Chapter 9

THE TRADING DESK

It’s not like I’m making pitching changes during the game.

—Billy Beane, quoted in the Boston Herald, January 16, 2003

IT WAS LATE JULY, which is to say that Mike Magnante had picked a bad time to pitch poorly. “Mags,” as everyone called him, had come in against Cleveland in the top of the seventh with two runners on and a three-run lead. The first thing he did was to walk Jim Thome—no one could blame him for that. He then gave up a bloop single to Milton Bradley and the inherited runners scored—just plain bad luck, that. But then he threw three straight balls to Lee Stevens. Stevens dutifully took a strike, then waited for Mags to throw his fifth pitch.

The first question Billy Beane will ask Art Howe after the game is why the fuck he’d brought Magnante into a tight game. In tight situations Art was supposed to use Chad Bradford. Bradford was the ace of the pen. So that it would be clear in Art’s head, Billy had instructed him to think of Bradford as “the closer before the ninth inning.” Art’s first answer about Magnante was that he thought Mags, the lefty, would be more effective than Bradford, the righty, against a left-handed slugger like Thome. Which is nuts, since Mags hasn’t gotten anyone out in weeks and Bradford has been good against lefties. Art’s second answer is that Billy put Mags on the team, and if a guy is on the team, you need to use him. Art won’t say this directly to Billy but he’ll think it. The coaching staff had grown tired of hearing Billy holler at them for using Magnante. “The guy has got braces on both legs,” says pitching coach Rick Peterson. “We’re not going to use him as a pinch runner. If you don’t want us to use him, trade him.”

Mike Magnante goes into his stretch and looks in for the signal. He just last month turned thirty-seven, and is four days shy of the ten full years of big league service he needs to collect a full pension. It’s not hard to see what’s wrong with him, to discern the defect that makes him available to the Oakland A’s. He is pear-shaped and slack-jawed and looks less like a professional baseball player than most of the beat reporters who cover the team. But he has a reason to hope: his history of pitching better in the second half than the first. The team opened the season with three lefties in the bullpen, which is two more than most clubs carried. A month ago they’d released one, Mike Holtz, and two days ago sent down the other, Mike Venafro. The story Mike Magnante told himself on the eve of July 29, 2002, was that he hadn’t pitched often enough to find his rhythm. He’d go a week when he made only three pitches in a game. With the other Mikes gone, he finally had his chance to find his rhythm.

He makes an almost perfect pitch to Lee Stevens, a fastball low and away. The catcher is set up low and outside. When you saw the replay, you understood that he’d hit his spot. If he’d missed, it was only by half an inch. It’s the pitch Mike Magnante wanted to make. Good pitch, bad count. The ball catches the fat part of the bat. It rises and rises and the two runners on base begin to circle ahead of the hitter. Mags can only stand and watch: an opposite field shot at night in Oakland is a rare, impressive sight. It is Lee Stevens’s first home run as a Cleveland Indian. By the time the ball lands, the first and third basemen are closing in on the mound like bailiffs, and Art Howe is on the top of the dugout steps. He’s given up five runs and gotten nobody out. It wasn’t the first time that he’d been knocked out of the game, but it wasn’t often he’d been knocked out on his pitch. That’s what happens when you’re thirty-seven years old: you do the things you always did but the result is somehow different.

The game is effectively over. Chad Bradford will come on and get three quick outs, too late. The Indians’ own left-handed relief pitcher, Ricardo Rincon, strikes out David Justice on three pitches and gets Eric Chavez to pop out on four. The contrast cast Mags in unflattering light. The A’s had the weakest left-handed relief pitching in the league and the Indians had some of the strongest. To see the difference, Billy Beane didn’t even need to watch the game.

HAVING JUST FINISHED an enthusiastic impersonation of a baseball owner pretending to be a farm animal receiving a beating, Billy Beane rose back into his desk chair and waited, impatiently, for Mark Shapiro to call. Mark Shapiro was the general manager of the Cleveland Indians.

When Billy sat upright in his office, a few yards from the Coliseum, he faced a wall covered entirely by a white board and, on it, the names of the several hundred players controlled by the Oakland A’s. Mike Magnante’s name was on that board. Swiveling around to his rear he faced another white board with the names of the nearly twelve hundred players on other major league rosters. Ricardo Rincon’s name was on that board. At this point in the year Billy didn’t really need to look at these boards to make connections; he knew every player on other teams that he wanted, and every player in his own system that he didn’t want. The trick was to persuade other teams to buy his guys for more than they were worth, and sell their guys for less than they were worth. He’d done this so effectively the past few years that he was finding other teams less eager to do business with him. The Cleveland Indians were not yet one of those teams.

Waiting for Shapiro to call him, Billy distracted himself by paying attention to several things at once. On his desk was the most recent issue of Harvard Magazine, containing an article about a Harvard professor of statistics named Carl Morris (the Bill James fan). The article explained how Morris had used statistical theory to determine the number of runs a team could expect to score in the different states of a baseball game. No outs with no one on base: 55. No outs with a runner on first base: 90. And so on for each of the twenty-four possible states of a baseball game. “We knew this three years ago,” says Billy, “and Harvard thinks it’s original.”

He shoves a wad of tobacco into his upper lip, then turns back to his computer screen, which displays the Amazon.com home page. In his hand he’s got a review he’s ripped out of Time magazine, of a novel called The Dream of Scipio, a thriller with intellectual pretension. He reads the sentence of the review that has made him a buyer: “Civilization had made them men of learning, but in order to save it they must leave their studies and become men of action.” As he taps on his computer keyboard, the television over his head replays Mike Magnante’s home run ball of the night before. The Oakland A’s announcers are trying to explain why the Oakland A’s are still behind the Anaheim Angels and the Seattle Mariners in the division standings. “The main reason this team is trailing in the American League West,” an announcer says, “is that they haven’t hit in the clutch, they haven’t hit with guys in scoring position.” Billy drops the book review, forgets about Amazon, and reaches for the TV remote control. Of the many false beliefs peddled by the TV announcers, this fealty to “clutch hitting” was maybe the most maddening to Billy Beane. “It’s fucking luck,” he says, and faces around the dial until he finds Moneyline with Lou Dobbs. He prefers watching money shows to watching baseball anyway.

