No wonder the trends of the sixties blurred the Catholic woman’s self-concept and left her validly disturbed about her role. Was her life of service to her husband, her large family, her parish and church organizations no longer enough for a fulfilling life?

Antoinette Bosco, “What’s Really Happened to Women?” (1971)

The quotation that opens this chapter, with its pointed central question, came from an article published in Marriage, a magazine for Catholic couples. It was accompanied by a photo of Betty Friedan flanked by protestors, one of whom carried a sign that read, “Unpaid Slave Laborers! Tell him what to do with the broom!!” Yet the brief bio for Antoinette Bosco, the piece’s author, could not have seemed in greater contrast: “Mrs. Bosco, mother of six, is the staff feature writer for the Long Island Catholic.” The inflammatory photo had very little to do with the article, but what lay within was much more intriguing—and rarer—than a seemingly staid Catholic woman espousing feminism, even in a mainstream Catholic magazine. What Bosco offers is a reflection on laywomen and women’s liberation over the course of the 1960s from the perspective of a moderate Catholic laywoman with feminist leanings if not a feminist identification.1

Her main argument was that “the jarring noise” of “women’s lib,” as she termed it, was “drowning out the other, the quiet-revolution that was nurtured among the female 51 percent of the United States’ population during the sixties.” She could, in fact, have been describing the laywoman project directly for Marriage’s readers. “The quiet revolution is the one to watch,” she insisted, “for it starts—not with the flamboyant demands of Women’s Liberation—but in the very depth of woman and her evolving vision of who she is. . . . Sometimes vocal in their protests, sometimes unaware that they were in revolution, American women made the sixties the decade for persistently demanding a new image of woman in the modern world.”2

Lest we imagine that Bosco was simply reporting on what was happening around her in the secular world as a detached observer, most of the article was concerned with her own community of Catholic women, whom she identified as participants in this quiet revolution. Laywomen were in the process of reassessing every aspect of their identities from working outside the home (“‘Working mother’ was almost synonymous with every form of social evil existing,” she recalled) to their sexuality (“Changing attitudes about women’s sexual role were bound to result from the popularity of a pill that placed a woman in control sexually”) to motherhood (“The declining birth rate and the new emphasis on a woman having status because of who she is and not on the fact that she’s somebody’s mother, has indicated a coming ‘deglorification’ of motherhood and large families”) and, finally, to their identities as Catholic women in an unjust church (“Another area notoriously closed for women leaders is religion, with virtually no administrative or theological positions open to women in the Church. Yet, the question of ordaining women must be faced”).3

The editors chose as the header for the body of the article, “Many of the changes create confusion for the Catholic woman,” but this was not in keeping with the spirit of the piece. Antoinette Bosco was not confused, and, despite the magnitude of the changes they were facing, she did not think the majority of her fellow laywomen need be confused either. While she conceded that some of these shifts in identity were disconcerting, even “disturbing,” she clearly thought the developments of the previous decade were fruitful and must continue. According to Bosco, the 1960s showed that Catholic laywomen knew exactly how to process these changes and become something new, through what her article termed “a personal look at women by women.”4

This chapter documents the transformations in identity that Antoinette Bosco describes through a deep dive into Marriage magazine from the early 1960s through the mid-1970s. Unlike the first two chapters in this book, this chapter turns the focus away from women’s organizations to a different kind of community of laywomen in order to investigate changes to laywomen’s self-conception. Marriage, a publication more than usually preoccupied with changing gender roles (to put it mildly), could not stop talking about Catholic women and how they were changing in the face of the modern world and church. Its editors could very easily have handed the conversation to those entrusted with such issues in the past: clergy, male Catholic theologians and social science professionals, and a handful of female freelance writers affirming the virtues of complementarity.

Instead, they became supporters of the laywoman project—at times perhaps unwittingly—by fostering lively, protracted conversations about every aspect of Catholic women’s lives, most especially in the intimate areas of home, spousal relationships, work, and bedroom, subjects that the Catholic women’s organizations in this study rarely discussed. While both men and women participated in these conversations, I have largely focused on the voices of laywomen, so abundant in this forum. Bosco could have been speaking about Marriage itself when she bore witness to the revolution so quiet she felt the need to document it in 1971 in case her readers had not noticed it had taken place.

The changes may have been gradual enough that readers had missed them, but a systematic analysis of the magazine’s articles on gender identity does indicate change over time, just as Bosco claimed, and shows that these changes were of laywomen’s own making. Laywomen had ideas to explore on many subjects relating to their own gender identity, but the common theme is a steady erosion of the foundations of the teachings of complementarity. In 1961 complementarity was unquestioningly accepted in the magazine; by 1975 this was no longer the case. What was once fixed, unchanging, and sacred—and furthermore, offered as consistent justification for denying self-determination, opportunity, or authority to laywomen—was now openly challenged in all of its manifestations. In Marriage, the laywoman project set its sights on Catholic homes and the marriages within them, calling into question the worldviews that formed laywomen at midcentury and continued to confine them.

Marriage magazine was a monthly periodical published by the Benedictines of St. Meinrad Abbey, Indiana, under the auspices of Abbey Press starting in 1959. The magazine seemed designed to appeal to educated white Catholic couples negotiating the tricky questions confronting middle-class Catholics in the “modern world.” In its earliest years, readers could find in its pages articles on suburban parish life, the Second Vatican Council and its implications for marriage, and excerpts from the works of major European theologians. They might just as likely find an article on parenting teenagers, a comic piece about the chaotic daily life of a housewife, or a debate on the question of limiting family size.

Marriage reflects a desire both to inform a readership that felt empowered by the lay action movements of the postwar years and to create a forum for debate where laypeople, male and female, could speak openly on a variety of topics of concern. The editorial team also hoped to reach young people preparing for marriage or who were newly married, and train them to this particular idea of active citizenship in the Catholic community. While Marriage had no formal ties to movements such as Cana or the Christian Family Movement (CFM) it is fair to say that the magazine shared a similar outlook at its founding and sought the same audience. Throughout the years in this study, Marriage occasionally checked in with each movement, generally reporting favorably on developments in both for its readership. While the magazine carried a whiff of CFM about it, the connection should not be overstated. Marriage viewed itself as its own creation, and its readership did not seem to identify firmly with any one movement (or indeed, with any movement at all). Marriage’s circulation was modest, but it did see an increase over the course of the 1960s. As of 1963, circulation stood at 65,000; it reached 80,000 by 1968.5

The magazine underwent a few notable changes over the course of the 1960s and early 1970s. For example, the magazine gradually moved from clerical to lay leadership, appointing a lay editor for the first time in 1966. This transition would prove permanent. In that same time period, featured experts on a variety of topics shifted from predominantly clergy to predominantly lay. Over time, the fields from which these experts came gradually transitioned from theology to the social sciences, especially psychology and sociology. Further changes are reflected in the magazine’s subtitle. What began its life as The Magazine of Catholic Family Living had become by 1966 The Magazine for Husband and Wife, signaling a change in direction and a warning, perhaps, that Catholic moms and dads best keep it off the coffee table from here on out. Not coincidentally, perhaps, 1966 is also the year that Marriage ceased to include discussions of rhythm as a viable form of family planning for Catholic couples and turned toward new conversations about Catholic marital sexuality.6

On its surface, Marriage may seem an unlikely vehicle for investigating how the American Catholic community debated questions of women’s identity in the context of their intimate lives, particularly if one’s focus is laywomen’s agency. From the beginning the positions of editor and managing editor were filled by men. Although Catholic laywomen did work as associate editors and served on the advisory editorial board, they never had editorial control of the magazine. Marriage also published its fair share of aggressively essentialist articles as well as blatant antifeminism that explicitly called for women’s submission. Why turn to such a publication to reconstruct a debate about women and their sense of themselves within their families and relationships?

As is evident in the previous chapters in this book, the women’s organizations in this study largely steered away from issues related to married women’s home lives in the 1960s—at least publicly—so their records are not helpful in this area. They discussed their changing ideas of Catholic womanhood as they related to vocation, renewal, authority and hierarchy, prayer, liturgical change, and women’s place in the church. For the most part, however, they did not sustain conversations about more personal matters, such as spousal relationships, women’s domestic lives, and sexuality. If we want to know more about Catholic women at home, we need to leave the conferences, board meetings, and newsletters behind.

