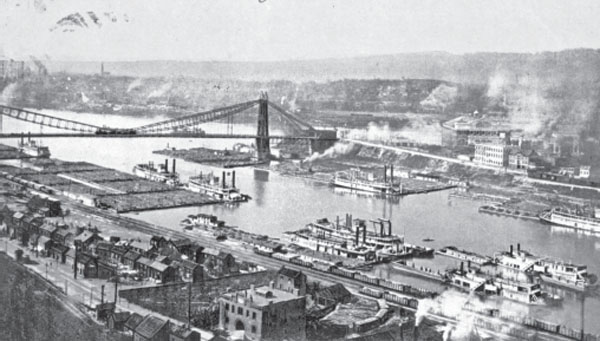

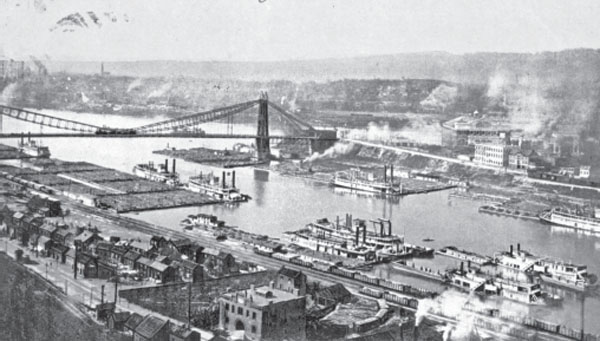

Point Bridge, over the Monongahela River. New York Public Library Digital Collection.

INTRODUCTION

A writer named James Parton once called Pittsburgh “hell with the lid off.” We’ll let you decide how accurate that is, but we can say this without fear of contradiction: Pittsburgh’s character was forged in pig iron furnaces so hot that men and women sometimes forgot their fear of hell. Any town that has lived through the turbulence Pittsburgh has experienced cannot escape its ghosts, and Pittsburgh is teeming with them. Pittsburgh has a North Side and a South Side—this book explores its dark side.

In the middle of the eighteenth century, the land that would become Pittsburgh was among the most hotly contested places on earth. On July 9, 1755, a British expedition led by Major General Edward Braddock marched toward the Point, where the Allegheny, Monongahela and Ohio Rivers meet, to kick the French out once and for all, but the French and their Native American allies intercepted and routed the British. That night, the French and the Native Americans marched British soldiers captured in the battle to Fort Duquesne at the Point. There, on the banks of the Allegheny facing present-day Heinz Field, the Native Americans tied a dozen British soldiers to stakes and burned them alive.

In that cauldron of blood and wickedness was Pittsburgh born, and the taint of evil lingers still.

Many of this book’s tales are from one especially turbulent era—the time when Pittsburgh was bursting onto the world stage as the industrial capital of America. That era happens to coincide with the time that Pittsburgh was officially spelled without the h. In 1890, the U.S. Board of Geographic Names ordained that the h be dropped, and it was not until twenty-one years later that the protests of Pittsburghers were heeded and the h was reinstated.

Point Bridge, over the Monongahela River. New York Public Library Digital Collection.

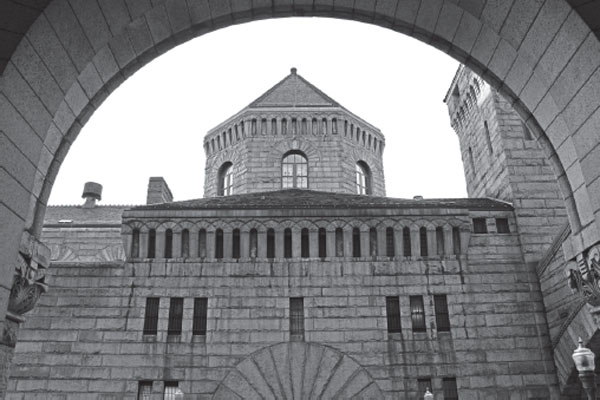

The old Allegheny County jail. Tim Murray.

The rivers are Pittsburgh’s lifeblood, and steel is imprinted on its DNA. At one time, Pittsburgh made half the steel in America. By the early twentieth century, Pittsburgh was bursting with millionaires, but for most people, this town was a downright dangerous place. In 1905—in just that one year—17,700 men were killed or maimed in Allegheny County while performing industrial jobs, mostly working in iron and steel mills. That is a staggering percentage of the total population.

But sometimes it wasn’t safe to stay home, either. On January 28, 1907, Pittsburgher Albert Houck came home from work to find that his wife had spontaneously combusted. Her body was reduced to charred cinders and ashes, and nothing else in the room was burned. Mr. Houck found her sprawled out on a table, and not even the table was singed.

But wait—the stories get even stranger, even creepier. Come, journey with us back to the Gilded Age of ragtime and robber barons, of boastful mansions bathed in gaslight and of a time when the New York Times said of Pittsburgh, “men of great wealth . . . [sprang] up from obscurity like mushrooms, and the tales of their sudden acquisitions of fortunes read like chapters from the Arabian Nights.”

One of Pittsburgh’s many bridges leading into Downtown Pittsburgh across the Allegheny River. Tim Murray.

Three of Pittsburgh’s many bridges on the Allegheny River. Tim Murray.

Downtown Pittsburgh, including the Gulf Building. Tim Murray.

A word about our goal in writing this book. With each passing year, many of the classic Pittsburgh ghost stories have faded from the public’s consciousness. It is our mission at Haunted Pittsburgh to chronicle and preserve these stories. We are the curators of Pittsburgh’s nightmares, the archivists of its fears, the trustees of all things that go “bump in the night” in western Pennsylvania. The stories are fascinating, and they also tell us much about Pittsburgh’s majestic, sometimes grisly history, a history that isn’t well known today. Sadly, there are all too many people who don’t know there used to be a mighty steel mill in Homestead that dwarfed almost any other in the world; who have never heard of Jonas Salk, much less that he played a critical role in wiping out polio from a laboratory in Pittsburgh; who think Roberto Clemente is a bridge, Arnold Palmer is a drink and Warhol is a museum.

This is Pittsburgh’s story—told through the dark and twisted lens of its greatest tales of ghosts and the unexplained.