3

Pugilism and Style

All the great poets should have been fighters. Take Keats and Shelley,

for an example. They were pretty good poets, but they died young.

You know why? Because they didn’t train.

Cassius Clay, 19641

Byron consistently affected hauteur about those who took writing too seriously; a gesture characteristic of what Christopher Ricks terms his ‘flippant lordliness’.2 In an 1821 journal entry, he noted that his mother, Madame de Staël and the Edinburgh Review had all, at various times, compared him to Rousseau. A page then follows in which he explains why he cannot see ‘any point of resemblance’. There are many points of contrast, and some interestingly odd conjunctions. The first comes in Byron’s initial distinction – ‘he wrote prose, I verse; he was of the people, I the Aristocracy’. Prose then is aligned with ‘the people’; poetry with the Aristocracy. The revelation that ‘he liked Botany, I like flowers, and herbs, and trees, but know nothing of their pedigrees’ further damns prose for its utilitarianism. Rousseau is little more than an Enlightenment taxonomist. From then on, it is a short step (a mere colon) from ‘He wrote with hesitation and care, I with rapidity and rarely with pains’ to an account of what ‘better’ things an aristocrat might find to do:

He could never ride nor swim ‘nor was cunning of the fence’, I am an excellent swimmer, a decent though not at all dashing rider . . . sufficient of fence . . . not a bad boxer when I could keep my temper, which was difficult, but which I strove to do ever since I knocked down Mr Purling and put his knee-pad out (with the gloves on) in Angelo’s and Jackson’s rooms in 1806 during the sparring . . .

In a journal entry of 1813, written before going to dinner at Tom Cribb’s with Jackson, Byron complained that ‘the mighty stir made about scribbling and scribes’ was a ‘sign of effeminacy, degeneracy and weakness. Who would write, who had anything better to do?’3

Byron’s concern with class is evident in the scorn he expressed five years later for Leigh Hunt’s reference to poetry as a ‘profession’: ‘I thought that Poetry was an art, or an attribute, and not a profession.’4 There was one profession, however, which Byron admired unreservedly. Pugilism was an activity in which the boundaries between professional and amateur were clear. Nonchalance was not therefore required, and proper training was desirable. Byron could train as hard as he liked to box, without anyone suspecting that he was not a gentleman. And even he thought that there were literary activities which required a comparable professional attitude. In ‘Hints from Horace’ (1811), Byron lambasted the Edinburgh Review critic Francis Jeffrey as unqualified to discuss his poems, suggesting that no boxer would presume to enter the ring without proper training.5

In this chapter, I shall explore some of the ways in which, during the early decades of the nineteenth century, writers and artists found in pugilism not only a subject-matter, but the basis for a method.

LITERARY FLASH

Writing about pugilism reached its zenith in the 1820s, at a time when the sport itself had begun to wane. At the forefront of the fad was undoubtedly Pierce Egan’s Boxiana; or Sketches of Ancient and Modern Pugilism. The first volume appeared in 1812, followed by a second in 1818, a third in 1821, and a new series in two volumes in 1828 and 1829. His round-by-round accounts of fights between Mendoza and Humphries, or Cribb and Molineaux, are still the major sources quoted today. In 1824, he began editing a weekly paper, Pierce Egan’s Life in London and Sporting Guide, which later developed into the famous sporting journal, Bell’s Life in London. What distinguished Egan’s work from other boxing histories of the period (such as William Oxberry’s 1812 Pancratia) was its great verve and distinctive style. Dubbed ‘the Great Lexicographer of the Fancy’, Egan did not just reflect the language of the Fancy, he created it.6 His 1822 edition of Francis Grose’s Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue included many of his own coinings.

Egan’s writing is characterized by a lively mixture of elaborate metaphors, dreadful puns and awful verse. In this passage from ‘The Fancy on the Road to Moulsey Hurst’, aided by a lavish supply of commas, italics and capitals, he describes a particular type of ‘fancier’:

His heart is up to his mouth every moment for fear he should be floored, he is anxious to look like a SWELL, if ’tis only for a day: he has therefore borrowed a prad to come it strong, without recollecting, that to be a top-of-the-tree buck requires something more than the furnishing hand of a tailor, or the assistance of the groom. It should also be remembered, that although the CORINTHIAN at times descend hastily down a few steps, to take a peep into the lower regions of society, to mark their habits and customs, yet many of them can as hastily regain their eminency, as the player throws off his dress, and appear in reality – a GENTLEMAN.7

The horseman’s flash style is an unsuccessful attempt at assuming a higher class position – his gig is ‘hired’, his horse (‘prad’) borrowed, and his clothes reflect the taste of his tailor. The enterprise is doomed, Egan suggests; it is obvious to anyone really flash, really knowing, that he is an impostor, an ‘EMPTY BOUNCE’. The CORINTHIAN ’s ‘mark[ing]’ of ‘the habits and customs’ of a lower class is not, however, subject to the same disparagement. He does not cling to his disguise, but readily, ‘hastily’, throws it off to resume his status. Slumming is temporary and permissible while social climbing, which strives for permanent change, is not.

Class mobility was a key element in the spread of boxing and its idiom during this period. The early nineteenth century saw the establishment of numerous magazines, many of which catered for a growing ‘army of bachelor clerks and lawyer’s apprentices’ whose aspiration to gentility often manifested itself as an interest in traditionally aristocratic pastimes.8 Flash slang involved the middle-class imitation of an upper-class imitation of lower-class idioms.9

The Tory Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine was particularly keen on traditional squirish activities such as pugilism and published numerous reports, stories and articles on the sport. (In 1822 it declared itself ‘a real Magazine of mirth, misanthropy, wit, wisdom, folly, fiction, fun, festivity, theology, bruising and thingumbob’.10 ) Most notable were the boxing writings of John Wilson, Professor of Moral Philosophy at Edinburgh University, writing as Blackwood’s fictional editor, ‘Christopher North’. Wilson had boxed while a student at Oxford – his friend Thomas De Quincey recalled that ‘not a man, who could either ‘give’ or ‘take’, but boasted to have punished, or to have been punished by, Wilson of Mallens [Magdalen]’ – and often depicted himself in Blackwood’s as a kind of critical pugilist.11 But while Hugh MacDiarmid later wrote scathingly of Wilson as ‘the most extraordinary exponent’ of the kind of ‘verbiage’ which is intended ‘simply to batter the hearer into a pulpy state of vague acquiescence’, others relished both the verbiage and the battering.12 ‘I cannot express . . . the heavenliness of associations connected with such articles as Professor Wilson’s,’ wrote Branwell Brontë in 1835, ‘read and re-read while a little child, with all their poetry of language and divine flights into that visionary realm of imagination’.13

