7

THIS THING OF DARKNESS

THIS THING OF DARKNESS

In the first days of February 1923, the weather turned violently cold. Icy winds cut across the plains and howled through the ravines and rattled tree branches. The prairie became as hard as stone, birds disappeared from the sky, and the Grandfather sun looked pale and distant.

One day, two men were out hunting four miles northwest of Fairfax when they spotted a car at the bottom of a rocky swale. Rather than approaching it, the hunters returned to Fairfax and informed authorities, and a deputy sheriff and the town marshal went to investigate. In the dying light, they walked down a steep slope toward the vehicle. Curtains, as vehicles often had back then, obscured the windows, and the car, a Buick, resembled a black coffin. On the driver’s side, there was a small opening in the curtain, and the deputy peered through it. A man was slumped behind the steering wheel. “He must be drunk,” the deputy said. But as he yanked open the driver’s door, he saw blood, on the seat and on the floor. The man had been fatally shot in the back of the head. The angle of the shot, along with the fact that there was no gun present, ruled out suicide. “I seen he had been murdered,” the deputy later recalled.

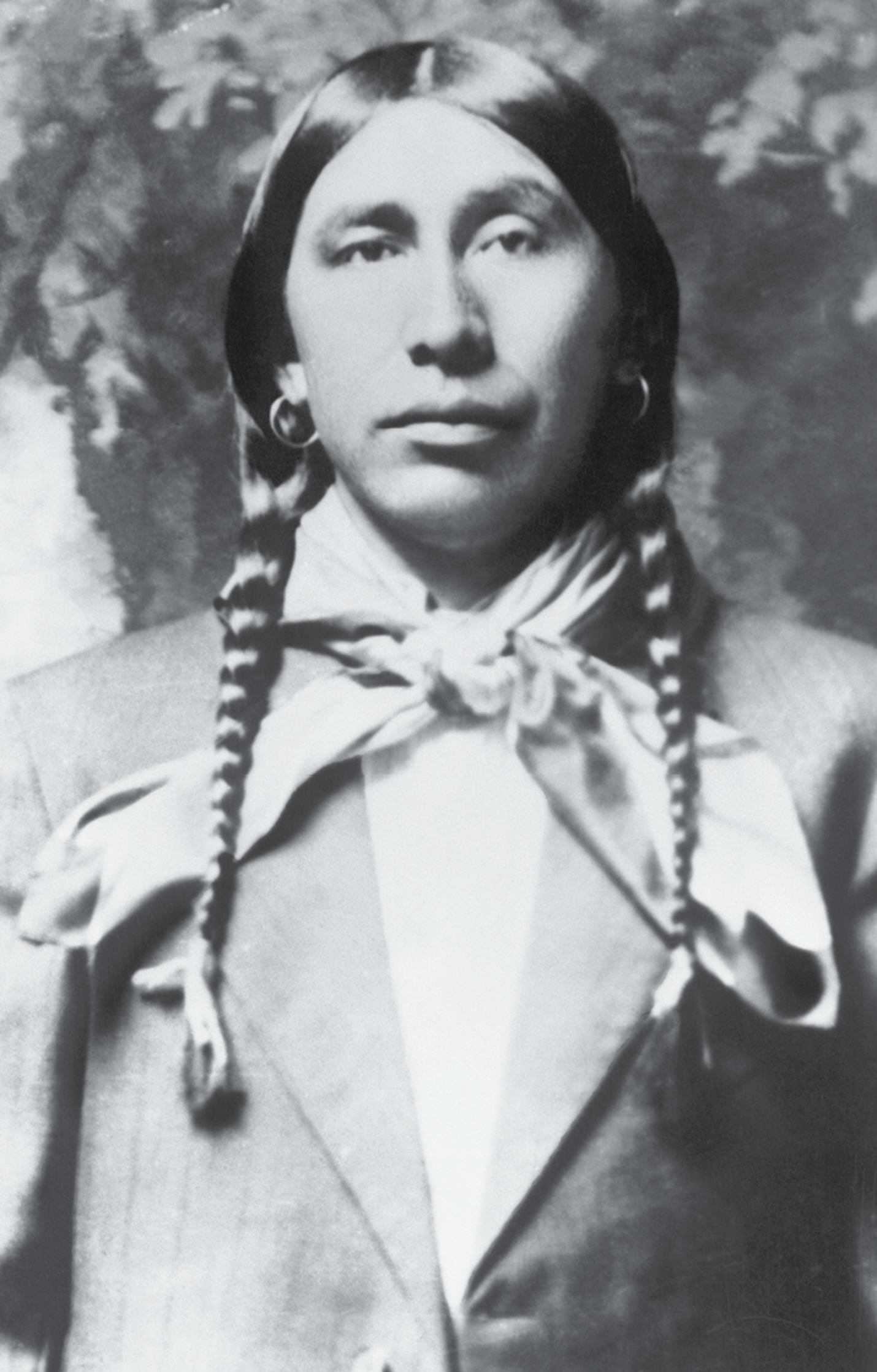

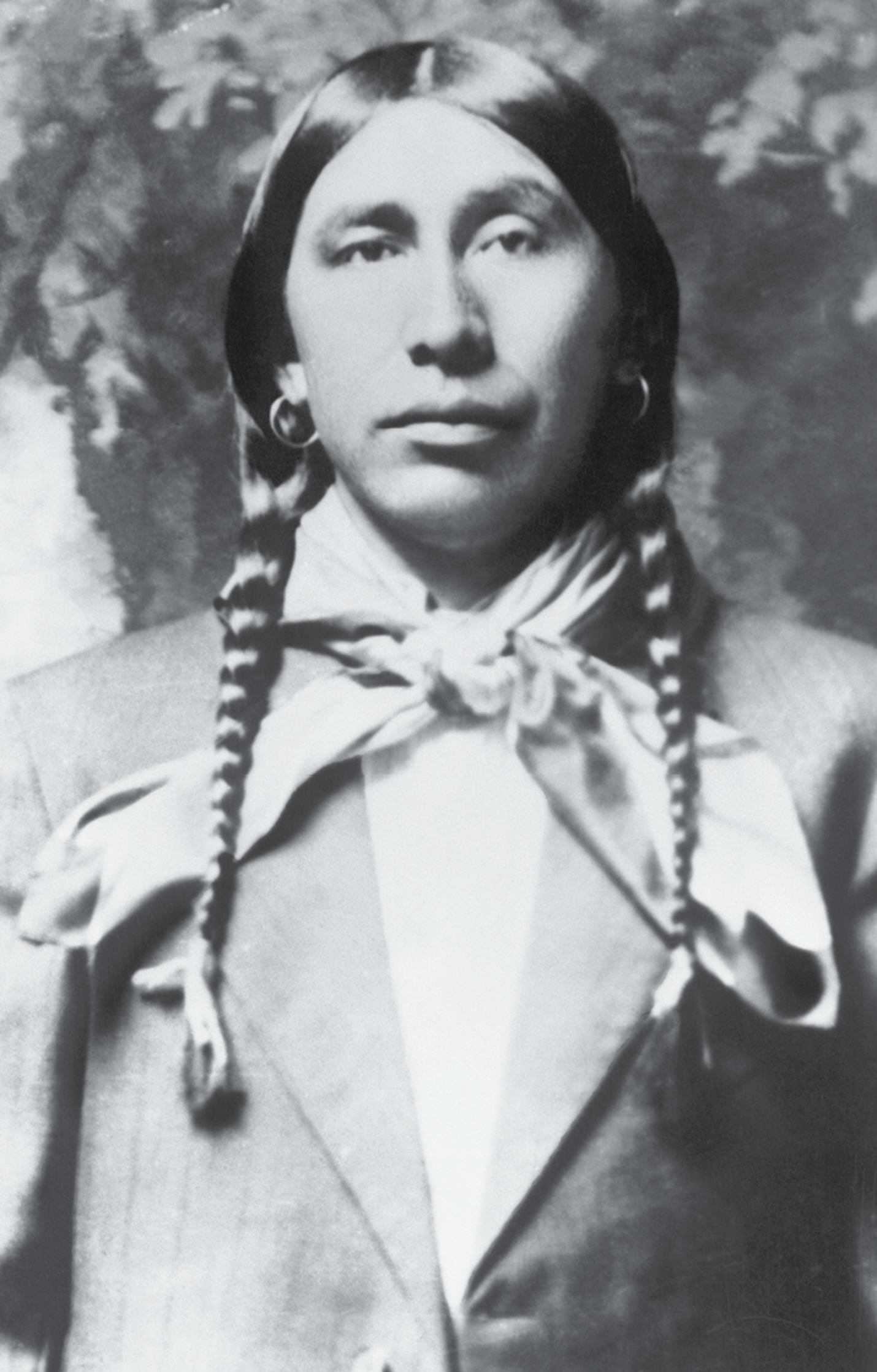

Since the brutal slaying of the oilman McBride, nearly six months had passed without the discovery of another suspicious death. Yet as the two lawmen stared at the man in the car, they realized that the killing hadn’t stopped after all. The corpse was mummified by the cold, and this time the lawmen had no trouble identifying the victim: Henry Roan, a forty-year-old Osage Indian who was married with two children. He’d once worn his hair in two long braids before being forced to cut them off at boarding school, just as he’d been made to change his name from Roan Horse. Even without the braids—even entombed in the car—his long, handsome face and tall, lean body evoked those of an Osage warrior.

