THOUlHfS

feu L>an Influence Others With Your Thinking!

'"FRY IT SCtf-TE TIME. Concentrate intently upon another person seated in a room with you. without his noticing it. Observe him gradually become resllcss and finally turn and fools in your direction. Simple—yd it is a positive demonstration that thought generates a mental energy which can be projected from your mind to the consciousness of another. Do you realize how much of your success and happiness in life depend upon your influencing others? Is il not important to you to have otbers understand your point of view—to be receptive to your proposals?

Demonstrable Facts

How many times have you wished there were some way you could impress .mother favorably—get across lo nim Or icr your ideas? That thoughts can be transmitted, received, and understood by others is now scientifically demonstrable. The tales of miraculous accomplishments of mind by the ancients are now known lo be fact—net fable. .TV method whereby these things can be inten tionc!!y. not accidentally, accomplished has been a sccrel long cherished by the Rosicrucians-one of the schools of ancient wisdom existing throughout the world. To thousands everywhere, lor cenhiries. the Rosicrucians have

•ar!y-lo3t art of the practical use

privately taught this o[ mind power.

This Free Book Points Out the Way

The Rosicrucians (not a religious organisation) hvvrte yi>u to explore the powers of your mind. Their sensible. simple suggestions have caused intelligent men and women lo soar to new heights of accomplishment. They tt'iff show you km lo use your natural forces and talents to do things you now think are beyond your ability. (7« l/ie tnupon beiotv and send for a copy of the fascinating sealed free book. "The Secret Heritage," which expNinj how you may receive this unique wisdom and benefit by Us application to your daify affairs.

The ROSICRUCIANS

< A M O R C )

Scribe tO. A. The Rosicrucians. AMORC. Rosicrucian Park. San Jose, California.

Kindlv send me a free copy of the W>k. 'The .Secrvl Heritage- I am interested in learning how I may receive instructions about the full use of my natural powers.

Name

Address..,

PLEASE merition Newsstand Fiction Unit when answering advertisements

(Jailing cAll Fantasy Fans!

Are there 1000 WEIRD TALES fans who will pay $2.00 per copy for the weird classics of our time — for the best of Smith, Merritt, Quinn, Howard, Bloch, Whitehead, Kuttner, etc., for an anthology of the best shorts from WT? Arkham House will publish them IF the fans will buy each book as it appears, if the fans will trust to our judgment to make the Arkham House Fantasy Library a reality, and not buy only their favorites. One or four books a year — your support will determine how many. The first book in the Arkham House Fantasy Library will be ready October 1—SOMEONE IN THE DAEK, 14 short stories, and 2 novelettes by August Derleth: $2.00 from Arkham House or your bookseller (the best of Derleth from Glory Hand to The Sandwin Compact). If only 1000 fans buy this and succeeding books, the Fantasy Library is assured. (Arkham House have left a few copies of H. P. Lovecraft's giant omnibus, THE OUTSIDER AND OTHERS, at $5.00 the copy—and a second Lovecraft omnibus on the way.)

Let us know what you think of our plan for the Arkham House Fantasy Library, which books you would like to see us publish. Write us, and send your $2.00 for SOMEONE IN THE DARK today!

ARKHAM HOUSE Sauk City, Wisconsin

1 Talked with God

(Yea, I Did—Actually and Literally)'

and as a result of that little talk with God a strings Power came into my life. After 42 years of horrible, dismal, sickening failure, everything took on a brighter hue. It's fascinating to talk with God, and it can be done very easily once you learn the secret. And when you do — well — there will come into your life the same dynamic Power which came into mine. The shackles of defeat which, bound me for .rti a-shimmering — and now—?—well, 1 own control of the largest daily newspaper in our County, I own the largest office building in our City, I drive a beautiful Cadillac limousine. I own my own home which has a lovely pipe-organ in it, and my family are abundantly provided for after I'm gone. And all this has been made possible because one day, ten years ago, I actually and literally talked with God.

You, too, may experience that strange mystical Power which comes from talking with God, and when you do, if there is poverty, unrestj

unhappiness, or ill-health in your life, well — this same God-Power is able to do for you what it did for me. No matter how useless or helpless your life seems to be — all this can be changed. For this is not a human Power I'm talking about—it's a God-Power. And there can be no limitations to lie God-Power, can there? Of course not. You probably would like to know how you, too, may talk with God, so that this same Power which brought me these good things might come into your life, too. Well'— j ust write a letter or a post-card to Dr. Frank B. Robinson, Dept. 970, Moscow, Idaho, and full particulars of this strange Teaching will be sent to you free of charge. But write now — while you are in the mood. It only costs one cent to find out, and this might easily be the most profitable one cent you have ever spent. It may sound unbelievable — but it's true, or I wouldn't tell you it was. — Advt. Copyright, 1939, Frank B. Robinson.

World's largest holders of SCIENCE FICTION PUBLICATIONS

Price lis* frets POIS, 2097 Grand Concourse. New York City

WEIRD BOOKS RENTED

Bixfcs by Loftwrsft, Morrltt, Quinn, etc., rpn'ed by mall. 3c 3 day plus postage. Write for free UK. WEREWOLF LEND1NJ LIBRARY, 227-X. So. Atlantic Avenue. Pittsburgh. Pi.

Please mention Newsstand Figtion Unit when answering advertisements

10 WEST $185

PRICESV™;

Ml Other Brandt. Cat More for Your Money |

:r:.i'.T a

LEGAL AGREEMENT _ . that dn ntM r've ]2 BlOa. SPrviie at 1/j Purchase price. Wo can do tbia because STANDARD BHANQ tin* when reconditioned with Pmi'i expert workmanship, Dnest material and sew methods do IHa

', all over tbe U.S.A. Convince younol

Mt9xi.4t-

■ 2911.60- -

■ 301-1.60- 1

. REG'D WiARRArrrV with Each Tiro 31tS.00-19S2.8S 11.15

"2x6.1X1-20 2.9S l.?&

1x6,00-81 3.IO 1.8".

2iG.50-2Q 3.20 1.8S TRUCK

,. in

I £914.75-20 2.10 ...

i.*o I.'.-:

- J 2.4S EB

i. o 2.*S i.ii

_j. j i.as J.::

25-1} 2.SO 1.16

I SOiS.'gO-

O *'o^ i? -

1 2.B0 1.15 7 2.TS LIS S 2.7S 1.15

i:J!

00- a 2.8S 1.is

Tires Tubes

.:v.-:'j 3.33

If

t'.Zb-za 6.75

K. D. TRUCK TIRES Hza Tires Tuba*

ms S3.50 JI.S5

9.65 L„

11.G0 4.15 AH Tubes Guaranteed New-AH Other Sires SendSI.OO Deposit ™ each TFreordat,d. (13.00 Depot*

on eioh Truck Tirn BisuicitC.O.D. If rem sand ea*h M(uH deduct 5%. If tr*:nl orderediooul of ok>=!l waabiD equal ralae.

POST TIRE & RUBBER CO, D*>p*.B52

4821-23 Cotta E * Grovo Avenue., CHICAGO, ILL.

High Schoo l Cours e

at Home

I many finish in 2 Yeors

your time and abilities Detroit. Course oot to resident school work—pre pares for college e exams. Standard H.8. texts aippllcd. DLploms.

rH S. subjects already coniplatHI. Sa-iel a subjects itda-■4i u4idq| adoeatioa Is yrt important for edvaDcetneat n

»do" »«.:-ia:u. D*n't : ■- t»»> ii^icffi vl toot J ETarfuate. Start TOOT CnujJloa ng». Frae

la ohlismtion.

*> American School. Dept H-739. Drex«l at 68th, Chicago

SONG POEM

WRITERS:

Send us your crIslD.il poem. Mother. Honte, Lovo. SaiTt-d. Pairintk-. c.irr.ii? <-t a.nj *ubie«. tor our rim and FREE Bhymins DialoDary «■ uacc.

RICHARD BKOTHXRS 27 Woods Building Chicago, in.

SAVE<-«50°/o

FACTORY-TO-YOU

SiBANDS !0H 6 OIAL^

5^502-° TRADE-IN

TUTL for hia FHF.F.

feKnrfBBair aw

, {(i.l-:, H,!'■(-.

3ea.alion.11r la* It SILOS to f 111.00

I. faA faaaEirfAMJI CWl 1 TUBES, PUSH-

■, Tafir-fi.

™?_fc"! laafiaw^ * | too" AEBiAl.

COMPLETE ^[WfBBJT

MIDWEST RADIO CORPORATION

FOREMEN-SHOPMEN:

WIN BIGGER

PAY

r r

■ ■

7ra//i for fAe fieffer Joos

Business—your employers—want to promote you and pay you more if you can do more. Competition, government regulations, labor problems, increasing pick-up, defense orders, and new processes have complicated their problem—their only solution is more efficient management all down the line—more capable foremen, general foremen, supervisors.superin tend-cnts. This means opportunity for you—if you can fill the bill.

