On Lyndon Johnson, Rutherford B. Hayes,

Franklin Roosevelt, Harry Truman, Richard Nixon,

and Chester Arthur, and America’s Presidential Libraries

IT MAKES sense that someone humble and reserved like Calvin Coolidge would have a relatively small headstone and burial plot. But a gregarious Texan like Lyndon B. Johnson, who has space centers and freeways named in his honor? You’d expect something big and prominent. Yet his grave is unexpectedly small: he’s in a walled family cemetery up the road from the LBJ Ranch in Stonewall, a town just west of the Pedernales River in the heart of the Texas Hill Country. The headstone is one in a row of red granite markers, only slightly larger than the others. Mrs. Johnson’s marker is the same size and shape; at a distance, the American flag in front of LBJ’s stone is the only way to tell them apart.

Johnson wasn’t looking for prominence in the afterlife—just quiet. “I come down here almost every evening when I’m at home,” he said of the cemetery. “It’s always quiet and peaceful here under the shade of these beautiful oak trees.”

Now, what Johnson did on the rest of the LBJ Ranch—2,700 acres during his presidency, complete with its own airstrip—was anything but quiet. “This is my ranch and I do as I damn please,” he liked to say at home, so often that the family embroidered the line on a pillow for him. In the dining room, the president, over his wife’s objections, liked to roll his chair a few feet to the right during dinner to monitor the news on a set of three TVs in the living room (one for each network at the time). If a news story got his dander up, Johnson would roll back to the left and grab the phone, specially installed under the table, to chew the reporter out.

All this noise helped Johnson in other ways, too: often at dinner he would distract guests so that he could switch out the low-fat dessert his doctors wanted him to have with one of their regular desserts.

After taking in Johnson’s ranch, I drove back east to Austin to see the LBJ Library, next to the University of Texas. Johnson’s library was the first to open with a university affiliation, but it’s not all scholarly gravitas when you head inside. In fact, the man at the front desk gave me four words of advice as I set out on my library tour: “Start with the robot.”

14. The Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library and Museum has a life-size, joke-telling animatronic version of its namesake.

The Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library and Museum has a life-size robotic version of its namesake—and it’s a joke-telling robot, no less. Mechanical LBJ stands behind a podium, and in front of a wide array of editorial cartoons and caricatures, and cracks jokes, which run on a loop. Johnson’s jokes were woven into stories, unlike the one-liners for which John F. Kennedy was known—but they’re worth the wait. I heard the robot tell a tale about a man who refused his doctor’s orders to quit drinking or he’d lose his hearing. According to the robot, the man told the doc, “I just decided that I liked what I drank so much better than what I heard.”

The robot gestured as it spun its tale, and I think that because I grew up in the era of the Rock-afire Explosion, the animatronic animal rock group that performed at Showbiz Pizza, I imagined that the gears made noise as he moved, so he sounded more like this: “I just decided—WRRRRRRRRRRRRDDDDDDDD—that I liked what I drank—ZZZZZZZEEEEEZZZZZZZZ—so much better than what I heard.—PSSSSSSOOOOOOOFFFFF.”

Nobody here intended a joke-telling animatron to be the big draw at the library of one of the most consequential presidencies of the twentieth century. “It was meant to be an addendum,” library director Mark Updegrove told me. In fact, he says, “when we had our renovation we contemplated getting rid of the robot. But the public outcry was such that the robot had almost become like Big Tex out here in Texas, almost as iconic.* And so we kept it.” The library not only kept Robot LBJ but gave him an upgrade, including a suit and tie to replace the ranch clothes he’d worn since he started his illustrious career as part of a Neiman Marcus display on Texas history in 1997. Austinites, who take their weirdness seriously, worried whether a suit-and-tie robot would meet their needs, but that robot could keep the city weird all by itself. Even Updegrove has a soft spot for the bot: “My epitaph may well say ‘the man who saved the LBJ animatron,’” he said at the time of the upgrade. “And I am just fine with that.”

The LBJ robot isn’t one of a kind; Walt Disney World’s Hall of Presidents has had talking animatronic presidents since its opening in 1971. It isn’t even the only robot on a purely presidential site: I met a William McKinley robot at the McKinley museum in Canton, Ohio. Robot McKinley brushed off his robotic wife’s concerns about his plans to greet the public at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo. “There is nothing to fear from the American citizens who disagree with me politically,” he says. Robots do dramatic irony really well.

