GEORGE WASHINGTON’S tomb at Mount Vernon was the obvious starting point for this adventure, so I started there. But where to finish? Where does a person wrap up a tour of the gravesites of the presidents?

I thought about this as I walked the grounds of Dwight D. Eisenhower’s presidential library. Ike wasn’t going to be my last visit—there were still several names left on my list when I visited him in Abilene, Kansas—but his burial site was the first I sized up as a potential finish. In some ways it would have been a good fit: the Eisenhower site is twenty-two acres, a size befitting his historical stature. Staff members shuttle from building to building in small yellow pickup trucks with “We Still Like Ike” signs on the back. There’s a federally managed presidential library for his official papers, and a museum showing Eisenhower’s White House desk, the Emmy Award he won for his use of television in office, and some of the paintings he made in retirement.

Outdoors, the centerpiece of the campus is a large statue of the general and a series of plaques marking this as the site in which the president’s parents taught their six sons “the ways of righteousness, of charity to all men and reverence to God.” Eisenhower’s indoor burial site, the Place of Meditation, is styled after military chapels, with stained glass windows, wooden pews, and a bubbling fountain.

In other ways, though, Eisenhower’s story isn’t the one to bring me full circle. Instead of returning home on Air Force One, as presidents do today, Eisenhower came back to Kansas on a train—the last presidential funeral train. More importantly, Eisenhower’s posthumous story is still being written. In 1999 Congress authorized a commission to create a memorial in Washington to the thirty-fourth president. In 2005 the commission chose a four-acre site near the National Air and Space Museum; four years later it hired the prominent architect Frank Gehry to design the memorial. Though there was wide agreement on honoring Eisenhower, Gehry’s design was less popular: critics compared some of the design’s metal columns to missile silos and even Communist-style iconography, while others complained about a statue depicting Eisenhower as a “barefoot boy” in Kansas.* Eisenhower’s own children spoke out against the design, and Congress suspended funding for the project until the two sides could reach agreement. “This memorial cannot be built,” said House Oversight Committee chair Darrell Issa, “if it is inconsistent with the views of the people who knew our commander in chief as well as his family.” Gehry agreed to design changes, and the process picked back up in late 2014, but it will be some time before those in Washington can walk through an Eisenhower Memorial.

This is the issue for me in finding a grand finale: each president’s story will grow and change over time, and as long as there’s a presidency, there won’t be a “last” president whose story can serve as a bookend to Washington’s. Part of me wishes that all the presidents who are still with us will live to be five hundred, but I know inevitably we will get word someday that one of them has left us, and the military will carry out a detailed funeral plan and lay that president to rest, and I’ll make it a point to stop by.

Many of my last few presidential visits were technicalities, like my visit to see Grover Cleveland, the only president to serve two nonconsecutive terms, on a second, nonconsecutive occasion. Or Jefferson Davis: like him or not, the Confederate chief executive is part of the American story now, and besides, he’s in the same Virginia cemetery as James Monroe and John Tyler. And there’s the story of David Rice Atchison, whose grave marker in Plattsburgh, Missouri, reads “President of the United States for One Day—Sunday, Mar. 4, 1849.” Atchison was president pro tempore of the Senate in 1849, when new president Zachary Taylor and new vice president Millard Fillmore declined to hold their inauguration on a Sunday. This led to a theory that, under the laws of succession at the time, Atchison was technically president until Taylor took the oath on Monday. He wasn’t: legally, presidents don’t have to take the oath to start their terms, and Atchison’s own term as president pro tem had expired along with the executive’s term. Still, he liked to tell the story—especially in retirement, possibly to rebuild his public reputation (Atchison backed the South during the Civil War). Atchison’s administration was, by his own admission, hands off. “I slept most of that Sunday,” he said.

