Cities are focal points for inequality in the past. The ranked differences among their inhabitants – in terms of the work they do, the resources they can acquire and the sheer scale at which all these are carried out – is what fundamentally separates cities from the Neolithic world of villages and towns. Cities are also associated, if we paint the past in very broad brush strokes, with the intensification of new technologies. Cities are usually associated with the dawn of the metal ages in Europe, Western Asia and Africa,1 a complicated interplay of resource extraction and craft specialisation. One of the earliest exploitations of metal seems to have kicked off in the mountains of what is now Serbia among the dense villages of the Vinča culture 7,000 years ago; however, it’s not until the dawn of the urban age some 2,000 years later that metals become the lifeblood of the world’s first arterial trade networks. What was a symbolic and functional invention becomes, in the presence of so many people and so much hierarchy, a commodity. I have seen with my own eyes the delicate Anatolian animals, cast in unyielding bronze, cached in the tombs of the people who straddled the trade routes of the early Mesopotamian cities.2 Of course, one of the other forms of metal from that very same site is a spearhead, and when we look at metal as it circulates through these early empires, it’s as much as a weapon as a decorative art. Weapons are older than metal, and violence is older than cities, but these next few chapters take a closer look at the possibility that cities, with all their weapons and all their people, have intensified one of our oldest traits: violence.

What can we say about violence in the past? And what’s more, does anything really need to be said? Anyone who catches the news will be fully aware that our species is doing its level best to live up to Hobbes’ description of ‘nasty and brutish’. We are a violent species in a violent clade, and the evidence for this can be extracted from the skeletal remains we have left in our bloody wake. Readers who have ever encountered, interacted with or been small children will no doubt be intimately acquainted with our seemingly inherent hair-pulling, pushing, biting and scratching nature. However, what do we really know about our violent tendencies? Are we evolutionarily engineered towards it, with only a thin veneer of civilisation preventing us from going full Lord of the Flies? Or is it civilisation itself, with its vainglorious wars of conquest, its capital punishments and its relentless competition, which moves the hand that holds the sword?

This is a rather big question, and will actually occupy the next three chapters. To try to get a handle on things, I’ve broken the discussion into three categories: interpersonal violence, structural violence and community-scale violence – the latter better known to poets and pedants as war. This chapter will introduce the techniques that allow us to reconstruct evidence of violence from the skeletons of the past. These techniques – forensic, archaeological and bioarchaeological – are the same ones we use to identify structural violence and warfare in the archaeological record. This chapter, however, will set the stage for understanding the origins and patterns of conflict through evidence of violence at its most basic level: one-on-one, me against you.

The antiquity of people smacking each other upside the head must be presumed to go far, far beyond the invention of urban life, so why do we need to think about it here? Much like the impacts of disease, which have always been with our species, urban life acts as a sort of hothouse for the social, economic, cultural and psychological factors behind interpersonal violence: human competition, for status, for access to resources or even for sport.3 We know that violence did not begin in cities. Life on earth is violent, whether you’re a cognitive marvel of primate evolution or an unsuspecting, happy-go-lucky spider that just happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. Life for our little clade of humans and their ancestors has been very violent indeed, and we have the bones to prove it. For example, we have an approximately 430,000-year-old skull from Spain that seems to be pretty unambiguous proof that we were bad before we were even us. The north of Spain is a karstic region that is absolutely littered with caves. Buried deep within are the last traces of some of our long, long lost relatives, and at a site in the Atapuerca Mountains near modern-day Burgos, archaeologists uncovered an even larger surprise.

The site of Sima de los Huesos translates as ‘the pit of bones’, which is a very apt description. The bones in question are from hominid ‘ancestors’ dating back almost half a million years, and they have yielded fascinating insights into the world our ancestors inhabited. Around 28 human(ish) individuals were found in the pit, alongside more cave bears than you could shake a stick at. Cranium 17, one of the skulls found at Sima, has holes in it. This is less surprising than you might think – after having probably fallen into their position from elsewhere, hundreds of thousands of years in a cave largely occupied by giant extinct bears might be imagined to have had knock-on effects on any bones underfoot. However, a recent publication from the Sima de los Huesos research team suggests that the holes in the adult male skull are more than just accidental damage. They argue that the two holes in the skull are clearly evidence of repeated blows with the same weapon: signs of lethal intent. The blows seem to have occurred around the time of death, which for the authors of the paper makes Cranium 17 the first known man to be murdered in all of human history.4 Many of the other bodies found with Cranium 17 also show signs of injury, so perhaps he wasn’t alone in his violent death. While this has been heralded as the very first sign of interpersonal violence seen in our entire human history, physical anthropologist Tim White has made a case for cannibalism, if not murder, in one of our early ancestors, an early member of the genus Homo found with stone-tool cut marks in the South African site of Sterkfontein dating back 1.5 to 1.8 million years ago. However, as discussed further below, the difficulty in identifying these ‘firsts’ from the archaeological record is that it can get very difficult to tell a killing blow from a bit of damage to the recently deceased.