One of Wilson’s finest flights of imagination can be found in the May 1820 issue of Blackwood’s in the form of a ‘“Luctus” on the Death of Sir Daniel Donnelly, Late Champion of Ireland.’ The prize-fighter had died after a particularly heavy drinking session. Wilson included copiously footnoted tributes from imagined scholars in Greek, Hebrew and Latin, along with poems in the style of Byron and Wordsworth. While Byron is perhaps too obvious a target, and ‘Child Daniel’ not particularly funny, the ‘extract from my great auto-biographical poem’ contributed by W. W. is sharply attentive to both the Lake Poet’s style and his distance from the world (and slang) of the Fancy:

Albeit, who never ‘ruffian’d’ in the ring,

Nor know of ‘challenge’, save the echoing hills;

Nor ‘fibbing’, save that poesy doth feign,

Nor heard his fame, but as the mutterings

Of clouds contentious on Helvellyn’s side,

Distant, yet deep, aguise a strange regret,

And mourn Donnelly – Honourable Sir Daniel: – 14

Wordsworth enjoyed a rare immunity to ‘boximania’.15 By the 1820s, it had become almost unthinkable in certain circles not to understand boxing slang or the ‘flash’. The OED cites the first instance of ‘flash’ being used to mean ‘dashing, ostentatious, swaggering, “swell”’ in 1785: the slightly later meaning of ‘belonging to, connected with, or resembling, the class of sporting men, esp. the patrons of the ring’ dates from 1808. But the two meanings seem related. ‘A flash man upon the town’ is surely swaggering and dandyish, as well as knowledgeable about prize-fighting. A third, related, meaning is ‘knowing, wide-awake, “smart”, “fly”’. Egan opens Boxiana with a footnote explaining the Fancy ‘as many of our readers may not be flash to the above term’. But it seems likely, as Egan must surely have realized, that if a reader was flash to ‘flash’, he would be flash to ‘the Fancy’.16

Keats’s description of Byron’s Don Juan as ‘a flash poem’ seems to draw on all these meanings; few poems are so knowing, swaggering, and connected to practitioners and patrons of the ring.17 Canto XI presents an encounter between Juan, newly arrived in London from Spain, and an assailant called Tom, ‘full flash, all fancy’, whom Juan shoots and kills. ‘O Jack, I’m floor’d’ are his final words. Byron then devotes a stanza to the memory of Tom, ‘so prime, so swell, so nutty, and so knowing’. Tom would have understood such flash language, but Juan does not even understand standard English.18 A note is supplied, which refuses to explain anything because, Byron says, ‘the advance of science and of language has rendered it unnecessary to translate the above good and true English, spoken in its original purity by the select mobility and their patrons’. He directs any readers who ‘require a traduction’ to Gentleman Jackson.19 In 1808, John Cam Hobhouse commented that his friend had been ‘deeply admitted into the penetralia Jacksoniana’; some years later, in his Life of Lord Byron, Thomas Moore recalled his amusement at observing ‘how perfectly familiar with the annals of “The Ring”, and with all the most recondite phraseology of “the Fancy”, was the sublime poet of Childe Harold’.20 (Byron’s attachment to boxing and its language was, Moore felt, one of his several ‘boyish tastes’.)

Gary Dyer argues that Byron and his friends were attracted to the Fancy’s dialect because it ‘was fashioned to hide meanings from outsiders’.21 Indeed as Thomas Moore put it in the preface to his satirical poem ‘Tom Crib’s Memorial to Congress’, flash ‘was invented, and is still used, like the cipher of the diplomatists, for purposes of secrecy’.22 What that secrecy meant to upper-class ‘fanciers’ like Byron is a matter for speculation. Dyer reads Byron’s secrets as always ultimately referring back to sodomy. Byron’s biographer, Benita Eissler, maintains that Jackson and Angelo were ‘rumoured’ to be lovers as well as business partners, and that the Academy served as a cover for illicit meetings.23 While there is no direct evidence for this, it is certainly true that Byron’s London circle was interested in sodomy as well as in boxing.

But a secret language surely holds other attractions. One is exclusivity, or, in the age of the beginnings of commercial journalism, the pretence of exclusivity. In the course of a general denunciation of the Fives Court as a ‘college of scoundrelism’ in 1824, Washington Irving’s Buckthorne asks, ‘what is the slang language of “The Fancy” but a jargon by which fools and knaves commune and understand each other, and enjoy a kind of superiority over the uninitiated?’24 Robert Southey’s fictional Don Espriella, ‘writing to the uninitiated’ back in Spain in 1807, certainly takes great pleasure in explaining such terms as ‘bottom’, ‘a pleasant fighter’ and ‘much punished’.25 In 1818, however, phrases such as these remain untranslated by Byron, although he tells us that only what he calls ‘the select mobility and their patrons’ will understand; only they speak ‘good and true English’. Byron’s play on ‘select nobility’ does more than suggest that boxers are like noblemen. His footnote also mocks the widespread tendency to explain flash language in footnotes. By freely coining his own new phrase, ‘select mobility’, Byron is attacking jargon’s claim to provide unique access to knowledge.

Many other poets made comparable play with boxing language. The narrator of Henry Luttrell’s Advice to Julia: A Letter in Rhyme (1820) stops a perfectly adequate description of a fight to apologise for his lack of pugilistic vocabulary:

But hold. – Such prowess to describe

Asks all the jargon of the tribe;

And though enough to serve my turn

From ‘Boxiana’ I might learn,

Or borrow from an ampler store

In the bright page of Thomas Moore . . .26

Thomas Moore is an interesting choice of source, for he much disliked boxing. Nevertheless, Moore too sought out the company of Jackson, and once attended a fight (which was ‘altogether not so horrid as I expected’) for the sake of his verse; in order ‘to pick up as much of the flash from authority, as possible’.27 Although he ‘got very little out of Jackson’, he went on to write two popular poems on pugilistic themes.

