CHAPTER THIRTY

Berkshire Downs was a racetrack in western Massachusetts that the FBI once described as “one of the most ambitious projects attempted by organized crime in New England.” Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin were reported to be among the early investors. Raymond L. S. Patriarca and Tommy Lucchese were linked to the track as well.

The track was located on Route 20 in Hancock, a tiny rural town at the west-ernmost edge of Massachusetts, bordering New York. It was a short drive from Pittsfield and about a half hour from Albany.

Dr. Charles Furcolo, a surgeon whose son was the governor of Massachusetts at the time, was instrumental in launching the new racetrack, but he didn’t want the public to know he was an investor, so he got a front man, Charles Carson, to act on his behalf.

In late August 1960, just before the track was going to open, Berkshire Downs was in dire need of money. “We were down to our last dime,” recalled Carson.

Carson and Dr. Furcolo went to Providence and met with B. A. Dario, the owner of Lincoln Downs, a successful racetrack in Rhode Island.

They negotiated a deal with Dario. He’d get 30 percent of the voting stock, serve as general manager, receive $25,000 a year for ten years, and have full voting rights for ten years. In return, he invested $50,000 and guaranteed a $300,000 loan from Sportservice, a subsidiary of Emprise.

After that, though, Carson noticed a new face showing up to Berkshire Downs board meetings. Dario introduced him to Carson as “Ray.” Carson asked Dario who Ray was, exactly.

Carson recalled Dario’s reply: “Oh, Charlie, he has got unlimited wealth. Any time we need a hundred grand, I will get it just like that.”

When the Berkshire Downs opened in September 1960, there were close to seven hundred horses stabled at the track—which meant thoroughbreds outnumbered residents in the town of Hancock, which was home to fewer than five hundred people. Construction crews had worked up until the last minute to get ready. The oval-shaped, 0.5-mile track was made of sand and loam.Opening day was gray, damp, and chilly, but thousands of people showed up. Traffic backed up onto Route 20 before the first race. Cars with license plates from Connecticut, New York, and Massachusetts could be seen in the parking areas, but the lots were far from being full.

The first race of the afternoon began unceremoniously, with the announcer barking, “They’re off!” Spectators joked among themselves that the winner of that race—a horse named Pay Mike—had set a track record. It rained through the first three races.The track had gotten off to a bad start.

The owners tallied a final headcount of about 6,000 on opening day, while the local papers reported a handle of $168,085. But there was a problem, and it was a big one. The owners needed at least a $200,000 daily handle to break even.

In an effort to make more money, the following year Berkshire Downs unveiled a new grandstand that could accommodate up to 3,500 people, boosting the track’s overall capacity to 10,000. There was a cocktail lounge, and more selling windows where bettors could place wagers. The president optimistically predicted that the track would average between $350,000 and $400,000 in bets a day.

In September 1962, Berkshire Downs made headlines when a United Press International story reported that Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin had been elected to the track’s board of directors. A decade later, Sinatra would be called to testify in front of Congress and explain his involvement with the track. He appeared before the US House of Representatives Select Committee on Crime on July 18, 1972.

Sinatra walked into the Cannon House Office Building, a grand building on Independence Avenue in Washington, DC, with a limestone and marble facade and Doric columns, and made his way to Room 345. The cavernous hearing room was impressive, with a soaring ceiling and Corinthian pilasters on the walls. It was lit by six windows and four three-tiered crystal chandeliers. Sinatra, however, was none too pleased.

Joseph “The Animal” Barboza had previously been called to testify before the committee, and what he said shocked them, and apparently surprised Sinatra, too. Barboza had claimed that Sinatra “fronts points” for Raymond L. S. Patriarca and Jerry Angiulo in the Fontainebleau Hotel in Florida and the Sands in Las Vegas.

Representative Claude Pepper, a seventy-one-year-old Democrat from Florida, was the chairman of the committee. He asked Sinatra if he wanted to say anything before the interrogation began. The conversation then proceeded as follows:

Sinatra: I do, Mr. Chairman. I would like to clarify the situation that arose here when I was away regarding a felon who was a witness in this room, who irresponsibly made a statement . . .

Pepper: I would be glad to have you make any statement you would like to make.

Sinatra: I am doing it right now.

Pepper: Very good.

Sinatra: I think it was indecent and irresponsible for a man to be allowed to come in and bandy my good name about without any foundation whatsoever, in order to better his position. Why? I don’t know. And I would like to do something about that now. I ask the committee to help me do something about that.

Phillips: The committee was prepared, Mr. Sinatra, to do something about that. The affidavit . . .

Sinatra: What I am really trying to say is, why didn’t the committee refute it when he said it? . . . This bum went running off at the mouth. I resent it. I won’t have it. I’m not a second-class citizen. Let’s get that straightened out.

Sinatra held up a newspaper article and read the headline: How do you repair the damage that was printed in the newspapers? Witness links Sinatra with reputed Mafia figure. That’s charming, isn’t it? That’s charming. And it is all hearsay testimony to begin with, is that not true?