I first became enamoured of the study of the human past on a long-ago course in physical anthropology, taken on a whim at a local community college in Southern California.5 After that, I was hooked; I changed my major to archaeology and went off to UCLA to learn more. At various points in my undergraduate studies, the subject turned to the Chumash, a widely spread indigenous group that had occupied a stretch of coastal California from Los Angeles up past San Luis Obispo. Theirs was a fabulously rich and complex culture encompassing the manufacture of prestige tradeable shell beads (essentially, money) and a (small ‘b’) byzantine network of social alliances that would put the Borgias to shame,6 before the Chumash people were eventually decimated and enslaved by Spanish missionaries. Despite the brutal nature of repression imposed by the Spanish and the Church, the Chumash culture survived the Mission period, and they take an active role in researching and sharing their long and fascinating history. The physical anthropologist Philip Walker had an excellent relationship with the Chumash individuals responsible for their cultural heritage, and devoted much of his impressive career to studying the remains of their ancestors.

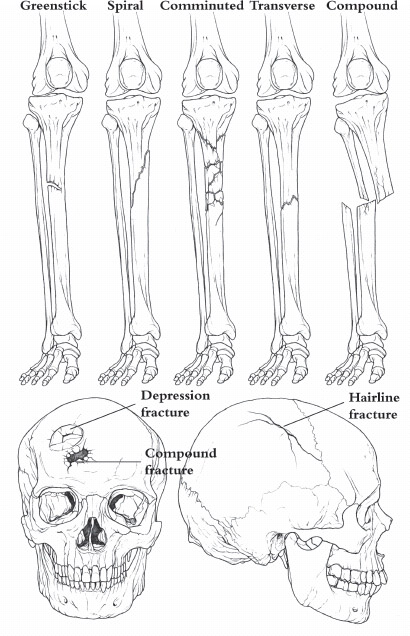

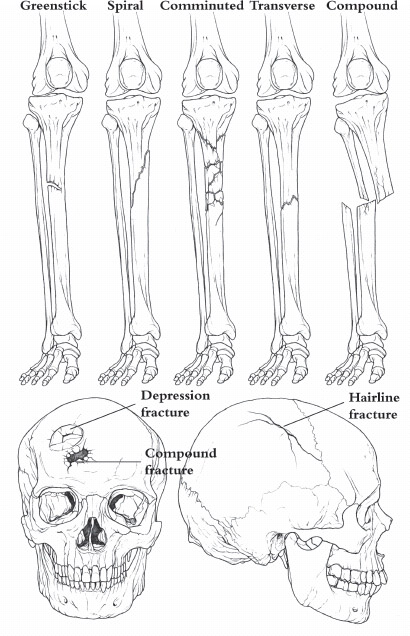

Figure 4 Illustration of basic fracture types as applicable to long bones and the skull.

One of the most interesting things his research uncovered was that several Chumash skulls possessed a notable lumpiness. This was not some sort of genetic deformity, but rather a series of welts right on the skulls themselves. Walker discovered that the Chumash skulls showed high numbers of depressed cranial fractures – skeletal evidence of trauma to the skull that had been sustained during life. The lumpiness arose from where fractures to the bones of the cranial vault (the dome of the head, more or less) had healed over unevenly. Of course, there are many ways to smack your skull; in the modern world, low-lying lintels and unexpected lighting fixtures are the blight of the human with the audacity to be of over-average height. However, the impressions in the Chumash skulls were regularly circular, or at least approaching circular. This begins to suggest that the prehistoric Californians were less clumsy than confrontational.

The Chumash were a large group, with marked internal hierarchies; this must have thrown up sufficient occasions for inter-group tensions to reach boiling point. Aside from reading the story of a Chumash girl abandoned for years in the California Channel Islands around the time of Spanish incursion,7 I knew very little about Chumash culture, and was reasonably delighted to follow Walker’s suggestion that they had perhaps taken up a rather unique method of conflict avoidance known from other Californian cultures. Further north, another group of coastal Native Americans from the Monterrey area of California went to the trouble of establishing a very ritualised form of grievance procedure, witnessed by a somewhat judgemental military attaché of the colonising Spanish forces, one Pedro Fages:

If two of the natives quarrel with each other, they stand body to body, giving each other blows as best they can, using what might be called spatulas of bone, which they always carry for the purpose of scraping off their perspiration while in the bath and during the fatigue of their marches. But as soon as blood is drawn from either of the combatants, however little he may shed, the quarrel is forthwith stopped, and they become reconciled as friends even when re-dress of the greatest injury is sought.

Archaeologists have indeed found evidence of ‘spatula-like’ bone tools, interpreted as being similar to Roman strigils and used to keep the body clean by scraping off sweat. Bioarchaeological analysis of the skulls uncovered in excavations of Chumash remains can identify signs of blunt force cranial trauma either visually, spotting literal dents in the cranium, or through radiography, using X-rays or CT scans to spot areas of dense bone that are the hallmarks of healed trauma. These are exactly the lesions you might expect from the sort of spatula-spat Fages had described. The case that captured my attention, all those years ago, was that the skull of one elderly Chumash woman showed evidence of nine separate healed lesions; one would like to imagine this a testament to her ability to argue a point, or at the very least, her tenacity in doing so.

Of course, it’s not guaranteed that the lumps and bumps of the Chumash skulls were caused by anything so orderly as ritual conflict settlement. Forensics and modern hospital records demonstrate the harrowing statistics behind blows to the head in the modern day; road accidents in particular are the leading cause of traumatic injuries, distantly followed by falls and assaults.8 A recent study in India estimated that about 60 per cent of traumatic brain injuries were due to the modern invention of the car accident, with a further 20 per cent explained by falls and around 10 per cent explained by violence. These numbers vary considerably around the world and among different social groups within even the same countries; a report calculating statistics for the latter half of the twentieth century found that the incidence of head injuries from violence was 40 per cent for inner city Chicago and 4 per cent for a more bucolic suburb, with higher rates in men than in women. These are of course clinical reports, which must be considered in a different light to the evidence we can see on skeletons – we have no living witnesses to report that someone has fallen on their head, and no soft tissue lacerations to testify to injury.

