Happier days … Aubrey in jail, intact.

I WAS a revolutionary who lost his ideals in heroin, a philosopher who lost his integrity in crime, and a poet who lost his soul in a maximum security prison. When I escaped over the front wall, between two gun towers, I became my country’s most wanted man. Luck ran with me and flew me across the world to India, where I joined the Bombay mafia. I worked as a gunrunner, a smuggler, and a counterfeiter. I was chained on three continents, beaten, stabbed and starved. I went to war. I ran into enemy guns. And I survived …

THE passport was a masterpiece of the forger’s craft but, inside it, a time bomb was ticking. One of the visa stamps so carefully inked on to its pages in a Bombay backyard workshop had been stolen from a Sri Lankan consulate. The theft had been uncovered and passports bearing the stamp had been flagged on international customs computers. Deep down, the fugitive knew he should have ditched the passport, cut it up and burned it as he had many others as he slipped back and forth across national borders. But he had committed the wanted man’s fatal mistake of growing too fond of something to abandon it.

It was a thick British business ‘book’ with extra pages between embossed hard covers. He loved the heft of it, loved tossing it on the counter with the insouciance of the seasoned business traveller, pukka accent at the ready, confident the bored official would barely glance at it.

He had done it with scores of passports, identities and accents all over the world. This time he was travelling through Germany to Zurich on a drug-smuggling run from Bombay. He was used to Germany: he had spent so long there the previous year he had formed his own rock band and played in pubs and clubs. But as soon as the officer called him aside and the sniffer dogs did their job, he knew his past had caught up with him at last.

Frankfurt police took his fingerprints and flashed the information across the world. In just seven minutes they knew they had caught Australia’s most wanted man. It was March 31, 1990. He had been on the run nine years and 10 months, a quarter of his life.

Gregory John Peter Smith, the ‘Building Society Bandit’, alias ‘Chicken Man’, was back in the coop.

GREG Smith was an unlikely criminal. The road that led to a German prison cell – and his eventual return to Victoria’s Pentridge Prison – began in middle-class Melbourne where, as a child, he showed no outlaw tendencies beyond a vivid imagination.

He loved writing and recalls writing his first play when he was five, acting it out for his family. No one could have guessed then that the bright, polite little boy would grow up to lead a life any self-respecting novelist would hesitate to invent.

Happier days … Aubrey in jail, intact.

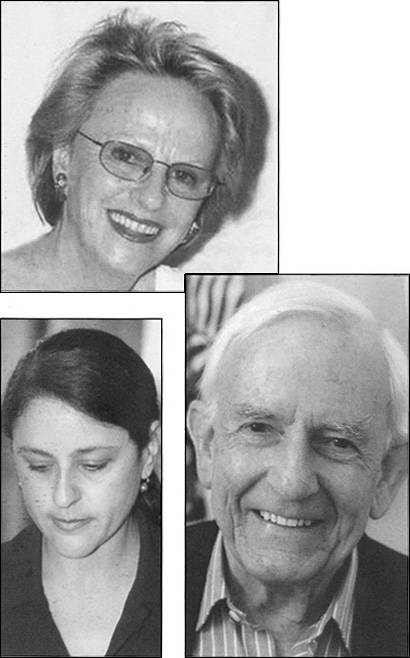

Money can’t buy you love. The main players in a middle-class tragedy: victims Margaret Wales-King and husband Paul, and the killer’s wife, Maritza.

The minnow of the Wales family – double killer Mathew.

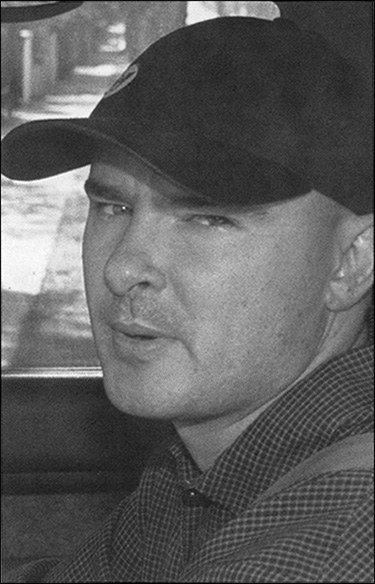

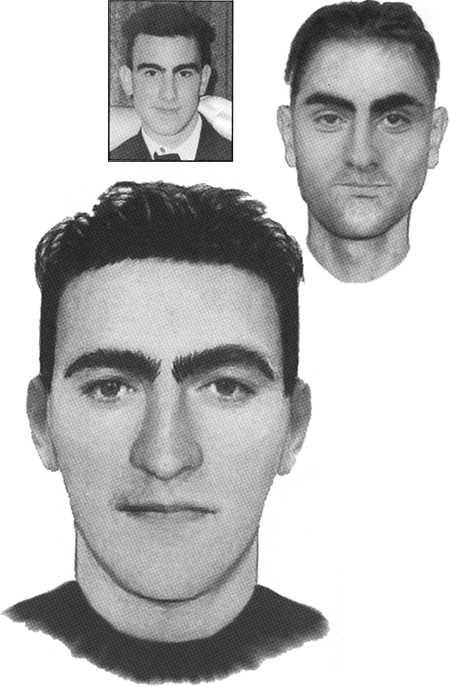

Snap. The many faces of police killer Jason Roberts. Above, the 1998 robbery identikit that put him in the frame. Left: the police ‘computer image’ that put him in the bin.

