Gannets rain down on tight shoals of sardines, forced to the surface by sharks, seals and dolphins.

Thousands of predators pursue the all-you-can-eat sardine buffet.

Every midwinter, millions of sardines take advantage of a tongue of cold water flickering up KwaZulu-Natal’s subtropical coast.

Lured from the cold Cape waters by the apparent expansion of their coldwater habitat, 30 000 tons of them squeeze close to the shore on a shallow continental shelf, and turn into a moving all-you-can-eat buffet.

Gannets, albatrosses and cormorants rain down on tight shoals panicked and forced to the surface by sharks, seals and dolphins. Following them are the predatory fish such as shad, Cape salmon, garrick, yellowtail and kob. Dolphins often use the opportunity to wean their calves and to gorge on sardines, rebuilding their fat reserves.

Sometimes even killer whales can be seen chasing down the bounty. Fast swimming Bryde’s and sei whales also come to gorge themselves. Divers rave about the experience.

From the air, the shoals look like kilometre after kilometre of enormous black oil slicks, the lighter grey of the sharks wading into the mass, and the dolphins rounding up sardines, like sheepdogs.

National Geographic photographer David Doubilet, who has documented sea life all over the world, calls South Africa’s sardine run “one of the most amazing pulses of life in the world’s oceans”, a phenomenon every bit as dramatic as the migrations of the African savanna. Tourism touts call it “the greatest shoal on Earth”.

It’s usually the predators, or sometimes the current, that forces the sardines to beach in silver waves. Television cameras capture the event most years, a glittering haul carried away in women’s petticoats, little boys’ T-shirts, beach buckets, shopping bags and milk crates in feverish scenes of ecstatic bounty. It’s the “Rainbow Nation united in harvest”, as National Geographic writer Kennedy Warne once put it. – Julie

A traditional healer presides over a cleansing ceremony on a Durban beach.

If the Durban township of KwaMashu had been London, Bheki Biyela would have a sign out on Bond Street, saying “By Appointment To Her Royal Majesty”. As a supplier of traditional garb to the Zulu Royal House, he is known as one of the finest Zulu tailors in the country.

Outside his modest shack is a serval skin, stretched out on a rack. Inside Bheki’s place is a workroom and a bedroom – and little else. A stout Zulu man enters with the air of a regular customer and admires himself in a leopard-skin mantle – usually reserved for royalty. Three women who have seen our parked vehicle come by to show off their new isixolo, modern and lightweight versions of the wide red headdress worn by Zulu matrons.

Bheki – who has accepted us because we are in the company of a mutual friend (and guide for today) called Dave Charles – displays the striking new trend that has swept through the world of Zulu traditional garb: black-and-white suedette patterns with coloured car reflectors inset. Worn with catskin.

Along Musa Road in KwaMashu is a fruit stall festooned with dozens of fine bananas. Here we meet the bubbling Petros Mkhwanazi, former boxing announcer for Radio Zulu and future guest house entrepreneur. Once Dave has done the introductions in his fluid, sonorous Zulu, Petros takes us into his guest room, adorned with Zulu pin-up girls, boxing greats, two dangling weaver’s nests and a row of ancient, crumbling South African banknotes.

“I know, I know,” he says, laughing. “I once buried that money to keep it safe.”

Into this tiny 2x3-metre room Petros has packed a world of comforts: a bed, a television set, a stove and a chair. The en suite bathroom is basic, and I fear none but the bravest of travellers would book in at Chez Mkhwanazi. And how much would Petros charge for a night at his place?

The isiXolo headdress, worn by married Zulu women, has been updated to a modern, lightweight version.

“Thirty rands. No, make that thirty five ...”

We leave KwaMashu and enter Durban from the north, passing fabric shops and the venerable Lion Match factory, stopping at the disused railway station in Umgeni Road. This is where Zulu women rule. They are mostly rural women weavers who trek in for a few weeks to sell their wares. They stay somewhere in the back of the building and each morning they set up shop on the sidewalk, selling sleeping mats, black clay pots and Zulu cutlery.