The lawmen returned to Fairfax, where they notified the justice of the peace. They also made sure that Hale was informed; as the mayor of Fairfax recalled, “Roan considered W. K. Hale his best friend.” Roan was one of the full-bloods whose financial allowance had been officially curtailed, and he had often asked Hale to advance him cash. “We were good friends and he sought my aid when in trouble,” Hale later recalled, adding that he’d given his friend so many loans that Roan had listed him as the beneficiary on his $25,000 life-insurance policy.

![]() Henry Roan Credit 27

Henry Roan Credit 27

A couple of weeks before his death, Roan had phoned Hale, distraught. Roan had learned that his wife was having an affair with a man named Roy Bunch. Hale went to visit with Roan and tried to console him.

Several days later, Hale bumped into Roan at the bank in downtown Fairfax. Roan asked him if he could borrow a few dollars; he was still morose about his wife, and he wanted to get a drink of moon liquor. Hale advised him not to buy any whiskey: “Henry, you better quit that. It’s hurting you.” And he warned him that the Prohibition men were “going to get” him.

“I am not going to bring any to town,” Roan said. “I will hide it out.”

Roan then disappeared, until his body turned up.

Once more, the macabre rituals began. The deputy and the marshal returned to the ravine, and Hale went with them. By then, darkness had enshrouded the crime scene, and the men lined up their vehicles on the hill and shone their headlights down into the depths below—into what one law-enforcement official called “truly a valley of death.”