John Hamilton Reynolds, on the other hand, loved boxing (he was the boxing correspondent, as well as theatre critic, for the London Magazine). As a young man he regularly attended fights and sparred, while writing poetry and working as a clerk in an insurance office. The Fancy (1820) is semi-autobiography disguised as the fictional biography of Peter Corcoran, boxing groupie and ‘Student of Law’ (the name was borrowed from an eighteenth-century fighter and had the advantage of sharing an acronym with the Pugilistic Club). Corcoran is also a poet, and much of The Fancy consists of his poems: ‘pugilism’, the editor notes, ‘engrossed nearly all his thoughts, and coloured all his writings’. The writing is full of cringeworthy pugilistic puns. Consider, for example, one of the ‘Stanzas to Kate, On Appearing Before Her After a Casual “Turn Up”’:

You know I love sparring and poesy, Kate,

And scarcely care whether I’m hit at, or kiss’d; –

You know that Spring equally makes me elate,

With the blow of a flower, and the blow of a fist.

‘Spring’ is asterisked, and the fictional editor writes, ‘I am not sure whether Mr. Corcoran alluded here to the season, or the pugilist of this name.’28

Such pompous comments work to distance the reader from the editor as well as from Corcoran. In the preface, for example, he notes that ‘this style of writing is not good – it is too broken, irresolute, and rugged; and it is too anxious in its search after smart expressions to be continuous or elevated in its substance’.29 By the book’s end, we become aware both of the compulsive appeal of such ‘rugged’ and punning language – particularly as a way of deflating the ‘elevated’ discourse of much poetry; again Wordsworth seems a target here – and of its repetitive limitations.

A wider look at the literature of the 1820s (in particular magazine literature) shows just how pervasive an addiction to flash really was. Thomas De Quincey, for example, savoured its use in a variety of contexts, some of which were more apposite than others. Boxing slang works particularly well in a July 1828 attack on ‘The Pretensions of Phrenology’, because both boxing and phrenology are interested in the human skull. Medical and sporting jargon are set against each other in a description of the phrenologists who, ‘after receiving a few hard thumps on the frontal sinus and the cerebellum, . . . were fain to have recourse to shifting and shuffling; bobbing aside their brain-boxes’. In the debate De Quincey champions the philosopher Sir William Hamilton, who we soon learn is no ‘shy fighter’, no ‘flincher’, a ‘tolerably hard hitter’ and ‘rather an ugly customer’: ‘the chanceried nobs of his two antagonists exhibit indisputable proofs of his pugilistic prowess, and of the punishment he is capable of administering’. And this is only the opening paragraph.30

Later that same month, De Quincey became a co-editor of the Edinburgh Evening Post, contributing the latest news from London and writing many short editorial notices. One addressed a dispute between two Edinburgh intellectuals on the teaching of Greek at Scottish universities with the promise of organizing ‘a set-to . . . in our Publishing Office, between three and four’ on any day of their choosing.31 De Quincey and his co-editor, the Reverend Andrew Crichton, did not get on, and Crichton’s own articles often contained digs at De Quincey’s ‘addiction’ to metaphors drawn from the ‘vile’ sport of boxing. The ‘defence of . . . pugilism’ is ‘very shallow’, and ‘monstrously inconsistent with Christian principles’, he wrote in a review of Blackwood’s; an author who resorts to ‘the slang of the fancy’ has ‘a rough lump of the brute in him, which ought to be cut out by the scalpel’.32 The surgical metaphor is itself an implicit rebuke to such authors.

‘HARD WORDS AND HARD BLOWS’ IN HAZLITT

In essays on topics ranging from parliamentary debate to sculpture to theatre to boxing, William Hazlitt talked about blows. The Reformation struck a ‘deathblow’ at ‘scarlet vice and bloated hypocrisy’; William Godwin’s Enquiry concerning Political Justice dealt a ‘blow to the philosophical mind of the country’; Wordsworth’s ‘popular, inartificial style gets rid (at a blow) of . . . all the high places of poetry.’33 ‘On Shakespeare and Milton’ (1818) reads like a comparison of the styles of two boxers rather than two writers. Shakespeare’s blows are ‘rapid and devious’, ‘the stroke like the lightning’s, is sure as it is sudden’. Milton, on the other hand, ‘always labours, and almost always succeeds’.34 ‘Milton has great gusto. He repeats his blow twice; grapples with and exhausts his subject.’35

And it is not only poems which deal blows. In an 1826 essay ‘On the Prose-Style of Poets’, Hazlitt asserts categorically that ‘every word should be a blow: every thought should instantly grapple with its fellow’. ‘Weight’, ‘precision’ and ‘contact’ are needed to strike the best blow, and produce the best prose. Some writers display some of these virtues; few all. Byron’s prose, for example, is ‘heavy, laboured and coarse: he tries to knock some one down with the buttend of every line’.36

Hazlitt foregrounds the relationship between fighting and writing styles in an 1821 essay on William Cobbett. The essay begins by comparing the radical politician to the boxer Tom Cribb. Initially the comparison seems to be based on the fact of Cobbett’s devotion to pugilism and his self-representation as, like Cribb, a living embodiment of John Bull.37 Hazlitt then moves on to matters of style:

His blows are as hard, and he himself is impenetrable. One has no notion of him as making use of a fine pen, but a great mutton-fist; his style stuns his readers, and he ‘fillips the ear of the public with a three-man beetle’.38

The last phrase is a quotation from Henry IV part 2, and its inclusion, alongside sporting analogy, is a favourite technique of Hazlitt’s. In the pages that follow, the metaphor is developed more fully. Cobbett has a ‘pugnacious disposition, that must have an antagonist power to contend with’, but this is a ‘bad propensity’ since:

If his blows were straightforward and steadily directed to the same object, no unpopular Minister could live before him; instead of which he lays about right and left, impartially and remorselessly, makes a clear stage, has all the ring to himself, and then runs out of it when he should stand his ground.39

