CHAPTER EIGHT

The Child within the Home

Children are not immune from the effects of addiction. They live with it and therefore need to understand it. First and foremost they need to know the 7 Cs.

The Seven “C”s

I didn’t CAUSE it.

I can’t CONTROL it.

I can’t CURE it, but

I can help take CARE of myself by

COMMUNICATING my feelings,

Making healthy CHOICES,

and

CELEBRATING me.

© Jerry Moe, MA

I Didn’t CAUSE It

Children often blame themselves for family problems, sometimes they are told it is their fault by family members. When children experience trauma in their lives and no one explains it to them in an age-appropriate way, they make up a story for it all to make sense. They are often not only dealing with addiction but also other problems that may be associated with it such as divorce, domestic violence, depression, incarceration. Children need to hear that they did not cause their parents addiction; they did not cause their parent’s depression; they are not responsible for their parents not being together. They are not responsible for the problems their parents are experiencing. And they need to hear this over and over and over.

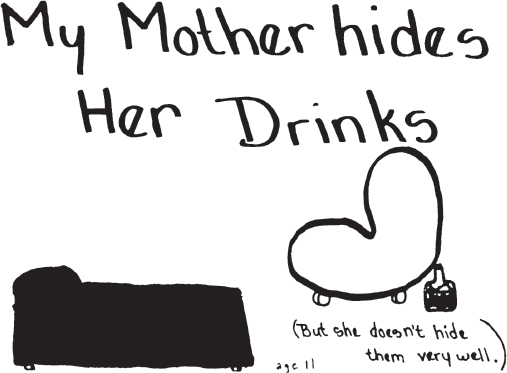

I Can’t CONTROL It

Children may take steps to stop a parent’s drinking or using. They vigorously attempt to improve things in their families. Some pour alcohol down the drain and throw away drugs they find hidden in the house. Others take on parental responsibilities that often include caring for their brothers and sisters. Some play the peacemaker during times of conflict. They may try to be perfect in all they do hoping all of these behaviors will help the problems go away. When this does not work they simply try harder.

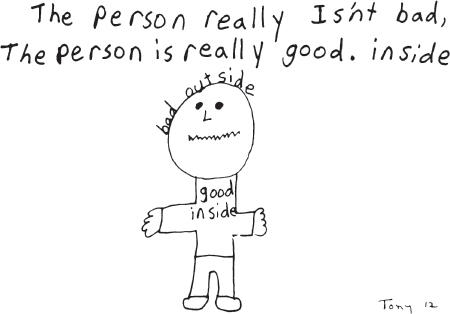

It is vital to teach children that addiction is a disease. Once the person who is addicted starts drinking or using, he or she cannot stop. Children understand the words “stuck,” “being hooked,” or “trapped.” It is also essential to explain that people suffering from addiction are not bad. Yet when they are stuck, hooked, and trapped, they sometimes do bad things like breaking promises, not playing with their kids, or maybe even not coming home. It is important to help children separate the people they love from the disease that consumes their parent.

Understanding addiction also reduces their anxiety by making the unexpected predictable. Knowing that the family is responding to a sickness allows the child to remain guilt-free because an illness is not something they can cause or control. When children realize a parent is addicted, it gives them the freedom to filter and evaluate the information passed along. Most significantly, it gives a name to their experience, and it says they aren’t at fault. It gives them a voice with which to talk about their experiences.

Children who grow up never having shared their closest thoughts or feelings with even their very best friend, live a very lonely, isolated way of life. This loneliness continues into adulthood because no one understood their trauma or was willing to take the time to talk to them. When the dysfunctional family rules are broken, children have a foundation for understanding what they are experiencing.

If the concepts of addiction are explained in age-appropriate language they understand, children of all ages can comprehend it. Adults need to talk openly and provide children with access to resources that reinforce healthy messages.

Disease of Addiction

It is advisable to ask children how they would describe addiction and what traits constitute being an alcoholic or addict. Children have undoubtedly heard the stories from a friend, a family member, or through the media that are often inaccurate portrayals filled with judgment and stigma. Asking the child for his or her perception offers the helping person an opportunity to gauge, clarify, or validate knowledge.

Addiction is not a disease caused by a germ or virus, as are many others, but it is an illness nonetheless. People do not choose to become addicted and all the willpower in the world will not control or cure addiction. Children prior to the ages of nine and ten do not need a lot of explanation. They are more accepting of it being a disease with both phyiscal and psychological ramifications. It makes sense to them. They more readily accept the analogy of being stuck to something and not being able to get off, such as having gum stuck in your hair and needing help to get it out; a fish stuck on a hook and needing a person to unhook it; a bee stuck to a flower. Often they are told a parent is allergic to alcohol or other drugs and the allergy makes the brain work differently and the parent does things he or she wouldn’t do otherwise. The only way to stop is to totally stop using altogether. But because the brain is confused, the parent needs help from others to stop. Children see the personality changes and also see the inability to stop once started. With young children, this conversation is more likely to be brief and more general.

