Figure 1. Adapted from Darwin.

The lamentation in Psalm 13 is expressed thus: ‘How long wilt thou forget me, O Lord? For ever? How long wilt thou hide thy face from me?’ In Psalm 17 we read ‘As for me I will behold thy face in righteousness; I shall be satisfied, when I awake, with thy likeness’. The fourth psalm implores God to lift up ‘the light of your countenance upon us’. Clearly we have moved a long way from the Torah. The hope of a face-to-face encounter fills the Psalms from beginning to end, and the hope is turned to a promise by the Apostle Paul, who tells us that now we see through a glass darkly, ‘but then face to face’. God’s face, which Moses was forbidden to see, is now at the centre of faith and hope, and the way to it, Paul says, is agape, the New Testament word for neighbour love, translated as caritas in the Vulgate and described by Kant as the ‘love to which we are commanded’.

What is meant by the ‘face of God’? This will be the theme of my remaining chapters. And the obvious starting point, given the argument of the last chapter, is the human face: what is it, exactly, what role does it play in inter-personal relations, and what is its fate in the age in which we live? The theme of the face is familiar from a certain kind of continental philosophy, and Emmanuel Levinas has devoted pages of tantalizing obscurity to expounding it. The face, writes Levinas, is ‘in and of itself visitation and transcendence’:1 and by this he seems to mean that the face comes into our shared world from a place beyond it, while in some way remaining beyond it, always just out of reach. This is the thought that I wish to explore. And I want to bring this all-important topic within the purview of philosophy as we know it in the English-speaking world – philosophy as argument, whose goal is truth. Levinas belongs to another tradition – the tradition of the prophets and mystics, who pursue dark thoughts at the edge of language, and who cast shadows over all that they approach.

Many animals have eyes, nostrils, lips and ears disposed in ways that resemble the disposition of the human face. And many animals recognize each other by their features. But would it be right to say that they have faces, and direct their attention to the face when relating to their companions? And what kind of questions are those? Can they be answered by empirical investigation, or are they bound up with ontological distinctions that lie deeper than the study of behaviour? In a famous book, Darwin set out to show that the expression of emotion in humans resembles its expression in other animals, and he gave examples that were supposed to show this.2 The human face, he thought, is distinguished by its mobility, but not by its role in social communication. Emotions and motives are expressed in the face, so enabling other members of the species to anticipate behaviour, whether aggressive, appeasing, amorous, retreating or alarmed.

The dog, the swan and the person illustrated in Figure 1 display what Darwin took to be variations on a single pattern, in which teeth are bared or bill primed for attack, defences raised, and vulnerable features withdrawn for protection. Part of Darwin’s purpose in showing such images was to indicate that our emotions are evolved responses, many of which we share with other species, and which reflect the background circumstances of our life as vulnerable organisms.

It is certainly true that faces, like any other part of the body, can display the forces that act on them – in that sense they can function as what the philosopher Paul Grice called ‘natural signs’.3 Grice expressly distinguished such natural signs from the human act of meaning something. Animals can read natural signs: a horse notices the laid back ears of its neighbour and gets out of the way; a dog recognizes the submissive gestures of its antagonist and ceases to fight. But this does not mean either that animals can mean things as we mean them, or that they see what we see, when we see the expression in a face. We have to ask ourselves what advantage it would be to an animal, that it could see faces, as well as the clues to future behaviour that they contain? Surely, none that we could fathom. The face, for us, is an instrument of meaning, and mediates between self and other in ways that are special to itself.

Figure 1. Adapted from Darwin.

Grice’s theory of meaning has spawned a vast literature that I must pass over here. But one central strand in his argument deserves mention. Grice was concerned to analyse the act of meaning something – ‘speaker’s meaning’. Meaning something involves an intentional action, but not all intentional actions are ways of meaning something. According to Grice, meaning involves an additional, ‘second order’, intention namely, the intention that the other should grasp the content of my action by recognizing that that is my intention. Leaving aside all subsequent refinements and qualifications, Grice’s insight can be understood as capturing the I–You nature of meaning. In meaning something I am addressing you as another subject, with the intention that you recognize the subject in me. This immediately lifts what Grice called ‘non-natural’ meaning out of the repertoire of animal behaviour, and confers upon it a distinctively inter-subjective character.

The expression on a face is not normally intentional. An actor may intend his face to wear an expression of fear or anger: but the intention is to replicate what is unintentional. Nevertheless it is important that the face is the part of the body on which intention is inscribed, in the form of words, glances, nods and shakes. When we read the face we are aware of this. Facial expressions are where meaning lies; hence they serve as the natural sign of self-conscious and inter-personal states of mind.

Animals don’t have the concept of the face – for this is a concept bound up with distinctions that only language users can make. But it does not follow that they don’t recognize faces. After all no horse has the concept of a horse; but every horse recognizes horses, and is able to distinguish horse from non-horse in its environment. Animals are also able to discriminate objects on the basis of Gestalten – overall outline and similarity of form – even when this is not the result of a piecemeal similarity of parts. Birds are especially gifted in this respect and can recognize individual people on the basis of outline or facial features.4 Nevertheless it seems redundant to describe an animal as recognizing something or someone by the face, rather than by the component features such as nose, brow, eyes and colouring. Maybe there are people who are like animals in this respect: who are unable to understand faces as faces but who yet recognize people by their features. Maybe such a person reasons (sub-consciously) as follows: long ears, wide-set eyes, large lips, high cheek-bones – yes, that’s Bill. But such reasoning falls short of the capacity that we have, which is to see Bill in his face, and to see that face as a you and therefore an I. This capacity lies beyond the repertoire of birds and other animals. Nor, I would suggest, do the non-human apes possess it, even though they can ‘recognize’ themselves in mirrors – that is to say, understand from a mirror image that what they see there is some part of their own body.5

Hence you could imagine a person being face-blind as animals are face-blind, even if he is not blind to all the components that make up faces – perhaps some cases of prosopagnosia are like this. The case would resemble what Wittgenstein calls ‘aspect blindness’ – as when someone can see everything that composes the image in a picture but cannot see the image. (I suspect that ‘tone deaf’ people are like this: they hear all the sounds that compose the musical argument, but cannot hear the music that others hear in the sounds.) Seeing a face as a face means going beyond the physical features in some way, to a whole that emerges from them as a melody emerges from a sequence of pitched sounds, and which is, as Levinas aptly says, both a visitation and a transcendence.