Much of what we know about injury comes from modern medical studies, conducted on populations in the developed world who have access to hospitals of the sort that are stalked by epidemiologists. This works very well, up to a point – for example those road accidents, which are unlikely to account for the majority of archaeological cases. Both clinical study and forensic investigation contribute to what we know about broken bones and skull dents found on human remains from the distant past. Through clinical studies looking at population-wide trends, we know that certain types of fractures are more likely to be caused by specific activities, falls or impacts. For instance, a small study looking at the number of under-18s at a trauma clinic in New Jersey found that about 43 per cent of fractures treated were caused by interpersonal violence, a much higher rate than that commonly reported for a general population. Most of these occurred in teenage boys,9 with the most common fractures being of the nose and the jaw. Cuts, scrapes, impact craters and perforations in bone can be traced to specific implements. Moreover, the prolific violence that our species is known for means that there is a wealth of forensic studies that can place the number, angle, depth and position of damage to the skeleton in context, telling us everything from the emotional state to the handedness of the attacker.

Here the work of Phil Walker again comes to the forefront. In a relatively ground-breaking review in 2001 (the same year I was driving to Malibu at 5.00 a.m.10 every morning to complete my undergraduate fieldwork on a Chumash shell mound11 site at Point Mugu State Park campground), he laid out a bioarchaeological theory for understanding the lumps and bumps on the Chumash skulls he had observed, and more besides. While the only type of violence we can interpret from the past, he admits, is limited to the physical violence that leaves scars on the bones themselves, there are basic principles that can allow us to reconstruct a blow-by-blow account of violent injury and death in the past from the skeleton. Specific types of fractures signal particular likely factors, and they can largely be categorised into how the bone broke and where it broke. Taking the latter first, fracture location is one of the main clues to the activity that caused the break, and these are usually grouped into cranial (head) or postcranial (the rest) in large epidemiological studies. Cranial fractures can either include the bones of the skull vault (the cranium, the bits without a face on) or the face itself, and they are one of the most common sites for fractures, now or in the past. Facial fractures by far and away most commonly occur in the nasal bones; then as now, a broken nose is likely to suggest some sort of contretemps.

The depressed cranial fractures that Walker observed on the Chumash are one of the most studied pathologies in bioarchaeology. Walking through the process of formation allows us to see how knocks to the head that the victim survived for some time can be differentiated easily from fatal blows. Anyone who has ever broken a bone and had it knit back together will be familiar with the idea that, if treated properly, a broken bone will heal. This can be contrasted with teeth, as discussed in Chapter 2, which, when chipped or broken, stay that way.12 Bone constantly remodels throughout life, with specialist cells eating away at the insides while other specialist cells lay new bone down on the opposite side. This process is ongoing while an organism is alive; there isn’t a bone in the adult human body that is really ‘older’ than about 11 years, because the remodelling process constantly replaces bone over time.

A smack on the head with sufficient force causes a cascade of reactions. This is blunt force trauma – a word bandied about by television hospital soap operas and hack novelists alike, so you can be sure it’s a fairly simple concept. Blunt force trauma is the wound you get when you’re hit (hard) by a non-pointy, non-projectile weapon. Colonel Mustard in the library with the candlestick – this is how we end up with skulls with depressed cranial fractures. The bone itself might be smashed in, either right the way through or, in less percussive cases, only denting the skull. The periosteum, the sensitive membrane around a bone that produces all the cells for building up or taking away more bone (and which I have in the past asked my students to imagine as a sort of sausage casing around the bone), signals for a host of resources to be trucked into the affected area, forming a bruise13 that pools the material for repair. The broken bone tries to knit itself together with new bone, first forming a loose bolus of cartilage around the fracture site, before replacing this soft callus with woven-looking bone – a process that takes several months. If the bone is more or less in the right place, the callous is gradually resorbed until the bone looks pretty much the way it did before the break. If the bone has been dramatically shifted out of place, healing can result in dramatic lumps, the callus constantly laying down in exotic new directions as it tries to reach the disparate ends of the bone. In extremity, entire false joints can be created if the broken bone keeps being pressed into service before the fracture ends can mesh back together. If the break extends through the skin (a ‘comminuted’ fracture), you add the excitement of infection and septicaemia to the mix. With cranial trauma, if the blow hasn’t killed you, nor the build-up of pressure from all that extra repair material rushing to the site of the wound, the skull will heal over; but, as with many DIY repair jobs, the rebuilt area may not be quite on level with the rest of the structure.

