Fortunately, the commotion had not awakened Annette, and I did not wish to frighten her, now. I sat up for the rest of the night, thinking. I shall not say what I thought, nor shall I advance any theories. But when the estate of my uncle Alfred Fry is settled, Harris shall have the farm.

^m /iers in Wait

By MANLY WADE WELLMAN

Could it hare been thai Oliver Cromwell, ruthless Puritan dictator of England, used the Black Arts to win bis struggle with the Cavaliers?

Here lies our Sovereign Lord the King,

Whose word no mjji relies on, Who never said a foolish thing. Nor ever did a wise one.

— Proffered Epitaph on Charles 11

John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester

(1647-1680)

Yi

ES, Jack Wilmot wrote so concern* me, and rallied me, saying these

lines he would cut upon my monument; and now he is dead at thirty-three, while I live at fifty, none so merry a monarch as folks deem rac. Jack's verse makes me out a coxcomb, but he knew me not in

WEIRD TALES

my youth. He was but four, and sucking sugar-plums, when his father and I were fugitives after Worcester. Judge from this story, if he rhymes the truth of me.

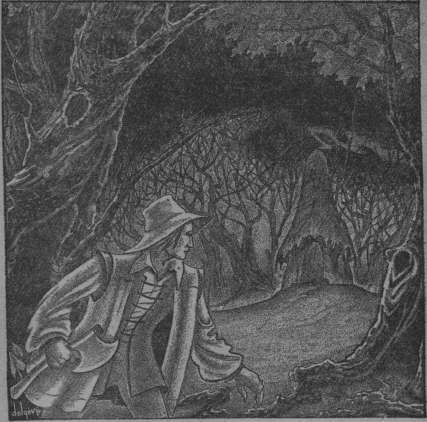

I think it was then, with the rain soaking my wretched borrowed clothes and the heavy tight plough-shoes rubbing my feet all to blisters, that I first knew consciously how misery may come to kings as to vagabonds. Egad, I was turned the second before I had well been the first. Trying to think of other things than my present sorry state among the dripping trees of Spring Coppice, I could but remember sorrier things still. Chiefly came to mind the Worcester fight, that had been rather a cutting down of my poor men like barley, and Cromwell's Ironside troopers the reapers; How could so much ill luck befall—Lauderdale's bold folly, that wasted our best men in a charge? The mazed silence of Leslie's Scots horse, the first of their blood I ever heard of before or since who refused battle? I remembered too, as a sick dream, how I charged with a few faithful at a troop of Parliamentarian horse said to be Cromwell's own guard; I had cut down a mailed rider with a pale face like the winter moon, and rode back dragging one of my own, wounded sore, across my saddle bow. He had died there, crying to me: "God save your most sacred Majesty!" And now I had need of God to save me.

"More things than Cromwell's wit and might went into this disaster," I told myself in the rain, nor knew how true I spoke.

After the battle, the retreat. Had it been only last night? Leslie's horsemen, who had refused to follow me toward Cromwell, had dogged me so close m fleeing him I was at pains to scatter and so avoid them. Late we had paused, my gentlemen and I, at a manor of White-Ladies. There we agreed to divide and flee in disguise. With trie help of two faithful yokels named Pen-derel I cut my long curls with a knife and crammed my big body into coarse gar-

ments—gray cloth breeches, a leathern doublet, a green jump-coat—while that my friends smeared my face and hands with chimney-soot. Then farewells, and I gave each gentleman a keep-sake—a ribbon, a buckle, a watch, and so forward. I remembered, too, my image in a mirror, and it was most unkingly—a towering, swarthy young man, ill-clad, ill-faced. One of the staunch Penderals bade me name myself, and I chose to be called Will Jones, a wandering woodcutter.

Will Jones! "Twas an easy name and comfortable. For the nonce I was happier with it than with Charles Stuart, England's king and son of that other Charles who had died by Cromwell's axe. I was heir to bitter sorrow and trouble and mystery, in my youth lost and hunted and friendless as any strong thief.

The rain was steady and weary. I tried to ask myself what I did here in Spring Coppice. It had been necessary to hide the day out, and travel by night; but whose thought was it to choose this dim, sorrowful wood? Richard Penderel had said that no rain fell elsewhere. Perhaps that was well, since Ironsides might forbear to seek me in such sorry bogs; but meanwhile I shivered and sighed, and wished myself a newt. The trees, what I could see, were broad oaks with some fir and larch, and the ground grew high with bracken reddened by September's first chill.

Musing thus, I heard a right ill sound —horses' hoofs. I threw myself half-down-ways among some larch scrub, peering out through the clumpy leaves. My right hand clutched the axe I carried as part of my masquerade. Beyond was a lane, and along it, one by one, rode enemy—a troop of Cromwell's horse, hard fellows and ready-seeming, with breasts and caps of iron. The)' stared right and left searchingly. The bright, bitter eyes of their officer seemed to strike through my hiding like a pike-point. I clutched my axe the tighter, and

THE LIERS IN WAIT

5?

swore on my soul that, if found, I would die fighting—a better death, after all, than my poor father's.

But they rode past, and out of sight. I sat up, and wiped muck from my long nose. "I am free yet," I told myself. "One day, please our Lord, I shall sit on the throne that is mine. Then shall I seek out these Ironsides and feed fat the gallows at Tyburn, the block at the Tower."

FOR I was young and cruel then, as now I am old and mellow. Religion perplexed and irked me. I could not understand nor like Cromwell's Praise-God men of war, whose faces were as sharp and merciless as, alas, their swords. "I'll give them texts to quote/' I vowed. "I have heard their canting war-cries. 'Smite and spare not!' They shall learn how it is to be smitten and spared not."

For the moment I felt as if vengeance were already mine, my house restored to power, my adversaries chained and delivered into my hand. Then I turned to cooler thoughts, and chiefly that I had best seek a hiding less handy to that trail through the trees.

The thought was like sudden memory, as if indeed I knew the Coppice and where best to go.

For I mind me how I rose from among the larches, turned on the heel of one pinching shoe, and struck through a belt of young spruce as though I were indeed a woodcutter seeking by familiar ways the door of mine own hut. So confidently did I stride that I blundered—or did I?— into a thorny vine that hung down from a long oak limb. It fastened upon my sleeve like urging fingers. "Nay, friend," I said to it, trying to be gay, "hold me not here in the wet," and I twitched away. That was one more matter about Spring Coppice that seemed strange and not overcanny—as also the rain, the gloom, my sudden desire to travel toward its heart. Yet, as you shall

see here, these things were strange only in their basic cause. But I forego the talc.

"So cometh Will Jones to his proper home," cjuoth I, axe on shoulder. Speaking thus merrily, I came upon another lane, but narrower than that on which the horsemen had ridden. This ran ankle-deep in mire, and I remember how the damp, soaking into my shoes, soothed those plaguey blisters. I followed the way for some score of paces, and meseemed that the rain was heaviest here, like a curtain before some hidden thing. Then I came into a cleared space, with no trees nor bush, nor even grass upon the bald earth. In its center, wreathed with rainy mists, a house.

I paused, just within shelter of the leaves. "What," I wondered, "has my new magic of being a woodcutter conjured up a woodcutter's shelter?"

But this house was no honest workman's place, that much I saw with but half an eye. Conjured up it might well have been, and most foully. I gazed at it without savor, and saw that it was not large, but lean and high-looking by reason of the steep pitch of its roof. That roof's thatch was so wet and foul that it seemed all of one drooping substance, like the cap of a dark toadstool. The walls, too, were damp, being of clay daub spread upon a framework of wattles. It had one door, and that a mighty thick heavy one, of a single dark plank that hung upon heavy rusty hinges. One window it had, too, through which gleamed some sort of light; but instead of glass the window was filled with something like thin-scraped rawhide, so that light could come through, but not the shape of things within. And so I knew not what was in that house, nor at the time had I any conscious lust to find out.

I say, no conscious lust. For it was unconsciously that I drifted idly forth from the screen of wet leaves, gained and moved along a little hard-packed path between bracken-clumps. That path led to the

WEIRD TALES

door, and I found myself standing before it; while through the skinned-over window, inches away, I heard noises.

Noises I call them, for at first I could not think they were voices. Several soft hummings or puttings came to my ears, from what source I knew not. Finally, though, actual words, high and raspy:

"We who keep the commandment love the law! Moloch, Lucifer, Bal-Tigh-Mor, Anector, Somiator, sleep ye not! Compel ye that the man approach!"