Hale remained on top of the hill and watched as the coroner’s inquest began, the men bobbing in and out of the silhouetted Buick. One of the Shoun brother doctors concluded that the time of death was around ten days earlier. The lawmen noted the position of Roan’s body—“his hands folded across his breast and his head on the seat”—and how the bullet had exited through his right eye and then shattered the windshield. They noted the broken glass strewn on the hood and on the ground beyond. They noted the things he carried: “$20 in greenback, two silver dollars, and…a gold watch.” And the lawmen noted nearby tread marks in the frozen mud from another car—presumably the assassin’s.

Word of the murder rekindled the sense of prickly dread. The Osage Chief—which, in the same issue, happened to carry a tribute to Abraham Lincoln as an inspiration to Americans—stated on its front page, HENRY ROAN SHOT BY UNKNOWN HAND.

The news jolted Mollie. In 1902, more than a decade before meeting Ernest, she and Roan had been briefly married. There are few surviving accounts detailing the relationship, but it was likely an arranged marriage: youths—Mollie was only fifteen at the time—pressed together to preserve a vanishing way of life. Because the marriage had been contracted according to Osage custom, there was no need for a legal divorce, and they simply went their own ways. Still, they remained bound by a memory of a fleeting intimacy that had apparently ended with no bitterness and perhaps even some hidden warmth.

Many people in the county turned out for Roan’s funeral. The Osage elders sang the traditional songs for the dead, only now the songs seemed for the living, for those who had to endure this world of killing. Hale served again as a pallbearer, holding aloft the casket of his friend. One of Hale’s favorite poems echoed Jesus’s command in the Sermon on the Mount:

Man’s judgment errs, but there is One who “doeth all things well.”