Dave Charles asks the women if they are safe here on Umgeni Road. Are they not worried that men will rob them?

“Let them come”, one says defiantly. “Then they will see what we do to them ...”

Next stop is the Dalton Road Skin Dealers, a hive of industry.

An eccentrically rendered version of the Lion Match icon.

Women at Durban’s muthi market hack up medicinal plants.

This is the second economy of South Africa, Africa-to-Africa at full throttle.

Zulu shield maker, Kay Bhengu, in Dalton Road, Durban.

Durban’s streets are alive with colour and commerce.

Zulu radio blares out from the stalls, which double as bedrooms and shops for the workmen inside. They are making spears, knobkerries, drums, shields and the entire array of traditional Zulu paraphernalia you see the warriors wearing on TV at special occasions.

Here we find a powerful, strong-featured man called Kay Bhengu. He makes everything from beautiful cowhide shields to the nut-like object – the umncedo – worn at the end of a warrior’s penis. Dave provides a little light background: “In the old days, a Zulu man could be considered fully dressed wearing only this little widget fitted onto his member. It is said that when King Shaka berated his advisors, all their umncedos would drop off at the same time ...”

Our last stop of the morning is the Victoria Street Muthi Market, a sprawling outdoor display on a bridge overpass with the Durban skyline in the background. This is the second economy of South Africa, Africa-to-Africa at full throttle. More than 80 per cent of all South Africans use traditional medicine at some time in their lives. Hundreds of metres of stalls are bunched up next to each other selling powders, roots, barks, shells, animal heads, skins of every description, sea beans, wings, feathers and other body parts – each with a specific medicinal purpose.

I catch up with Dave Charles, who is joyously chatting with a woman about one of her potions. They are inspecting some “Zulu Viagra”, and it turns into a crowd-stopping passage involving ribald movements of hands, raised eyebrows and much laughter. Everyone passing by has something to add to the conversation, and by the way they leer at me I can see Dave is setting me up for a big sale. I’m right. The potions lady scoops together twigs and fine brown powder into some newspaper wrapping and informs me, via Mr Charles, “One tablespoon if you’re brave, stirred into a glass of milk or a cup of soup. But make sure there’s a woman in your arms already, because this thing, it works fast”. – Chris

Michael Oberholzer is the self-appointed guardian of Thompson’s Tidal Pool.

Before dawn every day, regardless of the weather, Michael O slips on his Zulu thousand-miler sandals (with carved-in “swoosh”) and walks the eighteen minutes from his apartment to the sea.

Here, in the super-rich coastal town of Ballito, Michael O has found a shrine. It comes in the form of Thompson’s Tidal Pool down by the beach. Michael has become the custodian of the tidal pool, which locals often refer to as Charlie’s Pool because it was built by one of the first settlers there, Charles de Charmoy, his son Roland and their staff, in 1962.

In its own way, the tidal pool tries to look after Michael, too. Before he swims, Michael goes to the rocks at the ocean side of the pool and just watches the restless waves for twenty minutes. Then he inserts earplugs (swimmer’s ear is the occupational hazard down here), dons his yellow goggles and announces to us, “Welcome to my office”.

Standing waist deep in the tidal pool, with the deep green Art Deco change rooms in the background, Michael smiles as the hardy little blacktail fish come to nibble dead skin from his legs. Recently, when he and his partner Harriet were away for a short while, his tidal pool was drained so a leak could be fixed.

“Every single bit of life in the pool vanished,” Michael says. “They ate everything.” But all is never lost. The neap tide is washing fresh seawater into the pool with each wave. And it seems the mud prawns – which help to purify the water – are on their way back. They have already punched tiny little blowholes in the sand at the bottom of the pool. Soon the other familiar forms of life – Michael’s Tidal Pool Club – will be able to return.