Curiously, one can’t look to the Catholic feminist movement, in its ascendency in the same period, for answers in this area either. Women religious and Catholic theologians (often one and the same), who were dominant in the movement’s leadership had different preoccupations in this period, and they were unlikely to raise domestic issues as most pressing. Moreover, lay Catholic feminists seemed to ignore these topics because, for them, the questions were already settled. Self-identified feminist laywomen took for granted that they were all in agreement on questions such as egalitarian marriage, a woman’s right to work outside the home, or the importance of artificial contraception, and as a result these issues simply did not arise.

So who did talk about shifts in gender identity in the context of domestic life and family relationships? As it turns out, these conversations were raging in Marriage, a community of mainly moderate to moderately conservative lay Catholics. These editors, contributors, and letter writers, male and female, had come of age in a postwar Catholic world that liked its laypeople active and informed, and its women at home leading the family rosary. Here is where we have ample evidence of the conflicts that arose when the rising confidence of lay action in the Vatican II era ran headlong into the destabilizing ideas of the women’s movement. These folks seemed determined to puzzle out the implications of this collision.

One does not need to look long or hard to find evidence that gender was a major preoccupation in this community. This study encompasses the years 1961 to 1975. From those years, I pulled a total of 571 articles, editorials, and sets of letters to the editor for analysis.7 Of these, there were fifty-eight articles and editorials published whose primary purpose was to discuss gender roles, generally for women. That’s a stunning average of one every three months over fifteen years. In this same period, Marriage published an additional 143 articles and editorials that in some way made an argument about gender roles for Catholic men and women, arguments, incidentally, that both affirmed and challenged the status quo. It is not an overstatement to note that the topic of changing gender roles in Catholic life was ubiquitous in Marriage.

But what can we learn of women’s self-perceptions if Marriage was controlled by men? The first answer is that the magazine is replete with laywomen’s voices, laywomen who felt empowered to make claims, build arguments, and share their opinions with the world even when their views contradicted either accepted Catholic teaching or the growing voices in support of liberation. In my sample, ninety different laywomen appeared under their own byline, or in a few cases, shared a byline with a male coauthor. Yet these were not the only women’s voices to appear in Marriage. An additional 137 women had their views published under the heading “Reader Reaction,” the magazine’s section for letters to the editor. Women were even less guarded in their views in this format than paid contributors, and the editors allowed these opinions to be published without commentary (except when they perceived an unwarranted attack on another author). In its effort to respond to and include the voices of women, especially female readers, Marriage was in step with other women’s magazines at midcentury. Though perceived to be static entities that merely perpetuated prevailing notions of domesticity, women’s magazines of the era did attempt to foster communities of women readers and writers who expressed opposing positions on questions of family life.8

As I have noted, however, Marriage was male-dominated. We must treat women’s words with care in such contexts. We do not know how much they curtailed their own thinking so as to meet gendered expectations, for example. We also don’t know how many women were unable to express their ideas because they were denied access by male gatekeepers. Throughout, we must pay careful attention to how the editors framed debates, chose topics and authors, and manipulated the presentation of women and their concerns.

My point, however, is that if we only look to female-run forums free from male authority to understand female perceptions of gender identity in the Vatican II era, we will leave out huge swaths of the Catholic community. Laywomen chose to raise these issues in a space not entirely under their own control, in part because few spaces where laywomen are entirely in control exist in the Catholic Church. Not surprisingly, historians haven’t looked for discussions of women’s liberation in spaces such as Marriage because our assumption is that they would never have taken place there. As a result, we have missed how widespread conversations about Catholic gender identity (and challenges to accepted teaching) actually were, and how openly nonfeminist Catholic laywomen expressed themselves about issues relating to their own liberation even in the most unexpected places.

As I outlined in the introduction, we know that laypeople in the American church were feeling empowered to challenge authority and accepted practice at midcentury. The signs of this were abundant: in voices raised in explicit challenge to the ban on artificial contraception (and in the sheer numbers of Catholic women using birth control), in surging interest in liturgical renewal and declining participation in confession and devotions, in groups promoting racial justice, and in flourishing lay apostolates such as CFM and Cana that encouraged lay leadership and minimized clerical control.9

Yet while the more modern lay apostolates beginning in the 1940s seemed to contribute to a steady pushback against ecclesial authority from laypeople, this move coincided with a particularly strong wave of teaching on gender complementarity that served to undercut laywomen’s growing empowerment as it strengthened laymen’s authority. As historian Colleen McDannell notes, “During the 1940s and 1950s Catholic culture reassert[ed] the patriarchal nature of Catholicism as a balance to suburban domestic life.” This was also the peak of the eternal woman, a popular quasi-theological construct designed to highlight the importance of female submission at a time when Catholic leaders feared the effects of secularization and affluence on Catholic families. Before delving into the conversations in Marriage that reflected changes in laywomen’s gender identity, it is worth investigating understandings of complementarity that were dominant in the lay apostolates that constituted the magazine’s target audience at its inception.10

Catholic teaching on gender roles was clearly and frequently stated for the benefit of Catholic couples. The essential twentieth-century starting point is Casti Connubii (1930), Pope Pius XI’s oft-quoted encyclical on Christian marriage written to outline the church’s opposition to artificial contraception and abortion. While it has been discussed primarily in that context, it also outlines expectations for male and female roles within the family in response to feminism. The encyclical goes out of its way to say that the point of marriage is not merely procreation but the “mutual molding of husband and wife, [the] determined effort to perfect each other.” But soon after, Pius XI notes that within this mutuality there is an “order of love,” marked by “the primacy of the husband with regard to the wife and children, the ready subjection of the wife and her willing obedience.”11

To clarify, he says that “this subjection does not deny or take away the liberty which fully belongs to the woman both in view of her dignity as a human person, and in view of her most noble office as wife and mother and companion.” However, “it forbids that exaggerated liberty which cares not for the good of the family; it forbids that in this body which is the family, the heart be separated from the head to the great detriment of the whole body and the proximate danger of ruin. For if the man is the head, the woman is the heart, and as he occupies the chief place in ruling, so she may and ought to claim for herself the chief place in love.” Later, in warning of grave threats to the family, he singled out “false teachers who try . . . to do away with the honorable and trusting obedience which the woman owes to the man.” Seemingly referencing feminists, he claimed they went so far as to assert that “such a subjection of one party to the other is unworthy of human dignity.” They proclaimed her free of childbearing (“not an emancipation but a crime”), free to “follow her own bent and devote herself to business and even public affairs,” and free to work “without the knowledge and against the wish of her husband.”12

Here the encyclical asserts this can only be false emancipation, unlike the “rational and exalted liberty which belongs to the noble office of a Christian woman and wife.” Moreover, “unnatural equality with the husband is to the detriment of the woman herself, for if the woman descends from her truly regal throne to which she has been raised . . . she will soon be reduced to the old state of slavery.” To the church, “rational liberty” was complementarity, the belief that men and women were simultaneously equal and different, bound by their natural God-given traits to enact particular roles in the world with equal dignity, if not equal power: “In such things undoubtedly both parties enjoy the same rights and are bound by the same obligations; in other things there must be a certain inequality and due accommodation, which is demanded by the good of the family and the right ordering and unity and stability of home life.”13

By midcentury, the teaching on complementarity had shifted away somewhat from the emphasis on the hierarchy within the complementary relationship, which frankly identified the female as subordinate. Instead, newer expressions after World War II took pains to stress women’s essential equality that could coexist alongside her difference. As religious studies scholar Aline H. Kalbian points out, however, complementarity remains hierarchical, “not so much in the sense that one party submits to the other but rather that the designated role for the female gender is one that is inherently more repressive; they often define the female primarily in terms of her role as complement to the male, as his helper.” Complementarity does not merely define gender, it also dictates the appropriate form of relationship that can exist between the sexes. Ultimately, the Catholic Church relies heavily on the complementary relationship and the teaching that each sex is imbued with specific God-given traits, to uphold its “sense of order,” not only in the family but across each facet of Catholic life.14