Ever, throughout the voyage of life, this precept keep in view:

“Do unto others as thou wouldst that they should do to you.”

Mollie had always assisted the authorities, but as they began looking into Roan’s death, she became uneasy. She was, in her own way, a product of the spirit of American self-construction. She arranged the details of her past the way she tidied up her house, and she had never told Ernest, her instinctively jealous second husband, about her Osage wedding with Roan. Ernest had provided Mollie support during these terrible times, and they had recently had a third child, a girl whom they had named Anna. If Mollie were to let the authorities know of her connection to Roan, she would have to admit to Ernest that she’d deceived him all these years. And so she decided not to say a word, not to her husband or the authorities. Mollie had her secrets, too.

After Roan’s death, electric lightbulbs began to appear on the outside of Osage houses, dangling from rooftops and windowsills and over back doors, their collective glow hollowing the dark. An Oklahoma reporter observed, “Travel in any direction that you will from Pawhuska and you will notice at night Osage Indian homes outlined with electric lights, which a stranger in the country might conclude to be an ostentatious display of oil wealth. But the lights are burned, as every Osage knows, as protection against the stealthy approach of a grim specter—an unseen hand—that has laid a blight upon the Osage land and converted the broad acres, which other Indian tribes enviously regard as a demi-paradise, into a Golgotha and field of dead men’s skulls….The perennial question in the Osage land is, ‘who will be next?’ ”

The murders had created a climate of terror that ate at the community. People suspected neighbors, suspected friends. Charles Whitehorn’s widow said she was sure that the same parties who had murdered her husband would soon “do away with her.” A visitor staying in Fairfax later recalled that people were overcome by “paralyzing fear,” and a reporter observed that a “dark cloak of mystery and dread…covered the oil-bespattered valleys of the Osage hills.”

In spite of the growing risks, Mollie and her family pressed on with their search for the killers. Bill Smith confided in several people that he was getting “warm” with his detective work. One night, he was with Rita at their house, in an isolated area outside Fairfax, when they thought that they heard something moving around the perimeter of the house. Then the noise stopped; whatever, whoever, it was had disappeared. A few nights later, Bill and Rita heard the jostling again. Intruders—yes, they had to be—were outside, rattling objects, probing, then vanishing. Bill told a friend, “Rita’s scared,” and Bill seemed to have lost his bruising confidence.

Less than a month after Roan’s death, Bill and Rita fled their home, leaving behind most of their belongings. They moved into an elegant, two-story house, with a porch and a garage, near the center of Fairfax. (They’d bought the house from the doctor James Shoun, who was a close friend of Bill’s.) Several of the neighbors had watchdogs, which barked at the slightest disturbance; surely, these animals would signal if the intruders returned. “Now that we’ve moved,” Bill told a friend, “maybe they’ll leave us alone.”

Not long afterward, a man appeared at the Smiths’ door. He told Bill that he’d heard he was selling some farmland. Bill told him that he was mistaken. The man, Bill noticed, had a wild look about him, the look of an outlaw, and he kept glancing around the house as if he were casing it.

In early March, the dogs in the neighborhood began to die, one after the other; their bodies were found slumped on doorsteps and on the streets. Bill was certain that they’d been poisoned. He and Rita found themselves in the grip of tense silence. He confided in a friend that he didn’t “expect to live very long.”

On March 9, a day of swirling winds, Bill drove with a friend to the bootlegger Henry Grammer’s ranch, which was on the western edge of the reservation. Bill told his friend that he needed a drink. But Bill knew that Grammer, whom the Osage Chief called the “county’s most notorious character,” possessed secrets and controlled an unseen world. The Roan investigation had produced one revelation: before disappearing, Roan had said that he was going to get whiskey at Grammer’s ranch—the same place, coincidentally or not, where Mollie’s sister Anna often got her whiskey, too.

