El diablo no duerme.

The devil doesn’t sleep.

The peach trees are in bloom as we approach Magdalena Espinosa’s house. The noonday sun shines down on the brilliant blossoms, made all the more striking because the tree stands beside her bright turquoise-blue garage door.

We’ve heard Magdalena’s health is failing and want to pay a visit. It’s been a half year since our memorable time with her and Esequiel here. But April is the cruelest month, as T. S. Eliot said, and it seems to me to be truer every spring. It’s not likely Magdalena will last out the change in season, and we aren’t meant to see her today to say our farewells. She’s slipping away and is already inaccessible to us.

Mom and I drive away from La Cuchilla in the somber spring sunlight and decide to visit the oratorio, the small chapel dedicated to San Buenaventura, which for many decades was the center of community celebration and mourning on the Plaza del Cerro. But on the way I detour down a little-used road to show Mom an even humbler site, a small shrine in a field. It’s a simple structure, perhaps six feet tall, made of concrete painted white and roofed with fiberglass pinned down by river rocks. A defunct red Toyota is parked up against one of the shrine’s crumbling walls.

Blue trim borders the opening of the sanctuary, framing an interior space filled with religious paraphernalia: prints of the Virgin Mary; votive candles bearing images of Christ, Mary, and several saints; and a calendar adorned with an image of the Virgin of Guadalupe and a devotional prayer. Strings of Christmas lights, plastic strands of evergreen boughs, and other ornaments are draped over and around these items. The newness of some of the objects reveals the place is visited frequently, even though it is weathering away.

Seeking access beyond the fence to get closer to the shrine, I knock on the door of the house nearby. No response. I’m waiting when a large, jacked-up four-wheel-drive truck pulls up, its windows darkly tinted. The door opens, and a woman in a black dress steps down to a gleaming chrome step, then to the ground. Perhaps in her midseventies, she has lustrous, raven-black hair. Fine crow’s-feet dance around her bright green eyes, the only wrinkles in her otherwise smooth bronze skin; they add a touch of elegance to her graceful demeanor. She smiles and beams a look that utterly enchants me. Her daughter and son-in-law exit the truck and join her in greeting me. They’re all delighted I would like to photograph their little shrine, but the woman refuses me a picture of herself. No amount of charm in Spanish or English can sway her.

I spend a few minutes at the shrine, and, mindful of the admonition I had received from Juan Trujillo to be sure to pray when visiting holy places, I pause for a moment of silence. Mom watches from the car. A prayer I learned from her and Grandma comes to me:

Con Jesús me acuesto

Con Jesús me levanto

Con la virgen María y el Espíritu Santo . . .

And along with that comes a joke both Grandma and Mom used to tell. It goes something like this:

It seems there was a young man in the plaza who wasn’t quite right in the head. (When he or similar characters came up in conversation, Grandma had several dichos at hand, such as “Le falta un real para el peso y la mitad de la semana—He is a quarter short of a dollar and half of the week” or “Le falta un tornillo.—He’s missing a screw.” Mostly, though, she would characterize such unfortunate souls as medio medio.) One night as he and his mother knelt to pray, they recited the prayer I just recalled, which translates as:

“With Jesus I lay down to rest

With Jesus I rise

With the Virgin Mary and the Holy Spirit—”

At which point the young man interjected: “¡Embustera! ¡Se acuesta con papá y se levanta con él también!—Liar! You lay down with Dad, and you get up with him, too!”

When Grandma told this little story, she would conclude with the dicho “¡Los locos y los chiquitos dicen la verdad!—Crazy people and little children tell the truth!”

My laughter beside the shrine isn’t exactly the kind of reverence Juan Trujillo had hoped for when he lectured me, but it somehow doesn’t seem inappropriate. Mom and I share a good giggle over the old joke as we drive away toward the Oratorio de San Buenaventura at the Plaza del Cerro.

