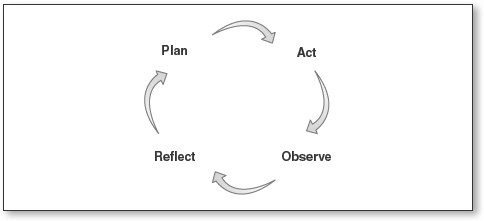

Figure 5.1 The Professional Learning Cycle

Source: Ministry of Education for Ontario. (2010). School Effectiveness Framework: A support for school improvement and student success. Toronto, Canada: Queen’s Printer for Ontario.

5

High-Impact Strategies for Secondary Schools

The challenge of transforming secondary schools has been a longstanding focus of educators and governments in Ontario. Responding to this challenge in the past decade has led the province to consider fundamental changes in what constitutes success and in the means by which educators strive to ensure this success in the educational context. Significantly, it is about how to change opportunities for students and to move toward the evolution of traditional practices to improve support for all students. This will create the conditions for success within and beyond our secondary schools.

Leadership Is the Key

To address the challenge of undertaking large-scale, systemic change for Grades 7 through 12, the Ministry of Education in Ontario first established a unique leadership network across the province, sending a clear message about the fundamental importance of the new student success strategy. In every school district and authority in the province, a new position was established for a student success leader (SSL), a senior administrator whose sole responsibility was to oversee the allocation of funding associated with the strategy and to lead the implementation of specific initiatives within that strategy. These leaders were connected directly to both the executive lead (director) of each school board and to Ministry staff and were the key contacts for all implementation initiatives for the student success strategy.

In addition to the SSL, the Ministry of Education also created the position of the student success teacher (SST). Policy/Program Memorandum 137 defines this person as a teacher designated to

know and track the progress of students at risk of not graduating; support school-wide efforts to improve outcomes for students struggling with the secondary curriculum; re-engage early school leavers; provide direct support/instruction to these students in order to improve student achievement, retention, and transitions; and work with parents and the community to support student success. (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2005)

These teachers also formed, along with school administration, guidance, and special education staff, the Student Success team in every Ontario secondary school. This team directs the implementation of the Student Success strategy and leads efforts related to the strategy in secondary schools.

The Pillars of Student Success

The change imperative in Ontario secondary schools has focused on three main themes: building foundational skills in literacy and numerical literacy, including a focus on instructional practices; providing a more explicit and rich menu of programs and pathways; and focusing on the individual well-being of students as a precursory foundation for achievement. The vehicle for implementing strategies in these areas has been the Student Success/Learning to 18 Strategy. The strategy has focused on these three themes through the introduction of four pillars of student success: literacy, numeracy, program pathways, and community culture and caring. An investigation of the background leading to the development of the initiative and of each pillar will serve to illustrate how the Ministry was able to work collaboratively with school boards across Ontario to raise the provincial graduation rate from 68% to 82% in only seven years, and how the percentage of students reading and writing at a ninth-grade level of literacy was raised to 85% for the province.

In 2003, the final report of an expert panel of educators, Think Literacy Success, was released to school districts. This report frames the literacy strategy by stating that

all educators have a role in ensuring that students graduate with the essential literacy skills for life. It calls on teachers, school administrators, families, community members, superintendents, and directors to work together to ensure student success . . . embedding high literacy standards and effective literacy practices across the curriculum, from Kindergarten to Grade 12. (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2003, p. 11)

The literacy strategy was intended to attain this goal in Ontario schools and consisted of training and literacy support materials based on the Think Literacy Success document, as well as a number of supports for educators. Overall, the literacy strategy focused on teacher training and resource development for the Ontario Secondary School Literacy Test (OSSLT) and Ontario Secondary School Literacy Course (OSSLC), on the provision of targeted resources for males who, the data indicated, struggled more with literacy than did female students, and cross-curricular literacy plans. Professional learning opportunities in the teaching of reading and writing in secondary education, and teacher-moderated marking sessions were developed to build capacity within classrooms.

The Ontario Secondary School Literacy Course

The OSSLC was also introduced as a support for students who had been unsuccessful in passing the provincial literacy test, the OSSLT, which was made a requirement of graduation for students entering Grade 9 in the 2000–2001 school year. The course consists of seventeen key expectations, all of which must be demonstrated by students to attain this credit.

Targeted Resources

One area of support resources was the identification and provision of male-focused and high-interest, relevant resources for students at a variety of literacy levels. Through the provision of these resources, students who were struggling with literacy could work with materials that were age-appropriate with a high-interest factor but that were created at a vocabulary level appropriate to the students’ needs.

Many districts also focused on the explicit training of secondary school teachers in the teaching of specific reading and writing skill sets outside of a curricular framework. This work had been traditionally reserved for teachers in elementary schools but was deemed necessary to best assist students facing literacy challenges in these areas.

Moderated Marking

A key activity that gained currency through the literacy strategy was the practice of having groups of teachers work together to evaluate student work, thereby improving consensus regarding the meaning of various levels of achievement and the consistency with which written work was evaluated against a common set of criteria, usually expressed in a rubric. This marking was often associated with the OSSLC or with a practice literacy test administered in Grade 9, the first year of secondary school. This allowed teachers to identify specific students who would benefit from additional support in the time leading up to the actual test in Grade 10 and the areas in which they needed assistance.