Casti Connubii was widely cited in the postwar years as evidence in support of complementarity in general and Catholic women’s submission to authority specifically. It must be noted that CFM, though quick to support lay autonomy, promoted such ideology into the first half of the 1960s. The April 1959 issue of Act, the CFM newsletter, featured a reprint of a CFM conference address by Fr. Richard Hopkins titled “Role of Husband and Wife.” Hopkins quoted liberally from the sections of Casti Connubii cited above to make his point that if lay Catholics were going to be witnesses to the world they hoped to engage, they needed to do so as the strongest Christian families possible. He described the Christian family as “a mystical body of Christ in miniature. The husband and the father is the head of the body and represents Christ. The wife and mother is the body itself and represents the Church.” Yes, submission can seem off-putting to modern sensibilities, he conceded, but “the old traditional subordination on the part of the wife had its uses . . . in holding the family together.” Hopkins did acknowledge the times, however, advising that “in our present society where women are more highly educated, ordinary prudence would seem to indicate the need of a delicate and tactful exercise of the power of family headship by the husband.”15

The lay editors of Act chose to amplify these remarks by reprinting them. And lest we think this an isolated occurrence, in 1962 a laywoman wrote a piece for Act called “Woman’s Role in Next Year’s Program.” Wanting to contribute, but fearful of women stepping out of the domestic role even in such an action-oriented ministry as CFM, she concluded that “as she is the ‘heart of the home,’ so must the wife seek ways to be the ‘heart’ of the social apostolate.” After all, “if the heart cares, the head will try harder to think of what to do and how to do it.” Although historian Sara Dwyer-McNulty has argued that laywomen did quietly challenge gender norms through lay action in this period, she noted that CFM wives “had to make sure they did not appear as the voice behind the couple—even if they knew that they were.”16

The Cana Movement, administered by clergy but largely staffed by married lay volunteers, did even more to spread the word, enthusiastically, about appropriate gender roles to the young engaged and married couples of the postwar years. Cana facilitators “emphasized a constant review of gender roles that they maintained were ‘natural’ to men and women because many Catholic couples had been ‘infected’ by the secular trends of the day.” In The Basic Cana Manual (1963), used to structure pre-Cana marriage preparation classes, Walter Imbiorski was direct. “Men and women are different,” he wrote. “They are equal in the sight of God, but in marriage they assume different roles, and man in this structured institution is head of woman.”17

It is in this environment that Marriage emerged, and for the first half of the 1960s the magazine largely reflected dominant Catholic teaching on gender roles. One does not have to look hard for these ideas in Marriage. In the seventy-three articles and editorials that discussed gender in the years 1961 through 1966 (after which challenges to these ideas began in earnest), fifty-seven (78 percent) affirmed complementarity and/or gender essentialism. Written by laywomen and laymen, sisters and priests, doctors, theologians, professors, and husbands and wives, they reasserted in a variety of forms what Catholic men and especially Catholic women were to be and do. A smattering of representative articles will show the multitude of ways that readers could encounter the same message in the magazine.

In Casti Connubii, Pius XI elected not to spell out in detail the traits that marked men’s and women’s essential differences, but that did not stop the writers in Marriage, who regularly delineated what it meant in practical terms to be a “complementary” Catholic couple. “Men are more ‘fact-minded,’ whereas women are more ‘intuition-minded,’” G. C. Nabors, MD, claimed in the article “Making Rhythm Work, part I.” “Measuring the body temperature is a fact-finding issue and therefore more easily evaluated by men. The whole idea is so involved with the most delicate of female emotions and intuitions that it is easy to understand why they have difficulty in evaluating the relationship of a temperature graph to the fertile span.” J. Cain, in writing his “Valentine for a Wife,” also expounded on a wife’s limitations: “A wife can be methodical and tidy when it comes to kitchen drawers, but when it comes to reason, her mind is adrift with dreams and tag ends of ideals.” Concurring, Mrs. Robert Jarmusch wrote that suburban couples are balanced since wives focus on “coping with emotions,” while husbands “deal with intangibles and ideas.”18

Clergy also weighed in regularly, throwing the weight of their spiritual and temporal stature behind advice designed to shape intimate relationships and domestic arrangements well outside their personal experience. Aurelius Boberek, OSB, tried to explain “God’s Image in Woman” in 1962, hoping to discourage women from competing with men by praising their most important qualities: “Like God Himself, a woman sees more deeply into the meaning of things, not with the cold calculation of logic but with the wisdom of her heart.” Her vocation “is more in being than in doing. She is not expected to be great. But she is expected to give to man the love, courage, and understanding that inspire him to do great things.” Two months later, the Dominican priest Augustine Rock wrote a lengthy article about the relationship between fathers and daughters. Like Boberek, he concluded that boys are made for doing things in the world, but girls are for love. “He will be proud of her, but a man is more interested in being proud of his sons. His daughters he would rather cherish than be proud of.”19

Women religious appeared far less frequently in the pages of Marriage, surprisingly, since they were such a strong factor in the education of the lay Theresians in the same time period. In the first half of the 1960s they were likely to affirm a traditional view of gender, as in the article “Femininity Can Be Taught,” by Sister Mary Eva, OSB. It described a course on Catholic womanhood taught at Brescia College, a co-ed liberal arts college in Owensboro, Kentucky. According to its designers, “The purpose of this course is to re-emphasize with hardheaded realism the psychological, biological, spiritual and equal (though not identical) role of woman in relation to man in society.” Their curriculum asked, “What is a woman? Why is a woman? And how?” The course was taught in a special pink room with art depicting a woman “kneeling in submissiveness to the Dove, the Holy Spirit, whence flow her virtues, gifts, and fruits. . . . A woman is made to the image of the Holy Spirit of Love. She is made to receive love and to give it back. By using the Gifts of the Holy Spirit, she acquires the Fruits—the gentle, home virtues of charity, joy, peace, patience, long-suffering, modesty, chastity. . . . These help her fulfill the “Why of her existence: A helpmate to man.”20

Authors wrote about every possible trait said to be linked to woman’s nature: submissiveness, receptivity, self-sacrifice, intuition, love, care, generosity, contemplation and mysticism, and above all, motherhood. They wrote with humor, with defensiveness, with patience, and at times with blatant condescension. They chose different characteristics to emphasize but in the first half of the 1960s, few were inclined to challenge the twin ideas that gender was fixed and that men and women were designed, in their natures, to complement each other in their domestic choices, with woman staying at home and man acting as provider. Laywoman Mary Maino spoke for many when she said in 1961, “When God made the two sexes, He made them different in order that they might fulfill their unique roles, and He gave them emotional and intellectual responses to fit them for the role. . . . In either case, personal fulfillment means living according to one’s nature and destiny.”21

Play your role and you will be happy, readers were told, but there were warnings for those who might begin to question. Regular feature writers Richard and Margery Frisbie put readers on notice two months earlier: “The biological and emotional divergences between the sexes are basically unchangeable and no mere alteration of our culture pattern will ever reverse them.” The Frisbies were defensive for good reason, just as Pius XI had been in 1930; they were responding to changing expectations for couples at midcentury—particularly the increasing number of women working outside the home—and they hoped to use Catholic teaching on gender to stop these changes. In the first half of the 1960s, very few challenges to complementarity were mounted in the pages of Marriage, but there are small indicators that the Catholic community, male and female, was preparing to shift its thinking.22

The first of these is a series of articles claiming that gender was more fluid than had been previously admitted. It wasn’t only that these ideas ran in Marriage; they seemed to be particularly supported by the editorial staff. “There is no such thing as a pure male or pure female; we are all mixtures, a polarity of maleness and femaleness,” C. Q. Mattingly, managing editor, proclaimed in a book review in 1965. Moreover, for the 1963 article “The Role of Man and Woman in Marriage,” the editors chose the tagline: “No man is 100% masculine, no woman entirely feminine.” Finally, in 1964 the editors ran two lengthy articles condensed from recent work by the Jesuit theologian Karl Rahner. Near the top of the first article, Rahner states, “Let us first agree that no one sex is better than the other, and no one can possibly act in an exclusively masculine or feminine way as a free person obligated to realize moral values in his or her acts.”

