20

Criteria for the Part 3 Hero’s Attack

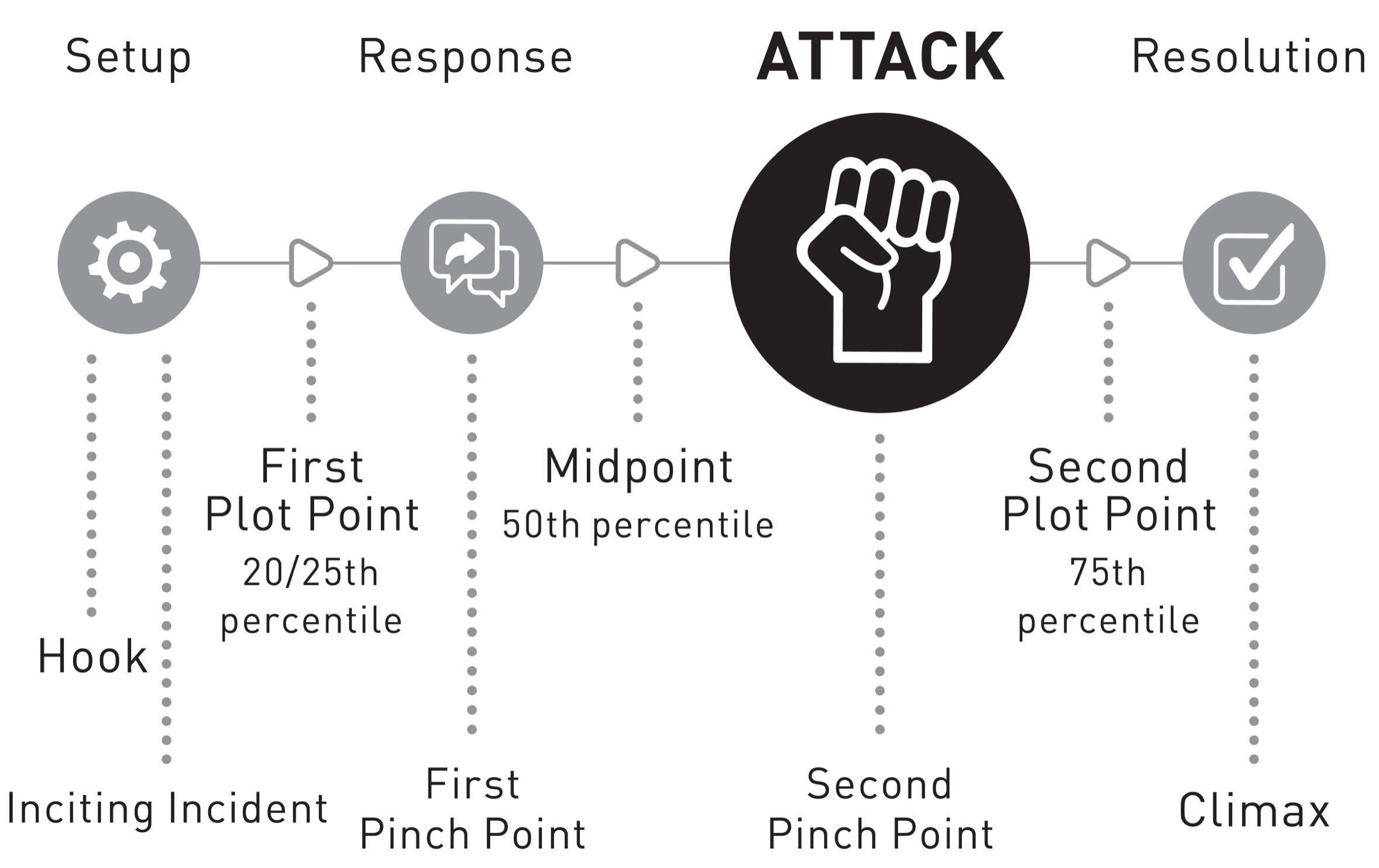

The Third Quartile of the Story

It’s fair to say that up to the Midpoint shift in the story, the term “hero,” as applied to your protagonist, may be less than obvious or clear. He’s been wandering, stumbling, getting socked in the face (literally or metaphorically) for the last 200 pages or so. Helpless or victim are better adjectives here. That’s because back in Part 1, the protagonist—not yet having earned the nametag of hero—wasn’t yet fully engaged, if at all, with the macro-story’s core dramatic question and its inherent need and threat. Your protagonist was an innocent relative to the forthcoming dramatic tension, a metaphoric orphan from what lies ahead. But because of the FPP, he is an innocent or an orphan no longer. He is in the thick of it, getting pummeled as things seem to get worse and worse in the second quartile block of scenes, where contextually she is wandering through options, hazards, and choices.

After the FPP launches the hero into that core dramatic macro-arc (thus transitioning the story from Part 1 into the Part 2 scenes), beginning with a block of scenes that show the experience of the protagonist’s response to the call to action, we aren’t yet seeing what you would normally describe as overtly heroic decisions and actions. If for no other reason than the protagonist under fire and pressure doesn’t yet possess all of the information necessary to formulate a heroic response.

It’s high time we get the hero into the game in a more meaningful way. That’s what the criteria for the Part 3 block of scenes do for the story.

As we learned in the last chapter, the Midpoint launches the players and the reader into the new context for the Part 3 quartile, which is a more proactive attack on the problem at hand. It is here in the third quartile, with its new warrior character context, that the hero begins to earn the right to put that label on her name tag.

The facilitation of a shift into warrior mode

Nothing about either the dramatic or character arcs should be random or simply inevitable. Which means something needs to emerge as a catalytic force—something that when perceived, or thrust upon the hero, shifts him into a higher, more proactively productive gear. It’s like a sick person is suddenly on the mend. A fighter without a weapon finally finds one. A person without a friend encounters an ally. You could say that until the Midpoint, the story was happening to the hero, and now, beginning with the first scenes in Part 3, the hero is happening to the story.