Cross-Curricular Literacy

Cross-curricular literacy simply refers to the practice of applying common teaching strategies and focus on literacy across all or multiple subject areas. This approach required teachers to work collaboratively to define the areas of focus or literacy strategies they would emphasize across the curriculum and then monitor the results. When combined with specific knowledge of student needs based on practice literacy test results or other diagnostic assessments of literacy—many districts designed their own—these strategies resulted in gains for students writing the literacy test, the principle means whereby students attain the graduation requirement in literacy.

The Secondary School Literacy Strategy

How to Re-Create These Strategies

Just as Ontario faced a challenge of helping students to meet a provincial literacy standard, literacy challenges can be identified and quantified in most school districts. The following is a series of considerations for addressing these challenges, learning from the Ontario model.

The underpinning principles of the literacy strategy center on the belief that students can attain literacy skills at Grade 9 levels and that literacy can be taught and learned effectively with the proper strategies.

Key Strategies

• A clear and explicitly communicated framework for success, including fundamental beliefs and principles, intended outcomes, and supports

• Evidence of need as illustrated by clear, student-based data to shape the development of the overall approach so that it addresses the specific needs of the district

• Resources targeted at attaining the stated outcomes

• Professional learning for teachers at all levels to address literacy instruction across the curriculum and in all grades but with a major focus leading to and including Grade 10

Political Elements

Support of education departments is helpful to align findings and to guide the development of the framework, resources, and strategies.

Reaching Teachers

The engagement of teachers and school administrators is critical in the implementation of any successful educational program. Educators must be supported with a clear vision of the intended outcome of endeavors such as the literacy strategy, an active role and opportunity to apply their experience to the development of the framework, and resources to support work in specific school and classroom plans. Professional learning, resources, and communication are required to implement this strategy successfully.

Reaching School Districts

School districts need to be supported by clear communications and funding plans, training schedules, and the resources necessary to allow teachers and administrators to access the knowledge, skills training, and tools necessary to implement the strategies outlined here.

Resources and Supports

Reading and writing instruction training, appropriately leveled resources, and funding to support the objectives of the framework generated for the school or district are necessary to successfully implement this strategy.

In 2004, the expert panel report Leading Math Success was released to SSLs and school districts. The report states that its purpose is “to help create a brighter future for Ontario adolescents who are currently at risk of leaving high school without the mathematics skills and understanding they need to reach their full potential in the twenty-first century” (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2004, p. 9). Numerical literacy continues to be an area of focus for school boards and districts across Ontario, and the recommendations of the expert panel are still in force in this pursuit.

The numeracy strategy resulted from a strong partnership between the Student Success branches and the curriculum branch of the Ministry of Education, and focuses on improving opportunities for students to acquire and demonstrate their learning of mathematics. It is supported by materials based on the Leading Math Success document and on subsequent Ministry initiatives such as Targeted Implementation and Planning Supports (TIPS) and TIPS for Revised Mathematics (TIPS4RM).

A variety of related projects and research has been implemented to assist with a focus on mathematics and numeracy instruction, including the Growing Accessible Interactive Networked Supports, Professional Resources and Instruction for Mathematics Educators and Programming Remediation and Intervention for Students in Mathematics projects, Math Critical Learning Instructional Paths Supports, and specific funding for differentiated instruction for mathematics. Additional support came from colleges through the College Math Project (2012) and research reports such as the Curriculum Implementation in Intermediate Mathematics (2007). Both the literacy and numeracy initiatives have benefited from the provision of Learning Opportunity Grant money being available to fund after-school programs for students.

Areas of Focus

The numeracy strategy focused on professional learning sessions for teachers, structured lesson design, and resource development and application, including technology applications for a variety of student learning styles. Varied projects and pilots for the math strategy implementation were funded, and resources were developed for use in the classroom. In the 2010–2011 school year, a group of mathematics educators and researchers gathered to further map out the strategy and to discuss recommendations for additional improvements. The use of collaborative inquiry—the process by which a group of educators engages in the joint consideration of student work with a goal of identifying and addressing areas of learning need for specific students in a classroom—has become an increasingly central support in mathematics instruction in the province.

The Secondary School Numeracy Strategy

How to Re-Create These Strategies

While Ontario still faces a challenge with respect to improvement of student learning in mathematics, strong steps and gains are being made in most school districts. The following is a series of considerations for addressing these challenges, based on the Ontario model.

Fundamental Beliefs

The principles of the numeracy strategy center on the belief that assisting teachers to become more comfortable with differentiated practices to meet specific student learning needs will continue to facilitate the development of appropriate strategies for student success.

Key Strategies

• A clear and explicitly communicated framework for success, including fundamental beliefs and principles, intended outcomes, and supports

• The consideration of individual student learning and the subsequent identification of specific learning needs to be addressed with appropriate instructional strategies

• Resources targeted at attaining the stated outcomes

• Professional learning for teachers at all levels to assist with the process of collaborative inquiry, engagement strategies, and the development of new lesson structures and classroom practices

Political Elements

Support of education departments is helpful to align findings and to guide the development of the framework, resources, and strategies.