As young people move into their adolescent and adult years they are not so willing to accept the disease model as an answer for why or how their parent behaves. They are often angry and perceive the disease model as a cop out. It’s still helpful for them to be given an education about addiction. It will not be lost on them. With this older child it is also helpful to discuss the role denial played in the disease, describe the progression of losing control, how the addict is responsible for relapses and, if experienced, what was learned from the relapse. In the long run it will be changing behaviors that will heal relationships with their children of all ages.

Blackouts

Blackouts are periods of amnesia, varying in duration from minutes to several hours or, for some people, several days. It is a period of time when a person is under the influence of alcohol or other drugs—particularly benzodiazepines and barbiturates—yet is awake and interacting in the environment, possibly even socially engaged. However, the memory of the experience is not recorded in the brain and therefore the person is unable to remember what happened. Not all alcoholics or addicts will experience blackouts but should they occur they are very confusing and result in a lot of anxiety and anger.

Imagine a Friday night when Dad doesn’t come home for dinner and still isn’t home when everyone has gone to bed. When he finally does arrive, he makes a lot of noise and argues with his thirteen-year-old daughter, whom he meets in the hallway as she heads for the bathroom. Dad then proceeds to wake Mom and the two of them argue loudly for several hours in their bedroom. All three kids listen to the arguing throughout the night. The next day everyone acts as if none of that happened. Actually, the father doesn’t know what happened. The last thing he remembers about Friday night is drinking with his friends and anticipating that his wife would be angry because he was late for dinner. His recollection of the night stops somewhere in the early evening. He doesn’t remember when or even how he got home, arguing with his daughter, or with his wife. He does know he feels lousy and that his kids are acting skittish and his wife is angry but not talking. All of the children show some anxiety around him and are very apprehensive. Rather than risk knowing the reality of the previous night, after all that would confront his drinking behavior, he would feel fear, guilt, and shame, so he simply acts placating of everyone the rest of the day. No one talks about the real issues—Dad’s behavior the night before, the confusion, the fear, and the disappointment. In a family already fragmented, more distance and misunderstanding are created.

Children are often hurt about events the addicted person doesn’t even recall. It’s extremely crazymaking. And seldom are there any related discussions, as the addicted person feels guilt and fear should he or she pursue finding out about those events. The partner feels confusion as the children do as well as feeling angry and hopeless. The children are just accumulating another painful experience leaving them with more fear, sadness, embarrassment and, at the least, confusion.

Some children may suspect that their parent, when drinking or using, actually does not remember a period of time. Other children who do not understand what is happening with their parent have an even greater sense of confusion and craziness. Whether or not children recognize when blackouts occur, they need to have some information and an explanation that validates their own experience and allows them to have a better understanding of their parent’s behavior.

An analogy that may be useful is describing a blackout as a switch turning off one part of the brain and nothing is allowed to enter that part. When the switch comes back on, the part of the brain that was turned off remembers nothing that occurred during the time it was switched off.

Personality Changes

The Jekyll-and-Hyde personality is common in homes riddled with addiction. The alcoholic parent, when on the rising side of the blood alcohol curve often becomes more expansive in attitude, is more warm, welcoming, loving, generous, and then when on the downward side they are often are more agitated. Anyone who gets in the way of their using are targets for their agitation.

Drugs and alcohol impact volatility of emotions and influence lack of impulse control, which changes personality. The thinking part of the brain goes to sleep while the emotional part of the brain has begun to take over, the part that says, “I want what I want when I want it and don’t get in my way.”

Children also describe the nonaddicted parent as demonstrating personality changes. “We leave for school in the morning and mom is all nice and loving. When we come home she snaps at us the minute we come through the door. Then she disappears to suddenly be right back in the living room and is really angry. She tells us we are slobs, yelling that we need to get our homework done, that we aren’t grateful enough. We don’t know what was happening, she gets like that a lot. But mostly she is really nice to us. She makes us things, likes to be around us. It’s so confusing.” The codependent parent’s preoccupation with the addict and the fluctuation of feelings associated creates unpredictability and irrational responses.

Broken Promises

Broken promises are a common reality for children living with addiction. They are often told they will be going someplace or a parent will attend a school event or they will be given something, only to have the parent not follow through. This usually occurs with no accountability or apology. It is important that children know their feelings are valid and that promises are broken because of the parent’s addiction not because of a lack of caring or loving. Sadly, the preoccupation with drinking or using becomes the addict’s number one priority. All else is secondary.

Denial

Denial occurs when people pretend things are different than they really are. In order to protect their addiction, addicts deny how much they drink or use and the impact this has on others. If the addicted person is not in denial he or she is faced with overwhelming shame, guilt, powerlessness, fear and hopelessness. That then leads back to denial.

Family members also deny. The partner and children deny for many of the same reasons. If they don’t deny, the truth is too emotionally overwhelming. Without a sense of why, without direction, without hope, it’s easier to move into denial. Children don’t just deny what they see, they also deny their feelings, say things like “It didn’t hurt,” when it did; “I wasn’t angry,” when they were; “I wasn’t embarrassed,” when they were; “He didn’t know what he was doing,” when he did.