In Part 3, the hero becomes a warrior, if you will. It may not click at first, and certainly, the story has more surprises to offer, but now the readers have even more exciting things to root for, manifesting through decisions and actions and opportunities, because there is hope and strategy for an outcome that allows our hero to resolve the problem and fulfill the quest. With enough courage and cleverness, a new road to success awaits, even as the villain is upping her own game in the meantime.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. An upped game from both sides is the stuff of Part 4. Let’s linger here in Part 3 to make sure the groundwork we are laying delivers a vicarious experience saturated with emotional resonance.

CRITERIA FOR THE PART 3 ATTACK (WARRIOR) QUARTILE

Get ready for your weary protagonist to get her hero on.

-

PART 3 CRITERIA #1: THE HERO’S PART 3 DECISIONS AND ACTIONS LEAN INTO THE PROACTIVE, (rather the reactive context of Part 2), leveraging new information delivered at the Midpoint. This shifts the context of the entire second half of the story. Because of new information put into play at the Midpoint, the path ahead is now clarified and more strategic. The hero moves forward in accordance with that higher understanding. The pace quickens. The need for action may be more urgent now because the threat has escalated and may be closer at hand. Whereas the context in Part 2 was responding to what happens, the Part 3 scenes show a context of attacking the problem.

But, as they say, it ain’t over yet. Because the villain may be aware that the hero is now more woke and in response ups her own aggressive effort to block the hero’s path. Or not, the hero may simply up the ante, by virtue of showing up differently. In either case, confrontation becomes inevitable.

-

PART 3 CRITERIA #2: IN PART 3 THE HERO BUILDS ON PRIOR DEFEATS, FEARS, AND LESSONS LEARNED. This combines with the new Midpoint information to inform the hero’s decisions and actions going forward. If nothing else, the hero may have learned things about the antagonist or villain, the situation, the story world, or about themselves (inner demons surfacing under pressure) in the Part 2 scenes that came before. Part 3 is where she applies that learning, and the new information, to show up with greater courage, keener strategy, a bold opportunity-seizing aggression, and the general proactivity that redefines the hero’s journey and quest. In historic battle stories, this is where the hero attacks the castle of the villain. If Part 2 was imbued with a sense of hopelessness, Part 3 is where the reader begins to sense that maybe there is a pathway toward success, after all, along with a sense that there is a willingness to pay the price to get there.