Reaching Teachers

Engaging teachers and school administrators is critical in the implementation of any successful educational program. Educators must be supported with a clear vision of the intended outcomes, such as those identified in the the numeracy strategy; an active role and opportunity for teachers to apply their experience to the development of the framework; and resources to support work in specific school and classroom plans. Professional learning, resources, and communication are required to successfully implement this strategy.

School districts need to be supported by clear communications and funding plans, training schedules, and the resources necessary to allow teachers and administrators to access the knowledge, skills training, and tools to implement the strategies outlined here.

Resources and Supports

Specific mathematics instruction training, manipulative resources, diagnostic tools, the development of professional learning teams, and funding to support the objectives are necessary to implement this strategy successfully.

Instructional Practice

Although it is not technically a “pillar” of the Student Success strategy, the focus on instructional practice has grown from the pillars of Literacy and Numeracy. Any improvement in education ultimately needs to happen in the classroom. The teaching–learning relationship between individual students and their teacher is, at the moment, the defining characteristic of the educational process. Whether students and teachers make a connection on some level that allows those students to better unlock their learning potential is a critical component in systemic educational improvement.

The explicit focus on instructional practice for secondary schools has been taken up in varying degrees in schools and school districts across Ontario. This variability has required increasingly precise, specific, and targeted approaches to building instructional leadership capacity, using evidence, developing frameworks and tools for assessment, and an increasing effort to support teacher creativity within a common framework of resources and guiding principles. Outside the efforts in literacy and numeracy, four main areas of focus in these endeavors have been

• using collaborative inquiry planning processes,

• focusing on differentiated instruction with supporting resources,

• connecting more strongly to address the special needs of some students, and

• reconsidering assessment and evaluation practices.

Collaborative Inquiry Planning Processes

As schools and school districts considered the challenges of improvement in a system that has been recognized as one of the five best in the world (Mourshed, Chijioke, & Barber, 2010), and as they considered the data and evidence that were increasingly both available and abundant, the need for common frameworks became critical. The entrance into a collective consideration of problems of practice, focused on the use of (often observational) evidence and the use of research-informed practices to devise strategies to address these issues, is termed collaborative inquiry. Schools had used a school improvement plan process for years in Ontario in varying degrees to build continuity within districts, but there was no overarching provincial framework with which to work. In 2005, the Literacy and Numeracy Secretariat introduced a school effectiveness framework (SEF) for elementary schools (Government of Ontario, 2010b). The framework would evolve into a broad self-assessment tool for all schools in the province in the 2008–2009 school year. This framework focused on large-scale educational processes such as assessment and evaluation, which were relevant in all grades, and provided indicators and evidence exemplars for use at all levels of the educational system. In 2008, the Student Achievement Division of the Ministry of Education introduced a universal Board Improvement Plan for Student Achievement template that included an extensive assessment tool to help guide school districts in their reflection for planning.

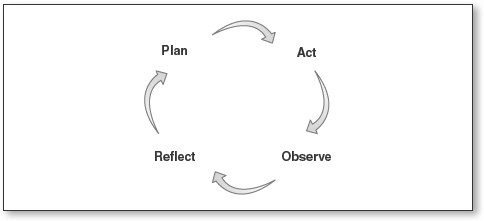

These supports and frameworks were predominantly based at the system and school levels, but they formalized a process that could be replicated in the more intimate environment of the classroom. In 2009, the Student Success strategy introduced a Professional Learning Cycle to teachers in the intermediate (Grades 7–10) and senior (Grades 11 and 12) divisions. This collaborative inquiry process, illustrated in Figure 5.1, is a simple, often represented process that can be applied to reflective practice at any level in the educational system from the classroom to the political scale. This can assist educators in becoming explicit and intentional in their practice.

Differentiated Instruction and Supporting Resources

A great deal of research, from Gardner’s (1983) theory of multiple intelligences through the work of Tomlinson (1999), Nunley (2001), and others has focused on the benefits of knowing more about and responding in explicit and meaningful ways to the diverse learning needs of the individual students in any given classroom. The consideration of student and teacher profiles in any manner of areas such as readiness to learn, prior knowledge, learning style, or multiple intelligences can profoundly change how teachers approach the task of facilitating the student’s acquisition of knowledge, information, skills, and understanding in ways that allow them to best internalize and apply that learning. Such differentiation can occur in areas of lesson content, in the processes available to students to access learning, and in the products they are asked to produce as a demonstration of that learning. Differentiation of instruction based on an understanding of the student’s need through collected and observed evidence helps educators to see new ways of creating catalysts for students to engage with their learning. They can also expand their own approaches to instruction that extend beyond their own preferred teaching and learning styles.

Figure 5.1 The Professional Learning Cycle

Source: Ministry of Education for Ontario. (2010). School Effectiveness Framework: A support for school improvement and student success. Toronto, Canada: Queen’s Printer for Ontario.

Connections to Students With Special Education Needs

One form of differentiation that has existed for some time in Ontario and that is critical to reducing achievement gaps within and among groups of students is the process of assessing areas of special need for students with exceptionalities of a developmental or cognitive processing nature, and establishing and implementing strategies to address these particular exceptionalities in addition to other learning needs. In Ontario, this work has been characterized as “special education” and encompasses a wide spectrum of exceptionalities, from students who have significant developmental delays that place them far behind their age cohort with respect to their cognitive function, to students with very high measured intelligence quotients that place them in the top few percentiles of the population with regard to this measurement of intellectual capacity. The importance of this focus is in recognizing the specific nature of the exceptionalities the student is facing, creating a series of research-based strategies and implementing those strategies to mitigate for exceptionality and optimize the learning opportunities for each student.