On the eve of the trading deadline, July 30, he was still pursuing two players, and one of them is the Cleveland Indians’ left-hander, Ricardo Rincon. At that very moment, Rincon is still just a few yards away, inside the visitor’s locker room, dressing to play the second game of the three-game series against the Oakland A’s. The night before, he’d only thrown seven pitches. His arm, no doubt, felt good. The Cleveland Indians have given up any hope of winning this year, and are now busy selling off their parts. “The premier left-handed setup man is just a luxury we can’t afford,” said Indians’ GM Shapiro. Shapiro has shopped Rincon around the league and told Billy that there is at least one other bidder. Billy has found out—he won’t say how—that the other bidder is the San Francisco Giants and that the Giants’ offer may be better than his. All Billy has offered the Indians is a minor league second baseman named Marshall MacDougal. MacDougal isn’t that bad a player.

Anyone seeking to understand how this team with no money kept winning more and more games would do well to notice their phenomenal ability to improve in the middle of a season. Ever since 1999 the Oakland A’s have played like a different team after the All-Star break than before it. Last year they had been almost bizarrely better: 44–43 before the break, 58–17 after it. Since the All-Star Game was created, in 1933, no other team had ever won so many of its final seventy-five games.*

The reason the Oakland A’s, as run by Billy Beane, played as if they were a different team in the second half of the season is that they were a different team. As spring turned to summer the market allowed Billy to do things that he could do at no other time of the year. The bad teams lost hope. With the loss of hope came a desire to cut costs. With the desire to cut costs came the dumping of players. As the supply of players rose, their prices fell. By midsummer, Billy Beane was able to acquire players he could never have afforded at the start of the season. By the middle of June, six weeks before the trading deadline, he was walking into Paul DePodesta’s office across the hall from his own and saying, “This is the time to make a fucking A trade.” When asked what was meant by a “Fucking A trade,” he said, “A Fucking A trade is one that causes everyone else in the business to say ‘Fucking A.’”

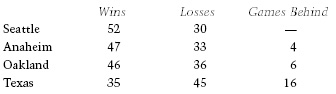

By late July—the trade deadline was July 31—Billy’s antennae for bargains quivered. Shopping for players just before the deadline was like shopping for used designer dresses on the day after the Oscars, or for secondhand engagement rings in Reno. His goal at the start of the season had been to build a team good enough to remain in contention until the end of June. On July 1, the American League West standings looked like this:

Having kept the team close enough to hope, Billy could now go out and shop for whatever else he needed to get to the play-offs. When he set off on this shopping spree, he kept in mind five simple rules:

1. “No matter how successful you are, change is always good. There can never be a status quo. When you have no money you can’t afford long-term solutions, only short-term ones. You have to always be upgrading. Otherwise you’re fucked.”

2. “The day you say you have to do something, you’re screwed. Because you are going to make a bad deal. You can always recover from the player you didn’t sign. You may never recover from the player you signed at the wrong price.”

3. “Know exactly what every player in baseball is worth to you. You can put a dollar figure on it.”

4. “Know exactly who you want and go after him.” (Never mind who they say they want to trade.)

5. “Every deal you do will be publicly scrutinized by subjective opinion. If I’m [IBM CEO] Lou Gerstner, I’m not worried that every personnel decision I make is going to wind up on the front page of the business section. Not everyone believes that they know everything about the personal computer. But everyone who ever picked up a bat thinks he knows baseball. To do this well, you have to ignore the newspapers.”

His complete inability to heed Rule #5 Billy Beane compensated for by fanatically heeding the other four. His approach to the market for baseball players was by its nature unsystematic. Unsystematic—and yet incredibly effective.

The absence of cash is always a problem for a man on a shopping spree. Ricardo Rincon would be owed $508,000 for the rest of the season, and that is $508,000 the Oakland A’s owners won’t agree to spend. To get Rincon, Billy must not only persuade Indians GM Shapiro that his is the highest bid; he must find the money to pay Rincon’s salary. Where? If he gets Rincon, he doesn’t need Mike Magnante. No one else does either, so he’s unlikely to save money there. No matter what he does, the A’s will wind up eating Magnante’s salary. But he might well be able to move Mike Venafro, the low-budget left-handed reliever he had just sent down to Triple-A. Venafro is a lot younger than Magnante. Other teams might be interested in him.

This gives Billy an idea: auction Mike Venafro to teams that might be competing with him for Ricardo Rincon.

He knows that the San Francisco Giants are after Rincon. He knows also that the Giants don’t have much to spend, and that, if offered a cheaper option, they might be less inclined to stretch for Rincon. “Let’s make them skinnier,” he says, and picks up the phone and calls Brian Sabean, the GM of the Giants. He’ll offer Venafro to the Giants for almost nothing. In a stroke he’ll raise cash he needs to buy Rincon (because he won’t have to pay Venafro’s salary) and possibly also reduce his competitor’s interest in Rincon, as they’ll now see they have, in Venafro, an alternative.

Brian Sabean listens to Billy’s magnanimous offer of Mike Venafro; all Billy wants in return is a minor league player. Sabean says he’s interested. “Sabes,” Billy says, after laying out his proposal, “I’m not asking for much here. Think it over and call me back.”

The moment he hangs up he calls Mark Shapiro, current owner of Ricardo Rincon, and tells him that he has the impression that the market for Rincon is softening. Whoever the other bidder is, he says, Shapiro ought to make sure his offer is firm.

As he puts down the phone, Paul pokes his head into the office. “Billy, what about the Mets on Venafro? Just to have options.” Sabean is the master of the dry hump. Sabean is always expressing what seems like serious interest in a player, but when it comes time to deal, he becomes less serious.

“The Mets could be after Rincon,” says Billy.

The phone rings. It is Mark Shapiro, calling right back. He tells Billy that, by some amazing coincidence, the other buyer for Rincon has just called to lower his offer. Billy leans forward in his chair, chaw clenched in his upper lip, as if waiting to see if a fly ball hit by an Oakland A will clear the wall. He raises his fist as it does. “I just need to talk to my owner,” he says. “Thanks, Mark.”

