6

MILLION DOLLAR ELM

MILLION DOLLAR ELM

Even with the murders, they kept on coming, the greatest oil barons in the world. Every three months, at ten in the morning, these oilmen—including E. W. Marland and Bill Skelly and Harry Sinclair and Frank Phillips and his brothers—pulled in to the train station in Pawhuska, in their own luxurious railcars. The press would herald their approach with bulletins: “MILLIONAIRES’ SPECIAL” DUE TO ARRIVE; PAWHUSKA GIVES CITY OVER TO OIL MEN TODAY; MEN OF MILLIONS AWAIT PSYCHOLOGICAL MOMENT.

The barons came for the auction of Osage leases, an event that was held about four times a year and that was overseen by the Department of the Interior. One historian dubbed it the “Osage Monte Carlo.” Since the auctions had begun, in 1912, only a portion of Osage County’s vast underground reservation had been opened to drilling, while the bidding for a single lease, which typically covered a 160-acre tract, had skyrocketed. In 1923, the Daily Oklahoman said, “Brewster, the hero of the story, ‘Brewster’s Millions,’ was driven almost to nervous prostration in trying to spend $1,000,000 in one year. Had Brewster been in Oklahoma…he could have spent $1,000,000 with just one little nod of his head.”

In good weather, the auctions were held outdoors, on a hilltop in Pawhuska, in the shade of a large tree known as the Million Dollar Elm. Spectators would come from miles away. Ernest sometimes attended the events, and so did Mollie and other members of the tribe. “There is a touch of color in the audiences, too, for the Osage Indians…often are stoical but interested spectators,” the Associated Press reported, deploying the usual stereotypes. Others in the community—including prominent settlers like Hale and Mathis, the Big Hill Trading Company owner—took a keen interest in the auctions. The money flowing into the community from the oil boom had helped to build their businesses and to realize their once seemingly fantastical dreams of turning the raw prairie into a beacon of commerce.

![]() Frank Phillips (on bottom step) and other oilmen arrive in Osage territory in 1919. Credit 22

Frank Phillips (on bottom step) and other oilmen arrive in Osage territory in 1919. Credit 22

The auctioneer—a tall white man with thinning hair and a booming voice—would eventually step under the tree. He typically wore a gaudy striped shirt and a celluloid collar and a long flowing tie; a metal chain, connected to a timepiece, dangled from his pocket. He presided over all the Osage sales, and his moniker, Colonel, made him sound like a veteran of World War I. In fact, it was part of his christened name: Colonel Ellsworth E. Walters. A master showman, he urged bidders on with folksy sayings like “Come on boys, this old wildcat is liable to have a mess of kittens.”

![]() Colonel Walters conducting an auction under the Million Dollar Elm Credit 23

Colonel Walters conducting an auction under the Million Dollar Elm Credit 23

Because the least valued oil leases were offered first, the barons usually lingered in the back, leaving the initial bidding to upstarts. Jean Paul Getty, who attended several Osage auctions, recalled how one oil lease could change a man’s fate: “It was not unusual for a penniless wildcatter, down to his last bit and without cash or credit with which to buy more, to…bring in a well that made him a rich man.” At the same time, a wrong bid could lead to ruin: “Fortunes were being made—and lost—daily.”

The oilmen anxiously pored over geological maps and tried to glean intelligence about leases from men they employed as “rock hounds” and spies. After a break for lunch, the auction proceeded to the more valuable leases, and the crowd’s gaze inevitably turned toward the oil magnates, whose power rivaled, if not surpassed, that of the railroad and steel barons of the nineteenth century. Some of them had begun to use their clout to bend the course of history. In 1920, Sinclair, Marland, and other oilmen helped finance the successful presidential bid of Warren Harding. One oilman from Oklahoma told a friend that Harding’s nomination had cost him and his interests $1 million. But with Harding in the White House, a historian noted, “the oil men licked their chops.” Sinclair funneled, through the cover of a bogus company, more than $200,000 to the new secretary of the interior, Albert B. Fall; another oilman had his son deliver to the secretary $100,000 in a black bag.

In exchange, the secretary allowed the barons to tap the navy’s invaluable strategic oil reserves. Sinclair received an exclusive lease to a reserve in Wyoming, which, because of the shape of a sandstone rock near it, was known as Teapot Dome. The head of Standard Oil warned a former Harding campaign aide, “I understand the Interior Department is just about to close a contract to lease Teapot Dome, and all through the industry it smells….I do feel that you should tell the President that it smells.”

