Chapter Ten

ANATOMY OF AN UNDERVALUED PITCHER

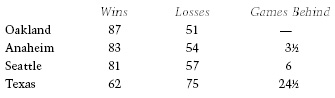

AFTER BILLY ACQUIRED Ricardo Rincon and Ray Durham, the team went from good to great. The only team in the past fifty years with a better second half record than the 2002 Oakland A’s was the 2001 Oakland A’s, and even they were just one game better. On the evening of September 4, the standings in the American League West were, with the exception of the Texas Rangers, an inversion of what they had been six weeks before.

The Anaheim Angels were the second hottest team in baseball. They’d won thirteen of their last nineteen games, and yet lost ground in the race. The reason for this was that the Oakland A’s had won all of their previous nineteen games—and tied the American League record for consecutive wins. On the night of September 4, 2002, before a crowd of 55,528, the largest ever to see an Oakland regular season game, they had set out to do what no other team had done in the 102-year history of the league: win their twentieth game in a row. By the top of the seventh inning, up 11–5 against the Kansas City Royals, with Tim Hudson still pitching, the game seemed all but over.

Then, suddenly, Hudson’s in trouble. After two quick outs he gives up one single to Mike Sweeney and another, harder hit, to Raul Ibanez. Art Howe emerges from the dugout and glances at the bullpen.

What turned up in the A’s bullpen seemed to vary from one night to the next. On this night the less important end of the bench held a cynical, short, lefty sidewinder Billy Beane had tried and failed to give away, Mike Venafro, and two guys newly arrived from Triple-A: Jeff Tam and Micah Bowie. On the more important end of the bench was a clubfooted screwball pitcher with knee problems; a short, squat Mexican left-hander who spoke so little English that he called everyone on the team “Poppy”; and a tempestuous flamethrower with uneven control of self and ball. Jim Mecir, Ricardo Rincon, Billy Koch. Of the entire bullpen, in the view of the Oakland A’s front office, the most critical to the team’s success was a mild-mannered Baptist whose delivery resembled no other pitcher in the major leagues: Chad Bradford. Billy has instructed Art Howe to bring in Bradford whenever the game is on the line. In most cases when Bradford came out of the pen, the game was tight and runners were on base. Tonight, the game isn’t tight; tonight, history is calling Chad Bradford in from the pen.

Art Howe pulls his right hand out of his jacket and flips his fingers underhanded, like a lawn bowler. Taking his cue, Bradford steps off the bullpen mound and walks toward the field of play. Before reaching it, he pulls the bill of his cap down over his face and fixes his eyes on the ground three feet in front of him. He’s six foot five but walks short. Really, it’s a kind of vanishing act: by the time he steps furtively over the foul line, he’s shed himself entirely of the interest of the crowd. If you didn’t know who he was or what he was doing you would say he wasn’t making an entrance but a getaway.

Baseball nourishes eccentricity and big league bullpens have seen their share of self-consciously colorful oddballs. Chad Bradford was the opposite. He didn’t brush his teeth between innings, like Turk Wendell, or throw temper tantrums on the mound, like Al Hrabosky. He didn’t stomp and glare and leap dramatically over the foul lines. His mother, back home in Mississippi, often complained about her son’s on-field demeanor. Specifically, she complained that he never did anything to let people know how handsome and charming he actually was. For instance, he never allowed the television cameras to see his winsome smile, even when he sat in the dugout after a successful outing. Chad never smiled because he was mortified by the idea of the TV cameras catching him smiling—or, for that matter, doing anything at all.

None of it helps his cause of remaining inconspicuous. Once he’s on the mound, nothing he does can wall him off from the crowd or the cameras. He makes his living on the baseball field’s only raised platform, and in such a way as to call to mind a circus act. Sooner or later he needs to throw his warm-up pitches, and, when he does, fans who have never seen him pitch gawk and point. In their trailers outside the stadium TV producers scramble to assemble the tape the announcers will need to explain this curiosity. Pitching out of the stretch, he does not rear up and back, like other relief pitchers. He jackknifes at the waist, like a jitterbug dancer lurching for his partner. His throwing hand swoops out toward the plate and down toward the earth. Less than an inch off the ground, way out where the dirt meets the infield grass, he rolls the ball off his fingertips. When subjected to slow-motion replay, as this motion often is, it looks less like pitching than feeding pigeons or shooting craps. The announcers often call him a sidearm pitcher, but that hasn’t been true of him for nearly four years. He’s now, in baseball lingo, a “submariner,” which is baseball’s way of making a guy who throws underhand sound manly.

The truth is that there is no good word to describe Chad Bradford’s pitching motion; “underhand” doesn’t capture the full flavor of it. This year, for the first time in his career, Chad Bradford’s knuckles have scraped the dirt as he throws. Once during warm-ups his hand bounced so violently off the ground that the baseball ricocheted over the startled head of Toronto Blue Jays’ outfielder Vernon Wells, minding his own business in the on-deck circle. ESPN had replayed that one, over and over. Chad’s new fear is that he’ll do it again, in a game, and that the television cameras will catch him at it, and everyone will be paying him attention all over again.

The odd thing about Chad Bradford is that he wants so badly to be normal. Normal is what he’s not. It’s not just that he throws funny. His idiosyncratic streak runs straight down to the bottom of his character. Back in high school he had this shiny white rock he sneaked out with him to the mound. He’d noticed it one day when he was pitching. He was pitching especially well that day and the rock didn’t look like any rock he’d ever seen on the mound. He attributed some part of his success to the presence of the shiny white rock. When he was done pitching, he picked up the rock and carried it home with him. For the next three years he never ventured to the pitcher’s mound without his rock. He’d sneak it out with him in his pocket and put it on the mound, just so, and in such a way that no one ever noticed.