He puts down the phone. “We have a two-hour window on Rincon,” he says. He now has a purpose: two hours to find $508,000 from another team, or to somehow sell his owner on the deal. Never mind that his owner, Steve Schott, has already said that he won’t spend the money to buy Rincon. He shouts across the hall. “Paul! What’s left on Venafro’s contract?”

“Two hundred and seventy thousand, eight hundred and thirty-three dollars.”

He does the math. If he unloads Venafro, he’ll still need to find another $233,000 to cover Rincon’s salary, but he isn’t thinking about that just yet. His owners have told him only that they won’t eat 508 grand; they’ve said nothing about eating 233 grand. He has two hours to find someone who will take Venafro off his hands. The Mets are a good idea. Billy picks up the phone and dials the number for Steve Phillips, the general manager of the Mets. A secretary answers.

“Denise,” says Billy, “Billy Beane, Vice President and General Manager of the Oakland Athletics. Denise, who is the best-looking GM in the game?” Pause. “Exactly right, Denise. Is Steve there?”

Steve isn’t there but someone named Jimmy is. “Jimmy,” says Billy.” Hey, how you doin’? Got a question for you. You guys looking for a left-handed reliever?”

He raises his fist again. Yes! He tells Jimmy about Venafro. “I can make it real quick for you,” he says. He knows he wants to trade Venafro, but he doesn’t know who he wants in return.

How quick?

“Fifteen minutes?”

Fine.

“I can give you names in fifteen minutes,” says Billy. “Yeah, look I’d do this if I were you. And I’m not shitting you here, Jimmy. I’m being honest with you.”

Paul sees what is happening and walks out the door before Billy is finished. “I gotta find some more prospects,” he says. He needs to find who they want from the Mets in exchange for Venafro.

Billy hangs up. “Paul! We got fifteen minutes to get names.” He finds Paul already in his office flipping through various handbooks that list all players owned by the Mets. He takes the seat across from him and grabs one of the books and together they rifle through the entire Mets farm system, stat by stat. It’s a new game: maximize what you get from the Mets farm system inside of fifteen minutes. They’re like a pair of shoppers who have been allowed into Costco before the official opening time and told that anything they can cart out the door in the next fifteen minutes they can have for free. The A’s president, Mike Crowley, walks by and laughs. “What’s the rush?” he says. “We don’t need Rincon until the sixth or seventh inning.”

“What about Bennett?” asks Paul.

“How old is he?” asks Billy.

“Twenty-six.”

“Fuck, he’s twenty-six and in Double-A. Forget it.”

Billy stops at a name and laughs. “Virgil Chevalier? Who is that?”

“How about Eckert?” says Paul. “But he’s twenty-five.”

“How about this guy?” says Billy, and laughs. “Just for his name alone. Furbush!”

Anyone older than about twenty-three who is desirable will be too obviously desirable for the Mets to give up. They’re looking for a player whose promise they have a better view of than the Mets. Someone very young. It will be someone they do not know, and have never seen, and have researched for thirty seconds.

“How about Garcia?” Paul finally asks.

“What’s Garcia? Twenty-two?”

“Twenty-two,” says Paul.

He shows Billy the stats for Garcia and Billy says, “Garcia’s good. I’ll ask for Garcia.” He gets up and walks back to his office. “Fuck!” he says, on the way. “I know what I’ll do. Why don’t we go back to them and say, ‘Give us cash too!’ What’s the difference between Rincon and Venafro?”

Paul punches numbers into his calculator: 232,923.

“I’ll ask him for two hundred and thirty-three grand plus the prospect,” says Billy. “The money doesn’t mean anything to the Mets.”

Being poor means treating rich teams as petty cash dispensers: $233,000 is the difference between Venafro and Rincon’s salaries for the rest of the season. If he can get the Mets to give him the $233,000, he doesn’t even need to call his owner. He can just make the deal himself.

He pauses before he picks up the phone. “Should I call Sabean first?” He’s asking himself; the answer, also provided by himself, is no. As Billy calls Steve Phillips, Paul reappears. “Billy,” he says “you might also ask for Duncan. What can they say? He’s hitting .217.”

“Who would we rather have, Garcia or Duncan?” asks Billy.

The Mets’ secretary answers before Paul. Billy leans back and smiles. “Denise,” he says, “Billy Beane. Vice President and General Manager of the Oakland Athletics. Denise, who is the coolest GM in the game?” Pause. “Right again, Denise.” Denise’s laughter reaches the far end of Billy’s office. “Billy has the gift of making people like him,” said the man who had made Billy a general manager, Sandy Alderson. “It’s a dangerous gift to have.”

This time Steve Phillips is present, and ready to talk. “Look, I’m not going to ask you for a lot,” says Billy generously, as if the whole thing had been Phillips’s idea. “I need a player and two hundred and thirty-three grand. I’m not going to ask you for anyone really good. I have a couple of names I want to run by you. Garcia the second baseman and Duncan the outfielder who hit .217 last year.”

Phillips, like every other GM who has just received a call from Billy Beane, assumes there must be some angle he isn’t seeing. He asks why Billy sent Venafro down to Triple-A. He’s worried about Venafro’s health. He wonders why Billy is now asking for money, too.

“Venafro’s fine, Steve,” says Billy. He’s back to selling used cars. “This is just a situation for us. I need the money for…something else I want to do later.”

Phillips says he still wonders what’s up with Venafro. The last few times he’s pitched, he has been hammered. Billy sighs: it’s harder turning Mike Venafro into a New York Met than he supposed. “Steve, me and you both know that you don’t judge a pitcher by the last nine innings he threw. Art misused him. You should use him for a whole inning. He’s good against righties too!”

For whatever reason the fish refuses the bait. At that moment Billy realizes: the Mets are hemming and hawing about Venafro because they think they are going to get Rincon. “Look,” says Billy. “Here’s the deal, Steve.” He’s no longer selling used cars. He’s organizing a high school fire drill, and tolerating no cutups. “I’m going to get Rincon. It’s a done deal. Yeah. It’s done. The Giants want Venafro. I’ve told them they can have him for a player: Luke Robertson.”

“Anderson,” whispers Paul.

