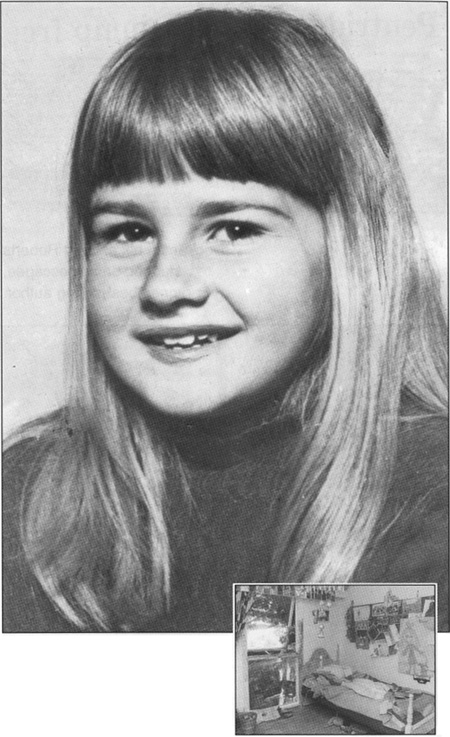

An empty bedroom and shattered dreams … decades later, the disappearance of Eloise Worledge still haunts.

‘I’ll cut off his finger if you like … would you like me to do that?’

WHEN senior police want results they usually turn to their most experienced detectives. Men who understand what questions need to be asked and have the criminal contacts to know where to get them answered.

But when Detective Inspector Paul Sheridan was given the hardest job in policing – to catch the killers of police officers Gary Silk and Rod Miller – he resisted the temptation to use veterans.

Lack of evidence and of any obvious suspects led police to believe they might be facing a lengthy investigation. The then head of the homicide squad, Rod Collins, told Gary Silk’s relatives that if there was not a breakthrough in the first two weeks it could take two years to solve the case.

He was one day off.

The final arrest – that of apprentice builder Jason Joseph Roberts – was on August 15, 2000. It was the day before the second anniversary of the murders.

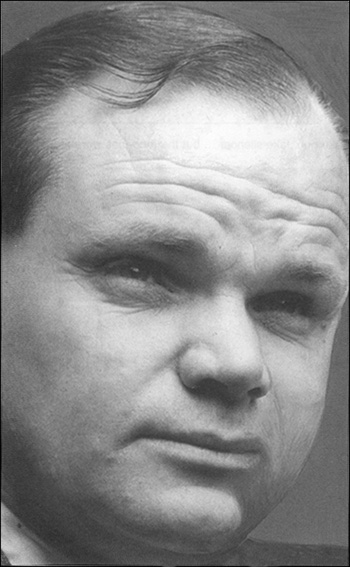

Sheridan, an experienced homicide squad investigator and a graduate of the FBI Academy, set himself for a marathon from the beginning. While he hoped for an early lead, he knew of similar overseas cases that had run five years.

As second in charge of the homicide squad, it would be his job to run the investigation. His deputy would be Detective Senior Sergeant Graeme Collins, also from the homicide squad. On the night of the murders, Collins was not supposed to work but the on-call crew had been assigned a suspicious death in suburban Melbourne. Collins and his crew were then moved up to on-call status.

The suspicious death turned out not to be a murder but, by then, the back-up team was already at the scene of the police double killing. Sheridan had seen Collins work at close quarters and was happy to have the experienced homicide man take a pivotal role. For Collins, a family man with a ready laugh and a thick moustache, the Silk-Miller murders would consume him for more than four years.

To try to keep some balance in his life, he would goal umpire for his son’s junior football side every Sunday. Few at the suburban grounds knew that the man in the battered white coat had been assigned one of the most important jobs in policing. Collins found another outlet from the drama and drudgery of the long-term investigation.

A keen art lover, he would continue to take watercolour-painting classes. Yet after the investigation was completed and the taskforce disbanded, he would find it difficult to pick up his artist’s brushes again.

As for Sheridan, he is no stereotype career policeman, either. He is a team man who still likes to be an individual, often preferring a dapper sports coat to the mandatory dark suits that tend to be the unofficial plain-clothes uniform of the modern detective. Not particularly big in a profession still dominated by large-framed men, he demands respect through intellect and logic rather size and bluff. An original thinker where some prefer to follow well-worn paths, he can be determined to the point of stubbornness.

When Sheridan set up the taskforce, many advised him to rely on detectives who had proved themselves under pressure. But Sheridan wanted young guns, not old hands.

He reasoned that if the investigation were to run for months and years, energy and stamina would be more valuable than experience and rat-cunning. Old detectives may have contacts but they are set in their ways. He wanted police who could think laterally. In football terms, young players chase hard while old players sometimes look for easy kicks. If his team took shortcuts, he reasoned, the odds of solving the case would plummet.

There was no shortage of volunteers. Hundreds of police wanted to help catch the killers. In the first few days, highly-trained members of the Special Operations Group turned up at the office just to answer the phones. They would have a more important and dangerous role to play much later.

From the beginning there was pressure on Sheridan to ‘make a statement’: to launch a series of raids on known criminals to show that police would not accept the killing of two of their own.

But he was more the chess player than the prize-fighter. The only statement he wanted to make was one under oath in front of a Supreme Court jury after his team had found the offenders.

From the beginning, the investigation had two main arms.

The two police had been murdered on stakeout duty outside the Silky Emperor Restaurant in Moorabbin as part of an operation to catch two prolific bandits.

Logic suggested that Silk and Miller had pulled over the armed men as they were about to commit the robbery and were shot dead to avoid arrest.

It seemed simple.

Find the bandits, who were suspected of being linked to an estimated 38 robberies since 1991, and you would find the killers.

Sheridan mostly selected young investigators with homicide experience but, suspecting that his targets were also bandits, he also recruited a team of armed robbery squad detectives, under the dogged Detective Sergeant Mark Butterworth, to join the taskforce, which was codenamed Lorimer.

But the armed robbery squad had been frustrated for months in their hunt for the stick-up team. Habitual bandits are usually career criminals, yet no police recognised the distinctive methods of the wanted men. If, as the theory had it, the killers were also robbers, then it looked as if they were not from known gangs. This turned up the degree of difficulty several notches.

For a start, underworld informers usually point towards likely suspects, but no one knew who was doing the robberies.

This led the police to profile the robbers as the type that were the most difficult to identify – an independent crime cell. A self-sufficient team of ‘loners’ who did not associate with other criminals and lived seemingly normal lives in mainstream society.

The profile indicated they probably worked in regular jobs and were not even suspected by their neighbours of being dangerous. Nearly all the robberies were in Melbourne’s outer east, leading police to suspect the men lived in the area, possibly in the region of Dandenong, Cranbourne and Narre Warren.

But who were they?

The second lead was glass at the scene found to be a match of a rear windscreen of a Hyundai five or three-door Excel. Police believed it had been shot out during the murderous confrontation with the two police.

After visiting the car manufacturer in Korea, forensic experts were able to narrow the number of potentially suspect cars in Australia from 35,000 to 2808.

And that was the second arm of the investigation. It appeared to be simple: find the car and you had the killers. But where was it?

Almost a year after the murders, an Australia-wide search had failed to identify the suspect car. Even though the taskforce had followed nearly 2000 separate leads, investigators were no closer to identifying the armed robbers who were likely to have killed Silk and Miller.

Despite attempts to remain positive, the investigation was in danger of stalling. Sheridan, a keen Carlton supporter who could see the parallels between team sport and taskforce policing, used former AFL premiership coach (and policeman) Alan Jeans to speak to Lorimer staff at a motivational breakfast. Jeans told them to believe in their methods and their colleagues and to persist. He told them in his trademark whisper-then-yell style that fear of failure was the rust that eroded commitment and endeavour. That once a team starts to think they can lose, it becomes self-fulfilling. He said the breakthrough would come not through luck or inspiration, but only through hard work.