The illicit payoffs were as yet unknown to the public, and as the barons moved toward the front of the Million Dollar Elm, they were treated as princes of capitalism, the crowd parting before them. During the bidding, tensions among the magnates sometimes boiled over. Once, Frank Phillips and Bill Skelly began to fight, rolling on the ground like rabid racoons, while Sinclair nodded at Colonel and walked off triumphantly with the lease. A reporter said, “Veterans of the New York Stock Exchange have witnessed no more thrilling scramble of humanity than the struggling group of oil men of state and national repute throw themselves into the fray to get at the choice tracts.”

On January 18, 1923, five months after the murder of McBride, many of the big oilmen gathered for another auction. Because it was winter, they met in the Constantine Theater, in Pawhuska. Billed as “the finest building of its kind in Oklahoma,” the theater had Greek columns and murals and a necklace of lights around the stage. As usual, Colonel started with the less valued leases. “What am I bid?” he called out. “Remember, no tracts sold for less than five hundred dollars.”

A voice came out of the crowd: “Five hundred.”

“I’m bid five hundred,” Colonel boomed. “Who’ll make it six hundred? Five going to six. Five-six, five-six—thank you—six, now seven, six-now-sev’n…” Colonel paused, then yelled, “Sold to this gentleman for six hundred dollars.”

Throughout the day, bids for new tracts steadily grew in value: ten thousand…fifty thousand…a hundred thousand…

Colonel quipped, “Wall Street is waking up.”

Tract 13 sold for more than $600,000, to Sinclair.

Colonel took a deep breath. “Tract 14,” he said, which was in the middle of the rich Burbank field.

The crowd hushed. Then an unassuming voice rose from the middle of the room: “Half a million.” It was a representative from Gypsy Oil Company, an affiliate of Gulf Oil, who was sitting with a map spread on his knees, not looking up as he spoke.

“Who’ll make it six hundred thousand?” Colonel asked.

Colonel was known for his ability to detect even the slightest nod or gesture from bidders. At auctions, Frank Phillips and one of his brothers used almost imperceptible signals—a raised eyebrow or a flick of a cigar. Frank joked that his brother had once cost them $100,000 by swatting a fly.

Colonel knew his audience and pointed at a gray-haired man with an unlit cigar clamped between his teeth. He was representing a consortium of interests that included Frank Phillips and Skelly—the old adversaries now allies. The gray-haired man made an almost invisible nod.

“Seven hundred,” cried Colonel, quickly pointing to the first bidder. Another nod.

“Eight hundred,” Colonel said.

![]() Downtown Pawhuska in 1906, before the oil boom Credit 24

Downtown Pawhuska in 1906, before the oil boom Credit 24

![]() Pawhuska was transformed during the oil rush. Credit 25

Pawhuska was transformed during the oil rush. Credit 25

He returned to the first bidder, the man with the map, who said, “Nine hundred.”

Another nod from the gray-haired man with the unlit cigar. Colonel belted out the words: “One million dollars.”

Still, the bids kept climbing. “Eleven hundred thousand now twelve,” Colonel said. “Eleven—now twelve—now twelve.”

Finally, no one spoke. Colonel stared at the gray-haired man, who was still chewing on his unlit cigar. A reporter in the room remarked, “One wishes for more air.”

Colonel said, “This is Burbank, men. Don’t overlook your hands.”

No one moved or uttered a word.

“Sold!” Colonel shouted. “For one million one hundred thousand dollars.”

Each new auction seemed to surpass the previous one for the record of the highest single bid and the total of millions collected. One lease sold for nearly $2 million, while the highest total collected at an auction climbed to nearly $14 million. A reporter from Harper’s Monthly Magazine wrote, “Where will it end? Every time a new well is drilled the Indians are that much richer.” The reporter added, “The Osage Indians are becoming so rich that something will have to be done about it.”

A growing number of white Americans expressed alarm over the Osage’s wealth—outrage that was stoked by the press. Journalists told stories, often wildly embroidered, of Osage who discarded grand pianos on their lawns or replaced old cars with new ones after getting a flat tire. Travel magazine wrote, “The Osage Indian is today the prince of spendthrifts. Judged by his improvidence, the Prodigal Son was simply a frugal person with an inherent fondness for husks.” A letter to the editor in the Independent, a weekly magazine, echoed the sentiment, referring to the typical Osage as a good-for-nothing who had attained wealth “merely because the Government unfortunately located him upon oil land which we white folks have developed for him.” John Joseph Mathews bitterly recalled reporters “enjoying the bizarre impact of wealth on the Neolithic men, with the usual smugness and wisdom of the unlearned.”