By the time he reached the big leagues, he’d weaned himself of his lucky rock but not of the frame of mind that created it. He had the tenacious sanity of the slightly mad. A big league pitcher who wishes to avoid attention, Chad Bradford has learned to disguise his superstitions as routines. There are things he always does—like throwing exactly the same number of pitches in the bullpen, in exactly the same order; or like telling his wife to leave the stadium the moment he enters a game. There are things he never does—like touch the rosin bag.

His twin desires—to succeed, and to remain unnoticed—grow less compatible by the day. Chad Bradford’s 2002 statistics imply, to the A’s front office, that he is not just the best pitcher in their bullpen but one of the most effective relief pitchers in all of baseball. The Oakland A’s pay Chad Bradford $237,000 a year, but his performance justifies many multiples of that. At one point the Oakland A’s front office says that if Bradford simply continues doing what he’s done he’ll one day be looking at a multi-year deal at $3 million plus per. The wonder isn’t merely that they have him so cheaply, but that they have him at all. The wonder is that, until they snapped him up for next to nothing, nobody in the big leagues paid any attention at all to Chad Bradford.

In this respect, if no other, Chad Bradford resembled a lot of the Oakland A’s pitchers. The A’s had the best staff in the American League and yet of all their pitchers only Mark Mulder, one of the team’s three brilliant starters, had failed to inspire serious doubts at some point in his career in the baseball scouting mind. The team’s second ace, Tim Hudson, was a short right-handed pitcher who couldn’t get himself drafted at all in 1996, after his junior year in college, and then not until the sixth round of the 1997 draft. The team’s third ace, Barry Zito, had been spat upon by both the Texas Rangers, who took him in the third round of the 1998 draft but declined to pay him the $50,000 required to sign him, and the San Diego Padres, for whom Zito privately auditioned and badly wanted to play. The Padres told Zito that he didn’t throw hard enough to make it in the big leagues. The Oakland A’s disagreed and selected him with the ninth pick of the 1999 draft. Three years later a top executive for those same San Diego Padres would say that the reason the Oakland A’s win so many games with so little money is that “Billy got lucky with those pitchers.”

And he did. But if an explanation is where the mind comes to rest, the mind that stopped at “lucky” when it sought to explain the Oakland A’s recent pitching success bordered on narcoleptic. His reduced circumstances had forced Billy Beane to embrace a different mental model of the Big League Pitcher. In Billy Beane’s mind, pitchers were nothing like high-performance sports cars, or thoroughbred racehorses, or any other metaphor that implied a cool, inbuilt superiority. They were more like writers. Like writers, pitchers initiated action, and set the tone for their games. They had all sorts of ways of achieving their effects and they needed to be judged by those effects, rather than by their outward appearance, or their technique. To place a premium on velocity for its own sake was like placing a premium on a big vocabulary for its own sake. To say all pitchers should pitch like Nolan Ryan was as absurd as insisting that all writers should write like John Updike. Good pitchers were pitchers who got outs; how they did it was beside the point.

Pitchers were like writers in another way, too: their output was harder than it should have been to predict. A twenty-two-year-old phenom with superior command wakes up one morning in such a precarious mental state that he’s hurling pitches over the catcher’s head. Great prospects flame out, sleepers become stars. A thirty-year-old mediocrity develops a new pitch and becomes, overnight, an ace. There are pitchers whose major league statistics are much better than their minor league ones. How did that happen? It was an odd business, this getting of outs. Obviously a physical act, it was also, in part, an act of the imagination. In the minor leagues Tim Hudson develops a new pitch, a devastating change-up, that makes him look like a different pitcher from the one the A’s drafted in the sixth round. Between junior and real college, Barry Zito refines the delivery of his curveball to the point where it is indistinguishable, as it leaves his hand, from his otherwise uninteresting fastball. The adjustments that lead to pitching success are mental as much as they are physical acts.

Of all the odd out-getters on the Oakland A’s pitching staff, Chad Bradford is the least orthodox. He has made it to the big leagues less on the strength of his arm than on the quality of his imagination. No one sees that now; because no one really knows who he is, or cares. When you know just a bit about him, you can see what powerful tricks a pitcher’s imagination can play. But to do that you had to go back a ways, to before Chad Bradford became the man now making a spectacle of himself before 55,528 fans in Oakland’s Coliseum.

CHAD BRADFORD grew up the youngest child of a lower-middle-class family in a small town called Byram, Mississippi, outside of the larger one called Jackson. “Country” is how he describes himself. Not long before Chad’s second birthday his father suffered a stroke that nearly killed him, and left him paralyzed. The doctors had told his father that he’d never walk again. His father insisted that just wasn’t true. He looked up from his bed, stone-faced, and announced his intention to raise his three boys and earn a living. Through an act of will, which he also thought of as an act of God, he did just that. By Chad’s seventh birthday his father was able not only to walk but, in a fashion, to play catch with his son. He would never again be able to lift his arm over his shoulder, so he couldn’t throw properly. But he could get a glove up to stop a ball. And after he caught the ball from Chad, he would toss it back to him underhanded. The strange throwing motion stuck in the little boy’s mind.