It had the sound of a prayer, and yet I recognized but one of the names called— Lucifer. Tutors, parsons, my late unhappy allies die Scots Covenentors, had used the name oft and fearfully. Prayer within that ugly lean house went up—or down, belike—to the fallen Son of the Morning. I stood against the door, pondering. My grandsire, King James, had believed and feared such folks' pretense. My father, who was King Charles before me, was pleased to doubt and be merciful, pardoning many accused witches and sorcerers. As for me, my short life had held scant leisure to decide such a matter. While I waited in the fine misty rain on the threshold, the high voice spoke again:

"Drive him to us! Drive him to us! Drive him to us!"

Silence within, and you may be sure silence without. A new voice, younger and thinner, made itself heard: "Naught comes to us."

"Respect the promises of our masters," replied the first. "What says the book?''

And yet a new voice, this time soft and a woman's: "Let the door be opened and the wayfarer be plucked in."

T SWEAR that I had not the least impulse -^ to retreat, even to step aside. 'Twas as if all my life depended on knowing more. As I stood, ears aprick like any cat's, the door creaked inward by three inches. An arm in a dark sleeve shot out, and fingers

as lean and clutching as thorn-twigs fastened on the front of my jump-coat.

"I have him safe!" rasped the high voice that had prayed. A moment later I was drawn inside, before I could ask the reason.

There was one room to the house, and it stank of burning weeds. There were no chairs or other furniture, and no fireplace; but in the center of the tamped-clay floor burned an open fire, whose rank smoke climbed to a hole at the roof's peak. Around this fire was drawn a circle in white chalk, and around the circle a star in red. Close outside the star were the three whose voices 1 had r .-

Mine eyes lighted first on she who held the book—young she was and dainty. She sat on the floor, her feet drawn under her full skirt of black stuff. Above a white collar of Dutch style, her face was round and at the same time fine and fair, with a short red mouth and blue eyes like the clean sea.

Her hair, under a white cap. was as yellow as corn. She held in her slim white hands a thick book, whose cover looked to be grown over with dark hair, like the hide of a Galloway bull.

Her eyes held mine for two trices, then I looked beyond her to another seated person. He was small enough to be a child, but the narrow bright eyes in his thin face were older than the oldest I had seen, and the hands clasped around his bony knees were rough and sinewy, with large sore-seeming joints. His hair was scanty, and eke his eyebrows. His neck showed swollen painfully.

It is odd that my last look was for him who had drawn me in. He was tall, almost as myself, and grizzled hair fell on the shoulders of his velvet doublet. One claw still clapped hold of me and his face, ' a foot from mine, was as dark and bloodless as earth. Its lips were loose, its quivering nose broken. The eyes, cold and

T7

wide as a frog's, were as steady as gun-muzzles,

He kicked the door shut, and let me go. "Name yourself," he rasped at me. "If you be not he whom we seek—"

"I am Will Jones, a poor woodcutter," I told him.

"Mmmm," murmured the wench with the book. "Belike the youngest of seven sons—-sent forth by a cruel step-dame to seek fortune in the world. So runs the fairy tale, and we want none such. Your true name, sirrah."

I told her roundly that she was insolent, but she only smiled. And I never saw a fairer than she, not in all the courts of Europe—not even sweet Nell Gwyn. After many years I can see her eyes, a little slanting and a little hungry. Even when I was so young, women feared me, but this one did not.

"His word shall not need," spoke the thin young-old fellow by the fire. "Am I not here to make him prove himself?" He lifted his face so that the fire brightened it, and I saw hot red blotches thereon.

'True," agreed the grizzled man. "Sirrah, whether you be Will Jones the woodman or Charles Stuart the king, have you no mercy on poor Diccon yonder? If 'twould ease his ail, would you not touch him?"

That was a sneer, but I looked closer at the thin fellow called Diccon, and made sure that he was indeed sick and sorry. His face grew full of hope, turning up to me. I stepped closer to him.

"Why, with all my heart, if 'twill serve," I replied.

'"Ware the star and circle, step not within the star and circle," cautioned the wench, but I came not near those marks. Standing beside and above Diccon, I felt his brow, and felt that it was fevered. "A hot humor is in your blood, friend," I said to him, and touched the swelling on his neck.

But had there been a swelling there? I touched it, but 'twas suddenly gone, like a furtive mouse under my finger. Diccon's neck looked lean and healthy. His face smiled, and from it had fled the red blotches. He gave a cry and sprang to his feet.

" 'Tis past, 'tis past!" he howled. "I am whole again!"

But the eyes of his comrades were for me.

"Only a king could have done so," quote the older man. "Young sir, I do take you truly for Charles Stuart. At your touch Diccon was healed of the king's evil."

I folded my arms, as if I must keej-my hands from doing more strangeness. 1 had heard, too, of that old legend of the Stuarts, without deeming myself concerned. Yet, here it had befallen. Diccon had suffered from the king's evil, which learned doctors call scrofula. My touch had driven it from his thin body. He danced and quivered with the joy of health. But his fellows looked at me as though I had betrayed myself by sin.

"It is indeed the king," said the girl, also rising to her feet.

"No," I made shift to say. "I am but poor Will Jones," and I wondered where I had let fall my axe. "Will Jones, a woodcutter."

"Yours to command, Will Jones," mocked the grizzled man. "My name is Valois Pembru, erst a schoolmaster. My daughter Regan," and he flourished one of his talons at the wench. "Diccon, our kinsman and servitor, you know already, well enough to heal him. For our profession, we are—are—"

HE SEEMED to have said too much, and his daughter came to his rescue. "We are liers in wait," she said.

"True, liers in wait," repeated Pembru, glad of the words. "Quiet we bide our time, against what good things comes our

WEIRD TALES

way. As yourself, Will Jones. Would you sit in soouh upon the throne of England? For that question we brought you hither."

I did not like his lofty air, like a man cozening puppies. "I came myself, of mine own good will," I told him. "It rains outside."

"True," muttered Diccon, his eyes on me. "All over Spring Coppice falls the rain, and not elsewhere. Not one, but eight charms in yonder book can bring rain— 'twas to drive your honor to us, that you might heal—"

"Silence," barked Valois Pembru at him. And to me: "Young sir, we read and prayed and burnt," and he glanced at the dark-orange flames of the fire. "In that way we guided your footsteps to the Coppice, and the rain then made you see this shelter. 'Twas all planned, even before Noll Cromwell scotched you at Worcester—"

"Worcester!" T roared at him so loudly that he stepped back. "What know you of Worcester fight?"

He recovered, and said in his erst lofty fashion: "Worcester was our doing, too. We gave the victory to Noll Cromwell. At a price—from the book."

He pointed to the hairy tome in the hands of Regan, his daughter. "The flames showed us your pictured hosts and his, and what befell. You might have stood against him, even prevailed, but for the horsemen who would not right."

I remembered that bitter amazement over how Leslie's Scots had bode like statues. "You dare say you wrought that?"

Pembru nodded at Mistress Regan, who turned pages. "I will read it without the words of power," quoth she. "Thus: Tn meekness I begin my work. Stop rider! Stop footman! Three black flowers bloom, and under them ye must stand still as long as I will, not through me but through the name of—"

She broke off, staring at me with her

slant blue eyes. I remembered all the tales of my grandfather James, who had fought and written against witchcraft. "Well, then, you have given the victory to Cromwell. You will give me to him also?"

Two of the three laughed—Diccon was still too mazed with his new health—and Pembru shook his grizzled head. "Not so, woodcutter. Cromwell asked not the favor from us—'twas one of his men, who paid well. We swore that old Noll should prevail from the moment of battle. But," and his eyes were like gimlets in mine, "we swore by the oaths set us—the names Cromwell's men worship, not the names we worship. We will keep the promise as long as we will, and no longer."

"When it pleases us we make," contributed Regan. "When it pleases us we break."

Now 'tis true that Cromwell perished on third September, 1658, seven year to the day from Worcester fight. But I half-believed Pembru even as he spoke, and so would you have done. He seemed to be what he called himself—a lier in wait, a bider for prey, myself or others. The rank smoke of the fire made my head throb, and I was weary of being played with. "Let be," I said. "I am no mouse to be played with, you gibbed cats. What is your will?"

"An," sighed Pembru silkily, as though he had waited for me to ask, "what but that our sovereign should find his fortune again, scatter the Ironsides of the Parliament in another battle and come to his throne at Whitehall?"