“Normally, you’d find sea cucumbers, an octopus, the prawns, more than forty varieties of fish and crabs here,” he says, preparing for his laps. “The triggerfish used to know me well. They swam underneath me in convoy. I think they recognised my stroke.”

He swims 17 laps around the pool in a deceptively slow but powerful crawl – freestyle. In ninety minutes he covers more than five kilometres. Another wave from the rising tide washes into the pool.

Some years ago, he came down here on a break from a highly pressurised job in gold mining.

“Gazing at the sea and swimming in the pool every day made me feel better,” he says. “At the pool, things became simple. There was no one to boss me around – and there was no one to retrench. I suddenly realised I could not remember when last I had seen the stars, or the sunrise. I remembered my dad, who had bought a seaside house for his retirement. He died before he could live there.”

Michael O – at the tender age of 49 – took early retirement and went back to his tidal pool, permanently. – Chris

The elegant lines of the changing rooms at Thompson’s Pool.

As far as he can, Michael helps to protect this tidal pool and the surrounding area.

Water-dependent species like reedbuck, hippos and saddle-billed storks are extending their ranges at St Lucia as the pines vanish and the wetland-rich coastal grasslands return.

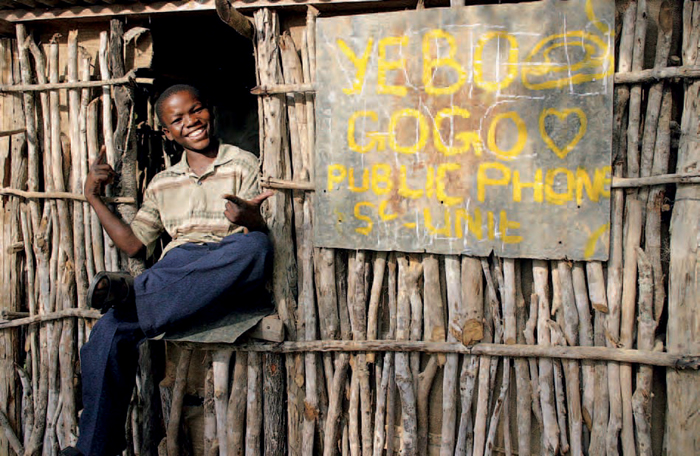

The newly-created KwaJobe road has brought entrepreneurial opportunities to this area.

Centuries, or maybe millennia, ago, the first leatherback turtle misguidedly laid her eggs in the titanium-rich beaches off what is now the Greater St Lucia Marine Sanctuary.

Turtles are not supposed to lay eggs this far south. The sand below the Tropic of Capricorn does not hold its heat long enough at night to act as an incubator.

But St Lucia’s beach sand is not conventional quartzite. It is laden with metallic titanium, or ilmenite, which conducts and retains heat and moisture. The eggs hatched successfully, and started something of a turtle trend.

If Rio Tinto Zinc’s bid to mine ilmenite here in the early 1990s had been given the go-ahead, this natural incubator for turtles would have been destroyed. Eventually, there would have been no more summer nocturnal tours to watch these “big mamas” slowly hauling themselves up the beach to lay eggs.

But here we are, fourteen years later, and wildlife specialist guide Kian Barker has us out on the sanctuary’s beaches to look for loggerheads and leatherbacks.

The leatherbacks can weigh more than a ton, and as they lumber onto the sands it’s hard to imagine them scooting through the ocean at 100 kilometres per hour. But when you have a hungry tiger shark or mako on your tail, a dash of speed is always the answer. Then they dive into the dark, cold oceanic waters, where sharks are not equipped to follow them.

“The leatherbacks hover offshore down in Leven Canyon or even deeper, over the continental shelf, until dark,” says Kian, as he drives us north from the town of St Lucia. “A female will come out and lay more than a thousand eggs over about a dozen visits in the space of three months. After that, you won’t see her again for as long as seven years. Some of them go off to the upwellings on our West Coast, others will head towards the East Indian oceans or even as far as the Pacific.”