But Robot LBJ is the best of the lot, and the hypercompetitive Johnson would undoubtedly approve of that. Presidents tend to be competitive people, and the presidential libraries are where they compete against each other. Speaking at the Johnson Library in 2013, George W. Bush noted that “former presidents compare their libraries the way other men may compare their—well . . .”

Johnson’s library takes this metaphor almost literally. The architect, Gordon Bunshaft, described the building this way: “The President was really a virile man, and he ought to have a vigorous, male building. And we have got a vigorous, male building.” It’s ten stories in all, eighty-five feet high, and about 120,000 square feet. Even the documents here are dramatic: one side of the central room, the enormous Great Hall of Achievement, is a series of glass windows showing off four stories of documents, more than forty thousand bright red storage boxes embossed with gold presidential seals. They’re positioned above a massive row of murals showing Johnson with Presidents Roosevelt, Truman, Eisenhower, and Kennedy. Mark Updegrove sums up the building perfectly: “It looks like power.”

Johnson didn’t just want the biggest building, he wanted the most people, too: he spent inordinate amounts of his time in retirement hounding library staff for the latest admission numbers, or tracking the number of postcards people had bought in the gift shop. Sometimes he ducked out to the parking lot to look at license plates and see who was visiting. And he was forever trying to think of ways to drum up more visitors. Once he suggested the library open at 7 a.m. and hand out free doughnuts; another time, he had the University of Texas football announcers remind stadium-goers that there were public bathrooms close by at the library.

15. Lyndon B. Johnson looks closely at an architectural model of his library; he would keep an even closer eye on the library’s admissions numbers and postcard sales.

LBJ was happy to use his famous powers of personal persuasion to boost foot traffic, too. At a book signing in 1971, Johnson decided the crowd should be bigger—so he went outside to round up passersby. The library staff, dutifully clicking a counter each time a visitor came inside, added these new people to their tally, and counted the large group that followed Johnson outside a second time as they shuffled back in. (Some staffers later admitted that, given the boss’s preoccupation with attendance, the final numbers were maybe, just maybe, a little tiny bit inflated.)

Johnson’s funeral services included a stop at the library. Director Harry Middleton made sure that every last one of the thirty-two thousand people who came to see the president’s casket in the Great Hall were counted, because, he said, “I know that somewhere, sometime, President Johnson is going to ask me.”

Benjamin Hufbauer, a presidential library scholar who teaches at the University of Louisville, says the development of the presidential library is the big turning point in how we memorialize presidents. Previously, he says, “there was a sorting process. History kind of judged—Millard Fillmore doesn’t get an obelisk in the middle of Washington.” It was up to posterity to decide whether a president was worthy of his own statue on the Mall. Now, Hufbauer says, “they don’t wait for posterity to do it. They start memorializing themselves.”

Presidential libraries began with one of the most mild-mannered presidents, Rutherford B. Hayes. To be fair, “Rud” was described in his Civil War days as “intense and ferocious”—he was wounded five times on the battlefield, in fact—but as chief executive the reserved, bearded Buckeye president didn’t set the world on fire with charisma. It was the same story at home in Fremont, Ohio, where Hayes’s favorite pastime was inviting a prominent political figure to stroll the front lawn and place his hands around the trunk of a tree, which Hayes would then name for him.

This wasn’t the kind of guy for whom you’d build a joke-telling robot. Nevertheless, without the Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Center there wouldn’t be a robot at the LBJ Library in Texas—or a library at all.

Before Hayes, presidents kept their papers private. George Washington, as usual, established this custom, by lugging his presidential papers back with him to Mount Vernon. Unfortunately, some presidents didn’t do as well as others in keeping those papers intact. Rats and moist conditions “extensively mutilated” some of the irreplaceable papers from the first administration. Fire proved to be a hazard for presidential papers as well; many of Andrew Jackson’s and William Henry Harrison’s papers burned. Union soldiers accidentally destroyed most of Zachary Taylor’s papers as they ransacked the Louisiana home of Confederate Major General Richard Taylor, his son. Of the papers that did survive, many stayed off-limits to researchers.

