CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

David J. “Beano” Breen grew up in Boston’s Kerry Village, a tiny, predominantly Irish enclave nestled between the theater district and Back Bay. The narrow cobblestone streets were lined with redbrick row houses with granite foundations. The neighborhood looked much like it did in 1825, when the streets were first laid out and the first homes were built. Today, it’s known as Bay Village, and it’s the smallest neighborhood in the city of Boston.

Breen was born in 1892. He was an only child, and his father died when he was a baby. His mother ran what was known as a “blind pig,” a kitchen barroom where she poured shots of whiskey for whomever was willing to pay the going price. Authorities tried to crack down on her unlicensed bar operation, and police raided the Breen household often. As a young boy, Breen had seen the cops crash through his mother’s kitchen too many times, and had been knocked around by these big men wearing the high-necked frock coats with winged collars and bobby helmets. He couldn’t stand the sight of their nickel-plated badges, or their belt buckles bearing the city seal. He despised them all.

Breen spent much of his childhood on the streets, and got in trouble with the law at an early age. He was known as a bully, and had to go to juvenile court to answer to charges of assault and petty larceny. He dropped out of school when he was fourteen, and he devoted his free time to boxing and working out at the gym. He stood 5 feet, 9 inches tall, and weighed 130 pounds—and he was still growing. He quickly developed a muscular build.

One summer day in 1910, eighteen-year-old Breen was standing on a street corner in his neighborhood when a cop told him to move along. Breen refused, and pummeled the officer along with another patrolman who came to help. Breen was charged with two counts of assault and battery and fined $40.

The following summer, he assaulted another police officer, was arrested, and fined $20.

Police Superintendent Michael H. Crowley was concerned about Breen, and decided to meet with him. It wasn’t a mutually agreeable appointment, however. Crowley had two of his men pick up Breen and bring him to his office for questioning. When they brought Breen in, Crowley tried to be nice. But Breen wasn’t going for it. As Crowley started to speak, Breen cut him off.

“Shut up,” Breen said. “I hate cops.”

“Don’t be a sucker,” Crowley said. “You’d like to make good as a fighter, wouldn’t you?”

“What’s it to you?” Breen said.

“Cops can help fighters a lot on the way up,” Crowley said.

But Breen wouldn’t have it. He told Crowley he’d never take anything from a cop. Crowley told his detectives to turn him loose.

At the age of twenty-two, Breen lived with his mother at 8 Melrose Street, in a three-story brick Greek Revival row house that was built in the second quarter of the nineteenth century. He had given up on his boxing career and focused his attention on gambling and causing trouble.

At 2:35 a.m. on May 30, 1914, a patrolman from the East Dedham Street station noticed Breen with a group of young men tossing bottles into the street at the intersection of Columbus Avenue and Warren Avenue where “dope fiends” were known to congregate (thus begat its nickname, “heroin square”). When the patrolman tried to disperse the group and told them to go home, Breen responded by punching him in the face. The patrolman swung his nightstick repeatedly, hitting Breen in the head. With each swift crack of the baton, Breen’s scalp split apart, and began to spew blood. His head was cut open in four places when he was finally taken into custody. It was just another night on the town for Breen, and one of many run-ins with the cops.

Breen ran craps and poker games out of a place on Harrison Avenue. One of his regular clients was Charles “King” Solomon, a young entrepreneur who was making lots of money from distributing morphine, opium, and heroin.

At the age of twenty-eight, Breen was still living with his mother and listed his occupation as an accountant working the film industry—a claim that was not as far-fetched as it might sound. It was 1920, and his neighborhood was becoming known as Boston’s “motion picture district” and was a hub for film distribution companies. By 1927, Paramount News operated out of a building at 36-38 Mel-rose Street, just a few hundred feet down the block from Breen’s home. (There’s a plaque on the building today.)

Just after 2:00 a.m. on February 24, 1920, a rookie policeman from Station 5 named Henry C. Elliott noticed Breen and his cohorts starting a fight with a group of African Americans who had just left a nearby dance hall. (Elliott had joined the force in October 1919.) Elliott stepped in to quell the disagreement, and Breen allegedly attacked him. The young officer drew his revolver and pulled the trigger. Then he fired again. The two bullets shattered Breen’s left ankle. Breen’s buddies tried to carry him away from Arlington Square, but he collapsed to the ground. He was brought to the hospital and, once again, charged with assaulting an officer.