Multiple Addictions

Often by the time a person seeks recovery he or she is addicted to more than one behavior or substance. The family may or may not know that. The following analogies are helpful in explaining multiple addictive disorders.

If there are two or more addictions occurring at the same time, think of it as a wagon being pulled by a team of horses. Sometimes one horse pulls the wagon, representing a single addiction, but it could be two, three, or even four horses.

Another way to think of this is to get a car started you have to use the ignition. One addiction is the key in the ignition, the second addiction is the fuel in the tank.

Relapse

Relapses are not unusual in that they occur in most progressive diseases. In a disease such as cancer, there are times when the cancer appears to be in remission and is not progressing. Then, it may reappear again and the patient is said to have had a relapse. When someone has pneumonia and recovers, they may become sick again, suffering a relapse. Relapse is a term that needs to be discussed if a parent attempts to get clean and sober. Many parents ask, “Why worry the child?” The reality is the child is already worried. It is also possible he or she has already witnessed a relapse and are acutely aware it could happen again. To not discuss relapse is to stay in denial about its possibility.

Nine-year-old Melody described most eloquently a definition of relapse.

A relapse is when you stop drinking and then you start again. It’s like when you have a cold and you think it is gone. Then you go out in the rain and your cold comes back.

It’s important for children to understand they don’t cause relapses. When the father relapses shortly after his sixteen-year-old son wrecked the family car, dad is responsible for the relapse. The father must learn to cope with such problems or uncomfortable feelings, without reaching for his drug. The addict is not responsible for having the disease but is responsible his or her recovery.

I Can’t CURE It

A child can’t cure addiction. The addicted person and the other parent must get help for themselves. This can include going to a treatment program, working with a counselor, attending self-help meetings, and/or returning to their faith. People can find joy, peace, and serenity if they stay committed to ongoing recovery practices.

Addiction is chronic, and the abstinence from the drug or the self-defeating behavior is the first step to recovery. People find if they stay in recovery practice it helps them to be honest with themselves (the psychological aspect of the disease), it helps them avoid slipping into rationalization and denial. It allows them to stay accountable for their own behavior. And it allows them to give back to others seeking recovery, which fills a spiritual void. As said by one twelve-step member, “Meetings keep me vigilant and help me not become complacent about this disease that is just one drink or one toke or one snort away. Meetings help me like myself. Going to meetings is like putting money into a savings account and it earns interest. Going to meetings is my ‘recovery interest.’”

Most importantly, it is the responsibility of the adult to get the help they need, it’s the children’s job to be children.

MY DADDY

I woke up one morning and he was gone he was gone my daddy and he would never be home again.

He was gone my daddy

the one who always showed his love the one who always understood, when she never would!

The one who always brushed my hair, combed and put ribbons in my hair

he was the one who picked me up when I fell and skinned my knee. Oh my daddy, my daddy.

I still remember all the things he taught me—but he was gone. And I was too young to understand he said they just didn’t get along.

I hardly ever saw him,

my daddy who was always there, my daddy who always cared. It seemed he just didn’t have time for me. But that was also ten years ago and I think

now I understand.

But there’s still one question that remains. And that’s—Why

Oh Lord, did this have to happen to me???

Why did my daddy have to go, and leave me all alone?

She says he’s alcoholic, a person who has a disease and needs

help … But can only get it if he wants it.

He must admit to himself that he is sick and needs help. he

knows all this now and I do too.

Now it’s too late, he’s already gone.

He’s remarried now and he has a new little princess who he

brushes, combs, and puts ribbons in her hair. But Lord this is

so unfair!!!

He is my daddy and he needs help!!!

But I feel so helpless Lord because

it seems he still doesn’t have time for me. I love my daddy,

whom I hardly ever see.

And even more when I think about

how much he must Love Me—MY DADDY

—Renee, age 16

I Can Help Take CARE of Myself

Mindfulness and grounding practices are wonderful forms of self-care and have the added benefit of lessening trauma responses as they calm the emotional part of the brain. Such practices are forms of crafts, such as bead work, pottery, knitting, crocheting, all types of art. Engaging in nature and spending time with animals are also nurturing. Whether it is structured or spontaneous, singing and dancing can be calming and grounding. Reading is another way of taking care of yourself. Today there are apps and books available for young children to practice yoga, breathing, and guided imagery that are all helpful to keep kids present in the moment and to cope with the stress they are subject to.

Self-care also comes in the form of healthy boundaries. When children understand they don’t cause the family stress nor are they in a position to cure it, they are in a better position to have healthier boundaries. A healthy boundary is often demonstrated by behavior and is not necessarily verbalized. Knowing how and when to remove yourself from an uncomfortable or unsafe situation is an important boundary, such as removing yourself from the potential line of fire when the verbal abuse begins. Where can you go that is safe? What can you do to distract yourself? When you are able to demonstrate problem-solving skills and engage in healthy choices those are acts of self-care. The ability to communicate feelings, build connections with others, and celebrate yourself are also acts of self-care.