Sheridan personally contacted the families of the victims every two weeks to keep them updated, but the reality was, there had been little to say for a long time. There had been too many leads that had turned into dead ends. Taskforce Lorimer was running out of time and information. In the previous months, investigators had gathered enough intelligence against six strong suspects to convince courts they should be allowed to bug telephones and plant listening devices.

But in each case, initial excitement gave way to disappointment. Police had checked every Hyundai in Victoria but could not find a match with the rear windscreen glass found at the crime scene at Cochranes Road, Moorabbin, on August 16, 1998.

Publicly, senior police remained supportive but, behind the scenes, some were losing faith, confidence and patience.

There was another, unspoken pressure on the Lorimer taskforce that was always just under the surface. Almost exactly ten years before the events of Moorabbin – on October 12, 1988 – two police constables, Steven Tynan and Damian Eyre, were ambushed and murdered while checking a stolen car in Walsh Street, South Yarra. Despite a massive investigation and a complex prosecution, the four men charged with the murders were acquitted in court. All young recruits at the police academy are told about the murders of Tynan and Eyre and the events of Walsh Street remain deeply ingrained in the collective psyche of the force.

To all members, from chief commissioner to junior constable, the thought of another double police murder for which the offenders escaped conviction was the stuff of nightmares.

There was talk of scaling down Lorimer or changing tack to introduce a ‘harder edge’.

Sheridan’s ideas might have looked cute on paper, but some thought it was time to kick down a few doors and loosen a few tongues in the old-fashioned way.

Chief Commissioner Neil Comrie had his critics in the job and was in an open war with the police association, but he never wavered over the Silk-Miller investigation. He refused to listen to those who entertained doubts and decided to press on, backing the taskforce against backstage critics and backdoor snipers.

In July, 1999, Sheridan ordered a review of all material held by the taskforce. In effect, he was prepared to begin again.

One of the most obvious steps was to review the phone records of all ‘persons of interest’.

One of those was Bandali Debs, a self-employed tiler from Cranbourne, who was identified as a promising suspect just ten days after the murders.

Debs had come under notice after police notified car-part suppliers and wreckers that they wished to speak to anyone who wanted a replacement rear windscreen for a Hyundai. On August 26, eight days after the shootings, a couple went to Grant Walker Parts in Bayswater to buy just such a window. The salesman jotted down the registration number of the Mazda they were driving. The car’s owner was Joanne Debs, Bandali’s daughter.

Further checks showed that his eldest daughter, Nicole, owned a Hyundai in the suspect class.

When police asked Nicole about the windscreen the following day she had first denied it had been broken. Later, she explained she lied because she didn’t want to get her father in trouble.

A car and a lie – it was a start, but only that. A seemingly relaxed Debs explained to police he had broken the window when he slammed the hatch shut on some of his tiling equipment. Forensic tests carried out three months later showed the car did not provide a match to the glass from the crime scene.

What’s more, police surveillance in the same month showed Debs was a hard worker who was up early every morning heading for work – not a lazy crook who did his best work at night.

Although Debs had a minor criminal record, police concluded he was a family man with five children just trying to make a living.

But the Lorimer review of Debs’s telephone records showed a tenuous link to the series of unsolved armed robberies and that made him a suspect, of a sort, in the Silk-Miller murders.

Police believed two bandits, a middle-aged man with a younger assistant, had robbed 28 targets between 1991 and 1994. All the robberies occurred in Melbourne’s outer east and, in most cases, the victims were tied up.

But on the pair’s last job, on October 9, 1994, at the Palm Beach Restaurant in Patterson Lakes, they had too many victims – seventeen diners and three staff – to tie them all up.

One of the diners was able to follow the gunmen and spotted the getaway car. Although he was menaced with a gun for his trouble, he was later able to provide police with a strong lead.

But an armed robbery operation, code-named Pigout, failed to identify the bandits and, after the close shave at Patterson Lakes, the bandits appeared to retire – for more than three years.

In 1998, there were 10 stick-ups that, to armed robbery squad detectives, appeared disturbingly similar to the Pigout raids. But police noticed one big difference. The older gunman seemed the same but his partner was cooler and more aggressive.

They speculated that the original younger robber had been scared off when he was nearly caught after the Palm Beach Restaurant raid and that the older man had recruited a fresh partner. A cocky one.

A new investigation, codenamed Hamada, was launched into the 1998 robberies and police identified a list of 60 possible targets, with ten highlighted as the most likely. The Silky Emperor on Warrigal Road was in the top ten. Gary Silk and Rod Miller were on stake-out duty as part of Operation Hamada when they were murdered.

Now, during the review of information by the Lorimer taskforce, police found a possible link via phone calls between Debs and a suspect for the early spate of robberies, tagged the Pigout raids by police.

It was was enough to warrant another look at Debs, the hardworking tiler.

Police had five separate target investigations into suspects identified by Lorimer. They were codenamed Crystal, Crimea, Doren, John and Pole. Now they had a sixth – Operation Solly.

According to Sheridan, the information was promising ‘but we weren’t too excited; we had seen strong leads before that had led nowhere.’

In November, 1999, police planted listening devices in Debs’s house in Springfield Drive, Narre Warren; in his Commodore station wagon; and in his daughter’s Hyundai coupe.

Within weeks, police found that the seemingly honest tradesman was an habitual and opportunistic thief. He stole anything that wasn’t nailed down, and sometimes things that were. He would loot building sites where he worked – taking cement, tiles, nails, and buckets, even hot water systems. If he couldn’t steal something at the time he would return at night to finish the job.

This was interesting, because the armed robbers the police were looking for were also opportunists. In one robbery on an Endeavour Hills chicken shop on September 27, 1992, a customer walked in with a late-night order. The two bandits tied him up with duct tape and stole $10. As well as taking money, they stole wallets, credit cards, mobile phones and cheap jewellery. At licensed restaurants they would take ouzo, whisky, Bacardi, Midori and Malibu, Cointreau, Jim Beam bourbon and beer. It was another possible link.

Police knew that Debs was a light-fingered thief, but was he a cold-blooded killer?

It was not so much that Debs was dishonest that interested Lorimer detectives. His foul and violent language suggested the tiler was living a double life.

Further telephone record checks showed that Debs had called a man in Ballarat on August 16, 1998 – just hours after the murders. The man in Ballarat had placed an advertisement in The Age and the Trading Post offering Hyundai parts for sale.

This didn’t tally. Because, according to Debs when he was first approached by police on August 27, he had smashed the rear window of the car with his tiling equipment on August 19 – three days after the murders.

There was enough new evidence for Lorimer investigators to ask forensic experts to re-analyse glass taken from the car. This time the results found that the glass ‘could not be excluded’ as the same type found in Cochranes Road.

Then why the initial confusion?

After losing the first rear windscreen Debs had fitted a replacement that had blown out, requiring yet a third window. It was later found that glass shards from the first two broken windscreens had been collected for examination, creating the initial false results.

This first window was clear, as were the pieces found near the Silky Emperor, while the first replacement was tinted. The initial tests, by pure fluke, contained fragments from only the tinted glass and gave a negative result. The second set of tests put Debs squarely back in the frame.

Debs bought the dark blue coupe as an 18th birthday present in June, 1997, for his eldest daughter, Nicole, who was living with Jason Joseph Roberts in Merrijig Drive, Cranbourne.

In October, 1999, taskforce armed robbery specialist, Detective Sergeant Mark Butterworth spotted a photograph of Roberts in the Lorimer office as part of a cluster of pictures of Debs and associates. He immediately saw striking similarities with a face image from the robbery of the Sportsmart shop in Noble Park on Sunday, March 29, 1998.