-

PART 3 CRITERIA #3: In the midst of hope and higher levels of learning and efficacy, the Part 3 pathway becomes steeper and the threat darker and more urgent—because the villain isn’t backing off. An easy mistake here is to show your hero coming out swinging and succeeding early in Part 3, but the rounding of the corner needs to be wider and more fraught with setbacks than these criteria might imply.

Both Parts 2 and 3 are designed to show the hero plodding treacherous, even torturous ground, the difference being a more hapless response (Part 2) versus newfound proactivity (in Part 3) that is more courageous and strategic, based on a greater awareness of the problem and the nature of the villain. It’s like a team that is far behind at halftime, but they come out really strong afterward, and even though they’re doing well, they’re still chasing the win.

This new knowledge eventually steers the hero toward hope rather than fueling immediate success, but as the author of this sequence you need to show your hero earning whatever success comes as a result.

-

PART 3 CRITERIA #4: DRAMA, STAKES, AND PACE ESCALATE WITHIN THE PART 3 BLOCK OF SCENES. This is the consequence of the preceding criteria. Within the eight to twelve scenes in Part 3 (a number which varies greatly, according to scene and macro-story length), you may have as many as three different dramatic sequences that take the story deeper into the dramatic proposition. These sequences should include at least as many hero-driven attempts to further her goals as there are villain-driven strategies.

-

PART 3 CRITERIA #5: PART 3 INCLUDES WHATEVER MECHANICAL, CONTEXTUAL, AND SITUATIONAL SET-UP sequences are required to put the forthcoming Second Plot Point (SPP)—which is the turning point between Parts 3 and 4, where context will shift yet again—into play. Any necessary foreshadowing that will inform Part 4 beyond the SPP should also be woven into these Part 3 scenes. If the walls of the villain’s fortress have a weakness, we should have seen that foreshadowed earlier, before the charge commences.

-

PART 3 CRITERIA #6: IT’S TIME TO UNLEASH YOUR MAIN CHARACTER’S INNER HERO. Not everything your hero decides and does in Part 3 will work, or at least be fully successful. Your villain isn’t giving it up easily. But, your mission here is to allow us to experience the inner heroic essence of your hero through those decisions and actions. There is an art to this; it isn’t an on-the-nose proposition. The Midpoint shifts may not have been good news; they may add to the threat and pressure. Either way, though, your hero now has something to leverage or use that puts him back into the game in a bigger, more urgent, more meaningful way than before.

-

PART 3 CRITERIA #7: THE FINAL PART 3 STORY BEAT (SCENE) IS OFTEN A LULL. This is an all-seems-lost context, even though the hero has emerged as courageous and heroic. Sometimes things just don’t work out, and it appears, for a moment, that this is the case for our hero. It’s critical that the villain ups the ante as well, and the net result of that might find your hero in a corner. She will come out fighting, of course, but that’s what Part 4 is all about. The author is always pulling the strings of the reader’s emotional engagement, and when you end Part 3 with something dire, that gives you even more room for your hero to rise to the occasion later, when the final quartile brings it all to a resolution.

A fresh case study to witness Part 3’s context at work

Let’s take a look at The Girl on the Train (again, spoilers follow), a massively character-driven psychological thriller with three different unreliable first-person narrators that keep the reader on her toes and often in the dark. This 2015 novel was a #1 bestseller by British author Paula Hawkins.