Other presidents sold or donated their papers to the government, or willed them to family members, and these papers were better protected. John Quincy Adams’s will charged his son Charles Francis with building a fireproof structure to contain both his and his father’s presidential papers. After James A. Garfield’s assassination in 1881, his wife, Lucretia, built a sort of memorial addition onto the family home in Mentor, Ohio, with a massive portrait of General Garfield in the stairwell, a spacious wood-paneled reading room to hold Garfield’s thousands of books, and a stone vault for his papers, the floral wreath Queen Victoria sent for the funeral, and some of the president’s walking sticks.

But these papers stayed out of public view for decades. The Adams descendants eventually donated their papers to the state of Massachusetts, but on the condition that they be kept private for another fifty years, well into the twentieth century. Garfield’s family didn’t want Americans beating down their door for a look at his papers. Even Lincoln’s family required that the Great Emancipator’s papers be kept under lock and key until the 1940s.

Established in 1916, the Hayes Presidential Center was the first facility intended to protect a president’s papers and artifacts and offer them for public viewing. If you find that innovation riveting, you may be Paraguayan, as Rutherford B. Hayes is a bigger name in that country than in his own, and with good reason. Paraguay was in ruins in the 1870s: its leaders had provoked a war with three of its neighbors, who responded by signing a secret treaty to divvy up most of the country for themselves. The Triple Alliance—Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay—not only had better weapons and modern ships, they had a twenty-five-to-one advantage in troops. The battles were bloody; soon Paraguay was losing soldiers, weapons, and even clothes, and resorted to sending children into battle wearing carpets and carrying sticks painted to look like rifles. Two out of every three Paraguayans died by the end of the war; pretty much everyone else was starving.

Hayes came into the story several years after the war, when what was left of Paraguay was at odds with Argentina over a southwestern area known as the Chaco. The two countries turned to the United States for arbitration, and on November 12, 1878, President Hayes decided in favor of Paraguay’s land claims, which amounted to about 60 percent of the country’s territory today. Paraguay, having finally won something, decided to name about a fifth of the country after its American benefactor; the capital of the Presidente Hayes Department (in Paraguay, departments are like states or provinces) is Villa Hayes, there’s a soccer team in the area named Club Presidente Hayes, and there’s a bust of the former president outside the elementary school, although some of the kids apparently know Hayes simply as “the man without arms.”

It was Hayes’s second son, Webb Cook Hayes, who made the Hayes Presidential Center happen. Webb served capably as his father’s White House secretary, and later made a fortune cofounding Union Carbide, but got restless in his forties and ended up being one of the most daring military men of his age. Webb requested and received the most dangerous assignments he could find: he was wounded twice in the war with Spain, first in an assault on Cuba’s San Juan Hill—the same hill Theodore Roosevelt’s Rough Riders made famous—and again in an invasion of Puerto Rico shortly thereafter. Later, in China, he helped rescue future president and first lady Herbert and Lou Hoover, who had gotten caught up in the Boxer Rebellion. And Webb once snuck behind the lines of insurgents in the Philippines to aid a US military garrison cut off from the rest of the force; this feat won him the Medal of Honor.

Colonel Hayes, as he was known, offered the family’s sprawling thirty-one-room mansion, Spiegel Grove, and the surrounding twenty-five acres to Ohio’s State Archaeological and Historical Society, on the condition that they build “a suitable fireproof building . . . for the purpose of preserving and forever keeping in Spiegel Grove all papers, books, and manuscripts left by the said Rutherford B. Hayes.” He also required that “said building shall forever remain open to the public.” Ohio took the deal and spent $50,000 to fix the roads around the property and construct a 52,000-square-foot sandstone building. Webb Hayes pitched in $100,000 of his own for upgrades and endowments, and offered the library his extensive collection of American weaponry, some dating back to the Revolutionary War. He convinced Congress to give up the old gates to the White House for use at the Hayes Center—it took six years, but he got it done. And he had his parents, buried in nearby Oakwood Cemetery, reinterred in a shady corner of Spiegel Grove, under a tall granite monument Rutherford B. Hayes had dreamed up himself. Walk to the rear of the grave and you’ll find markers for Webb Hayes and his wife.

Hayes’s 1893 funeral drew figures from all over the country, including Grover Cleveland, the former president who was several months away from returning to the office. Cleveland was riding in a funeral carriage at Spiegel Grove when, as one observer noted, “the crowd of men in uniform caused the horses to plunge forward and for a moment it was feared that President Cleveland would be thrown to the ground.” Cleveland “recovered himself promptly by the aid of a mammoth shell-bark hickory against which he leaned and since that time the tree has been known as the Grover Cleveland Hickory.” One last tree for the road.