The essay concludes by shifting the comparison. Cobbett is now no longer England’s hero, Tom Cribb, but ‘Big Ben’, Benjamin Brain, known to be ‘bullying and cowardly’. Not so tall but very stocky, Brain had defeated the long-reigning champion Tom Johnson in 1791 in ‘a most tremendous battle’.40 Johnson had been a favourite of the fashionable Fancy, and was even reputed to have worn pink laces in his boxing boots.41 Big Ben was less gentlemanly. He badly damaged Johnson’s nose in the second round, and fought on regardless, even when, in his distress, Johnson soon after broke a finger on a ring post. For many commentators this victory marks the end of the first era of British boxing, when men stood toe-to-toe and punched away without much technique. For Hazlitt to compare Cobbett to Big Ben is to insult not just his bravery, but also his skill and intelligence. Cobbett, he concludes, is ‘a Big Ben in politics, who will fall upon others and crush them by his weight, but is not prepared for resistance, and is soon staggered by a few smart blows’.42

Hazlitt’s most sustained comparison of fighting and writing can be found in ‘Jack Tars’, an essay originally published in 1826 under the title ‘English and Foreign Manners’. ‘There are two things that an Englishman understands,’ Hazlitt begins, ‘hard words and hard blows,’ and he goes on to define the English character in terms of a sort of aggressive empiricism. French audiences appreciate Racine and Molière, whose ‘dramatic dialogue is frothy verbiage’; English audiences prefer to watch boxing, where ‘every Englishman feels his power to give and take blows increased by sympathy’, or, what is put forward as its equivalent, English plays whose dialogue ‘constantly clings to the concrete and has a purchase upon matter’. Englishmen, in short, perceive the world through violent opposition. This makes them feel ‘alive’ and also manly. ‘The English are not a nation of women . . . it cannot be denied they are a pugnacious set.’43

A complex alignment of qualities is being made. Some are familiar – pugnacity, masculinity and Englishness; new to the mix is empiricism, defined as the pugnacious, masculine, English way of perceiving the world. The English ‘require the heavy, hard, and tangible only, something for them to grapple with and resist, to try their strength and their unimpressibility upon’.44 English empiricism is, in Hazlitt’s terms, less concerned with what John Locke called secondary qualities (colour, taste and smell are, Hazlitt maintained, of more interest to the French), than ‘the heavy, hard and tangible’ primary qualities.45 The solid materialism of Englishness (‘our lumpish clay’) is a favourite theme of Hazlitt’s, especially in opposition to light French liveliness. English criticism of French culture is difficult, he argued, because ‘the strength of the blow is always defeated by the very insignificance and want of resistance in the object’.46

‘The same images and trains of thought stick by me’, Hazlitt wrote in his ‘Farewell to Essay-Writing’ (1828).47 This is clearly true, but his use of boxing idiom and metaphor was not an unthinking tick. Indeed, it serves much more various and complex purposes in his work than it does in that of any other writer of the time. Contemporary discussions of Hazlitt’s language, however, rarely went beyond politically motivated condemnation or praise. Blackwood’s argued that prize-fighters were ‘downright Tories’ and therefore belonged in Blackwood’s, but other journals were more interested in suggesting that neither Hazlitt or pugilists were suitable for their polite middle-class readers. The New Edinburgh Review was ‘sorry to say’ that some of Hazlitt’s allusions were ‘of the lowest and most shockingly indelicate description’. It joined the Quarterly Review in dismissing him as a ‘Slang-Whanger’:

We utterly loathe him where he seems most at home, namely, among pugilists, and wagerers, and professional tennis-players, passing current their vain glorious slang. We protest against allusions to the very existence of the Bens and Bills and Jacks and Jems and Joes of ‘the ring’, in any printed page above the destination of the ale-bench; but to have their nauseous vocabulary defiling the language of a printed book, regularly entered at Stationers’ Hall, and destined for the use of men and women of education, taste, and delicacy, is quite past endurance . . . we strenuously protest against this bang up style, this ‘fancy diction’, in a series of ‘original essays’. Our conclusion, at least, is irresistible, – the author has not kept good company . . .48

The anti-Cockney snobbery of the Tory journals would not have surprised Hazlitt, nor would the qualified support of John Hamilton Reynolds, author of The Fancy, and boxing correspondent of the liberal London Magazine. Indeed Reynolds’s only criticism of the second volume of Table Talk – that Hazlitt’s points are put forward too directly – is itself made in ‘fancy diction’:

The style of this book is singularly nervous [i.e. sinewy, strong and vigorous] and direct, and seems to aim at mastering its subject by dint of mere hard hitting. There is no such thing as manoeuvring for a blow. The language strikes out, and if the intention is not fulfilled, the blow is repeated until the subject falls.49

Fascinated by boxing’s metaphorical possibilities, Hazlitt wrote only one essay on the thing itself, ‘The Fight’ (1822). One of the most influential and frequently anthologized pieces on boxing, the essay encompasses many of the themes already discussed – style, Englishness, masculinity, the material world – and presents them in a manner at once casual and densely considered.

Consider the epigraph, which rewrites Hamlet’s musings on what he hopes to accomplish by putting on a play for Claudius’s benefit (or punishment):

— The fight, the fight’s the thing,

Wherein I’ll catch the conscience of the king.50

Hazlitt’s substitution of ‘fight’ for ‘play’ has two implications: first, that a fight is a play, a kind of performance; secondly, that this particular fight/play is a performance from which something is to be learnt. Hamlet’s play will catch the king’s conscience. What about the fight Hazlitt witnesses? The contest is first of all a contest of performed styles; styles that we have come to think of as French and English. The champion, Bill Hickman, the Gasman, is ‘light, vigorous, elastic’, his skin glistening in the sun ‘like a panther’s hide’; his unfavoured challenger, Bill Neate, is ‘great, heavy, clumsy’, with long arms ‘like two sledge-hammers’. At one point, ‘Neate seemed like a lifeless lump of flesh and bone, round which the Gasman’s blows played with the rapidity of electricity or lightning.’ The two men also differ in personality. Hickman is a Homeric boaster, who arrives to fight ‘like the cock-of-the-walk’. Hazlitt is more judgmental than Homer, however, and complains that Hickman ‘strutted about more than became a hero’. Neate is modest and celebrates his eventual victory ‘without any appearance of arrogance’.