COMMUNICATING My Feelings

Children raised with addiction experience loss on a chronic basis. When children experience loss they enter a grief process, one similar to the grief processes other people experience when they lose a loved one due to death or when a loved one becomes incapacitated because of a serious illness.

The first state of grief is disbelief or denying the loss has really occurred. The disbelief may be nature’s way of helping a person through this stage by deadening the pain, by giving a person time to absorb the facts. Unfortunately, with addiction, this grief process is much slower, occurring over a much longer time and in a much more subtle way. As a result, family members are often in a state of disbelief for a lengthy time.

With addiction, as time passes and the truth becomes more evident, the family begins to experience terror—the terror of the reality that a loved one is an addict. Usually, the next emotion following the terror is anger. “If you (the addict) really love me, how can you be like this?” Family members often feel guilt and each family member believes that in some way he or she is responsible. A son believes, “Maybe if I hadn’t talked back, Dad wouldn’t drink so much or be so angry all the time.” A wife believes, “If I were a better wife, my husband wouldn’t be sick.” A husband believes, “Maybe if I had been home more …” Bargaining is practiced by family members when they elicit promises from the addict to control or stop his or her using. At other times, bargaining is self-imposed, “If I behave this way, maybe Mom will respond another way.” For many children, bargaining is through prayer, “Please God, keep my mom and dad together. Don’t let them fight so much. I promise I will be real good.”

Finally, family members feel desperation and despair. They each feel alone with the problem. They feel all these terrible things are unique in their lives, that no one else could possibly understand their pain. They despair that there are no answers or solutions to the guilt they carry. This process and these feelings are common to all persons affected by addiction.

Families who try to run away from their feelings suffer longer. Often, they never recover from their grief, and it becomes a long-lasting depression. Families who face loss and the related feelings, become stronger and are able to begin growing, living full and satisfying lives.

A child can survive a family crisis as long as the child is told the truth and allowed to share the natural sequence of feelings experienced when he or she suffers. In addictive families, everyone suffers, and everyone suffers very much alone. Children often suffer from loneliness, fear, anger, and a multitude of other feelings that they have no way of understanding and they do not have the ability to express this lack of understanding.

Although the child may receive help to understand addiction, intellectual understanding will not erase the multitude of intense feelings they experience. Children can understand and feel at the same time. It is important for someone to explain that their feelings are perfectly normal. Children need to be able to say, “I was so embarrassed. I know she is sick, but she still embarrasses me and it hurts!” Or, “I’m sad because Mom is like she is. But, I’m also really angry, and I don’t understand why she won’t go for help!” All of these feelings are valid. Children need to know others will validate and listen to their feelings.

Sadness

Crying is a natural release of the emotion of sadness. Crying is difficult for many people. Those in addicted families usually do one of two things: they learn how not to cry or cry alone, silently.

Before a child can cry and feel okay about it, the child needs to be given healthy messages regarding all feelings. Children need to hear “It’s okay to cry.” “Crying can help you feel better.” Other messages, such as “Boys shouldn’t cry” and “Don’t be a crybaby,” need to be countered. Children also need models who can demonstrate that crying is not weak or shameful. Children need to hear that when adults hurt they, too, cry. And that when family members show each other their tears, it is often a time in which they can feel closer to each other. Aside from giving permission to cry, children need support to share their feelings with others. Ask children who they could tell about the times when they cry? Who do they trust enough to confide in? Who in the family do they trust to ask for comfort at such times? This is an important discussion.

I once worked with a brother and sister, six-year-old Chuck and nine-year-old Melody. Chuck was very open about not trusting his mother and his helplessness regarding her drinking. He talked about worrying a lot, and how when he cried and Melody would tell him to shut up. She would talk louder when he was speaking and would call him a crybaby. She was prepared to do just about anything she could to keep Chuck from crying and showing his feelings. Though there was only three years difference in their ages, Chuck and Melody were in different phases of handling their stress. It is important for adults to be aware of these varying stages of denial among children and how children interfere with or are supportive of each other’s expressions of feelings. One child may be more open to expression of tears, while another is obviously angry; still another child appears more emotionally disconnected. Each child needs to have access to all of their feelings and have healthy avenues of expression.

Fear

While fear is a natural emotion for all children, it is, unfortunately, pervasive in an addictive family. A parent’s drinking or using results in a lot of tension in the home, and it’s important a child’s fears are acknowledged and validated. Whether or not children express specific fears, parents, family, and friends need to validate that at times it is normal to be afraid. Many times, nothing can be done about what is creating the fear, yet acknowledging it can lessen the power. Expressing feelings develops closeness between parents and children and is helpful in decreasing the children’s feelings of being overwhelmed by the emotions kept inside. Emotions become so much more powerful when they are not outwardly expressed. Keeping feelings hidden can cause a great deal more pain than is necessary.

Anger

Everyone experiences anger. Yet due to punishment, the possibility of rejection, or fear of abuse, many children are reticent to own or share their anger. It is extremely important for children to become aware of their frustrations and angers and then find ways to express them. Children’s anger is only problematic when it has been stored and appropriate ways of expression have not been introduced.