The funny thing is, had one guy voted differently in 1876, Hayes might not have been in the White House to become a Paraguayan hero or have a presidential library. His opponent, New York governor Samuel Tilden, won the most popular votes, but the 1876 election was, as one observer put it, the “Ugliest, Most Contentious Presidential Election Ever.” The election included vote fraud of every kind, illicit backroom deal-making, and election boards offering to certify the winner for a price. The dispute got so contentious there were concerns, though probably overblown, that the country would sink back into civil war over the outcome.

Hayes backers fought to claim every last electoral vote; Tilden, inexplicably, spent several weeks writing up a report on the history of electoral college procedures, which he thought would convince a special electoral commission to decide the election in his favor. They didn’t, of course, and Hayes ended up in the White House. Tilden, to his credit, kept his head up after the win/loss. “I shall receive from posterity,” he said later, “the credit of having been elected to the highest position in the gift of the people, without any of the cares and responsibilities of the office.” Then again, Tilden’s massive tomb in New Lebanon, New York, very pointedly refers to his status as the man who came as close as a man can to winning the White House without actually getting there: “I still trust the people.”

FRANKLIN DELANO Roosevelt was thinking of Hayes and his museum when he started dreaming up his own library, which is the model each president has used since. “FDR was a great fan of saving things,” explains library director Lynn Bassanese, who retired in 2015. “He had so much stuff—he had so many ship models, he had so many maps, he had so many books.” Roosevelt’s stamp collection was one of the most celebrated in the world, and he proudly hung on to what he called “oddities”; his taxidermy collection, for example, included some three hundred species of birds.

The president’s biggest and most important collection, of course, was the millions of papers, letters, and documents from his long career in public service. “He wanted a place,” Bassanese says, “where historians could look through his documents and write the story of his presidency.” He didn’t want the collection to be housed in the Library of Congress, though, or even the National Archives, which he’d signed into law in 1934. Roosevelt said he was worried about what might happen if the country housed all of its crucial documents together and an enemy attacked; Spain’s civil war had, in fact, led to the destruction of some of the documents in that country’s central archives. But Benjamin Hufbauer, the presidential library scholar, says what Roosevelt really wanted was a place to tell his story. “Roosevelt,” he says, “comes up with this library and says, it’s my home, it’s my land, I’ll be buried there, it will bring everybody full circle. This will be a shrine to my life.”

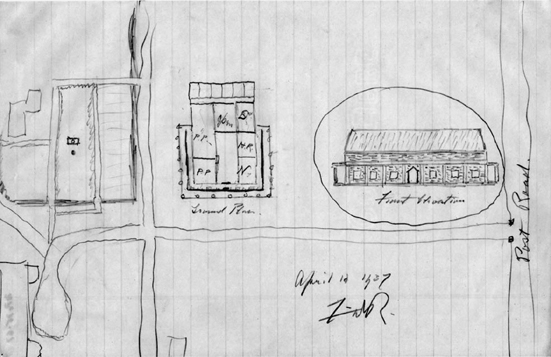

So, on April 12, 1937, FDR sketched out the “shrine”: a stone Dutch colonial structure on the grounds of his family home in Hyde Park, New York, to house his official papers and display his personal artifacts for the public. Remember, Roosevelt was still president in 1937. “Only an egocentric megalomaniac would have the nerve to ask for such a measure,” groused one Missouri representative. Hamilton Fish, who represented Hyde Park in Congress, called the proposal “utterly un-American, utterly undemocratic. It goes back to the days of the Pharoahs, who built their own images and their own obelisks. It goes back to the days of the Caesars, who put up monuments of themselves and crowned them with laurel leaves, and posed as gods.” Nevertheless, after some stalling, pro-Roosevelt majorities in Congress approved the library bill in 1939, construction began shortly thereafter, and the structure was open in 1941.

16. On April 12, 1937, Franklin Roosevelt sketched out what would become the first government-run presidential library: a stone Dutch colonial structure to house his official papers and display his personal artifacts for the public.