In general, though, both men wonderfully exemplify courage and endurance. But of what kind? Classical comparison casts Neate as Ajax to Hickman’s Diomed, Hector to his Achilles. The fight itself amply confirms the ‘high and heroic state of man’. It reminds Hazlitt of the ‘dark encounter’ between clouds over the Caspian, in Milton’s Paradise Lost, as Satan faces Sin and Death at hell’s gates.51 And yet the life actually lived during a fight is nasty, brutish, and (relatively) short. The fighter’s triumph is not only transitory, but in essence banal (‘The eyes were filled with blood, the nose streamed blood, the mouth gaped blood’), and invariably surreptitious (like a 1990s rave, the fight between Hickman and Neate took place, at the shortest possible notice, in a field near Newbury). Could it be that the literary form best suited to this brief battle was not epic poetry, but the essay?

Hazlitt’s essay, like the preparations made for the fight by participants and spectators alike, is much ado, if not exactly about nothing, then about something as fleeting as it is pungent. He finds it difficult enough to get himself out of London. Missing the mail coach prompts a self-reproach that seems excessive, ‘I had missed it as I missed everything else, by my own absurdity.’ Finally, however, he is on his way, and as he puts on a great coat, his mood improves. Leaving London behind, he enters another world with its own distinctive rules and customs. Joe Toms walks up Chancery Lane ‘with that quick jerk and impatient stride which distinguishes a lover of the FANCY’; in the coach to the fight Hazlitt meets a man ‘whose costume bespoke him one of the FANCY’; on the way back he describes his friend, Pigott, as being ‘dressed in character for the occasion, or like one of the FANCY; that is, with a double portion of great coats, clogs, and overhauls’. It is only on the journey home that Hazlitt himself is properly ‘dressed in character’; Pigott supplies him with a ‘genteel drab great coat and green silk handkerchief (which I must say became me exceedingly).’ The costume gives him the confidence to deride a group of ‘Goths and Vandals . . . not real flash-men, but interlopers, noisy pretenders, butchers from Tothillfields, brokers from Whitechapel’ who brashly interrupt a discussion of the respective merits of roasted fowl and mutton-chops. The essay ends with him reluctantly returning these clothes. So far, so Pierce Egan.

Like Egan, Hazlitt relished flash language. ‘The Fight’ is littered with italicized idioms: ‘turn-up’, ‘swells’, ‘the scratch’, ‘pluck’. But the great literary virtue of an essay is that it does not have to stick to one kind of performance. Hazlitt rapidly expands his repertoire of allusion beyond Homer, Shakespeare, and Milton. His allusions politicize pugilism. They enhance its democratic credentials. Riding in the coach with Toms, he recites, ‘in an involuntary fit of enthusiasm’, some lines of Spenser on delight and liberty; Toms promptly translates these ‘into the vulgate’ as meaning ‘Going to see a fight’. The connection between boxing, sentiment and (political as well as psychological) liberty is reinforced on the return journey, when Pigott reads out passages from Rousseau’s New Eloise. And if literature can enhance an appreciation of boxing, boxing also has literary potential. Hazlitt is enchanted by the conversation of a man he meets in the pub, and tells him that he talks as well as Cobbett writes. Perhaps in response to his critics, Hazlitt makes it clear that sporting interests are not the preserve of Tory squires; middle-class radicals can make them urban, modern and sophisticated.

Hazlitt’s pleasure in joining this convivial, masculine world is palpable. This had been his first fight, he announces at the beginning of the essay, ‘yet it more than answered my expectations’. But what were those expectations? In ‘On Going A Journey’, published four months earlier, Hazlitt had written of the desire to ‘forget the town and all that is in it’. In the town was his landlady’s daughter, Sarah Walker, whose charms and unfaithfulness form the subject of an autobiographical meditation, Liber Amoris (1823). She is never mentioned here, but Hazlitt does occasionally (and rather cryptically) evoke his misery. The essay begins by dedicating what follows to ‘Ladies’. He compliments ‘the fairest of the fair’ and the ‘loveliest of the lovely’ and entreats them to ‘notice the exploits of the brave’. But a rather sour note emerges when he urges ladies to consider ‘how many more ye kill with poison baits than ever fell in the ring’. These words gain a poignant resonance when we consider that an early draft of the essay contained a passage about his lovelorn wretchedness. David Bromwich argues that an awareness of this passage reveals ‘the under-plot’ of the essay and explains its ‘impetuous pace’ and ‘arbitrary high spirits’.52

‘The Fight’ tells the story of a man who is almost successful at escaping himself. If romance is a ‘hysterica passio’, the Fancy is ‘the most practical of all things’, and its emphasis on mundane facts – its thoroughly English empiricism – distracts him most of the time.53 ‘The FANCY are not men of imagination’, he is pleased to note. Occasionally, though, he slips back into self-pity. After describing the pleasures of the training regime, he cannot help adding:

‘Is this life not more sweet than mine?’ I was going to say; but I will not libel any life by comparing it to mine, which is (at the date these presents) bitter as coloquintida and the dregs of aconitum!

But such passages of lovesick rhetoric (passages common in Liber Amoris) are infrequent. As long as he can talk of boxing and mutton-chops, love and London can be kept at bay:

A stranger takes his hue and character from the time and place. He is a part of the furniture and costume of an inn . . . I associate nothing with my travelling companion but present objects and passing events. In his ignorance of me and my affairs, I in a manner forget myself.54

Hazlitt’s language of the blow provided him with a means to compare poets and politicians to athletes and (democratically) to judge one against the other.55 The ‘blows’ of John Cavanagh, the fives-player, for example, were ‘not undecided and ineffectual’, unlike Coleridge’s ‘wavering’ prose.56 Hazlitt also judged his own work by the standard of sport, and sometimes found it lacking. ‘What is there that I can do as well as this?’ he once asked on observing some Indian jugglers. ‘Nothing’, was his reply. ‘I have always had this feeling of the inefficacy and slow progress of intellectual compared to mechanical excellence, and it has always made me somewhat dissatisfied.’57 ‘I have a much greater ambition to be the best racket-player, than the best prose-writer of the age.’58 But most of the time, Hazlitt did believe that prose could eventually achieve its own excellence, comparable (among other things) to relation between parts in the Elgin marbles; ‘one part being given, another cannot be otherwise than it.’59 ‘The Fight’ ends with a ‘P.S.’, in which Hazlitt agrees with his friend Toms’s description of the fight as ‘a complete thing’. The last sentence – ‘I hope he will relish my account of it’ – suggests that the essay is consciously striving to be something equally ‘complete’, something in which all the parts harmoniously create a whole (however ephemeral).

