CHAPTER SIX

Chinatown lies along the southern edge of downtown Boston. As Chinese immigrants arrived in Boston in the 1870s and 1880s, they set up shop along Harrison Avenue between Essex and Beach Streets and created a hub of restaurants and stores where they could socialize with their fellow countrymen. Women, on the other hand, were another story.

Boston’s Chinatown district started out as an ethnic enclave full of men. Many of these early immigrants had come to America to make money and left their wives behind to take care of their children, families, and in-laws in China. But aside from financial and cultural reasons, restrictive anti-Chinese immigration laws made it next to impossible for Chinese women to settle in the United States.

As a result, Chinatown started out as a big community of bachelors. In a neighborhood devoid of women and children, gambling and opium were welcome distractions. They were also the basis for a lucrative business that certain local factions wanted to control.

■ ■ ■

Shortly before 8:00 p.m. Friday, October 2, 1903, music filled the air on Harrison Avenue, the main thoroughfare of Chinatown. A street musician turned the crank of a hand organ while another played the piano. Suddenly the sharp cracking noise of gunfire punctuated the peaceful ambience. A bullet whizzed past one musician and struck the piano. Thirty-seven-year-old patrolman James W. Brooks had been working the Chinatown beat for nine years. He was standing on the corner of Beach Street and Harrison Avenue when he heard the gunshots. He ran down Harrison Avenue and saw a man holding a revolver in his right hand. Brooks reached and tried to grab the gun away, but the man pulled his hand back. The gunman stooped over, and Brooks pushed him up against the side of a building. The tussle continued until Patrolman James Hanlon arrived on the scene and helped Brooks wrestle the weapon away. Brooks then noticed the man take something out of his left-hand pocket and throw it into the doorway at 38½ Harrison Avenue and then say something in Chinese to another man standing nearby. That man, later identified as Charley Chin, picked up the item from the doorway and ran off. As Brooks chased Chin, he saw him toss the object into an alley on Oxford Place. Brooks finally caught up with Chin, grabbed him, and walked him back to the spot where he’d thrown the item away. Brooks asked a fellow officer to pick up whatever it was. The patrolman leaned over, picked it up, and then turned to show Brooks what it was—a hatchet.

The shooting victim, Wong Yak Chong, was found lying on his back in the doorway of 48 Beach Street, which was the headquarters of the Hip Sing tong. He was unconscious and bleeding, and would not survive the night.

Chong’s murder made headlines in Boston. “Highbinder War Coming,” declared a headline in the Globe the next day. “Chinese Gamblers Bring Hatchet Men, Employ Them To Kill Their Rivals.”

Police determined that Chong belonged to the Hip Sing, and he’d been murdered by a member of a competing organization known as the On Leong tong.

At that time, these two rival Chinese organizations (known as tongs) operated as merchant associations, and were in many ways similar to other fraternal organizations. But they also reportedly had their hands in illicit activities as well. One unnamed police official spoke to a Globe reporter and hinted that the department was preparing for reprisals. What he said also revealed the flagrant racism that existed at the time.

“These Chinamen are such liars that we couldn’t believe half they told us,” he said, “but lately we have heard so much about coming trouble that we have been unusually alert.”

Police decided to be proactive about the situation. Boston police captain Lawrence Cain said it was the first time that a “bloody feud” had broken out among the Chinese in Boston, and the police were ready to “take every precaution, even if innocent men are brought to the station.”

■ ■ ■

A funeral for Wong Yak Chong was held on Sunday, October 11, and thousands of people watched the procession through Chinatown to Mount Hope Cemetery. Later on that evening, as residents of Chinatown were winding down from the eventful day, policemen and immigration officials descended upon the neighborhood and began rounding up Chinese residents. Anyone who couldn’t produce their papers immediately was taken into custody. One Chinatown resident was stopped as he was going into his house on Oxford Street.

“Got your papers?” asked an officer.

“No. But I was born in New York,” the man replied.

“Can’t help it,” snapped the officer. “Guess you’ll have to go with the bunch.” The officer grabbed the man, walked him over to Harrison Avenue, and then forced him into the back of a horse-drawn wagon filled with dozens of other Chinese men.

This was repeated over and over again. It didn’t matter if people had left their papers at home, or claimed they were born in the United States—if they didn’t have their papers, they were shoved into one of the police wagons and taken to the federal courthouse. All told, more than 200 Chinese men were rounded up in the dragnet, and approximately fifty were eventually deported to China. George Billings, the immigration officer for Boston, was pleased with the results. “We have had it in mind for a long time to do something of this sort,” Billings told a Globe reporter. “It required something like the murder of Chong, however, to give us the proper excuse for taking action.”