Roosevelt had intended to help historians sort through his papers after he retired to Hyde Park. His death in office in 1945 put an end to that, but his library was the final stop on one of the most unusual funeral journeys in American history: the mourners on Roosevelt’s eighteen-car funeral train from Washington to Hyde Park included the new president, Harry Truman, the cabinet, the entire Supreme Court, and top leaders from Congress and the military. The most essential personnel in the US government took the same funeral train—one, mind you, that had its entire schedule printed in the newspapers—while World War II was going on. It was astonishingly risky, but fortunately the train arrived without incident, and Roosevelt was laid to rest in the family’s rose garden—appropriate, given that “Roosevelt” means “field of roses” in Dutch. Eleanor Roosevelt joined her husband after her death in 1962; their burial plots are next to a white oblong stone inscribed only with their names and life-spans, with bright red, yellow, and purple flowers at the stone’s base.

17. When Franklin Roosevelt played coy about whether he’d seek a third term, reporters characterized him as Sphinx-like—and one made it literal, in this papier–mâché bust.

“And of course it’s not just the grave for the president and the first lady,” Lynn Bassanese says, “but underneath the sundial are two of the dogs. There’s Fala, and then there’s a German shepherd who had belonged to his daughter, named Chief.”

The inside of the library has unusual treasures as well. My son galloped from room to room while I perused a wall-sized chart about New Deal government spending. Soon he galloped back to me. “Papa, come here,” he said. “I saw a big head.” It was Roosevelt’s head—made of papier-mâché and shaped like the Sphinx. Bassanese told me the whole story: “It was at the Gridiron Dinner in ’39, and FDR had not been very open about whether or not he would run for a third term. It was like he knew all but wouldn’t speak, so there had been a lot of editorial cartoons depicting him as a Sphinx. A reporter created this in his basement, and a lot of people might have taken offense to that, but he had a great sense of humor, and when he saw it he laughed and said, when this is all done I want this for my library.”

FDR’s library might have been one of a kind, had it not been for his successors’ decisions to build libraries of their own. “If one or two between then had said ‘no, I don’t want this,’” Lynn Bassanese said, “then we might have had a very different library system.” Each of the following presidents (plus Herbert Hoover, whose library opened in 1962) built upon the Roosevelt model and added his own touches. Harry Truman worked out of an office in his library; he loved to come out and give visitors personal tours, and asked to be buried in the library courtyard, “so I can get up and walk into my office if I want to.” Dwight Eisenhower built his library on a tract of land around his boyhood home in Abilene, Kansas.

Every presidential library has its odd side, like the giant Sphinx head in Hyde Park. Gerald Ford’s museum, in Grand Rapids, Michigan, chronicles his years in politics and hosts his elegant tomb, a semicircular stone built into the side of a hill overlooking the Grand River. But the library also tells the story of the 1970s, complete with a pair of disco mannequins in mid-hustle, as Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On” plays from the speakers overhead. The Richard Nixon Library in California has a life-size cutout of the president’s famous photo with Elvis Presley, as well as the pistol the King brought to the White House as a gift. Bill Clinton’s library in Little Rock, Arkansas, has on file ashes from the president’s cat, Socks. And, of course, there’s Robot LBJ in Austin.

Roosevelt described his library and its contents as “a mine for which future historians will curse as well as praise me.” The main criticism of presidential libraries is that there’s usually too much praise and not enough cursing. The presidents raise private funds to construct the facilities, which they turn over to the National Archives and Records Administration. Each is part document storehouse and part public museum, using artifacts and official papers to tell the story of the president and his times.

One of Benjamin Hufbauer’s favorite phrases to describe the libraries is “archives of spin”; the other is “propaganda museums.” “The exhibits in newer presidential libraries often amount to little more than extended campaign commercials in museum form,” he says, “because the former president and his supporters essentially control the content.” The FDR Library, for example, didn’t put in a display about Japanese American internment until the mid-1990s, decades after it took place and nearly a decade after the US government formally apologized for the internment camps. Originally Ronald Reagan’s library showed plenty of movie memorabilia and little about the Iran-Contra scandal, and the LBJ Library avoided discussion of Vietnam at first. Its founding director, Harry Middleton, described the dynamic at work in a first-generation library: “We really wanted to do a good job, but we also surely wanted to make sure it was OK with [President Johnson].”