Assessment and Evaluation

The continual assessment of students accompanied by the requisite changes in teaching approaches, strategies, and practices to address the learning needs identified by these assessments is a hallmark of effective teaching practice. The Ontario experience has included the revision in 2008 of the assessment and evaluation policy document and the release of Growing Success (Government of Ontario, 2010a). This is a document that sets the framework for all assessment and evaluation practices and policies from school entry to the completion of secondary school. One of the key areas of focus for the document and for effective assessment practice is the delineation of three types of assessment: assessment for learning, assessment as learning, and assessment of learning, or evaluation. The distinction is an important one as it demonstrates a reinforcement of the concept that assessment of students in a classroom has a far broader scope than simply making a judgment of their work and assigning a value to that judgment to form the basis for a final grade. By embedding assessment for and as learning into the assessment policies, Ontario signaled the importance to effective instruction of self-, peer, and teacher assessments of student understanding and the capacity to demonstrate key curriculum expectations prior to evaluation—a time during which instructional steps may still be taken to enhance learning and further optimize the student’s capacity to demonstrate key learning expectations.

One important distinction when considering assessment and evaluation practices is the one between large-scale standardized assessments and less formalized assessment tools and activities. When educators conduct an assessment of student learning needs to better refine their differentiation of instruction for their students, they will use a wide variety of tools with a focus that reflects the nature of the learning needs most commonly found in the subject area or type of learning in which they seek to engage their students. These less formal tools, which often take but a few minutes to administer (red, yellow, or green card self-assessments of understanding; brief quiz-like assessments of major concepts; diagnostics of prior learning before entering new subject matter; etc.), are much more prevalent and perhaps carry a greater daily facility for the educator than the larger-scale standardized assessments (such as the Diagnostic Reading Assessment, Comprehension Attitude Strategies Interest, or Education Quality and Accountability Office tests) that may be administered. The distinction is important when discussing assessment, as often it is equated to these types of larger-scale standardized tools as opposed to the more nimble and immediate assessments that teachers make of their students on an ongoing basis in the daily practice of teaching.

The Instructional Practice Strategy

How to Re-Create These Strategies

Ontario’s journey into a strategic, focused, and consistent set of strategies in instructional practice has already provided a foundation for teacher creativity and instructional leadership to flourish. The following is a series of considerations for addressing these challenges, learning from the Ontario model.

Fundamental Beliefs

The underpinning principles of the instructional practice strategy is that excellent teaching and learning practice exists within and beyond the classrooms of Ontario and that the mobilization of knowledge about these practices and the engagement of teachers in the examination and ongoing evolution of practice will lead to greater student engagement and achievement for the learners in the 21st century.

Key Strategies

• A framework for the consideration of instructional practices

• Vehicles for the explicit organization and consideration of instructional practice

• Key resources and supports for capacity building in school, system, and classroom leaders to create and sustain a culture of continuous collaborative inquiry

Political Elements

Support of education departments is helpful to align findings and to guide the development of the framework, resources, and strategies.

Reaching Teachers

The engagement of teachers and school administrators is critical in the implementation of any successful educational program. These educators must be supported with a clear vision of the intended outcome of endeavors such as the instructional practice strategy, an active role, and opportunity to apply their experience to the development of the framework and resources to support work in specific school and classroom plans. Professional learning, resources and communication are required to successfully implement this strategy.

Reaching School Districts

School districts need to be supported by clear communications and funding plans, training schedules, and the resources necessary to allow teachers and administrators to access the knowledge, skills training, and tools to implement the strategies outlined here.

Resources and Supports

Specific instructional practice and leadership capacity-building training, appropriate resources, and the development of professional learning teams and funding to support the objectives of the framework generated for the school or district are necessary to successfully implement this strategy.

Program Pathways

Perhaps one of the key defining characteristics of the Student Success strategy in Ontario was the explicit focus on improving course and program offerings for students who were not bound for a postsecondary destination in the university pathway. The concept of creating specific pathways for students bound for apprenticeship, college, or the workplace was not new or unique to Ontario schools. The combination of an explicit focus along with a guiding expert panel report, Building Pathways for Success Grades 7–12 (Government of Ontario, 2003), helped to frame this element of the strategy and allow for the implementation of a variety of tools to assist schools. This included expanded co-op credits, specialist high skills major programs, dual credit programs, the School College Work Initiative, lighthouse projects, and broader college partnerships.

Expanded Co-Op Credits

In 2008, the Ontario Ministry of Education changed policies regarding the use of co-operative education courses, the name for courses in which students spend time in a workplace setting that is related to a course of study they have completed or are completing in the school setting. This form of experiential education provides students with a greater degree of relevant application of learned skills, develops new skills, and provides valuable experience in a work sector in which they may have an interest after completing schooling. The policy change recognized to a greater degree the importance of these courses by making it possible for them to contribute to a student’s list of compulsory graduation credits. This policy change signaled the value in the greater preparation of students for the workplace after and, in so doing, also served as a statement on the value of the workplace and apprenticeship destinations.