Ultimately, the messages these articles offered were conventional. All three articles undercut their basic premises by continuing to assign specific traits to men and women. In the case of Mattingly, he merely argued that male traits had become too dominant and needed to be balanced by female traits, which men could adopt. The editors negated their tagline in the 1964 article with their own title which allowed only one “role” for the singular man and woman in marriage (even though the article itself was more open to change). And Rahner, after arguing against the rigidity of gender roles, went on to rail against the feminization of the church for eight pages. Nonetheless, these authors were taking a small step toward undermining one of the basic principles of complementarity.23

A pair of articles by Mary Maino from 1961 also illustrate mixed messages on fixed gender roles. Titled “Gifts of the Mind,” and “Getting to Know You,” they offered information and advice to young couples thinking about (and perhaps struggling with) gender role expectations in the early 1960s. The first, while still quite gendered, pointedly notes that women were conditioned to believe they are intuitive, and men were conditioned to be logical. Similarly, college women were taught to use their brains in a logical fashion but were told they were sacrificing their intelligence to become housewives, and it became a self-fulfilling prophecy. Marriage requires intelligence, she argued, and not any special female intelligence either. “In marriage, particularly, men and women need to see one another not as men or as women but as persons,” she wrote, “made by God with an intellect that hungers after the things that are of God.” But her second article demonstrates how confusing it was to read Marriage on gender in the early 1960s. Just after declaring that couples should view each other as individual people, ungendered, her second piece delineated the traits of male and female and the importance of Catholic women staying within their natural role.24

Lastly, a handful of articles in the first half of the decade represent a more familiar indicator of discontent about the implications of fixed gender roles: the cry of the unhappy Catholic housewife. The most well-known of this genre is “Happy Little Wives and Mothers,” a moving piece by Katherine Byrne that appeared in the influential Catholic weekly magazine America in 1956. In that same vein came “The Motherhood Wilderness” (1961) and “Prayers for the Reluctant Housewife” (1966), the authors of which ultimately acknowledged the rightness of Catholic housewifery but spent the majority of their column inches venting their myriad frustrations and revealing their sadness.

Robin Worthington recommended that housewives know what type of prayer will work best for them, because they would not survive housewifery without it. If the prayer begins with asking God to make you perky and cheerful and you can’t stomach it, move on, she advised. If it starts, “The next hour or two is going to be perfectly vile,” that’s the prayer for you. “Let’s say you’re a Reluctant Housewife,” she wrote. “Full or part time housewife. Full or part time reluctant (we all have our days). We won’t go into why you’re reluctant. You’ve met theories enough already. The psalmist summed up the classic reason centuries ago: Lord, ‘I am shut in. I cannot escape.’” Anne Topatimlis’s “The Motherhood Wilderness” was an epic recitation of her daily ordeals, ending with a plea that Byrne and Worthington would recognize: “When these pressures reach their boiling point comes the cry ‘I’ve got to get out of here! . . . [but] we cannot go, whether we want to or not.”25

The year 1967 marks a change in Marriage on questions of complementarity and laywomen’s gender identity. Of the 106 articles and editorials in the study published between 1967 and 1975 (whose primary or secondary purpose was to discuss gender), 62 affirmed traditional roles (58 percent—a drop from 78 percent in the first half of the 1960s). What happens, then, is clearly not a sudden shift to feminism if the majority of articles still supported the status quo. Yet something definitely changed in these years, as more and more writers felt welcome, or encouraged, or emboldened enough to challenge what had for so long been seen as the only way to be a Catholic woman in a Catholic marriage.

What we have in Marriage is a gradual opening to new ways of thinking that manifested in a number of debates about key issues that played out over the course of years. While the editorial staff could weigh in on these issues in ways both heavy-handed and subtle, they were usually content to allow opposing voices to be heard. This approach gave laywomen the chance to speak frankly on the questions that concerned them about the most intimate aspects of their lives. The remainder of this chapter explores a handful of these debates from the second half of the 1960s through the mid-1970s, each of which demonstrates the boundaries imposed on laywomen’s intimate lives through the restriction of gender identity, and the language some Catholics—women and men—were developing to lift them.

Let’s begin with the question of what writers at the time termed “sex-role stereotyping.” The affirmative case in the debate over this question, basically essentialism, has already been outlined, but what of the other side? By the midpoint of the 1960s, Catholic laywomen had had ample exposure in the national media to criticism of female essentialism, not only through the publication of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique (which was widely reviewed, if skeptically, in Catholic periodicals, including Marriage) but also through other available feminist writings and coverage of the growing movement. What’s more, educated and active Catholic laywomen would also likely have been aware of debates over women’s equality that had begun to creep into Catholic circles through the Catholic feminist movement, then in its first phase. We know that any reader of Marriage who was also active in her NCCW affiliate would have been exposed to such ideas through the NCCW’s national publications. The question was whether anyone would speak up in this forum, which was male-dominated and dedicated to strengthening Catholic couples. The answer is yes, and it is in this debate that laywomen’s voices begin to emerge in revealing ways.

“I’m a housewife (or should I say homemaker) and mother of four, and I am tired of hearing of the glories of motherhood. ‘Motherhood’—that golden word that is supposed to make us glow. . . . I’m one of those mothers that just doesn’t ‘glow.’ Biologically, I’m a mother, but psychologically I might have been better fitted at anything else.” Marge Morton did not glow, and she did not care who knew it. Similarly, Lucille Harper told a story of a friend whom she considered very “sacrificial,” and it worried her. “She wants to excel as a woman, and to be considered feminine, which in her mind means to give beyond endurance. . . . Giving to the point of exhaustion isn’t feminine, it’s life-shortening.” Here were two laywomen willing to state boldly, without qualifiers, what to this point was taboo: “natural” traits were anything but, and they could lead to psychological and physical harm for the Catholic women who attempted to conform to them.26

Perhaps for these reasons, and a host of others, it became increasingly normal to hear laywomen call for an end to sex-role stereotyping in the pages of Marriage. For instance, early Catholic feminist and philosopher Rosemary Lauer took aim at those who believed that a college education was wasted on Catholic wives because they would never use it in their role as mothers. “First of all,” she began, “such a viewpoint presupposes that a woman can attain the complete development of her personality simply by being a wife and mother—a conviction that made sense only as long as theology professors could teach with a straight face the Aristotelian doctrine that ‘men attain their perfection by developing their intellects; women attain theirs by bearing children.’” When she was finished with the theologians, she targeted another venerable institution a little closer to home for Marriage: “One hopes that it will filter through to the Cana conferences too and that all the unscientific nonsense about woman’s ‘intuitional’ approach to reality as opposed to man’s ‘rational’ approach will be consigned to the limbo it deserves.”27

It is no coincidence, I think, that all three of these laywomen authors—Marge Morton, Lucille Harper, and Rosemary Lauer—appeared in the “Speak Up” section, a column reserved for extended reader commentary. Readers could submit an essay on any topic for potential publication in the magazine. Highly skilled laywomen writers were often featured in this section, and they tended to gravitate toward gender themes. I suspect this was one means by which the editors attempted to balance their tendency to select male authors in greater numbers as experts who earned full articles. Still, the essays they published are invaluable in a study attempting to reclaim the voices of laywomen, and one imagines the opportunity to have their say was more significant to them than the twenty-five dollars the women received in compensation.