Ask children what happens when family members get angry. Their responses will guide you in supporting healthy behavior or countering unhealthy expressions of anger. When nine-year-old Mason was asked what people in his family do with anger, he said, “Dad leaves the house. Mom drinks. Tommy goes outside. I’m not really angry.” Mason was a very overweight young boy, and his description demonstrated how he had copied his mother’s pattern for coping with anger while his brother copied his father’s pattern. Two family members leave their anger behind, and two drink or eat to cope with it. None of them found a healthy way of coping with anger.

To feel safe in expressing anger, children need adults to help them discriminate where it is and is not safe to share those feelings. They need to know their anger will not cause them to lose their parent’s love. For many, expressing anger has come to mean “If I show you I’m angry with you, you will withdraw your love.” Children need to know what limits are placed on the expression of anger and what others perceive as appropriate responses to situations. They need to know their hurts and anger are important and should not be discounted. Children often discount problems in their own lives because they believe problems within the family take precedence over any personal conflicts occurring outside the home. “Who am I to talk about how angry I became at school today? There is already enough tension at home.” The messages learned are:

• What happened to me at school is not important.

• The feelings I have throughout the day are not important.

• I am not important.

Children need to have their feelings validated.

Guilt

Children assume they have the power to affect everything, when in truth, they have very little power in an addictive environment. “Dad was always screaming and hollering about us kids never doing anything right, so I assumed we had to be making him very unhappy and that was why he took off and didn’t come home.” Children need to know they do not cause someone to be addicted. Children need to be reassured that even if they behave in a way that upsets a parent their parent has many choices other than drinking or using to handle the situation. Remind them no one but the addict is responsible for the alcoholic/addict’s actions.

It is important for a child to be able to distinguish the difference between true and false guilt. As stated previously, true guilt is a feeling of regret or remorse for your own behavior. For example, a person is responsible for being late, lying, stealing, not following through on a commitment. False guilt is a feeling of remorse that come from believing you are responsible for someone else’s behavior and actions.

Devon is twenty-three years old. He recently attempted to take his own life, struggling with depression for a long time. He, his brothers, and his mother were all the recipients of his dad rages and verbal assaults. They were always being blamed for things; often called names. Devon never once talked back to his dad, never once tried to defend himself or his mom; he just accepted the abuse. He wanted to love his dad, but he was quietly becoming more and more angry. One day he had been bullied at school by some older boys, then came home to his dad’s bullying. That night, he flew into a rage, yelling at his father, and started hitting him in the chest. Devon told him he was a lousy father and hoped he would go away and never come back. He didn’t talk to his father the next couple days and then his father, while on a binge, got into a car accident; a passenger was killed and his father was sent to prison for the next several years. Devon felt that he “willed” his dad to get in that accident and has never forgiven himself. He has lived with this false guilt for over ten years. When you feel such futility, as Devon did, it is a normal response to wish that the person who creates so much pain would disappear, go away, and, yes, maybe even die. Instead of being able to be angry with his father and be sad for the relationship he may never have and for all the pain that has occurred, Devon implodes with guilt that is not his, fueling major depression that ultimately leads him to suicidality.

Love

Love consists of mutual respect, trust, and sharing. It is understandable for children to be confused about loving a parent who is frightening, unavailable, or inconsistent. Yet they learned early in childhood that they are expected to love and respect their parents. As a result, many children are ambivalent and confused about loving their parents.

Love frequently withstands a lot of inconsistent, painful parenting though. The love that is felt often relates to the experiences shared prior to the onset of addiction, as well as to the sober moments shared. Addicted parents are not under the influence all the time.

Remember, addiction is a process, the onset of which most often begins in young adulthood. This indicates that most parents begin raising their children prior to the addiction or in their early addictive years. When a person is in the early stages of addiction, the behavior may not be consistently disruptive to the family. The same is true for the nonaddicted parent. The codependent behavior was not necessarily typical of them in the early stages. They, too, were often more consistent and provided more quality time for the children. It is over time that nonaddicted parents become depressed, angry, rigid, or absent The love children feel was often internalized in those earlier years.

It is my bias that while we cannot make children love their parents, we can help them not to hate if we can provide more consistency in their lives, as well as educating them to better understand addiction and its effects on the entire family structure.

Learning to Feel

Children learn about feelings and what to do with them by modeling adults. The more healthy role models that are available, the greater the ability children have to adopt that healthy behavior and utilize positive avenues of expression. The more isolated the family becomes, the fewer options children have to learn from healthy adults. Children need access to healthy role models.

Children have to be helped to understand that feelings are transitory. One may feel intense hatred for a person, then, at another time, feel empathy and love. You may experience great tenderness one moment and only a few hours later feel enraged. Feelings change, and children will not be stuck with any one feeling forever.

They need to know it is possible to experience more than one feeling at a time. Love and hate, and sadness and anger can be felt together, as can happiness and sadness, fear and anxiety. There are numerous combinations. What’s important is that the adult accepts the child’s feelings. If adults can accept and validate children’s feelings of intense dislike, as well as anger, fear, and disappointment, then they can also help children to live lives free of guilt for having these feelings. We can help children work through these feelings and, hopefully, acquire a more loving acceptance of themselves.