Playing catch with his father was one of the things that made Chad happiest. His father didn’t have any particular ambition for him, except that he should be happy, remain a Christian, and that his happiness and his Christianity should occur within the confines of Mississippi. The Bradfords didn’t know any professional baseball players; they didn’t know anyone who knew any professional baseball players. But twice Chad was asked by his school-teachers to write autobiographical essays, and both times he took professional baseball as his theme. At the age of eight he wrote: What I Want to Be When I Grow Up.

If I were a A grown up

I would be a baseball player

And I would play for the Dodgers.

I hope to play for the Cardinals too.

I hope to play for the Oriole too

And for all the teams I would

Play shotestop.

“Shotestop” being the phonetic spelling, in Byram, Mississippi. Five years later, when Chad was thirteen, his teacher asked him and the other students to write the stories of their lives, as they looked back on them from their imagined old age. With the perspective of hindsight Chad Bradford could see that he had married right out of school, had two children, a son and a daughter, and become not a big league shortstop but a big league pitcher. He imagined no other future for himself and so it was lucky that no other future awaited him. Right after his high school graduation, at the age of eighteen, he married his girlfriend, Jenny Lack, who soon bore him a son, then a daughter. Between the two births, at the age of twenty-three, Chad Bradford made his debut in the major leagues with the Chicago White Sox. The power of an imagination can arise from what it refuses to foresee.

Between the eighth grade and the big leagues there was only one hitch: Chad wasn’t any good. His ambition was a fantasy. Just about every baseball player who makes it to the big leagues was all-everything in high school; just about every big league pitcher dominated high school hitters. As a fifteen-year-old high school sophomore Chad Bradford was lucky just to make the team. He didn’t play any sport other than baseball and didn’t exhibit any particular athletic ability. Central Hinds Academy in Byram, Mississippi, had graduated hundreds of baseball players more promising than Chad Bradford and none of them had ever played professionally. Anyone Chad told he planned to become a professional baseball pitcher looked at him with the same gawking awe as his presence on a big league mound would later elicit. As a consequence he stopped telling people.

One of the people he didn’t tell was his high school baseball coach, Bill “Moose” Perry. Chad, like everyone he knew, was raised Baptist. Moose wasn’t just his coach but also his minister. This curious blending of roles meant, in practice, that when Moose needed to slap sense into one of his players, he felt sure he did it with the hand of God. Moose looked at Chad Bradford, aged fifteen, and saw a player who needed slapping. To Moose, Chad Bradford was just a silly, lazy boy, who had come out for the baseball team not because he had any aptitude for, or interest in, the game but because he wanted to hang around with his friends who did. “The one thing Chad was, he was a good student,” said Moose, years later, looking for something nice to say. “And the way it was at that school, if they showed any ability in anything, you wanted to encourage them. But Chad’s promise was basically that he wanted to be there. That was it. It’s horrible to say, but it’s true.”

Chad told Moose that he wanted to pitch, but Moose couldn’t see how. “He might have been the type of guy who would pitch games that were meaningless,” said Moose, “but I wouldn’t have let him pitch any game that mattered. His curveball didn’t do anything but spin. He didn’t throw hard. His fastball, it was like setting it up there on a hittin’ tee.”

Moose had other jobs, aside from coaching and preaching to high school baseball players. One of them was chapel leader for the New York Mets’ Double-A team in Jackson, Mississippi. In that capacity, a few years earlier, he’d led Billy Beane in worship. (Billy, a lapsed Catholic, says he went to hedge his bets.) The season before Chad Bradford’s sophomore year, Moose preached to a sidearm pitcher from a visiting team. After the service Moose asked the pitcher how he got his effects, and the pitcher gave him a tutorial. One winter afternoon, before the season started, when the Central Hinds Academy baseball field was underwater and the team couldn’t practice properly, Moose took Chad aside on the football field and asked him to try out this stuff the minor leaguer had shown him. Chad dropped his arm down just above a straight sidearm, from twelve to two o’clock, and, sure enough, his fastball moved. He still couldn’t throw anything but a fastball, but now it tailed in on right-handed hitters and away from lefties. Chad could always throw the ball over the plate; now, thanks to his minister and coach, he could throw the ball over the plate in a way that hitters didn’t enjoy.

All of a sudden Moose had a pitcher he could use, at least in theory. In practice Chad was still, as Moose put it, “silly.” To make him less so, to toughen him up, Moose insisted that Chad cuss each time he threw a pitch. Anyone who wandered by Central Hinds Academy’s baseball field of an evening in the early 1990s would see a gangly, peach-fuzzed young man sidearming pitches at his preacher, with each pitch booming out: “Shit!”

Throwing sidearm didn’t come naturally to Chad. He’d leave practice every night and go home to the family’s warm little brick house and play catch with his father, who remained unable to lift his partially paralyzed right arm over his shoulder and so still pitched the ball back to him underhand. His father remembers when Chad came home with his new sidearm delivery—and new movement on his ball. “I couldn’t catch it!” he says. “It was whoosh. Whoosh. He like to have killed me. Right then I said, ‘Uh-oh, no more pitch and catch.’”

Chad turned his attention to the side of the house. The gap between the two holly bushes in front was about the width of home plate. He’d practice sidearming the ball against the brick without hitting the bushes. He broke a few windows. His father announced he would build Chad a pitcher’s mound. (“My dad can build anything.”) His father hooked a piece of chain-link fence to a four-by-four post, tacked a carpet on top, and drew a strike zone on the carpet. He walked off sixty feet six inches, and, out of the Mississippi mud, sculpted a pitcher’s mound. Every day after practice Chad threw off that mound. Years later, when he was in the minor leagues, he would come home to Byram, Mississippi, in the off-season, and throw off the mound his father had built for him.