Grammer was a rodeo star who had performed at Madison Square Garden and been crowned the steer-roping champion of the world. He was also an alleged train robber, a kingpin bootlegger with connections to the Kansas City Mob, and a blazing gunman. The porous legal system seemed unable to contain him. In 1904, in Montana, he gunned down a sheepshearer, yet he received only a three-year sentence. In a later incident, in Osage County, a man came into a hospital bleeding profusely from a gunshot wound, moaning, “I’m going to die, I’m going to die.” He fingered Grammer as his shooter, then passed out. But when the victim woke up the next day and realized that he wasn’t going to the heavenly Lord—at least not anytime soon—he insisted that he had no idea who had pulled the trigger. As Grammer’s bootlegging empire grew, he held sway over an army of bandits. They included Asa Kirby, a stickup man who had glimmering gold front teeth, and John Ramsey, a cow rustler who seemed the least bad of Grammer’s bad men.

![]() Henry Grammer received a three-year sentence after he killed a man in Montana. Credit 28

Henry Grammer received a three-year sentence after he killed a man in Montana. Credit 28

Bill and his friend arrived at Grammer’s ranch in the gathering dusk. A large wooden house and a barn loomed before them, and hidden in the surrounding woods were five-hundred-gallon copper stills. Grammer had set up his own private power plant so that his gangs could work all day and all night—the furtive light of the moon no longer needed to manufacture moonshine.

Finding that Grammer was away, Bill asked one of the workers for several jars of whiskey. He took a swig. In a nearby pasture, Grammer’s prized horses often roamed. How easy it would have been for Bill, the old horse thief, to mount one and disappear. Bill drank some more. Then he and his friend drove back to Fairfax, passing the strings of lightbulbs—the ’fraid lights, as they were called—that shivered in the wind.

Bill dropped his friend off, and when he got home, he pulled his Studebaker in to the garage. Rita was in the house with Nettie Brookshire, a nineteen-year-old white servant who often stayed over.

![]() Rita Smith and her servant Nettie Brookshire at a summer retreat Credit 29

Rita Smith and her servant Nettie Brookshire at a summer retreat Credit 29

They soon went to bed. Just before three in the morning, a man who lived nearby heard a loud explosion. The force of the blast radiated through the neighborhood, bending trees and signposts and blowing out windows. In a Fairfax hotel, a night watchman sitting by a window was showered with broken glass and thrown to the floor. In another room of the hotel, a guest was hurled backward. Closer to the blast, doors on houses were smashed and torn asunder; wooden beams cracked like bones. A witness who had been a boy at the time later wrote, “It seemed that the night would never stop trembling.” Mollie and Ernest felt the explosion, too. “It shook everything,” Ernest later recalled. “At first I thought it was thunder.” Mollie, frightened, got up and went to the window and could see something burning in the distant sky, as if the sun had burst violently into the night. Ernest went to the window and stood there with her, the two of them looking out at the eerie glow.

Ernest slipped on his trousers and ran outside. People were stumbling from their houses, groggy and terrified, carrying lanterns and firing guns in the air, a warning signal and a call for others to join what was a growing procession—a rush of people moving, on foot and in cars, toward the site of the blast. As people got closer, they cried out, “It’s Bill Smith’s house! It’s Bill Smith’s house!” Only there was no longer a house. Nothing but heaps of charred sticks and twisted metal and shredded furniture, which Bill and Rita had purchased just days earlier from the Big Hill Trading Company, and strips of bedding hanging from telephone wires and pulverized debris floating through the black toxic air. Even the Studebaker had been demolished. A witness struggled for words: “It just looked like, I don’t know what.” Clearly, someone had planted a bomb under the house and detonated it.

The flames amid the rubble consumed the remaining fragments of the house and gusted into the sky, a nimbus of fire. Volunteer firemen were carrying water from wells and trying to put out the blaze. And people were looking for Bill and Rita and Nettie. “Come on men, there’s a woman in there,” one rescuer cried out.

The justice of the peace had joined the search, and so had Mathis and the Shoun brothers. Even before remains were found, the Big Hill Trading Company undertaker had arrived with his hearse; a rival undertaker showed up as well, the two hovering like predatory birds.