There’s the setup. We meet protagonist (Hero? We’re not quite sure for the duration of the story) Rachel Watson (played by Emily Blunt in the film) in her bleak post-divorce life, now an unemployed alcoholic who has burned all her bridges and has little by way of hopes or dreams. To give the illusion of having a job to which she commutes, she boards the same local train each morning, sitting in the same seat to gaze out the same window every time, marveling as the real world whisks by, vicariously gazing at beautiful and perfect lives unfolding within all these beautiful and perfect houses. One of them was hers before she blew up her life and got divorced.

And so, she drinks every day, to excess, as her life slips even further into darkness.

Thus begins a very intimate narrative full of flashbacks and expositional reverie from all three of the main players, which include Rachel, her husband’s new wife, and the babysitter they employ. Other characters, who become critical to the convoluted plot, show up in these little memoirs which add up to a layered murder mystery. This deception goes on for six months, riding the train every morning, drinking in town all day, then riding the train back to her lowly abode near her old life—and nobody is the wiser. Because nobody is paying any attention to Rachel Watson.

One day Rachel sees something disturbing from her seat on the train (a key inciting incident that looks and smells like a FPP, but isn’t, if nothing else than because it’s too early within the exposition). On the balcony of the house three doors down from where she used to live, she notices Megan, the babysitter employed by her husband and his new wife, Anna—Megan is married, by the way, and Anna is pregnant—canoodling on the balcony of her house with a man that Rachel suspects is not her husband. She isn’t sure who it is. A few days later, Megan goes missing. Rachel goes to the police to report what she saw but is turned away as a crackpot. After making waves in other places, the FPP arrives (dead on at the twenty-first percentile, on page 67 of 326 total pages) when an old friend calls to tell Rachel that the police are at her house, looking for her. Suddenly she is a person of interest in the disappearance of Megan (which layers on the threat and tension for her), because she is the only witness who came forward to say she’d noticed something not right in Megan’s life.

At the Midpoint (on page 158; if you do the math, just prior to the optimal fiftieth percentile target), Megan’s body is found. The story-altering news is that she was pregnant when she was killed. That goes to motive, and it connects to virtually anyone on that list of players. The police come for Rachel, suddenly very interested in what she has to say. Her ex-husband; his new wife, Anna; Megan’s rough-around-the-edges husband; and Megan’s shrink (as well as two different strangers Rachel meets on the train) are all in play as possibly threatening, complicit villains. But the spotlight is on Rachel, and only she can get herself out from under the glare of suspicion.

This is all context for how the Part 3 quartile plays out. It’s a new context of the hero attacking the problem, fueled by new knowledge that narrows her vision toward the truth. Rachel is not going down without a fight, but now she is fighting for truth and justice for the murder of Megan and her unborn baby. It’s a fight not only for justice, but for her own resurrection of a person of worth and purpose. Her proactivity takes the form of cultivating relationships with Megan’s husband, who is angry to the point of violence, with the victim’s shrink, who had an affair with Megan, and with the police who have not quite cleared her and aren’t patient with her involvement. Gradually the shadows of the truth become evident, especially in the minds of astute readers of mysteries and psychological thrillers, among which The Girl on the Train is one of the best.

Part 3 ends at the SPP (on page 246 at the seventy-sixth percentile mark). Notice that all of these key transitional milestones appear as if Paula Hawkins herself had invented this structural paradigm; she didn’t. She just applied it to her story and tapped into its inherent dramatic potential. Perhaps she did so instinctually, perhaps during a revision, or perhaps it was something she learned to do.

That SPP was forensic verification that Megan’s widowed husband was not the father of the child that died with her, which is a game-changer (the consistent hallmark of both plot points). This ignites a fuse that burns a path to the feet of the real father, who, amidst a continuing question as to who might have killed Megan, is suddenly an injured animal in the headlights coming his way, with Rachel (this is a metaphoric teeing up of the resolution) behind the wheel.

Killer stuff. And an example of how once you are aware of the principles of these criteria-driven story elements, the best way to learn how to use them is to verify and witness their magic in the bestselling work that owes its success to the author’s abilities to wield their power—power that is ultimately available to all who seek to write stories that work, simply by leveraging the criteria that apply.