Roberts’ driver’s licence photograph.

Ian Silk

Gary Silk

Peter Silk

Rod Miller

Carmel Miller

Bandali Debs

Jeremy Rapke, QC

Graeme Collins

Jason Roberts

Paul Sheridan

They bet they could stop him. They lost. Fred ‘The Cat’ Silvester after raiding another backyard bookie.

His mother, from an old Melbourne family of academics, actors and architects, had married young and unhappily. Greg, the elder of two boys, basked in what he would later call ‘the high sierra of my mother’s love’ but hungered for his absent father’s approval, which never came. It was a psychic scar that would take decades to heal, though father and son were to make their peace not long before the old man died.

The boys grew up surrounded by books and ideas and interesting people from all over the world, but not much money. Their mother, a Fabian socialist, worked hard to send them to Parade College, a Christian Brothers school, but imbued them with her own radical politics. Greg had the ability to enter the professions or academia but social and political causes burned too bright for him to concentrate on study. Always willing to stand out from the crowd, he was a rebel looking for a cause – and he found too many.

There was a reckless physical side to him that marked him apart from most clever kids. Because they lived in poorer suburbs, he and his brother were targets for local louts because of their church school uniform. Greg went to boxing gyms and karate classes and never backed away from a fight. He had plenty of them between the bus stop and the front gate. This willingness to have a go became a defining characteristic. He preferred rugby union to cricket and Australian Rules because he saw something pure in the brutal chivalry of the game. But, most of all, he was drawn to the politics of protest: the combination of the intellectual and the physical was irresistible.

At 18, he had married his girlfriend, a teaching student. He left school a year early and worked in factories to support her and their baby daughter. Later, he went to night school, excelled, and got into Melbourne University while working as a sheet metal worker in Thomastown. It could – perhaps should – have been a turning point, but it didn’t work out that way.

Where many in the protest movement were content to mouth slogans, smoke joints and talk revolution, Smith loved the adrenaline rush of direct action. He wasn’t alone there, of course. There were the usual suspects – malcontents drawn by the promise of excitement, the whiff of danger, perhaps the chance to hurt someone or exact some sort of revenge on a world that they thought had somehow shortchanged them. But Smith, like few of his contemporary student radicals, stood out because of his intelligence, charm, organisational ability – and the practical skills and knockabout attitudes he had picked up while working for a living. While others talked about workers’ rights, he had been a welder and driven trucks.

He became an anarchist, joining other fringe groups in battles with police. As such, he got on well with militant unionists, even learning to make bombs at a clandestine ‘school’ in a container on the waterfront, a skill he was later thankful he never used.

To younger students there was a touch of Che Guevara about the motorcycle-riding martial artist with the thinker’s quick brain and the worker’s brawny biceps. Contemporaries remember him as a constant presence in the Melbourne University ‘caf’ scene, holding court at his regular table, often with his little daughter in tow. But while he was trying to save the world, he lost his marriage. His wife went overseas with someone else. He looked after their daughter for 18 months – until the child’s mother returned and won custody of her.

As Smith tells it, his world crumbled. He could not accept losing his daughter. He slid into a malaise, losing interest in studying philosophy and drifting from job to job. In 1975 he was alone in a rented house, so depressed that when a casual acquaintance dropped in and produced heroin and a syringe, he accepted. It was the wrong turn in a life that could still have gone either way.

He had always despised heroin because he believed it exploited people. But he didn’t fear its addictive power – and he should have. ‘That first hit made me an overnight junkie,’ he was to say a lifetime later. ‘With heroin in my veins, all guilt, pain and sorrow was gone. By the end of 1977 I’d been through a methadone program. I’d sold everything, called in every favour.’ Ashamed at sponging off family and friends, he says, he did the second most stupid thing of his life.

He went to a hobby shop and bought an imitation pistol. He could have taken money from the car dealer where he was working, with no danger, but some twisted sense of honour stopped him. In his drug-fevered and still adolescent mind, he thought he wanted to risk being shot: that the danger he was in somehow made up for the crime he was committing. He now shakes his head at that crazy kid. ‘I didn’t realise then what a gutless, cowardly thing it was to wave a gun in someone’s face,’ he was to say. That, and his mother’s distress, would become his deepest regret.