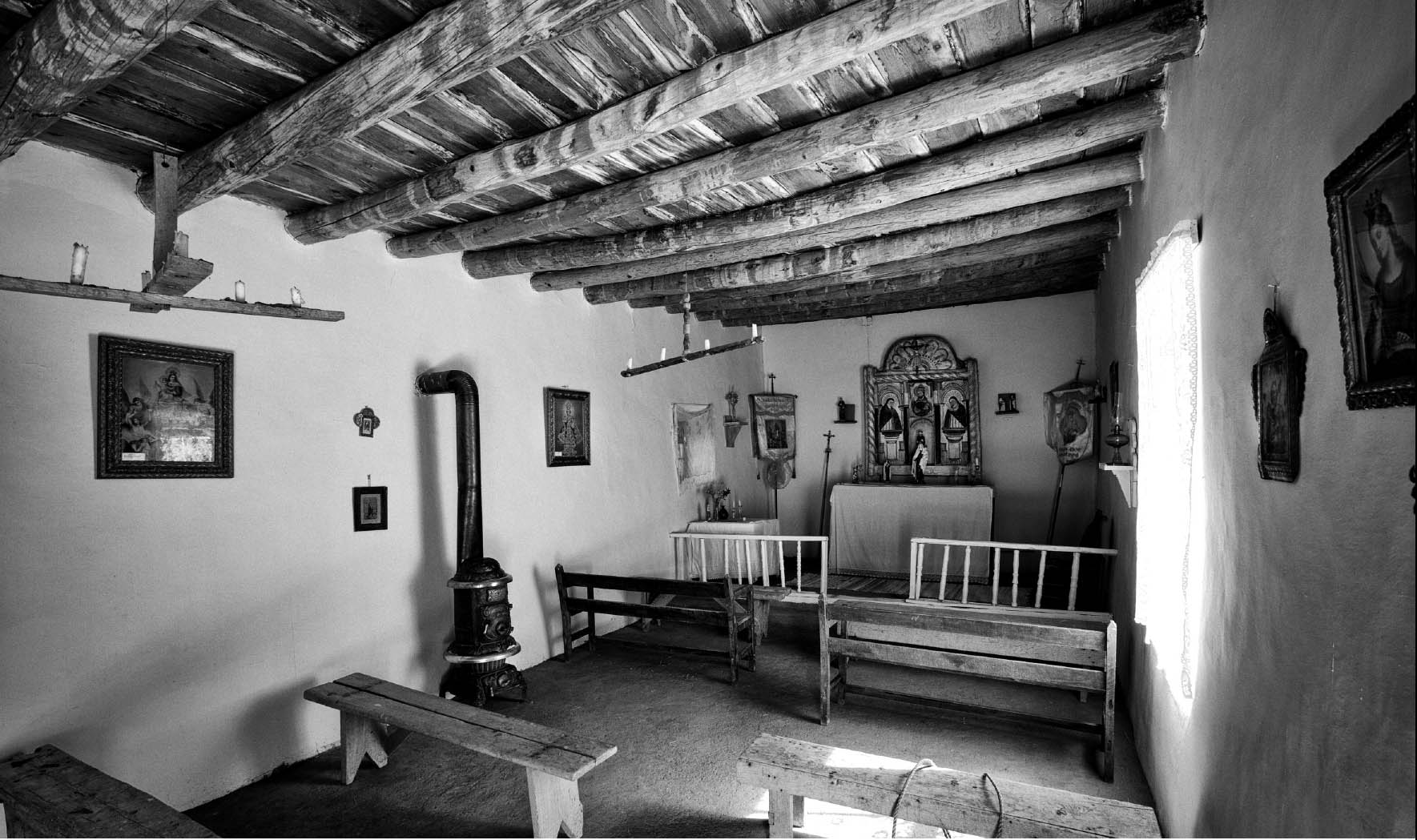

It strikes me that in all the times I’ve visited the capilla on the Plaza del Cerro, I’ve only entered once with my mother—on the day the priest blessed the new bell we had painstakingly installed. Now it’s just the two of us here, and the plaza is extraordinarily quiet. I open the padlock securing the door and help Mom step up into the dark, cool interior of the capilla. An even greater stillness envelops us.

The oratorio is not a freestanding structure like other capillas in the valley. It’s simply one of the many rooms comprising the perimeter of the Plaza del Cerro, a room dedicated by Pedro Ascencio Ortega to the patron saint of the Plaza del Cerro, San Buenaventura. A small bulto (statue) of the santo patrón—a replacement for the stolen original—presides over the silence, his figure ensconced in a recess at the center of an elegant retablo de altar (altar screen) painted by one of nineteenth-century New Mexico’s most prolific and well-known santeros, Rafael Aragón. Although the plaza wasn’t built until the 1780s or so, people in this part of the valley had been devoted to San Buenaventura long before. Some of the early documents in our collection mention Buenaventura as the santo patrón of the area. Indeed, a 1758 land sale and the 1766 paper dividing the land of Antonia Lopes—the one mentioning the blue rock—calls this part of the valley “el partido de San Buena Bentura—the jurisdiction of San Buenaventura.”

San Buenaventura, whose feast day is July 15, is an uncommon figure in the iconography of northern New Mexico. His reputation in the Catholic world resides more in his intellectual appeal than in supernatural powers. People do not petition him for a specific kind of intercession. Rather, he is recognized as a great scholar and mystic and an early, central figure in the Franciscan order. I often wonder why he was chosen as the patron saint of this small plaza. In New Mexico, he is the patron saint of few places, among them Cochití Pueblo and the abandoned Las Humanas mission. Perhaps he was chosen because the plaza was founded on his feast day, but there is no document that gives a date.