Thousands of ambitious men have found in LaSalle training in "Foremanskip" or "Irtdus-l rial Management' the help they needed to step up their knowledge and ability quickly ana surely. Practical, built out of actual experience, these courses can be taken in your spare time and at moderate cost. They enable you to do your present job better and prepare you for the job ahead.

Investigate these courses. Ask for one of these free 48-page booklets. The coupon will bring it to you by mail, promptly and ? ithout obligation.

I'd like to know about you* training courses and set; if one of them fits me. Pleaae ■cod me free booklet on

□ □

Modem

Fcremarishrp Industrial

■ ■ AMI If Oept. 1075-MP

LASALLE EXTENSION UNIVERSITY A Correspondence Institution

Please mention Newsstand Fiction Unit when answering advertisements

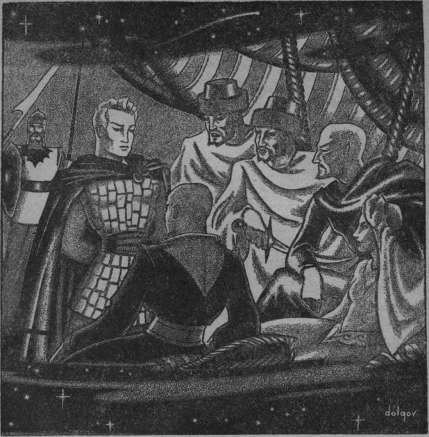

0

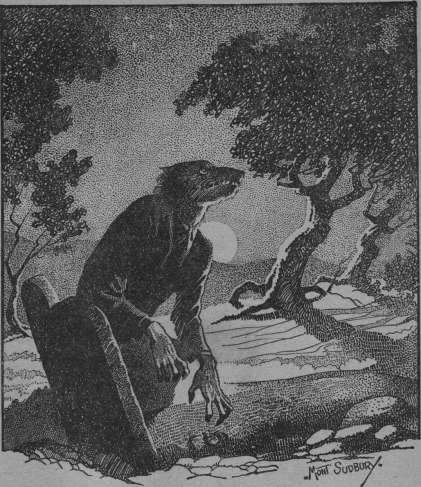

reamer's Worlds

Surely the world of Thar—its strange cities and enormous mountains,

its turquoise seas, twin moons and crimson sun — is

nothing but a dream? And yet. . .

REINING in his pony on the ridge, Khal Kan pointed down across . the other sands of the drylands that stretched in the glare of the crimson, sinking sun.

"There we are, my lads!" he announced

heartily. "See yonder black blobs on the desert? They're the tents of the dry-landers."

His tall young figure was straining in the saddle, and there was a keen anticipation on his hard, merry young face.

Swift Fantasy Novelet of a Dreamer and His Dream

EDMOND

HAMI LTON

But Brusul, the squat warrior in blue leather beside him, and little Zoor, the wizened third member of the trio, looked uneasily.

"We've no business meddling with the drylanders!" accused brawny Brusul loudly. "Your father the king said we were to scout only as far west as the Dragal Mountains. We've done that f and haven't found any sign of the cursed Bunts in them. Our business is to ride back to Jotan now and report."

"Why, what are you afraid of?" demanded Khal Kan scoffingly. "We're wearing nondescript leather and weapons —we can pass ourselves off to the dry-landers as mercenaries from Kaubos."

" Why should we go bothering the damned desert-folk at all?" Brusul demanded violently. "They've got nothing we want."

Little Zoor broke into sniggering laughter. His wizened, frog-like face was creased by wrinkles of mirth.

WEIRD TALES

"Our prince has heard of that dryland princess—old Bladomir's daughter that they call Golden Wings," he chuckled.

"I'll be damned!" exploded Brusul. "I might have known it was a woman! Well, if you think I'm going to let you endanger our lives and the success of our reconnaissance for a look at some desert wench, you-*-"

"My sentiments exactly, Brusul!" cried Khal Kan merrily, and spurred forward. His pony galloped crazily down the crimson ridge, and his voice came back to them singing.

"The Bunts came up to fotan,

Long ago!

The Bunts fled back on the homeward

track When blood did flow!"

"Oh, damn all wenches, here's an end of us because of your fool's madness," groaned Brusul as he caught up. "If those drylanders find us out, we'll make fine sport for them."

Khal Kan grinned at the brawny warrior and the wizened little spy. "We'll not stay long. Just long enough to see what she looks like—this Golden Wings the desert tribes all rave about."

They rode forward over the ocher desert. The huge red orb of the sun was full in their faces as it sank toward the west. Already, the two moons Qui and Quilus were rising like dull pink shields in the east.

Shadows lengthened colossal across the yellow sands. The wind was keen, blowing from the far polar lands of this world of Thar. Behind them rose the vast, dull red shoulders of the Dragal Mountains, that separated the drylands from their own coastal country of Jotanland.

A nomad town rose ahead, scores of flat-topped pavilions of woven black hyrk-hzit. Great herds of horses of the black desert

strain were under the care of whooping herdsboys. Smoke of fires rose along the streets.

Fierce, swarthy drylanders whose skins were darker than the bronze faces of Khal Kan and his companions, looked at the trio with narrowed eyes as they rode in. Dryland warriors fell in behind them, riding casually after them toward die big pavilion at the camp's center.

"We're nicely in the trap," grunted Brusul. "Now only wit will get us out. Which means we can't depend on you, Khal Kan."

Khal Kan laughed. "A good sword can take a man where wit will stumble. Remember, now, we're from Kaubos."

They dismounted outside the great pavilion and walked into it past cat-eyed dryland sentries.

Torches spilled a red flare over the interior of the big tent. Here along rows, on their mats, sat the chiefs of the desert folk, feasting, drinking and quarreling.

UPON a low dais sat old Bladomir, their highest chief. The old desert ruler was a bearded, steel-eyed warrior of sixty whose yellow skin was grizzled by sandstorm and sun. His curved sword leaned against his knee, and he was drinking from a flagon of purple Lurian wine.

Khal Kan's eyes flew to the girl sitting beside the chief. He felt disappointment. Was this the famous Golden Wings, this small, slight, slender dark-haired girl in black leather? Why, she was nothing much —mildly attractive with her smooth black hair and fine, golden-skinned features— but not as pretty by half as many a wench he knew.

The girl looked up. Her eyes met Khal Kan's. The stab of those midnight-black eyes was like the impact of sword-shock. For a moment, the Jotan prince glimpsed ? a spirit thrilling as a lightning-flash.

"Why, I ree now why they rave about her!" he thought delightedly. "She's a

DREAMER'S WORLDS

tiger-cat, dangerous as hell and twice as beautiful!''

Golden Wings' black brows drew together angrily at the open, insolent admiration on the face of Khal Kan. She spoke to her father.

Bladomir looked down frownlngly at the tall, grinning young warrior and his two companions.

"Watermen!" grunted the dryland chief contemptuously, using the desert-folk's name for the coast peoples. "What do you want here?"

"We're from Kaubos," Brusul answered quickly. "We had to leave there when the Bunts took our city last year. Being men without a country now, we thought we'd offer our swords to you."

Bladomir spat. "We of the desert don't need to hire swords. You can have tent-hospitality tonight. Tomorrow, be gone."

It was what Khal Kan had expected. He was hardly listening. His eyes, insolent in admiration, had never left the girl Golden Wings.

A shrill voice yelled from the drylandcrs feasting in the big torchlit tent. A thin, squint-eyed desert warrior had jumped to his feet and was pointing at Khal Kan.

"That's no Kaubian!" he cried. "It's the prince of Jotan! I saw him with the king his father, two years ago in Jotan city!"

Khal Kan's sword sang out of its sheath with blurring speed—but too late. Dry-landers had leaped on the three instantly, pinioning their arms. Old Bladomir arose, his hawk-eyes narrowing ominously.

"So you're that hell's brand, young Khal Kan of Jotan?" he snarled. "Spying on us, are you?"

Khal Kan answered coolly. "We're not spying on you. My father sent us into the Dragals to see if the Bunts were in the mountains. He feared that traitor Egir might lead the green men north that way."

"Then what are you doing here in our camp?" Bladomir demanded.

Khal Kan looked calmly at the girl. "I'd heard of your daughter and wanted to look at her, to see if she was all they say."

Golden Wing's black eyes flared, but her voice was silky. "And now that you have looked, Jotanian, do you approve?"

Khal Kan laughed. "Yes, I do. I think you're a tiger-cat as would make me a fit mate. I shall do you the honor of making you princess of Jotan."

Swords of a score of dryland warriors flashed toward the three captives, as the desert warriors leaped to avenge the insult.

"Wait!" called Golden Wings' dear voice. There was a glint of mocking humor in her black eyes as she looked down at Khal Kan. "No swords for this princeling—the whip's more suited to him. Tie him up."

A roar of applause went up from the drylanders. In a moment, Khal Kan had been strung up to a tent-pole, his hands dragged up above his head. His leather jacket was ripped off and his yellow shirt torn away.

Brusul, bound and helpless, was roaring like a trapped lion as he saw what was coming. A tall drylander with a lash had come.