Making Healthy CHOICES

A part of making healthy choices is learning it is okay to ask for help. Children can only do that though if they have identified safe people in their life. Safe people could be extended family members, neighbors, friends’ parents, school personnel ranging from coaches to teachers, to administrators, neighbors, etc.

Wendy needed to her mom to take her to an important school event but her mother was nearly passed out on the couch. Remembering she had learned about options at school, Wendy thought about her options: 1) not going; 2) going with a very impaired mother; 3) calling a friend and asking her mother to come and take her; 4) jogging to the event; or 5) calling her grandfather and asking him to take her. She called her grandfather. She knew he’d be more available than the friends’ mom and knew she could be honest with him. She didn’t want to be honest with the friends’ mom, it was too embarrassing and she had to focus on the event. She knew she wouldn’t get there if she jogged. She also knew her mom was too impaired to drive.

There are not any clear-cut satisfactory answers for such problems. All children need an adult, preferably a parent, to

• Offer them guidance and suggestions so children realize they have options.

• Protect them.

• Give them permission to protect themselves.

• Let them know it is okay to ask others for help.

Children can better handle problems and protect themselves when they have the time to discuss and think over potential situations. When they are briefed on possible situations, options identified, given positive messages about themselves, and believe an adult will support them, they will usually choose better options.

CELEBRATING Me

Every child is precious and deserves to be celebrated. Find ways to acknowledge, validate, and celebrate children. Acknowledge their problem-solving abilities. Acknowledge their creativity, talents, and personality attributes such as kindness and humor. Offer opportunities for them to show their strengths, be it on the playground, during visits to a friend’s home or the classroom. You don’t have to expect children to say thank you. They may even try to rebuff your feedback. Regardless, acknowledge, validate, and celebrate. It will make a difference.

Encourage Connections

Children grow up to be just like their parents or to have a variation of their parents’ dysfunction unless someone shows them a different way. It is important for children to have a connection to others who help them problem-solve so they aren’t problem-solving in a vacuum. They need someone who engages them in activities that increase their self-esteem. Being involved in extracurricular activities at school or church has proved to be of significant value in developing resiliency and strengths in response to a problematic life. Exposure to healthier ways of coping and relating and the opportunity to explore their individual talents is crucial for a child living in a troubled family. Every adult child can identify some one person who they believe made a positive difference in their life. That person did or said something that helped that child feel he or she was of value.

Tom’s involvement in high school sports was his time out from home, giving him relief, but also sports offered him a source of esteem. Ellie still sees her junior high school boyfriend’s parents. She considers them as having been surrogate parents who listened, validated her, and allowed her to just be a kid when she was with them in their home. Lew believes it was his uncle, whom he describes as a quiet man, who took time to allow Lew in his life. He allowed Lew to help with chores around the house, go on short vacations with his family, and showed up at Lew’s school events. The message Lew got was that he was of value to this uncle, that he was worthy. What can seem so little to the giver can make a tremendous difference to the receiver.

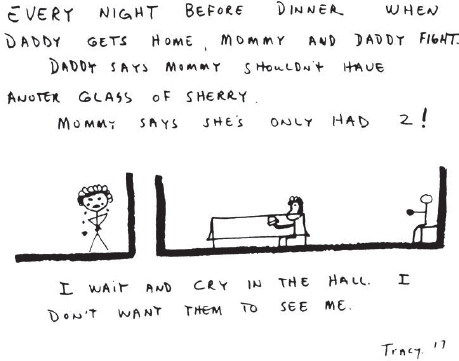

Create and Maintain Positive Family Rituals

Healthy family rituals create a sense of belonging offering children a sense of pride. All families have rituals, but sadly for children raised with addition, healthy rituals are often decimated, and unhealthy rituals manifested. In addictive families, meal times are often times to be feared or don’t exist. Bedtime is lonely. Rituals around holidays are ignored, dismissed, or are times of family scenes and trauma. Celebrations, be it birthdays, graduations or religious ceremonies, are times of great trepidation and unpredictability.

Building healthy rituals begins with identifying daily rituals (mealtimes, bedtime, after school time), and yearly rituals (birthdays and holidays) and then any other rituals that the family has created, (Saturday-runs to a yogurt store, service work on Sundays, etc.). What messages do these give the child? What can you do to reinforce a healthy ritual around the already existing ones, and what new ones can be incorporated? It is possible when children’s parents don’t live together that at least one parent can maintain healthy rituals. Sometimes, the rituals occur via extended family members. Whatever can be done to support this is most important.

Reshaping Roles

Reshaping roles is about attending to the emotional, mental, and behavioral deficits that result from the dysfunction within the family during a child’s developmental years. These voids include not learning to relax, not knowing how to rely on others, not knowing how to follow or not knowing how to lead, never allowing one’s own needs to be met, and the many other undeveloped coping mechanisms. Not only will these gaps create life-skill problems, but they may also predispose the children to marry addicts and/or engage in addictive disorders. The lack of healthy coping mechanisms often predisposes children to experience depression, anxiety, and relational problems.