I have an idea of transcendence from my own case. My face is one part of me that I do not see – unless, that is, I set out to see it, by using a mirror. People are surprised by their own face, in the way that they are not surprised by any other part of their body or by the face of another person. It is through the sight of their own face that they have the sense of what they are for others, and what they are as others. (They have this sense from hearing their own voice in a recording, and this too is the occasion of surprise and often discomfiture.) In the story of Narcissus the protagonist responds to himself as another, through confronting his own face. Until that moment he had been locked in himself – unable to acknowledge others and fleeing from their love. Tiresias had prophesied that Narcissus would live to a ripe old age if only ‘he will not know himself’.6 Catching sight of his own face in the pool Narcissus finds himself ‘looked into’ for the first time: he knows himself, but not as himself. He encounters a subject who flees from him as he had fled from others. And because he does not turn away, Narcissus is destroyed by what he sees.

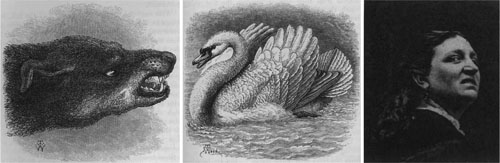

My face is also the part of me to which others direct their attention, whenever they address me as ‘you’. I lie behind my face, and yet I am present in it, speaking and looking through it at a world of others who are in turn both revealed and concealed like me. My face is a boundary, a threshold, the place where I appear as the monarch appears on the balcony of the palace. (Hence Dante’s apt description, in the Convivio, of the eyes and the mouth as ‘balconies of the soul’.) My face is therefore bound up with the pathos of my condition. In a sense you are always more clearly aware than I can be of what I am in the world; and when I confront my own face there may be a moment of fear, as I try to fit the person whom I know so well to this thing that others know better. How can the person, whom I know as a continuous unity from my earliest days until now, be identical with this decaying flesh that others have addressed through all its changes? This is the question that Rembrandt explored in his lifelong series of self-portraits. For Rembrandt the face is the place where the self and the flesh melt together, and where the individual is revealed not only in the life that shines on the surface but also in the death that is growing in the folds (Figure 2). The Rembrandt self-portrait is that rare thing – a portrait of the self. It shows the subject incarnate in the object, embraced by its own mortality, and present like death on the unknowable edge of things.

Figure 2. Rembrandt: Self Portrait.

When we speak of the person as lying behind his face we are speaking figuratively. Obviously he is not identical with his face; but that does not imply that he is wholly other than his face, still less that he is a clandestine soul, hidden behind the flesh like a clown behind his grease-paint. The natural signs that dogs read in the features of their fellow dogs are transparent effects of the passions that compel them. But the face of the human being is not in the same way transparent. People can deceive through their faces, and can use their faces to shape the world in their own favour. In Macbeth Duncan regrets having been taken in by the treacherous Thane of Cawdor, Macbeth’s predecessor in that title, saying ‘There is no art/ To find the mind’s construction in the face’: meaning that there is no way you can be instructed to discover what lurks behind a deceiving smile. The play proves Duncan right, since he is at once taken in by Macbeth, who murders him.

This possibility of deception arises precisely because we do not make a distinction, in our ordinary encounters, between a person and his face. When I confront another person face to face I am not confronting a physical part of him, as I am when, for example, I look at his shoulder or his knee. I am confronting him, the individual centre of consciousness, the free being who reveals himself in the face as another like me. There are deceiving faces, but not deceiving elbows or knees. When I read a face I am in some way acquainting myself with the way things seem to another person. And the expression on a face is already an offering in the world of mutual responsibilities: it is a projection in the space of inter-personal relations of a particular person’s ‘being there’. To put it in another way: the face is the subject, revealing itself in the world of objects.

That the face has this character is in part due to the larger significance of the human body. Thanks to our upright posture, our liberated forearms, and our all-seizing hands we are able to face things not merely with our eyes but with our whole being. This posture penetrates our intentional understanding in subtle ways that have been in part clarified by Merleau-Ponty.7 The human face announces the human body and precedes it like an ensign. And our reading of the face reflects this. The face occurs in the world of objects as though lit from behind. Hence it becomes the target and expression of our inter-personal attitudes, and looks, glances, smiles become the currency of our affections.

This means that the human face has a kind of inherent ambiguity. It can be seen in two ways – as the vehicle for the subjectivity that shines in it, and as a part of the human anatomy. The tension here comes to the fore in eating, as has been argued by Leon Kass and Raymond Tallis.8 We do not, as animals do, thrust our mouths into our food in order to ingest it. We lift the food to our mouths, while retaining the upright posture that enables us to converse with our neighbours. In all societies (prior to the present) eating is a social occasion, with a pronounced ritual character, often preceded by a prayer of thanks. It occurs in a space that has been sanctified and ritualized, and into which the gods have been invited. All rituals impose discipline on the face, and this is part of what we experience when eating. However, the ordered nature of the food-to-face encounter goes beyond ritual discipline. Table manners have the function of maintaining the face and the mouth in their personal and conversational aspect. The well-mannered mouth is not just a mouth, and certainly not an aperture through which food is ingested. It is the place of the voice, the outlet of thought and feeling, a ‘balcony of the soul’. And when people scoff greedily – especially when they do so in the solitary and needy manner that is becoming common – the mouth and the face change aspect, to become merely anatomical, their personal significance wiped out.

Of course, there is a balancing act here, and most people fall a little bit short, and indeed must fall short if they are not to appear prissy and precious at the dinner table. The crucial point is that even when serving a biological purpose, my face remains under my jurisdiction. It is the place where I am in the world of objects, and the place from which I address you. And the face has an interesting repertoire of adjustments, which cannot be understood merely as physical changes of the kind that we observe in the features of other species. For example there is smiling. Animals do not smile: at best they grimace, in the manner of chimpanzees and bonobos. In Paradise Lost, Milton writes (describing the love between Adam and Eve) that ‘smiles from reason flow,/ To brute denied, and are of love the food’. The smile that reveals is the involuntary smile, the blessing that one soul confers upon another, when shining with the whole self in a moment of self-giving. Hence the voluntary and deliberately amplified smile is not a smile at all but a mask. One of the greatest smiles in all painting is that bestowed on Rembrandt by his aged mother, and by Rembrandt on her (see Figure 3). Here the mouth is barely inflected, and the eyes, dull with age, are nevertheless bright with maternal affection. Very few paintings present so vivid an instance, of the subject revealed in the face. We, the viewers, know what it is like for this woman, to look in this way on her son.