"It can be done," "Regan assured me. "Shall I find the words in the book, that when spoken will gather and make resolute your scattered, running friends?"

I put up a hand. "Read nothing. Tell me rather what you would gain thereby, since you seem to be governed by gains alone."

"Charles Second shall reign," breathed Pembru. "Wisely and well, with thoughtful distinction. He will thank his good

THE LIERS IN WAIT

59

councillor the Earl—no, the Duke—of Pembru. He will be served well by Sir Diccon, his squire of the body."

"Served well, I swear," promised Diccon, with no mockery to his words.

"And," cooed Regan, "are there not ladies of the court? Will it not be said that Lady Regan Pembru is fairest and—most pleasing to the king's grace?"

Then they were all silent, waiting for me to speak. God pardon me my many sins! But among them has not been silence when words are needed. I laughed fiercely.

"You are three saucy lackeys, ripe to be flogged at the cart's tail," I told them. "By tricks you learned of my ill fortune, arid seek to fatten thereon." I turned toward the door. "I sicken in your company, and I leave. Let him hinder me who dare."

"Diccon!" called Pembru, and moved as if to cross my path. Diccon obediently ranged alongside. I stepped up to them.

"If you dread me not as your ruler, dread me as a big man and a strong," I said. "Step from my way, or I will smash your shallow skulls together."

Then it was Regan, standing across the door.

"Would the king strike a woman?" she challenged. "Wait for two words to be spoken. Suppose we have the powers we claim?"

"Your talk is empty, without proof," I replied. "No. mistress, bar me not. I am going."

"Proof you shall have," she assured me hastily. "Diccon, scir the fire."

HE DID so. Watching, I saw that in sooth he was but a lad—his disease, now banished by my touch, had put a false seeming of age upon him. Flames leaped up, and upon them Pembru cast a handful of herbs whose sort I did not know. The color of the fire changed as I gazed, white, then rosy red, then blue, then again white. The wench Regan was

babbling words from the hair-bound book; but, though I had. learned most tongues in my youth, I could not guess what language she read.

"Ah, now," said Pembru. "Look, your gracious majesty. Have you wondered of your beaten followers?"

In the deep of the fire, like a picture that forebore burning and moved with life, I saw tiny figures—horsemen in a huddled knot riding in dejected wise. Though it was as if they rode at a distance, I fancied that I recognized young Straike— a cornet of Leslie's. I scowled, and the vision vanished.

"You have prepared puppets, or a shadow-show," I accused. "I am no country hodge to be tricked thus."

"Ask of the fire what it will mirror to you," bade Pembru, and I looked on him with disdain.

"What of Noll Cromwell?" I demanded, and on the trice he was there. I had seen the fellow once, years agone. He looked more gray and bloated and fierce now, but it was he—Cromwell, the king rebel, in back and breast of steel with buff sleeves. He stood with wide-planted feet and a hand on his sword. I took it that he was on a porch or platform, about to speak to a throng dimly seen.

"You knew that I would call for Cromwell," I charged Pembru, and the second image, too, winked out.

He smiled, as if my stubbornness was what he loved best on earth. "Who else, then? Name one I cannot have prepared for."

"Wilmot," I said, and quick anon I saw him. Poor nobleman! He was not young enough to tramp the byways in masquerade, like me. He rode a horse, and that a sorry one, with his pale face cast down. He mourned, perhaps for me. I feit like smiling at this image of my friend, and like weeping, too.

"Others? Your gentlemen?" suggested

WEIRD TALES

Pembru, and witliuut my naming they sprang into view one after another, each in a breath's space. Their faces flashed among the shreds of flame—Buckingham, elegant and furtive; Lauderdale, drinking from a leather cup; Colonel Carlis, whom we called "Careless," though he was never that; the brothers Penderel, by a fireside with an old dame who may have been their mother; suddenly, as a finish to the show, Cromwell again, seen near with a bible in his hand.

The fire died, like a blown candle. The room was dim and gray, with a whisp of ;rnoke across the hide-spread window.

"Well, sire? You believe?" said Pembru. He smiled now, and I saw teeth as lean and white as a hunting dog's.

"Faith, only a fool would refuse to believe," I said in all honesty.

He stepped near. "Then you accept us?" he questioned hoarsely. On my other hand tiptoed the fair lass Regan.

"Charles!" she whispered. "Charles, my comely king!" and pushed herself close against me, like a cat seeking caresses.

"Your choice is wise," Pembroke said on. "Spells bemused and scattered your army—spells will bring it back afresh. You shall triumph, and salt England with the bones of the rebels. Noll Cromwell shall swing from a gallows, that all like rogues may take warning. And you, brought

by our powers to your proper throne "

"Hold," I said, and they looked upon me silently.

"I said only that I believe in your sorcery," I told them, "but I will have none of it."

You would have thought those words plain and round enough. But my three neighbors in that ill house stared mutely, as if I spoke strangely and foolishly. Finally: "Oh, brave and gay! Let me perish else!" quoth Pembru, and laughed.

My temper went, and with it my be-musement. "Perish you shall, dog, for

your saucy ways," I promised. "What, you stare and grin? Am I your sovereign lord, or am I a penny show? I have humored you too long. Good-bye."

I made a step to leave, and Pembru slid across my path. His daughter Regan was opening the book and reciting hurriedly, but I minded her not a penny. Instead, I smote Pembru with my fist, hard and fair in the middle of his mocking face. And down he went, full-sprawl, rosy blood fountiining over mouth and chin.

"Cross me again," quoth I, 'and I'll drive you into your native dirt like a tether-peg." With that, I stepped across his body where it quivered like a wounded snake, and put forth my hand to open the door.

There was no door. Not anywhere in the room.

I turned back, the while Regan finished reading and closed the book upon her slim finger.

"You see, Charles Stuart," she smiled, "you must bide here in despite of yourself."

"Sir, sir," pleaded Diccon, half-crouching like a cricket, "will you not mend your opinion of us?"

"I will mend naught," I said, "save the lack of a door." And I gave the wall a kick that shook the stout wattlings and brought down flakes of clay. My blistered foot quivered with pain, but another kick made some of the poles spring from their fastenings. In a moment I would open a way outward, would go forth.

REGAN shouted new words from the book. I remember a few, like uncouth names—Sator, Arepos, Janna. I have heard since that these are powerful matters with the Gnostics. In the midst of her outcry, I thought smoke drifted before me —smoke |hat stank like dead flesh, and thickened into globes and curves, as if it

THE LIERS IN WAIT

61

would make a form. Two long streamers of k drifted out like snakes, to touch or seize me, I gave baric, and Regan stood at my side.

"Would you choose those arms," asked she. "and not these?" She held out her own, fair and round and white. "Charles, I charmed away the door. I charmed that spirit to hold you. I will still do you good in despite of your will-—you shall reign in England, and I—and I "

Weariness was drowning me. I felt like a child, drowsy and drooping. "And you?" I said.

"You shall tell me," she whispered. "Charles."

She shimmered in my sight, and bells sang as if to signal her victory. I swear it was not I who spoke then stupidly—cun-sult Jack Wilmot's doggerel to see if I am wont to be stupid. But the voice came from my mouth: "I shall be king in Whitehall."

She prompted me softly: "I shall be duchess, and next friend—-"

"Duchess and next friend," I repeated.

"Of the king's self!" she finished, and I opened my mouth to say that, too. Valois Pembru, recovering from my buffet, sat up and listened.

But

"STOP!" roared Diccon.

WE all looked—Regan and I and Valois Pembru. Diccon rose from where he crouched. In liis slim, strong hands was the foul hairy book that Regan had laid aside. His finger marked a place on the open page.

"The spells are mine, and I undo what they have wrought!" he thundered in his great new voice. "Stop and silence! Look upon me, ye sorcerers and arch-sorcerers! You who attack Charles Stuart, let that witchcraft recede from him into your marrow and bone, in this instant and hour—"

He read more, but I could not hear for

the horrid cries of Pembru and his daughter.

The rawhide at the window split, like a drum-head made too hot. And cold air rushed in. The fire that had vanished leaped up, its flames bright red and natural now. Its flames scaled the roof-peak, caught there. Smoke, rank and foul, crammed the place. Through it rang more screams, and I heard Regan, pantingly:

"Hands—from—my—throat !"

Whatever had seized her, it was not Diccon, for he was at my side, hand on my sleeve.