The boy who liked to write stories had become a heroin addict with a Ned Kelly complex, a toy gun and a death wish.

THE first robbery was at a city cinema, on the same day, he says, that he had been refused treatment at two methadone clinics with long waiting lists. He was loitering nervously, waiting for the foyer to empty, when he smelled smoke near the men’s toilet.

‘I went in and the waste paper bin was on fire because someone had dropped a butt in it. I put it out. The ushers came running down, scared the place was on fire. I told them I’d put it out and they thanked me and went back into the theatre.’

The girl behind the ticket counter seemed relieved that the thin stranger in the cap and sunglasses had been so helpful. When he approached, she smiled – right up until he produced the pistol. I’ll never forget the shock on her face,’ he was to say. ‘I apologised and said I was a junkie and that I needed the money. I decided if I ever did it again I would look people in the eye with no disguise, speak gently and not frighten them.

‘I bolted into the street and literally ran into two cops around the corner. I dropped the hat, the sunglasses and the money on the footpath. I knew that any second they would get a radio message about the robbery. I said “Sorry, officers. I just closed my business late and my wife has been waiting for an hour and she’ll kill me. She’s a real dragon.” They laughed and picked up the money and handed it to me. I never ran from a robbery after that.’

Twenty minutes later, exhilarated and ashamed, he was scoring heroin in St Kilda. Something had changed forever: ‘I’d crossed the line. Your life as a decent human being is over. A chill enters your heart that even heroin can’t warm.’

He did the first building society a few weeks later, on December 8, 1977. Newspapers reported next day that a man in a grey suit had entered a building society in the Hub Arcade in the central city business district about 3.30pm, carrying a briefcase and a rolled-up newspaper. He pointed the paper at a teller, who saw a pistol hidden in it. He politely asked her to put cash in the briefcase and got $10,621 – in those days about two years’ factory wages.

Eight days later, the same well-dressed man walked into a Collins Street building society just on closing time, waited quietly, then produced the newspaper and gun and took $11,000. Meanwhile, the front door was routinely locked by a staff member who hadn’t noticed the little drama at the tellers’ counter a few metres away. The robber calmly unlocked the door and vanished into the peak-hour rush.

In nine weeks the same polite, unmasked man robbed seven building society branches eight times, netting a claimed total of more than $32,000. His eighth robbery was the second time he had struck one branch in four weeks. ‘Hello, ladies, it’s me again,’ he said to an incredulous teller, who noted he had changed his suit for smart casual clothes and his hair colour from red to blond. On one occasion, he claims, the amount allegedly reported missing by the branch manager was twice as much as he had taken. Someone else had taken the opportunity to cash in on the robbery.

Police released Identikit pictures of the bandit, dubbed ‘Mr Cool’ by newspapers. But it wasn’t an alert citizen who nailed him. He believes it was his drug dealer, trading information to avoid being charged himself. The official version is a little hazy but one thing is certain: a crew from the armed robbery squad turned up on February 22, 1978, at Mount Macedon, a pretty retreat about an hour’s drive from Melbourne. Ironically, he had gone there a day earlier to go ‘cold turkey’ at a relative’s holiday house. He was driving a Holden Monaro worth about $2500. The other $30,000 had mostly gone up his arm – and other people’s. Junkies with money always had friends to help spend it. And heroin was ruinously expensive then.

A detective helpfully drove the prized Monaro back from Mt Macedon. Smith never saw it again.

At Russell Street police headquarters, they handcuffed him to a desk. He was so ill from heroin withdrawal that a doctor ordered him to a methadone clinic before the interrogation could continue. He says he agreed to talk to keep pressure off a female friend who had been arrested. Police who were present are vague about the details, but the result was that he admitted the eight building society raids and 16 smaller ‘jobs’ as well. After robbing a suburban chicken shop, the Chicken Inn, and escaping in a taxi, he had been dubbed ‘Chicken Man’, and the name stuck.

A leading defence barrister, now a Supreme Court judge, advised Smith to plead not guilty. He refused, saying he couldn’t face people he had robbed and then deny it. He was sentenced to 23 years, later reduced on appeal. Even the police were embarrassed by the sentence’s severity, he recalls.

Career crooks who shot people with real guns got lighter sentences. But, unlike him, they didn’t have a Special Branch file.

INSIDE, they called him ‘Doc Smith’, the name he had on the streets. He had done a first aid course and previously saved other addicts from overdoses. Now he helped prisoners who had overdosed or been injured in jail ‘accidents’, which were common. Because of his willingness to fight back he won several beatings from prison officers – but grudging respect from the hard men who effectively ran Pentridge.

He taught one to read and write. In return, the crim showed ‘Doc’ how to build up his scrawny 57-kilo addict’s frame by lifting weights, a necessary precaution even for an armed robber with some ‘dash’. It was a good reason for him to stay away from heroin. ‘Pumping iron’ would become a lifetime habit. It is, he wrote later, ‘Zen for violent men’, the only self-discipline some of them know.

