THOUGH NAKHT’S DIARY is a fictional story, his descriptions of Ancient Egypt are true to life. Hatshepsut really did rule Egypt 3,500 years ago (one of only three native female kings in Ancient Egyptian history), and corrupt officials often let tomb robbers escape justice. However, Nakht’s story touches on only a tiny part of a civilization that flourished on the banks of the Nile for more than 5,000 years.

What we know about Ancient Egypt comes from objects that archaeologists have found buried and from ancient writings on documents, monuments, and tombs.

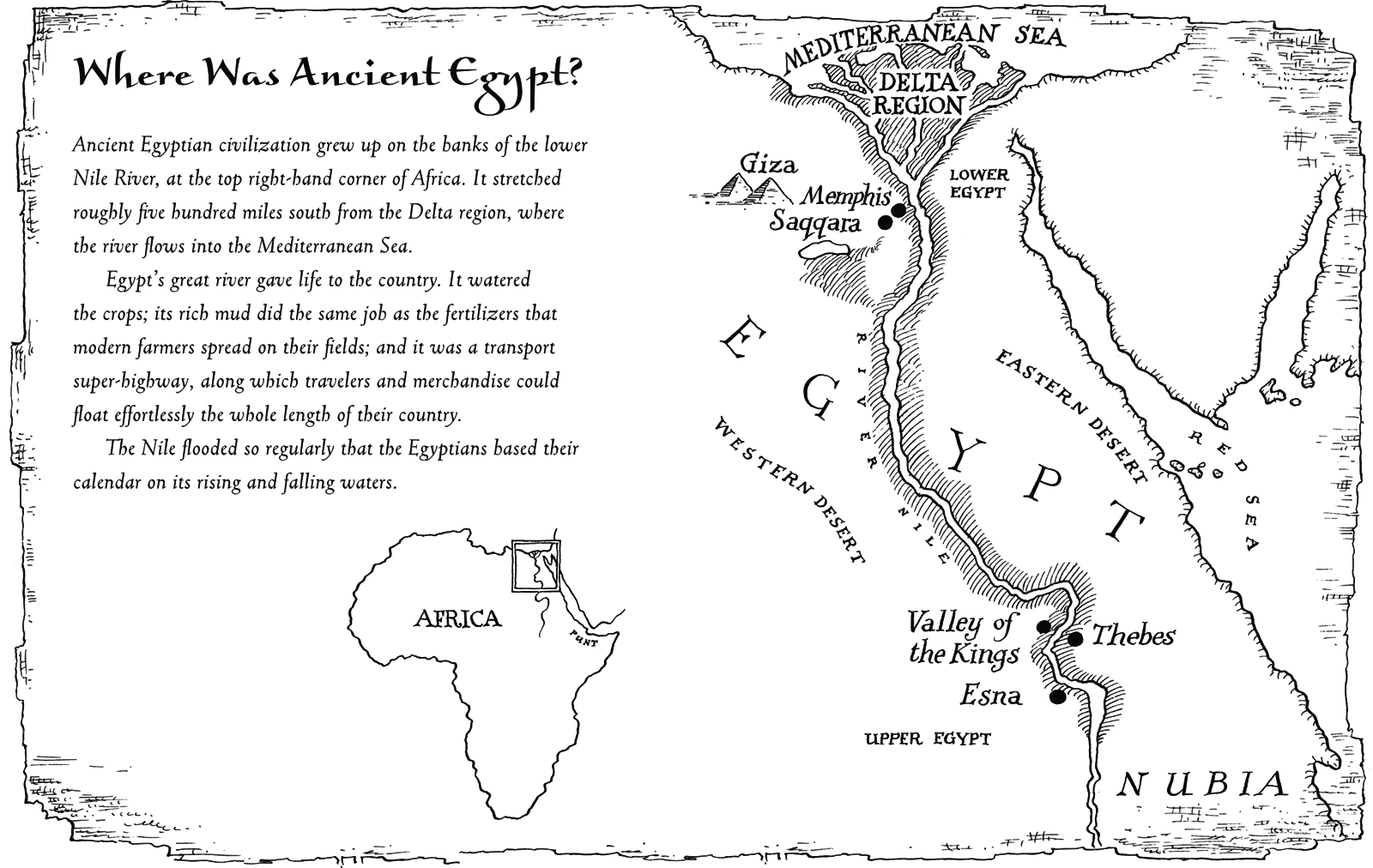

Egypt is a desert. The air is very dry, and away from the Nile, the ground is parched. The dryness has preserved objects buried in the sand and in tombs cut into the rock or built from stone and brick.

However, the banks of the Nile were the center of most of life in Ancient Egypt. These areas flooded each year, and the water destroyed many of the objects that archaeologists would love to study.

What Survived?

