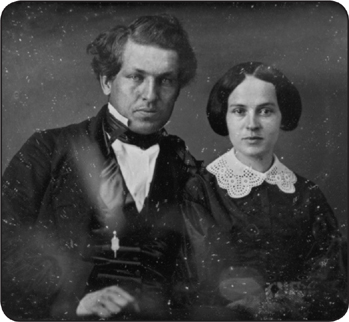

Born into abject poverty, James Garfield paid for his first year of college by working as the school’s carpenter and janitor, but so extraordinary was his academic achievement that by his second year he was promoted to assistant professor of literature and ancient languages. Just before his wedding to Lucretia Rudolph he was made the school’s president, at twenty-six years of age. (Illustration credit 1.1)

Little more than a year after he accepted a seat in the Ohio state senate, Garfield joined the Union Army to fight in the Civil War. Although his service was hailed as heroic and he was quickly promoted to brigadier general, Garfield was haunted by the memory of the young soldiers he had seen killed in battle. “Something went out of him,” he told a friend, “that never came back; the sense of the sacredness of life and the impossibility of destroying it.” (Illustration credit 1.2)

In 1876, Garfield attended the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia to see some of the world’s most ambitious scientific and artistic inventions, including the towering hand and torch that were then all that had been completed of the Statue of Liberty. Also at the exhibition were twenty-nine-year-old Alexander Graham Bell and the renowned British surgeon Dr. Joseph Lister. (Illustration credit 1.3)

At the 1880 Republican Convention, Garfield (standing center stage, right side of the photograph) gave the nominating address for John Sherman, then secretary of the treasury. Speaking to a rapt audience, Garfield, who was not a candidate himself, asked a simple question: “And now, gentlemen of the Convention, what do we want?” To his dismay and the crowd’s delight, one man shouted, “We want Garfield!”—starting a cascade of support that ended in his nomination. (Illustration credit 1.4)

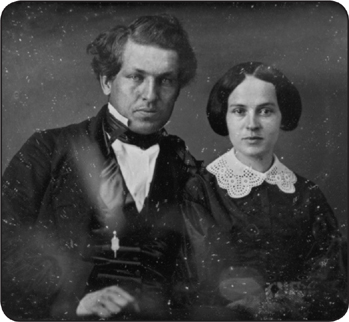

Three days after Garfield’s surprise nomination, a dangerously delusional young man named Charles Guiteau boarded the steamship Stonington for an overnight crossing from Connecticut to New York that ended tragically in a fiery maritime disaster. To Guiteau, his survival meant that he had been chosen by God for a task of great importance. (Illustration credit 1.5)

On November 2, 1880, Garfield was elected the twentieth president of the United States. Although he approached his presidency with a characteristic sense of purpose, he mourned the quiet, contemplative life he was about to lose. “There is a tone of sadness running through this triumph,” he wrote, “which I can hardly explain.” (Illustration credit 1.6)

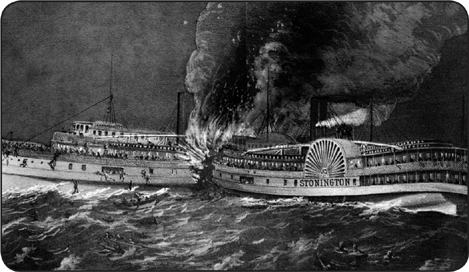

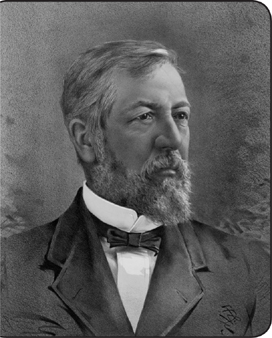

The greatest threat to Garfield’s presidency came from within his own party, in the person of Roscoe Conkling, a preening senior Republican senator from New York and arguably the most powerful man in the country. Although he expected the new president to bend to his will, Conkling found in Garfield a surprisingly unyielding opponent. “Of course I deprecate war,” Garfield wrote, “but if it is brought to my door the bringer will find me at home.” (Illustration credit 1.7)

Never comfortable in her role as first lady, Lucretia Garfield was as quiet and reserved as her husband was warm and expansive. The early years of their marriage had been difficult, but over time Garfield had fallen deeply in love with his wife. “The tyranny of our love is sweet,” he wrote to her. “We waited long for his coming, but he has come to stay.” (Illustration credit 1.8)