In that robbery, right on closing time, the older gunman yelled, ‘I’ll kill if I have to’ and then, with a reference to a US school shooting in which five people had died four days earlier, he said: ‘I’ll make Arkansas look like a picnic.’

One customer had her two-year-old daughter with her. The bandits made the mother lie on the floor and trussed her up with the child in her embrace, immobilising both of them.

But one woman in the robbery felt she could pick the younger robber. Olivia Coffman worked at the shop and told police that when she had gone outside to move her car she had seen the younger gunman before he had put on his disguise. She had assumed he was a customer but when she returned and walked in on the robbery he was wearing a stocking mask so sheer she could still see his face. She told police that despite the seriousness of the situation she felt like laughing at the comical Woody Allen nature of the stick-up.

She helped produced a police impression of the bandit. It was this likeness that struck Butterworth as being a match with Roberts.

He compiled a photoboard of pictures of young men that included the driver’s licence of the suspect. Coffman picked Roberts without hesitation.

Now detectives had a link between Debs and a suspect from the first set of robberies and Roberts, now a suspect for the 1998 raids. Debs and Roberts also lived in the Narre Warren area, right where police profiling had indicated the robbers probably lived.

DETECTIVES constantly fight for resources. There is never enough time, staff or equipment. Police learn early in their careers to make do.

The armed robbery squad sometimes takes perverse pleasure in managing to get by and do their investigations without assistance. Sometimes when a job is running hot they can’t wait for surveillance units or the Special Operations Group to be available. Over the years they have become adept at DIY policing.

In 1998, two armed robbers began raiding smaller targets in Melbourne’s east. Their pattern was strikingly similar to the team that had struck 28 times in 1991-94.

The Hamada investigation into the 1998 robberies began as just another job for the armed robbery squad but, as the bandits became more arrogant, they were soon high on the squad’s list. In what would turn out to be their tenth and last armed robbery, the bandits hit the Green Papaya Chinese restaurant in Canterbury Road, Surrey Hills, on July 18.

This time they wore President Reagan and Nixon masks but the routine was the same: taping their victims and taking anything they could, including a $250 bag of coins and a six-pack of cold beer.

One turned to his tied-up victims and as he was about to leave left a message for the detectives who would soon arrive. ‘Tell the police that Lucifer was here.’

It was an act of bravado that did not go down well with the armed robbery squad. Ray Watson, then head of the ‘Robbers’ is renowned for his sense of humour, but he could see nothing funny in bandits with guns traumatising victims and taunting his detectives. He called his team together and told them in simple terms he expected these men to be caught. Soon.

Police had profiled the bandits as well as they could but there were glaring holes in the picture. They tried to work out where the bandits might strike next, using computer-enhanced geographic profiling. The plan was to beat them to the next target and catch them in the act.

The bandits liked to work in Melbourne’s eastern suburbs, raiding restaurants and fast food chains around closing time and at weekends. They usually struck in areas close to main roads so they could make an easy escape.

For a few weekends after the Green Papaya raid police began to sit off likely targets but, while they did manage to arrest some would-be-bandits about to rob a Red Rooster outlet in Clayton, the Hamada gunmen remained free.

Senior police decided to enlarge the stakeout job – a 26 per cent jump in armed robberies on soft targets in just two years made it a priority. This time the ‘Robbers’ could not complain about lack of resources. They asked local police to compile lists of likely targets and eventually settled on a list of 60. The Silky Emperor in Moorabbin was seen as particularly susceptible.

Isolated in an industrial estate, it was the only business in the area open at night. Sitting on busy Warrigal Road near Cochranes Road, it offered access to main roads and it had its own dimly lit off-street parking. It was a perfect Hamada target. But it was not the only one.

The bandits tended to strike every two to three weeks, so police believed the next armed robbery was likely to occur in early to mid-August.

Police planned to sit off all designated likely targets, a massive task involving five separate police districts.

On Friday, August 14, the huge static surveillance team was briefed at the Police Academy in Glen Waverley – the only police building in the area big enough to deal with the numbers needed for Hamada. While the police were ready, the bandits were not and, as on most police stake-out jobs, nothing happened.

The following night fresh police were called into the operation, including Sergeant Gary Silk, a popular career policeman whose larrikin streak, coupled with a dedication to duty, made him a favourite in any station where he had worked.

When ‘Silky’ was told he would be working stake-out duty as part of Hamada he declined the offer of extra staff to assist.

‘I’ll be right,’ he told his then boss, Senior Sergeant Steve Beith, ‘I’m working with Rod.’

Gary Silk and Rod Miller had not known each other long enough to become friends, but they had seen enough of each other’s work to know they would team well.

Both had been seconded to work at the Elwood Regional Response Unit. Silk was from St Kilda and Miller from Prahran. The RRU was seen as a bridge for young police to gain investigative experience before becoming detectives.

Silk, 34, was picked for the job because he was a trained detective with experience at St Kilda and the prison squad and could help mentor the staff. Miller was selected because he had already shown a flair for investigation.

‘It was quite apparent that Rod would make a gun detective,’ Beith would later say. ‘Gary was quiet until he got to know you and was very good at his job.’

Police in the RRU wore scruffy clothes and did most of their work on drug crimes but, because it was necessary to cover nearly 60 potential armed robbery targets, they were called in to help.

Silk was the senior man, with 13 years’ experience. Miller, who was a year older than his sergeant, had graduated seven years and one day before the Hamada stake-out.

That Saturday night, August 15, Silk and Miller were assigned the Korean BBQ in North Road, East Bentleigh, and given the call sign Moorabbin 404.

It was a routine job. So routine both men kept their bulky bullet-proof vests in the boot of their unmarked Commodore.

By 10.35pm the Korean BBQ had closed. Silk and Miller were told to cruise over to the Silky Emperor to back up Senior Constables Frank Bendeich and Darren Sherren in Moorabbin 403.

Silk and Miller parked in the underground car park of the restaurant while Bendeich and Sherren observed the target from a hardware shop across the road.

Just after 11pm a small car slipped into the car park and drove out again. Silk and Miller gave chase down Cochranes Road but lost the suspect at speeds well over 120km/h. Much later, police would find the driver was a small-time crook who broke into cars.

After losing the sedan, Moorabbin 404 cruised back into the hidden car park.

Just after midnight, a dark Hyundai hatch travelled slowly into the car park and then drove out again, followed by Silk and Miller.

This time there was no high-speed chase. The hatch turned left into Cochranes Road, followed by the unmarked Commodore.

The police pulled over the car under a broken street light about 150 metres from the intersection. Silk and Miller would have been on guard, but not alarmed.

The driver of the car had pulled over soon after the police flashed the blue dome light. It was logical to think that if they were the robbers, surely they would have made a run for it. In America, police are quick to draw arms on suspects but in a quiet street in Melbourne there would have seemed no need for cowboy tactics.

Moorabbin 403 slipped past the two cars and parked about 200 metres away in Capella Court, with the headlights off. They could see Silk had approached the driver, who was standing passively at the door of the Hyundai. Miller was near the rear passenger side of the car. It looked, to an outsider, as if the police were conducting a routine car check.

Then Bendeich and Sherren saw the unmistakable muzzle flash of gunfire. As the shots were fired the Hyundai drove off. The two police in Capella Court could have given chase but their first duty was to assist their colleagues. They reported ‘shots fired’ and drove back to the Commodore.

They found Gary Silk already dead, lying on the ground. He had been shot three times, including once in the skull from point-blank range.

Rod Miller was missing.

When the call goes out ‘Police in trouble’, units come from everywhere. This time the message was ‘One down, one missing.’ The scene was organised chaos as police began to hunt for clues, killers and a colleague. Uniformed police, the dog squad, detectives and the police helicopter were called in.