But the libraries have a life cycle: as the president and his contemporaries leave the scene, scholars move in and fill in some of the gaps in a museum’s narrative. Lynn Bassanese says this was one of the big goals of the 2013 renovation at the Roosevelt Library: “We wrote the exhibit script with a committee of historians and asked, what’s the story here? What are the essentials here? And we crafted the exhibit script that way. Then we took it a step further and created ten computer stations called ‘Confront the Issues,’ and they’re touchscreen stations. And what they do is include excerpts from historians about some of the more controversial issues, like Japanese-American internment, the Holocaust, his health—whether or not he was healthy enough to run for the fourth term.

“What we can do,” she continues, “is show lots of the documents the president saw, what his advisers said he should do, and then in hindsight, show what historians have said about those decisions. And that gets us away from those complaints that the libraries are telling just one side of the story.” The new FDR Library doesn’t stop at the issues—it has no less than three panels about the president’s extramarital relationships, as well as a note about Eleanor Roosevelt’s “closeness to pioneering newspaperwoman, Lorena Hickok.”

The earliest of the presidential libraries have come the longest way in giving both praise and criticism for their subjects. Harry Truman’s hometown of Independence, Missouri, lauds its most famous citizen plenty; the downtown historic district lets visitors tour the Truman family home, get an ice cream soda at the shop where young Harry worked, or stop by the men’s shop called Wild About Harry. But the president gets no free ride at the Truman Library: the exhibits sometimes disagree with him. One of the walls includes a list of Truman’s legislative failures next to his accomplishments; another says pointedly that the Truman Doctrine may have “helped guide the nation into a conflict in Vietnam that did not involve America’s national security.” The exhibit on the atomic bomb includes plenty of prominent voices who say Truman’s decision to use atomic weapons in World War II was the wrong one.

In his book on presidential libraries, Benjamin Hufbauer pointed toward the Truman Library to show how these museums can balance out over time. He’s not so sure now, though. “I think my position has changed,” he says. “I think the idea that historians are going to push it and modify it and make it more balanced isn’t the case. Truman was, as presidents go, relatively modest. The way that it used to work was that the presidential foundation would be established, [the foundation] would raise money for the library, and when it was finished, it would turn the library over to the government and exhaust itself and stop fund-raising.

“That model no longer exists. With Carter, Clinton, Reagan, the two Bushes, the foundations are still active. The children and grandchildren are still involved, and they’re not going to let historians—they’re not going to let go of control, long after the president is dead.” Hufbauer says these families-vs.-historians struggles will play out much like the struggle over the Watergate exhibit at the Richard Nixon Library in California. Originally this was a private facility run by the Nixon Foundation, so its exhibit on the scandal, “The Last Campaign,” made the president sound more like a victim of the scandal than one of the perpetrators. That changed in 2007, when the library formally affiliated with the National Archives and Records Administration. Its new, NARA-appointed director, Timothy Naftali, almost immediately moved to dismantle “The Last Campaign” and spent years developing a new take on Watergate.

The new exhibit, unveiled in 2011, starts with a Nixon quote—“This is a conspiracy”—and continues in that unflinching tone through the long national nightmare of break-ins and cover-ups and Supreme Court cases and resignation. There are some forty hours of video in which those involved in the scandal and the investigation share their memories, and there’s a look at the legislation that came out of Watergate, from changes to campaign finance and open records laws to the Presidential Records Act, which formally put all presidential papers into the library system.

(My favorite part of the Watergate exhibit is called “Listen to the Gap,” where you can listen to the portions of a White House recording from June 1972 that someone erased, destroying potentially important evidence in the Watergate investigation. Since it’s been erased, all you hear is the erasure clicks and occasional buzzing.)

The revamped display won mostly accolades from the public, but foundation backers fumed. Bob Bostock, a former Nixon staffer who had written most of the original exhibit, complained that the Nixon Library had now launched “an unapologetic attack” on its namesake. “It is as much a polemic as the original exhibit was,” he wrote in the foundation’s lengthy and very public response to the exhibit. “The difference is that the original exhibit never claimed to be impartial.” Archivists and volunteer docents quit in protest; for a while, some foundation staff and library staff didn’t speak, even though they worked in different parts of the same building. Naftali joked with one reporter that he worked out to cope with stress, and that working at the Nixon Library had gotten him into peak physical condition. He ended up quitting himself, barely six months after the opening of his Watergate exhibit.