Another Catholic feminist, Sidney Callahan, the author of the first Catholic feminist monograph, The Illusion of Eve, was invited to write for Marriage in 1965. She took the opportunity to weigh in on the debate over essentialism in what was for Marriage an extremely lengthy article as the Council was drawing to a close. “Those Council Fathers who wished more encouragement and recognition for women would do well to approve a strong declaration of married women’s equality,” she wrote. “But let the masculine half of the Church be wary of stating that women have ‘special talents’ (even as a tactic in their defense).” Offering Marriage’s female readers a new kind of vocabulary to critique what their church had taught them, Callahan pointed out “everyone should recall that part of the oppression borne by every minority group has been the dominant majority’s insistence upon rigid definitions and distinctions.”28

Sidney Callahan, perceived as a moderate insider in the intellectual lay Catholic community (her husband, Daniel Callahan, was the author of the widely read The Mind of the Catholic Layman) had the standing to get away with such a statement, but she was not the only one allowed to speak her mind in this forum. As we shall see, one of the places where laywomen spoke most freely about their own self-conceptions as Catholic women was in the “Reader Reaction” section, where people in this community could exchange ideas and debate questions of importance to them. The issue of essentialism was no exception. After a particularly conservative article on gender roles appeared, Kathleen Kinahan from Illinois wrote, “I think most women are sick and tired of being dissected in print, and are proceeding to ‘do their own thing’ as they see right. And certainly, many, if not most, women are going to turn off the opinions of a middle-aged marriage counselor (male) who wants women to stay in their place. . . . Women are human beings—they will no longer conform to one stereotyped image—please, accept us as ourselves, and drop the subject.” In response to another such article, a pair of college seniors wanted it known that “not all females walking this earth feel a need to achieve self-identity through having children.” Finally, Lucille Martin of New Jersey likely spoke for many when she requested “an editorial policy that refuses to accept for publication articles that encourage readers to be men and women first, and persons second.” No such policy seems to have been adopted.29

Such questioning of complementarity and gender essentialism had real world implications for the laywomen who participated in it. Identity was more than how women viewed themselves; an ideological change in this area could potentially transform their marriages. To see how, let us return briefly to the Cana movement. Cana conferences and literature insisted “that fathers were the head and mothers the heart of each family, and remind[ed] participants that masculine aggressiveness and feminine docility formed the bedrock on which a successful marriage was constructed.” In fact, the group that now influenced much of the premarital formation for Catholic couples in the United States went so far as to claim “that marriages often failed because men and women did not accept the innate qualities of their nature.” The rightness of male headship was also reinforced in popular devotions of the day.30

The conversation that took place in Marriage over male headship in the Catholic family—really an extension of the discussions of essentialism—is one of the most surprising findings to emerge from this research. Unlike talk of women’s place in the church, which frequently arose in the laywomen’s organizations, the sensitive subject of power and submission in laywomen’s domestic arrangements simply did not arise in their official outlets. However, the editors of Marriage wanted to open the floor for discussion of this aspect of Catholic marital relationships. The fact that such a conversation took place at all worked to undermine strict adherence to the principles of complementarity since it questioned beliefs at the foundations of the teaching.

The challenge to headship mounted in Marriage was not an inevitable response to feminist ideas entering the popular discourse in this period. Two other religious communities of the same era demonstrate that a reinforcement of headship was a popular response to feminism as well as an entry into conservative political activism. Many American evangelicals, for example, espoused male headship and female submission as markers of their Christian identity well after American Catholics ceased to proclaim them as central to their religious self-perception. R. Marie Griffith’s study of evangelical women in the 1970s, particularly as revealed through their confessional stories in the magazine Aglow, shows that the women often promoted their own submission to male headship as a means of fixing troubled marriages and bringing the men in their lives to salvation. Furthermore, she finds the idea that only through submission will women find true freedom to be prominent. Neither idea emerges as significant in Marriage. The trends are markedly different as well; Griffith’s findings show commitment to male headship on the increase through the 1970s, whereas it is clearly on the decline among the Catholics writing in Marriage. Julie Debra Neuffer also chronicles similar ideas that emerged in Mormonism in the early 1960s and spread to millions through the publication of Helen Andelin’s Fascinating Womanhood (1963). Andelin argued that a potent combination of obedience and femininity would save American marriages. “Don’t change your husband,” she urged. “Change yourself.”31

In the early 1960s, similar concerns about male headship began to appear in the magazine; as early as 1961, Marriage expressed its fears about men losing their authority in the family. Such worries, and accompanying defensiveness, often arose in the “Family Front” column, a regular feature written until 1965 by Richard and Margery Frisbie. Strongly antifeminist, the Frisbies were enthusiastic and frequent champions of complementarity in the first half of the 1960s. They assured readers in 1961, despite reports to the contrary, that “researchers found no evidence of the supposed decline in male status. . . . He still makes many of the final decisions and performs traditional male duties while his wife tends the house and children. The new element perhaps is how he achieves his position. ‘He must prove his right to power, or win power by virtue of his own skills and accomplishments in competition with his wife.’”32

So committed were the Frisbies that, when in 1964 the Belgian cardinal Leo Jozef Suenens—well-known in that moment for advocating for women at the Council—spoke in Chicago, they asked him point-blank how he reconciled his views on women’s rights with biblical calls for wives’ submission. He answered that wives were like the Council fathers who submitted to papal authority, but “when you say ‘let bishops be subject to the Pope’ that doesn’t mean there’s no collegiality.’” The Frisbies reported he said this “with a twinkle in the archepiscopal eye,” and they “were charmed by the image of the family as a miniature Council over which the Holy Spirit hovers while husband and wife pray and ponder over their decisions.” His answer was perfect for the Frisbies because it suggested that traditional gender roles could fit into the plan of the dynamic, modern church.33

Female authors routinely supported male headship against a culture all too ready to let it go. Louise Shanahan pointed out that gender roles were in flux in 1962, and lamented that “in far too many homes there has been a shift from the emphasis on the husband as head to a two-headed idea of husband and wife sharing equal powers.” She explained that the shift was “related to . . . the stress on personal fulfillment and happiness as a major goal in marriage,” perhaps inadvertently implying that submitting to headship was not a pleasant experience for women. While Shanahan wanted women to understand that happiness should not even be their chief goal, other writers assured women that submission to male headship was the only means of achieving marital happiness. In “My Husband the Boss,” Alice Waters advised women not to bolt if their husbands laid down the law: “No, girls . . . Remember, you’ll have no neuroses, or psychoses—if you let husbands take charge, everything comes up roses!” A reader offered the ultimate reason for submission. “We obey our husbands,” she wrote, “not because of what they ask but because we do love God above all.”34

Perhaps in response to the growing backlash against male headship in the larger culture, other authors recommended that men demonstrate their authority through their role as fathers even more than as husbands. In the article “Why Is a Father,” dads were advised to take control of potty-training “since the father represents authority to the child.” The physician author argued, “It is important that the head of the family help his child make this first harsh adjustment to the demands of civilization for social conformity.” Similarly, a 1964 article titled “Examination of Conscience for Family Men” recommended for the daily examen the questions “Do I recognize that I am each child’s first vision of authority and consequently I am a symbol of God to my youngsters?” and “Do I act fully in accord with the precept that I am the head and my wife is the heart of our home?”35

The editorial staff of Marriage certainly seemed to believe in male headship in the early 1960s and frequently used their editorials to promote this view. A 1962 editorial complaining that not enough husbands read the magazine (a not infrequent lament by the editors) explicitly referred to men as head of the house; a 1964 editorial about wedding announcements noted that the groom did not appear: “Now, if the husband is really ‘head of the wife,’ as Scripture puts it, then why not show the head in the picture too?” These casual references, together with the proheadship “Family Front” column, and the frequency of other articles in support, suggest general agreement on the subject.36

However, something odd occurred in November 1964 when managing editor C. Q. Mattingly wrote the magazine’s first pro–women’s rights editorial. It contained an explicit statement against women’s submission to male headship: “It is annoying for women to hear and read . . . that the family and community are in such a sad state because women will not let their husbands be head of the family.” Citing the first creation story in Genesis, he coupled this statement with a salvo against complementarity, arguing that woman was “equal and of the same nature as man, not an inferior, and not set apart for ‘separate’ treatment.”37

What are we to make of such a bold statement against headship, though, when a second editorial appeared in August of the following year that once again explicitly affirmed headship, this time from the associate editor Mary Alice Zarella? In an appropriate marriage, guided by the tenets of complementarity, “The woman is not a pale reflection of the male,” she wrote. “As a wife she becomes more womanly. The husband becomes more manly. Deliberately they differentiate to achieve perfection.” Furthermore, “the wife is not resentful of her husband’s authority. Becoming complementary partners is a challenging and lifelong vocation.” The about face may reflect a split on the editorial board, but the more likely immediate cause was fear over circulation. In the same issue as the editorial in November 1964, the editors placed a mildly feminist piece by Ann Ward titled “What Do Women Really Want?” The article provoked a flood of letters that the editors summarized for the February 1965 issue as overwhelmingly negative. The editors would not publish a pro–women’s rights editorial again until 1975.38

Yet from 1966 on, the number of articles that called for an end to male headship outnumbered those in support. While the editors would not speak explicitly against headship again, and they continued to run pieces in support of complementarity, they provided myriad opportunities for those “annoyed” women, as well as sympathetic men, to speak for themselves. The magazine became a space where the Catholic community could think out the implications of male headship for Catholic couples, and contemplate alternatives. As a result, the magazine ceased to present a united front on the teachings of complementarity.