The motion still wasn’t comfortable but the more he worked at it the better he felt, and when he saw the misery his new trick caused he decided not to worry about his own personal discomfort. “I’d see the hitters kind of backing out against me and I thought: ‘Hey, this is going to work.’” Still, he was never an all-star; no one imagined that he would amount to anything more than a good high school pitcher. Upon graduation, Chad was the only one who thought he might still play baseball. “I wasn’t recruited by any Division I schools,” he’d confess, and then laugh. “I wasn’t recruited by any Division II schools either.” He went over and talked to the coach at Hinds Community College, a few miles down the road. The coach there said he thought he might be able to use another pitcher, so there he went, pausing only long enough for Moose to perform his wedding ceremony.

At every level of baseball, including Little League, Chad Bradford might reasonably have decided that his baseball career was more trouble than it was worth. He couldn’t explain it, he just loved playing the game. “I wish I could answer the question of where that love for the game comes from,” he said, “but I don’t know.” He pitched well in junior college but never so well that anyone thought he had a future in the game. Or, rather, no one but Warren Hughes, a scout for the Chicago White Sox. Hughes was an odd duck, an Australian who had pitched for the Australian National team before landing a baseball scholarship at the University of South Alabama. When Hughes first saw Chad pitch, he’d only just started scouting for the White Sox, and he hadn’t yet been dissuaded from scouting players who didn’t fit professional baseball’s various molds. “You didn’t see many guys who threw from that angle who it looked natural to,” said Hughes. “It just kind of intrigued me that from that arm slot he had such great command.” It was a three-and-a-half-hour drive from Hughes’s home in Mobile, Alabama, to Hinds Community College, but Hughes made it often.

At first, Chad didn’t even know he was being scouted. He was shocked when, at the end of the 1994 season, he received a Western Union telegram from the Chicago White Sox, telling him that the team had drafted him in the thirty-fourth round. They didn’t plan to offer him a contract, the telegram said, but they controlled his rights for the next year. They planned to keep an eye on him. The next year Warren Hughes, who never actually said much to Chad, kept turning up at Chad’s games. “Pitchers that throw like that you have to see several times to appreciate,” Hughes explained. “The more I’d see Chad, the more I’d appreciate him.”

Hughes told Chad that the White Sox didn’t have the money to sign him in 1995, and that he should continue with his education. That year Chad went completely undrafted—no other big league team had even noticed him—and set off for the University of Southern Mississippi. There he continued to pitch, to a big league scouting audience of one. The American South was crawling with baseball scouts but none of them had the slightest interest in Chad Bradford. No other White Sox scout came to see Chad—just this quirky Australian. The following year, 1996, Warren Hughes carted up to Chicago videotapes he’d made of Chad pitching, with a view to persuading the White Sox to draft Chad. But before he bothered, he called Chad to make sure he was willing to sign.

“Chad,” he said. “How many other scouts have come to talk to you?”

“None.”

“Well, Chad,” he said. “It looks like I’m it. Looks like I’m your shot.”

He told Chad that if he would agree in advance to sign, the White Sox would again take him in a lower round but this time offer him $12,500 to sign. Even then Chad sensed that the White Sox didn’t take him seriously—that to them he was just a guy to fill out a minor league roster. The only evidence he had of their interest was this lone Australian fellow who for some reason kept turning up in rural Mississippi. He couldn’t decide what to do: finish college or become a White Sox minor league pitcher. He did what he now always did when he couldn’t decide what to do. He called Moose, and asked him what he should do.

“Chad,” Moose asked, more minister than coach. “How bad you want to play pro baseball?”

“It’s all I ever dreamed of.”

“Then you’re a fool not to take their money.”

He spent his first full season in the minor leagues in high A ball. It didn’t go well. In small-time college baseball his 86-mph fastball seemed respectable enough. Out here it looked faintly ridiculous. He had a wife and a son and couldn’t help but wonder if he’d made a mistake not finishing school. They’d run through the signing bonus. He was making a thousand dollars a month in the minor leagues. In the off-season he drove a forklift and swept out trailers. “I’m looking at my numbers in the off-season,” he said, “and I’m thinking: should I be doing this?” When he turned up in spring training for the 1998 season, the White Sox asked him the same question. The pitching coaches informed him that he’d been officially classified a “fringe prospect.” “They said, ‘If you have a good season, you can stay around. If not, you’re on your way out.’”

His goal at the start of the 1998 season was simply to keep his job. Late that spring several people noticed that he seemed to be approaching that job differently. He’d changed his delivery, so that he came at the hitter from a lower angle. In college he had drifted, unthinkingly, from two o clock to three o clock, from a three-quarters delivery to straight sidearm. That’s where he was at the end of his dismal first season in the minor leagues. Now, for the first time in his career, he found his point of release well below his waist. But until he watched tape of himself Chad had no idea that he’d changed anything at all. He never did: his development into a pitcher who looked like he belonged in a slow-pitch softball game was unconscious. Feeling himself falling, he had reached back blindly for something to grab hold of; the curious motion was the first stable object he found. “Moose took me from twelve to two,” he said. “But I honestly don’t know how I went down lower from there. I have no idea what happened. I can’t explain it.” All he knew was that when he threw it from lower down, his ball had a new movement to it that flummoxed hitters during minor league spring training, and continued to flummox them in Double-A ball.