The healing process is one of the ways that physical anthropologists can identify fractures, but if the healing processes all went swimmingly we wouldn’t have any evidence at all. Luckily (for science), the techniques to reset fractures and immobilise limbs that we use today were not necessarily always employed in the past. It should be remembered, however, that the evidence of injuries to bone can disappear with time; what we see in the skeletons of the past is evidence of either poorly healed injuries or injuries that were still healing at the time of death. The mechanism of healing fractures allows us to establish a timeline for wounds we see in bones. A small, very dense lump around a bone with a discontinuity visible in X-ray might suggest a nearly healed fracture of several years’ antiquity; a hole in a skull with tiny microscopic evidence of a few bone cells stirring around the very margins would suggest that healing was an abortive process interrupted within a matter of hours or days by death. The former is easily identified as an antemortem injury (occurring before death), while the latter might be considered a perimortem injury (occurring around the time of death). By contrast, a great whacking hole the size and shape of a mattock end found in a skull on an archaeological site in close proximity to a nervous and/or sheepish-looking archaeologist is likely to be a very postmortem injury, the result of ‘taphonomy’ – a fun Greek way of describing the things that the environment14 does to the body after death. Forensic archaeology makes great use of taphonomy to determine timelines for body decomposition, insect invasion and burial practices like ritual postmortem dismemberment. The ‘body farm’ run by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill is perhaps the best known of these experiments, though considerable research is done in unexpected locations throughout the world.15

Skulls are also rather uniquely suited to puncturing wounds. It’s for the same reason that depressed cranial fractures are so common: skulls contain a great deal of surface area and sufficiently integral parts that they are frequent targets for attack. While the medical literature attributes most depressed cranial fractures16 to blunt force trauma, evidence of sharp force trauma – which is very much what it sounds like – is also commonly observed on the skull. Sharp force is differentiated from blunt force mostly by the area of bone impacted, and in a forensic context usually implies wounds made by weapons. Chopping, cutting (‘incising’), slashing and stabbing are the main modes of inflicting sharp force trauma, and, as any half-decent prison show will demonstrate, anything can be a weapon.17 Differentiating between the two types of trauma may occasionally be difficult. An axe may well stave in quite a bit of skull, but is technically an edged weapon; blunt force with enough force can push through just as much cranial bone as an axe. Forensic anthropologists and bioarchaeologists must use whatever clues remain to piece together the method of fracture. Where thin little breakage lines snake across the surface of the bone, like fissures in dried mud, it’s possible to trace these lines back to their source to try to gauge the original direction and impact of the blow. Of course, it’s far easier to reconstruct the causes of fracture if you can simply match the edge of the weapon used to the dent made in the skull, and even better if the weapon is still wedged in.

Getting back to the rest of the body, postcranial fractures can also be caused by accidents or either blunt or sharp force trauma, blunt force being more likely to cause a fracture. These fractures are broken down into their constituent bones or functional limbs. There are too many potential fractures to go into for practicality,18 but there are a few basic types that come up again and again in forensic and medical literature. Wrists and forearms are pretty key sites for damage. Another fracture that affects the forearm, and a common one in modern medical practice, is Colles’ fracture, which affects the part of the radius that meets up with your wrist – if you put your hand down flat on a table, fingers pointing away, you can feel the lumpy end of the radius on the thumb side of the hand. Like most wrist fractures, Colles’ occurs when you fling your hand out to break a fall, and isn’t necessarily diagnostic of violence. The wrist ends of both radius and ulna are frequent sites for this kind of fracture.

As an experiment, stand with your hands at your sides. Imagine that you are having a perfectly nice time standing around and minding your own business, when suddenly – an attack! Something is coming at you from in front and a bit above; perhaps it’s a candlestick, perhaps it’s a rain of frogs. Either way, if you instinctively brought up an arm to ward off the airborne amphibious menace, then you would understand the underlying mechanism of the ‘parry’ fracture. The parry fracture takes its name from the action of parrying off a blow or attack,19 and affects the ulna, one of the two bones that make up your forearm. The ulna is the bone that forms the knobbly bit of your elbow; if your hands are flat down at your sides, it’s the one in the back (the other is the radius). If you have one hand in the air, with the palm down, and someone is coming at you with a weapon, it’s the ulna that gets it and, if the frog has sufficient velocity, the ulna that breaks.

Parry fractures are one of the most frequently cited archaeological indicators of violence. In his summary of evidence for forearm fractures relating to violence in the past, eminent physical anthropologist Clark Spencer Larsen notes that parry fractures are more likely to be related to interpersonal violence when they disproportionately affect one side of the body in a population. The over-representation of left forearm fractures might indicate that a right-handed person was defending against attack, or conversely an armed right hander might have their weapon in their dominant hand, leaving the left to bear the brunt of an opponent's strikes. Larsen notes injuries following this pattern from cultures as varied as groups of Australian Aborigines to native Hawaiians, but this is not a very representative sample of all the various cultures that have ever fought among themselves (or others) with weapons liable to break arms. As with all bioarchaeological evidence, more support is needed to clearly identify signs of violence. One potential additional indication of whether a fractured forearm is a clue to violence or to clumsiness is in the people it affects. If adult males make up most of the affected, then you might speculate that the injuries sustained relate to a social role they play. If one of those social roles involves clubs, shields or the aggressive deployment of both against other human beings who also have clubs and shields, you might well expect a higher number of parry fractures in adult males to be the bony evidence needed to reconstruct how those men lived. Similarly, if fractures are equally distributed among men and women, and it’s clear that otherwise they occupy quite different social roles, the interpretation of fractures found might lean towards accidental injury.20

The rest of the postcranial fractures build up similar lines of evidence. Ribs can be fractured accidentally or violently; even coughing too hard can be enough to crack one. Sometimes it’s the type of fracture, rather than the location, that gives away the violent origins. A majority of radiologists consider metaphyseal fractures, where the still-growing (and therefore less firmly attached) end-plates of children’s bones are literally shaken loose, to be a damning indictment of child abuse. Stress fractures can result from habitual activities taken a step too far,21 and commonly occur on the feet and lower legs of athletes, military cadets and keen Jazzercisers.