Specialist High Skills Major

In 2006, the Ministry started a new program for organizing curriculum and other specific prerequisites that would allow students to qualify for a new type of certification in addition to their Ontario Secondary School Diploma (graduation certificate): the Specialist High Skills Major (SHSM). The concept of the SHSM was the creation of a program at the school and community level that consisted of a specific economic sector focus and included five key elements: a bundle of eight to ten credits with the sector focus, specialized units called contextualized learning activities within courses (i.e., mathematics or English) in which applications to the sector were specifically made (i.e., tree stand density calculations in mathematics courses in a forestry SHSM), experiential learning opportunities (two co-operative education credits at a minimum), industry-recognized certifications as prescribed by Ministry documents, and the use of the Ontario Skills Passport, an employer-completed record of skills that could be used in future employment by the student. These programs, designed by schools but assessed by the Ministry for compliance with the program requirements, gave a strong focus and relevance to programming for students seeking eventual employment through any of the four major destination pathways: apprenticeship, college, university, and direct entry to the workplace.

Dual Credit Program and School College Work

A further means of strengthening programming for students who were not bound for universities involved a connection between the Ministry and the Council of Directors of Education and a program called the School to College to Work Initiative (SCWI). In particular, in 2007, the concept of a dual credit was introduced. These were special courses in which students received instruction at a community college and were able to gain credit both at the college (for future application toward a diploma program) and at the secondary school (for application toward their Ontario Secondary School Diploma). These programs are considered to be largely responsible for subsequent increases in the rate of students attending community college, especially those students who attend directly after graduation from secondary school.

Lighthouse Projects

From 2004 to 2008, the Ministry opened funding to district school boards to allow them to apply for short-term support for programs they felt would further their ability to support students at risk of not graduating or who were in risk situations. These differentiated projects were intended to allow boards to identify and address conditions of local need and to provide the Ministry with insights into successful practices to assist students. Many of the projects funded included support for students seeking postsecondary opportunities in a variety of postsecondary destinations, including apprenticeship, college, and the direct entry to the workplace.

College Partnerships

Partnerships with community colleges in Ontario have always been important in creating opportunities for students to understand, explore, and eventually enter the programs offered by these institutions. Prior to the development of the SCWI, many colleges actively sought partnerships with districts to help students to take courses associated with diploma programs at the college. Partnerships with colleges were particularly aimed at apprenticeship and college pathway students, and helped many students to “see” themselves at college and thereby act on meeting entry requirements.

The Secondary School Program Pathways Strategy

How to Re-Create These Strategies

Pathways support relies on a clearly communicated statement of value for all postsecondary destinations supported by funding and program support to create strong programs for students in that destination pathway.

Fundamental Beliefs

The underpinning principles of the pathways strategy center on the belief that despite being the pathway that most educators have taken, the university pathway cannot be held as superior to other destination pathways, and that high-quality programs in all pathways must be developed and supported.

Key Strategies

• A clear and explicitly communicated framework for success, including fundamental beliefs and principles, intended outcomes, and supports

• The explicit funding support for program development, implementation, and sustainability in all destination pathways

• Resources targeted at attaining the stated outcomes

• Professional learning for teachers at all levels to assist with the process of developing, implementing, and sustaining these programs.

Political Elements

Support and funding for program, communication, and policy development to facilitate effective pathways programming for all postsecondary destinations.

Reaching Teachers

The engagement of teachers and school administrators is critical in the implementation of any successful educational program. These educators must be supported with a clear vision of the intended outcome of endeavors, such as the pathways strategy, and be given a real opportunity to actively apply their experience to the development of the framework and resources to support work in specific school and classroom plans. Professional learning, resources, and communication are required to successfully implement this strategy.

Reaching School Districts

School districts need to be supported by clear communications and funding plans, training schedules, and the resources necessary to allow teachers and administrators to access the knowledge and skills training and the tools to implement the strategies outlined here.

Resources and Supports

Specific communication of the vision; planning opportunities that engage the school staff and partner with the broader community, including colleges, employment sector connections, and apprenticeship providers; and funding to support the objectives of the framework are necessary to successfully implement this strategy.

Community, Culture, and Caring

The fourth pillar deals with the nonacademic challenges that often have an incredible bearing on the student’s ability to engage in the academic pursuits of education. In this sense, the community, culture, and caring pillar is almost foundational to the other three pillars in that, like Maslow’s (1943) hierarchy of needs, the personal preconditions for learning must be met before many students are able to engage in their education. Based largely on the work of Dr. Bruce Ferguson’s Early School Leavers report (Tilleczek, Ferguson, Boydell, & Rummens, 2005), the title of the pillar incorporates the focus on a broader support system for students and education (community), a realization that the lives of students are diverse and need to be understood to serve those students fully (culture), and the necessity for a caring adult who will mentor, advocate for, and support each individual student (caring). The elements of the strategy focus on targeting specific students for support; the transitions strategy, including the key caring adult; academic interventions like credit recovery; and listening to students, as exemplified by student voice projects.