When helping children understand addiction through talking about the real issues and teaching them to identify and express feelings while establishing healthy support networks, there is also a specific need to focus on reshaping roles.

The rigidity of the roles were adopted out of the severe need to bring consistency to a chaotic and unpredictable family system, to emotionally make sense of the moment. Children get to keep the strengths of their roles. The reshaping is to learn what was not safe. Children need an environment in which they can learn skills their natural survival techniques are not allowing them to learn. We want children to learn balance. The goal is not to take a responsible child and make him irresponsible or an adjusting child and make her inflexible or a placating child and make him totally egocentric. Nor do we want the mascot to lose his or her sense of humor. We want children to experience choice about how they respond to different situations.

The reshaping of roles generally means changing our expectations of children’s behaviors and changing our behavior toward them. Instead of becoming immediately frustrated when the eight-year-old acts eight and insisting she behave like a little adult, allow her to display some of that normal eight-year-old behavior. This will require patience. When the placating child reaches out to placate one more time, rather than applaud, let him or her know you appreciate their thoughtfulness but you want to be alone and you are going to call an adult friend to talk. When the adjuster responds to open-ended questions with “I don’t know,” pause and reframe the questions where he has options to choose from. When the mascot uses her humor to distract, stay focused with what you expect from her in the moment.

Adults need to take responsibility where they can. Spreading the responsibility may mean providing a babysitter, even though the ten-year-old is extremely responsible and nearly as capable as the fifteen-year-old babysitter. It could mean that the parent gets up twenty minutes earlier in the morning and prepares a casserole. This makes the adult responsible for dinner and not the twelve-year-old. Children need your support and encouragement to make friends and to be involved in afterschool play activities. Applaud and encourage them to take time out to play and laugh.

Do not deemphasize the importance of responsibility with overly responsible children. Instead, emphasize parts of their characters they have not yet actualized—their spontaneity, playfulness, and ability to lean on someone and to recognize that they are not compelled to have all the answers. It is okay to make mistakes. Responsible children need to be praised and have their deeds acknowledged not only when they are doing their best and acting as strong leaders, but also when other endeavors take them out of the leadership role, such as playing on a team without being the captain. Remember, while these children demonstrate leadership qualities, this personality characteristic will be healthy only when it is not adopted as a matter of survival. Reinforce the children’s natural need to share with and lean on others when they have to make decisions and work on projects. Let them know although they are bright and accomplished youngsters, they are still just that—youngsters.

Encourage children who are not overly responsible to take healthy risks and make decisions for themselves. They need to learn to trust their own decision-making processes. They need to find when they do make a decision that you will follow through and support them. Start with situations that are the least threatening and have the fewest possible negative consequences—what television show to watch, what to have for dinner, how to handle a project. These children must learn to feel good about themselves because of their own accomplishments and their own decisions, not because they seek approval. Remember, the placating child will gladly make a decision if that is what is necessary to obtain approval. The goal, however, is not to attain approval, it is to instill in children the ability to make their own healthy decisions, to learn organizational skills, and to know how to problem-solve. The mascot often takes risks but those risks are for the sake of attention, the risks that aid them would be in the area of taking responsibility for themselves.

It is normal that children will feel awkward about making changes. Change in any system, even when that change is positive, is often met with resistance. As you assist in reshaping roles, children may exhibit confusion, withdrawal, or anger. When the ten-year-old has been busy playing the mother and the little adult when you suggest she try to play hopscotch and giggle with her friends—behavior that has been totally out of her realm of reality—it’s very likely she will initially push back or rebel in some way.

A similar rebellion will come from the adjusting child when you ask him to share his anger or hurt. For the son who managed to stare at the television while his father was ranting and raving and showed no signs of being affected, to share feelings now seems far beyond his present capabilities. The mascot is most likely to look at you as if you are speaking a foreign language.

To ask the placating child who has been taking care of everyone else’s feelings to focus on herself rather than others is equally foreign. Being self-focused does not give her the satisfaction she felt in taking care of others. She has learned to feel good about herself only when she is helping others.

Reshaping roles needs to be done slowly and is more effective when several adults are involved in the process. Encourage extended family members, school personnel, family friends, and those who are in a child’s life how they can be helpful.

Recommended reinforcing behaviors for responsible children:

• Give attention at times when the child is not achieving.

• Validate the child’s intrinsic worth, and try to separate feelings of self-worth from achievements.

• Let the child know it’s okay to make a mistake.

• Encourage the child to play.

• Emphasize parts of the child’s character not yet actualized, i.e., playfulness, spontaneity, ability to rely on someone else.

Recommended reinforcing behaviors for adjusting children:

• Engage in one-to-one contact to learn more about the individual child.

• Point out and encourage the child’s strengths, talents, and creativity.

• Bring them into decision-making process, giving them win-win choices.

• Engage in their personal interests.