“Luke Anderson,” says Billy, easing off. “We like Anderson. We think he’s going to be in the big leagues. But I’d like to deal with you because Sabes doesn’t have any money. You can win this because you can give me two hundred thirty-three grand in cash, and he can’t. I don’t have to have the two hundred thirty-three grand in cash. But it makes enough of a difference to me that I’ll work with you.” He’s ceased to be the fire drill instructor and become the personal trainer. You can do it, Steve! You can win!

Whatever place he’s reached in the conversation, he likes. “Yeah,” he says. “It doesn’t have to be Garcia or Duncan. I’ll find a player with you. If it makes you feel better.” (I want you, and only you, to have Venafro.) “Okay, Steve. Whoever calls me back first gets Venafro.” (But if you drag your heels you’ll regret it for the rest of your life.)

Billy’s assistant tells him that Peter Gammons, the ESPN reporter, is on the line. In the hours leading up to the trade deadline Billy refuses to take calls from several newspaper reporters. One will get through to him by accident and he’ll make her regret that she did. Most reporters, in Billy’s experience, are simply trying to be the first to find out something they’ll all learn anyway before their deadlines. “They all want scoops,” he complains. “There are no scoops. Whatever we do will be in every paper tomorrow. There’s no such thing as a paper that comes out in an hour.”

It’s different when Peter Gammons calls. The difference between Gammons and the other reporters is that Gammons might actually tell him something he doesn’t know. “Let’s get some info,” he says, and picks up the phone. Gammons asks about Rincon and Billy says, casually, “Yeah, I’m just finishing up Rincon,” as if it’s a done deal, which clearly it is not. He knows Gammons will tell others what he tells him. Then the quid pro quo: Gammons tells Billy that the Montreal Expos have decided to trade their slugging outfielder, Cliff Floyd, to the Boston Red Sox. Billy quickly promises Gammons that he’ll be the first to know whatever he does, then hangs up the phone and says, “Shit.”

Cliff Floyd was the other player Billy was trying to get. “There’s more than one season,” Billy often said. What he really meant was that, in the course of a single season, there was more than one team called the Oakland Athletics. There was, for a start, the team that had opened the season and that, on May 23, he’d booted out of town. Three eighths of his starting lineup, and a passel of pitchers. Players who just a couple of months earlier he’d sworn by he dumped, without so much as a wave good-bye. Jeremy Giambi, for instance. Back in April, Jeremy had been Exhibit A in Billy Beane’s lecture on The New and Better Way to Think About Building a Baseball Team. Jeremy proved Billy’s point that a chubby, slow unknown could be the league’s best leadoff hitter. All Billy would now say about Jeremy is that walking over to the Coliseum to tell him he was fired was “like shooting Old Yeller.”

There was a less sentimental story about Old Yeller, but it never got told. In mid-May, as the Oakland A’s were being swept in Toronto by the Blue Jays, Billy’s behavior became erratic. Driving home at night he’d miss his exit and wind up ten miles down the road before he’d realize what had happened. He’d phone Paul DePodesta all hours of the night and say, “Don’t think I’m going to put up with this shit. Don’t think I won’t do something.” When the team arrived back in Oakland, he detected what he felt was an overly upbeat tone in the clubhouse. He told the team’s coaches, “Losing shouldn’t be fun. It’s not fun for me. If I’m going to be miserable, you’re going to be miserable.”

Just before the Toronto series the team had been in Boston, where Jeremy Giambi had made the mistake of being spotted by a newspaper reporter at a strip club. Jeremy, it should be said, already had a bit of a reputation. Before spring training he’d been caught with marijuana by the Las Vegas Police. Reports from coaches trickled in that Jeremy drank too much on team flights. When the reports from Boston reached Billy Beane, Jeremy ceased to be an on-base machine and efficient offensive weapon. He became a twenty-seven-year-old professional baseball player having too much fun on a losing team. In a silent rage, Billy called around the league to see who would take Jeremy off his hands. He didn’t care what he got in return. Actually, that wasn’t quite true: what he needed in return was something to tell the press. “We traded Jeremy for X because we think X will give us help on defense,” or some such nonsense. The Phillies offered John Mabry. Billy hardly knew who Mabry was.

On the way to tell Jeremy Giambi that he was fired, Billy tried to sell what he was doing to Paul DePodesta. “This is the worst baseball decision I’ve ever made,” he said, “but it’s the best decision I’ve made as a GM.” Paul knew it was crap, and said so. All the way to the clubhouse he tried to talk Billy down from his pique. He tried to explain to his boss how irrational he’d become. He wasn’t thinking objectively. He was just looking for someone on whom to vent his anger.

Billy refused to listen. After he’d done the deal, he told reporters that he traded Jeremy Giambi because he was “concerned he was too one-dimensional” and that John Mabry would supply help on defense. He then leaned on Art Howe to keep Mabry out of the lineup. And Art, occasionally, ignored him. And Mabry proceeded to swat home runs and game-winning hits at a rate he had never before swatted them in his entire professional career. And the Oakland A’s began to win. When Billy traded Jeremy Giambi, the A’s were 20–25; they had lost 14 of their previous 17 games. Two months later, they were 60–46. Everyone now said what a genius Billy Beane was to have seen the talent hidden inside John Mabry. Shooting Old Yeller had paid off.

Neither his trading of Jeremy Giambi nor the other moves he had made had the flavor of a careful lab experiment. It felt more as if the scientist, infuriated that the results of his careful experiment weren’t coming out as they were meant to, waded into his lab and began busting test tubes. Which made what happened now even more astonishing: as Billy Beane sat in his office in July, just a few months after he’d chucked out three eighths of the starting lineup, he insisted that the shake-up hadn’t been the least bit necessary. Between phone calls to other general managers he explained how the purge he’d conducted back in May, in which he’d ditched players left and right, “probably had no effect. We were 21–26 at the time. That’s a small sample size. We’d have been fine if I’d done nothing.” The most he will admit is that perhaps his actions had some “placebo effect.” And the most astonishing thing of all is that he almost believes it.

Two months later, he still didn’t want to talk about Jeremy Giambi. All that mattered was that the Oakland A’s were winning again. But they were still in third place in the absurdly strong American League West, and Billy worried that this year good might not be good enough. “We can win ninety games and have a nice little season,” he said. “But sometimes you have to say ‘fuck it’ and swing for the fences.”