Miller, fatally wounded but still alive, had managed to run, walk or crawl back to Warrigal Road near the Silky Emperor. As police were trying to contain the crime scene, they heard him call for help.

‘Silky’s dead, Silky’s dead,’ Miller told one of the first on the scene, Senior Constable Glenn Pullin. ‘Help me, help me. Don’t let me die.’

But as he thrashed and twitched in agony while fellow police provided basic first aid, he still tried to help the investigation. ‘Two. One on foot … dark Hyundai … I’m fucked, I’m fucked … I’m having trouble breathing … get them.’

Miller had managed to fire four shots during the ambush but missed his killers although he might have left a telltale mark on the car that would be found years later. And evidence gathered from his jacket would posthumously help detectives find the gunmen. He was rushed to the Monash Medical Centre but died three hours later from a massive chest wound.

Police would later reconstruct the night as best they could. The most likely scenario was that Silk and Miller at first believed there was only one man in the car because the younger one was crouched down in the passenger seat. This would have made the policemen relax, as they knew the bandits they were looking for always worked as a pair. This lack of concern explains why they did not radio in the registration number of the car.

As they turned into Cochranes Road, Miller had activated the portable blue light in the unmarked police car. Silk, the senior man, pulled in behind the Hyundai.

Debs, the driver, hopped out and stood next the door. His body language was non-threatening. He looked like a man expecting a ticket rather than questions over a series of armed robberies.

The policemen expected to chat to the driver for a minute or two and let him go on his way. But, as they approached the car, they would have seen Roberts hunched in the front seat and, in a split second, everything would change. They would have realised there were two men who roughly fitted the Hamada profile.

Silk called on Roberts to get out of the car and moved him to a grassy verge on the side of the road. It was police procedure to get him out of earshot of the driver so that they could be questioned independently.

Both police still had their guns holstered and buttoned down. Silk stood about a metre from Roberts. He would have expected to ask a few questions as he had countless times before.

Miller began to head back to the police car to radio in the details of the Hyundai. If he made that call, Debs and Roberts were finished.

Roberts, still a teenager and the one, according to the police, who was supposed to be the less aggressive, stood there looking at Gary Silk, who was nearly twice his age.

As Supreme Court Judge, Justice Phil Cummins, was to say more than four years later: ‘You knew that the time for stealth and cunning and bluff was over. You knew that imminently the two officers would search you and your vehicle, and would find the apparatus of the Hamada robbers: handguns, masks or means of disguise, and tape for binding your victims. You had a choice: apprehension or murder.

‘You chose murder.’

Roberts fired from point-blank range with his .38 revolver, shooting Silk in the chest. Miller, caught between the two cars and lacking immediate cover, unbuttoned his revolver and fired at Roberts, but Debs had dived back into the car, grabbed his .357 Magnum and fired repeatedly through the rear hatch, shattering the glass and hitting Miller in the chest.

The policemen were no longer a threat, the road was clear and escape would have been easy, as Debs was already in, or near, the driver’s seat. Instead, he walked around to Silk, who was lying on the ground with his gun still holstered, and shot him twice – first in the pelvis, smashing a vertebra, and then in the skull, killing him instantly. According to Justice Cummins, ‘Then you both returned to your car and drove away. But not in panic. With deliberation. Slowly, so as not to attract attention.’

When homicide investigators arrived at the scene it appeared there would be no short-cut to the killers. As Miller and Silk had not radioed in the number of the suspect car there was no direct path to follow. Senior police at the scene were filled with anger and grief, but also with something even more debilitating – an overwhelming sense of pessimism. Seasoned and a realist, Sheridan fought against the tide to remain positive, hoping for a lucky break.

When Gary Silk’s body was finally moved, hours later, Sheridan glanced at the palms of the dead policeman in the hope he had scrawled down the registration number of the car on his hand before he was ambushed. There was nothing.

But the seeds of the killers’ eventual destruction was lying on the bitumen just metres from Silk’s bloodied body.

In a crime scene devoid of many obvious clues, the shards of glass on Cochranes Road were the one meaningful lead.

An expert from Windscreens O’Brien looked at the glass and confirmed it was from a Korean car – the Hyundai driven by the killers. Forensic experts carefully collected the glass and sealed it in an evidence bag.

BANDALI DEBS was born in Sydney on July 18, 1953, under the name Edmund Plancis.

His father, Silvester Weipnikowski, was just one of a series of live-in lovers and part-time partners for his mother, Helga Anna Rutherford. Edmund had a younger brother and sister.

As a teenager, he could not stand the men in his mother’s life and started to run away from home. He found a father figure nearby in a man who ran a local boarding house, Michael Bandali Debs – known as Malik.

Eventually, the older man adopted Edmund Plancis, who changed his name to Bandali Michael Debs and became known as Ben.

He moved to Melbourne and, at 26, married Dorothy. They had three daughters and two sons – Nicole, Joanne, Kylie, Michael and Joseph.

Debs had been a labourer and cleaner but, after two years on unemployment benefits, he started his own tiling business, ‘B&M Tiling’, in 1995.

He had a reputation as a solid tradesman and was used by the KFC fast-food chain. He learnt the stores’ operating system and when he and Roberts robbed the KFC store at Ashburton on July 5, 1998, senior staff suspected an inside job – but no one thought of the contract tiler. Later, he was allowed to tile in one of the stores after hours, dropping the keys into the local police station for safekeeping. Police listening devices planted in his home would hear him talking to Roberts about being in the police station and seeing posters of ‘our friends’.

In the Mooroolbark police station, where he dropped the keys, there were posters of the $500,000 reward for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the killers of Rod Miller and Gary Silk. Debs repaid the fast-food chain for the work by stealing frozen chickens just before Christmas, 1999.

Jason Joseph Roberts was 10 when his father died. He was living at home with his mother and younger brother in Cranbourne when he met Nicole Debs while they were both learning karate. He was only 17 when he became Nicole’s partner. He spent weeknights at home and weekends with her.

He had drifted through the building industry, working as a junior glassmaker and labourer before becoming an apprentice builder.

When Lorimer police started to look at Debs a second time they were surprised at his close relationship with his daughter’s live-in boyfriend.

They were constantly together at night. Surveillance showed they were involved in thefts and burglaries, stealing building materials and equipment.

They were observed casing possible targets and checking police movements, always looking for surveillance. Not once did they pick the police who were following them.

It is not unusual for entrenched criminals to recruit their sons for violent crime, but Debs freely confided in his daughters as well. He was no sexist – but he was an opportunist. On December 11, 1999, he spoke with his son, then 15, about his part-time work at Hungry Jack’s at Cranbourne. It was not the usual father-son chat about work and life.

This father wanted to know the layout of the store, security and where the money was kept. He was using his youngest son as a forward scout for a robbery. He said if he robbed the store, staff could get hurt. The boy expressed his dislike for the manager. The caring father replied, ‘I’ll cut off his finger if you like … would you like me to do that?’ The boy thought it was a fine idea.

If that wasn’t enough, Debs suggested his son be working at the store during the robbery. He would be made to lie on the floor and would be tied up. Then, the ever-helpful father said, the teenager could claim for crime compensation.

The conversation was a vital piece of intelligence. It showed Debs was more than a thief; he was a potential armed robber. He had access to a Hyundai, which was mysteriously damaged at the time of the murders, and he was a liar. The circumstantial evidence was such that even the conservative Sheridan was finally convinced they had found the killers.

There was one other little sweetener. Debs, the opportunist, had once done a small tiling job, ‘for a Chinese guy’. It was at the Silky Emperor.

Within days, four members of the taskforce went to the Silks’ family home in Mount Waverley to see Gary’s father, Morrie, who was dying of cancer.