Just north of Cape Vidal, we find fresh tracks of a loggerhead. This old turtle is heading for a spot just below the normally packed carpark, where the ocean’s roar is often smothered by loud music. Tonight, there is no sound beyond that of the waves.

Kian keeps us all at bay until the turtle has gone into an “egg trance” and our presence matters no longer.

“I call it a genetic epidural,” says Kian. “Nature just switches off the senses and instinct takes over. Everything slows down. It’s a bit like an old Windows ’92 program. Once a certain action (like digging) ends, there’s a couple of minutes’ break, and then the next one (in this case, egg laying) starts. Always the same – and always very slow and methodical.”

We kneel in reverence behind the loggerhead mother. It is a perfect night, with only a slight sea breeze. Here before us is a seaborne creature the size of a modest coffee table digging a hole in the earth for her eggs, her flippers flicking sand away in a 200-million-year-old ritual.

The eggs begin to pop out in quick succession. The mom has finished. You can see it costs a turtle an enormous amount of energy to crawl out of the buoyant sea, submit to exhausting gravity, and dig a careful hole for her babies.

As we drive away, we see the waiting ghost crabs skittering away in the headlights. In a few months, the tiny turtle babies will have to run the gauntlet of these ravenous creatures, pale death riding on eight hydraulically operated legs.

It was not the potential loss of turtles that eventually swayed politicians to reject mining in favour of retaining natural beauty in the mid-1990s. Nor was it St Lucia’s extraordinary “sense of place”, invoked by environmentalists who energetically opposed mining because it would destroy a fragile beauty and biodiversity unparalleled in South Africa.

It wasn’t even because renowned conservationist Dr Ian Player threatened to lie down naked in front of the bulldozers.

The reason came down to sustainable jobs. Ecotourism promised to employ three times as many people directly, and thousands more indirectly, as dune mining, which offered only 313 lifetime jobs.

Like the Wild Coast, northern KwaZulu-Natal is rich in natural beauty but not in prosperity.

Once mining was rejected in 1994, conservationists were put under massive pressure to deliver the promised jobs and benefits to local people, but, despite the urgency, matters stagnated over four years.

It was only in late 1998 that things really started moving.

The man put in charge of the Greater St Lucia Wetland Park Authority was Andrew Zaloumis, a community worker who had lived in the wilds up near Mozambique’s border for years.

Andrew and his team had to consolidate 16 separate parcels of land into one park and prepare it for linkage with wilderness areas in both Swaziland and Mozambique.

Turtle females (loggerheads and leatherbacks) drag themselves up the beach north of Lake St Lucia to lay their eggs in carefully dug holes – a 200-million-year-old ritual.

Andrew Zaloumis (far right) and the Bhangazi elders, who have won a land claim and opted to develop a small peninsula for tourism, walking across the drought-stricken Lake.

In 1999, the Greater St Lucia Wetland Park was listed as South Africa’s first World Heritage Site. But even though it had been designated a natural treasure of great importance, the park was still very much a work in progress, something the UNESCO committee found refreshingly unconventional.

Pristine areas usually get the World Heritage nod. Here, on the other hand, was a place so riddled with alien pine trees that Australian delegates to the 2003 World Parks Congress in Durban teasingly referred to it as “that Swiss Alpine World Heritage Site”. Given the chance, those Aussies would probably have staged a mock cheese fondue on the Eastern Shores just to drive the point home.

But by 2005, six million pines had been chopped down – with more than seven thousand hectares of plantation still awaiting clearance, providing jobs for part of a pool of 4 500 newly employed people. One of the greats of South African conservation, Dr Ian Player (brother of golfer Gary Player) said a circle of his life had now been completed – he was witness to the 1953 forced removals to make way for these “soldier trees”.

Another poignant circle was being closed – Andrew was helping to shape the country’s great new national park that his late father Nolly, along with Dr Player and many others, had helped to save from mining.