And so he flailed about, seemingly at random, calling GMs and proposing this deal or that, trying to make a Fucking A trade. “Trawling” is what he called this activity. His constant chatter was a way of keeping tabs on the body of information critical to his trading success: the value the other GMs were assigning to individual players. Trading players wasn’t any different from trading stocks and bonds. A trader with better information could make a killing, and Billy was fairly certain he had better information. He certainly had different information. In a short two months with the Oakland A’s, for instance, Carlos Pena had transformed himself from a player Billy Beane coveted more than any other minor leaguer into a player everyone valued more highly than Billy did. He knew—or thought he knew—that Carlos was overvalued. The only question was: how much could he get for him?

Dangling Carlos from a hook, Billy tried to lure the Pittsburgh Pirates into giving him their slugging outfielder Brian Giles. When the Pirates resisted, he offered to send Carlos and his fourth outfielder Adam Piatt to Boston for outfielder Trot Nixon, and then send Trot Nixon and the A’s flame-throwing Triple-A reliever, Franklyn German, to Pittsburgh for Giles. Again, no luck. He then gave up on Giles and tried and failed to talk Cleveland’s GM, Shapiro, into sending him both his ace, Bartolo Colon, and his best hitter, Jim Thome, for Cory Lidle and Carlos Pena.

In all of this Billy Beane was bound to fail a lot more than he succeeded: but he didn’t mind! The failure wasn’t public; the success it led to was. Trawling in late June, using Carlos Pena as chum, he stumbled upon a new willingness of the Detroit Tigers to trade their young but expensive ace, Jeff Weaver. Billy didn’t have much interest in Jeff Weaver (at $2.4 million a year, pricey) but he knew that the Yankees would, and he had long coveted the Yankees’ only young, cheap, starting pitcher, Ted Lilly (as good as Weaver, in Billy’s view, and a bargain at $237,000). He sent Carlos Pena to Detroit for Weaver, then passed Weaver to New York for Lilly plus a pair of the Yankees’ hottest prospects. Somehow, in the bargain, he also extracted from Detroit $600,000. When Yankees GM Brian Cashman asked him how on earth he’d done that, Billy told him that it was “my brokerage fee.”

That had happened on July 5. He wasn’t finished; really he was just getting started. He made a run at Tampa Bay’s center fielder Randy Winn and while Tampa Bay’s management was willing to talk to Billy, they were too frightened of him to deal with him. One former Tampa executive says that “after the way Billy took [starting pitcher Cory] Lidle from them, they’ll never deal with him again. He terrifies them.” He came close to getting Kansas City outfielder Raul Ibanez, but then Ibanez went on a hitting tear that led Kansas City to reevaluate his merits and decide that Billy Beane was about to pick their pockets again. (The year before, at the trade deadline, Billy had given Kansas City nothing terribly useful for Jermaine Dye, just as, the year before, he’d given them next to nothing for Johnny Damon.)

With Carlos Pena gone, Billy re-baited his hook with Cory Lidle. Lidle had pitched poorly during the first half of the season but he was starting to look better. When Lidle went out to pitch, Billy rooted for him as he never had before—not simply for Lidle to win but for Lidle’s stock to rise. Kenny Williams, GM of the Chicago White Sox, expressed an interest in Lidle. Billy suggested a package that would yield, in return, the White Sox’s slugging outfielder Magglio Ordonez. The White Sox declined, but that conversation led to another, in which Billy discovered that the White Sox were willing to part with their All-Star second baseman and leadoff hitter, Ray Durham. To get Durham and the cash to pay the rest of Durham’s 2002 salary, all Billy had to give up was one flame-throwing Triple-A pitcher named Jon Adkins. Over the past eighteen months Billy had traded every pitcher in the A’s farm system whose fastball exceeded 95 miles per hour—except Adkins.

Ray Durham, acquired on July 15, had been a Fucking A trade. (It quickly inspired an article on baseballprospectus.com, the leading sabermetric Web site, with the title: “Kenny Williams, A’s Fan.”) In getting Durham, Billy got a lot more than just half of a season from a very fine player. Durham would be declared a Type A free agent at the end of the season. Lose a Type A free agent and you received a first-round draft pick plus a compensation pick at the end of the first round. If Kenny Williams valued those draft picks properly, he would have kept Durham on until the end of the season, and then let him walk. Those two draft picks alone were worth paying Ray Durham to play half a season; they were certainly worth more than the minor league pitcher the White Sox acquired for Durham.

This trading strategy came with a new risk, however. Baseball owners and players were, by the end of July, at work hammering out a new labor agreement. The players were threatening to strike; the owners were threatening to let them. The Blue Ribbon Panel Report had put oomph behind a movement, led by Milwaukee Brewer owner and baseball commissioner Bud Selig, to constrain players’ salaries and share revenues among teams. One of Selig’s proposals—tentatively agreed to by the players’ union—was to eliminate compensation for free agents. No more draft picks. Billy Beane was making a bet: it wouldn’t happen. The only way a new labor agreement occurs, he assumed, is if the players agree to some form of constraint on market forces, either through teams sharing revenues or some form of salary cap. And if they agree to that, the owners will be so relieved that they give the players what they want on every smaller issue.* “This is a small issue in the big picture,” he says. “The history of the union negotiations tells you that they’re never going to acquiesce to the slightest detail. If the owners do get revenue sharing, it’s going to be, ‘Grab your ankles.’ It’s going to be, ‘Do what you want with me. Beat me like a farm animal.’”†

Whereupon he bent over to illustrate what the owner of a baseball team might look like, were he to play the farm animal.

Cliff Floyd was Ray Durham all over again. Floyd would be a free agent at the end of the season and so, like Durham, a ticket for two more first-round draft picks. The trouble with Floyd, from the point of view of an impoverished team looking to acquire him, was that he was the only big star still left on the market. “His value will only fall so far,” says Billy.