The accounts rarely, if ever, mentioned that numerous Osage had skillfully invested their money or that some of the spending by the Osage might have reflected ancestral customs that linked grand displays of generosity with tribal stature. Certainly during the Roaring Twenties, a time marked by what F. Scott Fitzgerald called “the greatest, gaudiest spree in history,” the Osage were not alone in their profligacy. Marland, the oil baron who found the Burbank field, had built a twenty-two-room mansion in Ponca City, then abandoned it for an even bigger one. With an interior modeled after the fourteenth-century Palazzo Davanzati in Florence, the house had fifty-five rooms (including a ballroom with a gold-leaf ceiling and Waterford crystal chandeliers), twelve bathrooms, seven fireplaces, three kitchens, and an elevator lined with buffalo skin. The grounds contained a swimming pool and polo fields and a golf course and five lakes with islands. When questioned about this excess, Marland was unapologetic: “To me, the purpose of money was to buy, and to build. And that’s what I’ve done. And if that’s what they mean, then I’m guilty.” Yet in only a few years, he would be so broke that he couldn’t afford his lighting bill and had to vacate his mansion. After a stint in politics, he tried to discover another gusher but failed. His architect recalled, “The last time I saw him, I think he was just sitting on a nail keg of some kind out there northeast of town. It was raining and he had on a raincoat and rain hat but he was just sitting there kind of dejected. Two or three men were working his portable drilling rig and hoping they might find oil. So I just walked off with a lump in my throat and tears in my eyes.” Another famed oilman in Oklahoma quickly burned through $50 million and ended up destitute.