The former philosophy student struck up an unlikely rapport with a notorious ‘lifer’, William O’Meally, a convicted police killer, escaper and the last prisoner officially flogged in Australia.

O’Meally, then almost 60, was the prison barber, which let him move freely around the jail. He told Smith he was going to be paroled and said he would recommend him for the coveted barber’s job. He added, meaningfully, ‘You’re doing life and it will be good for you to get around where you can look up.’ Smith was puzzled. O’Meally repeated himself with some emphasis and Smith realised the old crim was giving him a chance to set up an escape.

He took the barber’s job, to the relief of younger prisoners who dreaded O’Meally’s rough and ready haircuts. As a hair stylist, Smith was more modern but had a limited range: he gave every prisoner the David Bowie ‘Ziggy Stardust’ look.

So he took O’Meally’s job but would he take the hint about escaping? With a reduced sentence, Smith faced from 10 to 14 years inside, which meant he would be out in his late 30s. It was a long time, but bearable. It was only after being put in ‘the slot’, the infamous H-Division punishment cells (because, he says, of a not-so-secret love affair with an actress visiting the prison to teach drama), that he decided to risk escaping.

As he tells it, he was so badly beaten in H Division by a handful of rogue warders that he was sent to St Vincent’s Hospital with broken ribs, a smashed cheekbone, broken nose and multiple cuts and bruises. He refused to ‘lag’ the officers responsible but feared he might be killed or crippled if put in H Division again. When the doctors asked what had happened, he played the game, replying: ‘Fell out of bed, sir!’ When asked if he could explain why he had so many separate injuries he said, deadpan: ‘Fell out of bed several times, sir!’ Jail etiquette demanded this charade.

After the hospital stay, prison officers thought he was a changed man. He acted docile – and frightened – around the bashers in uniform. ‘I went to one – a big, cruel man – and asked him not to hurt me any more. He went around boasting that he’d broken me.’

It worked. Soon he was allowed join a maintenance crew with a young killer called Trevor Jolly, who was already secretly planning to escape. They persuaded their overseer, a rugby player who liked the way Smith played the game in the annual prisoners v. officers match, that they should build a rock garden near the main gate, where builders were renovating an office building.

Smith faced a choice. ‘I knew I’d lose my family, my name, even my country, because I would have to leave Australia. Later, I realised you lose your friends, your date of birth, your nationality – everything that gives you an identity gets erased. On other hand, it’s liberating, a chance to reinvent yourself.’ He decided to do it – the one offence he doesn’t regret.

He was to write about it this way:

‘I escaped from prison in broad daylight, as they say, at one o’clock in the afternoon, over the front wall and between two gun towers. The plan was intricate and meticulously executed, up to a point, but the escape really succeeded because it was daring and desperate. The bottom line for us, once we started, was that the plan had to succeed. If it failed, the guards in the punishment unit were quite capable of kicking us to death.

‘There were two of us. My friend was a wild, big-hearted twenty-five year old serving a life sentence for murder. We tried to convince other men to escape with us. We asked eight of the toughest men we knew, all of them serving ten straight years or more for crimes of violence. One by one, they found an excuse not to join in … I didn’t blame them. My friend and I were young first offenders with no criminal history. We were serving big years, but we had no reputation in the prison system. And the escape we’d planned was the type people call heroic if it succeeds, and insane if it fails. In the end, we were alone.

‘We took advantage of extensive renovations that were being carried out on the internal security-force building – a two-storey office and interrogation block near the main entrance gate at the front wall. We were working as maintenance gardeners. The guards who pulled shifts in the area saw us every day. When we went to work there, on the day of the escape, they watched us for a while, as usual, and then looked away. The security-force building was empty. The renovation workers were at lunch. In the few long seconds of the little eclipse created by the guards’ boredom and their familiarity with us, we were invisible, and we made our move.

‘Cutting our way through the chain-link fence that closed off the renovation site, we broke open a door to the deserted building and made our way upstairs … There was a manhole in the ceiling on the top floor. Standing on my friend’s strong shoulders, I punched out the wooden trapdoor in the manhole and climbed through. I had an extension cord with me, wrapped around my body under my overalls. I uncoiled it, fixed one end to a roof beam, and passed the other down to my friend. He used it to climb up into the roof space with me …

‘We scrambled towards the narrowing pinch of space where the roof met the front wall of the prison. I chose a spot on one of the troughs to cut our way through, hoping that the peaks on either side would conceal the hole from the gun towers …

‘With a cigarette lighter for a lantern, we worked to cut our way through the double thickness of hardwood that separated us from the tin on the roof. A long screwdriver, a chisel and a pair of tin snips were our only tools. After fifteen minutes … we’d cleared a little space about the size of a man’s eye.