On the morning of May 11, 1920, Breen hobbled into Municipal Court on crutches. He was accompanied by his mother, and a large crowd was waiting for him in the corridor. The spectators appeared to be disappointed when Breen’s lawyer announced that he would plead guilty to assaulting Elliott and using profanity.

After the shooting, Breen went to Canada for a while. He moved to Montreal, got a place on Saint Catherine Street, and began working in the liquor trade on the other side of the border. Prohibition was now in effect, and he and Solomon kept their illicit business interests flowing by smuggling liquor and drugs across the Canadian border.

Liquor and drugs from Canada were hidden in bales of hay and taken across the border to a summer camp just outside Malone, New York, and the contraband eventually made its way to Boston. While Breen worked in Canada, Solomon paid protection to law enforcement officials to ensure their goods moved along from Montreal to Boston without any problems.

When Breen returned to Boston, he operated the Neptune Athletic Association, which was a speakeasy located on the second floor of 358A Tremont Street in the South End. The club was constantly raided by police. Captain Jeremiah Gallivan once said his men raided the place more than seventy-five times and not once did an officer ever find liquor.

The police would come and remove the heavy steel doors Breen installed. This happened over and over again. Finally, Breen had enough. According to local lore, he commissioned some students from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to design the strongest door possible. He installed the custom-built door made of steel and concrete and waited for the next police raid. Sure enough, the cops showed up, and it took them hours to get through the door. It was the forty-third door of Breen’s to be removed. So Breen took the police department to court. It was a lengthy legal battle. Breen had his lawyer file a lawsuit against the police to stop them from raiding his private club and stealing his doors. He was able to get an injunction in court (which the police promptly appealed).

After Prohibition ended, Breen branched out into other business ventures. In 1935 Breen operated the Cosmos Club, which was located on the second floor of 92 Broadway. But he would only have a couple of years to enjoy that venture. Like his old friend Charles “King” Solomon, Breen met an untimely death.