Smiling is one way of being present in the face; another way is kissing. Whereas a sincere smile is involuntary, a sincere kiss is willed. That is true, at least, of the kiss of affection. In the kiss of erotic passion, however, the will is also in part overcome and in this context the purely willed kiss has an air of insincerity. The sincere erotic kiss is both an expression of will and a mutual surrender. Hence it requires a kind of government of the mouth, so that the soul can breathe out from it, and also surrender there, on the perimeter of one’s being. Describing the temptation and fall of Francesca da Rimini, Dante writes of Francesca recalling the moment when she and Paolo read together the story of Lancelot and Guinevere, and reached the passage where Lancelot falls victim to Guinevere’s smile. She remembers reading how the fond smile was ‘kissed by such a lover’. She then recalls Paolo kissing, not her smile, for she was no longer smiling, but her mouth. And through her mouth she participates in Paolo’s trembling: la bocca mi baciò tutto tremante (Inferno, V, 136). The mouth, like the eye, is a point of intersection of soul and body, person and animal. Francesca has been aware, through Guinevere, of her own smile, since she has been aware of the freedom of choice that is prompting her love. Then Paolo kisses her, and her smile becomes a mouth, full of trembling. She attributes this trembling to Paolo: and we sense how Francesca’s self-image has been vanquished. She experiences her desire as a force from outside, an overcoming, which she is powerless to resist, since it has been transferred to the I.

Figure 3. Rembrandt: The Artist’s Mother.

The erotic kiss is not a matter of lips only: still more are the eyes and the hands involved. And surely Sartre is right to think that, in the caress of desire I am, as he puts it, seeking to ‘incarnate the other’ – in other words, I am seeking to bring into the flesh that I touch with my hands or lips, the thing that Sartre calls freedom, and which I am calling the first person perspective.9 Sartre goes on to argue that sexual desire is inherently paradoxical, since it can succeed in its aim only by ‘possessing another in his freedom’ – in other words possessing another’s freedom while also removing it. I don’t agree with that. But I do think that the kiss of desire brings into prominence the very same ambiguity in the face that is present in eating. The lips offered by one lover to another are replete with subjectivity: they are the avatars of I, summoning the consciousness of another in a mutual gift. This is how the erotic kiss is portrayed by Canova, for example, in his sculpture of Eros and Psyche, Figure 4, and also by Rodin in ‘The Kiss’, a work that was originally called ‘Paolo and Francesca’.

The lips are offered as spirit, but they respond as flesh. Pressed by the lips of the other they become sensory organs, bringing with them all the fatal entrapment of sexual pleasure, and ready to surrender to a force that breaks into the I from outside. Hence the kiss is the most important moment of desire – the moment in which soul and body are united, and in which lovers are fully face to face and also totally exposed to one another, in the manner that Francesca describes. The pleasure of the kiss is not a sensory pleasure: it is not a matter of sensations, but of the I–You intentionality and what it means. Hence there can be mistaken kisses, and mistaken pleasure in kissing, as was experienced by Lucretia, in Benjamin Britten and Ronald Duncan’s version of the story, kissing the man she thought to be her husband, and whom she discovered to be the rapist Tarquin, though too late to defend herself.

Figure 4. Canova: Eros and Psyche.

The presence of the subject in the face is yet more evident in the eyes, and eyes play their part in both smiles and looks. Animals can look at things: they also look at each other. But they do not look into things. Perhaps the most concentrated of all acts of non-verbal communication between people is that of lovers, when they look into each other’s eyes. They are not looking at the retina, or exploring the eye for its anatomical peculiarities, as an optician might. So what are they looking at or looking for? The answer is surely obvious: each is looking for, and hoping also to be looking at, the other, as a free subjectivity who is striving to meet him I to I.

To turn my eyes to you is a voluntary act. But what I then receive from you is not of my doing. As the symbol of all perception the eyes come to stand for that ‘epistemic transparency’ which enables the person to be revealed to another in his embodiment – as we are revealed in our looks, smiles, and blushes. The joining of perspective that is begun when a glance is answered with a blush or a smile finds final realization in wholly reciprocated glances: the ‘me seeing you seeing me’ of rapt attention, where neither of us can be said to be either doing or suffering what is done. Here is Donne’s description:

Our eye-beams twisted, and did thred

Our eyes, upon one double string:

So to’entergraft our hands, as yet

Was all the meanes to make us one,

And pictures in our eyes to get

Was all our propagation.

Looks are voluntary. But the full revelation of the subject in the face is not, as a rule, voluntary. Milton’s observation, that ‘smiles from reason flow’, is fully compatible with the fact that smiles are usually involuntary, and ‘gift smiles’, as one might call them, always so. Likewise laughter, to be genuine, must be involuntary – even though laughter is something of which only creatures with intentions, reason, and self-consciousness are capable. Laughter is a topic in itself, and I must pass over it here.10 The important point is that, while smiling and laughing are movements of the mouth, the whole face is infused by them, so that the subject is revealed in them as ‘overcome’. The light grey eye of Isabel Archer, as Henry James describes her, ‘had an enchanting softness when she smiled’ – a softness that could be noticed only by the person who also saw the smile on her lips, and felt the change in her features as an involuntary outflow of pleasure.

Tears of merriment flow from the eyes, so too do tears of grief and pain. Hence tears are symbols of the spirit: it is as though something of me is lost with them. For this reason people have since ancient times felt the impulse to collect their tears in lachrymatories. Psalm 56, v. 8, laments to God ‘Thou tellest my wanderings, put Thou my tears in Thy bottle; are they not in Thy Book?’ Tears are like pains: they cannot be voluntary, even if you can do something else in order to produce them. Although there are actors and hypocrites who can produce tears at will, that does not make tears into intentional actions; it just means that there are ways of making the eyes water without producing ‘real tears’. But laughing and smiling can be willed, and when they are willed they have a ghoulish, threatening quality, as when someone laughs cynically, or hides behind a knowing smile. Voluntary laughter may also be a kind of spiritual armour, with which a person defends himself against a treacherous world.