A good indicator that the editors had become more open-minded is the June 1969 issue, which contained opposing articles on headship, published on consecutive pages without editorial comment. The first appeared in the “Family Front” column from a female author, and asked (in honor of Father’s Day) whether “young people today would find it easier to accept the authority of their parents and others placed over them if they had the example of wives accepting the authority of their husbands? Would men approach marriage differently if they realized that as the head of the family they were responsible to God for those under their care?” The article in response, from a male author, pointedly asked very different questions: “What is a man? What is a father? . . . Quick-and-easy traditional answers are as useless as physiological ones, e.g.: ‘The father is the head and the mother is the heart of the good Christian family.’ It means everything, means nothing, and is an insult to women. So we back up and observe again.” Moreover, an article on sexual freedom in the following issue called “efforts to restore male dominance” both “reactionary” and “unrealistic.” This male author claimed that “the insights provided by modern psychological knowledge support an equalitarian relationship between sexes rather than a dominant-subordinate one.”39

Marriage’s practice of featuring opposing opinions is best seen in the work of one contributor, the Catholic journalist and freelancer Louise Shanahan. Shanahan came out staunchly against egalitarian marriage in an article in 1962, but when her next articles on gender roles began to appear in the second half of the 1960s, she seemed willing to explore new ideas. It is worth looking in depth at her output because the editors returned to her again and again for her particular brand of article, an interview with experts in response to an important gender question of the day. At twelve articles, Shanahan is the largest single contributor in the sample.

It can be difficult to know what Shanahan herself believed because the majority of her articles quoted extensively from the chosen expert, and her framing of the articles always suggested that she concurred with whatever the expert said. As a result, her pieces could be wildly contradictory. In the eleven articles that Shanahan published in Marriage between 1966 and 1971, she managed to both affirm essentialism and proclaim it outdated, write with alarm about women’s liberation and promote women’s empowerment, warn of the impending disintegration of marriage as an institution and argue that marriage was actually in good shape after all.

The closest she came to endorsing egalitarian marriage outright is in the 1971 article “The Changing Husband Image,” in which she interviewed five young couples about authority in marriage. Shanahan opened the article by asking, “Have the current trends articulated by women’s lib groups caused unusual stress, fear, or anger on the part of the husband?” She concluded, however, that “all is not ominous and grim” and went on to quote a number of husbands who not only accepted shared authority with their wives, but embraced it. Said one young husband, “For all the nonsense of the extremists in women’s lib, I think they are on the right track when they want to push women into other experiences out of the home. . . . I feel I am a much more flexible husband than my father was. Marriage a generation ago was considerably more rigid. The husband could be a tyrant and get away with it. Today that is out of the question.” A young wife concurred: “The husband today is no longer lord and master. It is much healthier for the marriage, and it doesn’t take away a jot from his manhood.”40

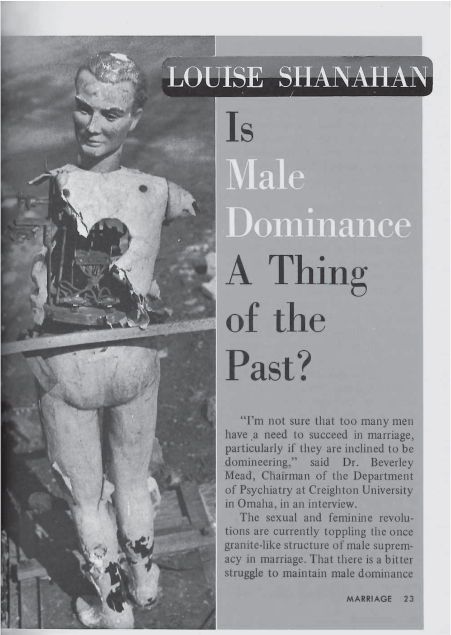

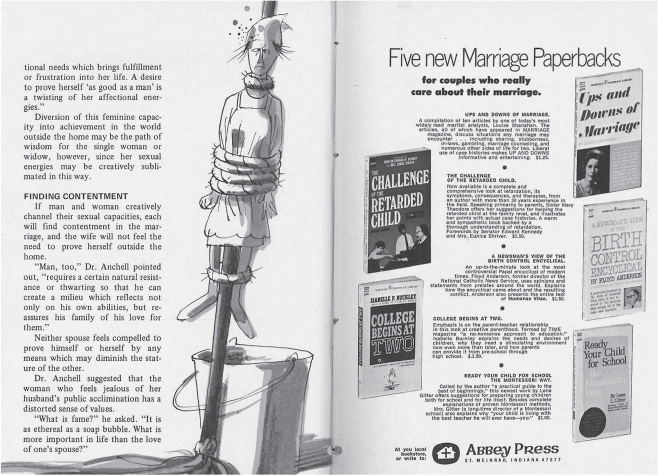

The illustration for this Louise Shanahan article in Marriage (1970) conveys brokenness, male fragility, and profound confusion about changing gender roles.

(Courtesy of St. Meinrad Archabbey)

But Shanahan also gave equal time to the couples who preferred headship as a model, and noted men’s increasing discomfort with egalitarian marriage and its effect on their gender identity. “My biggest complaint about women is that they have become obnoxiously aggressive,” one husband remarked. “I think I’m like other men my age. I feel as if we are trapped in Unisexville.” Shanahan also recognized that men might miss the right of command under the new model of marriage. “If there is an occasional ache in his heart when he remembers his father’s thundering commands and a subsequent instant feminine response,” she noted, “the neuter-generation husband may find compensations in the vast array of the means of self-expression available to him that were absent in his father’s day.” Yet she hardly saw this as a positive development. You could cut her sarcasm with a knife: “He may, if he feels like it, treat himself to one of those marvelous perfumed preparations that now take the place of less imaginative aftershave lotions. No longer is it a woman’s prerogative to go out and splurge on a hat or cologne if she is feeling depressed.”41

Despite these references to disgruntled husbands, frustration for women was a much more common theme in Shanahan’s work. Not a feminist herself, Louise Shanahan rarely advocated directly for women’s liberation (and in fact she took multiple swipes at the movement), but she often put forward the idea that women were limited and frustrated in marriages where they were controlled by their husbands. In “Money: His and Hers” (1966), for example, she interviewed several women who described how much they hated having no financial say in the household. Those who wrested back that power (and it was described as an abuse of power on the husbands’ part) were clear about what it gave them. One noted that when she had some financial control she was “not merely someone’s wife or mother or laundry service. I’m me. And it’s a good feeling.” Shanahan also wrote a very practical piece for wives in 1971 called “Marriage: Act of Negotiating.” The tagline asked, “Why do women accept a second-rate marriage relationship?” Shanahan’s chosen expert answered that women viewed themselves as subordinate because they had been conditioned by their husbands to see themselves that way. The rest of the article offered concrete techniques for women desiring to assert authority in their own marriages. “Practice with a friend,” Shanahan recommended. Don’t get emotional and “stay with the facts.”42

Even Shanahan’s most antifeminist and essentialist articles hinted at her awareness of women’s struggles. An example is the astonishing “Are You Planning to Run Away?” (1971), in which she featured a female private detective who told wives enamored of feminism to rethink their plans of escape, to stay with their abusive or cheating husbands, and to consider if their own nagging didn’t contribute to the problem. Yet in this same article she named women’s deep well of frustration as the fuel that fed the women’s movement in the United States. “Women’s liberation is rocking the boat for women who have been smoldering for years,” she admitted. In the previous year she wrote, “It is evident that those taking up the cudgels for the feminine revolution are expressing the frustrated feelings of women everywhere.” Here was an author who, without embracing feminism, could give female readers permission to feel angry about their lot as wives under the burdens of headship.43