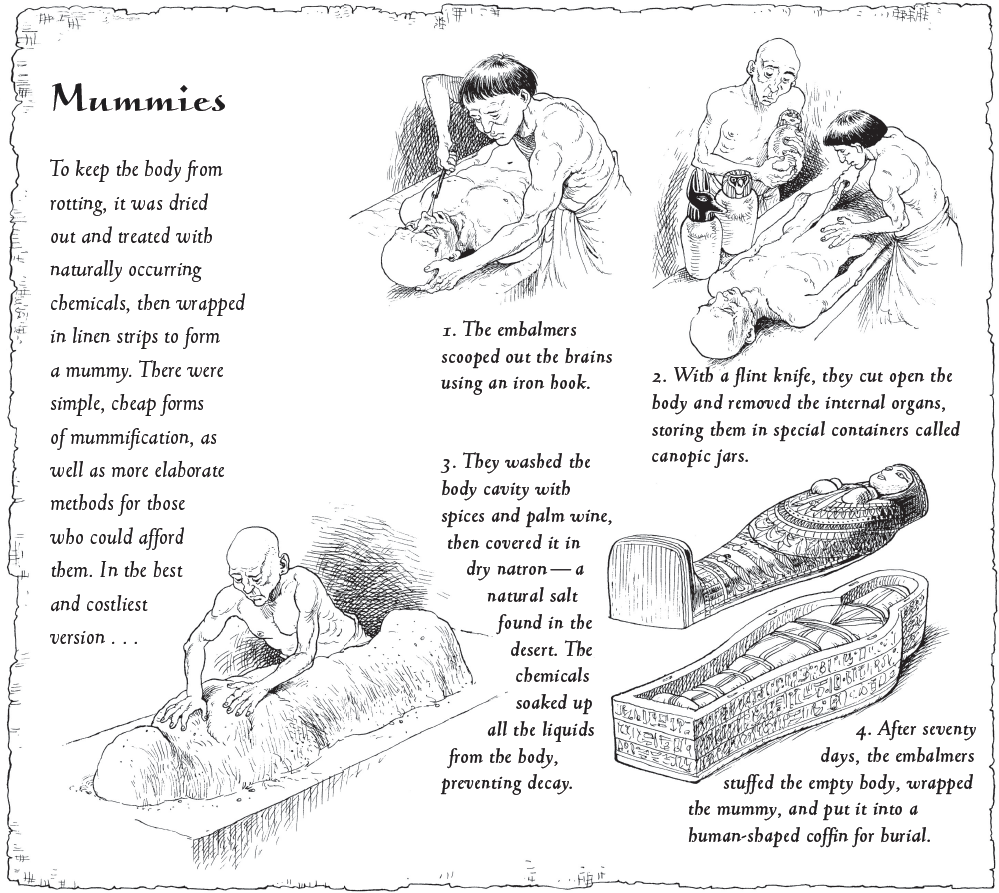

The part of Ancient Egyptian life that we know a great deal about is death. The ancient Egyptians attached huge importance to it. They went to a lot of trouble to preserve the bodies of the dead and performed elaborate ceremonies in their honor. Inscriptions on tomb walls and in special Books of the Dead explain these rituals in minute detail.

Fortunately, one particular part of the Egyptian obsession with death has helped archaeologists in their struggle to re-create the past: the custom of burying along with the dead the things they might need in the afterlife (see here). Since people believed that the needs of the dead were not very different from the needs of the living, tombs were stacked with furniture, food, and many other personal objects — or with models of these things. So tombs are a major source of information about ancient everyday life.

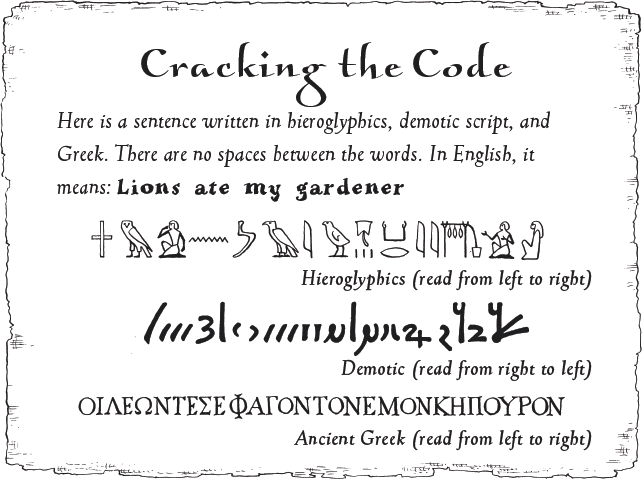

The Rosetta Stone

The inscriptions that archaeologists study on tomb walls are mostly written in hieroglyphics — a form of picture writing. But for many years they had no idea what the pictures represented. The meaning of the hieroglyphics remained a mystery until the end of the 1700s and the discovery of a stone at the Egyptian town of Rosetta. This unique stone was inscribed with hieroglyphics and with Greek and demotic (another Egyptian script). Archaeologists could read Greek and soon realized that all three inscriptions said the same thing. They had cracked the code and could now begin to translate hieroglyphic and demotic writing accurately.