The relationship between private foundation and public entity clearly can get complicated. So why not just leave the libraries entirely private, as the Nixon Library used to be? “So they can have the government pay for it,” Hufbauer says. “We’re talking maybe three to four million dollars a year for staff, keeping the lights on, and so forth. But also because [NARA affiliation] gives it official sanction. If you were to just run it by yourself and say ‘We’re going to run this propaganda museum,’ you wouldn’t have that official sanction.” Conversely, no library is moving to cut out the private foundation, either, not when they’re the biggest financial backers and cheerleaders the libraries have.

Hufbauer says the “sheer weight of the documents” is the biggest problem facing the system today. “Eighty, ninety million documents, and increasingly in digital forms—it’s a labor-intensive process to go through those,” he says. “It takes eyes and hands and minds of trained archivists to look at these. And they’ve simply not kept up with the hiring of archivists with the level of documents.” At the current rate, the Bill Clinton and George W. Bush libraries aren’t expected to finish sorting through their documents for decades, or maybe even a century—and an executive order Bush signed in 2001 allows presidents to block the release of virtually any documents for virtually any reason, including plain old politics. Meanwhile, the museums, which the presidents and their backers shape, get bigger and fancier and more enticing for visitors. Presidential libraries are growing larger and smaller at the same time.

They’re also more in demand than ever—at least by the potential host sites. A huge presidential library can serve as an economic anchor for a city or a neighborhood; the construction of Bill Clinton’s library in Little Rock spurred a billion dollars of private investment in the surrounding area. And most libraries affiliate with nearby colleges or universities. “It is a prestige builder,” says Skip Rutherford, dean of the Clinton School of Public Service at the University of Arkansas. “It is a recruiter. People look to the program, even if it’s not directly on the campus.” No president has been short on bidders for a library site.

Only one president has been short on enthusiasm for placing his name in history. Chester A. Arthur never wanted the top job; he was content to be a nondescript machine politician in New York. But in 1880 the Republicans nominated Arthur as James A. Garfield’s running mate to smooth out a squabble between two party factions. In less than a year, Garfield was a martyr and Arthur was the muttonchopped, well-dressed “Dude President.” His first act in office was to lock himself in the bedroom and cry.

To Arthur’s credit he rose to the occasion, winning over a skeptical public, and enraging the political bosses, by refusing to do any more dirty work for the machine. Former friends wondered what happened to their man Chet Arthur. “He isn’t ‘Chet’ Arthur anymore,” one concluded. “He’s the president.”

Perhaps the president’s former friends didn’t know about the nonflunky side of his personality. Arthur served with distinction in the Civil War, efficiently overseeing housing and provisions for hundreds of thousands of New York soldiers. As a young lawyer in Manhattan, he had successfully defended an African American woman called Elizabeth Jennings, who faced a charge of refusing to get off a streetcar to make room for white riders. This was in 1854, a century before Rosa Parks. Even so, Arthur played his cards pretty close to the vest, telling one White House guest, “I may be President of the United States, but my private life is nobody’s damned business.”

And he meant it. The president’s grandson, Chester A. Arthur III, told the Library of Congress that “the day before he died, my grandfather caused to be burned three large garbage cans, each at least four feet high, full of papers which I am sure would have thrown much light on history.” Because of that, Chester Arthur is one of the least well known presidents. There is no Chester Arthur Foundation raising money for exhibits at a Chester Arthur Presidential Center, and there are few historic sites retracing Arthur’s life or career. His tomb, just outside of Albany, is the most striking of all the president’s graves—there’s a weeping angel standing over his sarcophagus—but it doesn’t give up many answers. Arthur’s Manhattan home is equally impressive, but there’s no museum there, just a small plaque on the outside of the building at 123 Lexington Avenue; the twenty-first president’s lone National Historic Landmark is better known as Kalustyan’s international grocery, “a landmark for fine specialty foods.” There are only two Arthur statues, and the one in New York City shows the president holding up a pair of eyeglasses—which aren’t there, because somebody swiped them from his hand.

Chester Arthur got the obscurity he wanted, but without another like him in the White House, the presidential library is going to be with us for a while. Presidents just want them too much to let them go. “In America,” Benjamin Hufbauer says, “there is an obsession with the presidency. And presidents are the people most obsessed with it.”

* Big Tex was the giant talking mascot of the Texas State Fair. He caught fire at the end of the 2012 fair, around the time Robot LBJ’s fate was being decided.