In late June, the Chicago White Sox promoted Chad from Double-A to its Triple-A team in Calgary. When he arrived, he found out why: his new home field was high in the foothills of the Canadian Rockies, wind blowing out. The place was famously hellish on pitching careers: the guy he’d come to replace had simply quit and skipped town. The first game after Chad arrived, his team’s starter gave up six runs in the first two thirds of an inning. The first reliever came on and gave up another seven runs without getting an out. What should have been ordinary fly balls rocketed through the thin mountain air every which way out of the park. Still in the top of the first inning, and his team already down 13–0, the Calgary manager pointed to Chad. “When I see I’m next,” said Chad, “I’m thinking, ‘what the hell am I doing here?’” He went into the game and found the answer waiting for him. When he left the game two hours later, it was the top of the eighth and the score was 14–12. He’d gone six and a third innings and given up a single run. The pitcher who replaced him promptly gave up five more runs and the final score was 19–12.

An obscure, soft-tossing Double-A pitcher, who had never gone more than a couple of innings in a minor league game, had thrown six and a third merciless innings in maybe the toughest ballpark in Triple-A. As astonishing as the performance had been, the really curious thing was how he’d done it: by dropping down even further. As usual, Chad didn’t realize what had happened until afterward. Maybe it was the thinness of the air, maybe the pressure, but some invisible force, or some distant memory, had willed his arm earthward. For the first time in his life he was attacking hitters underhanded. He only knew one other guy who threw like that.

When asked how he explained his miraculous success, all Chad could say is that “the Good Lord had a plan for me.” The Good Lord’s plan, it would seem, was to illustrate to baseball players the teachings of Charles Darwin. Each time Chad Bradford was thrust into a new and more challenging environment he adapted, unconsciously, albeit not as the White Sox, or he, hoped he would adapt. When he’d been scouted by Warren Hughes, Chad’s fastball came in at around 86 mph. Hughes had sold Chad to his White Sox bosses as a guy who would grow stronger, and one day pitch sidearm, with control, at 90 mph plus. Chad himself adored the thought that he might one day throw as hard as most guys—that he would be normal. Instead, Chad came to throw underhand at between 81 and 84 mph.

Dropping his release point had various effects, but the most obvious was to reduce the distance between his hand, when the ball left it, and the catcher’s mitt. His 84-mile-per-hour fastball took about as much time to reach the plate as a more conventionally delivered 94-mile-per-hour one. Underhanded, his sinker rose before it fell, like a tennis serve with vicious topspin. Ditto his slider, which made straight for a right-handed hitter’s eye before swooping down and away. Even hitters who had faced him before fought the instinct to flinch, and found it nearly impossible to get under his pitches and lift them into the mountain air. They’d start their swing at a rising ball and finish it at a falling one. The best they could usually do with any of his pitches was to beat them into the ground. As miserable as the Canadian Rockies were for most pitchers, they might as well have been created for Chad Bradford to pitch in. No matter how thin the air, no matter how strong the outgoing breeze, it remained impossible to hit a ground ball over the wall.

Guided by some combination of the survival instinct and the failure to imagine any earthly role for himself other than Big League Pitcher, Chad Bradford dominated Triple-A hitters, even as every other pitcher on the Calgary team struggled. In a ballpark built for sluggers, he pitched fifty-one innings with an earned run average of 1.94, and gave up only three home runs. Hitters routinely complained how uncomfortable they felt against him, how hard Chad was to read, how deceptive he was. This was funny. Off the pitcher’s mound, Chad had no ability to deceive anyone about anything. He was who he was. Country. Every now and then he might try to get away with something at home—like not cleaning out the garage when he’d told his wife that he would. He simply couldn’t do it. “I’ll all but gotten away with something and then I’ll come clean,” he said. “I just hate the guilt.” On the pitcher’s mound, he had no guilt. The moment he scuffed the rubber with his foot he became a pitiless con artist, a sinister magician. He sawed pretty ladies in two, and made rabbits vanish.

He assumed, in a vague sort of way, that if he kept getting hitters out, the White Sox front office would have no choice but to call him up. He was right. Tossing a ball around with an older minor leaguer one day, he was called into the Calgary manager’s office. His new assignment: catch the first plane to Dallas. He’d join the White Sox bullpen in their upcoming series with the Texas Rangers. He went right back on the field and resumed tossing the ball around. The older player he’d been tossing with, a pitcher named Larry Casian who would retire at the end of the year, asked what the manager had wanted; and Chad told him. Casian asked why on earth Chad was out playing catch on a Triple-A field when he was meant to be flying to the big leagues. Chad said he didn’t know, and kept throwing. “I think I was in shock,” he said. Eight years after his minister and coach had showed him a trick to spare him the embarrassment of being cut from his high school team, he was getting a chance to practice it in the major leagues.

They called him into the second game of the three-game series at The Ballpark in Arlington. He didn’t feel he belonged; he felt out of his depth. “You think: how’m I gonna do this? You think it’s like a totally different game than the one you played your whole life.” He retired the first seven batters he faced, in order. The last two months of the season he pitched thirty and two-thirds innings in relief for the White Sox, and finished with an earned run average of 3.23. At one point he’d made a dozen consecutive scoreless appearances. In a season justly famous for the number of home runs hit, none were hit off Chad Bradford.

In the off-season he went back, as he always did, and always would, to Byram, Mississippi. For the first time, though he didn’t know why, he did not work out on the pitching mound his father had built, and rebuilt, for him. Dropping down and throwing sidearm had ended their games of catch. Making the big leagues severed this final dependency. He didn’t think anything of it; leaving the old mound behind was just the next thing to do. When he turned up for camp in the spring of 1999, he thought, “Great. I’m in the big leagues.”