But the wood was too hard and too thick. With the tools we had, it would take hours to make a man-sized hole.

‘We didn’t have hours. We had thirty minutes, we guessed, before the guards did a routine check … In that time we had to get through the wood, cut a hole in the tin, climb out on the roof, use our extension cord as a rope and climb down to freedom. The clock was ticking on us. We were trapped in the roof … any minute the guards might notice the cut fence, see the broken door and find the smashed manhole.’

They couldn’t go back and pretend it hadn’t happened. The attempt to escape would be obvious – enough to earn them a year in ‘the slot’, where they feared random and brutal beatings. Sweating with fear, they racked their brains for options. One was to steal a ladder, tie the cord to it and rush the wall, knowing one or both of them would probably be shot. Then Smith remembered seeing a buzz saw a builder had left on the ground floor. Using it to cut a hole in the timber roof lining would mean taking the chance that the guards would think it was the builders using the saw. But it seemed worth the risk.

There was one problem. There was no power inside the gutted building. The only live socket was outside.

Smith would have to go outside, in view of any guards who were looking, to plug in the cord. He sneaked a look. Guards were chatting with each other just twenty metres away, so he darted out and got away with it.

Back in the roofspace, they plugged in the saw.

‘I took the lighter and held it for him,’ Smith was to write. ‘Without a second of hesitation, he hoisted the heavy saw and clicked it to life. The machine screamed like the whine of a jet engine … Then he drove the saw into the thick wood. With four swift, ear-splitting cuts, he made a perfect hole that revealed a square of gleaming tin.

‘We waited in the silence that followed, our ears ringing … hearts thumping. After a moment we heard a telephone ring close by, at the main gate, and we thought we were finished. Then someone answered the phone … We heard him laugh and talk … It was okay.

‘I punched a hole in the tin with the screwdriver … then used the tin snips to cut a panel of tin around three sides.’

Their escape hole was in the roof valley – a trough that was out of sight of guards in the gun towers. But the ordeal was far from over. They needed to retrieve the power cord – it was now going to be their rope. Smith went downstairs but he couldn’t force himself to take the risk a second time of going outside to unplug the cord. He took a chisel and drove it through the live cord, taking the chance that it would blow a fuse and automatically activate some alarm. It didn’t.

He grabbed the loose end of the cord and rushed back upstairs, tied it to a beam. They squeezed through the hole onto the roof and wriggled to the bluestone battlements of the outside wall to sneak a look outside. There was a queue of delivery vehicles waiting to get in, and a lot of people.

Jolly wanted to run the risk of going over the wall and running the gauntlet of the people below. Smith persuaded him they should wait. Which they did, for twenty five minutes. When the street emptied, Jolly went first, sliding down the cord to freedom. Then it was Smith’s turn.

‘I clambered over the bluestone parapet, and took hold of the cord. Standing with my legs against the wall, and the cord in both hands, my back to the street.’ He looked at the gun towers on either side of him. Each guard had an automatic rifle slung over his shoulder, but each was preoccupied – one talking on the telephone and the other calling to another guard inside the prison yard. It was the moment of truth.

‘I pushed off with my legs and started the descent, but my hands slipped … and I lost the cord. I fell. It was a very high wall. In desperation, I grabbed at the cord and seized it. My hands were the brakes that slowed my fall. I felt the skin tear away from my palms and fingers. I felt it singe and burn. And slower, but still hard enough to hurt, I slammed into the ground, stood, and staggered across the road. I was free …

‘I looked back at the prison once. The cord was still dangling over the wall. The guards were still talking in their towers … I turned my back. I walked on … into a hunted life that cost me everything I’d ever loved.’

It was the first day of the rest of his life.

TREVOR Jolly was caught within weeks, but Smith vanished. Much later, postcards would arrive at Pentridge from around the world. They weren’t signed but everyone inside knew they were from Doc Smith, the one that got away. He became part of prison folklore. Young prisoners who never knew the man himself knew who he was and what he’d done.

But such hollow notoriety among the the bad, the mad and the sad was no comfort for Smith’s loved ones. At every Christmas dinner for nine years, before news of his capture in Germany, his mother would set a place at the table for the son who dared not contact her directly. And his brother Nick, a musician of note, would raise a toast to him, and they would pray he was well. For a long time, they did not know how he had got out of Australia or where he was.

Therein lies a story. Several, in fact.

Before the escape, Smith had saved a young prisoner’s life when a prison card game turned murderous. Smith knew that a violent, dimwitted prisoner was planning to kill the youngster, who had rashly angered him by questioning the way other prisoners let him ‘win’ tobacco in a regular card game. Smith talked the prisoner out of killing the youth. Later, during a prison visit, the grateful young prisoner introduced Smith to his older brother, who was the leader of a motorcycle gang. Which is why Smith called in the favour, arriving (with Jolly) at the biker’s home in a southern suburb just hours after escaping.