But, unlike Shanahan, many of the voices in Marriage on the question of headship were unequivocal. Once again, we can look to the letters to the editor for strong statements by women on practical questions of identity. “A single authority figure is outmoded,” Mrs. Carroll A. Thomas wrote, and “[I] hope our little girl and her brothers will grow to fully respect themselves and others as human beings, with responsibilities to themselves and to others.” Suzanne L. Bacznak was in an egalitarian marriage and could confirm that it worked: “When my husband and I married we accepted the concept that two equal beings were joined together of their own free wills, each fully accepting the other.” As so many letter writers did, Bacznak turned to the concrete rather than the theoretical: “On matters affecting the whole family we both talk over the decision to be made and discuss it fully until both agree. . . . In actual practice is this not what most happily married couples do? Work together. Why not realize this fact and accept it?”44

Other women commissioned to write for the magazine noted the ongoing shift toward equal partnership and wrote approvingly of it. In 1967, Iris Rabasca noted that the threadbare advice (head/heart) that mothers had long given to their engaged daughters would not do, as “many of today’s young wives will no longer accept this ‘sure cure’ for a happy marriage, a bitter pill, too difficult to swallow.” Such “compact clichés,” as Rabasca labeled them, “seem to undermine [women’s] individuality, their personalities, and their status within society, as well as within their marriage.” Kathryn Clarenbach went even further that same year, claiming that abandoning headship would do more than just make women happier and more fulfilled: “I maintain that true partnership of husband and wife in the home will do more to strengthen family life in America than anything else.”45

Equally common was the suggestion that men abused their power, or had the potential to do so; egalitarian marriage was promoted explicitly as a means of protecting women from abuse. Gloria Skurzynski laid the groundwork with “History’s Woman Haters,” a 1971 article detailing husbands’ abysmal treatment of their wives in the medieval period. The editors tried to soft-pedal the article with its tagline (“If you think women are getting the medieval treatment, then you had better re-check your history”), and the author agreed that it was not accurate to call today’s antifeminists “medieval” (“thank God!”). Yet Skurzynski wrote this piece for a reason, as a reminder perhaps of what wives could experience at men’s hands when male authority went unchecked. In such circumstances, women were most valued for their youth and beauty, could not control access to their bodies, and were confined to the home, she reminded Marriage readers.46

Readers also heard in 1970 that “the male need to dominate is frequently at the root of much marital misery,” and in 1971 that wives were “no longer merely chattels” of their “dominant and domineering” husbands. Women paid a mental price when men abused their authority, writers claimed. One author noted “the dreadful damage done to women’s psyches” by the tradition of headship. Another lamented the women who were at the mercy of their husbands’ “moods and whims.” A third described how women were encouraged to suppress their true personalities to be the wives that traditional husbands favored. “Brenda, don’t be too aggressive,” one woman reported being told by her parents, “because no man will love you.” Finally, the 1969 Louise Shanahan article “The Tyranny of Love” took this to its ultimate end by describing an abusive marriage where the husband became “more and more domineering, ruthlessly disregarding her wishes with veiled threats about his masculine superiority.” The wife could only ask herself, “Is it like this in other homes? Are wives who are doormats happy? Are women who attempt to live with their husbands as equals miserable?”47

Ultimately, as in “The Tyranny of Love,” Marriage was much more inclined to pose questions than it was to provide definitive answers, but this is precisely what makes the magazine so remarkable in the context of the Catholic media in the 1960s: the answer to every question posed about intimate relationships was not complementarity. Marriage was willing to give women a voice in a wide-open debate over questions of authority, power, and submission in their own homes. While the editors rarely advocated for change in these matters themselves, they created a space where women could express a variety of opinions and advocate for themselves if they chose, or simply learn of alternatives to the way of life they had been conditioned to believe was natural and expected.

An even greater preoccupation in the magazine was the debate over working wives, a consistent theme throughout the years of this study. Unlike the articles on essentialism and headship, the conversation over whether Catholic wives should work outside the home was almost exclusively conducted by women writers. Presumably women believed this topic fell squarely within their expertise and area of concern. Of the many objections raised against working wives in Marriage, most were representative of mainstream ideas, although writers could couch their arguments in Catholic terms. The precepts of complementarity were certainly raised, as were notions of prayerful housewifery meant to convey the deep spiritual importance of women’s work in the home. The women who defended work outside the home mostly stuck with debunking myths and airing their frustrations over being judged neglectful and unwomanly. Their commentary on the debate as a whole hints at the editors’ desire to move the conversation forward past the condemnation of women who dared take on paid employment. Toward the 1970s we begin to see a truly feminist perspective on the issue emerge in Marriage, largely couched in terms of the need for women’s personal fulfillment.48

It’s hardly surprising that the subject of working wives appeared with such frequency given the inordinate amount of attention paid to women’s steady transition into the workforce after World War II. Commentators were responding to very real trends. Between 1940 and 1960, there was a 400 percent increase in the number of working mothers. In the 1960s alone, the number of women in the workforce increased from 23 million to over 31 million. The incessant attempt to normalize domesticity and the open hostility expressed toward women in the workplace in the same thirty-year period may be read as a defensive posture against demographic trends very much in evidence in writers’ social networks and neighborhoods as well as in the statistics trotted out on every suitable occasion.49

Articles opposed to wives working seemed almost unavoidable in Marriage in the 1960s, their authors ready to throw every possible argument at a woman tempted to leave her kitchen. First, authors created the impression that the desire to work outside the home was abnormal. “Men love work but women love men,” the Frisbies asserted, describing the correct order of things in 1961. Another writer claimed that “there is a tremendous emphasis on the importance of careers for woman, but I am afraid that our mature woman cannot get terribly excited about the subject.” Housewives themselves supported these claims with articles like “I Enjoy Being a Housewife!” and “I Don’t Want to Be Free.”50

Advocates of housewifery argued that duty must be held above a woman’s need for fulfillment outside the home. “This affluent American society has created many false images,” Mary Ann Black said, “among them the damaging contention that women are entitled to freedom, freedom from the drudgeries of housework, freedom from the responsibilities of motherhood and freedom to be herself first and a wife second.” Referring to “fulfillment propaganda,” writers regularly blamed feminism for encouraging women to neglect their homes in search of self through paid employment, even though the increase in working wives predated second-wave feminism.51 As one letter writer put it in 1971, “Let Betty Friedan play up my hidden potentialities that I’m supposed to be wasting on my spouse, three children and my home. As long as I have a chance left, and I still do, I’ll remain a slave to a mannish man, three cherubs and a demanding home. Me, I am a slave; but I am free. I have love!”52

In any case, women were unlikely to find outside work worthwhile, they were told. Most jobs available to women were boring and tedious (not unlike housework), far from the exciting careers for women spotlighted in the media. And if a woman made more money than her husband she would need to counteract it at home so she did not undercut her man. One such woman described the balancing act of maintaining her husband’s authority when her salary was higher: “At home our children know who’s boss, even in the little things. For instance, I always make sure my husband is served first at mealtime and has a chance at the biggest pork chop—or whatever.” Was the “fulfillment” that came from working really worth it?53

Readers were also informed that working wives were both selfish and neglectful of their homes and families. “It is supremely undesirable that a married woman should take up gainful employment only for the sake of getting more out of life,” one author said, “for then the family will suffer from her selfishness.” A 1971 article purporting to help women decide whether or not to send their young children to day care in actuality heaped accusations of neglect upon working moms. For instance, the author claimed that children in day care “were unable to relate to overtures of love,” and that full-time childcare “was often the pivotal factor in the case of a mentally disturbed child.”54

Of course, authors also invested much energy in extolling the vital and intrinsic contributions of wives and mothers, relying heavily on the rhetoric of Catholic essentialism and complementarity. The editors could assist with this as well, as in 1961 when they prominently displayed a quote from Pope Pius XII in a section called “Think It Over”: “Now the sphere of woman, her manner of life, her native bent, is motherhood. . . . For this purpose the Creator organized the whole characteristic make-up of woman, her organic construction, but even more her spirit, and above all her delicate sensitiveness. Thus it is that a woman who is a real woman can see all the problems of human life only in the perspective of the family.” Catholic women had a sacred mission beyond the day-to-day work of the home that could not be disrupted by the siren song of the modern world. “The real job of a mother is to raise saints,” as a reader reminded everyone in 1962.55

Authors did acknowledge with regularity that housewifery was difficult, as we have already seen, but unlike the “cries of the unhappy housewife” mentioned earlier, most articles kept an upbeat tone and sought solutions in keeping with the rightness of Catholic women’s role as the heart of the home. For a period of time in the mid-1960s, writers in Marriage were particularly fascinated by the ideas of the Catholic writer Solange Hertz, the author of Women, Words, and Wisdom (1959).