Paul Sheridan went into the bedroom, knelt beside the bed and told him they had identified his son’s killers. Morrie died on December 28.

Just before Christmas, the investigators also told Rod Miller’s widow, Carmel, there had been a breakthrough.

Police recorded Jason Roberts talking of a robbery where one of the female victims thought it was a joke and refused to lie on the ground.

It matched – almost word for word – a statement from one of the victims of the armed robbery at the Green Papaya restaurant in Surrey Hills on July 18, 1998.

The listening devices showed how Debs was teaching his apprentice the lessons of crime. He told him to be aggressive on jobs and victims would ‘drop like spaghetti’.

It confirmed the police belief that the two were responsible for the 10 Hamada robberies and that the tiler was clearly the senior partner in all the jobs. It was a breakthrough, but the police case against the Debs and Roberts was still weak. They had a file full of intelligence connecting the men to the armed robberies but little to link them to the murders.

They had a few shards of windscreen glass that were not conclusive, no witnesses, and no inside sources. An undercover operation was unlikely to succeed because Debs confided only in family members – he would never talk to a stranger.

They needed evidence and the most telling would be from the mouths of the suspects themselves.

But how could they get them to talk?

IT WAS early in 2000 when Sheridan, the chess player, began to make moves designed to get his suspects to open up and talk so police could tape them. It would take more than six months to reach checkmate.

In February, taskforce police went to Debs’s brother, Robert Rutherford, in Sydney, and told him they wanted to talk to him about the police murders in Melbourne.

They also visited his natural mother. Like fishermen, they were throwing berley in the water in the hope of getting a bite.

Rutherford rang his brother and left a message that Melbourne police had visited. He refused to trust the phones and would not give any further details, but Debs’ sister-in-law rang and said ‘get up here quick’.

The police ploy worked perfectly – almost too well.

In the kitchen of his Springfield Drive home, Debs had a frank and brutal conversation lasting nearly an hour with daughter Joanne.

He told her: ‘Within the next six months, we’re goin’ to have to get rid of another two CPs (police)…to make the investigation spread … I think (the visit) is about the matter where two CPs have gone down. He (his brother) wouldn’t ring me under any other circumstance.’

He then raised the possibility of killing Carmel Miller and her baby son. ‘Seriously. Do you think I should get rid of the kid and the mother? … So they try and get the investigation to think that it’s drug related or anything like that.’

He referred to the guns being destroyed – one being cut up and the other being thrown in a lake. He said that at his mother’s house, ‘there’s stuff in the ground but they won’t find it.’

But they did.

Much later, police recovered jewellery stolen on June 8, 1998, from the Jumbo Restaurant in Blackburn, including a ring taken from the finger of one of the owners. A necklace and the ring were found buried in a builder’s bucket under Debs’ mother’s house.

The dutiful daughter did not seem shocked and often gave rudimentary legal advice – information gleaned from her Year 11 legal studies course at school.

She talked of police powers and correctly suggested that Victorian homicide squad detectives would not have jurisdiction in NSW.

She warned her father to be wary of police bugging equipment and advised him to use public phones or her sister’s new mobile to avoid intercepts.

Police were to say she became his father’s legal adviser and when she applied to work in the police department, Debs thought it was a good idea: it could be useful for the family, especially if she got access to confidential police files.

They discussed the idea that if Debs went ahead with his plan to kill two more police he should take back roads rather than the CityLink tollway to avoid police checking e-tag records.

Debs: ‘But I’m telling you now, if this continues like this on this matter, two CPs have got to go down somewhere, so the investigation goes stupid.’

Joanne: ‘Yeah, but where? It’s gotta be far, though.’

‘Debs: It’s got to be out of this area.’

Joanne: ‘Across the other side of the city.’

Debs: ‘On the other side of the city.’

Joanne: ‘That’s where it’s gotta be, though.’

The daughter told her father to wait. ‘But I don’t reckon there’s goin’ to be any need. Seriously, I don’t reckon there will.’

What Debs was planning was to kill police in another region to damage the Lorimer theory that the murders of Silk and Miller were connected with the Hamada robberies, all committed exclusively in Melbourne’s east.

Again, the theory of killing Carmel and the baby James was that it would skew the investigation away from the Hamada robberies link by suggesting that Rod Miller was a specific target rather than just a random policeman who had inadvertently run into robbers about to pull a job.

The father warned his trusted daughter: ‘Don’t say one word to your mother.’

Joanne: ‘Why?’

Debs: ‘Because your mother is fuckin’ nosy.’

Wife Dorothy seemed to know she was not the chosen one. ‘Oh yeah,’ she complained to Debs, ‘you talk to your daughter what’s going on but you won’t even fuckin’ talk to your wife.’

Sheridan faced an immediate dilemma. He wanted to unsettle Debs and Roberts so they would talk but he could not risk pushing them to the point where they would kill more police.

He was not ready to move, but the killers could force his hand at any time.

The Special Operations Group was put on standby and a unit moved to the Police Academy in Glen Waverley. Debs and Roberts would not be able to head out of their region to ambush police. They were now being watched around the clock.

Sheridan implored the specialists to make sure they took the men alive, but the SOG has not built its reputation by taking chances with armed police killers heading off to murder again.

On February 14, Sheridan rang Carmel Miller and asked where her son went to kindergarten. She instinctively knew there was a problem and asked: ‘Are we safe?’

Sheridan told her there had been some threats but that the taskforce would protect her. She had such confidence in the Lorimer team, she relaxed. ‘I knew I didn’t have to worry,’ she was to say later.

At first, the fact that Debs and Roberts were insular made the investigation difficult. They did not talk to outsiders so police could not recruit informers on the fringe to infiltrate the group.

But the family’s clan culture ultimately helped the investigation. Their conversations over the next weeks and months showed they were obsessed with the police shootings and they followed every development in the media.

This enabled Sheridan to manipulate them. In the months ahead the taciturn leader of Lorimer would go public. He would talk to the media in the hope of getting incriminating reactions from his suspects.

On February 12, Debs told his adoptive father, Malik Debs, who lived with the family, of his plan to kill more police, ‘I’m telling ya, another two have to go,’ but Debs senior disagreed.

‘No, you don’t go and do nothing.’

Three days later, he told Malik details of the double murder that only the killers could know: ‘When we drove in just to quickly look, they seen us so they drove behind us and … they stopped us. Then, it’s not good … A few shots. It’s no worries, a little thing.’

Debs spoke of what could only have been Miller’s actions after he was ambushed and shot that night. ‘Next to it, he was on the ground, laying on the ground, firing in the air, he was on the ground.’

By February, Sheridan moved more of the Lorimer team onto the investigation of Debs and Roberts. But some had to keep working on other suspects even though it was now obvious they were not the killers. They had to tie up the loose ends so the defence would not be able to unpick them in front of a jury. It was not enough to prove who did it. They had to show who didn’t. A brilliant Crown prosecutor, Jeremy Rapke, QC, was called in to review the evidence as it was compiled. Sheridan didn’t want to learn later of evidentiary problems when it could be too late.

While the case against Debs was looking stronger, they still needed more on Roberts. Sheridan used the media to try to divide the two men and isolate the master’s apprentice.

On May 29, Sheridan held a press conference and said police had an anonymous tip on the younger offender’s identity. ‘This is the most significant lead we’ve had in 20 months, there’s no doubt about that,’ he said.

Two days later, a clearly puzzled Debs told Roberts, Joanne and Nicole Debs: ‘No one was there but us.’

Police prepared a face image of the younger suspect – suggesting they wanted to know the person’s identity. In fact, the image was taken from Roberts’ driver’s licence. Sheridan released the image on July 16 – a quiet Sunday.