Similar observations apply to blushes, which are more like tears than laughter in that they cannot be intended. What Milton says about smiles could equally be said of blushes. Blushes from reason flow, to brute denied, and are of love the food. Only a rational being can blush, even though nobody can blush voluntarily. Even if, by some trick, you are able to make the blood flow into the surface of your cheeks, this would not be blushing but a kind of deception. And it is the involuntary character of the blush that conveys its meaning. Mary’s blush upon meeting John, being involuntary, impresses him with the sense that he has summoned it – that it is in some sense his doing, just as her smile is his doing. Her blush is a fragment of her first person perspective, called up onto the surface of her being and made visible in her face. In our experience of such things our sense of the animal unity of the other combines with our sense of his unity as a person, and we perceive those two unities as an indissoluble whole. The subject becomes, then, a real presence in the world of objects.

It is, I hope, not too fanciful to extend this phenomenology of the face a little further, and to see the face as a symbol of the individual and a display of his individuality. People are individual animals; but they are also individual persons, and as I argued in the last chapter, there is a puzzle as to how they can be both. On one tradition – that associated with Locke – the identity of the person through time is established by the continuity of the ‘I’, and not by reference to the constancy of the body. Although I don’t accept this, I do accept that being a person has something to do with the ability to remember the past and intend the future, while holding oneself accountable for both. And this connection between personality and the first person case has in turn something to do with our sense that human beings are individuals of a special kind and in a special sense that distinguishes them from other spatio-temporal particulars. The knowledge that I have of my own individuality, which derives from my direct and criterionless awareness of the unity that binds my mental states, gives substance to the view that I am maintained in being as an individual, through all conceivable change. The Istigkeit or haecceitas is exemplified in me, as something that I cannot lose. It is prior to all my states and properties and reducible to none of them. In this I am god-like too. And it is this inner awareness of absolute individuality that is translated into the face and there made flesh. The eyes that look at me are your eyes, and also you: the mouth that speaks and cheeks that blush are you.

The sense of the face as irradiated by the other and infused with his self-identity underlies the power of masks in the theatre. In the classical theatre of Greece, as in that of Japan, the mask was regarded not only as essential to the heightened tension of the drama, but also as the best way to guarantee that the emotions expressed by the words are reflected in the face. It is the spectator, gripped by the words, who sees their meaning shining in the mask. The impediment of human flesh and its imperfections has been removed, and the mask appears to change with every fluctuation of the character’s emotions, to become the outward sign of inner feeling, precisely because the expression on the mask originates not so much in the one who wears it as in the one who beholds it. To make a mask that can be seen in this way requires skills acquired over a lifetime – perhaps more than a lifetime, the mask-makers of the Noh theatre of Japan handing on their art over many generations, and the best of the masks being retained in the private collections of patrons and performers, to be brought out only on occasions of the greatest solemnity.

The mask was a symbol of Dionysus, the god at whose festival the tragedies were performed. It did not signify the god’s remoteness from the spectators – Dionysus was no deus absconditus. It signified his real presence among them. Dionysus was the god of tragedy and also the god of rebirth, conveyed by the wine into the soul of his worshippers, so as to include them in the dance of his own resurrection. The mask was the face of the god, sounding on the stage with the voice of human suffering, and sounding in the mystery cult with a divine and dithyrambic joy.

It is significant that the word ‘person’, which we borrow to express all those aspects of the human being associated with first-person awareness, came originally from the Roman theatre, where persona denoted the mask worn by the actor, and hence, by extension, the character portrayed.11 By borrowing the term the Roman law signified that, in a certain sense, we come always masked before judgement. As Sir Ernest Barker once put it: ‘it is not the natural Ego which enters a court of law. It is a right-and-duty bearing person, created by the law, which appears before the law.’12 The face, like the person, is both product and producer of judgement.

We should recognize too that it is not only in the theatre that masks are used. There are societies – that of Venice being the most singular – in which masks and masquerades have acquired complex functions that bring them into the very centre of communal life, to become indispensable items of clothing, without which people feel naked, indecent or out of place. In the Venetian Carnival the mask traditionally served two purposes: to cancel the everyday identity of the person, and also to create a new identity in its place – an identity bestowed by the other. Just as in the theatre the mask wears the expression projected onto it by the audience, so in the Carnival does the mask acquire its personality from the people all around. Hence, far from cutting people off from each other, the collective act of masking makes each person the product of others’ interest: the moment of Carnival becomes the highest form of ‘social effervescence’, to use Durkheim’s pregnant phrase.

In his remarkable study of the Venetian mask the historian James Johnson has explored the way in which, over many centuries, the role of the mask evolved, as one might put it, from hiding to framing. The Venetian mask became a way not of concealing the wearer but of endowing him with an ‘incognito’ presence; the mask was both transparent to his real identity and yet a barrier, a threshold, behind which he stood in a space of his own. At the height of its use, in the eighteenth-century Venice of Goldoni and Gozzi, the mask ceased to be a retreat from the world, and became instead a way of entering it, an instrument of freedom and a ceremonial acknowledgement of the public world. As Johnson puts it, the mask ‘was a token of privacy instead of the real thing, a manufactured buffer that licensed genuine aloofness and unaccustomed closeness. Its ritualized “anonymity” could be acted on or ignored at will. The mask honoured liberty in the Venetian sense, which meant a measure of autonomy within jealously guarded limits’.13

The mask shows that the individualized face of the other is, in a certain measure, our own creation: remove the mask and beneath it you find a mask (Figure 5). This observation leads to a certain anxiety, since it suggests that the other’s presence in his face may be no more real than his presence in the mask. Perhaps we are even mistaken in attributing to persons the kind of absolute individuality that we unavoidably see in their features. Maybe our everyday interactions are more ‘carnivalesque’ than we care to believe, the result of a constant and creative imagining that behind each face lies something like this – namely, the inner unity with which we are acquainted and for which none of us has words.14 Maybe the individuality of the other resides merely in our way of seeing him, and has little or nothing to do with his way of being.