The searchers scoured the ruins. James Shoun, having once owned the house, knew where the main bedroom had been situated. He combed in the vicinity, and that’s when he heard a voice calling out. Others could hear it, too, faint but distinct: “Help!…Help!” A searcher pointed to a smoldering mound above the voice. Firemen doused the area with water, and amid the steaming smoke everyone began clawing the rubble away. As they worked, the voice grew louder, rising over the sound of the heaving, creaking wreckage. Finally, a face began to take shape, blackened and tormented. It was Bill Smith. He was writhing by his bed. His legs were seared beyond recognition. So were his back and hands. David Shoun later recalled that in all his years as a doctor he’d never seen a man in such agony: “He was halloing and was in awful misery.” James Shoun tried to comfort Bill, telling him, “I won’t let you suffer.”

As the group of men cleared the debris, they could see that Rita was lying beside him in her nightgown. Her face was unmarred, and she looked as if she were still peacefully sleeping, in a dream. But when they lifted her up, they saw that the back of her head was crushed. She had no more life in her. When Bill realized that she was dead, he let out a torturous cry. “Rita’s gone,” he repeated. He told a friend who was there, “If you’ve got a pistol…”

Ernest, wearing a bathrobe that someone had handed him to cover himself, was looking on. He was unable to turn away from the horror, and he kept muttering, “Some fire.” The Big Hill undertaker asked him for permission to remove Rita’s remains, and Ernest consented. Someone had to embalm her before Mollie saw her. What would she say when she learned that another sister had been murdered? Now Mollie, once expected to die first because of her diabetes, was the only one left.

The searchers couldn’t find Nettie. The justice of the peace determined that the young woman, who was married and had a child, had been “blown to pieces.” There weren’t even sufficient remains for an inquest, though the rival undertaker found enough to claim the fee for a burial. “I figured on getting back and getting the hired girl with the hearse, but he beat me,” the Big Hill undertaker said.

The doctors and the others lifted Bill Smith up as he grabbed for breath. They carried him toward an ambulance and took him to the Fairfax Hospital, where David Shoun injected him multiple times with morphine. He was the lone survivor, but before he could be questioned, he lost consciousness.

It had taken a while for local lawmen to arrive at the hospital. The town marshal and other officers had been in Oklahoma City for a court case. “The time of the deed was also deliberate,” an investigator later noted, because it was done when officers “were all away.” After hearing the news and rushing back to Fairfax, lawmen set up floodlights at the front and rear exits of the hospital, in case the killers planned to finish off Bill there. Armed guards kept watch, too.

![]() Rita and Bill Smith’s house before the blast—and then after Credit 30

Rita and Bill Smith’s house before the blast—and then after Credit 30

In a state of delirium, wavering between life and death, Bill would sometimes mutter, “They got Rita and now it looks like they’ve got me.” The friend who had accompanied him to Grammer’s ranch came to see him. “He just kind a jabbered,” the friend recalled. “I couldn’t understand anything he said.”

After nearly two days, Bill regained consciousness. He asked about Rita. He wanted to know where she was buried. David Shoun said he thought that Bill, fearing he might die, was about to make a declaration—to reveal what he knew about the bombing and the killers. “I tried to get it out of him,” the doctor later told authorities. “I said, ‘Bill, have you any idea who did it?’ I was anxious to know.” But the doctor said Bill never did disclose anything relevant. On March 14, four days after the bombing, Bill Smith died—another victim of what had become known as the Osage Reign of Terror.

A Fairfax newspaper published an editorial arguing that the bombing was beyond comprehension—“beyond our power to realize that humans would stoop so low.” The paper demanded that the law “leave no stone unturned to ferret out the perpetrators and bring them to justice.” A firefighter at the scene had told Ernest that those responsible for this “should be thrown in the fire and burned.”

In April 1923, Governor Jack C. Walton of Oklahoma dispatched his top state investigator, Herman Fox Davis, to Osage County. A lawyer and a former private detective with the Burns agency, Davis had a groomed sleekness. He puffed on cigars, his eyes shining through a veil of blue smoke. A law-enforcement official called him the epitome of a “dime-novel detective.”

Many Osage had come to believe that local authorities were colluding with the killers and that only an outside force like Davis could cut through the corruption and solve the growing number of cases. Yet within days Davis was spotted consorting with some of the county’s notorious criminals. Another investigator then caught Davis taking a bribe from the head of a local gambling syndicate in exchange for letting him operate his illicit businesses. And it soon became clear that the state’s special investigator in charge of solving the Osage murder cases was himself a crook.