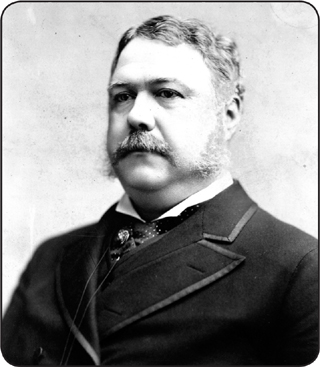

Conkling’s most loyal minion was Garfield’s own vice president, Chester Arthur. Arthur, who had been forced upon Garfield as a running mate, did nothing to disguise his loyalties, even after the election. Others bewailed his lack of credentials, noting that Arthur “never held an office except the one he was removed from.” (Illustration credit 1.9)

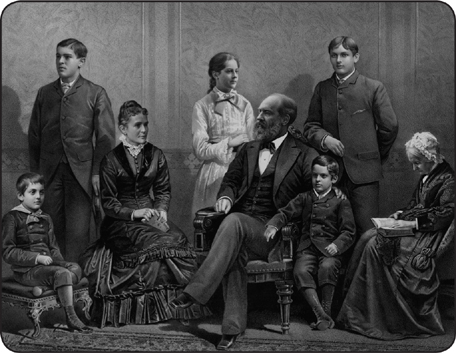

When they moved into the White House after Garfield’s inauguration, James and Lucretia brought with them their five children (from left to right: Abram, James, Mollie, Irvin, and Harry), as well as James’s widowed mother, Eliza. “Slept too soundly to remember any dream,” Lucretia wrote in her diary after her family’s first night in the White House. “And so our first night among the shadows of the last 80 years gave no forecast of our future.” (Illustration credit 1.10)

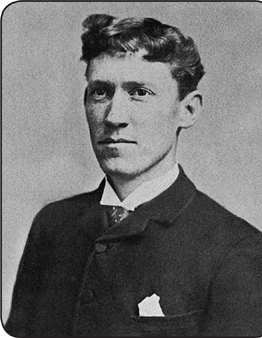

At just twenty-three years of age, Joseph Stanley Brown was the youngest man ever to hold the office of private secretary to the president. Brown’s most difficult job was keeping at bay the hoards of office seekers who demanded to see the president. “These people,” Garfield told his young secretary, “would take my very brains, flesh and blood if they could.” (Illustration credit 1.11)

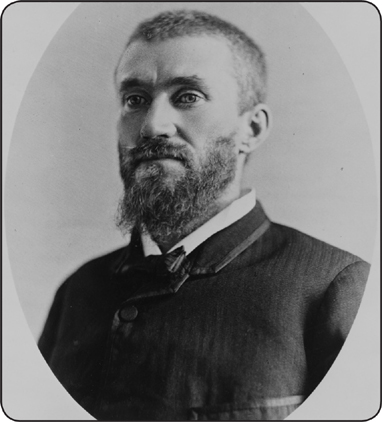

Although thousands of office seekers flooded Brown’s office, one man stood out as an “illustration of unparalleled audacity.” Charles Guiteau visited the White House and the State Department nearly every day, inquiring about the consulship to France he believed the president owed him. Finally, after months of polite but firm discouragement, Guiteau received what he felt was a divine inspiration: God wanted him to kill the president. (Illustration credit 1.12)

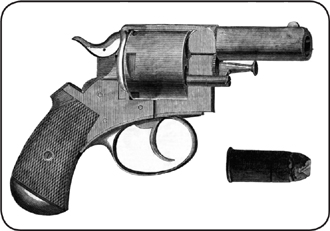

In mid-June, Guiteau, who had survived for years by slipping out just before his rent was due, borrowed fifteen dollars and bought a gun—a .44 caliber British Bulldog with an ivory handle. Having never before fired a gun, he took it to the Potomac River and practiced shooting at a sapling. “I knew nothing about it,” he said, “no more than a child.” (Illustration credit 1.13)

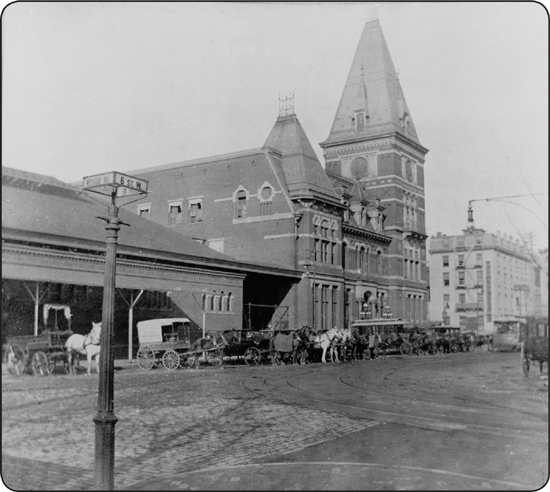

On the morning of July 2, Garfield and his secretary of state, James Blaine, arrived at the Baltimore and Potomac train station (below), where Guiteau, who had been stalking the president for more than a month, was waiting for him. The assassin’s gun was loaded, his shoes were polished, and in his suit pocket was a letter to General William Tecumseh Sherman. “I have just shot the President …,” it read. “Please order out your troops, and take possession of the jail at once.” (Illustration credit 1.14)