Recommended reinforcing behaviors for placating children:

• Assist the child in focusing on him- or herself instead of others.

• Help this child play.

• When the child is assisting another, ask how he or she is feeling.

• Validate the child’s intrinsic worth, separating his or her worth from his or her caretaking.

• Reinforce there are others who will take care of other people, that is not the child’s job.

Recommended reinforcing behaviors for mascot:

• Give the child responsibilities with importance.

• Encourage responsible behavior.

• Hold the child accountable.

• Insist on eye contact.

• Encourage appropriate expression of humor.

For the acting-out child, recognize that this child is exhibiting unacceptable behavior because of family problems and the inability to get his or her needs met. Sometimes acting-out children were initially responsible and sensitive to others but found it brought them no satisfaction. The consequence of their dissatisfaction is rebellion—rebellion used to ward off pain. Many acting-out children have the ability to lead and can respond sensitively to others when in the right environment. These children must learn new productive outlets for anger; these children need validation and consistency in their lives.

Recommended reinforcing behaviors for acting-out children:

• Let the child know when behavior is inappropriate.

• Give the child compliments and encouragement whenever he or she takes responsibility for something.

• Develop empathy for the child by looking at what may lie underneath his or her attitude and behaviors.

• Set limits. Give clear explanations of the child’s responsibilities and clear choices and consequences.

• Give the child opportunities for healthy leadership.

When reshaping roles be cautious though for children still in active addictive family. It may be unrealistic for them to let go of certain parts of their rigid roles within the home. A ten-year-old may be the adult within the home, but if we can help that ten-year-old be ten outside of the home, we are helping that child to develop more fully. For example, it may be more helpful for this child to do the laundry at home in order to have clean clothes for school, rather than to encourage her not to if it means no clean clothes. The flexibility of the adjuster may be exactly what is needed if she is still subject to personality changes of one or both parents. That said, you can still build in greater resiliency by offering the child additional coping skills.

People of all ages need help, advice, and guidance; these messages are best transmitted when both words and actions coincide.

Expectations in Parental Recovery

Katherine was twelve years old when her father was first getting sober. She had very little denial about her father’s addiction and was thrilled her father had gone to a treatment program. Shortly after her father returned home, Katherine reported to her support group, “Everything is just really wonderful.” She is smiling and has absolutely no problem in the world. Katherine believed because her father was now clean and sober he was going to wake up and no longer being anesthetized, which meant Dad was going to discover his twelve-year-old daughter. But Katherine’s father had been an addict all of her life and that meant he was going to discover how little he knew his young daughter. Katherine’s life just couldn’t remain all roses. In a matter of weeks, her mother said that she was having a difficult time in school. One day, I challenged her, “Katherine, things aren’t fine, are they?”

“Oh yeah, they are just fine,” she responded.

I said, “No, things are not just fine. Things are often not good even though a parent gets sober.”

In the form of an art exercise, she drew a picture of her dad looking happy, but she looked sad. Underneath the picture of their faces, she wrote, “I have a hard time understanding why my dad goes to those meetings every night, and why he is not home.”

Katherine had a lot of expectations, many of which were fantasies, about how she and her father were going to spend so much time together now that her dad was sober. The fact was, in his initial recovery, her dad was so actively involved in twelve-step meetings that he spent nearly as little time home as when he was using. Katherine did not understand; she was confused and very angry, and she immediately reverted to her denial system in order to protect herself from the feelings she was experiencing. Her father did need all those meetings. It is not sufficient for a counselor to explain this need to children and partners. Katherine needed her father to share his feelings about the meetings and to share his thoughts about recovery. If parents need time away from families to attend meetings, it is important for them to explain and share with the family how vital and necessary this part of their recovery program is for them. Nonetheless, Katherine’s father still needs to find ways to connect to his daughter. With healthy communication and even a small amount of concentrated father-daughter time around something that Katherine was interested in, be it her bird collection, her art, or a video game, Katherine could have the patience needed to not build up resentments.

Sydney encountered a similar situation with her children. She found that by telling her kids what she learned at each meeting, making a point to always eat dinner with them and to always say good night, and by designating special time every two weeks with each of her children, she didn’t need to reduce the number of meetings she attended nor feel guilty about her parenting.

People struggle with parenting when they have not had healthy parental modeling, when their emotional growth has been stunted due to their addiction and or codependency. While recovery doesn’t suddenly give someone parenting skills, it does give them a foundation for honesty and accountability. Due to guilt there is this pull to give a child whatever they want or to simply stay away from parenting. Essential though is remembering a parent’s job is to be a child’s best parent not their best friend. There are many resources to guide parents, but it all begins with commitment to your own recovery.

We cannot always change the environment children are raised in, but we can change what they believe about themselves.

We need to help children overcome the need to medicate or run from their feelings. We need to assist them in developing problem-solving skills. We need to help them know they are of value and they are worthy. It sounds like a lot, but if we are willing to offer education about addiction, validate children in their feelings, assist them with problem-solving, respond to protection issues, and facilitate a greater support system, we will genuinely create more resilient children who have far greater choice about how they will live their lives.