drunk and will do whatever is necessary to take the embarrassment away This may be a boy assisting his brother in not feeling the disappointment of Dad not showing up at a ball game. This is the child who intervenes and assures that his siblings are not too frightened after there has been a screaming scene between their parents. This is a warm, sensitive, listening, caring young person who shows a tremendous capacity to help others feel better. For the placater, survival was taking away the fears, sadness, and guilt of others. Survival was giving one’s time, energy, and empathy.

But as adults, people who have spent years taking care of others begin to “pay a price” for the “imbalance of focus.” It is most likely that there were things that were not learned.

Example: “As a result of being the household social worker, I didn’t have time to tell anyone my problems because I was too busy assisting in solving other people’s problems.”

Complete the following:

As a result of being the household social worker, I didn’t have time to

_________________________________________________________

because __________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________ .

As a result of being the household social worker, I didn’t have time to

_________________________________________________________

because __________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________ .

As a result of being the household social worker, I didn’t have time to

_________________________________________________________

because __________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________ .

As a result of being the household social worker, I didn’t have time to

_________________________________________________________

because __________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________ .

For adult children who spend so much time taking care of other people’s needs, it is important to understand the word selfish. They have perfected the inability to give to themselves or consider their own needs. The placater’s role is always to attend to the feelings and wants of another. As adult placaters proceed in recovery, it is natural for them to feel guilty for focusing on themselves.

When I decide to put myself first for a change, I feel very guilty and have trouble differentiating between putting myself first and being selfish.

Remember, you are learning how to give to yourself and that is not bad. In order to be willing to give to yourself, it is vital to look at old messages that may need to be changed. New messages may be:

• I don’t have to take care of everyone else.

• I have choices about how I respond to people.

• My needs are important.

• I have feelings; I’m scared; I am angry.

• It is okay to put my own well-being first.

• Some situations can be resolved without my being involved.

• Others can lend support to those who need it when I am not willing to be available.

• I’m not guilty because others feel bad.

This should only be the beginning of a list of new messages. To the adult placater, make a list of new messages. On a daily basis for a minimum of a month, read and reread these messages aloud to yourself.

You will feel some of the old guilt for a while, but it will be mixed with a new sensation—that of excitement along with a sense of aliveness. I believe in people giving themselves credit and being their own best friend so do not be embarrassed about validating yourself.

Fifty-four-year-old Maureen said she spent her life trying to be everybody’s good little girl. She walked a very narrow line, afraid to do anything that might cause anyone’s disapproval. “Slowly, I have learned it is much more important for me to consider my own needs and feelings, and how important it is for me to act on them.” This is the type of freedom all adult children can attain. Maureen knows the process is slow. It is not easy to give up fears and try new behaviors. But, it is possible!

If you think you fit into the placater’s role, examine how you give. On a daily basis, document all the little things you do for people. Itemize each one. After you have read your list of anywhere from fifty to a hundred items, are you tired? Of course you are tired. Where will you find the energy to give to yourself? The answer—you won’t. Ask yourself if each of these placating acts was absolutely necessary. Could you have backed off a little? As you attempt to back off on giving, you need to start work on being able to receive. All true placaters need to work on receiving.

Ask yourself about your capacity to receive. Do you “yes, but …” when you are complimented? Do you change the subject when you are commended? Are you embarrassed or do you feel awkward when you receive a gift? Can you enjoy the moment? You may need to give yourself new messages regarding receiving:

• I deserve to be given a thank-you.

• I can enjoy being the recipient of praise.

• I will take time to hear my praise, smile, and soak it in.

For a minimum of two weeks, pay strict attention to receiving. Practice your new messages.

Mascot

Humor and wit are valuable characteristics. Everyone appreciates laughter and the relief and distraction it can provide at times. But when it is the predominant way of being, the primary coping mechanism, you don’t get to learn or experience things that would be helpful to you.

For example, “As a result of being the family clown, I didn’t have time to pay attention at school.”

Complete the following:

As a result of my mascot/clown role, I didn’t have time to

_________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________ .

As a result of my mascot/clown role, I didn’t have time to

_________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________ .

As a result of my mascot/clown role, I didn’t have time to

_________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________ .

Another sentence stem exercise that may be of value for insight:

My humor covered my ______________________________________.

My humor covered my ______________________________________.

My humor covered my ______________________________________.

Or

Letting go of my humor would have meant ______________________.

Letting go of my humor would have meant ______________________.

Letting go of my humor would have meant ______________________.

Acting-Out Child

Acting-out children are confused and scared and act out their confusion in ways that get them a lot of negative attention. Some kids became very angry at a young age. They get into trouble at home, school, and often on the streets. These are kids screaming, “There’s something wrong here!” These are kids who didn’t find survivorship in the other three roles.

Example: “As a result of my acting-out behavior, I didn’t have time to pay attention at school.”