In the time he spent trying to nail down Rincon, he had lost Floyd. Or so it seemed. Now he notices he has a voice mail message. While he was talking to Gammons, someone else called. He’s thinking it might be Sabean or Phillips calling to take Venafro’s 270 grand paycheck off his hands. Money is what he needs, and he hits his telephone keypad as if there’s money inside. There isn’t. “Billy,” says the soft, pleasant, recorded voice. “It’s Omar Minaya. Call me back, okay?” Omar Minaya is the Montreal Expos’ GM. Omar Minaya controls the fate of Cliff Floyd.

Billy puts his head in his hands and says, “Let me think.” Which he does for about ten seconds, then calls Omar Minaya. He listens as Minaya tells him what he already knows from Peter Gammons; that his offer for Cliff Floyd is nowhere close to the Red Sox offer. In exchange for one of the best left-handed hitters in the game, Billy Beane had offered a Double-A pitcher who was promising but hardly a prized possession. The Red Sox, amazingly, have agreed to cover the $2 million or so left on Cliff Floyd’s contract, and offered a smorgasbord of major and minor league players for Montreal to choose from—among them Red Sox pitcher Rolando Arrojo and a South Korean pitcher named Seung-jun Song. Plus, according to Cliff Floyd’s agent, it is suddenly Cliff Floyd’s dream to play for the Boston Red Sox (the Red Sox are likely to pay him even more than he is worth at the end of the year, when he becomes a free agent) and his distinct wish not to play for the Oakland A’s (who will bill Cliff Floyd for the sodas he drinks in the clubhouse). Floyd has a clause in his contract that allows him to veto a trade to Oakland.

Billy listens to the many compelling reasons why Omar is about to trade Cliff Floyd to the Red Sox, and then says, in the polite tones of a man trying to hide his discovery of another’s idiocy, “You really want to do that, Omar?”

Omar says he does.

“I mean, Omar, you really like those guys you’re getting from Boston?”

Omar, a bit less certainly, says that he likes the guys he’s getting from Boston.

“You like Arrojo that much, huh?” He speaks Arrojo’s name with a question mark after it. Arrojo? The Toronto Blue Jays’ GM, J. P. Ricciardi, said that watching Billy do a deal was “like watching the Wolf talk to Little Red Riding Hood.”

It takes a full twenty seconds for Omar to apologize for his interest in Rolando Arrojo.

“So who is this other guy?” says Billy “This Korean pitcher. How do you say his name? Song Song?”

Omar knows how to say his name.

“Well, okay,” says Billy. Yet another shift in tone. He’s now an innocent, well-meaning passerby who has stopped to offer a bit of roadside assistance. “If you’re going to send Floyd to Boston,” he says, “why don’t you send him through me?”

And Billy Beane now attempts to do what he has done so many times in the past: insert himself in the middle of a deal that is none of his business.

“Omar,” he says. “You’re in the catbird seat here. All you need to do is let the market come to you.”

He then explains: Omar can have the Red Sox’s money and he can have the Red Sox’s players plus another player from the Oakland A’s minor league system. Just about any player he wants, within reason. All he has to do is agree to give Cliff Floyd to Billy Beane for a few minutes, and let Billy negotiate with the Red Sox. He is explaining, without putting too fine a point on it, that Omar is not getting all he could get out of the Red Sox for Cliff Floyd.

The Red Sox were in their usual undignified pant to make the play-offs. They had twisted themselves into a position in their own minds where they could not not get Cliff Floyd. They were among the many foolish teams that thought all their questions could be answered by a single player. Cliff Floyd was the answer. Cliff Floyd was a guy the Boston newspapers would praise them for acquiring. Cliff Floyd would bring false hope to Fenway Park. Cliff Floyd, in short, was a guy for whom the Red Sox simply had to overpay. And if Omar Minaya hasn’t the stomach to extract every last hunk of flesh the Boston Red Sox are willing to part with in exchange for Floyd, Billy will do it for him. And once he’s done it, he will give Omar the players he was going to get anyway plus a minor leaguer from the Oakland farm system.

Billy Beane never had the first hope of landing Cliff Floyd. For Cliff Floyd to become an Oakland A, the Montreal Expos would have had to agree to pay the rest of Floyd’s 2002 salary. The Expos were now officially a failed enterprise, owned and operated by Major League Baseball. By Bud Selig. There is not the slightest chance that Bud Selig would pay a star to play for a team fighting for a spot in the play-offs. Billy had to have known that; what he’d been doing, all along, was making a place for himself in the conversation about Cliff Floyd. Everyone else in that conversation had money. All he had was chutzpah.

Omar’s now curious. He wants to know exactly how this new deal would work. Billy spells it out: you give me Floyd and I will deliver to you Arrojo and Song Song—or whatever his name is—plus someone else. Some other minor leaguer from the Oakland A’s system.

Omar still doesn’t quite follow: how will he do that? Billy explains that he will use Floyd to get Arrojo and Song Song and some other things too, from the Boston Red Sox. It goes without saying that he will keep those other things.

Omar now follows. He says it sounds messy

“Okay, Omar,” says Billy. “Let’s do this. Here’s what you do. Call them back and tell them that you want one other player, in addition to Arrojo and Song Song. His name is Youkilis.”

Euclis.

The Greek god of walks.

Youkilis, an eighth-round draft choice the previous year. Youkilis, the first college player turned up by Paul DePodesta’s computer, and ignored by the Oakland A’s scouting department. Youkilis, a man who but for the last residue of old baseball wisdom in Billy’s scouting department would have been taken by the Oakland A’s in the third round of the 2001 draft. Youkilis was the Jeremy Brown of the 2001 draft. He was tearing up Double-A ball, and was on the fast track to the big leagues. He played as if he was trying to break the world record for walking, and for wearing out the arms of opposing pitchers.

From the moment he started to talk to Omar Minaya about Cliff Floyd, Billy Beane was after Youkilis.

Omar has no idea who Youkilis is. “Kevin Youkilis,” says Billy, as if that helps. “Omar, he’s nobody. He’s just a fat Double-A third baseman.” A fat Double-A third baseman who is the Greek god of walks. Who just happened to have walked into some power last year. Yes: the Greek god of walks was now hitting a few more home runs. Which is, of course, the true destiny of the Greek god of walks.