The biker was as good as his word. He gave them money, guns and a safe house. At first, they intended to play the conventional criminal card and pull a big robbery to finance life on the run. But, after two weeks in hiding, Smith felt a compulsion to visit a philosophy lecturer he had known and respected at university.

The urge was so strong that he risked capture by going across town to La Trobe University, where the academic worked, carrying a gun in a sports bag. The lecturer urged him to ditch the gun, to forget robberies, to split with the other escaper and avoid all criminal contacts. ‘He said if I didn’t that I would regret it. At the time I thought he was mad but I pretended to agree.’

Outside the lecturer’s office, a student recognised him. He had seen her looking at him in the university canteen earlier. Now she was hanging around, as if she hoped to catch his eye.

He was hoping to slip away, to take his chance in the underworld, but the student would not be deterred. She approached him. ‘You look as if you need help,’ she said with meaning, staring at his hands, which were swollen and torn from sliding down the extension cord on the prison wall. He could either run – or trust her. He trusted her. She led him to a nurse for treatment, then took him home and introduced her housemates to one of Australia’s two most-wanted men.

Smith took it as a sign to heed the lecturer’s advice to abandon the criminal world and trust people from his previous life: providing they liked him, there was less chance of detection with them because they were not by nature as treacherous as many criminals were, and the police would have no reason to approach them and no leverage over them.

The underworld is a small, incestuous and dangerous place for a wanted man and, by following his intuition, he could stay out of it. He decided to keep it that way. After leaving the friendly students, he spent a night at a well-known woman writer’s house not far from Melbourne University, then visited Norm ‘The General’ Gallagher, the leader of the Builders’ Labourers Federation. Smith knew Gallagher from his protest days, when he had forged close links between workers and students. He decided it was worth the risk of going to Gallagher’s union office, although it was virtually within sight of Russell Street police headquarters.

Gallagher, a sometime heavyweight boxer who had done jail time and would later do more, growled a greeting – ‘Look what the cat dragged in’ – then got straight on the telephone to a union organiser who was flying to Perth that night with a group of other union officials. Gallagher told the man to stay home and keep out of sight that night instead of catching the plane, explaining that someone else would be using his ticket. Smith joined the group, went to Melbourne airport with them and was on his way.

In Perth, a big BMW motorbike was waiting outside the terminal. The rider handed Smith a helmet.

‘He told me to hang on tight and said if the police started chasing us, to hang on tighter.’

In an hour he was in a union safe house with a family. He told them who he was and why he was there. In two weeks he moved into a house with six university students after answering an advertisement posted on a university notice board. The notice said the successful applicant would have to like smoking dope and loud music. He knew he would fit in, and did.

At the student house he befriended a visiting New Zealander, a welder who gave him his passport and driver’s licence. ‘I told everyone who helped me the truth, that I was wanted, but not one of them betrayed me. I found that if I trusted people, they trusted me.’

Smith had another routine. ‘Everywhere I went I washed the dishes. I’ve heard of wanted men being caught doing all sorts of things – but never heard of one being caught while washing the dishes.’ Besides, it was a good way to stay friendly with everyone. The last thing he needed was a housemate with a grudge. He was only ever one anonymous telephone call from being arrested.

Within six months he was in New Zealand. In Christchurch, he called himself Nick Freeman, one of many aliases. But his cover was blown when the local newspaper published a story on the ten most wanted men in Australia. Several people he knew recognised the picture of the desperate escapee, Gregory Smith, Melbourne’s missing ‘building society bandit’, as the friendly, well-spoken Aussie. He left town overnight and resurfaced on the North Island with a new surname.

Even his New Zealand adventures could fill most of a book – and will, one day. For some months he worked two jobs and played rugby in a team coached by a drug squad detective. And, although he linked up with political radicals, he steered clear of the criminal world. His best disguise was honesty, diligence and politeness.

One night, he recalls, ‘I was working night shift at a service station when a guy came in that I could tell was going to rob the place. Before he got to the counter I said: “Before you say a word, mate, take this $20 and put it in your pocket. And before you go down this road, I can tell you that I have, and it only causes grief. Is $20 enough?” The guy looked relieved. He said, “No, I need $45”. I gave it to him out of my own pocket and he left. I hope it saved him.’

Amazingly, he was twice locked up on minor charges, but managed to wriggle out of custody before his fingerprints filtered through the system. The problem was, though, that now the authorities knew he was in New Zealand, it would only be a matter of time before he was picked up. He had to go into hiding – and he had to get money to finance the next step of his plan, which was to get to Europe.