I am inclined to the view that there is no answer to the question what makes me the individual that I am that is not a trivial assertion of identity. But I am also inclined to the view that the notion of an absolute individuality arises spontaneously from the most fundamental inter-personal relations. It is implied in all our attempts at integrity and responsible living. And it is built into our way of perceiving as well as our way of describing the human world. Rather than dismiss it as an illusion, I would prefer to say that it is a ‘well-founded phenomenon’, in Leibniz’s sense, a way of seeing the world that is indispensable to us, and which we could never have conclusive reason to reject.

Figure 5. Lorenzo Lippi: Woman with Mask and Pomegranate.

Moreover, the face has this meaning for us because it is the threshold at which the other appears, offering ‘this thing that I am’ as a partner in dialogue. This feature goes to the heart of what it is to be human. Our inter-personal relations would be inconceivable without the assumption that we can commit ourselves through promises, take responsibility now for some event in the future or the past, make vows that bind us forever to the one who receives them, and undertake obligations that we regard as untransferable to anyone else. And all this we read in the face.

Especially do we read those things in the face of the beloved in the look of love. Our sexual emotions are founded on individualizing thoughts: it is you whom I want and not the type or pattern. This individualizing intentionality does not merely stem from the fact that it is persons (in other words, individuals) whom we desire. It stems from the fact that the other is desired as an embodied subject, and not as a body.15 And the embodied subject is what we see in the face.

You can see the point by drawing a contrast between desire and hunger. Suppose that people were the only edible things; and suppose that they felt no pain on being eaten and were reconstituted at once. How many formalities and apologies would now be required in the satisfaction of hunger! People would try to conceal their appetite, and learn not to presume upon the consent of those whom they surveyed with famished glances. It would become a crime to partake of a meal without the meal’s consent. Maybe marriage would be the best solution. Still, this predicament is nothing like the predicament in which we are placed by desire. It arises from the lack of anything impersonal to eat, but not from the nature of hunger. Hunger is directed towards the other only as object, and any similar object will serve just as well. It does not individualize the object, or propose any other union than that required by need. Still less does it require of the object those intellectual, moral and spiritual virtues that the lover might reasonably demand – and, according to the literature of courtly love, must demand – in the object of his desire.

When sexual attentions take the form of hunger they become deeply insulting. And in every form they compromise not only the person who addresses them, but also the person addressed. Precisely because desire proposes a relation between subjects, it forces both parties to account for themselves: it is an expression of my freedom, which seeks out the freedom in you. Hence modesty and shame are part of the phenomenon – a recognition that the ‘I’ is on display in the body, and its freedom in jeopardy. This we see clearly in Rembrandt’s painting of Susanna and the Elders, Figure 6, in which Susanna’s body is made to shrink into itself by the prurient eyes that observe her, like the flesh of a mollusc from which the shell has been prised.

Unwanted advances are therefore also forbidden by the one to whom they might be addressed, and any transgression is felt as a contamination. That is why rape is so serious a crime: it is an invasion of the victim’s freedom, and a dragging of the subject into the world of things. I don’t need to emphasize the extent to which our understanding of desire has been influenced and indeed subverted by the literature, from Havelock Ellis through Freud to the Kinsey reports, which has purported to lift the veil from our collective secrets. But it is worth pointing out that if you describe desire in the terms that have become fashionable – as the pursuit of pleasurable sensations in the private parts – then the outrage and pollution of rape become impossible to explain. Rape, on this view, is every bit as bad as being spat upon: but no worse. In fact, just about everything in human sexual behaviour becomes impossible to explain – and it is only what I have called the ‘charm of disenchantment’ that leads people to receive the now fashionable descriptions as the truth.

Figure 6. Rembrandt: Susanna and the Elders.

Rape is not just a matter of unwanted contact. It is an existential assault and an annihilation of the subject. This fact has seldom been more poignantly captured than by Goya, in one of his paintings devoted to scenes of brigandage. The girl in this painting (Figure 7) is being relieved of her clothes by her captors, who handle the precious stuff with a concupiscent delicacy that is all the more excruciating in that we know how they are about to handle her. She hides from them, not her body but her face, the place where her shame is revealed, and by hiding which she does all that she can to withdraw herself from what is about to happen.

Sexual desire is inherently compromising, and the choice to express it or to yield to it is an existential choice, in which the self is at risk. Not surprisingly, therefore, the sexual act is surrounded by prohibitions; it brings with it a weight of shame, guilt and jealousy, as well as joy and happiness. Sex is therefore deeply implicated in the sense of original sin, as I described it earlier: the sense of being sundered from what we truly are, by our fall into the world of objects.

There is an important insight contained in the book of Genesis, concerning the loss of eros when the body takes over. Adam and Eve have partaken of the forbidden fruit, and obtained the ‘knowledge of good and evil’ – in other words the ability to invent for themselves the code that governs their behaviour. God walks in the garden and they hide, conscious for the first time of their bodies as objects of shame. This ‘shame of the body’ is an extraordinary feeling, and one that no animal could conceivably have. It is a recognition of the body as in some way alien – the thing that has wandered into the world of objects as though of its own accord, to become the victim of uninvited glances. Adam and Eve have become conscious that they are not only face to face, but joined in another way, as bodies, and the objectifying gaze of lust now poisons their once innocent desire. Milton’s description of this transition, from the pure eros that preceded the fall, to the polluted lust that followed it, is one of the great psychological triumphs in English literature. But how brilliantly and succinctly does the author of Genesis cover the same transition! By means of the fig leaf Adam and Eve are able to rescue each other from the worst: to ensure, however tentatively, that they can still be face to face, even if the erotic has now been privatized and attached to the private parts.

Figure 7. Goya: Scene of Brigandage.

In his well-known fresco of the expulsion from Paradise, Masaccio shows the distinction between the two shames – that of the body, which causes Eve to hide her sexual parts, and that of the soul, which causes Adam to hide his face (Figure 8). Like the girl in Goya’s picture, Adam hides the self; Eve shows the self in all its confused grief, but still protects the body – for that, she now knows, can be tainted by others’ eyes.