Related Research

Dr. Bruce Ferguson of the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, has partnered with Dr. Kate Tilleczek of Ottawa University and others to author two key reports—Early School Leavers (Tilleczek et al., 2005) and Fresh Starts and False Starts (Tilleczek et al., 2009)—that have assisted understanding of the perspective of students who have disengaged from education in Ontario and who are transitioning from elementary to secondary school. Dr. Ferguson’s summary of the necessary response to the early leaver study has been both simple and profound: Be proactive in helping to reduce and prevent barriers to success; be more understanding of the lived experience of youth, especially where it deviates from that of educators; and be more flexible in helping students address their needs. The report also modeled the practice of listening to the voices of students as a key source of evidence for educational decision making. The transition report similarly focused on student experience and reinforced the importance of the nonacademic experience and culture of the school environment in helping students to be successful. Other work in student engagement, such as that of Willms, Friesen, and Milton (2009), reinforces this message and the importance of the concept of student engagement as a critical precondition for success.

Targeted Students and Precise Practice

The concept of targeting students who struggle is not unique in educational research or practice. Countless studies have been done on selected groups of students and their achievement—be they ethno-cultural, gender, special education needs, achievement levels, course types, or some other criterion-based focus group. The keys to success with any focus of this nature are to remain cognizant of the learning needs of the actual individual students with whom educators are interacting and to respond to those needs through regular assessment and the implementation of research, including proven strategies to address the actual causes of the issues facing these students. The promotion of differentiated instruction, effective assessment (the process of determining what the student learning needs are), and collaborative inquiry into addressing identified learning issues are all promising steps that Ontario has taken to address the issue of differences in student achievement. Greater individualization of knowledge of student need and the development of effective strategies to address the needs is the hallmark of the most effective work in this area.

With respect to community, culture, and caring, this can include the work of the Student Success team and a broader group of teachers who in many schools hold regular conferences to address students in need of support beyond the academic sphere and the nature of that support. The Ministry of Education requests regular reports (titled Taking Stock) of students who are at risk of not graduating or who are deemed to be in risk situations, as well as an accounting of some of the strategies used to mitigate the risks facing these students. A study by Willms et al. (2009) indicates that student engagement peaks in elementary school and then declines steadily until the Grade 11, the penultimate grade of secondary school, at which point there is a very modest increase in engagement levels. This engagement is measured by attendance, participation in school organizations (such as clubs and teams), and self-described sense of belonging and intellectual engagement.

Transitions

Part of the targeting strategy in Ontario is to focus on students in transition. While there is an increasing focus on all transitional processes associated with the secondary schooling process (i.e., grade to grade, school to care, and the reverse), the main focus has been on the transition from elementary (Grade 8) to secondary (Grade 9). In this process, SSTs meet with staff from the elementary schools to discuss student profiles and identify students who might benefit from a host of specific interventions, such as a strength- or interest-based timetable, a specific success plan, including special needs, counseling or guidance support, and the explicit assignment of a “caring adult” and sometimes a peer mentor to ensure that the transition to secondary school is as smooth as possible.

Caring Adult

The concept of a caring adult is supported by research from fields of education, youth engagement, volunteer organizations, and mental health that indicates that an adult mentor and advocate is one of the primary drivers of success for young people in transition. This also prevents students in risk situations from experiencing the negative academic consequences that often accompany these situations. Ontario schools have refined this process and often assign staff to specific students to develop a supportive relationship. In the most successful examples, these relationships develop quickly through a natural connection between the student and staff, be it a classroom teacher, counselor, coach, custodian, or secretary, education assistant, or some other adult in the educational community. In several schools, the SST will initially make the connection while this other relationship is developing. These people monitor the student’s progress and keep an eye out for any situations or conditions that develop and that may have a negative impact on the student, and then participate in the facilitation of appropriate supports and interventions for that student.

Credit Recovery

One of the interventions that was created to support students in reducing barriers to graduation but that still honors the rigor of the requirements necessary for graduation is credit recovery. Although the principle of credit recovery has been in Ontario education policy since 1999, it was explicitly articulated after 2005. The principle of the intervention is that when students do not demonstrate the Ontario curriculum expectations of a given course to a sufficient degree, they will receive a failing grade and will not be awarded a credit in the course. As Ontario requires thirty credits (eighteen of which are mandated or compulsory courses) for graduation, this represents a significant setback in the path to graduation for the student. When the research (King, Warren, King, Brook, & Kocher 2009) shows that failure of even one course in secondary school significantly increases the chance of not graduating, the importance of recovering failed credits becomes apparent. The repetition of entire courses failed has been and somewhat remains, a common practice in Ontario schools. Credit recovery is a process in which teachers identify which expectations the student did not successfully demonstrate when failing a course, and it is only those expectations that form the focus of the credit remediation process. This reduces the time necessary and allows students to regain multiple failed credits in a time span during which they might only regain one credit if they were to repeat an entire course. In this way, the student can demonstrate the expectations successfully, still complete all of the academic work necessary to allow for legitimate credit granting, and yet not spend an inordinate amount of time completing graduation requirements and developing the hopelessness that often accompanies attempts by older students with lower credit counts to pursue graduation.