Swish— crack! Roar of howling laughter crashed on the echo, as Khal Kan felt the leather bite into his flesh. He winced inwardly from the pain, but kept his insolent smile unchanged.

Again the lash cracked. And on its echo came the voice of Golden Wings, silvery and taunting.

"Do you still want me for a mate, princeling?"

"More than ever," laughed Khan Kan. "I wouldn't have a wench without spirit,"

"More!" flashed Golden Wings' furious voice to the flogger.

The lash hissed and exploded in red pain along Khal Kan's back. Still he would not flinch or wince. His mind was doggedly set.

WEIRD TALES

Through crimson pain-mists came the girl's voice again. "You have thought better of your desire now, Jotanian?"

Khal Kan heard his own laughter as a harsh, remote sound. "Not in the least, darling. For every lash-stroke you order now, you'll seek later to win my forgiveness with a hundred kisses."

"Twenty more strokes!" flared the girl's hot voice.

The whole world seemed pure pain to Khal Kan. and his back was a numbed torment, but he kept his face immobile. He was aware that the fierce laughter had ceased, that the dryland warriors were watching him in a silence tinged with respect.

The lashes ceased. Khal Kan jeered over his shoulder.

"What, no more? I thought you had more spirit, my sweet."

Golden Wings' voice was raging. "There's still whips for you unless you beg pardon for your insolence."

"No, no more," rumbled old Bladomir. "This princeling's wit-struck, it's plain to see. Tie them all up tightly and we'll send to Jotan demanding heavy ransom for them."

Khal Kan hardly felt them carrying him away to a dark, small tent, his body was so bathed in pain. He did feel the gasping agony of the jolt as he was flung down beside Brusul and Zoor.

THEY three, bound hand and foot with thongs of tough sand-cat leather, were left in the tent by guards who posted themselves outside.

"What a girl!" exclaimed Khal Kan. "Brusul, for the first time in my life, I've met a woman who isn't all tears and weakness."

"You're wit-struck, indeed!" flared Brusul. "I'd as lief fall in love with a sand-cat as that wench. And look at the mess you've got us into here! Your father await-

ing our report — and we prisoned here. Faugh.'"

"We'll get out of this some way," muttered Khal Kan. He felt a reaction of exhaustion. "Tomorrow will bring counsel—"

He heard Brusul grumbling on, but he was drifting now into sleep.

Golden Wings' face floated before him as sleep overtook him. He felt again the strong emotion with which the dryland girl had inspired him.

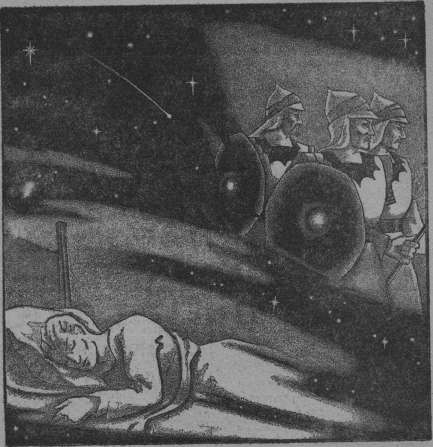

Then he was asleep, and was beginning to dream. It was the same dream as always that came quickly to Khal Kan.

He dreamed, first, that he was awaking—

HE WAS awaking—in fact, he was f.ow awake. He yawned, opened his eyes, and lay looking up at the white-papered bedroom ceiling.

He knew, as always, that he was no longer Khal Kan, prince of Jotan. He knew that he was now Henry Stevens, of Midland City, Illinois.

Henry Stevens lay looking up at the ceiling of his neat maple bedroom, and thinking of the dream he had just had— the dream in which, as Khal Kan, he had been flogged by the drylanders.

"I've got myself in a real fix, now," Henry muttered. "How am I going to get back to Jotan? But that girl Golden Wings is a darling—"

Beside him, his wife's plump figure stirred drowsily. "What is it, Henry?" she asked sleepily.

"Nothing, Emma," he replied dutifully. He swung out of bed. "You don't need to get up. I'll get my own breakfast."

On slippered feet, Henry Stevens plodded across the neat bedroom. As he carefully shaved, his mind was busy with remote things.

"Even if Jotan can pay the ransom, it'll be a week before I can get back there," he

DREAMERS WORLDS

11

thought "And who knows what the Bunts will be up to in that time?"

Out of the mirror, his own newly-shaven face regarded him. It was the thin, commonplace face of Henry Stevens, thirty-year-old insurance official of Midland City —a face fa?* different from Khal Kan's hard, bronzed, merry visage.

"I suppose I*m crazy to worry about Jo-tan, when it may be all a dream," Henry muttered thoughtfully. "Or is it this that's the dream, after all? Will I ever know?"

He was facing the mystery that had baffled him all his life.

Was Khal Kan a dream—or was Henry Stevens the dream?

All his life, Henry Stevens had been beset by that riddle. It was one that had begun with his earliest childish memories.

As far back as he could remember, Henry had had the dream. As a child, he had every night dreamed that he was a child in a different world far removed from Midland City.

Each night, when little Henry Stevens had lain down to sleep, he had at once slipped into the dream. In that dream, he was a boy in the city Jotan, on the shore of the .Zambrian Sea, on the world of Thar. He was Khal Kan, prince of Jotan, son of the king, Kan Abul.

All through his years of youth and manhood, the dream had persisted. Every night, as soon as he slept, he dreamed that he was awaking. And then, in the dream, he seemed to be Khal Kan again. As Khal Kan, he lived through the day on Thar. And when Khal Kan lay down to sleep, he dreamed that he awoke as Henry Stevens, of Earth!

The dream was continuous. There was nothing incoherent or jerky about it. Day followed day consecutively in the life of Khal Kan, as logically as in the life of Henry Stevens.

Henry Stevens grew up through boyhood and youth, attending his school and

playing his games and going off to college, and finally getting a job with the insurance company, and marrying.

And each night, in Henry's dream Khal Kan was similarly pursuing his life—was learn ing to ride and wieid a sword, and explore the mountains west of Jotanland, and go forth in patrol expeditions against the hated Bunts of the south who were the great enemies of Jotan.

When he was awake and living the life of Henry Stevens, it always seemed to him that Khal Kan and his colorful, dangerous world of Thar were nothing but an extraordinarily vivid dream. All that world, with its strange cities and enormous mountains and forests and alien races, its turquoise seas and crimson sun, were surely nothing but dream.

That was how it seemed to Henry Stevens. But when he was Khal Kan, in the nightly dream, it was exactly the opposite. Then it seemed to Khal Kan that Henry Stevens and his strange world of Earth were the dream.

Khal Kan seldom doubted that. The hardy young prince of Jotan knew there could be no such world as this Earth he dreamed about each night. A world where he was a timid little man who worked with papers at a desk all day long, a world where men dressed and acted differently, where even the sun was not red but yellow. Surely, Khal Kan thought, that could be nothing but a dream that somehow had oppressed him all his life.

Henry Stevens was, not so sure about which was real. There were many times when it seemed to Henry that maybe Thar was the real world, and that Earth and Henry Stevens were die dream.

They couldn't bodi be real! One of these existences of his must be the real one, and the other a strange continued dream. But which?

"If I only knew that," Henry muttered to his reflection in the mirror. "Then,

WEIRD TALES

whichever one is the dream, wouldn't bother me much—I'd know that it wasn't real, whatever happened."

He looked ruefully at himself. "As it is, I've got two lives to worry about. Not that Khal Kan does much worrying!"

His puzzled reverie was broken by the sleepy voice of his wife, calling a mechanical warning from the bedroom.

"Henry, you'd better hurry or you'll be late at the office."

"Yes, Emma," he replied dutifully, and hastened his toilet.

He loved his wife. At least, Henry Stevens loved her—whether or not Henry was real.

"OUT Golden Wings! There was a girl! -*-' His pulse still raced as he remembered her beauty, when he had seen her through Khal Kan's eyes.

How the devil was Khal Kan going to get out of the trap into which the girl's beauty had led him?

He couldn't guess what the reckless young prince would do—for Khal Kan and Henry Stevens had nothing in common in their personalities.

"Oh, forget it!" Henry advised himself irritably. "Thar must be a dream. Let Khal Kan worry about it, when the dream comes back tonight."

But he couldn't forget so easily. As he drove to town in his sedate black coupe, he kept turning the problem over in his mind. And he found himself brooding about it that afternoon over his statements, at his desk in the big insurance office.

If Khal Kan didn't get away, his father might send an expedition out of Jotan to search for him. And that would weaken Jotan at a time when the Bunts were menacing it. He must—

"Stevens, haven't you finished that Blaine statement yet?" demanded a loud voice beside his desk.

Henry started guiltily. It was Carson,

the wasp-like little office manager, who stood glowering down at him.

"I—I was just starting it," Henry said hastily, grabbing the neglected papers.

"Just starting it?" Carson's thin lips tightened. "Stevens, you've got to pull yourself up. You're getting entirely too dreamy and inefficient lately. I see you sitting here and staring at the wall for hours. What's the matter with you, anyway? "

"Nothing, Mr. Carson," Henry said panically. Then he amended, "I've had a few troubles on my mind lately. But I won't let them interfere with my work again."