"Come, sire! This way!"

Whither the door had gone, thither it now came back. Wc found it open before us, scrambled through and into the open.

THE hut burnt behind us like a hayrick, and I heard no more cries therefrom. "Pembru!" I cried. "Regan! Are they slain?"

"Slain or no, it does, not signify," replied Dkcon. "Their ill magic retorted upon them. They are gone with it from earth—forever." He hurled the hairy book into die midst of the flame. "Now, away."

We left the clearing, and walked the lane. There was no more rainfall, no more mist. Warm light came through the leaves as through clear green water.

"Sire," said Diccon, "I part from you. God bless your kind and gracious majesty! Bring you safe to your own place, and your people to their proper senses."

He caught my hand and kissed it, and would have knelt. But I held him on his feet.

"Dkcon," I said, "I took you for one of those liers in wait. But you have been my friend this day, and I stand in your debt as long as I live."

"No, sire, no. Your touch drove frpm me the pain of the king's evil, which had

WEIRD TALES

smitten mc since childhood, and which those God-forgotten could not heal with all their charms. And, too, you refused witch-help against Cromwell."

I met his round, true eye. "Sooth to say, Cromwell and I make war on each other," I replied, "but "

"But 'tis human war," he said for me. "Each in his way hates hell. 'Twas bravely done, sire. Remember that Cromwell's course is run in seven years. Be content until then. Now—Godspeed!"

He turned suddenly and made off amid the leafage. I walked on alone, toward where the brothers Penderel would rejoin me with news of where next we would seek safety.

MANY things churned in my silly head, things that have not sorted themselves in all the years since; but this came to the top of the churn like fair butter.

The war in England was sad and sorry and bloody, as all wars. Each party called the other God-forsaken, devilish. Each was

wrong. We were but human folk, doing what we thought well, and doing it ill. Worse than any human foe was sorcery and appeal to the devil's host.

I promise myself then, and have not since departed from it, that when I ruled, no honest religion would be driven out. All and any such, I said in my heart, was so good that it bettered the worship of evil. Beyond that, I wished only for peace and security, and the chance to take off my blistering shoes.

"Lord," I prayed, "if thou art pleased to restore me to the throne of my ancestors, grant me a heart constant in the exercise and protection of true worship. Never :ek the oppression of those who, out of tenderness of their consciences, are not free to conform to outward and indifferent ceremonies."

And now judge between me and Jack Wilmot, Earl of Rochester. There is at least one promise I have kept, and at least one wise deed I have done. Put that on my grave.

Some unseen force hurled Sis body squarely into the core o£ this purpls flame!

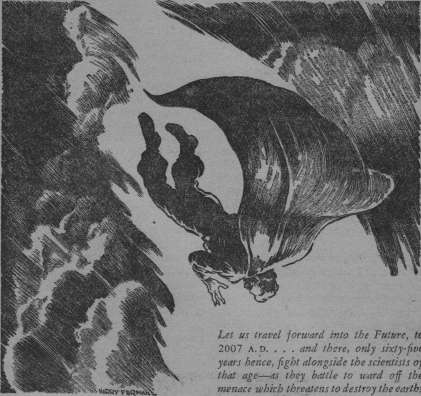

Let us travel forward into the Future, to 2007 a. d. . . . and there, only sixty-jive years hence, fight alongside the scientists of that age — as they battle to ward off the menace which threatens to destroy the earth!

G

ore of the Purple Flame

By ROBERT H. LETTERED

WHEN the young scientist Aaron Carruthers finished computing the intricate problem before him on his desk, he closed his eyes as if to visualize the chaos these symbols denoted.

Thin beads of sweat formed on his high, intelligent forehead. Three times had he re-checked the problem to make certain there had been no error. He had even sent word to a colleague, George Vignot,

to come to the laboratory and work out the problem in his own way just to make certain that there had been no mistake.

In a few minutes the big, bearded chemist, Vignot, would arrive. No chance that both would make the same mistake. And if Vignot's conclusions matched his own— well, ihc- astounding and fearsome news would have to be sent out to the world on the Continental Television News panels.

WEIRD TALES

Carruthers wiped his forehead. It was entirely possible that he was wrong. After all, he wasn't infallible. He tried to remember errors in calculations he had made in the past. But they were surprisingly few and were errors of haste rather than method. And there was no consolation in them.

Tiredness was upon him. He allowed his body to slump forward until his damp forehead rested in the crook of his arm. But he couldn't thrust the horror of the future from his mind. And while he tried to forget momentarily what he, alone in all the world knew, time kept ticking off its inexorable seconds and minutes. There was no stopping its remorseless march onward.

The year of time was 2007 as reckoned by the earth's new calendar, and was still the same world with its familiar continents and oceans as recorded by the historians of the twentieth century.

There had been wars, pestilence, famines and destruction undreamed of in the red decades following the rise of the dictator nations. Empires had spread their tentacles over most of the earth's surface —enslaving humans with their mephitic, bestial ideologies.

Then the people, as if inspired and guided by some soul-inspiring force outside their enslaved bodies, had risen in rebellion all over the world, thrown off their shackles, and annihilated their masters.

Scientifically and mechanically, the world had never stood still. There seemed to be no end to the inventive genius of mankind. But man, himself, had not changed—only the structures that housed him, and the mechanical marvels that surrounded him. He was still r-ubject to greed, poverty and fear of the unknown. In the world's largest city, New York, the month of Venus brought intolerable heat that drove people deep underground to ventilated caverns constructed when

Venus had been known as the month of July. Those who were not in the caverns, or not working at daily tasks, were garnered before the Continental Television News panels where they watched rathef than heard world news. Aside from the seasonal heat, there was nothing to mar the serenity of their daily lives.

Around them, as they stood watching the news flash across the panel from all parts of the globe, towered massive buildings. The tallest of these was the one where Aaron Carruthers' connecting laboratories covered the top floor of a hundred-story structure.

Looking from the quartz glass windows of these laboratories, one could see the steel control towers of New York's majestic transportation system—the four-speed sidewalk bands that extended north, south, east and west.

Subway and elevated trains no longer existed. Taxis and privately owned vehicles had been banished to the great open spaces known as the outlands.

This efficient transportation system, of escalator type, was high above the city streets, and extended north to Pcckskill and west across the Hudson River into a teeming industrial center that had once been known as New Jersey.

The first band from the station platform moved cjuite slowly. The second, somewhat faster. By stepping from the slower to the faster-moving bands, passengers could easily control the speed they wished to travel.

There was little or no noise in this sprawling metropolitan area except the droning reverberations of turbines deep underground — turbines which supplied light, power and heat to all businesses, all families, rich and poor alike.

Even to this lonely, serious-faced young scientist there came moments of reflection when he marveled at the changes that had taken place during his own lifetime. But

CORE OF THE PURPLE FLAME

6?

he wasn't thinking about them now. They had been crowded from his mind by gloomy forebodings of an insecure future. This precious, yet terrible knowledge weighed heavily, on his shoulders. He clenched his jaw and straightened to an upright position.

The red eyes of a golden Buddha on his desk glowed warningly. Someone was coming down the corridor to the entrance of his private laboratory.

Soundlessly the door opened. Through the opening came his friend and laboratory assistant, Karl Danzig. "Vignot's here," he stated, 'and crusty as usual."

CARRUTHERS nodded. He liked George Vignot in spite of the bearded chemist's sarcastic, blustering ways. "Show him into the west laboratory where our Time Projector— No. Wait a minute. Vignot's not yet ready for that experiment. Show him instead into the Thermo-cell laboratory. We'll work on our problem there."

The eyes of Karl Danzig held worried glints. ■

He hesitated a moment then said: "You—you aren't going to test out the new Time Projector Machine—?"

"It all depends," shrugged Carruthers, "on whether certain computations I have made are correct in assumption and ultimate result. Vignot's undoubtedly the foremost mathematician in the east. And I want him to re-check my calculations for possible error. If he arrives at the same answer as I have, we'll make the experiment -— provided he is willing and not afraid."

Still, Dan2ig did not leave the room. "In some ways," he went on, "I wish you'd abandon the experiment, Aaron. It's not that I'm disloyal, but it seems to me that you're going to get entangled into something that—that the universal creator doesn't want mankind to know. Some-

how, it doesn't seem right for man to probe into the mystery of what has not yet happened."