He wasn’t. The White Sox didn’t trust Chad Bradford’s success. The White Sox front office didn’t trust his statistics. Unwilling to trust his statistics, they fell back on more subjective evaluation. Chad didn’t look like a big leaguer. Chad didn’t act like a big leaguer. Chad’s success seemed sort of flukey. He was a trickster that big league hitters were certain to figure out. The White Sox brass didn’t say any of this to Chad’s face, of course. During 1999 spring training the White Sox GM, a former big league pitcher named Ron Schueler, told Chad that his pitches weren’t moving like they used to move. He was sending Chad down to Triple-A. Chad didn’t have the nerve to say what he thought but he thought it all the same: My ball doesn’t move? But all I have is movement! When he got to Triple-A, a coach assured him that his ball moved as it always had, and that the GM just needed something to tell him other than the truth, that the White Sox front office viewed him as a “Triple-A guy.”

The Good Lord might have had a plan for Chad Bradford but apparently even He was required to respect the mystery of life behind the big league clubhouse door. For the next two years Chad pitched mainly in the minor leagues, bouncing up only briefly, and usually successfully, to the big league team. For two years he simply dominated Triple-A hitters and watched pitchers with much less impressive statistics leapfrog him. “I watched guys get called up from Double-A. I realized I was a just-in-case guy. Just in case somebody got hurt. Just in case somebody got traded. That no matter how well I did, I wasn’t going to get called up.” He talked to his wife about quitting the White Sox and going to pitch in Japan, where he might make a good living. He found that the only way he could get himself out of bed in the morning and to the ballpark was to remind himself that he wasn’t pitching only for the White Sox. “By the middle of the 1999 season I was pitching for every other big league team that might be watching,” he said. “I’m just sitting there hoping someone’s watching.”

Someone was.

THE POOL OF PEOPLE Chad Bradford didn’t know who had nevertheless found him worthy of their attention had tripled. When he was an amateur, one big league scout had taken an interest in him. As a professional, he had two more distant admirers. One was Paul DePodesta, who couldn’t quite believe that the White Sox were keeping this deadly pitching force in Triple-A, and had mentioned to Billy Beane how nice it would be if he somehow could talk the Chicago White Sox into making Chad Bradford an Oakland A. The other was a bored paralegal in Chicago named Voros McCracken. Looking for a way to ignore whatever he was meant to be doing for the Chicago law firm that he loathed working for, Voros McCracken had taken up fantasy baseball. He didn’t know it, but he was about to explain why the Chicago White Sox had so much trouble grasping the true value of Chad Bradford—and why the Oakland A’s did not.

Voros was thinking of drafting Chad Bradford for his fantasy baseball team. But before he did, he wanted to achieve a better understanding of major league pitching. Specifically, he wanted to know how you could tell if a pitcher was any good.

Voros had played baseball as a kid, and there had been a time when he had been obsessively interested in it. The moment his interest became an intellectual obsession was in 1986 when, at the age of fourteen, he picked up the most recent Bill James Abstract. He was astonished by what he found inside. “Basically, everything you know about baseball when you are fourteen years old, you know from baseball announcers,” said Voros. “Here was this guy who was telling me that at least eighty percent of what baseball announcers told me was complete bullshit, and then explained very convincingly why it was.” Voros’s interest in baseball waned in his late teens and early twenties; but when he rediscovered it, in the form of fantasy leagues on the Internet, it was in the spirit of Bill James.

The Internet of course had consequences for the search for new baseball knowledge. One of the things the Internet was good for was gathering together people in different places who shared a common interest. Internet discussion groups, and Web sites like baseballprimer and baseballprospectus, sprung up, created by young men who, as boys, had been seduced by the writings of Bill James. In one of the discussion groups, where he went to discuss what to do with his fantasy baseball team, Voros saw someone say that no matter how much research was done, no one would be able to distinguish pitching from defense. That is, no one would ever come up with good fielding statistics or, therefore, good pitching statistics. If you don’t know how to credit the fielder for what happens after a ball gets put into play, you also, by definition, don’t know how to debit the pitcher. And, therefore, you would never be able to say with real certainty how good any given pitcher was. Or, for that matter, any given fielder.

When Voros read that, “I thought, ‘That’s a stupid attitude. Can’t you do something?’ It didn’t make any sense to me that the way to approach the problem was to give up.” He tried to think about it logically. He divided the stats a pitcher had that the defense behind him could affect (hits and earned runs) from the stats a pitcher did all by himself (walks, strikeouts, and home runs). He then ranked all the pitchers in the big leagues by this second category. When he ran the stats for the 1999 season, he wound up with a list topped by these five: Randy Johnson, Kevin Brown, Pedro Martinez, Greg Maddux, and Mike Mussina. “I looked at that list,” said Voros, “and said, ‘Damn, that looks like the five best pitchers in baseball.’” He then asked the question: if his reductive approach of looking at just walks, strikeouts, and homers identified the five best pitchers in baseball, how important could all the other stuff be?

As it happened, 1999 was supposedly an “off” year for Greg Maddux. His earned run average had risen from 2.22 in 1998 to 3.57 in 1999, mainly because he gave up fifty-seven more hits in thirty-two fewer innings. Several times during the season Maddux himself mentioned that he was astonished by how many cheap hits he was giving up; but of course no one paid any attention to that. What Voros noticed was that Maddux’s hits allowed per balls put in play was far above what it usually was—in fact, it was among the highest in the big leagues. As it happened, the same year, Maddux’s teammate, pitcher Kevin Millwood, had one of the lowest hits allowed per balls in play. Even stranger, their statistics the following year were reversed. Millwood had one of the highest ratios of hits per balls in play, Maddux one of the lowest. It didn’t make any sense.