Just moments after Garfield and Blaine entered the waiting room, Guiteau pulled the trigger. The first shot passed through the president’s right arm, but the second sent a bullet ripping through his back. Garfield’s knees buckled, and he fell to the train station floor, bleeding and vomiting, as the station erupted in screams. (Illustration credit 1.16)

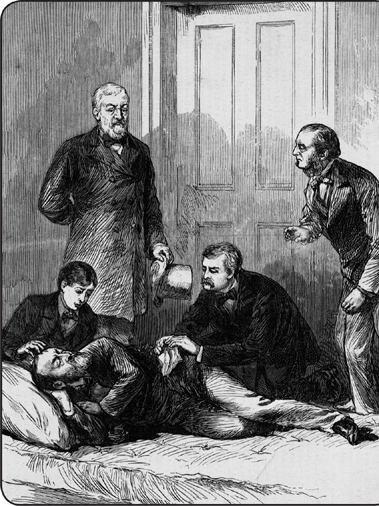

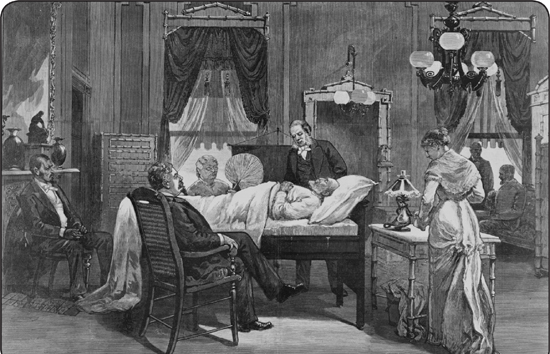

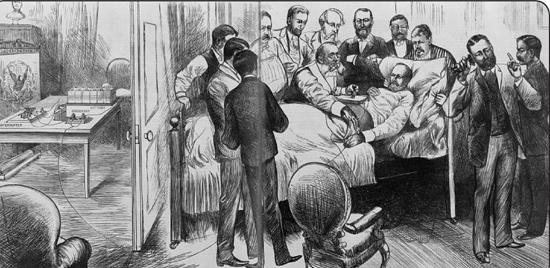

While Guiteau was quickly captured and taken into custody, Garfield was carried on a horsehair mattress to an upstairs room in the train station. Surrounded by ten different doctors, each of whom wanted to examine the president, Garfield lay, silent and unflinching, as the men repeatedly inserted unsterilized fingers and instruments into the wound, searching for the bullet. (Illustration credit 1.17)

Sixteen years before Garfield’s shooting, Joseph Lister had achieved dramatic results using carbolic acid to sterilize his operating room, and his method had been adopted in much of Europe. In the United States, however, the most experienced physicians still refused to use Lister’s technique, complaining that it was too time-consuming, and dismissing it as unnecessary, even ridiculous. (Illustration credit 1.18)

Although a crowd of nervous doctors hovered over Garfield at the train station, Robert Todd Lincoln, Garfield’s secretary of war and Abraham Lincoln’s only surviving son, quickly took charge, sending his carriage for Dr. D. Willard Bliss, one of the surgeons who had been at his father’s deathbed. Bliss, a strict traditionalist, was confident that the president could not hope to find a better physician. “If I can’t save him,” he told a reporter, “no one can.” (Illustration credit 2.1)

Soon after Garfield was brought to the White House, Bliss dismissed the other doctors, keeping only a handful of physicians and surgeons who reported directly to him. Dr. Susan Edson, one of the first female doctors in the country and Lucretia’s personal physician, insisted on staying, even though Bliss refused to let her provide anything but the most basic nursing services to the president. (Illustration credit 2.2)