The racial motives behind the massive sweep were clear. The two suspects charged in the killing of Wong Yak Chong—Charlie Chin and Wong Chung— were already in custody at the time of the raid. They were indicted on charges of second-degree murder and were arraigned on November 11, 1903.

Chung belonged to the On Leong tong. He later testified that he used his revolver in self-defense because people, presumably members of the rival Hip Sing tong, were shooting at him. Chung said he’d received death threats from the Hip Sing before.

Chin testified that he was finishing dinner in a restaurant on Harrison Avenue when the shooting began. When he went outside to look, someone told him to pick up the hatchet on the sidewalk, and he did as he was told. He then headed toward Oxford Place, where he was arrested by Patrolman Brooks.

Chin’s lawyer, Charles W. Bartlett, accused the police of using unnecessary force and claimed police threw water on Chin while he was locked up in his cell and that a police inspector broke Chin’s nose.

It was to no avail, however. The two men were convicted of second degree murder and sentenced to life in prison. Nearly a decade later, the governor issued them both pardons, under one condition: They had to go back to China and never return to the United States.

■ ■ ■

On Friday, August 2, 1907, the mercury had reached 80°F in Boston. The sidewalks felt warmer and more crowded than usual as visitors from all over ventured into the city to celebrate the final days of Old Home Week, a weeklong celebration that had kicked off the previous Sunday. In Chinatown that evening, tourists leisurely strolled around, taking in the sights and sounds of the neighborhood. Chinese men sat in chairs outside, seeking relief from the sweltering heat of their apartments. They smoked pipes and chatted, relaxing after a long day of work.

On patrol that night was Officer Brooks. He was still assigned to Division 4, and worked out of the police station nearby at 56 Lagrange Street. Just before 8:00 p.m., he was walking along Harrison Avenue. When he reached the Essex Street post office, he heard a loud BANG. At first, he didn’t think much of it. Residents of the neighborhood had a permit to light fireworks that evening, and he assumed the noise was a firecracker. But when more loud bangs followed, Brooks began running toward the source of the noise. As he ran he tripped and fell onto the sidewalk. He looked back, wondering if someone tripped him, then got back up and continued running toward the sounds of gunfire.

Little did he know, ten members of the Hip Sing tong had showed up at Oxford Place, one of the busiest areas of the neighborhood. They had pulled out long-range revolvers and started shooting as they made their way through Oxford Street. Bullets smashed through an apartment window at 3 Oxford Place, and the two residents inside dove onto a bed. Outside, residents ducked their heads, scurried into alleyways, and crawled on the ground, desperately trying to avoid being hit.

When all was said and done, the mass shooting left four people dead and seven others wounded. It would go down in history as one of the bloodiest incidents in Boston’s “Tong Wars.”

In the aftermath, tips poured into the Boston police, but officers were wary of how many On Leong tong members were enthusiastically pointing fingers at their rivals. It was difficult to ascertain who was telling the truth, and who was trying to settle old scores.

Eventually, ten men were arrested in connection with the massacre. Nine of them were charged with murder, and one, Warry S. Charles, was charged with being an accessory before the fact.

Charles was well-known and well connected. The New York Times boasted that he was “the most prominent Chinaman in Boston.” Other newspapers at the time noted how Charles wrote and spoke English fluently, dressed in suits, and ran a successful business. One of his sons was a policeman in New York City.

Born in China in 1857, Charles immigrated to the United States as a young boy and went on to work in several cities, including San Francisco, New Orleans, and Omaha, where he met his future wife, Mary Whiting, the daughter of a prominent businessman.

While in New York, Charles worked as an interpreter and inspector for the government. Charles said he refused to take bribes, and quickly became a target of the On Leong tong.

Charles reached out to New York Police Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt and told him that policemen were allowing gamblers to operate in Chinatown because they were getting paid off by the On Leong tong. Charles told Roosevelt that if he assigned two detectives to work with him, he could help the police break up the gambling rings. Alas, nothing ever came of his request.

But Charles soon gained a reputation on the streets. Many criminals didn’t like what he was doing. One time, Charles was beaten up by a member of the On Leong tong. Another time, an opium dealer aimed a slingshot at him, striking him in the head with projectiles and leaving him with gaping wounds on his face and scalp. After surviving those assaults, Charles left New York and went to work as a translator and interpreter for the courts in Boston. He also started a laundry business. In 1903 Charles helped establish a branch of the Hip Sing tong in Boston and put $400 toward establishing its headquarters at 48 Beach Street in Chinatown.