In June 1923, Davis pleaded guilty to bribery and received a two-year sentence, but a few months later he was pardoned by the governor. Then Davis and several conspirators proceeded to rob—and murder—a prominent attorney; this time, Davis received a life sentence. In November, Governor Walton was impeached and removed from office, partly for having abused the system of pardons and paroles (and having turned “loose upon the honest citizens of the state a horde of murderers and criminals”) and partly for having received illicit contributions from the oilman E. W. Marland that were used to build a lavish home.

Amid this garish corruption, W. W. Vaughan, a fifty-four-year-old attorney who lived in Pawhuska, tried to act with decency. A former prosecutor who vowed to eliminate the criminal element that was a “parasite upon those who make their living by honest means,” he had worked closely with the private investigators struggling to solve the Osage murder cases. One day in June 1923, Vaughan received an urgent call. It was from a friend of George Bigheart, who was a nephew of the legendary chief James Bigheart. Suffering from suspected poisoning, Bigheart—who was forty-six and who had once written on a school application that he hoped to “help the needy, feed the hungry and clothe the naked”—had been rushed to a hospital in Oklahoma City. His friend said that he had information about the murders of the Osage but would speak only to Vaughan, whom he trusted. When Vaughan asked about Bigheart’s condition, he was told to hurry.

Before leaving, Vaughan informed his wife, who had recently given birth to their tenth child, about a hiding spot where he had stashed evidence that he had been gathering on the murders. If anything should happen to him, he said, she should take it out immediately and turn it over to the authorities. She would also find money there for her and the children.

When Vaughan got to the hospital, Bigheart was still conscious. There were others in the room, and Bigheart motioned for them to leave. Bigheart then apparently shared his information, including incriminating documents. Vaughan remained at Bigheart’s side for several hours, until he was pronounced dead. Then Vaughan telephoned the new Osage County sheriff to say that he had all the information he needed and that he was rushing back on the first train. The sheriff pressed him if he knew who had killed Bigheart. Oh, he knew more than that, Vaughan said.

He hung up and went to the station where he was seen boarding an overnight train. When the train pulled in to the station the next day, though, there was no sign of him. OWNER VANISHES LEAVING CLOTHES IN PULLMAN CAR, the Tulsa Daily World reported. MYSTERY CLOAKS DISAPPEARANCE OF W. W. VAUGHAN OF PAWHUSKA.

The Boy Scouts, whose first troop in the United States was organized in Pawhuska, in 1909, joined the search for Vaughan. Bloodhounds hunted for his scent. Thirty-six hours later, Vaughan’s body was spotted lying by the railroad tracks, thirty miles north of Oklahoma City. He’d been thrown from the train; his neck was broken, and he’d been stripped virtually naked, just like the oilman McBride. The documents Bigheart had given him were gone, and when Vaughan’s widow went to the designated hiding spot, it had been cleaned out.

The justice of the peace was asked by a prosecutor if he thought that Vaughan had known too much. The justice replied, “Yes, sir, and had valuable papers on his person.”

The official death toll of the Osage Reign of Terror had climbed to at least twenty-four members of the tribe. Among the victims were two more men who had tried to assist the investigation: one, a prominent Osage rancher, plunged down a flight of stairs after being drugged; the other was gunned down in Oklahoma City on his way to brief state officials about the case. News of the murders began to spread. In an article titled “The ‘Black Curse’ of the Osages,” the Literary Digest, a national publication, reported that members of the tribe had been “shot in lonely pastures, bored by steel as they sat in their automobiles, poisoned to die slowly, and dynamited as they slept in their homes.” The article went on, “In the meantime the curse goes on. Where it will end, no one knows.” The world’s richest people per capita were becoming the world’s most murdered. The press later described the killings as being as “dark and sordid as any murder story of the century” and the “bloodiest chapter in American crime history.”