Mom sits quietly in the oratorio on a sagging bench fashioned of roughhewn boards joined without nails. Above her, handmade arañas (simple wooden chandeliers) hang motionless in the still air, their candles reduced to lumps of wax that haven’t been molten for many years. She studies the altar screen, the dusty linen on the altar, the carved figure of San Buenaventura, secure in its small nicho.

Pedro Asencio Ortega’s will describes in detail the contents of this room, which at the time of his death was one of the rooms in his house. He enumerates items in the chapel, including one of the arañas hanging from the ceiling. (A cousin of mine held the original copy of Ortega’s will, but it seems to have been lost.)

“Look, the banners of the Carmelitas are still here,” she says, pointing to the plastic-shrouded standards leaning in the corners, each emblazoned with the name of the women’s confraternity that used to maintain this place: Cofradía de Nuestra Señora del Carmen—the Confraternity of Our Lady of Mount Carmel. One includes a supplication: Ruega por nosotros.—Pray for us.

I’m not sure why the Carmelitas, as the women’s group used to be called, chose this capilla for their meeting place. It would seem the chapel dedicated to Señora del Carmen, in La Cuchilla, would have been the more natural choice. But for many decades the Carmelitas held their meetings here and each May led the plaza residents in a celebration of the Mes de María, the Month of Mary.

“I was a flower girl for the Carmelitas when they walked around the plaza saying the rosary,” Mom says, recalling the annual procession on the last day of May. “Tila and Urbanita and all the little girls and I would go up in the hills and along the ditches to gather flowers, and then we’d walk ahead of the women and throw the flowers on the path in front of them. We felt very special having a role to play in the procession.”

The Carmelitas maintained the oratorio for most of the twentieth century, led by my great-grandfather’s spinster sister, Bonefacia Ortega. (As expressed in the dicho for a woman who never marries, “Se quedó para vestir santos.—She was left to dress the saints.”) She was one of a long line of Ortegas to take a leadership role in maintaining the oratorio. But in fact the care for the place has always been a community affair. We have notes from the late 1800s listing the names of people who contributed limosnas, or alms, for the upkeep of the place. For their contributions, most offered dos reales (a quarter) or ten or twenty cents; but some didn’t have money and instead offered a handful of tobacco, a half a ristra of chile, a fanega (roughly a bushel) of wheat, or a couple of almudes (half fanegas) of alverjones (chickpeas).

In a license issued in 1860, Archbishop “Juan B. Lamy” (i.e., Jean-Baptiste Lamy, the first archbishop of Santa Fe) authorized the Carmelitas to collect alms. Among our papers is a handwritten copy of the original document, penned by Juan de Jesús Trugillo, the priest in Santa Cruz de la Cañada.

The plaza community contributed to the upkeep of the chapel in many ways. Looking up to the ceiling made of hand-split pine boards, I note the signatures of men who helped renovate the place in 1873. Notably absent are women’s names, even though they certainly contributed to the work. In those days, women usually took charge of the plastering, and they probably fed the men working on the roof as well.

The oratorio occasionally served as a place for meetings of Los Hermanos. It may, in fact, originally have been created as a formal morada. Although the architecture of moradas varies from community to community, many of them are bipartite in layout, with one section devoted to everyday activities and the other, called an oratorio, reserved for prayer, singing, and the other Hermanos rituals. (The Hermanos are best known for performing rituals during Holy Week, although the organization serves many other social functions as well.) Pedro Asencio Ortega married Bernardo Abeyta’s daughter. Bernardo was the patron who built the santuario and also was renowned as an hermano mayor in the brotherhood. Pedro Asencio’s son José Ramón Ortega y Abeyta served in the brotherhood and took care of the oratorio. Furthermore, the Carmelitas were closely affiliated with Los Hermanos, acting as a female counterpart to the men’s group and assisting with many its activities. All this makes me wonder if the oratorio originally was a meeting place for Los Hermanos.

Mom reads the names on the ceiling aloud.

“Jose Patricio Trujillo . . . Jose Pantalion Jaramillo . . . Jose Candelario Trugillo . . . Jose Guadalupe Ortega . . . Jose Eugenio Martines . . . Jose Livio Ortega . . . Jose Agapito Ortega . . . Jose Anastasio Jaramillo . . . Jose Antonio Martines . . .”

