CHAPTER ELEVEN

January 1930 marked the start of a new decade, and Bostonians bid good-bye to the Roaring Twenties and embraced what they hoped would be a positive future. For Patrolman Daniel J. McDonald, the new year brought with it a new work assignment. On January 9, McDonald was transferred from his post in South Boston to the Boston Police Department’s automobile patrol squad, affectionately known as the “Flying Squadron.” The unit was responsible for patrolling streets all over the city, especially high-crime areas, from 5:45 p.m. to 7:45 a.m.

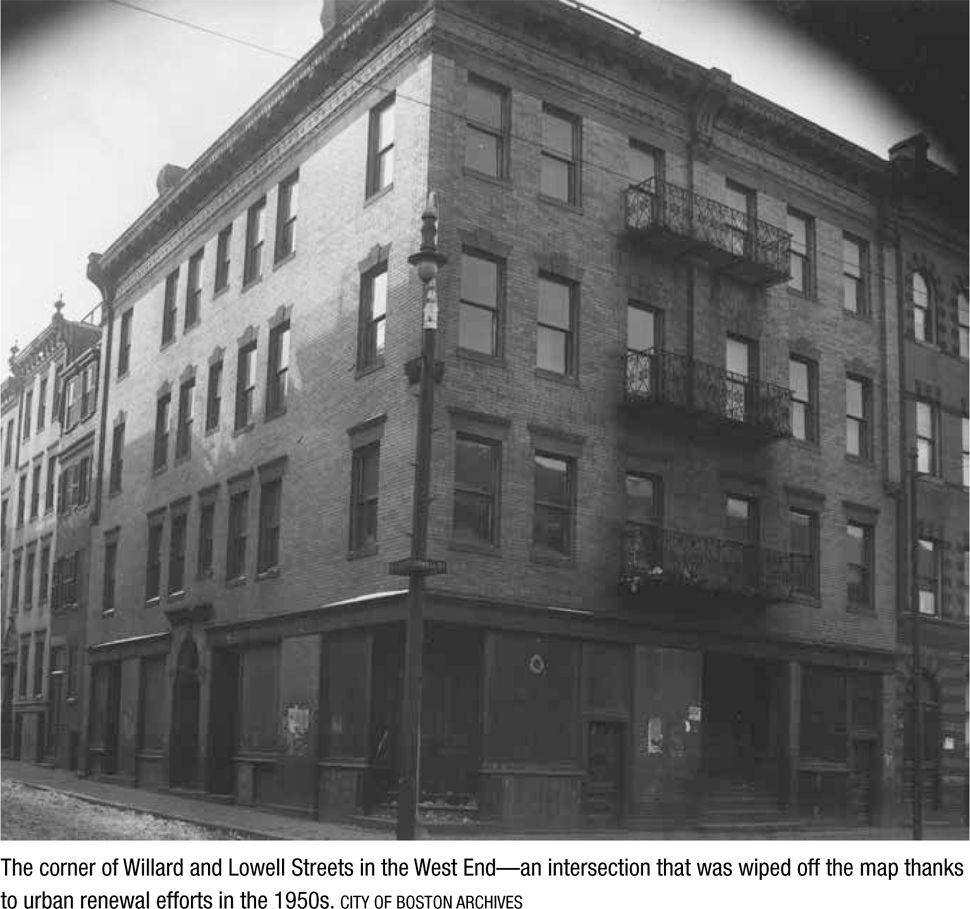

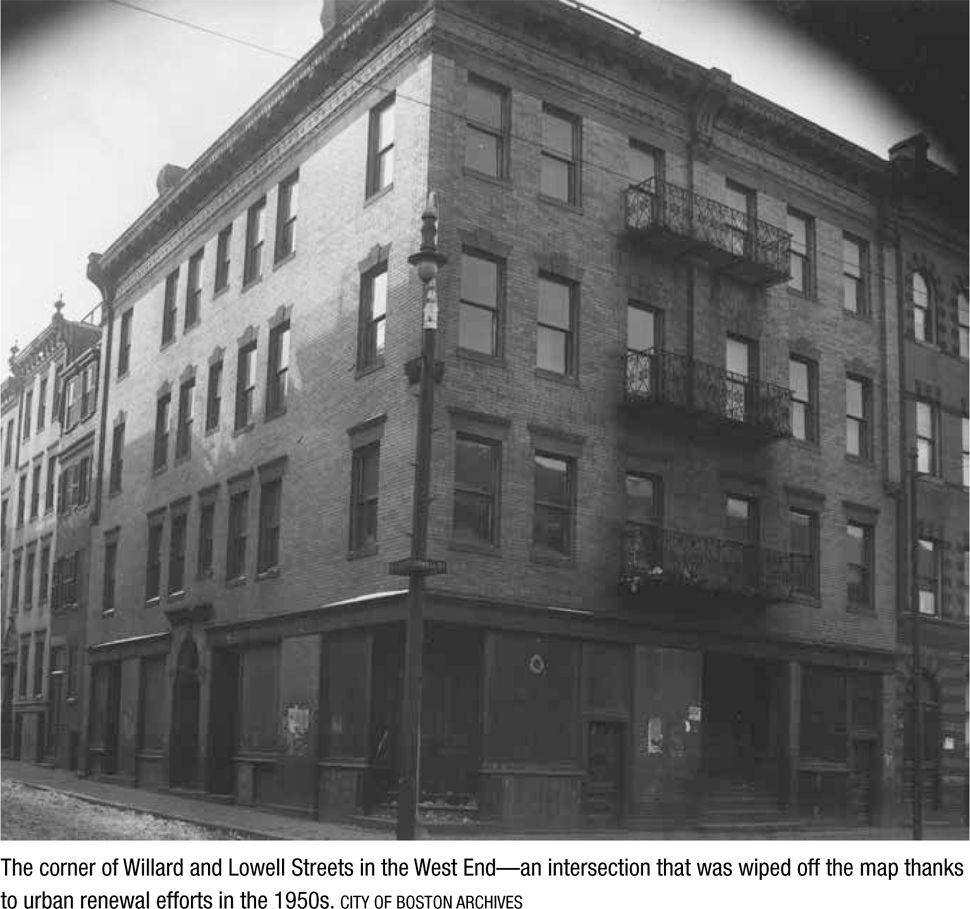

On the evening of November 11, 1930, McDonald was on duty with the Flying Squadron. While McDonald was riding around the downtown city streets, thirteen-year-old Stanley Skeiber was hanging out with other kids on Willard Street in the West End. Skeiber was the son of Polish immigrants and lived on Allen Street in the West End (a few doors down from “Mickey the Wiseguy”) in a diverse neighborhood full of immigrant families. Skeiber and his friends noticed a well-dressed man strolling through a vacant lot, but they didn’t pay much attention, as many used that well-worn path as a shortcut between Barton and Willard Streets. As the man strolled under the elevated railway and approached Willard Street, his hands firmly tucked into his coat pockets, a sedan on Lowell Street suddenly turned the corner onto Willard. A loud blast caught the boys’ attention, and a burst of orange flame appeared from the passenger side window. The man crumpled to the ground. The sedan sped down Willard Street, turned the corner onto Leverett, and was gone. Skeiber and the other boys started running down the street in the direction the car had fled. They ran until they met