The water-thirsty pines were barely out of the ground and their stumps burnt before marshlands began to reappear. Water-dependent species such as reedbuck, waterbuck and saddle-billed stork were extending their ranges as the pines vanished and the wetland-dappled coastal grasslands returned. A family of hippo came to enquire about real estate in the area – and were accommodated in a reconstituted lakelet.

This vast 380 000-hectare expanse of lake, islands and estuary not only incorporates an astonishing variety of habitats, but nearly half a million local inhabitants as well. Zaloumis and Co. had to think out of the box and help provide a living for as many as possible. The dune-mining option will probably always hang like the Sword of Damocles over Greater St Lucia.

But already there are more tangible benefits than recuperating coastlands. Ecologically sensitive roads are linking previously isolated communities to markets, medical centres and schools. Lake St Lucia is malaria-free for the first time in human memory. The last elephant in the St Lucia system had been shot in 1916. In 2001, elephants were brought back to the Eastern Shores.

Previously, the St Lucia complex was known to few holidaymakers. It was the diver’s den, the fisherman’s friend and a place where senior policemen could have a burnt-meat ball. Now, because of its World Heritage status, it has an international profile. Community-shared tourism is the way to go, and luxury lodges and backpacker camps stand shoulder to shoulder at carefully selected sites.

There are turtles and dolphins and whales to be watched, dune forests and beaches and rock pools to explore, birds and big game and belly safaris to absorb.

Not only can you fish and dive, but there are turtles and dolphins and whales to be watched, dune forests and beaches and rock pools to explore, birds and big game and belly safaris to absorb. Suddenly the whole St Lucia experience has blossomed into dozens of new possibilities. Different kinds of tourists – both local and international – are arriving.

With each new inspiration comes a spurt of job opportunities for the local people.

But now Greater St Lucia is facing another challenge – a brutal drought, the worst in living memory. For five years now, rains have been stubbornly below average. Lake St Lucia has shrunk to a quarter of its normal size, and in parts is more saline than the sea. The biggest problem is the fact that the Mfolozi River has been separated from the lake by dredging. It is so damaged by sugar farming on the Mfolozi flats that the silt alone would deal a killing blow to life in the lake.

The only fresh water in the system is coming from the ancient dunes that were so nearly mined. They act like giant aquifers, trickling out rainwater that fell years ago. If not for them, there would already have been a massive ecological collapse. – Julie

Vervet monkeys thrive in the coastal forests.

The Gumede wives and some of his daughters are very proud of their crafts – the money they make has transformed their lives.

The road to Mtubatuba is a strip mall of tropical fruit, sweet with the smell of pineapple.

We are on our way to meet Majindi “Weekend” Gumede and his many wives, who have formed themselves into a highly productive cottage-industry unit. En route, we stop at a small river to watch the women driving fish with their reed fonya baskets. They wave back.

As we drive further, Bronwyn James tells us how local people are already benefiting from the formation of this extraordinary new tourism attraction – the Greater St Lucia Wetland Park.

Bronwyn is as tall as her title. She is head of the Social Economic and Environmental Unit (SEED), operating under the Greater St Lucia Wetlands Park Authority.

“Women in these areas have a strong tradition of craft and weaving, but they earn a pittance. Natural resources are also taking a beating. You only have to look at some of the magnificent meat platters: a whole tree is destroyed to make platters that sell for under a hundred rands.”

Bronwyn says they found the women had limited access to markets – mostly pension days, agricultural fairs and the roadside – and the products mostly looked the same, which drove down the price.

Clearly the goods had to become more diverse, with colours and shapes that would appeal to more lucrative markets.

One of the ways they did this was to recruit product developers, offering them learnerships. Sivuyile Piliso was one of these recruits, a funky young graduate in design from Port Elizabeth Technikon.

He had some catching up to do.