Carruthers placed a hand on his friend's shoulder. "I'm not questioning your loyalty, Karl, when you oppose the experiment I've got to go through with. But I know you'll stand by till the end. Perhaps I'm asking for death in trying to do some-think that transcends the physical impossibility of tampering with the element of time.

"Still, being the way I am, there seems no other course open—for me at least. So don't have any doubts. We've been mixed up in strange and fantastic experiences before, and have somehow survived. Let's keep the thought in mind that we'll survive this one."

Danzig nodded. "I understand all that, Aaron. But you've never gone through anything like the experiment you've planned with the Time Projector Machine. You still don't know what effect it will have on your physical body."

"I've tried it on mice and they came back alive."

"Mice aren't human beings. It scares me, Aaron. Things that have happened in the past are history, and they're static in most ways. Things that are happening in the present are understandable and real. They are things you and I can get a grip on. I can touch my skin, my hair and fingernails, and feel them. They are the result ol growth that extends into the past, itiey are also the result of growth that is taking place this very second."

"That's quite true, Karl. The sum of our knowledge is based on what is happening now, and what has taken place in the past. That being true, would not our knowledge be astoundingly increased in the revealing awareness of what is going to happen in—say a year from now, or a decade of years for that matter? Could we not arrange to meet misfortune and disas-

WEIRD TALKS

ter better if we knew what was to take place in the future?"

"You're getting into the realm of predestination, Aaron. And that is dangerous ground for man to invade. Suppose fate has willed that I am to die at eleven o'clock at night a year from today from coming in contact with fifty-thousand volts of electricity in this laboratory. Could you, by your foreknowledge of events that are yet to happen, cheat fate by having the current turned off so that I couldn't possibly be electrocuted?''

"I don't know, Karl, any more than you do." The shadow of some inner disturbance crossed his serious young face. When he spoke again his voice was low and vibrant. "But the scientific urge to find the answer to your question and others of my own propounding is greater than my emotional will to resist that urge. I've got to find out, Karl. My mind won't rest, nor my body either, until the answer to the riddle comes to me out of the impalpable element of a time period that has not yet taken place. Go get Vignot now, and bring him to the Thermo-cell laboratory. And I'll want you with us, Karl, for reasons you'll discover for yourself."

Without another word he turned and walked down a tile corridor to a white, gleaming laboratory. A few minutes later Danzig, with George Vignot close behind him, entered the room.

GEORGE VIGNOT spread his feet wide and puffed out both checks. "So!" His voice had the booming quality of a deep organ note. "It isn't enough that I should be plagued by inconsequential classroom experiments I have performed a thousand—yes, a million times. No. I must fritter away my precious moments with arithmetic, with figures which you seemed to have forgotten—"

"Wait a minute, Vignot—"

"Ha. Wait? Always I'm waiting.

Where is this Time Proj'ector? Speak up, for I have no time to waste on trivialities. Certainly it isn't in this room. It wouldn't be. You'd keep it hidden. I don't want to see it. I don't want anything to do with it. The last experience I had with your Neutronium exploration apparatus nearly drove me insane. I damned near starved to death, too. No. Count me out of any future experiments dealing with the unknown. I'll stick to my moronic classroom lectures—"

"I suppose," Carruthers broke in, "that I could easily persuade the noted bio-chemist, Haley, to assist me, or Professor Grange the metallurgist whose experiments and findings have lately startled the world. Not being concerned with petty classroom sessions, they'd undoubtedly—"

"Bah! Haley's a doddering fool. And Grange is afraid of his own shadow. Petty classroom sessions, eh? You brought that up, Aaron, just to goad me on into doing something I don't want—"

Carruthers shook his head. "I wouldn't urge you to do anything you don't want to djo, or have your heart set on doing. Go back to your classroom. I'll find someone else."

Vignot's big body shook with gusty laughter. "Oh ho! I should go now after I'm already here. You should get rid of me like I'm an incompetent scullion who keeps dropping beakers and test tubes. I'm not so good as Haley or Grange. So now. What is that problem in arithmetic?"

"The arithmetic will come in a few minutes." He pointed to a marble-topped table. "First, I want you to check the readings on the tape from the Thermo-cell unit recordings."

"Hummm!" grunted Vignot, crossing the room to the table and bending over the intricate machine which indicated and traced the pattern of any electrical or metallic disturbances in the outer reaches of the sky.

CORE OF THE PURPLE FLAME

67

Since he was familiar with the unit, he had no difficulty. "Solar disturbances as usual,'' he muttered, "but no radio signals or undiscovered mass formations—wait a second. Maybe I'm wrong. The indicator won't remain on the 2ero line. Ah! There is a disturbance caused by the presence of matter. It's center—let me calculate roughly—just as I thought—about seventeen degrees to the left of the planet Neptune."

"Well?" Carruthers' voice had a touch of impatience.

Vignot peered at a map of star constellations on the nearest wall. "You tell me, Aaron. There's nothing but bleak emptiness in that part of the sky. It's a place where time seems to stand still, where distances from one body to another are fixed at millions of miles. It's a vast immensity where there is no light, no heat, no sound, and nothing more substantial than occasional streamers of dark, gaseous clouds/'

He turned to Carruthers and spread his hands, palms upward. "The disturbance is caused by a comet. Any astronomer could have told you that much. It's that simple."

"Not quite," said Carruthers. "I thought of comets. On the table beside the Thermo-cell unit you'll find charts. The top one was made in 1967, and based on figures and negatives furnished me by the Palomar Observatory. Plotted on this chart are the paths of various wanderers of the sky—meteors, asteroids and comets. None of them are to be found in the sky area on which the unit's detector beam is centered.

"On the second chart you'll find the periodic comets and their paths across the heavens. Biela's comet, first observed in 1772, returns every seven years. It isn't due again for five years. Rule that one out."

Vignot shrugged. "Go on," he urged.

"Following it is one discovered by Encke. Its period of visibility at a fixed point in the sky occurs every three years.

Then Halley's comet comes along with a period of seventy-six years, followed by Donati's which appears at intervals several thousand years apart. None are due this year—or now."

George Vignot tugged thoughtfully at his beard. "I see," he nodded. "But all this talk about comets must mean something. What?"

Carruthers watched both men seat themselves in comfortable chairs but made no motion to follow their example. Instead he began to pace the floor. "I didn't say anything about comets. You brought them into our talk yourself. The thing that is causing the disturbance on the sensitive plates of the Thermo-cell unit might be a planet or a star, or a globe like our own inhabitated with human beings.

"Or it may be nothing more than a sphere of black gas with a metallic core because it isn't yet visible. And it's out there in that bleak emptiness as, you call it, beyond the gravitational pull of Neptune. It's still impossible to correctly determine its size or structure. But if the Thermo-cell unit is accurate to within one tenth of a degree, that invisible body is headed toward our earth at a tremendous speed which will accelerate to an even greater velocity as its expanding gases drive it onward. And unless it meets with some other mass in the sky, it should be hurling itself in a mighty cataclysm against our earth—"

"/"< OOD Lord," breathed Vignot. ^-J "When does all this take place?"

"That's the problem in arithmetic you so caustically referred to. We have its location in the sky. We have its speed—"

"Speed?" Vignot looked doubtful.

"That can be determined by examining the strength of the first disturbance signals on the cell plate recording tape. Each day they have grown stronger. By comparing this difference from day to day-r—"

WEIRD TALES

"I know how to calculate speed, Aaron. The point I still don't understand is this. That Mass out in space may be pointed at our earth right now. But our earth isn't stationary. We're revolving around the sun once every three-hundred and sixty-five days. Also, in the course of a year, our whole planetary system is moving at an incredible speed away from where it is now. In other words, our earth after each journey around the sun never returns to the identical spot from which it started. The Mass should miss us by a million miles."

"That's possible," admitted Carruthers. "And I'd like to believe you. Since, however, I've figured it out mathematically, I've come to the conclusion that your theory is not justified. The collision takes place ten years from this summer or fall. And that will be the end of the world, and of the Moon, too. A collision of such catastrophic proportions is bound to draw our Lunar neighbor into the earth's attraction so that the Mass, Moon and Earth will come together and merge into a sphere of flaming whiteness."

Vignot scoffed. "Phooey! Where is your copy of Einstein's calculator of variable factors of time and space?"

From his pocket Carmthers removed a leather-bound book and handed it to his colleague. Then he sat down.

"Very well," announced Vignot. "We'll see." He sprawled across the marble-topped table and began his tabulations which he fitted into complicated equations. From time to time his forehead wrinkled with thought. Then pure concentration erased everything from his face except a hard, purposeful glow in his eyes.