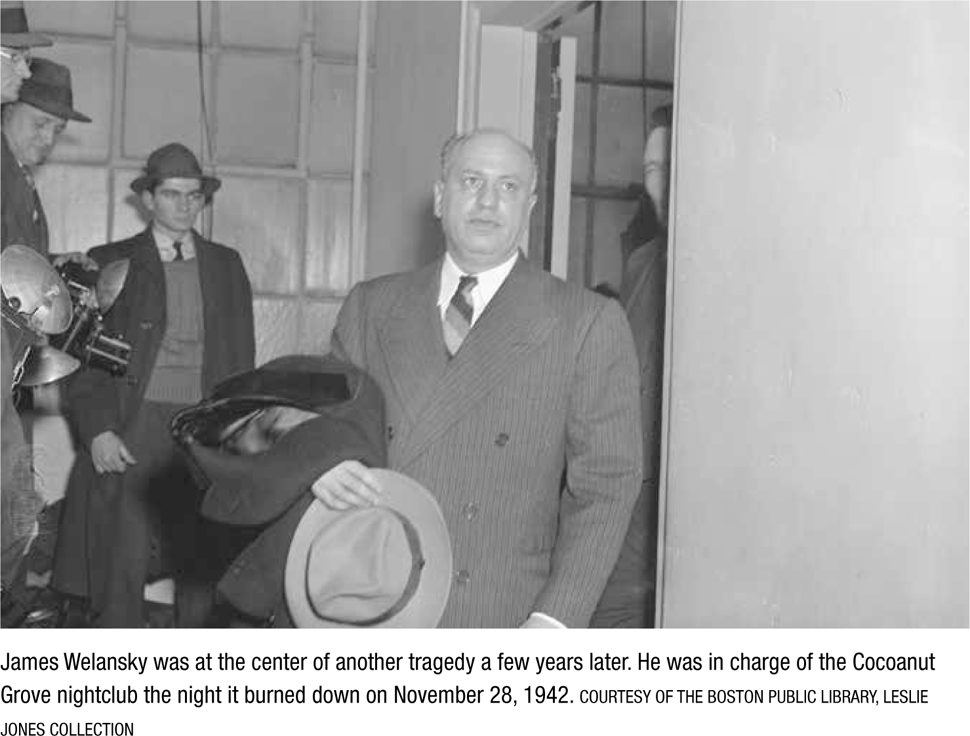

Breen was last seen alive in the lobby of the Metropolitan Hotel at 315 Tremont Street on December 17, 1937, which was managed by James Welansky. At about half past midnight Breen was chatting with the hotel manager, James Welansky, by a table across from the telephone booths. Welansky was also the founder of the Theatrical Club, an after-hours club and jazz joint on the corner of Warrenton and Tremont Streets. When he and Elias “Al” Taxier first opened the Theatrical Club, they booked a jazz band to play to a completely empty room. When people passed by on the street, they could hear the music and naturally inquired about the new establishment. Taxier turned every one of them away, and said the place was booked. Word quickly spread around the city about the new, hot club that opened. It was a genius way of marketing the club. Tommy Dorsey, Benny Goodman, Fats Waller, and other notable musicians were known to stop by there.

That night, Breen had just come from a party at the Kenmore Hotel (reportedly it was a stag party for a West End politician, and many big-name guests were there). Suddenly the sounds of gunshots echoed across the lobby. One piercing blast, followed by another, and another, and another, and another. Breen tried to get away from the line of fire, but one of the bullets struck him in the neck. He managed to get outside and hail a taxicab to take him to the hospital, where he eventually succumbed to his wounds.

Meanwhile, Welansky turned to the desk clerk and told him to call the police. Then Welansky walked into his office and proceeded downstairs to the Theatrical Club, which was on the lower level of the hotel. He then exited through the club’s Warrenton Street entrance. First he walked to Park Square, by the Public Gardens, and then he went back to the hotel and got into his car, which was parked at the Broadway entrance to the hotel. He then drove to a friend’s house and spent the night there. The next day he took a train to New York. From there he called his wife, and the next day boarded a plane to Miami. He spent the next ten weeks in Florida.

“I could not sleep,” Welansky later recalled. “I saw that Breen was murdered in the papers the next morning. I don’t know why I didn’t report to the police. I was frightened and confused. I suppose it puts me in a bad light.”

Police recovered four bullets from the hotel lobby. The fifth bullet—the one that killed Breen—entered through his left earlobe and went upward through his neck. The Boston Police Department’s ballistics expert concluded that Breen had been shot at close range, and that the gun had been as close as 4 inches away from him when he was struck. This made Welansky a prime suspect.

In March 1938, Welansky showed up at Station 4 to talk to the police. He was accompanied by his brother, Barnett Welansky, who was a lawyer, and Barnett’s law partner, Herbert Callahan.

“Is Captain Connolly in?” asked Welansky.

“No, he’s home eating,” said Bailey.

“I’m James Welansky. I want to talk to the captain.”

Welansky told police that he had known Breen for years, and they had practically grown up together in the South End. Welansky said he heard shots, and saw Breen crouch down behind the table, then he ran to the right of the table, toward the Tremont Street entrance of the hotel. Several witnesses—including the desk clerk and bellhop—testified that they saw a tall, thin man with dark glasses enter the lobby, fire a pistol, and then run out the door.

Two months later, in May 1938, Judge Charles S. Carr said, “At the inquest, over a score of witnesses were heard by me. Except for the witnesses connected with the Police Department and the doctors, and possibly two others, I am satisfied that every other witness lied to me. Some were afraid to tell what they knew; others withheld facts because they did not want the truth to be known. But out of the police evidence and out of the grains of truth let fall by others, I think a conclusion can be reached.”

Welansky was held without bail in the Charles Street Jail. But the evidence wasn’t enough to convince a grand jury to indict him. On July 1, 1938, Welansky appeared in Suffolk Superior Court. After the grand jury refused to return an indictment, Welansky was arraigned as a material witness in the case and the judge set his bail at $5,000. Welansky paid the bail and walked out of the courthouse, under a cloudy sky, a free man.