I have dwelt on the phenomenon of the erotic because it illustrates the importance of the face, and what is conveyed by the face, in our personal encounters, even in those encounters motivated by what many think to be a desire that we share with other animals, and which arises directly from the reproductive strategies of our genes. In my view sexual desire, as we humans experience it, is an inter-personal response – one that presupposes self-consciousness in both subject and object, and which singles out its target as a free and responsible individual, able to give and withhold at will. It has its perverted forms, but it is precisely the inter-personal norm that enables us to describe them as perverted. Sexual relations between members of other species have, materially speaking, much in common with those between people. But from the intentional point of view they are entirely different. Even those creatures who mate for life, like wolves and geese, are not animated by promises, by devotion that shines in the face, or by the desire to unite with the other, who is another like me. Human sexual endeavour is morally weighted, as no animal endeavour can be. And its focus on the individual is mediated by the thought of that individual as a subject, who freely chooses, and in whose first person pespective I appear as he or she appears in mine. To put it simply, and in the language of the Torah, human sexuality belongs in the realm of the covenant.

Figure 8. Masaccio: Expulsion from Paradise.

Someone might respond by saying that I have described what is at best an ideal, and that the reality may be very different. Our world abounds in sexual practices that ignore or by-pass the subjectivity of the other – sexual encounters in dark rooms where the face cannot be seen, encounters with ‘real dolls’ that respond with a caricature of human excitement, encounters imagined through the screen or vicariously enjoyed through pornography, voyeurism and video sex-games. But I would reply that, in almost all cases where we do not refer directly to perversion (as in bestiality and necrophilia) the object of sexual interest is being treated as a substitute: the object is the imaginary other, the fantasy subject, and serves a sexual purpose precisely by being tied in my imagination to the real desiring me. Objects can be substitutes for subjects as the target of sexual excitement, but they cannot replace them. It is not the shoe that the fetishist desires, but the imaginary woman with whose aura it is filled.

Hence there is an important sense in which human sexual desire is non-transferable: to the person wanting Jane it is absurd to say ‘take Elizabeth, she will do just as well’; for what he wants to do is an action in which Jane is a constituent, and not just an instrument. True, Elizabeth could be substituted for Jane, as Leah was substituted for Rachel in the Old Testament story of Jacob’s marriage (Gen. 29.21-28). But Jacob’s desire was not transferred to Leah: he simply made a mistake, believing her to be Rachel. It is true too that you can desire more than one person, or move promiscuously from one person to the next. But there is a deep difference between orgiastic sex, in which the other is relevant only as a means, and serial seduction, in which the inter-personal intentionality of desire is maintained in truncated form. Consider Don Juan. The essence of his personality is seduction, and seducing means eliciting consent, through representing your own consuming interest in doing so. Don Juan is seductive because he feels passion for every woman he meets, and yet his passion is not transferable. It would be absurd to break into his seduction of Zerlina (in the version that we owe to Da Ponte and Mozart) with the announcement ‘take this one, she will do just as well’ (hence the pathos of Donna Elvira’s interruption). This point is made clear by Casanova in his Memoirs, in which his intense and interrogatory desire singles out each object in turn for the very person that she is, and for whom no other could possibly be a substitute – which is why Casanova was irresistible. If we thought of desire merely as a kind of hunger, satisfied now by this human burger, now by that, it would make sense to think of it as transferable. But, as I have suggested, even in the pathological cases like those of Don Juan and Casanova, it is the interest in the other that is the intentional heart of desire – and in the other as an embodied person, with a unique subjectivity that defines his or her point of view.

In a once widely read book, Eros and Agape, the Swedish Protestant theologian Anders Nygren made a radical distinction between erotic love, which is motivated by its object, and the Christian love commended by St Paul in the first letter to the Corinthians, ch. 13, which is motivated by God. Greek distinguishes the two as eros and agape, we as romantic love and neighbour-love. And a great change came over the world, in Nygren’s view, when agape replaced eros, as the raw material for the love of God. In Plato eros arises in a god-like way – that is to say, as an external and invading force, which overwhelms the psyche. But it ascends like a fire, and carries the subject heavenward, to the realm of the forms which is the kingdom of God. St Paul, by contrast, emphasizes agape, which comes to us from God, rather than raising us to him. The downward turning love of the almighty fills us with gratitude, and we reciprocate by spreading it outwards to our neighbours here on earth.

It would certainly be a mistake to confound eros and agape. Sexual love is not in itself a benefit conferred on the target: it may well be an affliction. Sexual love desires to possess, and usually to possess exclusively – or at least with an alert distrust of rivals. Sexual love can be cruel and full of anger; it has an ambivalent relation to moral virtue, and in certain forms – such as that described by Jean Genet in Le Journal du voleur and Nôtre Dame des fleurs – is inspired and excited by vice. It makes massive and unfair discriminations between the beautiful and the ugly, the strong and the weak, the young and the old. It is jealous, and cannot rejoice in the good things given by a rival. A person can murder the object of erotic love as Othello did, and when people fall in love they are aware that they are embarking on a path that is as much a threat to the social order as a natural fruit of it. Hence lovers are furtive; they conceal their feelings, knowing that the world is as likely to be angered as pleased by the sight of their attachment.16

None of those things is true of agape (charity), and no society could be founded on erotic love as a society might be founded on the love of neighbour. Hence eros is a danger: it is a force that undermines trust as much as it builds trust, and the greatest danger is that it might become detached entirely from inter-personal relations and returned to its animal origins. This is what Plato feared, and why he developed his theory of what we now know as Platonic love – maybe the most influential psychological theory in history. For Plato the physical urge must be overcome, so that the desire directed to the beautiful boy can be redirected to its proper object, which is the form of the beautiful itself.

Plato’s mistake was to think that normal sexual desire is directed towards the beautiful body, rather than towards the embodied subject. The solution to the problem of desire is not to overcome it, but to ensure that it retains its personal focus. A society based on agape alone is all very well, but it will not reproduce itself: nor will it produce the crucial relation – that between parent and child – which is the basis on which we can begin to understand our relation to God. Hence the redemption of the erotic lies at the heart of every viable social order – a fact well understood by traditional religions, all of which see sexual union as a ‘rite of passage’ in which society as a whole is involved, and which brings about an existential change in those whom it joins. This existential change requires a blessing, so as to be lifted from the realm of mutual appetite and remade as a spiritual union.