An hour passed with no interruption from either Carmthers or Danzig. They sat relaxed in their chairs, waiting. Vig-not's pencil covered scratch papers with numerals and symbols. Occasionally he blinked as the figures began to take on

meaning. Finally he pushed the papers aside and looked up.

"Your calculations agree with mine, Aaron. We'll have ten years of worry, floods, earthquakes, cyclones—then absolute chaos."

Carmthers said nothing for the moment. Instead he got to his feet, crossed the room to the quartz glass windows and stared uneasily across the roofs of the great city. After a time he turned from the window, walked to the table and examined Vignot's tabulations.

"You used a different arrangement of symbols and calculation devices than those I used," he acknowledged. "But you arrived at the same answer—the year of 2017. It looks," he added, "like absolute annihilation—which means the end of the world."

"I wish," sighed the bearded chemist, "you hadn't sent for me." He blinked owlishly. "Absolute annihilation beyond a doubt . . . unless . . . unless the earth's air barrier should prove heavy enough to turn it from its course. His eyes stopped blinking. Instead, they stared straight into those of the young scientist. "You propose to do something about this collision, Aaron. What?"

"I'm still mortal, Vignot, and human as the next man. What can I do?"

Vignot wagged his head impatiently. "That's not exactly what I meant. You've got something on your mind that you haven't yet explained to me. I want to hear it—now."

"Even if it means death before the Mass strikes the earth?"

"Even if it means death within the next twenty-four hours," snapped the bearded chemist.

THE voice of Aaron Carmthers became low and purposeful. "Ten years is a long time to wait for death especially when we know there is no way to avoid ■it. Yet,

CORE OF THE PURPLE FLAME

69

in those ten years, we will have ample time to erect our defenses and seek a way to destroy the Mass—if such a miracle is possible."

He paused as if searching for the right words. "Vignot," he continued. "Would you like to know today—now, just how fatal this coming catastrophe will be?"

"I don't quite understand."

"What I mean is this. Through the remarkable emanations of my Time Projector Machine, I can—"

"Don't do it." Karl Danzig was speaking for the first time. "You'd both be fools. There's nothing to be gained by submitting to such an experiment. You'd both be destroyed in the Thoridium Rays. I'm against the experiment utterly and completely."

"Quiet, Karl," advised Carruthers. "This is between Vignot and me."

"Ah!" sighed Vignot. "A difference of opinion. I never knew you two ever to disagree before. The prospect intrigues me. And since I don't expect, and don't want to live forever, I have little fear of death. Only I don't want to die by slow starvation. I want my meals regular. I want— Urnmm. Go ahead, Aaron. And please don't interrupt him, Karl. I'll weigh my chances of survival after hearing a few facts, then I'll make my decision."

"My plan," said Carruthers, "is to project our bodies into the year of 2017—"

"Impossible!" Vignot scoffed.

"Suicidal," added Danzig. "Let's abandon the whole business."

Carruthers eased his lanky body from the chair. He didn't smile, but there was a forceful, inner gleam in his eyes that lighted his whole face.

"There is no other way out for me," he told them, "but to go ahead with my plan. And once I have closed and locked the door to the Time Projector laboratory, I don't expect either of you men to violate my aloneness in that room. Should I come

out alive within the next twenty-four hours, I will have the answer to the earth's salvation in my head. Should I fail to return and unlock the door—the task of informing the world of its ultimate end lies with you both." He smiled then. "I guess that's all." With these words he left them and went swiftly down the corridor.

TJUT Aaron Carruthers was not alone -*-* when he reached the door to the Projector laboratory. Vignot and Danzig were close behind.

"So!" boomed Vignot. "You want to get rid of me now I'm here and have checked on your arithmetic. You want to make your experiment alone and leave me and Karl behind. Nonsense. We're in this crazy experiment as much as you are. Your dangers will be our dangers."

"Vignot's right," agreed Danzig. "I won't say another word, Aaron. Let's get started."

"I'm grateful to you both," sighed Carruthers, opening the door. "Come in, please. The room is more or less upset, but the apparatus is in perfect working order."

They entered.

"Hmmmm!" grunted the chemist. "What is this machine—an atom smasher?"

Carruthers nodded. "A variation of the main principle, but it goes much farther in its delving into the core of life. This ponderous machine, though much smaller than those giants in use at the government's research laboratories, has successfully bombarded that rare clement of Thoridium, atomic weight 319, "with heavy neutrons thereby stepping its weight up to 320. And since the even-numbered atoms are explosive, the Thoridium split into two parts creating the greatest energy ever produced by man."

He held up his hand as Vignot attempted to break in. "Wait a minute. Let me continue. This energy explosive and

WEIRD TALES

powerful though it is when harnessed to our new atomic motors, has produced a bi-product of weird potentialities. When I imprisoned this energy within a vacuum prism of Saigon's metallic glass, I became aware of a most singular phenomenon. This energy, when sealed in a vacuum, quickened the pulse of the universe, and shattered the world's yardstick of time. That is—the force of this newly-created energy is so potent, so far beyond anything man has yet dreamed of, that it moves faster than time itself. A paradox? Perhaps. But it is the sole actuating force of the Time Projector."

Vignot tugged at his beard. "These transparent walls around projector walls. What is their purpose?"

"Pure quartz. An outside as well as an inside wall with water between to keep the emanations from escaping. Karl, you'd better switch on our own power. I don't want to chance any fluctuation of the city current if I can help it. And phone the building engineer to start our basement dynamos."

A moment after Danzig had carried out these orders, the laboratory began to vibrate gently.

"There isn't much to be seen," explained Carruthers, "but the control board, the insulated chairs with their contact helmets, and the 21-inch circular prism of Saigon's metallic glass suspended between plastic posts which keeps the prism rigid."

He indicated the chairs. "Sit down, please, both of you. Karl, you take the chair near the power control station. Vignot, you sit in the center chair. And Til take the one on the right which enables me to control and regulate the forces sealed within the Thoridium power plant which actuates the Time Projector. Is it all clear?"

"Not quite," said Vignot. "This metal helmet . . ."

"Place it over your head the same as I'm

doing. And I'm warning you, Vignot, that you're goiog to be subject to some pain and bewildering sensations. Keep both palms on the metal handrests of the chair, and don't look at me, or at Danzig. Keep your eyes and mind focused on one point only —the Saigon prism."

He turned to the control panel beside him. "Now. I'll adjust the cycle of our explorations into the time period ten years in advance of this hour with an automatic shut-off just in case—"

"One more question," observed Vignot. "What part of us is it that goes forward in space?"

"All of us, and yet no part of us, for our bodies will actually remain here in these chairs. Always keep that in mind no matter what happens. We may be injured. We may be killed. But that will be in the future. And when the experiment has ended, we will find ourselves in these same chairs, neither injured or dead, but exactly as we are at this moment."

"Go ahead," snapped the chemist. "This waiting has become intolerable."

"Contact, Karl. The energy tube series first, using the odd numbers. Then switch to the even ones with a ten-second interval between. First contact. Good. Careful now—three, four, five—not yet—seven, eight, nine—contact points of the even-numbered series—Close your switch!"

FROM somewhere inside the laboratory came a sputtering crack. And across their field of vision shot a serpentine streamer of deep-red flame. It impinged against the prism and flowed over it like red dye.

Within the metal walls of the Thoridium power plant there was a sound like an imprisoned gale escaping. Carruthers listened for a disturbed moment, then he brought his mind back to the prism.

He saw it glowing redly then change slowly to orange and through the orderly

CORE OF THE PURPLE FLAME

71

prismatic scheme of yellow and blue to violet. He braced himself for whit lay beyond the violet. This was the breaking point between the present and the unknown future.

A gradual mistiness engulfed the laboratory, the prism and the Thoridium power plant.

The vibrations within the laboratory seemed to lessen in intensity. An eerie silence muffled all sounds. Almost imperceptibly the mist became denser. It enveloped the plastic posts like streamers of fog, then swirled around the glowing prism in a translucent, ghostly halo.

Its effect was hypnotic. He couldn't move his eyes. His mind lost its alertness and became sluggish. Slowly the violet glow faded into a color beyond the purple —a color he had never seen before.

This strange and unfamiliar hue distressed him, made him uneasy. He knew he was seeing something nature had never intended man to see, and in seeing it, he was being punished. Still, there was no way he could stop it. The experiment had passed beyond his control.