But no presidential quest could be complete without a visit to the most iconic site of all: the gigantic presidential heads of Mount Rushmore. The story here, at the so-called shrine of democracy, is enormously ironic: Mount Rushmore was designed not to be a touchstone of American identity but as a tourist trap. In the 1920s, South Dakota state historian Doane Robinson wanted to draw more visitors to the Black Hills, and as he put it, “tourists soon get fed up on scenery unless it has something of special interest connected with it.” It worked: the state gets some three million visits a year out of Rushmore, not to mention the economic benefits from the web of tourist-friendly businesses and attractions in the area. Whether Doane Robinson intended mystery spots, wax museums, and mini golf is probably up for debate, but, hey, he wanted tourists and he got them.

His original idea was a monument to heroes of the West, but his sculptor, Gutzon Borglum, shot the idea down for being too regional. He wanted to carve presidents, which he said would be more timeless, more national, and a lot more inspirational. “People from all over America will be drawn to come and look,” he said, “and go home better citizens.”

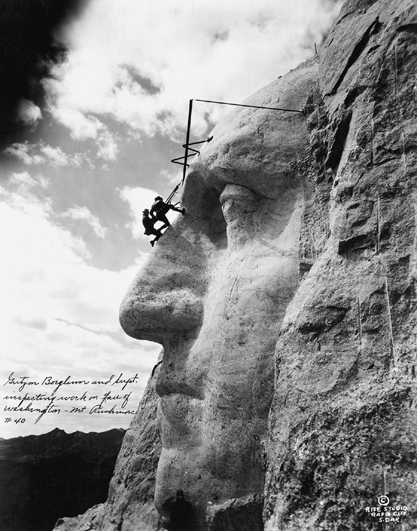

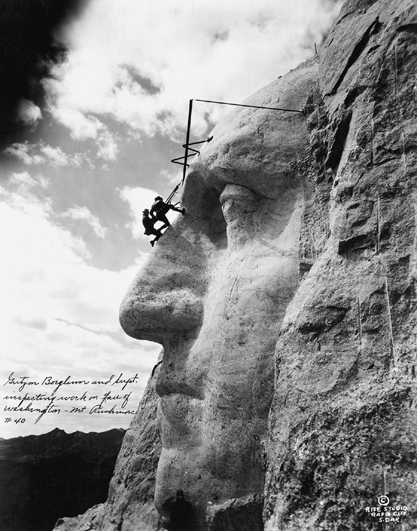

22. “The faces are in the mountain,” Gutzon Borglum said of Mount Rushmore. “All I have to do is bring them out.” Having brought them out, Borglum and a project superintendent inspect George Washington’s nose.

Borglum was a magnificent sculptor and not such a magnificent citizen; from 1927 to 1941, he carved the seemingly impossible into Rushmore’s granite facade but drove nearly everyone around him crazy during the construction process. He fought with everyone, including the “untutored miners” working long, dangerous shifts; Borglum’s son, Lincoln, was forever rehiring the men his father had canned, just to keep the work moving along. The lawmakers overseeing construction could barely stand him either. “No one could get along with Mr. Borglum for any length of time without losing his temper, unless one was a saint,” said former South Dakota governor and senator William J. Bulow, who dealt with the temperamental artist throughout construction. “I never had so many rows with any other person as I had with him.”

Borglum’s pre-Rushmore row was so big he had to flee the state of Georgia. In 1925 he was working to carve giant Confederate figures into Georgia’s Stone Mountain, but the project’s backers fired him for excessive spending and his “ungovernable temper.” Some of the people backing Borglum’s monument were affiliated with the Ku Klux Klan—and they said he was too angry. He proved them right by smashing the models, which technically belonged to the monument association, which called on the sheriff to arrest Borglum. The authorities chased the sculptor right up to the state line into North Carolina.

But despite his temper, Borglum the artist usually won over even those who were exasperated by Borglum the man. “The faces are in the mountain,” he said, over and over. “All I have to do is bring them out.” And people believed him: the workers kept trudging up 506 steps every day to set dynamite and chisel rock high on the peak, and lawmakers kept raising funds and fending off critics. Engineers told South Dakota’s US senator Peter Norbeck it would be too difficult to carve the roads he’d proposed for tourists to access the site, but Norbeck insisted they go forward: “With enough dynamite,” he told them, “anything is possible.” It’s not a slogan you’d want to print on national currency, but Borglum proved it correct, working right up until his unexpected death in 1941. Lincoln Borglum supervised the remaining work and added an extra touch: a bust of his father, which visitors pass by on their way in and out of the site.