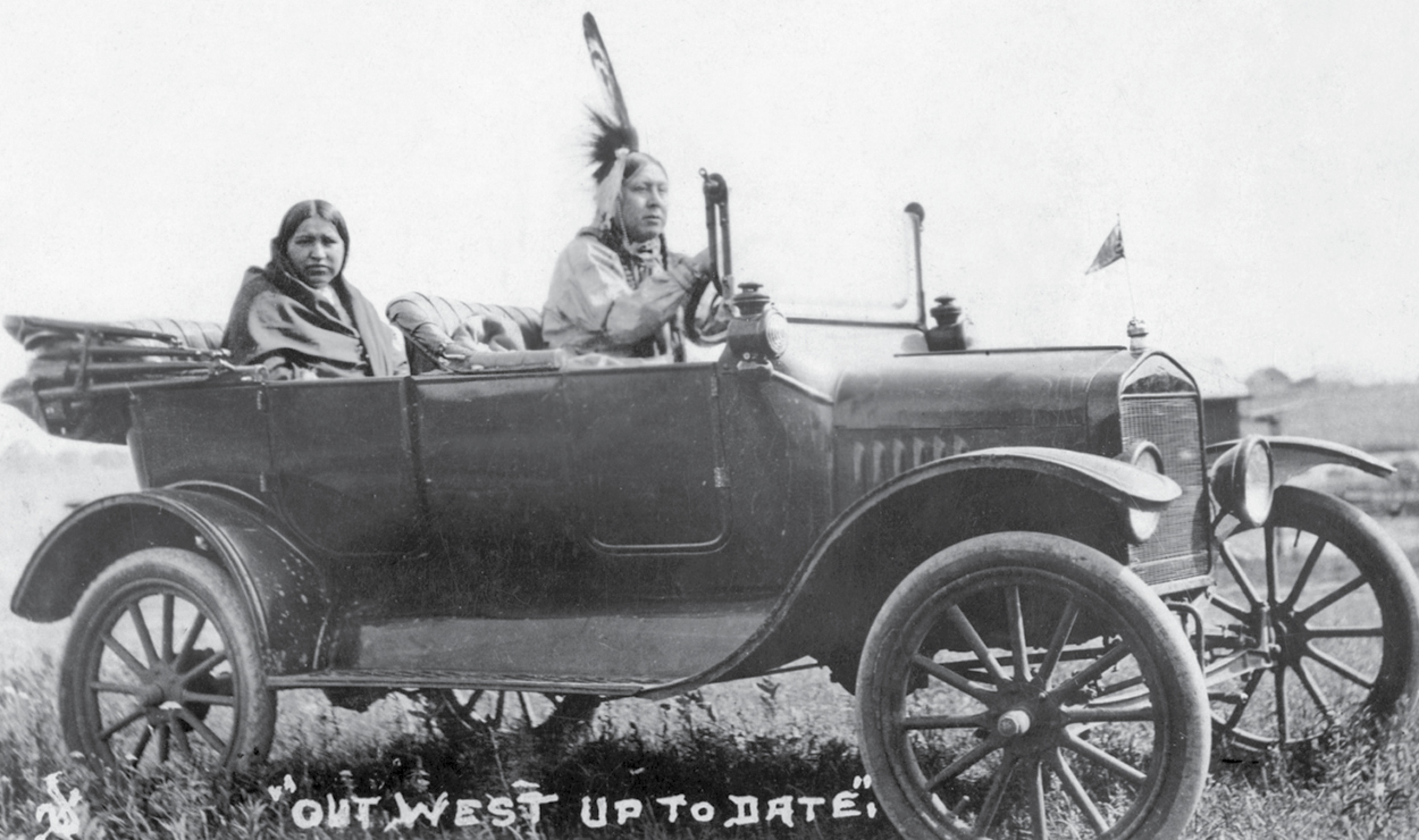

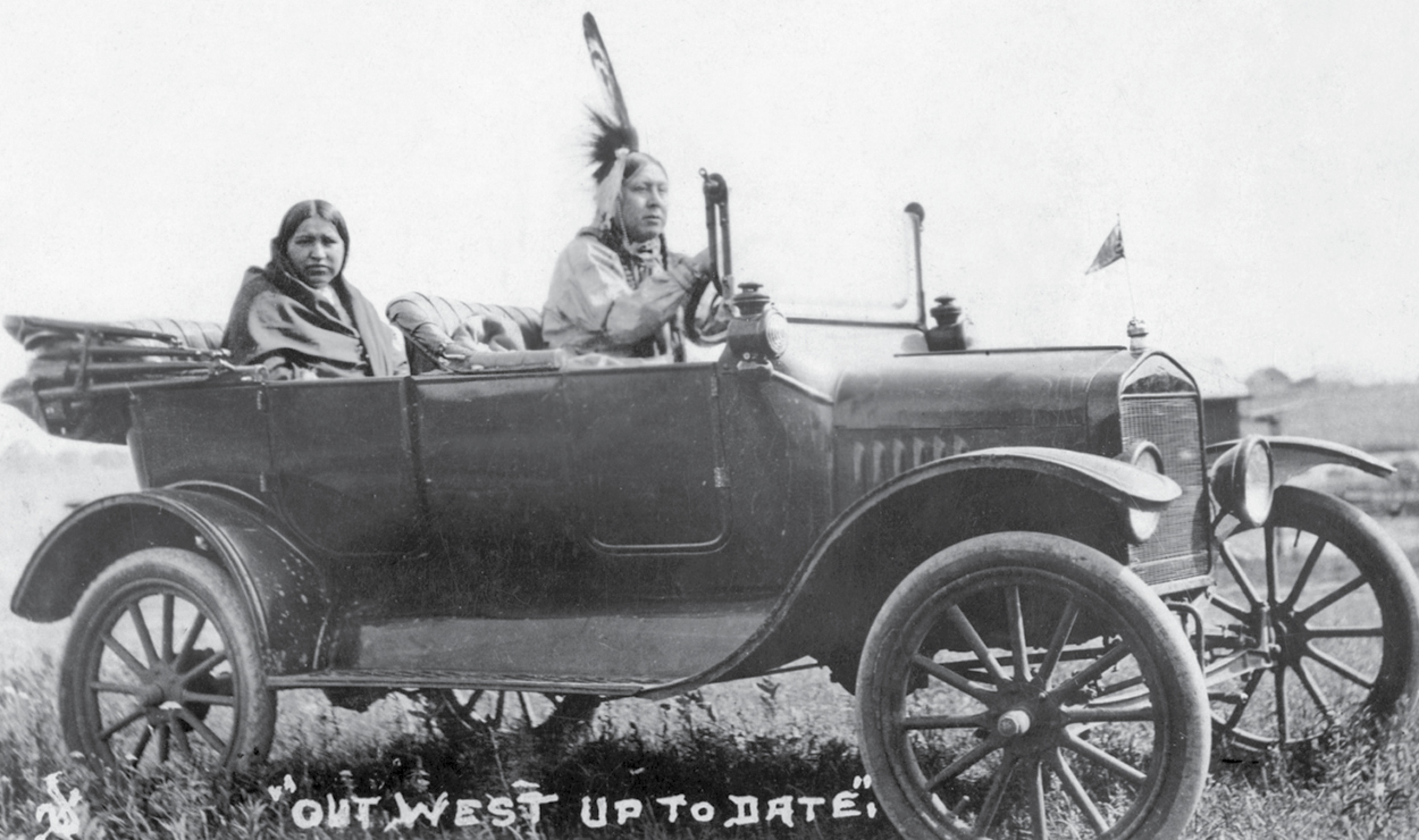

![]() The press claimed that whereas one out of every eleven Americans owned a car, virtually every Osage had eleven of them. Credit 26