To his signature, José Antonio Martines added the notation: “En el año de 1873 se renebo la casa de San Buena Bentura.—In the year of 1873, the house of San Buenaventura was renovated.”

Mom is very well versed in the genealogy of the plaza families, but even so she can’t connect all of the names with lineages she knows. She does place Agapito, though.

“Oh, Agapito—that was Doña Socorro’s husband—remember him? Socorro was Trinidad’s mother. Trinidad Ortega was married to Eufelia. They lived right across the road from Tía Melita. I remember Socorro. She was from the generation of the old-timers who were around when I was little.”

Recalling one of the documents in the family collection, I ask, “Remember the letter from Domingo Ortega to his father, Gerbacio? He was writing home from Conejos, Colorado, announcing the birth of a daughter, María Petra del Socorro? Is that Agapito’s wife?”

“No, Doña Socorro was not related to us,” Mom answers. “María Petra del Socorro was Domingo Ortega’s daughter. They eventually settled in Mora. Doña Socorro was Ortega because of her marriage to Agapito Ortega, who was related to that other branch of the Ortegas—not ours—some way. Era harina de otro costal.—She was flour from another sack,” Mom says, citing a dicho.

The names on the ceiling and on the lists of almsgivers offer snapshots of who lived here in the late nineteenth century, before Protestant missionaries showed up to challenge the religious orthodoxy of the plaza. Soon after the arrival of the first minister, the caretaker of the oratorio, José Ramón Ortega y Abeyta (not to be confused with his neighbor, my ancestor José Ramón Ortega y Vigil), converted to Protestantism and handed over the keys to the oratorio to Tía Bonefacia, sometime around 1900. The Reformation had come to Chimayó.

We sit quietly in the oratorio for some time, immersed in the peculiar, solemn spell that always envelops it. Mom reminds me that at least one of our relatives rests here, buried in the dirt floor beneath our feet. One of the papers Mom keeps names the child, Gumersinda Ortega, who died in 1909 at the age of three. Grandma mentioned her often, along with the names of the other deceased siblings in her family: Corina, Antonio, Sabinita. Children were often buried here in the oratorio, as this was considered holy ground, suitable for interring children who died without the benefit of last rites. The sanctified ground would secure the angelitos’ passage to join the celestial saints whose visages watch over this place.

We study the fine strokes in Aragón’s retablo and the simplicity and elegance of the small religious prints on the walls, hung in handworked tin frames at random intervals here and there. The plain white walls, the dark steel woodstove, the wooden railing in front of the altar—everything here bespeaks a powerful but humble piety and a careful attention to maintaining an atmosphere of sacredness.

Interior, Oratorio de San Buenaventura, 2009.

The only jarring element in the tranquil and perfectly composed scene is the severed rope that was connected to the bell now absent from the crooked belfry on top of the oratorio. The rope lies on a bench where it fell when the thieves cut it and pitched the heavy bell off the roof—no easy feat and one that took considerable determination to pull off. The limp, crudely cut rope with a loop on one end lies there like a used hangman’s noose. This violation of sacred space and the spirit of community is a pitiful reminder of the tragic decline of this plaza. The oratorio is still here, looking almost exactly as it did 150 years ago, but we’re none too sure how many more it will last.

And we’ve heard that lately a nearby resident has been gleefully ringing a bell in his backyard, his delight apparent in the loud laughter accompanying the peals.

Me dijo del paladar al diente.

She spoke to me from the palate to the tooth. (Said when somebody tells you something they don’t really mean.)

Me quiere jugar un dos por cuatro.

He wants to give me two for four. (He wants to cheat me.)

Me quiere tapar el sol con la mano.

He wants to cover the sun with his hand. (He wants to make a fool out of me.)

Me siento como cabra en corral ajeno.

I feel like a goat in someone else’s corral. (I feel out of place.)

Muerto el perro, se acaba la rabia.

The rabies is gone after the dog is dead. (When a person dies, his anger dies with him.)

No es el león como lo pintan.

The lion is not the way they paint him to be.

No hay peor sordo que él que no quiere oír.

There is no deaf person worse than one who doesn’t want to hear.

No le esconde la vela a nadie.

She will not hide the candle for anyone. (Said of someone who can’t keep a secret.)

There is no jealousy in Margaret. (Said when someone doesn’t mind what another is doing because she is guilty of doing the same thing.)

No sabe ni lo que suena atrás.

He doen’t even know what is making noise behind him. (He’s oblivious to what is going on.)

No tiene crianza, ni moralidad, ni pelo en la lengua.

She doesn’t have respect, morality, nor hair on her tongue. (Said of a disrespectful, immoral, and vile-speaking person.)

No vale ni un cero a la izquierda.

He’s not worth even a zero to the left side.