SCULPTING AND PAINTING THE BOXERS

In the same month that ‘The Fight’ appeared, Hazlitt published the first of three essays on the Elgin Marbles. His remarks there, and elsewhere, directly attack Sir Joshua Reynolds’s Discourses (1769–1790), which argued that the beauty of a work of art was ‘general and intellectual’: ‘the sight never beheld it, nor has the hand expressed it: it is an idea residing in the breast of the artist’.60 On this view, the artist is completely divorced from the craftsman who works with his eyes, hands and materials. Hazlitt, on the other hand, emphasized the ways in which art resembled craft and sport – and in all these spheres genius could emerge. One of the pleasures of painting, he maintained, was that, unlike writing, it ‘exercises the body’ and requires ‘a continued and steady exertion of muscular power’. The best paintings, and sculptures, were those in which the muscular power of both sitter and artist remain apparent. The Elgin Marbles ‘do not seem to be the outer surface of a hard and immovable block of marble, but to be actuated by an internal machinery’; in Hogarth’s pictures, ‘every feature and muscle is put into full play.’ Both are ‘the reverse of still life’; both are comparable to the ‘harmonious, flowing, varied prose’ of the essayist.61

Hazlitt frequently included Hogarth in his pantheon of English geniuses, all of whom rejected notions of the ideal in order to grapple with matter as it is and who defined beauty in democratic and empirical terms. ‘The eye alone must determine us in our choice of what is most pleasing to itself,’ Hogarth wrote in The Analysis of Beauty (1753), and in that choice, sports fans have at least as good an eye as sculptors or anatomists:

Almost everyone is farther advanced in the knowledge of this speculative part of proportion that he imagines; especially he hath been interested in the success of them; and the better he is acquainted with the nature of the exercise itself, still the better the judge he becomes of the figure that is to perform it.

In terms that would be echoed in the twentieth century by Bertolt Brecht and Ezra Pound, Hogarth argued against aesthetic contemplation as a disinterested activity. The more interested the spectator is (by which he presumably means the more money he has wagered) the better his judgment is.

For this reason, no sooner are two boxers stript to fight, but even a butcher, thus skill’d, shews himself a considerable critic in proportion; and on this sort of judgment often gives, or takes the odds, at bare sight only of the combatants. I have heard a blacksmith harangue like an anatomist, or sculptor, on the beauty of a boxer’s figure, tho’ not perhaps in the same terms . . .

Too many contemporary artists, Hogarth maintained, learn about the human body by looking at sculpture (particularly classical sculpture) rather than by looking at people.

I firmly believe, that one of our common proficients in the athletic art, would be able to instruct and direct the best sculptor living, (who hath not seen, or is wholly ignorant of this exercise) in what would give the statue of an English-boxer, a much better proportion, as to character, than is to be seen, even in the famous group of antique boxers, (or as some call them, Roman wrestlers) so much admired to this day.62

Hogarth is referring to a sculpture, now knows as ‘The Wrestlers’, which was much praised and studied by the English Academicians, and formed the basis for an extensive discussion of muscles in both Joshua Reynolds’s Tenth Discourse (1780) and John Flaxman’s Lectures on Sculpture (1829).63 Small bronze copies were widely disseminated.64 In order to understand and thus represent human movement, Flaxman argued, the sculptor must understand anatomy, geometry and mechanics:

The forced action of the boxers renders the muscular configuration of their shoulders so different in appearance from moderate action and states of rest, that we derive a double advantage from the anatomical consideration of their forms: first, we shall learn the cause of each particular form, and, secondly, we shall be convinced how rationally and justly the ancients copied nature.65

Hogarth, meanwhile, had looked to Figg, Broughton and George Taylor as his models. Two years before writing the Analysis, he had produced a series of drawings of the dying Taylor (supposedly intended for his tombstone), including Death giving George Taylor a Cross-Buttock and George Taylor Breaking the Ribs of Death (illus. 20). But it was Figg (‘more of a slaughterer than . . . a neat, finished pugilist’) who especially appealed to Hogarth, not only as an exemplar of English vigour and honesty, but also as a fellow modern urban professional.66 Figg appeared in several of Hogarth’s satirical paintings and prints: in Southwark Fair (1732) he sits grimly upon a blind horse in the right-hand corner, in A Midnight Modern Conversation (1733) he is sprawled drunkenly in the foreground, and in plate two of The Rake’s Progress (1735), ‘Surrounded by Artists and Professors’, he is pushed into the background by a dandyish French fencing master.67

|

20 William Hogarth, George Taylor’s Epitaph: George Taylor Breaking the Ribs of Death, pen and ink over pencil and chalk, c. 1750. |

Fifty years on, boxing was much more respectable than it had been in Hogarth’s day, and Hazlitt noted approvingly that the actor Edmund Kean was not ashamed to admit to ‘borrow[ing] . . . from the last efforts of Painter in his fight with Oliver’ in his portrayal of Richard III’s final moments.68 Next door to the Fives Court, retired prize-fighter Bill Richmond ran the Horse and Dolphin, a pub where he was said to have initiated the fashion of sparring bare-chested in order that spectators could admire the muscular development of the fighters. Various members of the nearby Royal Academy, including Benjamin Haydon and the President, Joseph Farington, frequented the Fives Court and Horse and Dolphin, but more often the boxers posed at the Academy’s life classes.69 Farington’s diary for 19 June 1808 records a visit to the home of his friend Dr Anthony Carlisle, soon to be elected Professor of Anatomy at the Royal Academy, where the company were presented with ‘Gregson, the Pugilist, stripped naked to be exhibited to us on acct. of the fineness of His form.’ Farington’s approach is not that of Hogarth, or Hazlitt. The real is only interesting in its relation to the ideal. Gregson the pugilist quickly becomes Gregson the anatomical specimen, the classical approximation:

All admired the beauty of His proportions from the Knee or rather from the waist upwards, including His arms, & small head. The Bone of His leg West Sd [side] is too short & His toes are not long enough & there is something of heaviness abt the thighs – Knees & legs, – but on the whole He was allowed to be the finest figure the persons present had seen. He was placed in many attitudes.70