Voros asked himself another question: from year to year is there any correlation in a pitcher’s statistics? There was. The number of walks and home runs he gave up, and the number of strikeouts he recorded were, if not predictable, at least understandable. A guy who struck out a lot of hitters one year tended to strike out a lot of hitters the next year. Ditto a guy who gave up a lot of home runs. But when it came to the number of hits per balls in play a pitcher gave up, there was no correlation whatsoever.

It was then that a radical thought struck Voros McCracken:

What if the pitcher has no control of whether a ball falls for a hit, once it gets put into play?

Obviously some pitchers give up fewer hits than others, but that might be because some pitchers had more strikeouts than others, and, therefore, allowed fewer balls to be put into play. But it was generally assumed that pitchers could affect the way in which a ball was put into play. It was generally assumed that a great pitcher, like Randy Johnson or Greg Maddux, coaxed hitters into hitting the ball in a way that was less likely to become a hit. The trouble with that general assumption is that it didn’t square with the record books. There were years when Maddux and Johnson were among the worst in baseball in this regard.

If Voros McCracken was right, then what had heretofore been attributed to the skill of the pitcher was in fact caused by defense, or ballpark, or luck. But the examples of Greg Maddux and Kevin Millwood suggested that defense and ballparks might be of secondary importance. They pitched in front of the same group of fielders, and, usually, in the same ballparks. That led Voros to a second radical thought:

What if what was heretofore regarded as the pitcher’s responsibility is simply luck?

For a century and a half pitchers have been evaluated, in part, on their ability to prevent hits once the ball is put in play. A pitcher who suffered a lot of balls falling for hits gave up more earned runs and lost more games than one who didn’t. He was thought less well of than a pitcher against whom balls in play were caught by fielders. A soon-to-be unemployed young man, soon to be back living with his parents in Phoenix, Arizona, begged to differ. He was coming to the conclusion that pitchers had no ability to prevent hits, once the ball was put into play. They could prevent home runs, prevent walks, and prevent balls from ever being put into play by striking out batters. And that, in essence, is all they could do.

Voros McCracken had a radical theory. And he was staring at a lot of hard evidence supporting it.

What happened next bolsters one’s faith in the American educational system: Voros McCracken set out to prove himself wrong. He wrote a computer program that paired major league pitchers who had very similar walks, strikeouts, and home runs—but had given up very different number of hits. He located ninety such “pairs” from the 1999 season. If hits per ball in play were indeed something a pitcher could control, Voros reasoned, then the pitchers who had given up the fewer number of hits in 1999 would proceed to give up fewer hits in 2000. They didn’t. There was, in fact, no correlation from one year to the next in any given pitcher’s ability to prevent hits per balls in play.

Instead, baseball kept thrusting before Voros beguiling situations explained by his theory. A couple of months into the 2000 season, for instance, the newspapers were full of stuff about how heretofore mediocre White Sox pitcher James Baldwin, off to a great start, had somehow become the next Pedro Martinez. Voros looked more deeply at the numbers and saw that Baldwin had extremely low number of hits for the number of balls he’d put in play. His earned run average was sensational—because he’d been lucky. Sure enough, the hits started falling and Baldwin regressed to mediocrity and people stopped putting his name in the same sentence with Pedro Martinez.

For pretty much the whole of 2000 Voros McCracken, as he put it, “went looking for a reason Maddux got hit in 1999, and to this day I’m still looking for it.” At length, he penned an article revealing his findings for baseballprospectus.com. Its conclusion: “There is little if any difference among major league pitchers in their ability to prevent hits on balls hit into the field of play.” ESPN columnist Rob Neyer saw Voros’s piece and, stunned by both the quality of the thought and the force of the argument, wrote an article about Voros’s article. Several thousand amateur baseball analysts wrote in to say that Voros’s argument, on the face of it, sounded nuts. Several suggested that “Voros McCracken” might be a pseudonym for Aaron Sele, a well-hit pitcher then playing for the Seattle Mariners.

Bill James also read Rob Neyer’s article. James wrote in, and said Voros McCracken’s theory, if true, was obviously important, but that he couldn’t believe it was true. He—and about three thousand other people—then went off to disprove it himself. He couldn’t do it, and the three thousand other guys couldn’t either. About the most they could suggest was that there was a slight tendency for knuckleballers to control hits per balls in play. Nine months later, of his mammoth Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract, James laid out Voros McCracken’s argument, noted that Voros McCracken “is NekcarCcM Sorov spelled backwards,” then went on to make four points:

1. Like most things, McCracken’s argument can be taken too literally. A pitcher does have some input into the hits/ innings ratio behind him, other than that which is reflected in the home run and strikeout column.

2. With that qualification, I am quite certain that McCracken is correct.

3. This knowledge is significant, very useful.

4. I feel stupid for not having realized it 30 years ago.

One of the minor consequences of Voros McCracken’s analysis of pitching was to lead him to Chad Bradford, Triple-A pitcher for the Chicago White Sox. Voros had developed a statistic he could trust—what he called DIPS, for defense independent pitching statistic. It might also have been called LIPS, for luck independent pitching statistic, because the luck it stripped out of a pitcher’s bottom line had, at times, a more warping effect than defense on the perception of a pitcher’s true merits. At any rate, Chad Bradford’s Triple-A defense independent stats were even better than his astonishingly impressive defense dependent ones. (Chad pitched a total of 2022/3 innings in Triple-A, with an earned run average of 1.64.) And so Voros McCracken snapped up Bradford for his fantasy team, even though a player did a fantasy team no good unless he accumulated big league innings. “Basically,” said Voros, “I was waiting for someone to see what I’d seen in Bradford and put him to use.”