up with Patrolman Walter J. Kenney, whom they told about the drive-by shooting. Kenney raced over to the shooting victim, who was lying on the ground and bleeding from several gunshot wounds to the head. His name was Samuel Guida, and he was thirty-five years old. He had been killed instantly. He never saw it coming—his hands were still tucked into his pockets.

The kids had been quick enough to read the license plate number off the car, and relayed that to police, who then sent it out over teletype from police headquarters. Patrolman Daniel McDonald of the Flying Squadron gave the plate number to Traffic Officer Cecil V. Craig and Patrolman Sylvester W. Murphy, who were stationed at the intersection of Tremont Street and Stuart Street. Right after getting the number from McDonald, they saw the sedan go by them on Tremont Street. Both officers started running after the vehicle, which was moving slowly through traffic. Craig ran in front of the vehicle, Murphy jumped on the running board, and they forced the driver to stop on Hollis Street. The three people in the car, two men and a woman, were then taken in for questioning. The officers were commended by Police Commissioner Eugene Hultman for their actions in the wake of the shooting.

Stanley Skeiber testified in court, and had to prove his memory was reliable. The boy was asked to look at a series of numbers on a piece of paper, then it was taken away and he was asked to recite the numbers. Each time he remembered them correctly.

Justice was not to be had for Guida, though. Two suspects were originally charged with the murder and held at Charles Street Jail. A judge later found no probable cause for one, and he was released. The other was held for the grand jury, but ultimately was let go. Guida’s murder was never solved.