He had cancelled two previous press conferences because of competing news stories, including a coup in Fiji and the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax.

He was looking for maximum coverage to unsettle his targets and it worked. Immediately, Debs was recorded as saying police were trying to build up the pressure.

‘All they’re trying to do is, is whoever’s done this photo bullshit, what they’re trying to do is, they’re trying to see if the people are scared.’

Debs had trained his younger partner to believe that police were like armed robbery victims – that if you confronted them they would eventually look away.

Eventually, Roberts decided to take the initiative and rang the taskforce to say: ‘That’s my picture, mate … It looks exactly like me.’ He said that when he saw the picture in the paper he ‘nearly had a fuckin’ heart attack’. When police said they would make some checks and be in touch, he responded: ‘Not a problem, matey.’

Often police try to deduce how a suspect will respond during an interview. In the Debs case it wasn’t necessary. Listening devices picked up his conversation with his adoptive father in a virtual rehearsal of what would happen when he was finally arrested. He would feign that he couldn’t remember.

‘They don’t like it when you talk tough to them … And when you say I dunno, I dunno – that one, they hate it. You know that one? I dunno. I’m not sure … Happened so long ago. I didn’t take much notice.’

Debs knew he was the target of Australia’s biggest investigation yet he still couldn’t resist a little shoplifting on the side.

Shortly before his arrest he ran into Dean Thomas, one of the key Lorimer investigators, in an eastern suburban supermarket. Many times the taskforce had engineered chance meetings, but this one was a genuine accident.

Debs was shoplifting for a dinner party. He had already grabbed some kabana and then stuffed a tray of chicken valued at $15 up his jumper.

Most people would have panicked, or at least headed down another aisle, but Debs headed towards his enemy. He told his wife later that day that he said: ‘How ya goin’ mate? … Have you caught those pricks who … um … killed those cops?’

He thought meeting Thomas in the supermarket meant he lived in the area and this could lead to an opportunity. ‘I’ll have to get rid of him … find out where he lives and kill him.’

But his greatest concern was that because of the chance meeting he had to dump some of his shoplifted goods, including the kabana, although he was still able to steal the chicken.

Debs loved nothing better than a free feed. He once demanded his wife rush home from visiting a sick relative recovering in hospital from a heart attack because he had been offered free Hungry Jacks’ hamburgers at the store where their son worked part-time.

What he didn’t know yet was that where he was going you didn’t need to pay for food. On the other hand, the menu was limited.

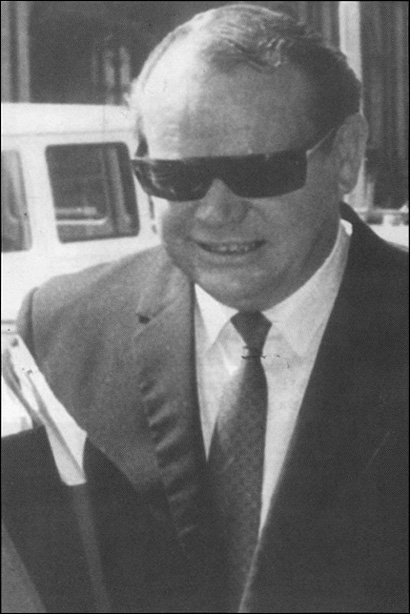

On July 25, 2000, the Special Operations Group moved on Debs and Roberts at 7am and 7.20am respectively. Police were furious when a television news van turned up in Debs’ street before the arrest, although the targets were still taken by surprise.

As he had rehearsed two days earlier, Debs stuck to his story and remained vague on detail.

Sheridan’s plan was to let Roberts go unless the younger man confessed. He hoped a little time without his mentor would break his resolve.

But the more police learned of Roberts the more they realised he was no kid dragged into a situation not of his making. It was Roberts who fired the first shot, hitting Gary Silk, and it was Roberts who, in the weeks before his arrest, was laughing at the police investigation.

In the last weeks before the police raids, Debs started to show signs of concern while Roberts urged his older companion that it was time to start committing more armed robberies.

It was Debs who seemed to worry about how long the investigation could continue and who hoped police would eventually run out of resources, while Roberts referred to committing armed robberies as fun.

‘It’s time for a job, Ben,’ he said, two months before the arrests. It was Debs who counselled caution. ‘I’d love to. But it’s, it’s so hot you wouldn’t believe.’

When police left Roberts in the interview room, his head slumped on the table. Detectives thought this was the first sign of distress and possible remorse. They were wrong. He was trying to sleep. It had been a long day.

When he was finally released, he bragged he would sue the police after his robust, SOG-style arrest and ‘make a fortune’. Even he must have known it was false bravado.

Police let him go to sweat for a few weeks, to give him a chance to consider making a statement against Debs. He chose to remain silent.

But the case did become stronger after the initial arrest raids. While police were never to find the murder weapons – Debs had bragged one had been thrown into a lake and the other destroyed – they found items stolen during the Hamada robberies.

They seized the Hyundai for exhaustive tests. This time, it was taken apart and examined piece by piece. The forensic experts found gunshot residue inside the cabin, the same type gathered on Rod Miller’s jacket, and uncovered a handyman’s attempt to repair damage made by a bullet. It may have been from one of the four shots fired by Miller in the ambush. The dead policeman had actually helped build the forensic case against his killers. Game over.

In the remand jail, Debs received a letter in the prison system internal mail. It was from Russell Street bomber Craig Minogue, who had left a car bomb outside the then police headquarters, killing policewoman Angela Taylor. In the note, Minogue gave Debs some free legal advice. He said not to trust anyone, including lawyers, and not to sign anything. Cop killers, apparently, seem to think they should stick together.

Roberts was finally charged on August 15. Sheridan had considered delaying the final act for a day, to coincide with the second anniversary of the shootings, but felt that would be too contrived. It was, however, two years to the day after Gary Silk and Rod Miller began their last shift on what was supposed to be a routine surveillance operation.

AFTER months of legal argument and delays that seem to have become accepted as part of the criminal justice system, the trial began in Court 12 of the Supreme Court in front of Justice Phil Cummins. Exactly two years after Roberts’ arrest, Jeremy Rapke was finally able to address the jury and outline the Crown case.

The modern-day metal detectors used to search people for weapons before they entered the secure court contrasted starkly with the historic setting of the 19th century law courts.

Unfailingly courteous to jury and witnesses, ‘Fabulous Phil’ Cummins made it clear if he felt a barrister was wasting his time. He seemed to save his most savage remarks for Debs’ barrister, Chris Dane, QC.

It is often said that a court of law is just another venue for theatre and the murder trial was often as much about style as substance. Both sides tried to influence the jury with non-evidentiary tactics.

Dane and his legal team sat on a different table from Roberts’ team, led by Ian Hill, QC, to try to show they should not be seen as a joint ticket.

Debs and Roberts sat in the dock at the back of the court. They did not communicate in front of the jury, again to reinforce the view that they were standing trial as individuals, not as a pair. Debs’ three daughters sat in the row in front of them.

Joanne, the part-time legal adviser, sat in front of her father, her black hair pulled back into a ponytail showing the rings in the pierced tops and lobes of her ears. She was stooped, with rounded shoulders. Next to her was Kylie with brown, highlighted hair, often wearing a blue jacket. Before the jury entered she would sit, smiling and apparently relaxed, considering the gravity of her father’s situation.

Next was Nicole, who sat virtually in front of her boyfriend Roberts, her black hair pulled back and often held with a red ribbon. Her body language changed only when she heard a police tape of her boyfriend and father discussing prostitutes.

The daughters would listen to the evidence, rarely looking around. Outside they could be mistaken for office workers on their way to city buildings, not daily visitors to the Supreme Court to hear their father accused of one of the worst crimes in Australia’s history.