A few days after the August 1907 shootout, Charles was arrested at his office at 17 Myrtle Street, accused of masterminding the attack. His friends claimed he was being set up by enemies, but he and the other nine defendants went to trial in February 1908. A month later, on March 7, 1908, the jury returned the verdict. Eight of the defendants were found guilty of murder in the first degree (one of the defendants, Yee Wat, died in prison while the trial was under way), and Charles was found guilty of being an accessory. All nine would face the death penalty.

Charles’s wife spoke out in defense of her husband. She said Charles had served the government faithfully for many years, and his only fault was that he was honest. She was convinced that his enemies had paid off witnesses to lie in court.

“They have been after Charles for the last twenty years, and now they seem to have got him where they want him,” she said. “But the fight is not over yet.”

In August 1908, the charge against Yee Jung was dismissed and he was released. Wong Duck, Wong How, and Dong Bok Ling were also eventually released due to lack of evidence.

On October 12, 1909, three of the defendants—Hom Woon, Min Sing, and Leong Gong—were killed in the electric chair, one after another, at the state prison in Charlestown.

Joey Guey and Warry Charles ultimately escaped being electrocuted. Their death sentences were commuted, but they still had to remain behind bars for the rest of their lives. Charles died in the prison hospital in 1915.

■ ■ ■

On June 5, 1930, at 2:45 a.m., a man armed with a revolver opened fire at Hip Sing headquarters, which was then located at 49 Hudson Street. More than two dozen Hip Sing members dove to the floor and tried to take cover. Two men fell down some cement steps as they scrambled to get out of the way. Miraculously, no one was hit. The lone gunman, believed to be a member of the On Leong, escaped.

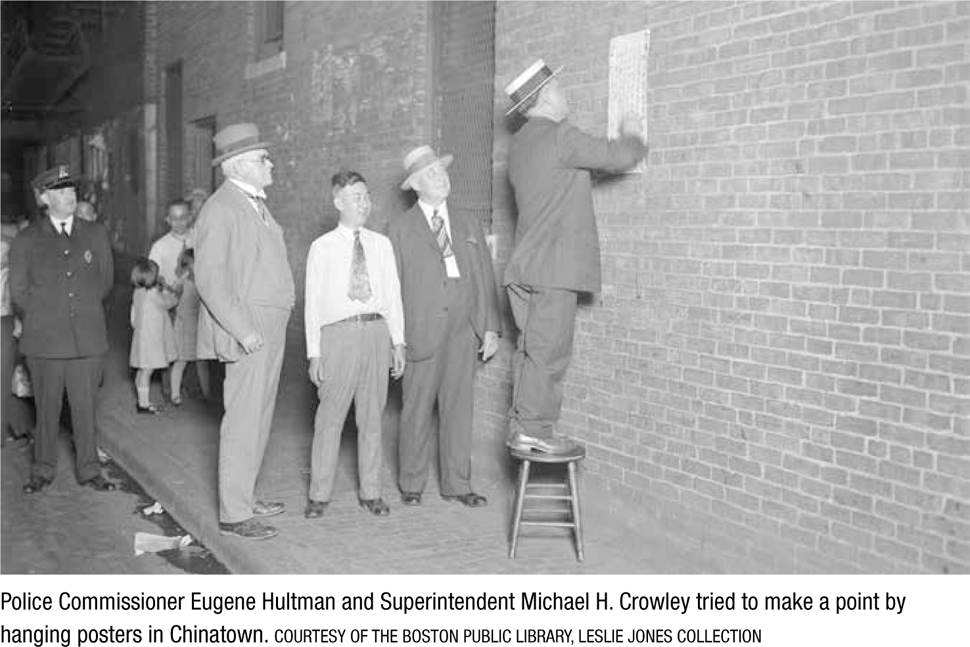

Later that evening, Police Commissioner Eugene C. Hultman and Superintendent Michael H. Crowley paid a visit to Chinatown. They brought signs with them with the following message written in Chinese:

The police commissioner of Boston says he wishes to protect the Chinese residents of Boston and that the tong wars must stop.

The commissioner says to the Chinese people that he is their friend and will continue to be. But shooting and other fighting must stop or he will stop it by force.

The police are your friends. They will protect you but all Chinese must do their part to keep the peace. All tong wars must stop.