“I knew about fashions and colours, but I knew nothing about rural development and livelihoods, what is sustainable and what isn’t.”

For extra back up, Sivu and his colleagues are also mentored by Richard Sparks from Bright House and Marisa Fick-Jordaan from the BAT Centre in Durban.

The products also had to be made of renewable resources, in keeping with the Greater St Lucia Wetland Park’s conservation ethic.

Each group of about a dozen women make products specific to the area using available materials such as isikonko reeds, ilala palm frond and sisal. The magical ilala also makes a very potent, high-energy wine that gives a spring to the local step – and one helluva hangover to outsiders like us.

The basket weavers of the KwaJobe Road – new contracts have given them new hope.

Above left, and Below Weekend Gumede has 10 wives and 62 children. Thanks to the money from selling woven goods, his children are being sent to school.

Above right More than 400 women are now receiving a decent income from weaving baskets and mats – an opportunity created through the Greater St Lucia Wetland Park.

“There are about 400 women already creating baskets and mats, and just recently, Mr Price (a popular retailer) placed R120 000 worth of craft orders over two months,” she says. “This will probably increase the number of women employed, and boost earnings from this area.”

Carefully avoiding cattle and goats as they drink from rainwater puddles along the KwaJobe Road, we reach a small village in a clearing of trees where curious children peer out from behind huts.

A large bare-chested man with white hair and a beard greets us from where he sits in his doorway, watching the Zulu rain drop down in a gentle drizzle. This is Weekend Gumede, husband to 10 wives, father of 62 children. He is currently ill, we are told. We ask permission to take a photograph of him, he nods and we turn to the women under the trees.

The women arrange themselves and their goods in a photo-friendly semicircle. We are seated on chairs in front and handed umbrellas. But then the rain simply buckets down and we all decamp to someone’s bedroom, where the handwritten sign on the back of the wooden door reads “I love Christian No 1”.

When craft training began for the people of St Lucia in 2000, Bongi Gumede stepped forward, got the orders and recruited the rest of her family into the project. She was still the money administrator.

“Does a lot of it get handed over to Weekend?” we want to know.

This is greeted with a raucous round of laughter. Perish the thought.

“We don’t give the money to him,” she says. “But we do show him how much we’re making. And then sometimes we buy him something nice.”

These women’s lives – and those of their children – have changed immensely since they started earning money with their crafts. Suddenly, school fees and clothes and groceries can be paid for.

“It was difficult to earn money before,” they tell us. “We used to cultivate mealies and vegetables and we made traditional beer to sell in the villages nearby. But we got far less money than now. Also, many of our children did not go to school.”

Not one of the Gumede wives had a formal education. Before the “change”, their children would also have dropped out of the system early. Now all those of schoolgoing age are being educated, and their parents are planning to send them to university. Most of the working mothers now have cellphones, radios, wardrobes, beds and blankets. Many are building themselves brick houses. Bongi has bought herself a sewing machine. Power comes from car batteries. Outages? What outages?

Gugu Gumede is particularly proud of her new goat.

“You must keep a goat, for just in case,” she said. “You can always sell the kids.”

Sisters. Doing it for themselves. We walk over and say goodbye to Majindi “Weekend” Gumede, the luckiest guy in Zululand. – Julie

Canoe tourists enjoying the water of Kosi Bay.

After the unexpectedly vibrant little town of Manguzi, we head north for Kosi. The homesteads thin out and the trees grow taller. The sand is ever present.

At one spot, our gallant bakkie hesitates in deep sand and sinks, wheels spinning. Andrew Zaloumis shows me how to deflate tyres, activate difflock, keep one wheel on the grass and get through. He’s been here before.

We drive over a beautiful iron bridge that spans tea-coloured waters and clatters with the weight of our vehicles. This is where an erstwhile Environment Minister (Valli Moosa) had been controversially photographed skinny-dipping years before. I personally think all Environment Ministers could do with more skinny-dipping and less office-jockeying. But that’s just me.