They would sit chatting and laughing less than two metres from the families who were also there every day, the Silks and Millers. Both camps learned to ignore each other like strangers on a train.

To the left of the judge and opposite the jury of nine women and six men were the families of Gary Silk and Rod Miller. Taskforce members sat in front of the families, always well dressed. Court staff nicknamed them the ‘Eddie McGuires’ because they always wore well-cut suits.

The positioning meant that when the jury looked at slides and graphics projected on to the wall of the court opposite them they looked directly over the heads of the Silk and Miller families. This meant the jury was constantly reminded of the loss in human terms.

Debs sat with a foolscap pad filled with handwritten notes. He looked straight ahead and tried to concentrate. It often looked as if it were a battle.

Roberts’ interest ebbed and flowed. He seemed to spend more time looking at people in the court than worrying about the damning testimony.

Both defendants were told by their lawyers to remain silent in court but at one point Roberts could not control his aggression, saying to Justice Cummins: ‘One question: are you prosecuting, or are you the judge?’ Cummins did not respond. He knew he would have the last word. Judges always do.

Even the way the Debs girls sat looked as if they had been coached. It was as if they were waiting to be asked to dance at a debutants’ ball. Only once did their emotions betray them.

They were caught rolling their eyes during one witness’s evidence. Justice Cummins sat quietly during this display, but when the jury was excused he told them, ‘Do that one more time and you’re out for the trial.’ Both defence teams chose to keep their clients out of the witness box. The defences were left with no alternative but to counterpunch, to try to somehow damage the prosecution case without leaving themselves open to rigorous examination. The prosecution called 157 witnesses, the defence just four. Even when they tried to respond, it did not go according to plan.

One of the most damning pieces of evidence against Roberts was a bugged conversation when the younger suspect says ‘I kill Ds’. The Crown alleged Roberts was talking of detectives or plain-clothes police, with the relevance being that Silk and Miller were in plain clothes when they were murdered.

Ian Hill QC, for Roberts, called a speech expert to dispute the police version of the tape. The original questioning of the expert seemed to go well, but then it was prosecutor Jeremy Rapke’s turn. Quietly, he took the expert though his testimony. Again and again he played the tape in front of the jury. Ultimately the men and women who would judge Debs and Roberts heard the chilling words ‘I kill Ds’ 20 times. Each repetition underlined its real meaning. It was a masterstroke by Rapke.

The daughters learnt court procedure and would bow to the judge when they left court. But if the impression was to create an image of a caring family it was shattered when taped conversations were played for the jury. The language, the undertone of dishonesty and violence, and the family’s complicity in the murders made them objects of curiosity and contempt rather than of sympathy.

The trial lasted 113 days and the jury heard evidence for 87 of them. Finally the jury was culled by ballot from 15 to the traditional 12. The extra numbers had originally been included to ensure against a mistrial because of illness. They were sent out to consider their verdict over the Christmas break. Many observers had thought it would be quick and so began to imagine problems as time dragged on but, after seven days, at 10.40 am, they returned to open court. It was the last day of 2002.

Family members and friends of the two dead police cried and clapped as the jury announced that the two men in the dock were guilty of the murders. Debs and Roberts sat impassively. They must have known after hearing the evidence that it was inevitable.

FOR the Silk family, the four-month trial was the end of an exhausting journey that began when Gary was shot on August 16, 1998. Gary’s mother, Val, went to the Supreme Court nearly every day, even though she sometimes ended in tears.

She heard the D24 tape recorded when her son’s body was being discovered. She heard the strained voices of the police as they searched for the gunmen. Then she heard the bugged conversations of the suspects as they calmly talked about how they murdered the two police and were prepared to kill more. But she had been briefed by the police taskforce on what to expect, so there were no surprises. But while it was no longer a shock for her it would always be shocking. Behind her, on the court wall, they projected a picture of her son, lying dead in the grass next to Cochranes Road with a bullet in his head.

During the weeks and months of mundane evidence there were moments that will stay with Mrs Silk for life. Such as when they played one of the incriminating tapes catching the two killers talking about what they had done.

Mrs Silk says Roberts used his left hand to conceal his face from the jury, not because he wanted to hide any expression of guilt from the people who would ultimately judge him, but because he was trying not to laugh. ‘His face was red with the effort. He was nearly hysterical.’

Despite the trauma, she went every day. ‘I’m here as a mother. It is the last thing as a mother I can do for my son. I want the jury to see that he had a family.’

Ian and Peter, her two surviving sons, sat with her. Peter took the time to be there and Ian worked through lunches and nights to keep up with his job as the chief executive of one of Australia’s biggest superannuation funds.

But Gary’s father, Morrie, who so desperately wanted to see his son’s killers caught and convicted, couldn’t. He died from cancer on December 28, 1999, seven months before Debs was arrested.

‘They killed two members of my family that night. Morrie was diagnosed with lymphoma six months after Gary was shot. The doctors said it was the stress that brought it on,’ Val Silk was to say.

In court, she always wore a small pin on her lapel. On its face was the logo of the Special Operations Group, the police who arrested Debs and Roberts. It was at a wake for her son that a friend of Gary’s, an SOG member, gave her the pin. ‘I was given it to wear on special occasions, I wear it every August 16 (the anniversary of her son’s murder) and at court.’

In the sunroom of her neat suburban house there are photographs of the type seen in most family homes. On the television set is a picture of Gary in his police uniform. On the table are pictures of the three Silk boys, smiling at Ian’s wedding.

On the wall is a group photo of nearly 100 people standing on the steps of the Esplanade Hotel in St Kilda – all wearing a special dark tie with the initials GMS – Gary Michael Silk. It was his wake and Val and Morrie are there, wearing the tie like all the others.

On the first day of the trial, Ian and Peter and a group of Gary’s closest police friends wore their ties. It was a small statement of solidarity

For the last few months of the trial, Mrs Silk was desperate for the jury to return their verdict. ‘I want my two remaining boys to get on with their lives. And I want the taskforce team who worked on the case to be able to get on with theirs, too.’

She knew of one investigator who asked his wife to have a caesarean birth so he could be back at work the next day. ‘They have worked so hard for so long.’

Mrs Silk wanted her son’s killers caught but she was always concerned that the investigators who worked thousands of hours trying to find them may have been damaged in the effort. She would ring Paul Sheridan, to make sure he had given his team days such as Christmas off and that they were not becoming burned out. ‘She was a bit like a mother to us all,’ Sheridan says affectionately.

She always knew Gary would be a policeman. Even in high school, he wrote that one day he would join the force. A senior officer, a friend of the family, sat down and told him all the drawbacks of policing. When it was clear Gary would not change his mind, the officer told him that if he insisted on joining he would make friends that would last a lifetime. He was not to know how short that lifetime would be.

He joined at the age of 21 and, although quiet by nature, became one of the most popular members stationed at St Kilda. Everyone had a story about Silky.

But he was more than just a man in a blue uniform. His mother says: ‘Gary had another life. He was very close to his family. He adored his nieces and nephews. When we came home from holidays there would be flowers at home to welcome us back.’

The jury’s verdict was a message to all criminals, she says. ‘If you kill police you will get caught.’

CARMEL MILLER spent all day writing thankyou notes to the 90 friends and relatives who had sent cards welcoming the birth of their first child.

But she didn’t seal the envelopes – she wanted her husband, Rod, to sign them before they could be posted.

Even though he was tired from a Friday afternoon shift, Rod Miller sat up to finish the letters. It was no chore; they had tried so hard to have a baby that the birth of James, just seven weeks earlier, still seemed like a minor miracle.

The letters were posted the next day before Rod returned to work for a night of watching eastern suburban restaurants.

By the time the letters arrived on Monday, Miller was already dead. Shot by strangers in a nondescript street in Moorabbin.