He had vowed never to do another armed robbery, so the choice was limited. He vanished again, hiding at a remote bush block in the north, where he spent months living like a hermit and growing a marijuana crop. When it was ready, he harvested it and hitchhiked south to Auckland, with a backpack full of the valuable and illegal cash crop. He got $12,000 for it. In late 1981, that was enough money to buy a modest house. But the fugitive wasn’t buying real estate. He got a false passport and an air ticket to Europe and had enough left over to support himself for a long time.

As it happened, the flight had a two-day stopover in Bombay. On an impulse, he decided to stay for a while. It was an interlude that turned into seven years …

What happened there is a story now being shared with readers all over the world.

THE man who used to be an outlaw named Gregory John Peter Smith is now neither. He changed his name by deed poll to Gregory David Roberts (his mother’s family name) when he was finally paroled in 1997, five years after being extradited from Germany – and has led a blameless life in Melbourne ever since. He does not swear, smoke, drink or take drugs, and is vegetarian. As for law-breaking, he would not even consider riding a bicycle without a helmet and, as always, helps little old ladies across the road. Not that he has gone to seed. He is 51, but with his angular face, fair hair swept into a long ponytail, and weightlifter’s chest and shoulders, he looks a decade younger.

Greg Roberts has rediscovered who he might have been if a personal crisis and heroin had not derailed his life at 23. His mother, who never lost faith in him, once told him he was ‘a good man who had a bad three months’.

He is ambivalent about his past. On one hand, he is determined not to be judged as just another ex-crook cynically cashing in on his notoriety – which is understandable, because he is obviously not just another ex-crook. On the other hand, he knows that interest in his past is the best way to attract the attention he needs to succeed in his chosen field. It is a tricky balancing act, but he manages it. ‘I don’t want to talk about my family or robberies in detail,’ he says gently. ‘My family and the people I robbed have suffered enough.’ He is careful not to try to excuse, let alone glamorise, robberies that he describes as ‘gutless and cowardly’.

The action man has become a thinker. Both instincts still live in him, although the impetuous one of youth is now governed by the meditative one of early middle age.

Had he stayed at university, saved his marriage and avoided heroin, he muses, ‘I would probably be a tenured philosophy lecturer by now.’ It is not hard to believe him. The man is a natural talker and a good one. Words flow from him, the pump primed by years of reading and discussion in a place where he had few distractions. Philosophy still fascinates him but it won’t feed him. Academic posts are scarce for someone whose study has been done in jail. So he has turned to his first love, writing. Even in his decade on the run, he kept journals and wrote stories. He had enough material for several novels – but writing the first one hasn’t been easy. His first draft was torn up by a Pentridge prison guard. He spent two years writing a second manuscript but it, too, was confiscated and destroyed in a petty display of power.

After his parole in 1997, he moved in with his mother and worked washing dishes in a St Kilda restaurant. In 1998, he rented a studio in Swanston Street, in the bohemian Nicholas Building, within sight of where he had committed the first robbery 20 years earlier, and started writing all over again. He was good at it.

He finished the first draft on New Year’s Eve, 2001. In the meantime, he wrote speeches, scripts and advertising copy for a living. Last year, buoyed by a publisher’s advance and his mother’s loyal support, he concentrated on a final draft. The result is an epic 385,000-word novel launched in Australia in late 2003, and in London and New York in the new year, part of an interlocking deal that will earn him a healthy six-figure sum over two years and has already attracted the attention of film makers.

Called Shantaram, the Hindu name that Indian villagers gave its author, it is the first volume of a trilogy. It begins with his arrival in India in late 1981 and ends before he goes to the Sri Lankan civil war five years later. He plans a prequel and a sequel that will tell the full story of his life before and after the Bombay years.

It is a novel. Some characters have been disguised or blended but he says the key events are real. He did live in a remote village for six months, then in the Bombay slums, where he treated the sick among some of the poorest people on earth. He did run black currency, forged passports and guns for the Bombay mafia. He also (probably) played bit parts in Bollywood films and published stories in a major daily newspaper under the nom de plume Nick Carroway – a play on the name of the narrator, Nick Carraway, in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s masterpiece, The Great Gatsby. And he almost died in Bombay’s toughest jail, where he was starved and beaten for four months without being charged.

At 930 pages, Shantaram is as thick as a housebrick but much more tender. It looks forbidding but grabs attention from the first sentence of a first page that is as striking as anything Fitzgerald wrote. It reads: ‘It took me a long time and most of the world to learn what I know about love and fate and the choices we make, but the heart of it came to me in an instant, when I was chained to a wall and being tortured.’

GREG Roberts could pass as a bouncer, bodyguard, a rock band’s road manager or a cleancut biker. But as soon as he speaks, the impression dissolves. To hear him, he could easily be the university lecturer he could and probably should have been.

He has an actor’s voice that is almost geographically neutral, the legacy of years on the run overseas. He speaks Hindi, Marathi and Urdu, taught himself to read and write German in jail to fight his extradition, has a smattering of French, Italian and Portuguese, and ‘just enough Swahili to save my life in Africa’. He smiles when he says this, but is not joking.