Fractures sustained at different times of life can have subtly different effects on the skeleton. The best known of these is the ‘greenstick’ fracture that occurs in kids, so called because the high plasticity of the juvenile skeleton leads to long bones shearing in a rotating direction; just imagine your six-year-old forearm being twisted and broken like a twig off a tree. My personal experience of fracture is just such an occasion. Having inherited a pair of roller skates of unquestionable style and coolness,22 I was determined to skate everywhere. This included piles of loose dirt, which meant that I promptly went tumbling and landed heavily on the arm I threw out to catch myself. I managed to fracture something in my elbow, but my bones were still growing and nothing was knocked firmly out of place; the sausage casing of the periosteum was presumably intact, so my growing bones could knit together in more or less the right shape. If I’d repeated this exercise later in life, say with a borrowed bicycle and the steep hill on the north side of Finsbury Park in London, I probably would’ve managed a Colles’ fracture.

Of course, as with almost all categories of skeletal evidence, we require multiple strands to make the case for violence. As bioarchaeologist Margaret Judd has pointed out, a stress fracture to the ulna caused by repetitive actions (like certain sports) can be indistinguishable from an authentic parry fracture. However, it’s possible to overcome the inconclusive nature of the vast majority of archaeological evidence of violence.23 A prime example is the co-occurrence of parry fractures with evidence of injuries to the head, which signals that there were blows being aimed in that direction and actively warded off. However, our recurring problem in the study of fracture patterns is the unfortunate lack of fractures identified.24 Without all of these compounding lines of evidence, the life of the bioarchaeologist is rendered difficult indeed.

Not all fractures are the result of violence, of course. Hip fractures, for instance, are one of the most common injuries sustained by older females, but no one is particularly concerned that this is the result of a sustained campaign of violence against little old ladies. Hip fractures just happen to be one of the many painful consequences of osteoporosis, and it’s older women who are most likely to have osteoporosis. It’s also worth reiterating that a well-healed fracture, like my elbow, might completely resorb into a perfectly normal-looking bone with time. Even the telltale differences in bone density visible on an X-ray or CT scan might resolve themselves, leaving no one any the wiser.

So, we must move beyond the evidence of fractures. They are not the only clue we can find to violence in the past, and we can see further evidence of violence from sharp force trauma. The sharp edges of weapons (or tools, or ice picks) can scrape tissue and even bone on their way across or through the human body. There are a few basic forensic principles that allow us to reconstruct some of these injuries, though it should be remembered that we know a lot less than we could about how these injuries form because it’s considered bad form to go around stabbing people in slightly varied ways just to see what their bones look like afterwards.25 On that same count, however, we know rather more than we would like, because there are a great number of people in this world who don’t have the kind of moral constraints a university ethics board imposes, and the bodies they leave behind form the backbone of our understanding of traces of sharp force trauma. The basic concepts are actually very simple: weapons with a cutting edge meet bone and interact in a few circumscribed ways, because physics. A slashing attack that reaches bones will be more likely to leave a long, but not deep, cut mark on the affected bones. A stab, by contrast, might leave a very deep mark, or an inconsequential nick; most stabs are aimed (if they are aimed at all) at the soft, vital bits of the human body. An axe – well, it’s fairly obvious what axes do. The more force behind an injury, the more difficult it is to tell what caused it, because there is likely to be much more damage to the bone, obscuring any initial punctures, scrapes or scratches on entry.

Even when it comes to dealing out death and violence, there is a ‘correct tool’ for every job. This is an adage that hangs on the human propensity for laziness just as much as it does our propensity for invention. The idea of using whatever is to hand, culturally or practically, applies to the act of violence just as it applies to mowing the lawn. Specific weapons leave their own specific wounds in the skeletons of the dead, and just as tool cultures might vary from group to group, the weapons of choice can also follow cultural lines. The earliest argued case of a proper weapon causing injury comes from the cave site of Skhul, in modern-day Israel, somewhere between 80,000 and 100,000 years ago. A spear was used to stab an anatomically modern human male, Skhul 9, in the left leg once or twice before sinking all the way into the pelvic cavity. The blow would have been fatal, and as archaeologist David Frayer has described in the separate case of a Mesolithic man with telltale stab marks on his vertebrae, unlikely to have been caused by having pretty much the worst Buster Keaton moment ever next to a pile of spears. However, what looks like murder to some looks like postmortem damage to others: physical anthropologist Erik Trinkaus espoused the position that the damage was caused after death, meaning that we aren’t looking at a cold case from a time when we could pin it on the Neanderthal neighbours.