On the night of the murders Carmel stayed with her brother, Brendan, as they planned to go to the airport in the morning to farewell their sister, Michelle, who was flying to Hong Kong. At 2am, police knocked on the door. They told Carmel her husband had been shot but the initial reports were that he was not badly injured.

On the way to hospital she tried to remain positive. ‘I was on maternity leave and I thought if he had to be shot it was the best time, because I would be there to look after him.’

She asked a policeman at the hospital, ‘Why was he alone? Where was his sergeant? What happened to Gary?’

The policeman answered, ‘Don’t you know? Gary’s dead.’

Even then she couldn’t comprehend that her husband was losing his fight for survival. ‘He was always larger than life. I could never imagine him being badly hurt.’

Then a surgeon told her that his major organs were ruptured by the gunman’s bullet and they were desperately battling to save his life.

‘I had a seven-week-old baby, I told him to go back and save him. Twenty minutes later he came out … I knew Rod was gone.’

Rod Miller had just left the army when he met Carmel at a wedding in Melbourne in 1989. She refused his first invitation for a date but he persisted and she later weakened.

They went out only twice before he flew overseas on a backpacker’s holiday. He wanted a break before joining the police force. They wrote regularly and when he returned they became an item.

He joined the police force and graduated in August, 1991. They married three years later.

Carmel Miller just happened to fall in love with a man who wanted to be a policeman.

‘He loved his work but he was able to leave it at the door when he came home. We would go to art galleries; he was interested in pottery and classical music. Most of his mates didn’t see that side of him.’

An empty bedroom and shattered dreams … decades later, the disappearance of Eloise Worledge still haunts.

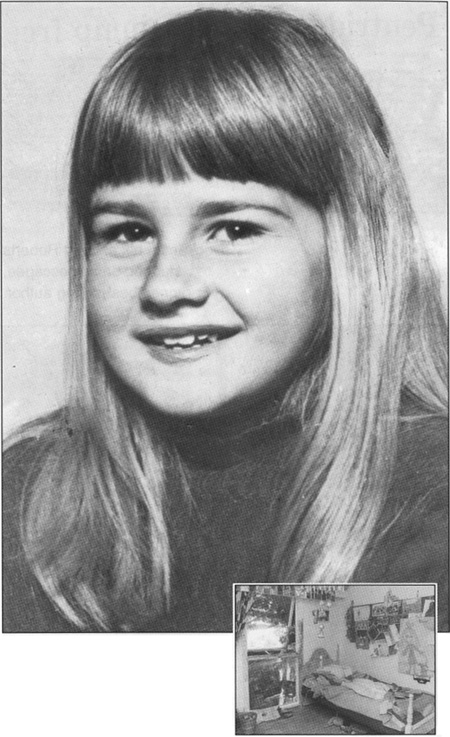

‘Doc’ Smith a.k.a. Greg Roberts … student, bandit, escapee, gun-runner, best-selling author.

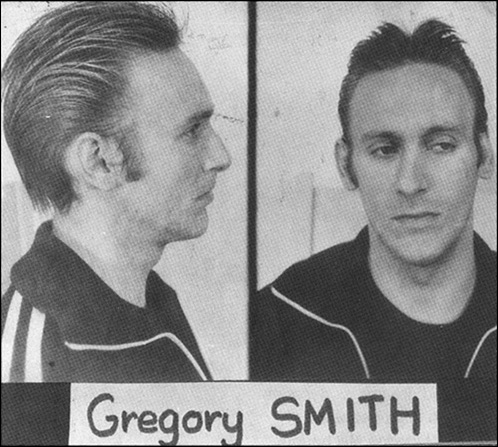

Fake gun, fake silence … but the robberies were real.

From safe house to Big House … ‘Doc’ Smith was arrested at this Macedon holiday house.

Rogue barrister Robert ‘Rolls Royce’ Vernon … the closest he got to silk was women’s underwear.

Drug squad target Darren Jackson … shot by police surveillance camera. Later, almost shot by the SOG.

Drug dealer Dan Mosut thought he had a drug safe-house. He was wrong.

Estate agent turned drugs dealer Peter Reid … from bricks and mortar to bread and water.

Prolific armed robber Aubrey Maurice Broughill. His death is a mystery. Turtles (inset) unable to help with police inquiries.

Carmel had her own career as a talented interior designer. Together they had meticulously renovated a bayside house.

She talks about her life with Rod with love and warmth and refuses to let the injustice of his loss poison her memories.

‘I look at the life I had with Roddy and I don’t have any regrets, There are no “if onlys”.

‘It doesn’t mean I accept what happened. There is not a day that goes by when I don’t think of him.’

Just days before his death they sat together in their home and talked of how life seemed so perfect. They had the careers they loved, a healthy, happy baby and the home they had built. She asked him if he thought the bubble would ever burst. He responded by telling her not to be negative and enjoy the moment. Two weeks later he was dead.

Rod had been back at work only a week after taking six weeks leave. On the day he was due to start stakeout duty, Carmel bought him a Timberland jacket as an impromptu present. He was wearing the jacket when he was shot the next night.

In that jacket police found slivers of glass and gunshot residue that were eventually traced back to the Hyundai and the two killers.

She buried him, not in his police uniform, but in the casual clothes he loved, including his favourite Mambo shirt and odd socks.

For the first week she couldn’t sleep and for the first year she was consumed with grief. But even at her lowest she always believed her husband’s killers would be caught. ‘There has never been any doubts in my mind. Paul (Sheridan) made me believe. He told me it’s going to be a long road and there would be frustrating periods, but we would get there.’

Her absolute faith in the taskforce was tested when on February 11, 2000, detectives monitored Debs contemplating murdering her and James.

It was three days later, on Valentine’s Day, when Sheridan rang her and asked ‘Where does Jimmy go to kinder?’ The experienced policeman thought his level voice would not betray his concern but Carmel knew immediately that something was wrong.

‘I asked, “Are we safe?” ’

He then told her that some threats had been picked up on listening devices. ‘My heart started to race and I asked him, “Will we be fine?” He said, “Absolutely.” I then knew nothing would happen.’

A year after the murders Carmel returned to work. ‘I buried myself in trying to be the best mother I could and in my work’. But she was still numb.

Two days after the first suspect, Bandali Debs, was arrested on July 25, 2000, she went for her usual short walk from work to buy lunch. She noticed a pleasant garden and later told her colleagues of her find. ‘They told me it had been there for years. I just hadn’t been able to see it. That day was the first time I had been able to see beauty since Rod died.’

With the arrest came more publicity. She had tried to shield James from the details of how the father he would never know had been murdered.

While she could protect him from radio, television and newspapers she could not stop talk at the kindergarten. She was pulling into their driveway when James suddenly asked, ‘Did someone kill my Dad?’

He was three years old.

Carmel Miller spent nearly every day of the trial within metres of her husband’s killers. She would sit and listen as tapes were played of these men, talking of the murders, sometimes gloating, always plotting.

She sat in court, arm’s length from Debs’ three daughters, and heard their recorded conversations as they planned moves to thwart the police investigation.

‘I feel nothing for them. I have never let them inside my thoughts. To me they are just nameless, faceless people. I don’t want to feel any emotion.

‘What sort of men would do this? I can’t comprehend them and I don’t want to know about them.’

She went to the trial because she wanted to support her husband’s memory and the taskforce. ‘But I also went because I wanted to know what happened and I wanted the jury to know he had a wife and son.’

After the trial, Carmel moved from the house she rebuilt with Rod. She put James in a new school and began to start again.

‘We just want to be normal. I have been consumed with this for four and a half years. Someone told me of a saying, “I didn’t choose to be a victim but I sure as hell won’t remain one”.’