On the Cathedral of Reims there is affixed the sculpture of an angel, Figure 9, whose smile is intended to represent the love of God for men – the downward-tending, all comprehending love of agape. The sculptor has tried to represent the kind of existential support that we receive, on the Christian view, from God. He wishes to display the essence of love as Aquinas described it – the willing of another’s good.17 In the Thomist view love and friendship are to be understood as endorsements – ways of saying to another that ‘your being is my desire’. For this very reason, however, the smile on the angel’s face makes us uncomfortable. It is not the tender smile, the smile of the flesh, that one lover confers on another or that a mother confers on her child. It has a willed and abstract quality. This smile has not been ‘called forth’ onto the angel’s face by the particular person who is its object, for agape makes no distinctions, and may have no particular person in mind. Hence the smile has a double aspect: now it seems deliberate and therefore false, now involuntary and therefore replete with unearthly benevolence.

Figure 9. Reims Cathedral: Smiling Angel.

There is a truth in Aquinas’s view of love, that it involves willing the other’s good. But only some kinds of love are like that. Erotic love may desire the non-being of its object just as much as the being – something that we surely did not need Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde to show us. If I feel erotic love for another, I endorse her being for my sake as much as for hers. And the circumstances might arise in which my endorsement is withdrawn: like Othello, I might, in a passion of jealousy, seek her destruction. If I feel neighbour love for her, then my endorsement is entirely for her sake. It is unconditional in a way that erotic love can never be. Yet more unconditional, of course, is the love than shines in the old face of Rembrandt’s mother, who quietly and unassumingly makes a gift of herself to her son. The angel is not making a gift of himself: he is relaying the love of God. And although Christians believe that God also made a gift of himself, through Christ, this is a peculiarity of the Christian religion that is not reflected in the account of God’s love that we are given in the other Abrahamic faiths.

On one Christian understanding marriage is a sacrament – which means a union forged in the presence of God. And the purpose of the sacrament is to incorporate eros into the world of agape – to ensure that the face of the lover can still be turned to the world of others. Human societies differ in the way that they manage this, and some don’t even attempt it. But the purpose, where it exists, is everywhere the same: to ensure that the private face of the lover can at a moment become the public face of the citizen, or the outgoing face of the friend. Hence where marriage is not regarded as a sacrament, but merely as a contract between the husband and the parents of the bride, the face of the wife often remains hidden after marriage: marriage does nothing to lift her from the private to the public forms of love. That is the deep explanation of the burqa: it is a way of underlining the exclusion of women from the public sphere. They can appear there as a bundle of clothing, but never as a face: to be fully a person the woman must retreat into the private sphere, where eros, rather than agape, is sovereign.

The Thomistic idea of love, as willing the being and the flourishing of another, assumes a kind of existential separation between the lover and the beloved. I will your being by willing you to be other than me. In erotic love, however, there is an existential tie: the partners are bound up in each other (as we say ‘involved’), and this is an impediment to the attitude described by St Thomas. I do not will my lover to be wholly other than me, and I am not ‘happy for him’, as I am happy for others when they obtain something that they desire. And this is a partial explanation of the fact noted earlier, that lovers do not look at each other, but look into each other, and search the eyes and face of the beloved for the thing to which they seek to be united (and with which they can never really be united, since it is not a thing but a perspective, defined for all eternity as other than mine). C. S. Lewis puts the point nicely with his remark that friends are side by side, while lovers are face to face.18

Perhaps that goes some way towards explaining why it is that the great mystics and religious poets, when they endeavour to describe the love that the soul has for God, almost always follow Plato’s example, and take erotic love as their analogical base. This is true of St John of the Cross, of St Teresa of Avila, of Rumi and Hafiz. For the love of God is also an acknowledgement of total existential dependence, of the nothingness of my being until completed by him. Maybe his love coming down to me and through me to my fellow men is agape. But mine that aspires to him, and seeks him out in utter servitude, is more like eros, a condition of existential need. In the extreme forms of ecstasy, whether religious or sexual, the face is in fact eclipsed, the self utterly expelled from it, wandering as it were outside the body, and this is what we see in the face of St Teresa as Bernini depicted her, Figure 10. This is a face no longer inhabited by the self, like a place abandoned and falling into ruin.

In conclusion, it is appropriate to say something about the destiny of the face, in the world that we have entered – a world in which eros is being rapidly detached from inter-personal commitments and redesigned as a commodity. The first victim of this process is the face, which has to be subdued to the rule of the body, to be shown as overcome, wiped out or spat upon. The underlying tendency of erotic images in our time is to present the body as the focus and meaning of desire, the place where it all occurs, in the momentary spasm of sensual pleasure of which the soul is at best a spectator, and no part of the game. In pornography the face has no role to play, other than to be subjected to the empire of the body. Kisses are of no significance, and eyes look nowhere since they are searching for nothing beyond the present pleasure. All this amounts to a marginalization, indeed a kind of desecration, of the human face. And this desecration of the face is also a cancelling out of the subject. Sex, in the pornographic culture, is not a relation between subjects but a relation between objects. And anything that might enter to impede that conception of the sexual act – the face in particular – must be veiled, marred or spat upon, as an unwelcome intrusion of judgement into a sphere where everything goes. All this is anticipated in the pornographic novel, Histoire d’O, in which enslaved and imprisoned women are instructed to ignore the identity of the men who enjoy them, to submit their faces to the penis, and to be defaced by it.19

Figure 10. Bernini: St Teresa in Ecstasy.

A parallel development can be witnessed in the world of sex idols. Fashion models and pop stars tend to display faces that are withdrawn, scowling and closed. Little or nothing is given through their faces, which offer no invitation to love or companionship. The function of the fashion-model’s face is to put the body on display; the face is simply one of the body’s attractions, with no special role to play as a focus of another’s interest. It is characterized by an almost metaphysical vacancy, as though there is no soul inside, but only, as Henry James once wrote, a dead kitten and a ball of string. How we have arrived at this point is a deep question that I must here pass over. But one thing is certain, which is that things were not always so. Sex symbols and sex idols have always existed. But seldom before have they been faceless.

One of the most famous of those symbols, Simonetta Vespucci, mistress of Lorenzo da Medici, so captured the heart of Botticelli that he used her as the model for his great painting of the Birth of Venus (Figure 11). In the central figure the body has no meaning other than the diffusion and outgrowth of the soul that dreams in the face – anatomically it is wholly deformed, and a girl who actually looked like this would have no chance in a modern fashion parade. Botticelli is presenting us with the true, Platonic eros, as he saw it – the face that shines with a light that is not of this world, and which invites us to transcend our appetites and to aspire to that higher realm where we are united to the forms – Plato’s version of a world in which the only individuals are souls. Hence the body of Botticelli’s Venus is subservient to the face, a kind of caricature of the female anatomy which nevertheless takes its meaning from the holy invitation that we read in the eyes above.