Phil Walker made particular note of these cultural leanings in his survey of violence: the British, for instance, sustain (and deal) a disproportionate number of the pint-glass-based injuries in the world.26 In a similar vein, living in North America dramatically ups the odds of encountering a baseball bat in an unsporting way. In much the same way, the injuries weapons meted out in the past can vary from group to group and region to region. Occasionally, even the evidence of medical invention is a clue to medical necessity. Take for example the Inca, who ruled their empire with clubs and … cranial surgery. The extraordinarily high number of skulls found with holes deliberately drilled into them while the owners were still alive has been at varying times interpreted as ritual or spiritual, but a study of several hundred skulls found that many of these surgical interventions were associated with cranial trauma. The use of clubs as the primary weapon in Inca warfare and the subsequent blunt force trauma they could cause may account for this remarkable trend. The antiquity of this traditional form of battle may also explain how Inca surgeons had gotten so good at drilling holes in heads by the 1400s that they achieved nearly 90 per cent survival rates.27

Sometimes the evidence of violent damage to the skeleton is more oblique and requires a circuitous logic to be recognised as such. Sometimes, it’s just easy. Bones are not the only part of the human body that can be damaged. On occasion, the soft tissue of archaeological human remains is preserved sufficiently that we can identify marks of violence almost in the same way that a forensic investigator might address a recent homicide. Organic preservation is subject to all sorts of caveats. Some humidity is bad, but total immersion in peat is great; a bit of heat will speed up deterioration, but a lot of dry heat will lead to mummification. There are environments all over the planet that either speed up the destruction of soft tissue or miraculously preserve it: arid deserts, frozen tundra or even anaerobic peat bogs. While desert-dwelling mummies might be better known, it’s actually in the very cold parts of the world that we see some of the most surprising finds preserved, up to and including a little 40,000-year-old baby mammoth from the hard permafrost of Siberia.28

Bodies do not appear out of deep freeze very often, but when they do, the results can be spectacularly surprising, a sign that the stories told by skeletons are perhaps far more circumspect than reality. The very particular case of Ötzi the Iceman is exactly such an occasion, and gives us reason to doubt our ability to ‘find’ violence in the archaeological record as easily as we sometimes seem to think we can. Ötzi is the name given to a man who died in the Italian Alps sometime around 3350 to 3100 BC, over 5,000 years ago. His body miraculously ended up in such a position that his remains were largely saved from the crushing weight of the glaciers, and he and his few possessions froze into the landscape until an ice melt and some intrepid hikers conspired to make him a star. Archaeologists argued – in private, in public, in the press – about this remarkable man. Why was he up in the mountains, all alone? For a shepherd, he was lacking in traces of sheep; for a man with a fancy copper axe, he was a long way from the high-status burial places. What could have led him to die out there in the cold?

The cold had mummified his body, preserving skin, hair and even fingernails. At least 61 tattoos marked his shrunken and discoloured – but still present – skin. Researchers had everything they could possibly want to unravel the circumstances of Ötzi’s death. However, it still took 10 years and one chance find to discover that the mystery of Ötzi’s death was an unexpectedly violent one. Under the all-seeing eye of the X-ray, researchers at Italy’s South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology, where Ötzi is housed, noticed something lodged just next to his left scapula. The foreign object turned out to be a flint arrowhead, rock-solid proof that Ötzi did not come to his end under his own terms. Shot in the back, he would have bled to death relatively quickly: the arrowhead was in position to have severed an artery. The evidence for murder mounted quickly: his hands had classic defensive wounds (cuts from fending off a knife), and a blow to the head had caused cranial trauma including a skull fracture. We have long considered Ötzi’s end a sad one – on the run, suffering from wounds that would kill him in the cold and the ice. Now, even that is being challenged: recent work has suggested that he only ended up in the ice after being dislodged out of a proper grave by the forces of nature. His particular cold case is a startling example of how little we know about life in the past, and how long it takes us to build up a biography of bone, even when we have all the clues.

Interpersonal violence affects humans around the globe, regardless of age, sex or station. However, there are patterns to the violence that vary with time, culture and region. There seem to be patterns of non-lethal violence in the hunting and gathering groups of North America prior to the development of agriculture. The evidence of healed depressed cranial fractures from the Chumash and from other groups suggests that murder was not always the intent of one-on-one violence, but that interpersonal violence could vary considerably even when the end result – lumps on heads – was the same. It was adult males in the Chumash group who were most likely to have depressed cranial fractures, particularly those who inhabited the California Channel Islands, one of the more restricted-leg-room parts of the Chumash territory. By contrast, a group in Michigan had mostly adult females affected, which bends towards a theory of domestic violence against women. On Easter Island, another constrained environment, it’s the adult males again, and among prehistoric Australians, women.

It’s difficult to parse the evidence of interpersonal violence in the skeletal record. Lawrence Keeley, who wrote the influential book War Before Civilization (which we will come to in a few chapters), worked on the excavation of a Californian shell mound site in the San Francisco Bay; 30 years later, I had the same experience, albeit slightly further south in Malibu. In 2009 Robert (‘Bob’ in Keeley’s preface) Jurmain published an update of the palaeopathology of the shell mound Keeley mentions in his book. The ‘high’ levels of interpersonal aggression in the San Francisco site resulted in a little over 3 per cent of the population showing skeletal evidence of head trauma. Phil Walker studied the frequency of cranial depressions in the skulls from further south in the Chumash area, including the Malibu region, and reported a rate of nearly 20 per cent; even higher rates were reported for Baja California, further south again. This level of violence doesn’t sit well with the Chumash’s view of themselves; it also seems to contradict a narrative of prehistory as a time of peace and plenty. But the bodies found along the coast of California have bashed heads and broken arms, and some are even studded with arrowheads; this is evidence that cannot be ignored.