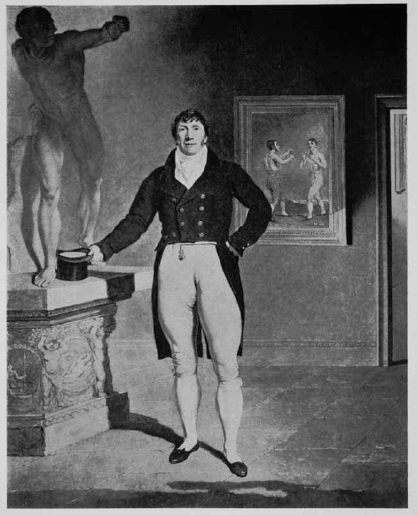

While Hogarth was always concerned about proportion in relation to function (‘fitness’) – what ‘dimensions of muscle are proper (according to the principle of the steelyard) to move such or such a length of arm with this or that degree of swiftness of force’ – the Academicians had very little interest in the use of the bones and muscles they were contemplating.71 Boxers were to be admired to the extent that their bodies approximated pre-determined ideals of beauty, not because they worked well. Ben Marshall’s portrait of Jackson, copied as a mezzotint by Charles Turner in 1810, positions the clothed prize-fighter beside a classical sculpture. We cannot help comparing their legs (illus. 21).

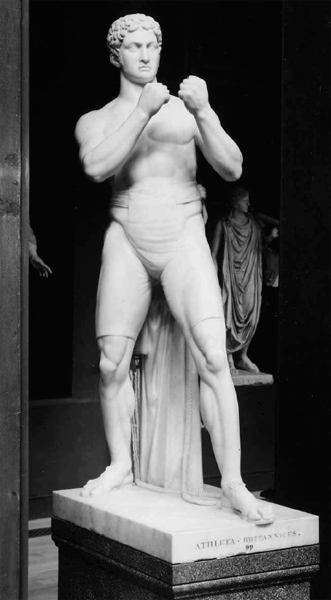

Ten days after Farington first saw Gregson, the party reassembled at Lord Elgin’s house to see him ‘naked among the Antique figures’, the newly arrived fragments of the Panthenon frieze now known as the Elgin Marbles. As soon as the fighters arrived, one recalled, ‘ancient art and the works of Phidias were forgotten’.72 At the end of July, four of the leading fighters of the day – Jackson, Belcher, Gulley and Dutch Sam – were brought to Elgin’s for a ‘Pugilistick Exhibition’. Farington noted that the sculptor John Rossi particularly admired Dutch Sam’s figure ‘on account of the Symmetry & the parts being expressed’, and Sam is thought to be the model for Rossi’s 1828 sculpture, Athleta Britannicus (illus. 22).73 An attempt at pure classicism, we have no idea when looking at the sculpture that the model was a nineteenth-century Jew from the East End of London.74

|

21 Charles Turner after Benjamin Marshall, Mr John Jackson, 1810. |

The pugilist’s identity is also not apparent in Sir Thomas Lawrence’s portraits of his childhood friend, John Jackson. The first, exhibited at the Royal Academy exhibition of 1797, featured him, twice-lifesize, as Satan Summoning His Legions, to illustrate Milton’s line, ‘Awake, arise, or be forever fallen.’75 As Peter Radford notes, the painting makes an ‘obvious boxing pun about having been knocked down and having to get up’, but this was for private consumption. While the body was Jackson’s – Egan had described him as ‘one of the best made men in the kingdom’; others praised his ‘small’ joints, ‘knit in the manner which is copied so inimitably in many of the statues and paintings of Michelangelo’ – the face was that of the actor, John Kemble.76 The same combination featured in an 1800 painting of Rolla, from Sheridan’s Pizarro.77 Jackson’s muscular body was a useful starting point from which to paint grand subjects; his face, and profession, were not important.

| 22 Charles Rossi, Athleta Britannica, 1828. |  |

|

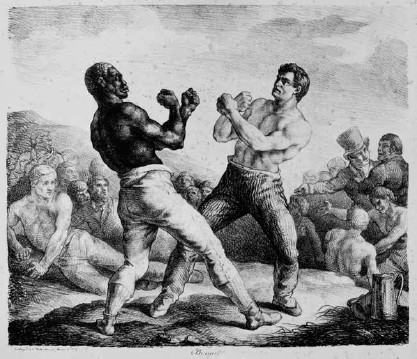

23 Théodore Géricault, Les Boxeurs, 1818, lithograph. |

Historical context returned, to be married with classical precedent, in the most widely known boxing image of the early nineteenth century, Théodore Géricault’s lithograph Les Boxeurs (illus. 23). On the one hand, it makes reference to contemporary events and setting. The boxers, dressed in modern clothes, are usually taken to be Cribb and Molineaux, and we can pick out a few men in suits and one in a prominent top hat in the crowd. Two beer tankards are prominently placed in the bottom right-hand corner. The anglophile Géricault had not attended either fight between the two men – he first visited England in 1820 – but he would have witnessed boxing matches in the Paris studio of painter Horace Vernet, a rendezvous for Restoration liberals, and perhaps, more importantly, he was familiar with English sporting engravings. His decision to depict the scene in a lithograph also signalled a commitment to the contemporary. Lithography was then a new technique and was associated mainly with political satire and other forms of ephemera.78

Géricault differs from Hogarth, however, in that he fuses references to the modern scene with allusions to classical and Renaissance art; he had recently returned to Paris after some years in Italy. Michelangelo’s influence, in particular, is apparent in the sharp contours, strained poses, bulging muscles and heroic stylization of the fighters.79 Several spectators are also portrayed naked to the waist. Most striking is one in the left foreground – perhaps having just been defeated himself? – who lies in a languid classical pose practically at the fighters’ feet. The mixture of realist and classical conventions is disconcerting, but allows Géricault to present the fight as both sharply contemporary and grandly mythical.