Omar doesn’t understand how he can get Youkilis from the Red Sox, who have said they’ve made their best offer. “No, Omar,” says Billy. “Here’s how you do it. If I walk you through this, Omar, you can take it to the freaking bank. Trust me on this, Omar. He [Floyd’s agent] wants him in Boston. You know why? Boston can pay him. You don’t ask them for Youkilis. You just tell them Youkilis is in the deal. You just call them and tell them that without Youkilis they don’t have a deal. Then hang up. I guarantee you they’ll call you right back and give you Youkilis. Who is Youkilis?”

He speaks the name as he has never before, as if he can summon only contempt for anyone with an interest in this Youkilis. “Youkilis for Cliff Floyd?” he says “It’s ridiculous. Of course they’ll do it. Fucking Larry Lucchino [the Red Sox president] doesn’t know who the fuck Youkilis is. How are they going to explain to people that they didn’t get Cliff Floyd because they wouldn’t give up Youkilis?”

Poor teams enjoy one advantage over rich teams: immunity from public ridicule. Billy may not care for the Oakland press but it is really very tame next to the Boston press, and it certainly has no effect on his behavior, other than to infuriate him once a week or so. Oakland A’s fans, too, were apathetic compared to the maniacs in Fenway Park and Yankee Stadium. He could safely ignore their howls.

Omar doesn’t buy it. He thinks maybe Billy Beane is screwing up his deal.

“Omar, all I’m trying to do is give you a free player from me. And if they don’t do it, what have you lost? You can still do the deal.”

Omar says he’s worried about losing his deal. He’s got Bud Selig sitting on his shoulder. Omar, thanks to Bud Selig, is in violation of Billy Beane’s Trading Rule #2: “The day you say you have to do something, you’re screwed. Because you are going to make a bad deal.”

“Omar,” Billy says, “if they think they are going to get Floyd, Kevin Youkilis is not going to get in the way.” Billy Beane helps Omar to imagine the Boston headlines. NEW RED SOX OWNERS LOSE PENNANT TO KEEP FAT MINOR LEAGUER.

Now Omar understands; now Omar very nearly believes. But Omar is also curious: who is this Youkilis fellow that has Billy Beane so worked up? Perhaps Youkilis is someone who should be not an Oakland A, but a Montreal Expo.

“Youkilis?” says Billy, as if he’s only just heard of the guy and very nearly forgot his name. “Just a fat kid in Double-A. Look at your reports. He’s a ‘no’ for you. He’s a ‘maybe’ for me. From our standpoint he’s just a guy we like because he gets on base.”

(Silly us!)

Now Omar wants to make it more complicated than it is.

“Omar, Omar,” says Billy, “the point is I think you can get him in the deal and if you do I’m getting you something for nothing.”

He puts down the phone. “He’ll call Boston but I don’t think he’s going to push them,” he says.

A’s president Mike Crowley pokes his head into Billy’s office. “Steve’s on the phone.” Steve in this case is Steve Schott, A’s owner.

Billy’s thoughts linger on Youkilis. He imagines, fairly accurately as it turns out, the next words he’ll hear from the Red Sox. They’ll know of course that it was he, and not Omar, who has dropped the stink bomb of Youkilis. They’ll know because he, and no one else, has tried to get Youkilis from them in the past. They’ll know, also, because the Red Sox assistant GM, Theo Epstein, talks to Billy Beane as often as he can. Epstein is a twenty-eight-year-old Yale graduate who has known for some time that he’d like to be the general manager of a big league team and, when he is, which general manager he’d most like to be. The Boston Red Sox are moments away from joining Billy Beane in his crusade to emancipate fat guys who don’t make outs. All this Billy knows, and he still thinks Boston will give up Youkilis. What he doesn’t know is that Theo Epstein has new powers—new Red Sox owner John Henry listens to everything he says—and has used them to establish Kevin Youkilis as the poster child for the Boston Red Sox farm system. (“Three months earlier,” Epstein will later say, “and Billy would have had him.”)

“Billy, Steve’s still waiting to talk!” Mike Crowley again. His owner again. Billy looks around as if he’s forgotten something; he’s spent too much time on Youkilis. He needs to raise some cash. He goes back to his phone and calls Steve Phillips, the Mets GM, one last time. “Steve. Here’s the deal. I don’t want Rincon pitching against me tonight.” He listens for a bit, and hears nothing that makes him happy. When he hangs up, he says, “He has no money. He needs what he has to sign Kazmir.” (Kazmir is the high school pitcher—now the high school pitching holdout—drafted by the Mets nearly two months earlier.)

The Mets have no money to waste. This is new, too. The market for baseball players, like the market for stocks and bonds, is always changing. To trade it well you needed to be adaptable.

Every minute that passes is a minute Brian Sabean—or even Steve Phillips!—has to talk Mark Shapiro into backing out of the two-hour promise he’s made Billy. Billy hollers to Mike Crowley: “Tell Schott that if we don’t move Venafro, I’ll sell Rincon for twice the price next year. No. Tell him that I’ll make him a deal. If I don’t do it, I’ll cover it. But I keep anything over twice the savings.”

Mike Crowley doesn’t know what to do with this. His GM, who earns 400 grand a year, is telling his owner that he’ll take an equity stake in a single player. Go down this road and Billy Beane could make himself a very rich man, simply by dealing players as well as he has done. No reply comes back from the owner, and Billy assumes he is free to do what he wants with Rincon. (Later, and after the fact, the owners will indeed give him authority to do the deal.) He gives the Mets and Giants fifteen minutes more. Finally, he decides. He’ll take the risk. He picks up the phone to call Mark Shapiro to acquire Rincon.

Phone in hand, almost casually, Billy says to Paul DePodesta, now seated on Billy’s sofa, “Do you want to go down and release Magnante?”

“Do I want to?” says Paul. He looks right, then left, as if Billy must be talking to some other person, someone who enjoys telling a thirty-seven-year-old relief pitcher that he’s washed up. When he looks left he can see the Coliseum a few yards away, through Billy’s office window. It wasn’t that Mags was just four days short of his ten-year goal. He’d get his pension. It was that, in all likelihood, Mags was finished in the big leagues.

“Someone’s got to talk to him,” says Billy. Now, suddenly, there is a difference between trading stocks and bonds and trading human beings. There’s a discomfort. Billy never lets it affect what he does. He is able to think of players as pieces in a board game. That’s why he trades them so well.