Archaeologist John Robb of the University of Cambridge has looked at the rates of cranial fractures reported for the Neolithic period and the succeeding metal ages in Italy. He argues that while there are more cases of cranial trauma found in the Bronze Age, leading archaeologists to suspect underlying social causes of violence relating to the growth of complex political structures and urban life, the numbers of hits-on-heads is actually misleading. He argues that if you take the number of hits versus the number of heads, it’s actually the earlier Neolithic stage that shows a ‘spike’ in violence. While it’s hard to argue that the networks of villages Robb is describing in the Italian Bronze Age are truly ‘urban’, they exist in a landscape that is increasingly connected, and some of those connections do reach all the way to the populous, stratified, craft-specialising cities of the world. Cities by necessity must have highly integrated political systems to manage the long-distance trade and exchange networks of all the things a city needs – people, food and bling – and then manage the allocation of all those resources. Their innovative social structure bleeds out into the hinterlands in various ways. Robb sees the integrated social networks of dense settlements, usually based around hierarchies of males, as actually being preventative of violence. He points to anthropological evidence that for groups like the !Kung San (discussed in Chapter 2) or the Inuit, hunter-gatherer groups in very extreme environments, the homicide rate is actually very high; this is the same argument made by Lawrence Keeley, which we will discuss further in Chapter 8. In more complexly organised groups like the Turkana pastoralists of East Africa, homicide rates are lower than average, but a full three-quarters of adults surveyed in the late 2000s reported injuries due to violence, a majority of these being to the head. Ethnography paints a vibrant picture of both fatal and non-fatal violence, with more deaths at the extreme ends of population density.

In China a survey of fracture patterns showed that the agro-pastoralists of the Mongolian frontier under the thumb of the Chinese state during the Late Bronze age actually had fewer fractures than nearby free-range nomadic pastoralists; to be fair, though, they also had iron helmets. A sample from the site of Lamadong in the early days of Imperial China, a proper nation-state if ever there was one, has fewer still. There is a school of thought that, because non-agricultural groups in the modern world are invariably in some sort of quasi-subjugation to the political forces of the world of nation-states, any violence observed in hunter-gathers is a pathology introduced by contact with Western/state/military/capitalist (delete as appropriate) forces. The skeletal record would beg to differ.

Robb sees the number of males with cranial trauma at the Italian site of Pontecagnano during the Bronze Age as signalling a lowering of interpersonal violence; city life offered a more refined way to settle arguments than blunt force. The Neolithic he finds more equal, with both men and women experiencing similar rates of cranial trauma. The rise of the tools of violence as an important cultural symbol, reflecting particular social identities and status, might actually reflect the real use of weapons in a society as symbols: not so much to kill, but to suggest the status of a killer. While his example comes from one particular site in a particular period in a particular region, it’s interesting to try to extrapolate these patterns beyond Italy. Up in the Alps, the murder of Ötzi fits into a culture and a time of Neolithic competition in the Alps that these theories suggest should have been less lethal. However, lethal and non-lethal patterns of violence can be found in many places around the world where a combination of life tied to the land and social stratification intensify the potential for conflict. Ötzi’s ravaged remains tell us at least one aspect of the story of the Neolithic that we would see in the Americas, and probably Asia and Africa too, if only we had better preservation.

But the Neolithic is the time before cities, and what we really want to know is if the brand-new urban systems that follow the development of settled, agricultural life show the same calming effect as the less-urban networks of towns and villages that Robb describes for Italy. I should reiterate the point about metal not being the harbinger of cities: much of Europe adopts metal without getting very populous and urban about it for thousands of years. The Italian Bronze Age is not quite the same as the Mesopotamian one, and just because I’m cavalierly referring to various metal ages to keep my dates straight doesn’t mean that the hoary old progressive trajectory of stone–bronze–iron–steel is applicable in even the majority of past cultures. China, for instance, managed perfectly good cities with jade at the top of their must-have list until truly global markets encroached in the post-medieval period, and the Maya never had a Bronze Age at all but certainly had cities. One of the great tragedies of archaeology is that the very first cities were largely the ones in places archaeologists’ governments had just colonised, so many of our terms – especially those for time periods – are unfairly coloured by the well-known archaeology of the ancient Near East.

While modern-day excavators may insist on a variety of ridiculous and anachronistic practices and tools,29 the science has moved on considerably since the days of pith helmets and cocktail hours.30 Where once the aim of excavation was to blitz down to the bottom of whatever pile of archaeology you had,31 yanking out the interesting bits32 as you went along and hawking your story and the goods at the end, now we have Harris matrices, finds registers and fine-tuned public engagement strategies. We are, however, still lumbered with some of the highly specific, non-universal terms for different time periods that rose out of those mud-brick mounds. Hopefully the reader will have the fortitude to wade through the morass of dates, times, periods and technologies and accept my broad divisions of the world into the non-urban Neolithic of villages, the urbanism of early cities and (when we get there) the global network of a truly urban world of connected cities, empires and states.

As something of an illustration of the widely variable experience of the interpersonal violence we have been discussing here in the past, the mighty site of Harappa in the Punjab in modern-day Pakistan existed at exactly the same time as old Ötzi, but in a radically different milieu. More of a network of villages in Ötzi’s day, by its peak in the mid-second millennium Harappa was a proper urban city containing an estimated 20,000 people. The culture that occupied the Indus Valley in the third and second millennia BC, stretching across much of the subcontinent and trading with the city-states and nascent empires of the Middle East, was once idealised as a peaceful, stately exemplar of humankind’s path towards civilisation. Because the site had long been associated with the semi-mythic theories of an Aryan Invasion, it seems that perhaps researchers had gone slightly too far in debunking that particular story of violent conquest and might have pushed interpretations of any kind of violence out of the picture. Harappa was the rainbow-tailed unicorn of the human past: an unstratified, largely equal society, whose road to complex urban society had been paved with non-violent interactions.