The press claimed that whereas one out of every eleven Americans owned a car, virtually every Osage had eleven of them. Credit 26

Many Osage, unlike other wealthy Americans, could not spend their money as they pleased because of the federally imposed system of financial guardians. (One guardian claimed that an Osage adult was “like a child six or eight years old, and when he sees a new toy he wants to buy it.”) The law mandated that guardians be assigned to any American Indians whom the Department of the Interior deemed “incompetent.” In practice, the decision to appoint a guardian—to render an American Indian, in effect, a half citizen—was nearly always based on the quantum of Indian blood in the property holder, or what a state supreme court justice referred to as “racial weakness.” A full-blooded American Indian was invariably appointed a guardian, whereas a mixed-blood person rarely was. John Palmer, the part-Sioux orphan who had been adopted by an Osage family and who played such an instrumental role in preserving the tribe’s mineral rights, pleaded to members of Congress, “Let not that quantum of white blood or Indian determine the amount that you take over from the members of this tribe. It matters not about the quantum of Indian blood. You gentlemen do not deal with things of that kind.”

Such pleas, inevitably, were ignored, and members of Congress would gather in wood-paneled committee rooms and spend hours examining in minute detail the Osage’s expenditures, as if the country’s security were at stake. At a House subcommittee hearing in 1920, lawmakers combed through a report from a government inspector who had been sent to investigate the tribe’s spending habits, including those of Mollie’s family. The investigator cited with displeasure “Exhibit Q”: a bill for $319.05 that Mollie’s mother, Lizzie, had racked up at a butcher shop before her death.

The investigator insisted that the devil had been in control of the government when it negotiated the oil-rights agreement with the tribe. Full of fire and brimstone, he declared, “I have visited and worked in and about most of the cities of our country, and am more or less familiar with their filthy sores and iniquitous cesspools. Yet I never wholly appreciated the story of Sodom and Gomorrah, whose sins and vices proved their undoing and their downfall, until I visited this Indian nation.”

He implored Congress to take greater action. “Every white man in Osage County will tell you that the Indians are now running wild,” he said, adding, “The day has come when we must begin our restriction of these moneys or dismiss from our hearts and conscience any hope we have of building the Osage Indian into a true citizen.”

A few congressmen and witnesses tried to mitigate the scapegoating of the Osage. At a subsequent hearing, even a judge who served as a guardian acknowledged that rich Indians spent their wealth no differently than white people with money did. “There is a great deal of humanity about these Osages,” he said. Hale also argued that the government should not be dictating the Osage’s financial decisions.

But in 1921, just as the government had once adopted a ration system to pay the Osage for seized land—just as it always seemed to turn its gospel of enlightenment into a hammer of coercion—Congress implemented even more draconian legislation controlling how the Osage could spend their money. Guardians would not only continue to oversee their wards’ finances; under the new law, these Osage Indians with guardians were also “restricted,” which meant that each of them could withdraw no more than a few thousand dollars annually from his or her trust fund. It didn’t matter if these Osage needed their money to pay for education or a sick child’s hospital bills. “We have many little children,” the last hereditary chief of the tribe, who was in his eighties, explained in a statement issued to the press. “We want to raise them and educate them. We want them to be comfortable, and we do not want our money held up from us by somebody who cares nothing for us.” He went on, “We want our money now. We have it. It is ours, and we don’t want some autocratic man to hold it up so we can’t use it….It is an injustice to us all. We do not want to be treated like a lot of little children. We are men and able to take care of ourselves.” As a full-blooded Osage, Mollie was among those whose funds were restricted, though at least her husband, Ernest, was her guardian.

It wasn’t only the federal government that was meddling in the tribe’s financial affairs. The Osage found themselves surrounded by predators—“a flock of buzzards,” as one member of the tribe complained at a council meeting. Venal local officials sought to devour the Osage’s fortunes. Stickup men were out to rob their bank accounts. Merchants demanded that the Osage pay “special”—that is, inflated—prices. Unscrupulous accountants and lawyers tried to exploit full-blooded Osage’s ill-defined legal status. There was even a thirty-year-old white woman in Oregon who sent a letter to the tribe, seeking a wealthy Osage to marry: “Will you please tell the richest Indian you know of, and he will find me as good and true as any human being can be.”

At one congressional hearing, another Osage chief named Bacon Rind testified that the whites had “bunched us down here in the backwoods, the roughest part of the United States, thinking ‘we will drive these Indians down to where there is a big pile of rocks and put them there in that corner.’ ” Now that the pile of rocks had turned out to be worth millions of dollars, he said, “everybody wants to get in here and get some of this money.”