“Call Art,” says Paul. “That’s his job.”

Billy starts to call Art and then remembers that he hasn’t actually made the trade, and so reverses himself and calls Mark Shapiro in Cleveland. It’s 6:30 P.M. The game against the Indians starts in thirty-five minutes.

“Mike Magnante has just thrown his last pitch in the big leagues,” says Paul.

“Sorry I took so long, Mark,” says Billy.

No problem, But since you did, do you want to wait until after the game to take Rincon?

“No, we want him now. We want to get him in our dugout tonight.”

Why the rush?

“By and large Magnante cost us the game last night and Rincon won the game.”

Okay. No big deal. We’ll do it now.

“You feel comfortable with Ricardo’s health, right?”

Right.

“We’re going to have to release a guy before the game,” says Billy. “In the spirit of speeding things up, you wanna call Joel?” Joel is Joel Skinner, the Indians manager. Panic rises on Billy’s face. “Oh shit,” he says. “McDougal. He has a little tweak in his leg. You know about that, right?” McDougal’s the player Billy’s giving up. McDougal’s also been dogging it during workouts. He’s conveyed to the A’s minor league coaching staff a certain lack of commitment to the game. But these things the Cleveland Indians are required to learn the hard way.

No problem. I know about the tweak.

Billy hangs up and dials Art Howe’s number. The A’s manager has just returned to his office beside the clubhouse.

“Art. It’s Billy. I have some good news and some bad news.”

Art gives a little nervous chuckle. “Okay.”

“The good news is you’ve got Rincon.”

“Do I?”

“The bad news is you gotta release Magnante.”

Silence on the other end of the line. “Okay,” Art finally says.

“And you’ve got to do it before the game.”

“Okay.”

“I know it’s not the best way to get rid of a guy but we got a good pitcher.”

“Okay.”

Billy hangs up and turns to Paul, “Can we designate Magnante for assignment?” This is a prettier way to release a player because it leaves open the possibility that some other club will claim him, and take his salary off Oakland’s hands. When you designate a guy for assignment, Billy explains, “you put him in baseball purgatory. But he can’t pray his way out.”

He then makes several quick calls. He calls the A’s equipment manager, Steve Vucinich. “Voos. We gotta get rid of Mags by game time. Yeah. You have twenty-five minutes to get him out of there.” He calls the Mets’ Steve Phillips. “Steve, I got the guy I wanted. Rincon.” (For you, it’s Venafro or nothing.) He calls the Giants’ Brian Sabean. “Brian. Hey, Brian. Hey, it’s Billy. I’ve made a deal for Rincon right now.” (So don’t think you can wait me out.) He calls Peter Gammons and tells him what he’s done, and that he’s not doing anything else.

Then he brings in the Oakland A’s public relations man, Jim Young, who agrees he should have a press release ready before the game. He also says Billy should make himself available to the media. “Do I have to go talk to them?” Billy asks. He’s already talked to everyone he wants to talk to.

“Yes.”

After the final call, his phone rings. He looks at his caller ID and sees it’s from the visitors’ clubhouse. He picks it up.

“Oh, hi Ricardo.” It’s Ricardo Rincon, who is Mexican, and normally gives his interviews through an interpreter.

“Ricardo, I know it’s a little bit shocking for you,” says Billy. His syntax changes slightly, he’s groping for a Mexican mode of expression and winds up saying whatever he can think of that Ricardo might understand. “But we have been trying to get you for a long time. You’re going to love the guys on the team. They’re fun.”

Ricardo is trying to get it clear in his head that he’s supposed to do what he’s just been asked to do, take off his Cleveland Indians uniform, gather his personal belongings, and walk down the hall into the Oakland clubhouse and put on an Oakland uniform. He can’t quite get his mind around it.

“Yes! Yes!” says Billy. “I don’t know if you’ll pitch tonight. But you’re on our team tonight.”

Whatever Ricardo says he means: Oh my God, I might actually have to pitch tonight?

“Yes. Yes. Possibly you’ll punch out Jim Thome!” Possibly you will punch out Jim Thome. Billy is becoming, quickly, a Mexican immigrant.

“We’ll have a uniform and everything ready for you.” And everything. He’s had just about enough touchy-feely for one evening. He tries to lead the conversation to a not horribly unnatural conclusion. “Where are you from, Ricardo?”

Ricardo says he’s from Veracruz, Mexico.

“Well, Veracruz is closer to here than to Cleveland. You’re closer to home!”

He finishes that one, hangs up, and says, “It’s gotten to be a longer road trip for Ricardo than he expected.” He looks absolutely spent. The wad of tobacco is gone from his upper lip and his mouth is dry. He gargles with the glass of water on his desk, and spits. “I’ve got to work out,” he says.

At that moment Mike Magnante was removing his Oakland uniform and Ricardo Rincon was removing his Cleveland one. Mags quickly left the Oakland clubhouse; he’d come back for his things later when no one was around. His wife had brought the kids to the game so he couldn’t just leave. Magnante watched the game with his family until the sixth inning, and then left so he wouldn’t have to answer questions from the media. He had no desire to call further attention to his situation. In his youth he might have mouthed off. He would certainly have borne a grudge. But he was no longer young; the numbness had long since set in. He thought of himself the way the market thought of him, as an asset to be bought and sold. He’d long ago forgotten whatever it was he was meant to feel.

The main thing was that Mags was gone from the clubhouse before Billy walked across to change into his sweats. As Billy headed in, however, he bumped into Ricardo Rincon heading out, in street clothes. Ricardo remained confused. He had heard he was going to the San Francisco Giants, or maybe the Los Angeles Dodgers. He’d never imagined he might be an Oakland A. And he still doesn’t understand the full implications of what’s happened. The Oakland A’s only left-handed relief pitcher is going out to find a seat in the stands to watch the game. Billy leads him back into the clubhouse where the staff has just finished steaming RINCON onto the back of an Oakland A’s jersey. “You’re on our team now,” says Billy.

Ricardo Rincon walked back into his new clubhouse, put on his new uniform, and sat down and watched the entire game on television. “I was not ready,” he said. “I couldn’t concentrate.” His left arm, however, felt great.