Restlessness crept over him in slimy coils of doubt. He felt light-headed and unstable as if his body was suspended over a deep abyss and would at any moment drop into black, terrifying silence that would last forever.

There were no thoughts in his mind of the other two men. The spell of the prism had erased them completely from his memory. He had even forgotten why he was sitting in the chair, staring at the scintillating, changing effulgence of the space-quickening prism.

It was then that lightness and darkness seemed to be struggling for supremacy. Dark would follow daylight. And daylight would follow dark. At first, these changes were slow and labored. Gradually, however, they quickened in tempo until the space between his eyes and the prism that

held them in thralldom flickered with lights and shadows.

He sensed, somehow, that these Bickerings were caused by the swift passage of days and nights. And he knew that he was moving forward into time.

How long he remained in this state of mind suspension he never knew. The end came following a torturous succession of sounds and sensations. He became aware of a monotonous ticking in his ears. Cold enveloped him that quickly changed to a devitalizing heat. Dimly, at first, he sensed a change in his surroundings. Things seemed to be the same, yet different. The prism suspended between the plastic posts was diminishing into space. To his ears, after the peculiar ticking had subsided, came strange sounds like the lament of thousands upon thousands of voices.

It was like a dirge of despair, of hope abandoned, of fear and anguish. It seemed purposeless and without meaning. Suddenly, and without warning, a ball of purple, eye-searing radiance exploded all around him.

The last link between the present and the future had snapped. In the vortex of the concussion some unseen force gripped him, and hurled his helpless body squarely into the core of this purple flame.

There was no pain, no sensation in this weird phenomenon. There was only for-getfumess and memory failure. He had successfully crossed the unknown abyss of ten years in less than seven earth minutes. And he never knew it.

Part II

STANDING before the quartz glass windows, Aaron Carruthers watched the exodus of human beings from the great city. Never had he seen the four-speed transportation bands so jammed with people.

The sight of the continuous stampede

WEIRD TALES

mads him sad. He knew why they were leaving the hot pavements of the city and fleeing to the seashore, lakes and rivers. He knew, also, that wherever they went, whatever they did, they could not escape. The world seemed doomed.

Each day the glowing Mass in the sky was drawing steadily nearer and increasing in size as it came closer. It was so bright that it could be seen by day. Its brilliance was like that of a small sun. And its heat more intense.

He turned from the window. As he reached his desk he noted the small calendar. The year of 2017 still had four months to go. Probably it would be the last year in the history of mankind. The door to the corridor was opening. Through it came Danzig and Vignot. Their faces were red and moist with sweat.

"It's what you might call warm outside, 1 ' complained the chemist. "And it isn't going to get any cooler either. Everybody is leaving the city. As a matter of fact all the cities are being abandoned. Wherever there is a lake, river or any body of water, the populace is flocking toward these blessed spots. Any news?" he finished.

"None," said Carruthers, grimly, "but what you already know."

"How is your Annihilator progressing?"

"Iu's about finished—or it should be. I'm making an inspection trip in a few minutes. Better come with me."

"You think it will work?"

Carruthers shrugged, and his jaw tightened. "How can I be absolutely certain. It should work by all the laws of science. At any rate, it's too late to worry as to whether it'll work or not. If it succeeds, we'll live to know. If it doesn't, I don't know as it will matter. We'll be nothing but powdered ashes. If you're ready now, we'll go to Thunder Mountain at once."

They left the laboratory, went to the roof and there boarded a rocket ship

which carried them north to the site of what might prove to be the world's last folly in scientific engineering.

From the air as the ship approached the landing field on top of Thunder Mountain towered a giant steei tube that at first glance seemed puny when viewed from the great heights of the air. But once the rocket ship had landed, and the men readied the workings, its monstrous size became apparent.

Through a new metallurgical process, the metal tube had been cast in a block without seams or rivets. It towered nearly three-hundred feet upwards from its base, and was roughly fifty feet in diameter. What the tube contained inside only a few men understood.

Irs purpose—to annihilate the approaching Mass of vegetation and earth by a continuous bombardment of its metal core with a concentrated beam of heavy neutrons. People, including many famous scientists, had scoffed at the sheer audacity of the idea. It was preposterous and doomed to failure.

Yet, in spite of opposition from all quarters, Aaron Carruthers had gone ahead perfecting the Annihilator. It had taken him years to figure out the construction and beam control. First there had been a small model which hadn't worked. That was the first setback. The metal of which he had constructed the first tube wouldn't stand up under the terrific onslaught of neutrons pouring from the electro-car-bonide rods. Even the best of the metallurgists had been unable to furnish him with the right kind of metal.

Quite by accident Carruthers discovered a formula he had once used to replace a Tungsten wire within a vacuum tube of an electronic oscillator resistor coil. Using this formula, he had constructed a second machine. The metal walls of the tube on this second machine not only took the beating from the neutrons, but also increased their

CORE OF THE PURPLE FLAME

73

power by keeping them into a solid beam that could be directed into space without endangering any metallic substance near at hand.

And this was the machine they had come to inspect. It had been erected on a high mountain away from any city. Its foundations were anchored deep in bedrock. Steel cables, their tension controlled by pneumatic shock absorbers, kept the metal tube from swaying in the high winds that constantly swept the mountain top.

Current for the dynamos beneath the structure came from a power-station at the base of the mountain. Yet no one knew, even Carruthers himself, whether this mammoth tube, pouring forth a controlled stream of annihilating neutrons, would be of sufficient power to break up the Mass hurtling toward the earth. But the young scientist had gone too far with his preparations to abandon them for something equally unpredictable. The Mass must be destroyed.

Even in the light of day men all over the world could see that it was coming steadily nearer and nearer. Occasionally it would flare into a white brilliance as it crashed into a meteor or wandering planetoid. But these collisions did not turn it aside. It came on and on, never swerving never slowing up.

Its heat spread out before it, increasing each day, Now the glowing Mass was in the east, now in the west as the earth circled lazily around the sun. The temperature continued to rise steadily night and day from seventy, to ninety, to a hundred and three. On this day it had readied a hundred and seven.

As Carruthers walked swiftly toward the metal structure that was destined to play so important a part in the world's salvation, the construction engineer came to meet him.

"It's no use, Carruthers," he said, grimly. "We're near the end of the job, but

not yet finished. All the men are quitting. It's too damned hot. They can't stand it."

"Hire more men," ordered Carruthers. "The work's got to go on. We can't stop now. Don't you understand the importance—?"

"I'm simply explaining' the facts."

"Hire more men as I said, and work them three hours a day at double pay for a full day's work."

"I'll do the best I can," nodded the engineer, "but I make no promises that the work will continue according to schedule. It isn't that the men don't want—" He stopped abruptly and stared stupidly at the young scientist.

The earth was trembling. A sudden flash of bluish light struck the top of the mountain, swirled like a miniature cyclone, then vanished in a thunderous, splitting crack. The shock knocked every man down.

Carruthers scrambled to his feet. He had known this was coming. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, enormous tides and floods all over the world would be the natural result of the approaching Mass. And his heart began to pound with unknown fears.

Yet there was no sign of fear on his face as he stood erect once more and then braced himself against the next ground upheaval. His eyes swerved upward. The steel tube was rocking perilously. One of the cables had come loose from its anchorage in the ground.

He raced toward its free end whipping crazily at the tube's base. But he never readied it. Something else claimed his attention. He kept on running to where the ground sloped away sharply, and checked suddenly on the raw edge of an earth crevasse six feet wide. He understood now why the cable had puiied ioose from its anchorage. The earth had split in a wide seam, and from it began to roll thick clouds of brownish smoke.

WEIRD TALES

Coughing, he stepped back and stumbled over a coil of rope. He gathered it up, fastened one end around the steel cable, and looped the free end around the base of a pine tree.

Hardly had he finished when the ground began to rock in a grinding movement from east to west. He dropped to his hands and knees. Smoke, pouring from the widening crevasse, enveloped him with noxious fumes.

His courage at that moment dropped to a low ebb. Was this to be the end of his years of patient and heart-breaking work? Was the world going to lose its one chance of survival because of an unpredictable eruption underground. He rubbed his eyes with the back of his hand. They were smarting from the fumes belching from the fissure.

Voices that were indistinct reached his ears. He closed his eyes against the smoke and staggered toward the sound. A hand closed around his arm and he heard Danzig speaking.