"I wouldn't, if I were you," advised the waspish little man ominously, and departed.

Henry felt a cold chill. There had been a significant glitter in Carson's spectacled eyes. He sensed himself on the verge of a terrifying precipice—of losing his job.

"If I don't forget about Thar, I will be in trouble," he muttered to himself. "I can't go on this way."

As he mechanically added figures, he was alarmedly trying to figure out a way to rid himself of this obsession.

If he only knew which was reality and which was dream! That was what his mind always came back to, that was the key of his troubles.

If, for instance, he could learn for a certainty that Khal Kan and his life in Thar were merely a dream, as they seemed, then he wouldn't brood about them. There wouldn't be any point in worrying about what happened in a dream.

On the other hand, if he should learn that his life as Khal Kan was real, and that Henry Stevens and his world were the dream, then that too would relieve his worries. It wouldn't matter much if Henry Stevens lost his job—if Henry were only i dream.

Henry was fascinated, as always, by that

DREAMER'S WORLDS

13

thought. He looked around the sunlit

.office, the neat desks and busy men and

' girls, with a flash of derisive superiority.

You may none of you be real at all," he

thought. "You may all just be part of

Khal Kan's nightly dream."

That was always a queer thought, that idea that Earth and all its people, including himself, were just a dream of the prince of Jotan.

"I wish to heaven I knew," Henry muttered baffledly for the thousandth time. "There must be some way to find out which is real."

Yet he could see no test that would give proof. He had thought of and had tried many things during his life, to test the matter.

Several times, he had stayed up all night without sleep. He had thought that if he did not sleep and hence did not dream, it would break the continuity of the dream-life of Khal Kan.

But it had had no effect. For when he finally did sleep, and dreamed that he awoke as Khal Kan, it merely seemed to Khal Kan that he had dreamed he was Henry Stevens, staying up a night without sleep—that he had dreamed two days and a night of the unreal life of Henry Stevens.

No, that had failed as a test. Nor was there any other way. If he could be sure that while he was sleeping and living the dream-life of Khal Kan, the rest of Earth remained real—that would .solve the problem.

The other people of Earth were sure they had remained in existence during his sleep. But, if they were all just figments of dream, their certainty of existence was merely part of the dream.

It was maddening, this uncertainty! He felt that it would drive him to insanity if the puzzle persisted much longer. Yet how was he to solve the riddle?

"Maybe a good psychoanalyst," Henry

thought doubtfully. "A fellow like that might be able to help."

He shrank from his own idea. It would mean telling the psychoanalyst all about his dream-life. And that was something he had not done for years, not since he was a small boy.

When he was a boy, Henry Stevens had confidendy told his family and chums all about his strange dreams—how each night when he slept he was another boy, the boy Khal Kan in Jotan, on the world Thar. He had told them in detail of his life as Khal Kan, of the wonderful black city Jotan, of the red sun and the two pink moons.

His parents had at first laughed at his stories, then had become worried, and finally had forbidden him to tell any more such falsehoods. They had put it all down to a too-vivid imagination.

And his boyhood chums had jeered at his tales, admiring his ability as a liar but rudely expressing their opinions w r hen he had earnestly maintained that he did dream it all, every night.

So Henry had learned not to tell of his dream-life. He had kept that part of his life locked away, and even Emma had never heard of it.

"But still, if a psychoanalyst could help me find out which is real," he thought desperately, "it'd be worth trying—"

THAT afternoon when his work was finished, Henry found himself entering the offices of a Doctor Willis Thorn whom he had heard of as the best psychoalanlyst in the city. He had made an appointment by telephone.

Doctor Thorn wis a solidly built man of forty, with the body of a football player, and calm, friendly eyes. He listened with quiet attention as Henry Stevens, slowly at first and then more eagerly, poured out his story.

"And you say the dream continues log-

WEIRD TALES

ically, from night to night?" Doctor Thorn asked. "That's strange. I've never heard of a psychosis quite like thai."

"What I want to know is—which is real?" Henry blurted. "Is there any way in which you could tell me whether it's Thar or Earth that's real?"

Doctor Thorn smiled quietly. "I'm not a figment of a dream, I assure you. You see me sitting here, quite real and solid. Too solid, I'm afraid—I've been putting on weight lately."

Henry, puzzledly thoughtful, missed the pleasantry. "You seem real and solid," he admitted, "and so does' this office and everything else, to me. But then I, Henry Stevens, may only be a part of the dream myself—Khai Kan's dream."

Doctor Thorn's brow wrinkled. "I see your point. It's logical enough, from a certain standpoint. But it's also logical that you and I and Earth are real, and that Khal Kan and his world are only an extraordinarily vivid dream your mind has developed as compensation for a monotonous life."

"I don't know," Henry muttered. "When I'm Khai Kan, I'm pretty sure that Henry Stevens is just a dream. But I, Henry Stevens, am not so sure. Of course, Khal Kan isn't the kind of man to brood or doubt much about anything — he's a fighter and reckless adventurer."

Doctor Thorn was definitely interested. "Look here, Mr. Stevens, suppose you write out a complete history of this dream-life of yours—this life as Khal Kan—and bring it with you the next time. It may help me."

Henry left the office, with his new hope on the wane. He didn't think the psychoanalyst could do much to solve his problem.

After all, he thought depressedly as he drove homeward, there was hardly any way in which you could prove that you really existed. You felt you did exist, everyone

around you was sure they did too, but there was no real proof that that whole existence was not just a dream.

His mind came back to Khal Kan's present predicament. How was he going to escape from the drylanders? He brooded on that, through dinner.

"Henry Stevens, you haven't been listening to one word!" his wife's voice aroused him.

Emma's plump, good-natured face was a little exasperated as she peered across the table at him.

"I declare, you're getting more dopey every day!" she told him snapffily.

"I'm just sleepy, I guess," Henry apologized. "I think I'll turn in."

She shook her head. "You go to bed earlier every night. It's not eight o'clock yet."

Henry finally was permitted to retire. He felt an apprehensive eagerness as he undressed. What was going to happen to Khal Kan?

He stretched out and lay in the dark room, half dreading and half anticipating the coming of sleep. Finally the dark tide of drowsiness began to roll across his mind.

He knew vaguely that he was falling asleep. He slipped into darkness. And, as always, the dream came at once. As always, he dreamed that he was awaking—

KHAL KAN awoke, in the dark, cold tent. His whole back was a throbbing pain, and his bound arms and legs were numb.

He lay thinking a moment of his dream. How real it always seemed, the nightly dream in which he was a timid little man named Henry Stevens, on a queer, drab world called Earth! When he was dreaming—when he was the man Henry Stevens —he even thought that he, Khal Kan, was a dream!

Dreams within dreams—but they meant

DREAMER'S WORLDS

If

nothing. Khal Kan had long ago quit worrying about his strange dream-life, The wise men of Jotan whom he had consulted had spoken doubtfully of witchcraft Their explanations had explained nothing. And life was too short, there were too many enemies to slay and girls to kiss and flagons to drink, to worry much about dreams.

"But this is no dream, worse luck!" thought Khal Kan, testing his bonds. "The prince of Jotan, trussed up like a damned hyrk —"

He stiffened. A shadow was moving toward him in the dark tent. It bent over him and there was a muffled flash of steel. Amazedly, Khal Kan felt the bonds of his wrists and ankles relax. They had been cut.

The shadow sniggered. "What would you do without little Zoor to take care of you, Prince?"

"Zoor?" Khal Kan's whisper was astonished. "How in the name of—"

"Easily, Prince," sniggered Zoor. "I always carry a flat blade in the sole of my sandal. But it took me all night to get it out and cut myself free. It's almost dawn."

The cold in the tent was piercing. Through a crack in the flap, Khal Kan could see the eastern sky beginning to pale a little. He could also hear the drylanders on guard out there, shuffling to keep warm.

Khal Kan got to his feet while Zoor was freeing Brusul. Then the little man used his sliver of steel to slice a rip through the back wall of the tent. They three slipped out into the starry darkness.

Khal Kan chuckled a little to himself as he remembered how his dream-self—the man Henry Stevens in that dream-world-had worried about his plight. As though there was anything worth worrying about in that.

They did not stop for a whispered consultation until they were well away from the tent in which they had been kept. The

whole camp of the drylanders was still, except for an occasional drunken warrior staggering between the dark tents, and the stamping of tethered horses not far away.

"The horses are this way," muttered Brusul. "We can be over the Dragals before these swart-skinned devils know we're gone."

"Wait!" commanded Khal Kan's whisper. "I'm not going without that girl. Golden Wings."

"Hell take your obstinacy!" snarled Brusul. "Do you think you can steal the drylanders' princess right out of their camp? They'd chase us to the end of the world. Beside, what would you want with that little desert-cat who had you flogged raw?"

Khal Kan uttered a low laugh. "She's the only wench I've ever seen who was more than a sweet armful for an idle hour. She's flame and steel and beauty—and by the sun, I'm taking her. You two get horses and 'wait by the edge of the camp yonder. I'll be along."