On summer days the crowds at Rushmore are enormous, but at night you can breathe a little bit; the Park Service conducts a lighting ceremony at 9 p.m., and you can stroll around without bumping into people or walking in front of their cameras as they take photos. Light piano music plays over PA speakers; the café sells Thomas Jefferson–themed vanilla ice cream. I take a seat in the outdoor auditorium, surrounded by families passing around their smartphones to smile over the day’s vacation photos. Several of us try to take a photo of Rushmore in the dark, which proves unsuccessful to a ridiculous degree.

The ceremony starts with a short speech by a park ranger. “Mount Rushmore isn’t just a tribute to four presidents,” she says. “It’s a national symbol that represents the legacy that they leave behind, and how each and every one of us is a part of their legacy.”

She ticks down why each of the giant faces is on the mountain. Washington “represents the history of the United States, from the Revolutionary War to our role overseas today.” Jefferson, she says, represents not only westward expansion but those who “value education and free thinking.” Lincoln “was able to lay the groundwork of the abolition of slavery.” Theodore Roosevelt had been one of Borglum’s benefactors, and the sculptor probably liked the idea of putting one of his friends on the mountain, but the park ranger says TR championed the national park system.

“Mount Rushmore is for everybody,” she says. “It isn’t just a tribute to four courageous men in our country’s past. It is a reminder that day after day we follow in their footsteps. . . . And though our accomplishments may never be as great as theirs, or as nationally significant, our accomplishments matter. What you do today matters, what you do tomorrow matters.” She explains that “the lights will begin to unveil this wondrous sculpture. And as you stare up at Mount Rushmore, think about what this mountain means to you. But know that if it inspires you, makes you hopeful, angry, frustrated, or even sad, that Mount Rushmore is still for you, and that you will always be these presidents’ legacy.”

Mount Rushmore has made people angry, frustrated, and sad. The name comes from a New York attorney who was only in the Black Hills to assess nineteenth-century mining claims; the Lakota people, who lived in the area and believed the hills to be the place where their ancestors were created, called it “Six Grandfathers,” for heaven, earth, and the four cardinal directions. They have rarely been thrilled with the four giant white guys on top of their sacred place—which they had to give up to the US government less than a decade after it was promised to the Lakota for all time.†

This tension is what led to the construction of the Crazy Horse monument just minutes from Rushmore. Boston-born sculptor Korczak Ziolkowski had come to South Dakota in 1939 to work on the presidents, but he ended up working on the competing sculpture at the behest of Sioux chief Henry Standing Bear, who told him, “We would like the white man to know the red men have great heroes also.” Ziolkowski’s work, which began in 1948, has been in progress for decades. When it’s finished it will be over five hundred feet high—even higher than Rushmore.

Mount Rushmore has played host to protests, too. In 1970, the American Indian Movement set up camp atop the mountain, demanding the government return land taken for military use during World War II. In 2009, authorities arrested eleven Greenpeace activists who had snuck onto the mountain and unfurled a sixty-five-foot banner next to Lincoln’s head, calling for action on climate change. The National Park Service cut off access to the mountain and conducted 3-D scans of the sculptures, just in case the next protesters—or terrorists—brought something more explosive than a banner.

Even these critics of the mountain are part of the legacy of the Rushmore four. I can believe that we’re all part of the presidents’ legacies. But maybe it works the other way around, too. Without Terry Simpson, the museum director who showed me around William Henry Harrison’s tomb in southwestern Ohio, the ninth president might not have much of a legacy to be part of. We wouldn’t have Hoover-Ball without Herbert Hoover, but we wouldn’t remember it without the teams in West Branch that come out each summer to play it. The presidents are fodder for giant, majestic works of art, but we’re the ones who build in their images.