Complete the following:

As a result of my acting-out behavior, I didn’t have time to

_________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________ .

As a result of my acting-out behavior, I didn’t have time to

_________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________ .

As a result of my acting-out behavior, I didn’t have time to

_________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________ .

As a result of my acting-out behavior, I didn’t have time to

_________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________ .

It is easy to scapegoat yourself for being in this role, yet creativity, flexibility, honesty, and humor are but a few of the strengths often shown by people who adopted this stance. Make a list of characteristics you value about yourself. If they are not taken to an extreme, they are most likely strengths.

Adult Roles

Today as an adult I am still (check the appropriate boxes):

Overly responsible

Overly responsible

Placating

Placating

Adjusting

Adjusting

Using humor as a defense

Using humor as a defense

Acting out negatively

Acting out negatively

Other ____________________________________________

Other ____________________________________________

As a result, I still haven’t learned

_________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________ .

It is important for me to take the time to (be specific)

_________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________ .

Letter of Thanks

It is important to honor your coping mechanisms; they were critical to your survivorship. Recovery doesn’t involve being critical of what you needed to do to protect yourself while you were growing up.

Whatever your predominant role was, write a letter to it thanking it for how it was helpful at the time.

Then go on to tell that role how it ultimately got in your way or caused you problems as an adult.

Dear (role),

I want to thank you for _____________________________ .

But there were things I didn’t get to do or didn’t get to learn because of you.

I didn’t __________________________________________

________________________________________________

________________________________________________

_______________________________________________ .

Honoring the Strengths of the Roles

Review the strengths and vulnerabilities of the roles you identify with and note the personal strengths that you want to maintain.

Establishing Boundaries

Circle the boundary violations that you experienced growing up.

• Parents do not view you as separate beings from themselves and want you to meet their needs.

• Parents did not take responsibility for their feelings, thoughts, and behaviors but expected you to take responsibility for them.

• Parents’ self-esteem is derived totally through your behavior.

• You were treated as a peer with no parent/child distinction.

• Parents expect you to fulfill their dreams.

• Parents objectify you as a possession, as a belonging versus as your own human entity with rights and desires

By establishing boundaries and setting limits, you will begin to find the freedom of using the words “No” and “Yes.” It was not safe to say no as a child. Without the freedom to say no, yes was said with tremendous fear and helplessness or out of a desperate need for approval and love. Recovery means recognizing the ability to say no is a friend to protect you. You have the power and right to say no and yes. You will find that yes is a gift that is offered freely rather than out of fear or the need for approval. Recognize that by saying no, you are actually saying yes to yourself.

Make a list of people you would like to set better boundaries with, identify what that boundary would look or sound like. Note if you need support and where you can get that support.

Names |

Boundary |

Support Source |

1. __________________ |

_________________ |

_________________ |

2. __________________ |

_________________ |

_________________ |

3. __________________ |

_________________ |

_________________ |

4. __________________ |

_________________ |

_________________ |

5. __________________ |

_________________ |

_________________ |

Start with the one who feels most safe to you and one you think you will be most successful.

Getting to Know Your Trauma

Circle the traumas you experienced on a chronic basis:

• Severe criticism and blaming.

• Verbal abuse.

• Broken promises.

• Lying.

• Unpredictability.

• Rage.

• Harsh or even cruel forms of punishment.

• Being forced into physically dangerous situations such as being in a vehicle with an impaired driver.

• Parental indifference to your needs and wants.

• Emotional unavailability, not showing love and concern.

• Unrealistic expectations.

• Disapproval is aimed at your entire being, your identity, your worth, and value rather than a particular behavior.

Trauma Timeline

To get another visual, you can pull the trauma, roles, and shame-based beliefs into one piece of work.

You will need a large piece of paper and different colored pencils. Draw a line across the page. On the left write birth, and to the far right end note your age today. See below.

Birth _______________________________________________ Today

Along the line, begin by noting the traumas you experienced (you may want to refer to the traumas identified in the previous exercise and/or those discussed in Chapter Five). If it is chronic such as rejection for your sexual orientation or unrealistic expectations, note the age you first experienced it and then draw a continuous line that shows how long it continued.

With a different color pencil, note approximate age when your predominant family role began to show itself. Then note if that role ever shifted in your growing-up years.

Under each trauma, identify the beliefs you internalized about yourself.

For example:

I am a bad person. I hate myself. Nothing I do is okay.

Taking Risks

List five risks you have taken in the past that you feel good about. They could be risks at work, in your family, or as a part of a love relationship. Name the risk. What did you fear? What did you do, say, or think to get yourself to push through the fear and take the risk?

Risk |

Fear |

Push |

1. __________________ |

_________________ |

_________________ |

2. __________________ |

_________________ |

_________________ |

3. __________________ |

_________________ |

_________________ |

4. __________________ |

_________________ |

_________________ |

5. __________________ |

_________________ |

_________________ |

Many people attempting to make changes sometimes fear they will go to the other extreme. While the internal experience may feel extreme, the behavior is usually not. What often feels internally like the roar of a lion is only a peep. It’s just that for you it is alien, and it feels intense. There is a saying that I have appreciated over the years: “Feel the fear and do it anyway.” You need to push through the fear. And you have begun to do that. You are breaking the rules of Don’t Talk, Don’t Feel, and Don’t Trust. Recovery is occurring.