He hastened away before they could voice the torrent of objections on their lips. He had taken Zoor's hiltless knife.

Khal Kan made his way through the dark tents to the big pavilion of the dryland chief. He silently skirted its rear wall, stopping here and there to slash the wall and peer inside.

Thus he discovered the compartment of the pavilion in which the girl slept. It had a guttering copper night-lamp whose flickering radiance fell on silken hangings and on a low mass of cushions on which she lay.

Golden Wings' dark head was pillowed on her arm, her long black lashes slumbering on her cheek. Coolly, Khal Kan made an entrance. He delayed to cut strips from the silken hangings, and then approached her.

His big hand whipped the silken gag around Golden Wings' mouth and tied it before she was half-awake. Her eyes blaz-

WEIRD TALES

ing raging as she recognized him, and her slim silken figure struggled in his grasp with wildcat fury.

Khal Kan was rough and fast. He got the silken bonds around her hands and feet, and then drew a breath of relief.

"Now we ride for Jotan, my sweet," he whispered mockingly to her as he picked up her helpless figure.

Golden Wings" black eyes blazed into his own, and he laughed.

He kissed her eyelids. "This will have to serve as proof of my affections until we can take this damned gag off, my dear," he mocked.

TTER firm body writhed furiously in his ■*•-■- grasp as he went out into the starry night. Silently, bearing the girl easily, he made his way through the sleeping camp.

Stamping shadows loomed up at the camp edge, awaiting him. Brusul and Zoor had horses, and the little spy handed Khal Kan a stolen sword.

"You have the girl!" Zoor sniggered. "Even I could not make a theft so daring —to steal the drylanders' princess out of their own camp!"

"We haven't got her out yet, and it's far to Jotan," snarled Brusul. "Let's get out of here."

Khal Kan vaulted into the saddle and drew Golden Wings' struggling silken figure across the saddle-bow. They walked their horses softly eastward till they were out of earshot of the camp, and then they spurred into a gallop.

The cold dawn wind whistled past Khal Kan's face. Far ahead, the black bulk of the Dragals loomed against the paling sky.

He took the gag from Golden Wings' mouth. In the growing light, the cold anger of the girl's face flared at him.

"Dog of Jotan!" she panted. "You'll be staked out in the desert to die the sun-death, for this crime."

"I didn't free your mouth for words,

my dear," replied Khal Kan. "But for this—"

Her lips writhed under his kiss. His laughter pealed bade on the wind as he straightened again in the saddle.

Golden Wings sobbed with rage. "You'll not be killed at once," she promised breathlessly. "It will take time to think up a death appropriate for you. Even the sun-death would be too easy."

"That's the way I like to hear a girl talk," applauded Khal Kan. "Hell take these wenches who are all softness and whimpers. We'll get along, my pet."

They were still far from the first ridges of the Dragals when the crimson sun came up to light their way. Brusul turned his battered face back to stare across the ocher sands, and then swore and pointed to a remote, low wisp of dust back on the western horizon.

"There the)' come! They're following our tracks, curse them!"

"We can lose them when we reach the mountains," Khal Kan called easily. "Faster!"

"You'll never reach the Dragals," taunted Golden Wings, eyes sparkling now. "My father's horses are swift, Jotan dogs!"

They spurred on. The first low red ridges of the Dragals seemed tantalizingly far away. The sun was rising higher, and its blistering heat had already dispelled the coolness of dawn.

The crimson orb hung almost directly overhead, and they were still hours from the ridges, when Zoor's pony tripped and went down. It rolled with a broken neck as the little man darted nimbly from the saddle.

Khal Kan reined up and came riding back. The dust-cloud of their pursuers was ominously big and close.

"Ride en!" Zoor cried, his wizened face unperturbed. "You can make the ridges without me."

DREAMER'S WORLDS

17

"We caribt, make them," Khal Kan denied coolly. "And it's not our way to separate in face of danger."

He dismounted. Golden Wings was looking westward with exultation in her black eyes. "Did I- not tell you I'd see you caught!" she cried.

Khal Kan cut free her hands and feet. He reached up and set his lips against hers, bruisingly. Then he stepped back, releasing her.

"You can ride back and meet your father's warriors with the glad news that we're here for the taking, my sweet," he told her.

"You're letting Jier go?" yelled Brusul. "We could hold her hostage."

"No," declared Khal Kan. "I'll not see her harmed in the fight."

He laughed up at her, as she sat in the saddle looking down at him with wide, strangely bewildered eyes.

"Too bad I couldn't get you to Jotan with me, my little desert-cat. "But you'll have the pleasure of seeing us killed. Tell your father's warriors to come with their swords out!"

TT^'OR a long moment, Golden Wings -"- looked down at him. Then she set spur to the pony and galloped away to the oncoming dust-cloud.

Khal Kan and his two comrades drew their swords and waited. And soon they saw the force of a hundred drylanders riding up to them. Bladomir was in the lead, his beard bristling. And Golden Wings rode beside him.

"The little hell-cat wants to help kill us," growled Brusul. "You should have slit her throat."

Khal Kan shrugged. "I'd liefer slit my own. Too bad we have to end in a skirmish like this, old friends. I dragged you into it."

"Oh, it's all right, except that we won't be with the armies of Jotan when they go

out to meet Egir and the Bunts," muttered Brusul.

The drylanders were not charging. No sword was unsheathed as they came forward, though old Bladomir was frowning blackly. The desert chieftain halted his horse ten paces away, and spoke to Khal Kan in a roaring voice.

"I ought to kill you all, Jotanians, for taking my daughter away with you. But we're a free people. Since she says she goes with you of her own free will, I'll not interfere."

"Of her own free will?" gasped Brusul. "What in the sun's name—"

GOLDEN WINGS had dismounted and came toward Khal Kan. Her dark eyes met him levelly. She did not speak, nor did he, as she took his hand.

Bladomir laid a sword-blade across their clasped hands, and tossed a handful of the yellow desert sand upon it. Khal Kan felt his heart in his throat. It was the marriage rite of the drylanders.

Zoor and Brusul were staring unbelievingly, the drylanders sadly. But Golden Wings' red lips were sweet fire under his mouth.

"You said that for each lash-stroke last night, I'd pay a hundred kisses," she whispered. "That will take long—my lord,"

He looked earnestly into the brooding sweetness of her face. "No deceptions between us, my little sand-cat!" he said. "When I freed you and let you go to your father, I was gambling that you'd come back—like this."

For a moment her eyes flared surprise and anger. And then she laughed. "No deceptions, my lord! Last night, in my father's pavilion, I knew you were the mate I'd long awaited. But—I thought the lashing would teach you to value me the more!"

Bladomir had mounted his horse. The stoical old desert chieftain and his men

WEIRD TALES

called their farewells, and then rode back westward.

They had left horse and sword for Golden Wings. She rode knee to knee with Khal Kan as they spurred up the sloping sands toward the first red ridges of the Dragals.

Dusk came upon them hours later as they climbed the steep pass toward the highest ridge of the range. One of the pink moons was up and the other was rising. The desert was a vague unreality far behind and below.

"Look back and you can see the camp-fires of your people,"' he told the girl.

Her dark head did not turn. "My people are ahead now, in Jotan."

They topped the ridge. A yell of horror burst from Brusul.

"The Bunts are in Galoon! Hell take the green devils—they've marched leagues north in the last two days!"

Khal Kan's fierce rage choked him as he too saw. Far, far to the east beneath the rosy moons, the lowland plain below the Dragals stretched out to the silvery immensity of the Zambrian Sea.

Down there to the right, on the coast, should have shone the bright lights of the city Galoon, southern most port of Jotan-land.

But instead the city was scarred by hideous red fires, that smoldered through the night like baleful, unwinking eyes.

"Egir's led the green men farther north than I dreamed!'" Khal Kan muttered. "Oh, damn that traitor! If I had my sword at his throat—"

"We'd best ride hard for Jotan before we're cut off," Zoor cried.

They rode north along the ridges, until the red fires of burning Galoon receded from sight. Then they moved down the wesiern slopes of the mountains, and galloped on north along the easier coast road.

Galloping under the rosy moons, Khal Kan pointed far along the shore to a yellow

beacon-fire atop the lighthouse tower outside Jotan.

The square black towers of Jotan loomed sheer on the edge of the silver sea, surrounded by the high black wall which had only two openings—a big water-gate on the sea side, and a smaller gate on the other. The rosy moonlight glinted off the arms of sentries posted thick on the wall, and a sharp challenge was flung down as Khal Kan rode up to the closed gate.

Joyful cries greeted the disclosure of his identity. The gates ground slowly open, and he and Golden Wings galloped in with Brusul and Zoor. Khal Kan led the way through the black-paved stone streets of Jotan to the low, brooding mass of the palace.

When, with Golden Wings' hand in his, he hurried into the great domed, torchlit marble Hall of the Kings, he found his father awaiting him.

Kan Abul's iron-hard face seemed even grimmer than usual.

"The Bunts—" Khal Kan began, but the king finished for him.