We pull up at Hlalanathi (Stay With Us) Camp, which has a splendid view of Kosi Bay’s third lake, turning pewter in the overcast afternoon light. Amos Ngubane and his wife Maria welcome us.

Amos assisted the late activist and sociologist David Webster in his work up here from 1984 until 1989, when Webster was gunned down by apartheid cops in Troyeville, Jo’burg.

“I was in his house that day. I heard the shot outside,” said Amos. “My grief was great.”

Early the next morning, Jules and I discover the delights of a cold water bucket shower, have breakfast with the Zaloumis family and are picked up by Dr Scotty Kyle for a day on Kosi Bay.

In reality, Kosi Bay is a string of four lakes, linked with narrow channels, with the “first lake” opening onto the sea near South Africa’s border with Mozambique.

I have no trouble calling Scotty Kyle “The Laird of the Bay”. The doughty Scotsman (definitely not “dour”) has been here for more than a quarter of a century, keeping a watchful eye on the natural assets of Kosi Bay in his role as resource ecologist for the area.

We climb aboard his flat-bottomed sleigh-boat, Poch Mahon (a Celtic blessing, he cryptically assured us), and ride through choppy waters towards the fish traps.

“Fish traps have been here for centuries,” Scotty says loudly above the din of the outboard motor. “Portuguese shipwreck survivors noticed them five hundred years ago – but they probably go back to prehistoric times.”

The famous fish traps of Kosi Bay continued in the same old successful, sustainable manner until the mid-1990s, when the first waves of retrenched gold-miners came back home.

“The number of fish traps trebled in four years,” says Scotty. “And, as usual, human efficiency became nature’s enemy. The new guys started using nylon to tie the saplings together, closing the gaps and making them more effective. Which meant that the fingerlings were caught and not allowed to escape to breed and grow big.”

A fisherman with gillnets (which authorities are trying to limit) poles slowly across the third of Kosi’s four interlinked lakes.

The ancient fish trap system of Kosi Bay – the old ways are still the best ways.

It has taken Scotty Kyle many years of quiet negotiation with the local indunas to get most of them to return to the sustainable old methods, using rope made from the fibres of wild banana stems.

We chug up to where a well-built, senior man is busy with his traps and his spears. I want photographs.

“Maybe, maybe,” says the 72-year-old Amon Mkhize thoughtfully, “But, you know, there is nothing for nothing.”

We settle on a photo fee of R50 and I jump into the unexpectedly deep water, hoisting the rather expensive Canon 20D camera above my head just in time.

With Amon’s grinning face sticking out of Kosi Bay in front of his old-style fish traps, me dancing around in the warm waters, and Jules and Scotty bobbing about nearby in the boat, a good time is happening all around.

Amon Mkhize used to work in Jo’burg on the gold mines.

“But I was lucky,” he said. “I retired way back in 1985 – before they could push me.”

He catches king fish, rock salmon and crabs for the pot. Whatever is left, he sells to others. Why does he not use nylon in his traps?

“I use what my grandfather used,” he says. “I don’t like nylon. It doesn’t let the small fish escape.”

Scotty beams.

Jules and I spend our last night of the trip at the Turtle Shack at Bhanga Nek, with Andrew and his family. The sea roars in our ears; the cast and fetch of the waves rocks us to sleep.

On our way out the next morning, the bakkie falls deep into the soft sand once more. Everyone, including Grandma Molly, pitches in to help us out, bringing sticks and branches to put under the back wheels for traction. Even the Jack Russell puppy, Harry, comes running up with a couple of twigs in his mouth.

As we leave Kosi, finger grasses bobbing in the wind at the side of the road wave us goodbye. – Chris

Amon Mkhize, former miner, now full-time Kosi Bay fisherman, inspects his fish traps on an overcast day.

The banded mongoose leads a fruitful life in the wilds of Kosi Bay.

A male pied kingfisher on the hunt for lunch.