Hertz’s work appeared multiple times, excerpted at length as well as mentioned in other people’s articles. Margery and Richard Frisbie described her philosophy for readers in “Family Front” in 1964. First, Hertz believed that housewifery was a vocation, and that it was “universal” for women. As such, she “consider[ed] all the current talk about women developing themselves outside the home ‘tiresome.’” The heart of her writing, though, was the belief that a wife’s work in the home should be treated as a call to the contemplative life.56

In 1965, the editors excerpted Hertz’s book under the title “Meditations while Mopping the Floor.” The chosen passages encouraged women to think of themselves as prayerful monastics as they went about their repetitive chores. Quite down to earth, Hertz did not pretend that housework was pleasant, but she did argue that it could be valuable if considered in the proper terms. Among other ideas, her theology promoted the idea that through the physical acts of housewifery—that is, through suffering—women helped redeem the sin of the world for which womankind was largely responsible: “Dirty dishes, dirty diapers, dusty floors, unwashed bodies . . . are quite simply effects of Eve’s fall and must be accepted as such. In these physical aspects God keeps before our eyes the hideousness of sin. Leaving aside its obvious value as a penance, our battle against dirt, our repugnance for it, is a symbolic battle against sin. . . . It’s the housewife’s special little share in the Redemption to be able to atone for others’ sins by washing others’ clothes.” Hertz and others like her used Marriage to encourage housewives and mothers to give their work meaning, and to prove—definitively, they thought—that Catholic wives did not belong in the workplace.57

But another set of articles existed alongside these works battling the trends of American culture. In 1962 Marriage published its first article in support of wives working, if only part-time. The author, Eleanor Culhane, made no radical arguments, but her piece is revealing for what it says about the debate itself. When the topic arose, she said, “the quiet game of bridge may erupt into a roaring volcano of emotion as partners divide and slams go unbid.” Everyone had an opinion on what was incontrovertible: wives were going to work in ever-larger numbers, and not for the reasons everyone supposed, either. “For extra income, for an extra adult interest in life, for a welcome change from unrelieved domesticity which may actually enable her to be a better wife and a more patient mother,” not to earn money for an extra television set. Nor, she added, were the children of these “frivolous” mothers out wandering the streets. Culhane neatly shows us what Catholic working women had to contend with in the 1960s.58

One woman who wrote of having to work by necessity spoke of being “condemned to death” for it, made to “bear the brunt of sarcasm and degrading remarks.” Antoinette Bosco added that these women haven’t “been proven guilty of anything, only accused,” and that the debate over their choices had generated “more heat than light.”59

A series of writers sought to shine that light by explaining what they believed to be misunderstandings about working wives. In the mid-1960s these most often included the idea that women worked to buy luxuries, a common theme in the history of opposition to working women and a preoccupation in a Catholic community concerned about materialism and secularization. More than one woman shared her personal experience to show that this was false, but it was left to the 1967 article “Women as Second Class Citizens” to state the obvious. Katheryn Clarenbach argued that the question “Should women work?” was “foolish” when you considered the number of women in poverty. “Women in the United States have always shared economic responsibility,” she pointed out to this largely middle-class readership. Contributors also insisted that working women did not neglect their children; even the editors made the argument in 1964 that women were not “abandoning children and home just to make a fast buck ‘out in the world.’” Besides, Bosco reminded readers, a Catholic wife who was unhappy at home was equally capable of messing up her kids: “Staying at home out of a sense of fortitude, martyrdom, or guilt does not communicate healthy emotional growth in her children.”60

In the latter half of the 1960s and early 1970s writers in favor shifted away from a defensive posture to offer more expansive reasons for wives to work outside the home, reasons clearly influenced by the women’s liberation movement. The most common theme offered was indeed personal fulfillment. One of the first articles to offer this view was “The New Woman,” a piece written by a religious feminist in 1968. She noted that women do not make plans for themselves, in fact they balk at doing so. In consequence, “many women, even today find that they are not capable of thinking much beyond the age of forty or forty-five when all the children have left home. That this is so is an unparalleled waste and a great tragedy.” She went on to warn that “intentionality alone can save us from drifting or floating to a premature form of living death where we find all our desires for personal satisfaction and fulfillment are empty and pointless.” Another author argued that “because today’s college-educated woman is trained for mobility and freedom, she cannot be eternally denied these things without dire consequences.”61

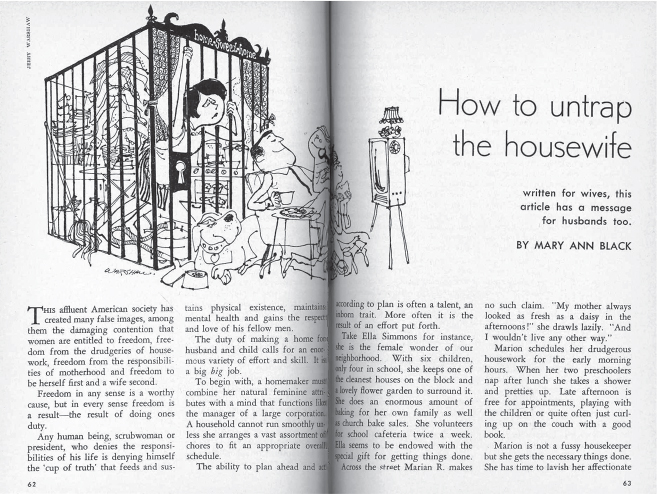

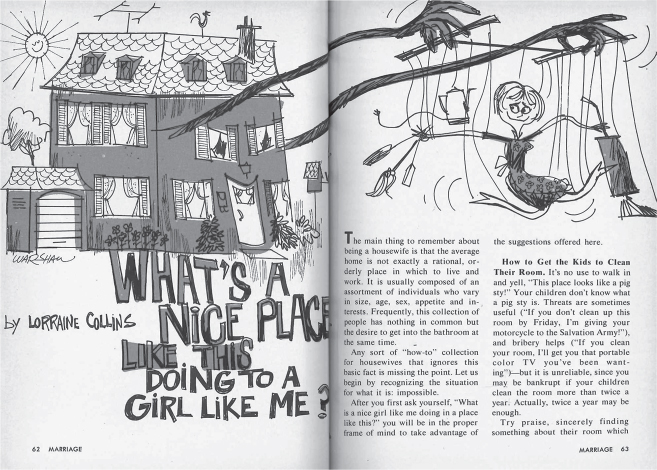

Curiously, Marriage’s editors reinforced the idea that women needed freedom to find fulfillment, but the editors did so in articles that supported the gender status quo. On three separate occasions they chose to accompany essentialist articles with illustrations depicting housewives bound, caged, or otherwise trapped by housewifery. The traditional “How to Untrap the Housewife” (1967) featured an aproned woman in a cage staring longingly at her family (including the dog) watching television. In a similar vein, “What’s a Nice Place Like This Doing to a Girl Like Me?” (1973) showed a woman in an apron strung up like a marionette with her own house maniacally pulling the strings. Most disturbingly, Louise Shanahan’s reactionary “Woman 1970: A Counsellor’s View” featured a drawing of a woman in kerchief and apron (naturally) bound by rope to a broom at neck, torso, and ankles and suspended over her own mop bucket. Marriage might continue to offer a voice to those who believed in complementarity, but the editors regularly found ways to raise the idea that women needed more for their well-being than what the church had been willing to offer them. The implicit became explicit in January 1973 when the priest John Catoir mused on “The Future of Christian Marriage.” Speaking specifically of women he urged, “Marriage should not engulf people, should not trap them into a narrow space in which they have no possibilities of growth.” Catoir knew of what he spoke: he was identified as chief judge of the marriage tribunal in Paterson, New Jersey.62