"I know—the green men have captured and sacked Galoon, led by my traitorous brother. We've been gathering our forces. Tomorrow we march south to attack—it's good you*re in time to join us. But who's this?"

Khal Kan grinned. "I found no Bunts over the Dragais, but I did find a princess for Jotan. They call her Golden Wings— Bladomir's daughter."'

Kan Abul grunted. "A dryland princess? Well, you've made a bad bargain, girl—this son of mine's an empty-skulled rascal. And tomorrow he goes south with us to battle.''

"And I go with him!" declared Golden Wings. "Do you think I'm one of your Jotan girls that cannot ride or fight?"

Khal Kin Lmghed. "We'll argue that the morrow."

Later that night, in his great chamber of

DREAMER'S WORLDS

!9

seaward windows, with Golden Wings sleeping in his arms, Khal Kan also slept—

HENRY STEVENS brooded as he sat waiting in the office of the psychoanalyst, the next afternoon. Things couldn't go on this way! He'd been reprimanded twice this day by Carson for ne-gleet of his work.

Since he'd awakened this morning, the danger to Jotan had been obsessing his thoughts.

It was queer, but he had had more time to reflect upon the peril than had Khal Kan himself in the dream.

"You can go in now, Mr. Stevens," smiled the receptionist.

Doctor Thorn's alert young eyes caught the haggardness of Henry's face but he was casual as he pushed cigarettes across the desk.

"You had the same dream last night?" he asked Henry.

Henry Stevens nodded. "Yes, and things are getting worse—over there in Thar. The Bunts have taken Galoon in some way, and Egir must be planning to lead them on against Jotan."

"Egir?" questioned the psychoanalyst.

Henry explained. "Egir was my—I mean Khal Kan's — uncle, the younger brother of Kan Abul. He's a renegade to Jotan. He fled from there about—let's see, about four Thar years ago, after Kan Abul discovered his plot to usurp the throne. Since then, he's been conspiring with the Bunts."

Henry took a pencil and drew a little map on a sheet of paper. It showed a curving, crescent-like coast.

"This is the Zambrian Sea," he explained. "On the north of this indented gulf is Jotan, my city—I mean, Khal Kan's city. Away to the south here across the gulf is Buntland, where the barbarian green men live. On the coast between Buntland and Jotan are the independent

city of Kaubos and the southernmost Jo-tanianVity of Galoon.

"When my uncle Egir fled to the Bunts," Henry went on earnestly, "he stirred them up to attack Kaubos, which they captured. We've been planning an expedition to drive them out of there. Five days ago I rode over the Dragal Mountains with two comrades to reconnoiter a possible route by which we could make a surprise march south. But now the Bunts are moving north and have sacked Galoon. There's a big battle coming—"

Henry paused embarrassedly. He had suddenly awakened from his intense interest in exposition to become aware that Doctor Thorn was not looking at the map, but at his face.

"I know it all sounds crazy, to talk about a dream this way," Henry mumbled. "But I can't help worrying about Jotan. You see, if it turned out that Thar was real and that this was the dream—"

He broke off again, and then finished with an earnest plea. "That's why I must know which is real—Thar or Earth, Khal Kan or myself!"

Doctor Thorn considered gravely. The young psychiatrist did not ridicule Henry's bafflement, as he had half expected.

"Look at it from my point of view," Thorn proposed. "You think it's possible that I may be only a figment in a world dreamed by Khal Kan each night. But I know that I'm real, though I can't very well prove it."

"That's it," Henry murmured discout-agedly. "People always take for granted that this world is real—they never even imagine that it may be just a dream. But none of them could prove that it isn't a dream."

"But suppose you could prove that Thar is a dream?" Thorn pursued. "Then you'd know that this must be the real existence."

Henry considered. "That's true. But how can I do that?"

WEIRD TALES

"I want you to take this memory across into the dream-life with you tonight," Doctor Thorn said earnestly. "I want you, when you awake as Khal Kan, to say over and over to yourself—'This isn't real. I'm not real. Henry Stevens and Earth are the reality'."

"You think that will have some effect?" Henry asked doubtfully.

"I think that in time your dream-world will begin to fade, if you keep saying that," the psychoanalyst declared.

"Well, I'll try it," Henry promised thoughtfully. "If it has any effect, I'll be sure then that Thar is the dream."

Doctor Thorn remarked, "Probably the best thing to happen would be if Khal Kan got himself killed in that dream-life. Then, the moment before he 'died,* the dream of Thar would vanish utterly as always in such dreams."

Henry was a little appalled. "You mean —Thar and Jotan and Golden Wings and all the rest would be gone forever?"

"That's right—you wouldn't ever again be oppressed by the dream," encouraged the psychoanalyst.

Henry Stevens felt a chill as he drove homeward. That was something he hadn't forseen, that the death of Khal Kan in that other life would destroy Thar forever if Thar was the dream.

Henry didn't want that. He had spent just as much of his life in Thar, as Khal Kan, as he had done here on Earth. No matter if that life should turn out to be merely a dream, it was real and vivid, and he didn't want to see it utterly destroyed. He felt a little panic as he pictured himself cut off from Thar forever, never again riding with Brusul and Zooc on crazy adventure, never seeing again that brooding smile in Golden Wings' eyes, nor the towers of Jotan brooding under the rosy moons.

Life as Henry Stevens of Earth, without his nightly existence in Thar, wojdd be

tame and profitless. Yet he knew that he must once and for all settle the question of which of his lives was real, even though it risked destroying one of those lives.

"I'll do what Doctor Thorn said, when I'm Khal Kan tonight," Henry muttered. "I'll tell myself Thar isn't real, and see if it has any effect."

He was so strung up by anticipation of the test he was about to make, that he paid even less attention than usual to Emma's placid account of neighborhood gossip and small household happenings.

That night as he lay, waiting for sleep, Henry repeated over and over to himself the formula that he must repeat as Khal Kan. His last waking thought, as he drifted into sleep, was of that.

KHAL KAN awoke with a vague sense of some duty oppressing his mind. There was something he must do, or say—

He opened his eyes, to look with contentment upon the dawn-lit interior of his own black stone chamber in the great palace at Jotan. On the wall were his favorite weapons—the sword with which he'd killed a sea-dragon when he was fourteen years old, the battered shield with the great scar which he had borne in his first real battle.

Golden Wings stirred sleepily against him, her perfumed black hair brushing his cheek. He patted her head with rough tenderness. Then he became aware of the tramp of many feet outside, of distant clank of arms and hard voices barking orders, and rattle of hurrying hoofs.

His pulse leaped. "Today we go south to meet Egir and the Bunts!"

Then he remembered what it was that dimly oppressed his mind. It was something from his dream—the queer nightly dream in which he was the timid little man Henry Stevens on that strange world called Earth.

He remembered now that Henry Stev-

DREAMER'S WORLDS

21

ens had promised a doctor that he would say aloud, "Thar isn't real—I, Khal Kan, am not real."

Khal Kan laughed. The idea of saying such a thing, of asserting that Thar and Jo-tan and everything else was not real, seemed idiotic.

"That timid little man I am in the dream each night—he thinks I would mouth such folly as that!" Khal Kan chuckled.

Golden Wings had awakened. Her slumbrous black eyes regarded him ques-tioningly.

"It's my own private joke, sweet," he told her. And he went on to tell her of the nightly dream he had had since childhood, of a queer world, called Earth in which he was another man. "It's the maddest world you can imagine, my pet—that dream-world. Men don't even wear swords, they don't know how to ride or fight like men, and they spend their lives plotting in stuffy rooms for a thing they call 'money'—bits of paper and metal.

"And the cream of the joke," Khal Kan laughed, "is that in my dream, I even doubt whether Thar is real. The dream-me believes that maybe this is the dream, that Jotan and Brusul and Zoor and even you are but phantom visions of my sleeping brain."

HE ROSE to his feet. "Enough of dreams and visions. Today "we ride to meet Egir and the Bunts. That is no dream!"

Ten thousand strong massed the fighting-men of Jotan later that morning, outside the walls of the city. Under the red sun their bronzed faces were sternly confident and eager for battle.

Kan Abul rode out through their ranks, with his captains behind him in full armor. Khal Kan was among them, and beside him rode Golden Wings. The desert princess had fiercely refused to be left behind.

Their helmets flashed in die red sun-

light, and the cheers of the troops were deafening as Kan Abul spoke to his captains.

"Egir's main force is already ten leagues north of Galoon," he told them. "There's talk of some new weapon which the Bunts have, with which they claim to be invincible. So we're going to take them by surprise.

■"I'll lead our main force of eight thousand archers and spearmen south along the coast road," the king continued. "My son, you will take our two thousand horsemen and ride over the first ridge of the Dragals, ■=■ then ride south ten leagues. We'll join battle with the Bunts down on the coastal plain, and you can come down from the Dragals and strike their flank. And the gods will be against us if we don't roll them up and destroy them as our forefathers did, generations ago."

Kan Abul led the troops down the coast -road, and as they marched along they roared out the old fighting-song of Jotan.