Student Voice, Including SPEAK UP

One of the hallmarks of the Ontario strategy for the educational engagement of students is the element of listening to the student voice. While the concept of student government is a popular one in North America, the student voice initiative has a broader mandate of engaging the thoughts of all students, including groups of students who might not normally get a voice in their school. Student voice as described here and as practiced in Ontario schools in the most part refers to the involvement by students in some forms of school change. Schools, bounded by legislation and both government and local policies as they are, are traditionally places in which adults are expected to create and enforce the expectations, limitations, and operating procedures for all school community members. To mitigate the sense of disengagement that this can sometimes create for students participating in the community, many forms of student governments, often modeled on existing adult political structures, have been created in schools. Ontario has even gone so far as to allow a student trustee (elected by other students of the school board) to sit as a trustee at meetings of the school board. This, of course, is student voice at work; the students having a place at the highest tables where decisions are debated and ultimately decided (although the student trustee does not get a vote, as he or she is not technically a publicly elected member of the school board)—but was this voice representative of all of the students?

Student voice is about intentionally engaging with students on matters where they can legitimately have an influence on outcomes concerning the educational environment in which they will learn. Furthermore, student voice is about intentionally seeking out the voices of students who are typically not heard. This includes the voices of the disengaged, the underachieving, the poor attendees, the nonparticipants, and the oppositional students. Student governments will often engage the voices of those students who value and usually flourish within the existing system. Student voice also focuses on hearing from those for whom the system is not working. When their voices can be heard and, ideally, their intellect engaged in the process of their education and the environment in which that occurs, we are most likely to create changes that will benefit a greater range of students. Such changes and the assumed engagement increases should lead to greater success for all of our students with the concomitant gains in achievement and school completion that we are seeking for our society’s benefit.

SPEAK UP seeks to address the many means by which the voices of students can be heard and meaningful contributions can be made to decisions about schooling and education. The initiative consists of three key elements: student voice projects, the Minister’s Student Advisory Council, and student forums. The student voice projects allow students and school staff to receive funding for a project that they feel is important to the improvement of their school from a student’s perspective. While many elements of the education system in Ontario are beyond the scope of students (and often staff) to change, there are many elements of the education experience that students can influence, shape, and change. These projects assist in allowing these changes to occur and for students to become more highly engaged in their school experience by developing a real sense that their thoughts and ideas matter, and can influence and bring about positive change.

The Minister’s Student Advisory Council (MSAC) is a group of sixty students who are selected for positions on a council that discusses issues of importance and who meet twice annually to provide direct feedback to the elected minister of education. Begun in 2008, this council is intended to model the importance of student input to changing the educational environment from the highest provincial level to the classroom. The group has already made suggestions that have resulted in policy changes for education in Ontario and thus demonstrates the power of the concept. The group is intended to be representative of the spectrum of students and student experiences across the province.

Student forums take various forms but are regionally focused sessions in which a larger sample of students are brought together to discuss and make suggestions on issues of interest to them. It was one such set of forums that led to the suggestions by the MSAC that resulted in policy changes to Ontario’s approach to graduation requirements. For instance, the council advocated for a policy change to allow students to begin accumulating the forty hours of community involvement required for graduation in the summer between Grades 8 and 9. Previously, students had to wait until they had begun Grade 9 to start accumulating these hours. As older students often have more demands on their time, including part-time jobs, this change was considered and accepted, and the policy was changed.

Recently, the focus of the forums was adjusted slightly to encourage students to engage in action research on issues of importance to them. Some of the initial projects suggested indicate that these research-focused undertakings may provide deep insights into meaningful and relevant topics that could represent significant change opportunities for students in risk situations. These forums allow the Ministry of Education to gather student input to inform their policies and actions. At a school level, there is also a product called SPEAK UP in a Box, which allows students to run a school-wide forum following the same process and to have input on their own school’s issues.

Student Choice

Choice in what we choose to study or pay attention to in life is a fundamental need for adults and students alike. The greater our options are, the more likely we are to be engaged in making those choices. Options for students must be carefully considered by school and system administrators. While much of the educational experience is determined by government policies, rules, and legislation, and further refined by local school district policies and rules, there are areas in which flexibility and options may be developed. The system in Ontario and elsewhere also has a tendency to prescribe the course and curriculum content for students in the early years of their secondary education before opening the options more broadly in Grades 11 and 12. The transitions strategy and work supervised by Dr. Bruce Ferguson, discussed earlier (Tilleczek et al., 2005, 2009), illustrate that students need flexibility to be fully engaged in their own education and subsequently to have the optimal opportunity to be successful in that education. Student choice may be ingrained in the operating processes of a school or a district (student governance structures, opportunities for students to be heard in a meaningful way, course options, and specialized program choices), but it may have the greatest impact at the classroom level. In the classroom, a teacher who is continually assessing student learning needs and differentiating the instruction to provide students with choices as to how they engage with the learning topics and materials will allow for the greatest degree of flexibility and choice for students. The work of Tomlinson (1999), Nunley (2001), and others indicates that such differentiation will result in greater success for students.

On a school level, options for students to explore areas of high interest and skill early in their secondary career will inevitably lead to greater engagement and success. An example of this is the strength-based timetable approach for students entering Grade 9, the first year of secondary school. Strength-based timetables work by using knowledge of the student’s strengths to create a timetable of courses that best align with those strengths. Given the importance that Dr. Alan King’s (2003, 2005) studies put on attaining all credits in the first two years of high school as an indicator of graduation success, this form of choice becomes very important. Similarly, schools in Ontario have the ability to apply for funding to support specialized programming in the senior years of secondary school: the SHSM program described earlier that offers students a chance to explore a specialized pathway toward an employment sector or sectors that engage them. Students need choices to become optimally engaged in their education, and these programs represent some of the ways in which this can be accomplished.