We couldn’t do a Mount Rushmore today. For one thing, we’d argue too much about which heads to put on top of the mountain. There have been calls at times for carving Ronald Reagan, Franklin Roosevelt, and John F. Kennedy into the mountain; some have even suggested adding nonpresidents, like Frederick Douglass, or Elvis. The mountain can’t support a fifth head, but people keep arguing about which head it is that we can’t put up there.‡

Heck, we even argue about imaginary Rushmores. LeBron James irked basketball pundits by declaring he would be atop basketball’s Mount Rushmore by the time he retired. “I’m going to be one of the top four to ever play this game,” he said, adding that “architects” would have “to chisel somebody’s face out and put mine up there.” There is no actual Mount Rushmore of basketball, and the game’s Hall of Fame has neither chisels nor a shortage of room for great players, but sports fans went at each other for weeks about whether King James belonged on “basketball’s Rushmore.” Maybe the park rangers could weave this into their talks before the lighting ceremonies. “If you think LeBron James is better than Oscar Robertson or Magic Johnson, Mount Rushmore is still for you.”

There’s been a big change in the way we honor presidents. Before the twentieth century, before broadcasting brought the voices and faces of national figures into our houses, presidents were pretty remote, so our monuments turned them into icons. Today, presidents are human. We see and hear them all the time. We know historic change doesn’t always come from what a president does or doesn’t do, and we know their personal and professional failings, sometimes better than they do. We don’t even need to build monuments to them anymore; through the presidential library system they can try to build their own. Maybe that’s why, in 2011, the government announced it would scale back a presidential commemorative coin program due to high cost and low interest. “As will shock you all,” said Vice President Joe Biden at the time, “calls for Chester A. Arthur coins are not big.”

But maybe America still has room for a presidential monument or two, just on a smaller scale. Down the road from Rushmore is Rapid City, South Dakota, which calls itself “the most patriotic city in America” and shows it with a full set of life-size presidential statues. Some of the figures are exactly what you’d expect, like Harry Truman holding up the “Dewey Defeats Truman” newspaper, or Dwight Eisenhower in his World War II general’s outfit. Some are even duplicates of works I’ve seen elsewhere: the Van Buren sculpture is the same as the one in downtown Kinderhook, New York, and I saw the Jefferson statue at a bus station in Chicago.

Others are pleasant surprises. Rapid City doesn’t portray William Howard Taft as large and jolly; instead, he’s athletic and shrewd—baseball’s first First Fan is hunched over with a baseball in his right hand; he’s ready to throw to a batter, and the gleam in his eye suggests he’s going to throw a strike. George W. Bush holds his dog, Barney, in one hand and gives a thumbs-up with the other, but with so many cars around, “43” appears to be asking for a ride. Richard Nixon sits under a tree, his hands together, pondering the intricacies of foreign policy—but the pose also makes him look like a supervillain.

The statues face each other on street corners. Jimmy Carter’s statue is waving; the wave looks as if it’s intended for Ronald Reagan, who’s across the street, while Andrew Jackson seems to watch them both from a distance: his statue reminded me of the line in “The Farmer in the Dell” about the cheese standing alone. The glum Millard Fillmore sets down his law book and peers over at Woodrow Wilson, trying to figure out what the fuss is about. The statues also interact with the surrounding buildings: Franklin Pierce, who had troubles with the bottle, stands outside a pub. Teddy Roosevelt, decked out in his Rough Rider gear, stands near a coffee shop named in his honor: Bully Blends. And the sight of John Quincy Adams and Gerald Ford next to banners proclaiming “Welcome Bikers” is as good as it gets.

There is no more space atop Mount Rushmore—the epitome of how we once looked up to our presidents. But in downtown Rapid City, where presidents are honored at our size and at our level, there’s room for eighty statues in all—plenty of room to grow.

* Gehry explained that the idea for the boyhood statue came from a speech Eisenhower gave in his home state, downplaying his wartime achievements and choosing to “speak first of the dreams of a barefoot boy” from Abilene.

† The sudden change came after white settlers discovered gold in the hills.

‡ There was barely room, in fact, for a fourth head. Jefferson was originally supposed to go on the other side of Washington, but the rock there proved inadequate for further carving. Workers had to dynamite more than a year of work and start over on George’s other side.