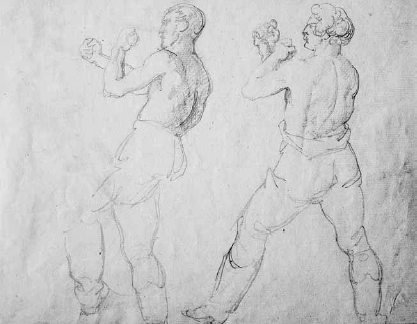

| 24 Théodore Géricault, Two Boxers Facing Left, 1818. |  |

Les Boxeurs positions its opponents very deliberately in the centre of the work, in identical monumental stances. They are static, unlike the fighters in Géricault’s more naturalistic pencil and pen studies of the same year (illus. 24). The black man wears white trousers; the white man’s trousers have black stripes. Géricault is obviously interested in tonal contrast, an interest that would be revived in George Bellows’s depictions of interracial boxing a hundred years later. But Géricault’s time, and his politics, were different from Bellows’s. Black men also feature in Géricault’s great paintings of 1819, The African Slave and The Raft of the Medusa, works that are often discussed in the context of liberal campaigns against France’s complicity in the slave trade, and Toussaint L’Ouverture’s heroic rebellion in Haiti.80 In most images of the contest between Cribb and Molineaux, the American appeared as little more than a caricature, often barefooted, ‘blackamoor’ (illus. 47). In Géricault’s lithograph, he is not only complementary but absolutely equal to his opponent; here, it seems possible that he might win.

‘THE ERA OF BOXIMANIA’

Works of the early twenties, such as Hazlitt’s ‘The Fight’ (1822), Egan’s Life in London (1821) and John Hamilton Reynolds’s The Fancy (1820) celebrated a cultural moment that was coming to an end. An elegiac air infects their exuberance. In 1818, Reynolds abandoned poetry (and boxing) to become a lawyer, and in 1820, about to marry, and with his good friend, Keats, very ill, he wrote The Fancy as a ‘final parting with his youth, his poetry, and the forbidden delights of youth’.81 But if Londoners were leaving the Fancy behind, out-of-towners were becoming increasingly interested. London’s sporting pubs were fast becoming tourist attractions, and places like the Castle Tavern in Holborn assumed legendary status.

In Howarth in Yorkshire, the Brontë children were keen readers of Blackwood’s Magazine, which was passed to them by a neighbour until 1831. One of their parodies, The Young Men’s Magazine, included an ‘Advertisement’ by Charlotte and Branwell, issuing a challenge to ‘a match at fisty-cuffs’.82 Their juvenilia is populated by young noblemen, always ‘masters of the art’, who set at each other ‘in slashing style’.83 Charlotte eventually lost interest, but Branwell continued to read Blackwood’s and Bell’s Life. Numerous references to, and sketches of, his pugilistic heroes can also be found in his letters.84

Brontë could not decide whether he wanted to be a painter or a poet. The poems he submitted to Blackwood’s were always rejected. In July 1835, he wrote a letter to the Royal Academy of Art asking for an interview. His biographers have debated whether he actually sent this letter, and whether, as a result, he visited London the following month. He claimed that he went. The uncertainty stems from the detailed account of London adventures he gave on his supposed return. Juliet Barker, who doubts the trip took place, maintains that Brontë’s impressions of the Castle Tavern, and his account of conversations with its landlord, Tom Spring, were lifted straight from the pages of Egan’s Boxiana and Book of Sports (1832), which gives a particularly lively and detailed description of the tavern and its patrons.85

A country boy who really did visit the pilgrimage sights of the Fancy was the poet John Clare. On his third visit to London in 1824, Clare was taken by the painter Oliver Rippingille to the Castle Tavern, and to Jack Randall’s Hole in the Wall in Chancery Lane – where Hazlitt’s ‘The Fight’ begins – and to see some sparring at the Fives Court. Clare later recalled:

I caught the mania so much from Rip for such things that I soon became far more eager for the fancy than himself and I watch’d the appearance of every new Hero on the stage with as eager curosity [sic] to see what sort of fellow he was as I had before done the Poets – and I left the place with one wish strongly in uppermost and that was that I was but a Lord to patronize Jones the Sailor Boy who took my fancy as being the finest fellow in the Ring.86

Iain McCalman and Maureen Perkins speculate that Clare may also have attended one of the numerous theatrical adaptations of Egan’s Life in London, and argue that ‘there can be little doubt that he modelled his own metropolitan tourist programmes on the “sprees and larks” of Egan’s fictional heroes’.87

In the Northampton asylum in which he spent the last years of his life, Clare adopted many pseudonyms and alter egos, including those of some of the prizefighters he had watched on that trip to London. Inventing new names was of course a speciality of prize-fighters, but Jonathan Bate speculates that ‘the persona of the pugilist became Clare’s stance of defiance’ in the violent atmosphere of the asylum.88 Clare was seen shadow-boxing in his cell, crying out ‘I’m Jones the Sailor Boy’, and ‘I’m Tom Spring’, or, as ‘Jack Randall Champion of the Prize Ring’, issuing a ‘Challenge to All the World’ for ‘A Fair Stand Up Fight’.89 On one occasion Clare (soon to write his own ‘Child Harold’ and ‘Don Juan a Poem’) even referred to himself as ‘Boxer Byron / made of Iron, alias / Box-iron / At Spring-field.’90 The personae of Box-iron and Boxer (Lord) Byron pull in different directions: Clare wanted to be both the self-made working-class prize-fighter and the kind of Lord who patronized such men. But his assumption of these roles brought no relief from his isolation and increasing alienation from both worlds. One letter (to an unidentified and possibly imaginary correspondent) laments that although ‘It is well known that I am a prize-fighter by profession and a man that has never feared any body in my life either in the ring or out of it . . . there is none to accept my challenges which I have from time to time given to the public.’91

Two months before he died, an ailing Branwell Brontë wrote to Joseph Leyland, signing off with the remark that he was ‘nearly worn out’. The letter was accompanied by a sketch of a man lying in bed and a skeleton standing over him. The skeleton is saying that ‘the half minute time’s up, so come to the scratch; won’t you?’ The prostrate man replies, ‘Blast your eyes, it’s no use, for I cannot come’, and above is written – ‘Jack Shaw, the Guardsman, and Jack Painter of Norfolk’. Painter had been defeated by Shaw in 1815 (just weeks before Shaw died heroically at Waterloo). The fight was largely memorable for Painter’s courageous resilience: he ‘received ten knock-down blows in succession; and, although requested to resign the battle, not the slightest chance appeared in his favour, he refused to quit the ring till nature was exhausted’.92

Branwell Brontë, a painter himself, died in 1848, and John Clare followed in 1864. Both men lasted longer than the Fives Court; built in 1802 at the start of pugilism’s vogue, it was pulled down in 1826 as part of the development of Trafalgar Square (illus. 49). The golden age of boxing was over.