"The Bunts came up to Jotan, Long ago!"

Hours later, Khal Kan sat his horse amid a thin screen of brush high in the red easternmost ridge of the Dragals, leagues south of Jotan. Golden Wings sat her pony beside him, and their two thousand horsemen waited below the concealment of the ridge.

Down there below them, the red slopes dropped into a narrow plain between the mountains and the blue Zambrian. Far southward, a pall of black smoke marked the site of sacked Galoon. And from there, something like a glittering snake was crawling north along the coast.

"My Uncle Egir and his green devils," muttered Khal Kan. "Now where ate father and our footmen?"

"See—they come!" Golden Wings cried, pointing northward eagerly.

WEIRD TALES

IN THE north, a glittering serpent of almost equal size seemed crawling southward to meet the advancing Bunt columns. "Your desert eyes see well," declared Khal Kan. "Now we wait." ■ The two armies drew closer to each other. Horns were blaring now down in the Bunt columns, and the green bowmen were hastily forming up in double columns, a solid, blocky formation. More slowly, they advanced.

Trumpets roared in the north, where the footmen of Jotan marched steadily on. Faintly to the two on the ridge came the distant chorus.

"The Bunts fled back on the homeward l rack When blood did flow!"

"There is my uncle, damn him!" exclaimed Khal Kan, pointing.

He felt the old, bitter rage as he saw the stalwart, bright-helmed figure that rode with a group of Bunts at the head of the green men's army.

"He leads them to the battle," he muttered. "He never was a coward, whatever else he is. But today I will wipe out his menace to Jotan."

"They are fighting!" Golden Wings cried, with flaring eagerness.

Clouds of" arrows were whizzing between the two nearing armies, as Jotan archers and Bunt bowmen came within range.

Men began to drop in both armies— but in the Jotan army four fell for every stricken Bunt.

"Something's wrong!" Khal Kan cried. "Every man of ours who is even touched by an arrow is falling. I can't—"

"Poison!" hissed Golden Wings. "They are using poisoned arrows. It's a trick I've heard of the Nameless Men of the far north."

Khal Kan stared unbelievingly. "Even

the Bunts wouldn't use such hideous means! Yet my uncle is ruthless—"

Red rage misted his brain, and his voice was an unhuman roar as he turned and shouted to his tensely waiting horsemen.

"Our men are being slain by foul magic!" he yelled. "Down upon them— we strike for Jotan!"

It was as though he and Golden Wings were riding the forefront of a human avalanche as they charged down the steep slope to the battle.

They smashed home into the flank of the Bunts. The green men gave way in surprise and momentary terror. Kahl Kan's sword whipped like a lash of light among ugly green heads and thrusting spears. As always, in a fight, he moved by pure instinct rather than by conscious design.

Yet he kept Golden Wings a little behind him. The girl was fiercely wielding her light sword against those on the ground who sought to hamstring Khal Kan's horse with spear or sword. His riders were yelling shrilly.

HHHE crazy confusion of the battle took -*- on definite pattern. The Bunts had recoiled from the unexpected attack, but Egk was reforming them.

Khal Kan shouted and spurred to get at Egir. He could see his uncle's giant form, his cynical, powerful face under his helmet, and could hear his bull voice directing the reforming of the Bunt columns.

But he could not smash through the mad melee toward Egir. And now poisoned Bunt arrows were falling, dropping men from their saddles.

Brusul had reached him, was shouting to him. "Prince, your father is slain—one of those hellish arrows."

Khal Kan's heart went cold for a moment. He hardly heard Brusul's hoarse voice, shouting on.

"We can't face those poisoned shafts here in the open! Unless we fall back,

DREAMER'S WORLDS

23

they'M cut us down from a distance like grain in harvest-time!"

Khal Kan groaned. He saw the dilemma. They could not hope to smash the Bunt lines that Egir had reformed—and in a long battle the new poisoned arrows of the green men would take heavier and heavier toll of them.

The safety of Jotan was now a crushing weight on his shoulders. He was king now, and the dire responsibility of the position in this mad moment left him no time even for sorrow for his father. A battle lost here now meant that Jotan was defenseless before Egir's horde.

With a groan, he ordered a trumpeter to sound retreat

"Fall back toward Jotan!" he ordered. "March the footmen back on the double, Brusul—-we'll cover your withdrawal with the horsemen."

Through the long, hot hours of that afternoon, the bitter righting retreat surged back northward to Jotan. The Bunt columns followed closely, the green men howling with triumph.

Ever and again, Khal Kan and his riders charged back against the pursuing Bunts and smashed their front lines, making them recoil. Each time, empty saddles showed the toll of the poisoned shafts.

Sunset was flaring bloodily over the Dragals when the}' came back by that bitter way to the black towers of Jotan. Footsore, reeling with fatigue, Brusul's spearmen marched through the gate into the city.

One last charge back at the Bunts made Khal Kan with the horsemen. He rode back then with Golden Wings, who was swaying in her saddle. They two were the last of the riders to enter the city.

The great gates hastily ground shut, as sweating men labored in the dusk at the winches. Through the loopholes of the guard-towers, Khal Kan looked out and saw the Bunt hordes outside spreading to encircle the whole land side of Jotan.

"The}' have now four fighting-men to every one of ours," he muttered through his teeth. "We are in a trap called a city."

He was staggering, his face grimed and smeared with sweat and dust and blood. Golden Wings pressed his arm in complete faith.

"It was only the foul trick of the poisoned arrows that defeated tis!" she exclaimed. "But for that, we'd have rolled them into the sea."

"We have Egir to thank for that," rasped Khal Kan. "While that man lives, doom hangs like a thundercloud over Jotan."

He stepped to the window and sent his voice rolling out into the gathering darkness."

"Egir, will you settle this man to man, sword to sword? Speak!"

Back came a sardonic voice from the camp of the Bunts.

"I am not so simple, my dear nephew! Your city's a nut whose shell we'll soon crack and pick, so rest you."

Khal Kan set guards at every rod of the wall. Jotan's streets were dark under the two moons, for no torches had been lit this night. The sound of women's voices wailing a requiem for his dead father brought his numbed mind a sick sense of , loss.

No one else in Jotan spoke or broke the stillness. Awful and imminent peril crushed the city's folk. But from the darkness outside the walls came the sound of distant hammering as the Bunt hordes began making scaling-ladders for the morrow.

IjiROM a window of the palace, before he -*- collapsed in drugged sleep of exhaustion, Khal Kan saw the Bunt fires hemming in the whole landward side of the city in their crescent of flame. . . .

Henry Steven's wife had been worried about him all day. He had been

WEIRD TALES

acting queerly, she thought anxiously, ever since he had awakened that morning.

He had been pale and stricken and haggard since he had awakened. He had not gone to the office at all, a tiling unprecedented. And he had spent most of the day pacing to and fro in the little house, his haunted eyes not seeming to see her, his whole bearing one of intense excitement.

Henry was afraid—afraid of the dread climax to which things were rushing in the other world of Thar. He knew the awful peril in which Jotan now stood. Once those hordes of Bunts got over the wall, the city was doomed.

"I've got to qutt driving myself crazy about it," he told himself desperately that afternoon. "It's just a dream—Thar and Khal Kan must be only a dream."

But his feverish apprehension was not lessened by that thought. No- matter if Thar was only a dream, it was real to him!

TTE KNEW Jotan and its people, from -"•-^- the nightly dreams of his earliest

childhood. Every street of the black city he had known and loved, as Khal Kan. Even if it were only a dream, he couldn't let the old, lovely city and its people be overwhelmed by Egir and his green barbarians.

If Thar was the dream, and the city Jotan was taken and Khal Kan was slain— there would be an end to his precious dream-life, forever. Only the monotonous existence of Henry Stevens would stretch before him.

And if Thar happened to be the reality, then it was doubly vital that Khal Kan's people be saved from that menace.

"Yet what can I do?" Henry groaned inwardly. "What can Khal Kan do? The Bunts will surely break into the city—"

The poisoned arrows, new to the Jotani-ans, gave Egir's green warriors a terrific advantage. That, and their outnumbering hordes, would enable them to scale the

walls of Jotan and then the end would be at hand.

"Damn Egir for his deviltry in using those arrows!" Henry muttered. "I wish I could take a dozen machine-guns across. I'd show the cursed traitor."

It was a vain and idle wish, he knew. Nothing material could traverse the gulf between dream-world and real world, whichever was which. His own body, even —Henry Stevens' body—never crossed that gulf. AH he took into Thar each night were his memories of Henry Stevens' life on Earth during the day, and that seemed only a dream.

He could take memory across, though. And that thought gave pause to Henry. A faint gleam of hope appeared on his horizon. As Khal Kan, he would remember everything that he did or learned now, as Henry Stevens. Suppose that he—

"By Heaven!" Henry exclaimed excitedly. "There's a chance I could do it! A trick to overmatch Egir's poisoned arrows!"

His wife watched him puzzledly as he pored excitedly over certain volumes of their encyclopedia. She saw him hastily jot down notes, and then for a long time that evening he sat, moving his lips, apparently memorizing.