Figure 11. Botticelli: Birth of Venus (detail).

Botticelli’s Venus is not a sex-object, but a sex-subject. The intrusion of the sex-object into art can be already witnessed in the salon art of nineteenth-century France. Witness Bouguereau’s brilliantly accomplished, Ingres-inspired and entirely saccharine Birth of Venus, in which vapid sensual faces stare vacantly at the goddess, as she turns her face from the spectator in order to sniff her freshly shaven armpit and to toy narcisistically with her hair (Figure 12). It would be unfair to dismiss this painting as pornographic. But there is no subject, only a void, within this Venus of flesh.

Botticelli’s great picture reminds us that the human face is to be understood in quite another way from the body-parts of an animal. Animals do not see faces, since they cannot see that which organizes eyes, nose, mouth and brow as a face – namely the self, whose residence those features are. It is in part from our experience of the face that we understand our world as illuminated by freedom. The face is therefore not just an object among objects, and when people invite us to perceive it as such, in the manner of the fashion model and the pop star, they succeed only in defacing the human form. This defacing is something that we witness all around us, and it is also experienced – especially in its sexual application – as a desecration. In my view it is no accident that we are disposed to speak of desecration when it comes to sex. We can desecrate only what is sacred. And in describing the role of the face in inter-personal relations I have been taking the first steps towards a theory of the sacred.

Levinas writes of the face as the absolute obstacle to murder, the sight of which causes the assassin’s hand to drop. Would that Levinas’s remark were true. But there is a truth contained in it. Through the face the subject appears in our world, and it appears there haloed by prohibitions. It is untouchable, inviolable, consecrated. It is not to be treated as an object, or to be thrown into the great computer and calculated away. Levinas wrote in torment, thinking of the murder of his own friends and family in the holocaust. And it is surely an apt description of the genocides of the twentieth century that they proceeded as they did only because subjects were first reduced to objects, so that all faces disappeared. That was the work of the concentration camp, and it is a work that has been described for all time by Primo Levi, Solzhenitsyn and the angelic Nijole Sadunaite – people who kept their faces, even in face of the all-defacing machine.

Figure 12. Bouguereau: Birth of Venus.

Nobody could say that the growth of the pornographic culture is a crime comparable to the crimes described by those writers, though, like those crimes, it is a crime against humanity.20 Nevertheless pornography has moved of its own accord to that first stage on the road to desecration – the stage of objectification, in which the face disappears, and the human being disintegrates into an assemblage of body parts. My own view is that we should see this as a warning. What to do about it, and what it means for us, are questions to which I return. But my remarks will only make proper sense, I think, if I move on to consider another kind of face against which the spirit of desecration is currently active: the face of the earth, as we humans have built it.

Notes

Humanism of the Other, trans. Nidra Poller, Chicago, University of Illinois Press, 2003, p. 44. | |

The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, 1873. | |

H. P. Grice, ‘Meaning’, The Philosophical Review, 66, 1957, 377–88. | |

See ScienceDaily, May 19, 2009, for the case of mockingbirds. Corvids (crows, magpies, jackdaws etc.) are well known for their ability to recognize individuals belonging to other species than their own. | |

This was shown in a series of experiments by G. G. Gallup in 1970. See G. G. Gallup Jr, ‘Chimpanzees: Self-recognition’, Science, 167, 86–7. Since then several other species have been shown to pass the ‘mirror test’, notably dolphins. Researchers have often inferred from this that such animals therefore have the sense, and even the concept, of self. This inference is not licensed by the evidence, however. | |

Si se non noverit, Ovid, Metamorphoses, III, 348. | |

The Phenomenology of Perception, 1945, trans. Colin Smith, London, Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1962. See also the excellent essay on our upright posture in Erwin Straus, Phenomenological Psychology, New York, Basic Books, 1966, and that by Raymond Tallis on the hand: The Hand: A Philosophical Enquiry into Human Being, Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, 2003. | |

Leon Kass, The Hungry Soul: Eating and the Perfecting of Our Nature, New York, Simon and Schuster, 1994; Raymond Tallis, Hunger, London, Acumen, 2008. | |

L’Être et le néant: Essai d’ontologie phénoménologique, Paris, Gallimard, 1943, Book III, Chapter 3. I discuss Sartre’s views in Sexual Desire, London, Weidenfeld, and New York, Free Press, 1986, pp. 120–5. | |

For pertinent discussion see Helmuth Plessner, Laughing and Crying: A Study of the Limits of Human Behavior, trans. James Spencer Churchill and Marjorie Grene, Evanston, Northwestern University Press, 1970, and F. H. Buckley, The Morality of Laughter, Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press, 2003. | |

There are conflicting etymologies: some say the word comes from Latin per-sonare, to sound through, others that the root is Etruscan, deriving from the cult of Persephone, who was the principal subject of the Etruscan theatre, where she had a role resembling that of Dionysus in the Attic theatre. | |

Sir Ernest Barker, introduction to Otto Gierke, Natural Law and the Theory of Society 1500–1800, trans. Barker, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1934, p. lxxi. | |

James H. Johnson, Venice Incognito: Masks in the Serene Republic, Berkeley, University of California Press, 2011, p. 128. | |

We owe the word ‘carnivalesque’, used to describe a comprehensive attitude to reality, to Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World, trans. Hélène Iswolsky, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1993. | |

I have defended this point at length in Sexual Desire: A Moral Philosophy of the Erotic, op. cit. The notion of the ‘embodied subject’ is also fundamental to the analysis of perception given by Merleau-Ponty. | |

Schopenhauer makes much of this point in the essay on sexual love, in The World as Will and Representation, vol. 2. | |

Summa Theologiae, 2a 2ae, qqs 25–8. | |

The Four Loves, London, Harvest Books, 1960. | |

Anon. (Anne Desclos) Histoire d’O, Paris, Pauvert, 1954. | |

How would I justify that charge? See Donna M. Hughes and James R. Stoner (eds), The Social Costs of Pornography: A Collection of Papers, Princeton, Witherspoon Institute, 2010. |