![]() W. W. Vaughan with his wife and several of their children Credit 32

W. W. Vaughan with his wife and several of their children Credit 32

All efforts to solve the mystery had faltered. Because of anonymous threats, the justice of the peace was forced to stop convening inquests into the latest murders. He was so terrified that merely to discuss the cases, he would retreat into a back room and bolt the door. The new county sheriff dropped even a pretense of investigating the crimes. “I didn’t want to get mixed up in it,” he later admitted, adding cryptically, “There is an undercurrent like a spring at the head of the hollow. Now there is no spring, it is gone dry, but it is broke way down to the bottom.” Of solving the cases, he said, “It is a big doings and the sheriff and a few men couldn’t do it. It takes the government to do it.”

In 1923, after the Smith bombing, the Osage tribe began to urge the federal government to send investigators who, unlike the sheriff or Davis, had no ties to the county or to state officials. The Tribal Council adopted a formal resolution that stated:

WHEREAS, in no case have the criminals been apprehended and brought to justice, and,

WHEREAS, the Osage Tribal Council deems it essential for the preservation of the lives and property of members of the tribe that prompt and strenuous action be taken to capture and punish the criminals…

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED, that the Honorable Secretary of the Interior be requested to obtain the services of the Department of Justice in capturing and prosecuting the murderers of the members of the Osage Tribe.

Later, John Palmer, the half-Sioux lawyer, sent a letter to Charles Curtis, a U.S. senator from Kansas; part-Kaw, part-Osage, Curtis was then the highest official with acknowledged Indian ancestry ever elected to office. Palmer told Curtis that the situation was more dire than anyone could possibly imagine and that unless he and other men of influence got the Department of Justice to act, the “Demons” behind the “most foul series of crimes ever committed in this country” would escape justice.

While the tribe waited for the federal government to respond, Mollie lived in dread, knowing that she was the likely next target in the apparent plot to eliminate her family. She couldn’t forget the night, several months before the explosion, when she had been in bed with Ernest and heard a noise outside her house. Someone was breaking into their car. Ernest comforted Mollie, whispering, “Lie still,” as the perpetrator roared away in the stolen vehicle.

When the bombing occurred, Hale had been in Texas, and he now saw the charred detritus of the house, which resembled a wreckage of war—“a horrible monument,” as one investigator called it. Hale promised Mollie that somehow he’d avenge her family’s blood. When Hale heard that a band of outlaws—perhaps the same band responsible for the Reign of Terror—was planning to rob a store owner who kept diamonds in a safe, he handled the matter himself. He alerted the shopkeeper, who lay in wait; sure enough, that night the shopkeeper saw the intruders breaking in and blew one of them away with his single-barreled, 12-gauge shotgun. After the other outlaws fled, authorities went to inspect the dead man and saw his gold front teeth. It was Asa Kirby, Henry Grammer’s associate.

![]() Mollie with her sisters Rita (left), Anna (second from left), and Minnie (far right) Credit 33

Mollie with her sisters Rita (left), Anna (second from left), and Minnie (far right) Credit 33

One day, Hale’s pastures were set on fire, the blaze spreading for miles, the blackened earth strewn with the carcasses of cattle. To Mollie, even the King of the Osage Hills seemed vulnerable, and after pursuing justice for so long, she retreated behind the closed doors and the shuttered windows of her house. She stopped entertaining guests or attending church; it was as if the murders had shattered even her faith in God. Among residents of the county, there were whispers that she’d locked herself away lest she go mad or that her mind was already unraveling under the strain. Her diabetes also appeared to be worsening. The Office of Indian Affairs received a note from someone who knew Mollie, saying that she was “in failing health and is not expected to live very long.” Consumed by fear and ill health, she gave her third child, Anna, to a relative to be raised.

Time ground on. There are few records, at least authoritative ones, of Mollie’s existence during this period. No record of how she felt when agents from the Bureau of Investigation—an obscure branch of the Justice Department that in 1935, would be renamed the Federal Bureau of Investigation—finally arrived in town. No record of what she thought of physicians like the Shoun brothers, who were constantly coming and going, injecting her with what was said to be a new miracle drug: insulin. It was as if, after being forced to play a tragic hand, she’d dealt herself out of history.

Then, in late 1925, the local priest received a secret message from Mollie. Her life, she said, was in danger. An agent from the Office of Indian Affairs soon picked up another report: Mollie wasn’t dying of diabetes at all; she, too, was being poisoned.