Student Success Teams

As described previously, the Student Success team is responsible for all aspects of the Student Success strategy and its implementation in secondary schools. These teams provide an excellent leadership focus for the strategy and are a group with whom the Ministry and SSLs can work to leverage change in secondary schools. Ideally, the teams expand to include other staff beyond the four indicated by policy, and the work of student success is internalized by all staff in the school. To a large extent, the degree to which this occurs mirrors the extent to which student risk is minimized and achievement outcomes are maximized.

The Secondary School Community Culture and Caring Strategy

How to Re-Create These Strategies

The consideration and mitigation of nonacademic barriers to success remain a challenge in all educational systems. Strong steps and gains are being made in most Ontario school districts. The following is a series of considerations for addressing these challenges, learning from the Ontario model.

Fundamental Beliefs

The underpinning principles of the community, culture, and caring strategy center on the belief that all students can learn and that the nonacademic component of readiness to learn needs to be an important area of focus. Often, the role of educators is one of facilitation to support students through the access of other services.

Key Strategies

• A clear and explicitly communicated framework for success, including fundamental beliefs and principles, intended outcomes, and supports

• The consideration of individual student situations and the subsequent identification and facilitation of appropriate supports

• Partnerships with a broader service community

• Targeted focus on students at risk of not graduating or in risk situations, and a dedication to ameliorating these issues

Political Elements

Support of education departments is helpful to align findings and to guide the development of the framework, resources, and strategies.

Reaching Teachers

The engagement of teachers and school administrators is critical in the implementation of any successful educational program. Educators must be supported with a clear vision of the intended outcome of endeavors, such as the community, culture, and caring (including transitions) strategy; and opportunity to actively apply their experience to the service of students and their families. Professional learning, resources, and communication are required to successfully implement this strategy.

Reaching School Districts

School districts need to be supported by clear communications and funding plans, training schedules, and the resources necessary to allow teachers and administrators to access the knowledge, skills training, and the tools to implement the strategies outlined here.

Specific transitions and support training, targeted focus sessions aimed at assisting students, and the development of professional learning teams and funding to support the objectives of the framework generated for the school or district are necessary to successfully implement this strategy.

References

Gardner, H. (1983) Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. New York: Basic Books.

Government of Ontario. (2003). Building pathways for success: Final report of the Program Pathways for Students at Risk Work Group. Toronto: Queen’s Printer for Ontario.

Government of Ontario. (2010a). Growing success: Assessment, evaluation, and reporting in Ontario schools. Toronto: Queen’s Printer for Ontario.

Government of Ontario. (2010b). The K–12 School Effectiveness Framework: A support for school improvement and student success. Toronto: Queen’s Printer for Ontario.

King, A. J. C. (2002). Double cohort study: Phase 2 report. Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Education.

King, A. J. C. (2005). Double cohort study: Phase 4 report. Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Education.

King, A. J. C., Warren, W. K., King, M. A., Brook, J. E., & Kocher, P. R. (2009, October 20). Who doesn’t go to post-secondary education? Final report of findings. Toronto: Colleges Ontario. Retrieved from http://www.collegesontario.org/research/who-doesnt-go-to-pse.pdf

Maslow, A. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396.

Mourshed, M., Chijioke, C., & Barber, M. (2010). How the world’s best educations systems keep getting better. New York: McKinsey & Company.

Nunley, K. F. (2001). Layered curriculum: The practical solution for teachers with more than one student in their classroom. Kearney, NH: Author.

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2003). Think literacy success: The report of the Expert Panel on Students at Risk in Ontario. Toronto: Expert Panel on Students at Risk in Ontario.

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2004). Leading math success: Mathematical literacy Grades 7–12: The report of the Expert Panel on Student Success in Ontario. Toronto: Expert Panel on Students at Risk in Ontario.

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2005, June 27). Use of additional teacher resources to support student success in Ontario secondary schools (Policy/Program Memorandum 137). Toronto: Government of Ontario. Retrieved from www.edu.gov.on.ca/extra/eng/ppm/137.html

Suurtamm, C., & Graves, B. (2007). Curriculum Implementation in Mathematics (CIIM): Research Report. Report prepared for distribution to school boards. Ottawa, Canada: University of Ottawa.

Orpwood, G., Schoolen, L., Leek, G., Marinelli-Henriques, P., & Assiri, H. (2012). The College Math Project Final Report: Toronto, Canada: Seneca College Applied Arts and Technology.

Tilleczek, K., Ferguson, B., Boydell, K., & Rummens, J. A. (2005). Early school leavers: Understanding the lived reality of student disengagement from secondary school. Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Education.

Tilleczek, K., Laflamme, S., Ferguson, B., Edney, R., Girard, M., Cudney, D., et al. (2009). Fresh starts and false starts: Young people in transition from elementary to secondary school. Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Education.

Tomlinson, C. (1999). The differentiated classroom: Responding to the needs of all learners. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development.

Willms, J. D., Friesen, S., & Milton, P. (2009). What did you do in school today? Transforming classrooms through social, academic, and intellectual engagement (First National Report). Toronto: Canadian Education Association.