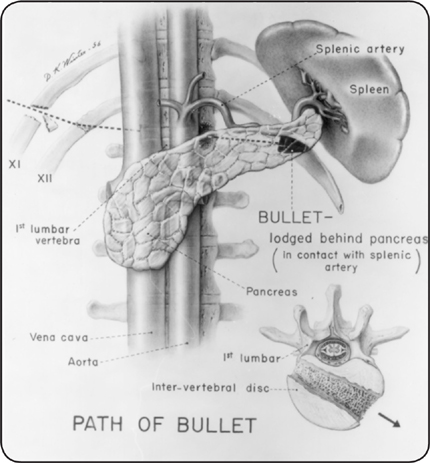

Guiteau’s bullet (first photo above), which entered Garfield’s back four inches to the right of his spinal column, broke two of his ribs and grazed an artery. Miraculously, it did not hit any vital organs or his spinal cord as it continued its trajectory to the left, finally coming to rest behind his pancreas. The bullet had done all the harm it was going to do, but Bliss had only begun. (Illustration credit 2.4)

After returning Garfield to the White House, which although crumbling and rat infested was preferable to the overcrowded hospitals, Bliss continued to search for the bullet. Garfield had survived the shooting, but he now faced an even more serious threat to his life: the infection that his doctors repeatedly introduced as they probed the wound in his back. (Illustration credit 2.5)

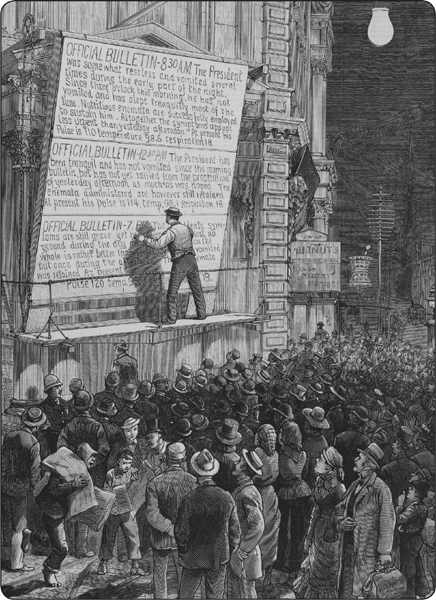

Although he allowed almost no one to visit the president, Bliss regularly issued medical bulletins, which were posted at telegraph offices and on wooden billboards outside newspaper buildings. “Everywhere people go about with lengthened faces,” one reporter wrote, “anxiously inquiring as to the latest reported condition of the president.” (Illustration credit 2.6)

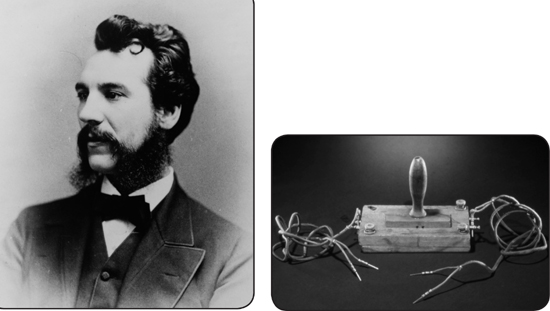

As soon as he learned of the shooting, Alexander Graham Bell (left), who had a laboratory in Washington, D.C., began to think of ways the bullet might be found. Sickened by the thought of Garfield’s doctors blindly “search[ing] with knife and probe,” he reasoned that “science should be able to discover some less barbarous method.” Bell quickly decided that what he needed was a metal detector. Four years earlier, he had invented a device to get rid of the static in telephone lines, and he now recalled that, when a piece of metal came near the invention, it caused the sound to return. Bell was confident that the invention, which he called an induction balance (right), could be modified to “announce the presence of the bullet.” (Illustration credit 2.7 and Illustration credit 2.8)

Bell (at right, with his ear to the telephone receiver) twice attempted to find the bullet in Garfield using the induction balance. Bliss, however (leaning over Garfield with the induction balance), allowed Bell to search only the president’s right side, where Bliss believed, and had publicly stated, the bullet was lodged. (Illustration credit 2.9)

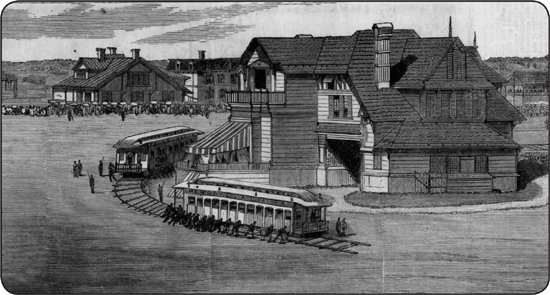

After spending two months in his sickroom in the White House, Garfield finally insisted that he be moved. A wealthy New Yorker offered his summer home in Elberon, New Jersey, and a train was carefully renovated for the wounded president. Wire gauze was wrapped around the outside to protect him from smoke, and the seats inside were removed, thick carpeting laid on the floors, and a false ceiling inserted to help cool the car. (Illustration credit 2.10)