He waited nearly a year. Inadvertently, Voros McCracken had helped to explain why the White Sox thought of Chad Bradford as a “Triple-A guy.” There was a reason that, in judging young pitchers, the White Sox front office, like nearly every big league front office, preferred their own subjective opinion to minor league pitching statistics. Pitching statistics were flawed. Maybe not quite so deeply as hitting statistics but enough to encourage uncertainty. Baseball executives’ preference for their own opinions over hard data was, at least in part, due to a lifetime of experience of fishy data. They’d seen one too many guys with a low earned run average in Triple-A who flamed out in the big leagues. And when a guy looked as funny, and threw as slow, as Chad Bradford—well, you just knew he was doomed.

If one didn’t already know better, one might think that Voros McCracken’s article on baseballprospectus.com would be cause for celebration everywhere inside big league baseball. One knew better. Voros knew better. “The problem with major league baseball,” he said, “is that it’s a self-populating institution. Knowledge is institutionalized. The people involved with baseball who aren’t players are ex-players. In their defense, their structure is not set up along corporate lines. They aren’t equipped to evaluate their own systems. They don’t have the mechanism to let in the good and get rid of the bad. They either keep everything or get rid of everything, and they rarely do the latter.” He sympathized with baseball owners who didn’t know what to think, or even if they should think. “If you’re an owner and you never played, do you believe Voros McCracken or Larry Bowa?” The unemployed former paralegal living with his parents, or the former All-Star shortstop and current manager who no doubt owned at least one home of his own?

Voros McCracken’s astonishing discovery about major league pitchers had no apparent effect on the management, or evaluation, of actual pitchers. No one on the inside called Voros to discuss his findings; so far as he knew, no one on the inside had even read it. But Paul DePodesta had read it. Paul’s considered reaction: “If you want to talk about a guy who might be the next Bill James, Voros McCracken could be it.” Paul’s unconsidered reaction: “The first thing I thought of was Chad Bradford.”

VOROS McCRACKEN had provided the theory to explain what the Oakland A’s front office already had come to believe: you could create reliable pitching statistics. It was true that the further you got from the big leagues, the less reliably stats predicted big league performance. But if you focused on the right statistics you could certainly project a guy based on his Triple-A, and even his Double-A, numbers. The right numbers were walks, home runs, and strikeouts plus a few others. If you trusted those, you didn’t have to give two minutes’ thought to how a guy looked, or how hard he threw. You could judge a pitcher’s performance objectively, by what he had accomplished.

Chad Bradford was, to the Oakland A’s front office, a no-brainer. “It wasn’t that he was doing it differently,” said Paul DePodesta. “It was that the efficiency with which he was recording outs was astounding.” Chad Bradford had set off several different sets of bells inside Paul’s computer. He hardly ever walked a batter; he gave up virtually no home runs; and he struck out nearly a batter an inning. Paul, like Bill James, thought it was possible to take Voros’s theory too literally. He thought there was one big thing, in addition to walks, strikeouts, and home runs, that a pitcher could control: extra base hits. Chad Bradford gave up his share of hits per balls in play but, more than any pitcher in baseball, they were ground ball hits. His minor league ground ball to fly ball ratio was 5:1. The big league average was more like 1.2:1. Ground balls were not only hard to hit over the wall; they were hard to hit for doubles and triples.

That raised an obvious question: why weren’t there more successful ground ball pitchers like Chad Bradford in the big leagues? There was an equally obvious answer: there were no ground ball pitchers like Chad Bradford. Ground ball pitchers who threw overhand tended to be sinker ball pitchers and they tended to have control problems and also tended not to strike out a lot of guys. Chad Bradford was, statistically and humanly, an outlier.

The best thing of all was that the scouts didn’t like him. The Greek Chorus disapproved of what they called “tricksters.” Paul thought it was ridiculous when the White Sox sent Chad back down to Triple-A, but he could guess why they had done it. Once upon a time he had sat behind home plate while Chad Bradford pitched; he’d listened to the scouts make fun of Chad, even as Chad made fools of hitters. The guy looked funny when he threw, no question about it, and his fastball came in at between 81 and 85 mph. Chad Bradford didn’t know it, but as he dropped his arm slot, and took heat off his fastball, he was becoming an Oakland A. “Because of the way he looked, we thought he might be available to us,” said Paul. “Usually the guys who are setting off bells in my office are the guys everybody knows about. But nobody knew about this guy, because of the way he threw. If he had those identical stats in Triple-A but he threw ninety-four, there is no way they’d have traded him.”

Already Billy Beane was finding that guys he wanted magically became less available the moment he expressed an interest in them. At the end of the 2000 season he finally called the new White Sox GM, Kenny Williams, who had replaced the old White Sox GM, Ron Schueler, and said, very casually, that he was looking for “a guy who could be a twelfth or thirteenth pitcher on the staff.” Someone in the White Sox farm system. Someone maybe in Triple-A. He was willing to give up this minor league catcher in exchange for a Triple-A arm, Billy said, and he didn’t much care which one. He asked the White Sox to suggest a few names. It took Kenny Williams a while to get around to him, but finally he mentioned Chad Bradford. Said he hated to even bring Bradford up because the young man had just called in from Mississippi and said his back was hurting, and he might need surgery. “He’ll do,” said Billy.