Henry was vibrant with excitement and hope. He, Henry Stevens of Earth, might be able to save Khal Kan's city for him!

"If Khal Kan will only do it!" he thought prayerfully. "If he won't just ignore it as dream—"

Waiting tensely for sleep that night, Henry repeated over and over to himself the simple formula he had gleaned from the encyclopedia.

"Khal Kan must try it!" he told himself desperately.

Sleep came slowly to him. And as he fell asleep, he knew that in his dream he would wake to what might be the last day of Jotan's existence. . . .

DREAMER'S WORLDS

Khal Kan awoke with that thought from his dream vibrating in his mind like an ominous tolling.

"The last day of Jotan!" he whispered. "By all the gods— no!"

Fiercely, the tall young prince rose and buckled on his sword. It was just dawn, and sea-mists shrouded all the city outside in gray fog.

Golden Wings still lay sleeping, Khal Kan heard a persistent hammering from out in the fog, as he went down to the lower level of the palace. Brusul, in full armor, came stalking up to him.

"All's quiet," reported the brawny captain. "The Bunts are still working away at their cursed scaling-ladders. When they are ready, they'll dear the walls of our men with their damned poisoned arrows, and then come over."

Khal Kan went out with him and inspected their defenses. As he supervised the placing of their fighting-men around the wall, and gave the white-faced people rough encouragement, something oppressed Khal Kan's mind. Something he should be doing for the defense of the city—

When he got back to the palace with Brusul, Golden Wings' slim, leather-clad figure came flying into his arms.

"I dreamed the Bunts were already in the city!" she cried. "And then I awoke and found you gone—"

Khal Kan, soothing her, suddenly stiffened. Her words had recalled that vague, forgotten something that had oppressed him.

"My dream!" he exclaimed. "I remember now—in the dream, on that other world, I learned how to make a weapon against the Bunts."

It had all come back to him now—the dream in which Henry Stevens had feverishly memorized a formula out of the science of that dream-world of Earth, to help him in his struggle against the Bunts.

For a moment, Khal Kan clutched at new hope. Then his eagerness faded. After all, that was only a dream. Henry Stevens and Earth and its science were only an insubstantial vision of his sleeping mind, and nothing that he learned in that could be of any value.

"I could wish you'd dreamed away the Bunts entirely," Brusul was saying dryly. "Unfortunately, they're still outside and it won't be many hours before they attack."

Khal Kan was not listening. His mind was revolving the simple formula that Henry Stevens had desperately memorized, in the dream.

"It wouldn't work," he thought. "It couldn't work, when there's no reality to all that—"

Yet he kept remembering Henry Stevens' desperate effort to help him. That timid, thin little man he was in his dream each night—that little man had prayed that Khal Kan would not ignore his help, would try the formula.

Khal Kan reached decision. "I'm going to try it—the thing I learned in the dream!" he told the others.

Brusul stared. "Are you wit-struck? Dreams won't help us now! How could a dream-weapon be of any use?"

"I'm not so sure now it was a dream," Khal Kan muttered. "Maybe this is the dream, after all. Oh, hell take all speculations—dream or reality, I'm going to try this thing."

He shot orders. "Bring all the charcoal you can find, all the sulphur from the street of the apothecaries, and all of the white crystals we use for drying fruits. Those crystals were called 'saltpeter' in the dream."

SCARED, wondering men brought the materials to the palace. There, Brusul and Zoor and Golden Wings watched mystifiedly as Khal Kan supervised their preparation.

WEIRD TALES

He remembered clearly the formula that Henry Stevens had memorized in the dream. He had the men pound and pulverize and mix, until a big mass of granular black powder was the result.

"Now bring small metal vases—enough to hold all this—and lampwicks and day," he ordered.

A captain came running, breathless. "The Bunts have finished their ladders and I think they're soon going to make their attack, sire!" he cried.

"And our leader lingers here, muddling in minerals!" cried Brusul gustily. "Khal Kan, forget this crazy dream and make ready for battle!"

T/" HAL KAN paid no attention. He was •*•** having the men stuff the small metal vases with the black powder, stopping their mouths with clay through which a fuselike wick protruded.

"Distribute these vases to all our men along the walls," he ordered. "Tell them, that when the Bunts place their ladders, they are to light the fuses and fling the vases down among the green warriors, at my command."

"Hell destroy all dreams!" raged Brusul. "What good will such a crazy plan do? Do you think dropping vases on the Bunts will stop them?"

"I don't know," Khal Kan muttered. "In the dream, I thought it would. The dream-me called the powder 'gunpowder' and the vases grenades.' And in the dream they seemed a more terrible weapon even than the poisoned arrows."

Yells from the walls and the warning blare of trumpets ripped across the sunlit city. A great cry swept through Jotan's streets.

"The Bunts are coming!"

"To the wall!" Khal Kan cried.

From the parapet atop the great wall, the rising sun revealed an ominous spectacle. From all around the landward side

of Jotan, the hordes of the Bunts were surging toward the city.

First came a line of green bowmen whose hissing, poisoned shafts were already rattling along the top of the wall. Jotanian warriors sank groaning as the swift poison sped into their blood. Khal Kan held his shield up, and swept Golden Wings behind him as they waited.

Behind the first line of bowmen came Bunts carrying long, rough wooden scaling-ladders. Behind these came the main masses of the stocky green men, armed with bows and short-swords, led by Egir himself.

The ladders came up against the wall, and the blood-chilling Bunt yell broke around the city as the green warriors swarmed catlike up them. Joranians who sought to push over the ladders were smitten by arrows.

"Over the wall and open the gates!" Egir's bull voice was yelling to his green men. "Let us into Jotan!"

The main horde of the Bunts was already surging toward the gates of the city, while their attackers on the ladders sought to win the wall.

"Now—light the fuses and drop the vases!" Khal Kan yelled along the parapet, through the melee.

Torches at readiness set the wicks alight. The seemingly harmless little metal vases were tossed over into the surging mass of the Bunts.

A series of ear-splitting crashes shook the air, like thunder. White smoke drifted away to show masses of the Bunts felled by the explosions.

"Gods!" cried Brusul appaliedly. "Your dream-weapon is thunder of heaven itself!"

"Magic!" yelled the Bunts, shrinking back aghast from their own dead, tumbling in panic off the ladders. "Flee, brothers!"

The fear-maddened green warriors surged back from the walls of Jotan, breaking in panic-stricken, disorganized masses.

DREAMER'S WORLDS

27

Egir's bull voice could be heard raging, trying to rally them, but in vain.

The men of Jotan who had lighted and flung the new weapons were as horrified as their victims. Khal Kan's yell aroused them.

"Horses, and after them!'' he cried. "Now is our chance to avenge yesterday!"

The gates ground open—and every horsemen left in jotan galloped out after Khal Kan and Golden Wings in pursuit of the routed, green men.

The Bunts made hardly any effort to turn and fight They were madly intent on putting as great a distance as possible between them and Jotan.

"It's Egir I'm after!'' Khal Kan cried to Brusul. "While he lives, no safety for Jotan!"

"See — there he rides!" cried Golden Wings' silvery voice.

Khal Kan yelled and put spur to his horse as he saw Egir and his Bunt captains riding full tilt toward the Dragals, in an effort to escape.

They rode right through the Seeing Bunts in pursuit of the traitor. They were overtaking him, when Egir turned and saw them coming. The Jotanian renegade uttered a yell, and he and his green captains turned.

" 'Ware arrows!" shouted Brusul, behind Khal Kan.

Khal Kan saw the Bunts loosing the vicious shafts, but he saw it only vaguely, for only Egir's sardonic face was clear to him as he charged.

Sword' out, he galloped toward his uncle. Something stung his arm, and he heard a scream from Golden Wings and knew an arrow had hit him.

"My dear nephew, you've two minutes to live!" panted JEgir, his eyes blazing hate and triumph as they met and their swords clashed. "You're a dead man now—"

Khal Kan felt a cold, deadly numbness creeping through his arm with incredible

rapidity. He summoned all his fa! ing strength to swing his sword up.

It left his guard open and Egir stabbed viciously as their horses wheeled. Then Khal Kan's nerveless arm brought his blade-down.

"This for my father, Egir!"

The sword shore the traitor's shoulder and neck half through. And a moment after Egir dropped from the saddle, Khal Kan felt his own numb body falling. He could not feel the impact with the ground.

His mind was darkening and everything was spinning around. It was as though he whirled in a black funnel, and was being sucked down into its depths, yet he could still hear voices of those bending over him.

"Khal Kan!" That was Golden Wings, he knew.

He tried to speak up to them out of the roaring darkness that was engulfing him.

"Jotan—safe now, with Egir gone. The kingship to Brusul. Golden Wings—"

He could not form more words. Khal Kan knew that he was dying. But he knew, at last, that Thar was not a dream, for even though his own life was passing, nothing around him was vanishing. But, his dark-enirfg brain wondered, if That had been real all the time—

But then, in a flash of light on the very verge of darkness, Khal Kan saw the truth that neither he nor the other had ever imagined. . . .