Egyptian Society

Ancient Egyptian society was organized like a pyramid. At the very tip was the king. The king was always a man — even when “he” was a woman. Hatshepsut is shown dressed in the same way as male kings, even wearing a false beard.

The Egyptians believed the king was not just their ruler but also a god. They believed that the king’s power had no limits and that he knew and controlled everything, including the natural world.

It was the king’s job to look after all Egypt’s people. He was in charge of the army, the courts and justice system, the temples and religion.

Supporting the king was a small group of officials. Many of them were relatives of the king. These people made up the Egyptian nobility.

Below these noblemen were scribes, like Nakht’s father. Scribes weren’t as wealthy as the nobles, but they were well off.

Scribes did everything needed to keep the country running, including collecting taxes, enforcing the law, and arranging for food handouts when there was a famine. Each scribe was a specialist who took care of one specific kind of task.

At these two high levels in the pyramid of power, there were also religious officials — priests and high priests — who organized the many temple rituals and ceremonies.

Lower in status than the scribes and priests were Egypt’s craftsmen. These skilled workers created the fine ornaments and luxury goods that the king and those around him used. There were more craftsmen than scribes, but the craftsmen were hugely outnumbered by those beneath them — Egypt’s peasant farmers.

Much of what the farmers produced was paid to the king in taxes — so their grain or livestock went to feed the scribes, priests, and nobility.

At the very bottom of the pyramid were the slaves. They acted as household servants or farm laborers. Many slaves were foreigners, captured in battle by Egypt’s armies. Others were Egyptians who had sold themselves into slavery to pay off debts. It wasn’t just rich scribes or nobles who owned slaves — even common Egyptians could afford them.

The Gods

Egyptians worshipped many gods, but not all had equal status. The least important were house gods, some of whom had special responsibilities or guarded against particular dangers.

More important state gods had temples dedicated to them, where priests performed rituals in their honor. These gods kept disorder and chaos at bay. The Egyptians were so concerned about leading proper, well-ordered lives that they even had a word for it: maat. Though it’s impossible to translate into a single English word, maat means the right way to do things; order, freedom from chaos; truth and balance. Egyptian people valued maat very highly, and it was important to respect the gods in order to preserve maat.

AMUN-RE

Before Hatshepsut’s time, the sun god, Re, merged with another god, Amun. The new god, Amun-Re, was the king of Egypt’s gods.

ANUBIS

The god of the dead, Anubis guarded mummies.

HAPY

Egyptians believed Hapy was responsible for the Nile’s annual floods.

ISIS

The goddess Isis was worshipped for her protective power, particularly her ability to guard children.

KHNUM

The guardian of the source of the Nile.

NUT

The sky goddess, Nut was usually shown stretching over the world, with her hands and feet touching the earth.

OSIRIS

The god of death, but also of fertility and rebirth. His death and resurrection came to stand for the annual cycle of crop growth.

PTAH

The local guardian god of Memphis, he was believed to have shaped all living beings on a potter’s wheel and was the protector of craftspeople.

SOBEK

In Egyptian myth, the Nile’s waters were made from the sweat of this crocodile god.

THOTH

Shown as either a baboon or an ibis, Thoth was the god of writing and knowledge.

Life after Death

The need for maat did not end with death, for Egyptians believed in an afterlife. The afterlife could last forever, but only if the dead person’s family performed all the right rituals, filled the tomb with the correct equipment, and, most important of all, took care to preserve the body.

Tombs

After elaborate funeral ceremonies, Egyptian people buried the mummified corpse. Those who could afford it dug an underground tomb big enough to contain the coffin and other equipment needed on the journey to the afterlife. Above it, they constructed a kind of chapel, where living relatives could pray and make offerings to the dead.

Pyramids

The grandest of all memorials to the dead were the pyramids. Pyramid building began about 4,700 years ago. By the time it ended, 1,000 years later (around 200 years before Nakht was born), there were eighty or so pyramids on the desert’s edge on the west bank of the Nile.

Robbers

Pyramids protected the precious objects entombed with the kings inside but weren’t as secure as modern safes and strong rooms. All were robbed eventually.

Tomb robbers forced Egypt’s rulers to look for better ways of protecting their dead, and they eventually decided that secrecy was the answer. By about 1500 BC they had begun cutting tombs into rock cliffs in the Valley of the Kings, near Thebes, and then building funeral chapels some distance away.

Even these hidden graves were often robbed, but one, the tomb of Tutankhamun (1336–1327 BC) escaped complete destruction. When it was opened in the early twentieth century, the fabulous gold treasures found inside astonished the world.