When the train reached Elberon, it switched to a track that would take it directly to the door of Franklyn Cottage. Two thousand people had worked until dawn to lay the track, but the engine was not strong enough to breach the hill on which the house sat. “Instantly hundreds of strong arms caught the cars,” Bliss wrote, “and silently … rolled the three heavy coaches” up the hill. (Illustration credit 2.11)

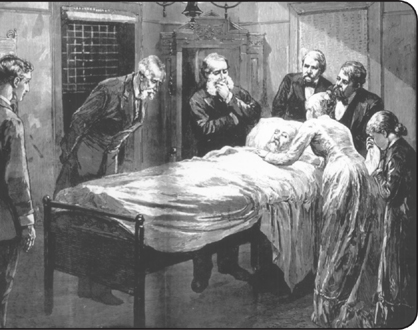

At ten o’clock on the night of September 19, Garfield suddenly cried out in pain. Bliss rushed to the room, but the president was already dying. As Garfield slipped away, “a faint, fluttering pulsation of the heart, gradually fading to indistinctness,” he was surrounded by his wife and daughter, and his young secretary, Joseph Stanley Brown—“the witnesses,” Bliss would later write, “of the last sad scene in this sorrowful history.” (Illustration credit 2.12)

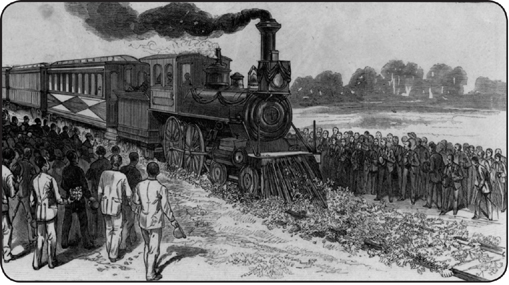

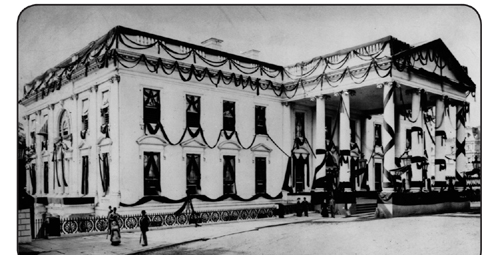

Garfield’s body was returned to Washington on the same train that had brought him to Elberon just two weeks earlier. Thousands of people lined the tracks as the train, now swathed in black, passed by. The White House was also draped in mourning, as were the buildings through which a procession of some one hundred thousand mourners wound, waiting to see the president’s body as it lay in state in the Capitol rotunda. (Illustration credit 2.13)

When news of Garfield’s death reached New York, reporters rushed to Arthur’s house, but his doorkeeper refused to disturb him. The vice president was “sitting alone in his room,” he said, “sobbing like a child.” A few hours later, at 2:15 a.m., Arthur was quietly sworn into office by a state judge in his own parlor. (Illustration credit 2.15)

After a trial that lasted more than two months, Guiteau was found guilty and sentenced to death. Twenty thousand people requested tickets to the execution. Two hundred and fifty invitations were issued. Guiteau was hanged on June 30, 1882, two days before the anniversary of Garfield’s shooting. (Illustration credit 2.16)

Had it not been for her children, “life would have meant very little” to Lucretia after her husband’s death. When this photograph was taken of the former first lady with her grandchildren in 1906, she had already been a widow for a quarter of a century. Lucretia would live another twelve years, thirty-seven years longer than James. (Illustration credit 2.17)

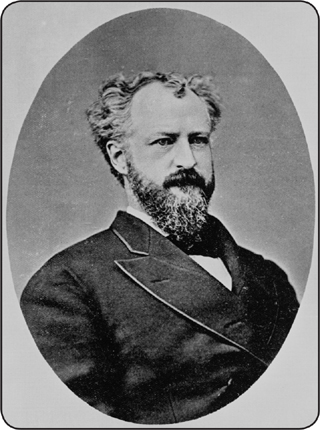

In the years following Garfield’s death, Bell continued to invent, helped to found the National Geographic Society, established a foundation for the deaf, and did what he could for those who needed him most. In 1887, he met Helen Keller and soon after helped her find her teacher, Annie Sullivan. Keller would remember her meeting with Bell as the “door through which I should pass from darkness into light.” (Illustration credit 2.18)