"We've got to get down from this mountain, Aaron. Some deep earthquake disturbance has almost split Thunder Mountain in two."

Carruthers continued to rub his eyes. "And leave the work of years unfinished, Karl?*' He shook his head. "You can go if you want to. You're under no obligation to remain. But I'm staving right here. I've work to do—work that can no longer be delayed. I wasn't prepared to start the bombardment. There's still a great deal of equipment lacking. However, I have no choice. Leave me alone now. Til carry on."

"But, Aaron. You can't. If these shocks continue, they'll cause the base of the Anni-hilator to disintegrate. It's almost ready to topple right now."

A gust of wind swirled across the mountain top driving the smoke away from the giant structure. "See?" pointed out the

young scientist. "The tube is still standing. And as long as it stands, I believe there is hope. I'm starting right now to unleash the heavy neutrons. There can be no more delay."

"And Tm going to remain with you," promised Danzig. Turning, he ran toward the steel hatchway leading inside the metal tube.

Carruthers started to follow. Then his eyes wandered toward the smoking crevasse some distance away. Even as he watched it. the distance across its top continued to widen. The wind slackened, and smoke billowed around him. Groping blindly, he crashed into George Vignot. Together both men stumbled toward the opening in the metal tube.

Danzig slammed the metal door shut. "I think we're all three of us fools, Aaron. We ought to have gone with the others. No telling how long this mountain will remain in existence."

Carruthers seemed not to have heard. He went at once to the glittering panel of his ether-vision machine. Seating himself before it he kicked a switch forward with his foot, clicked two more with his right hand, and slowly began to revolve a dial.

The silver surface of a magnetic vision screen became fogged and slightly agitated. This lasted but a few seconds until the space tubes warmed to their utmost efficiency. Then the silver of the magnetic screen faded slightly and turned to a greenish blue.

Noise flowed from the sound track, the crunch of running feet, of men gasping and panting. A second later the directional beam found them and reflected them on the screen. They were the workers, and they were fleeing down the mountain road to safety. Behind them crawled and billowed a dark, boiling liquid.

Carruthers reversed the scene until the directional beam slithered back up the mountain. He saw then the source of the

CORE OF THE PURPLE FLAME

75

dark liquid. It was flowing from the lower side of the crevasse halfway down the mountainside.

"Well," he sighed, "as long as nothing happens to the power lines, we'll be able to carry on. Check on all the mercury stabili2ers, Karl, so that the floor will be perfectly level. Force more of the mercury into the cylinders with the auxiliary pressure pump if you have to. Then, if the walls of our tube start rocking, the floor will remain on a level keel."

With eyes still on the magnetic screen he turned the directional beam on all points of the compass to determine the extent of the earth split. Both ends of the crevasse seemed to have curved away from the plateau on top of the mountain, so there seemed no immediate danger of the base of the Annihilator crumpling.

"I hope," sighed Vignot, tugging aimlessly at his beard, "that the commissary in connection with this venture is well stocked."

"So far as I'm aware," announced Car-ruthers, "there isn't a crumb of food on this mountain top." He placed a special filter over the magnetic screen and sat down. Turning the directional beam slowly, he focused it on the sky. Into the panel swam the menacing sky Mass.

He watched it for several minutes as if contemplating something evil. It looked larger than when he had first seen it that day in his own laboratory. He decided to bring it closer. Without taking his eyes from the magnetic screen he switched on the current generated by the Class Y motors. Beneath the screen a battery of infra-red tubes began to glow. The Mass in the sky began to quiver and expand.

The directional beam continued to bore outward under the increased power. The Mass came closer. Carruthers calculated swiftly. It would take five, no seven minutes before its glowing reflection entirely covered the magnetic screen.

He got up from before the ether-vision panel. "Open the hood at the top of the tube, KarL and set the angle of the annihilator beam at 29-97. That's where it should be at this hour and minute."'

Dials on the mercury cylinders register zero all around," announced Danzig. "The element of error appearing is minus two degrees from the west. That should change the angle of the annihilator beam to 29.95. Right?"

"Right," nodded Carruthers. "Set it at that angle. Everything ready to start now?"

"Everything's perfect."

"Good. Come over here and sit down. Keep an eye on the Class Y motors. I don't want anything to happen to them. Otherwise we wouldn't be able to look so far out into space." He examined the reflection of the Mass on the magnetic screen. It filled nearly two-thirds of it by now. He waited until the reflection of the Mass covered the entire screen, then set the dial and locked it against accidental turning.

Time for the fireworks, Karl." His voice was grim. "Afraid, either of you?"

"I'm merely hungry," Vignot grinned.

"And you, Karl?"

"No," said Danzig. "Give the Annihilator everything it's had built into it. If it's too much, we'll never know. If it's not enough, we'll have something to worry about."

CARRUTHERS smiled. "Here goes." He crossed the room, stared upward for a moment, then down at the insulating pad beneath his feet before the switchboard, took a deep breath and closed the circuit of the main switdi.

Blinding violet light curved down from a spot high in the tube. He staggered back from the switchboard, stunned but otherwise unhurt. Temporary blindness assailed him. He stood still for a moment waiting for his eyes to adjust themselves to the

WEIRD TALES

unearthly radiance bathing the inside of the metal walls.

A screeching howl filled the interior of the tube. It lasted for perhaps five seconds. Abruptly it changed to a high, thin hum. He groped his way back to the chair, his heart beating wildly. The die was cast. From now on there could be no turning back.

DANZIG thrust something in his hand. "Here. Put these on before you look up at the rods."

Carruthers adjusted the polaroid glasses to his eyes and looked upward into the flame-lashed vault of the tube. High above him glowed two electro-carbonide rods. They were tilted at an angle and their tips were ten inches apart. Across this gap poured streamers of violet fire. Where the flame points converged, there hung a ball nf white, pulsating fire. Unless there had been some error in calculations, billions upon billions of heavy neutrons were flowing in a concentrated beam into the sky straight upon the Mass that moved on the earth.

"How much power in reserve?" "Two million volts," said Danzig, "Step it up five-hundred thousand." Danzig bent forward. The whine of an unseen dynamo took on a swifter thrumming. "Five hundred thousand," he announced.

Carruthers watched the pulsing rays between the ends of the electro-carbonide rods, nodded approvingly, removed the polaroid glasses and walked to a small window set in what looked like a lead coffin. Inside this container was the heart of the Annihilator. Smoothly polished mirrors of the world's newest metal deflected the neutrons from their erratic courses and pointed them in a straight line toward the target they were supposed to hit and destroy.

There was no immediate way of knowing whether the neutrons were impinging

against the metal core of the Mass, or whether they were wasting themselves in sky space millions of miles from the target. Astronomical observers had given Carruthers the exact angle in relation to the mountain top where the machine had been erected. Now there was nothing more to do but to keep blasting away at the target.

Minutes passed into hours. No one spoke. There seemed nothing anyone could do or say. As the earth turned on its axis, the stream of neutrons from the Annihilator was kept on the target by the automatic adjuster.

When the Mass reached the far western horizon and was no longer visible, Carruthers shut off the power. There was nothing more to be done until the Mass appeared in the eastern sky at dawn.

He turned to Danzig. "Karl, we have no electronic phones, nor have we any means of keeping in touch with the outer world save with our ether-vision machine. While we can see with this, we can't talk or act. Our success in carrying out this experiment depends solely on the current we are receiving from the power-station at the big dam near the base of the mountain. Go there at once. And don't let anyone shut off that power."

"That's all very well," boomed Vignot. "But you can't expect me to stay cooped up here. Surely tfaere must be something I can do . . ."

"There is," said Carruthers, "much as I hate to have you leave. I would like to know the full extent of the disturbance that rocked this mountain and nearly split it in two. If there has been a ground shift of even a few degrees, it might well throw off all our calculations. I don't believe, however, that the slippage of earth has been upward. More than likely it has been downward so that its movement disturbed only surface soil and not the basic rock."

"It'll take time, Aaron. Ml have to

CORE OF THE PURPLE FLAME

77

walk until I can find some faster mode of travel. But I'll return as soon as I can." The three men shook hands. Their eyes met. If they wondered whether they'd ever see each other alive again, they showed no signs of it. A moment later, Aaron Car-ruthers was alone in the giant metal tube on Thunder Mountain.

MORNING found him at the controls again, a little haggard and more than a little worried. No one had come up the mountain with food. Meanwhile the temperature had risen to 115 degrees.