One person’s unicorn, however, is another’s devastating blunt force trauma to the skull. Bioarchaeological research has shown that not everyone living in the huge early urban site of Harappa had an easy time of it. A handful of such individuals (a few more of them female than male) were identified from the mixed bag of human remains excavated over a near century’s worth of archaeological digs. Under the unhelpful glaze of archaic preservative that early excavators dumped on the human remains, there were clear signs of painful and sometimes fatal cranial injuries. The number of violent injuries exceeds both the preceding, non-urban phase of the Harappa settlement as well as the record of violence from contemporary villages and isolated skeletal finds from the same region. Broken down into different periods of the city’s history, however, the evidence of interpersonal violence tells a slightly different story. The markers of violence from the bones buried at the height of the urban era pale in significance compared to the evidence of the post-urban period, when social collapse and instability seem to have upped the stakes for everyone. In this case at least, urban living lowered your chances of being hit upside the head.

What seems clear from the archaeological record is that with the end of the Bronze Age and the beginning of the Iron, the symbols of war start to be backed by the actual physical evidence of war. So while we might think of the first stages of urbanisation as actually having a dampening effect on the sort of face-smacking methods of argument resolution used in prehistoric California, it seems that after a certain point, just walking softly and carrying a big spatula is no longer enough to prevent violence. When we reach the point of proper-sized cities, with their endless need for goods and status and their endless supply of weapon-ready hands, we invent a whole new set of reasons to kill.

1 Metal doesn’t equal cities any more than tortoise shells equal inequality; it’s just one more type of thing that you can show off, trade and complicate your life with.

2 And I’ve listened to the site bronze specialist describe my own pitiful findings of bronze clothing pins as ‘not very good’.

3 Though I would argue that sports like gladiatoral combat actually count as structural violence, considering the violence done to them was by the will of the society they lived in; it’s a fine point, but tridents have three and they don’t look like something you’d chose to live by if you could avoid it.

4 Unless you count the example in Chapter 8.

5 Presumably, underwater basket-weaving was full. Thank you Orange Coast College.

6 Explained with commendable brevity by the local Chumash representative on my very first field school in Malibu, California, a remarkable woman with long, long hair and a voice like Janis Joplin, in the following terms: ‘We f*cked everyone, man.’

7 Island of the Blue Dolphins; merely one part of the California public school system’s attempt to atone for historical genocides – other required reading included Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes, the story of a girl in the aftermath of the atom bomb attack on Hiroshima. Fourth grade was a sobering year.

8 This is exceptionally interesting literature to review while preparing for your motorcycle licence.

9 Surprising no one.

10 That was the goal, anyway. One (male) member of my carpool discovered that if we hit the Malibu Starbucks at exactly the right time we’d end up in line behind Pamela Anderson, so … apologies to Professor Arnold for being late. A lot.

11 For anyone unfamiliar with the archaeology of coastal California, a great deal of it is taken up with mounds of shells that can be metres deep. The one in Point Mugu was big enough, and contained only three kinds of shell for the most part, which is pretty much the most boring thing in the world if you’re stuck with the job of sorting them (sorry, Professor Arnold).

12 Not to mention extending the pain to your wallet.

13 Fancy talk: haematoma.

14 And/or careless archaeologists.

15 Including one unassuming North London garden owned by my colleague Ros Wallduck, who has had to do a lot of explaining to the rubbish collectors. And the local butcher. And her husband.

16 This does of course include traumas like those caused by modern pursuits, such as crashing fast-moving cars into stationary objects and hurtling down snowy hills directly into stationary trees wearing sticks on your feet.

17 Even spoons. Particularly spoons – see Alan Rickman’s Sherriff of Nottingham in the unaccountably underrated 1991 classic Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves.

18 Doctors very much seem to enjoy naming newly discovered ways of snapping bones after themselves.

19 Admittedly, rarely involving frogs.

20 Or a particularly gender-neutral pattern of violence.

21 I can think of one particularly glamorous acquaintance whose years of dance training combined with a love of high heels have seen her accrue sufficient metatarsal fractures that she now has a wardrobe full of elevated flats just the right height to match a walking cast. Both sides have been worn.

22 They looked like blue Adidas sneakers but with wheels.

23 As will be emphasised further below, not all evidence is circumstantial. It is, for instance, very hard to argue with an ice pick to the head.

24 For us, not the people of the past. Obviously.

25 That said, doing it to corpses and dead pigs is considered a legitimate research exercise.

26 Note to non-UK residents: This is called ‘glassing’, and involves some inexplicable deep-seated reflex to smash your glass on a table and stab people with the shards when they annoy you. If someone offers to demonstrate this to you, consider leaving. Quickly.

27 One satisfied customer even returned for surgeries seven times.

28 e.g. the adorable baby mammoth Lubya.

29 Gin, short-handled shovels.

30 We’ve given up the pith helmets.

31 Apparently, laying light rail through a site to get the finds out was considered acceptable.

32 Read: gold.