He is that rarest of people, a largely self-taught man who doesn’t sound like one. One moment he talks of literature, music and art. The next he drags up his shirt to show scars from the cuts inflicted with a split cane in his four months in Bombay’s feared Arthur Road Prison, where he was flogged by ‘convict overseers’. And where he saw men have both arms broken for daring to fight back.

After almost dying in the prison, and back on the streets without money or proper papers, he joined the Bombay-based crime cartel of an exiled Afghan warlord he calls Abdel Khader Khan. It was another turning point.

‘Until then I’d been no more than a desperate man, doing stupid, cowardly things to feed a stupid, cowardly heroin habit, and then a desperate exile earning small commissions on random deals,’ he writes. ‘I’d been a man who committed crimes, up to then, rather than a criminal, and there’s a difference.’

Joining the Bombay mafia meant learning money laundering and passport forgery. But the main reason he’d been recruited was to pose as an American for his Afghan leader on a mission to run guns to mujahideen rebels fighting the Russians. Because America was backing the rebels, his presence would help gain safe passage among the bandit Afghan hill tribes.

It was a nightmarish trip, he says, made on horseback. He claims several accomplishments but being a good rider is not one of them. His hands are bent and scarred from the frostbite suffered in the Afghanistan mountains, where he was hit with shrapnel from a Russian mortar and where several of his comrades were killed, including the leader he calls Abdel Khader Khan in the book. He still wonders why he survived while others didn’t.

AS Roberts tells episode after unlikely episode of his extraordinary life, a sceptic might wonder if it could all be true. His publisher, Henry Rosenbloom, certainly thinks it is, and for good reason. For Rosenbloom, well-known in Melbourne legal, literary and business circles, has had a private connection with Roberts’s family for more than 20 years and knew much of the fugitive’s story long before he offered to publish it.

It is difficult for Rosenbloom to talk about it on the record but he confirms that he knew in the 1980s, through a relative, that Roberts (then Smith) was hiding in Bombay.

Fragments of his extraordinary adventures filtered back to relatives and friends before his recapture in 1990. And soon after being recaptured in Germany, Roberts gave an account of his adventures to an Australian journalist (and Melbourne University contemporary), David Langsan, who visited him in prison in Frankfurt.

Langsan’s story, published in London and Australia the same week, tallies with the story Roberts has published thirteen years later.

There are dozens of anecdotes of life on the run but one stands out.

After recovering from his Afghan experience, Roberts smuggled currency and passports into Africa. Once, in a gun runners’ bar in Kinshasa, he sat down with five other hard men. The rules of the sinners’ club were simple: each man placed his weapons on the table beside a bottle of Jack Daniels, and told his tale in turn. At the end they would vote which story was best.

It was a tough audience. Each man had been imprisoned and had broken many laws. Most had killed people. They were smugglers, gun runners and mercenaries with prices on their heads, who used Zaire as a base because it was a rogue state.

‘My story was voted the best for two reasons,’ Roberts told the authors of this book.

‘First, I had escaped from a high security prison and they knew how hard that was. The other thing was that I had lived happily in a dirt-floor shack in the Bombay slums and run my own little clinic there, treating the people for everything from burns and rat bites to cholera.’

It was the sense of redemption that touched men who had much to atone for.

For Greg Roberts, that still matters. He is visibly moved as he recalls how that strange night in Africa underlines the one good thing he did in exile. In fact, redemption is the thread that runs through his story of good and evil, right and wrong, of choices made and chances grasped or lost.

He does’t claim any particular religion but admits to having changed profoundly since his days on the run. ‘I’ve written that it’s not what you’ll die for that counts, it’s what you’ll live for, from one year to the next.’

He pinpoints what he calls ‘the moment of maturity’ as being when he was poised to escape – or die in the attempt – from the Germans in 1991.

Terrorists he knew in prison there had organised a getaway car to be left outside the prosecutor’s office where he was taken monthly to discuss extradition proceedings.

He had a sharp wooden ‘knife’ made from a broom handle hidden in his papers and a rope and gag plaited from sheets under his shirt. While waiting to see the lawyer he intended to overpower, he knew that within minutes he would either be dead or on the run again.

‘Then I got this powerful vision of a policeman breaking the news to my mother. I decided then I could not make her suffer any more – that I would put someone else’s feelings ahead of my own. I changed at that moment.’ He resolved to serve out his time and resume the family life he longed for.

Which is what he has done. Now, with one book written, he’s working on a happy ending for the next one, telling how the bad guy changes into a good guy, gets the girl and lives happily ever after. But first he has to square his debt with fate. When the book royalties come, he says, he is going back to the slums of Bombay to set up a mobile medical clinic to help the poor people who helped him. ‘If I don’t do it, flay me,’ he says.