Sinatra then explained to the committee how he got involved with Berkshire Downs. Sinatra said Salvatore Rizzo, the president of Berkshire Downs, approached him in Atlantic City in 1962 and asked him if he wanted to invest in the track. Sinatra said he ran the idea by his longtime lawyer, Milton Rudin, and ultimately invested $55,000 in late August 1962 for a 5 percent interest in the track.

Sinatra’s lawyer, Milton Rudin, testified that they thought it was a smart investment, and that he checked to make sure Rizzo was legit.

Rudin said that it was a relatively tiny investment, given the size of Sinatra’s income, and only represented one small sliver of Sinatra’s business interests, of which there were many—and even more possibilities.

“Any time Mr. Sinatra appears anywhere,” Rudin told the committee, “there are at least ten propositions thrown at him.”

The committee then asked how Dean Martin got involved with the venture:

Sinatra: I guess you ought to ask Mr. Martin?

Phillips: We did and he said you involved him.

Sinatra: Why isn’t he here?

Phillips: We asked him and he gave us full cooperation.

Sinatra: Why didn’t you ask me the same way you asked him?

Phillips: We couldn’t find you, Mr. Sinatra.

Sinatra: That is a lie—you couldn’t find me.

Phillips: It was very difficult, believe me.

Phillips: But you say you don’t know how Mr. Martin got engaged in this transaction?

Sinatra: He was probably drunk and got mixed up in it.

Later in the hearing, Sinatra acknowledged that he may have asked Martin to join him in his racetrack investment. Rudin went on to explain to the committee that Dean Martin never actually put any money into the track. Rudin said the FBI did call and ask to interview Martin in 1963, and he was cooperative. Rudin said he sat in on that meeting, and the FBI agents brought up Berkshire Downs, and the fact that Martin had been named as an officer or director of the Hancock Raceway Association.That’s when Rudin and Martin informed them that he had not invested in the track, nor had he given any consent for his name to be used in association with the track. Rudin said he told the FBI that Sinatra had made an investment in the track.

“A phone tap by the Justice Department of Patriarca’s office on August 24, 1962, revealed that Mr. Patriarca was informed that the track was going to put you on the board of directors ‘to add a little class to the track,’” said Representative Sam Steiger, a Republican from Arizona. “And I will tell you, Mr. Sinatra, in my opinion, it was desperately in need of a little class at that point.”

Sinatra said he didn’t know he’d been named an officer of the track until he read about it in the papers. When he found out, he wanted out. Rudin said he requested Sinatra’s money back in March 1963, and they received the $55,000 back in July.

Sinatra said he never met Patriarca in his life. Sinatra also said he never went to Berkshire Downs, not even once, and he didn’t know anyone else involved with the venture, besides Rizzo.

“You testified that you never met Raymond Patriarca,” said Sandman. “You wouldn’t know him if you saw him?”

“Not if I fell over him,” said Sinatra.

The following day, on July 19, 1972, Raymond L. S. Patriarca was called to appear before the US House of Representatives Select Committee on Crime. Patriarca was an inmate in the federal penitentiary in Atlanta, Georgia, and he was accompanied by his lawyers, Harvey Brower and Robert Napolitano.

Pepper took the lead in questioning:

Chairman Pepper: Mr. Patriarca, were you a stockholder in the Berkshire Downs Racetrack in Massachusetts at any time during 1961 or 1962?

Patriarca conferred with his lawyers.

Patriarca: I decline to answer on the ground of the fifth amendment.

Pepper: Were you in a room at the time that a board meeting occurred of the directors of the Berkshire Downs Racetrack in Massachusetts? In 1961, when another party was touched on the shoulder and later slapped by you, not in the face, but on the body, and told to sit down in the presence of the board of directors of the Berkshire Downs Racetrack?

Patriarca conferred with his lawyers.

Patriarca: I decline to answer on the fifth and sixth amendment.

Pepper: Do you know Mr. Frank Sinatra?

Patriarca: I never met the gentleman in my life. The only time I have seen him was on the television.

Pepper: Did you know that Mr. Sinatra was an officer and member of the board of directors of, and a stockholder of, the Berkshire Downs Racetrack in Massachusetts from August 1961 to March 1962?

Once again Patriarca conferred with his lawyers.

Patriarca: Just what I read in the papers. I don’t know the dates, but it was in the papers. In fact, I read it in the paper down here yesterday morning.

Pepper: Do you know, or have you read in the paper, about anybody else having been a stockholder of, or an officer or director of, that track in 1961 or 1962?

Patriarca conferred with his lawyers.

Patriarca: Yes, I read.

Pepper: You have read in the paper about others?

Patriarca: Yes; one other.

Pepper: Who was that?

Patriarca: Me, sir.

Pepper: Who?

Patriarca: Myself. It said I had $215,000 invested in it. I wish I did. I never had $215,000 in my life, let alone having invested in there.

After the hearings, Sinatra penned an op-ed, published in the New York Times on July 24, in which he questioned how “a convicted murderer was allowed to throw my name around with abandon, while the TV cameras rolled on.” Sinatra compared it to the witch hunts of the McCarthy era, and felt he was unfairly targeted because of his Italian heritage. “If this sort of thing could happen to me,” he wrote, “it could happen to anyone.”

After those congressional hearings, the shuttered racetrack faded from people’s memories. It was saddled by financial problems throughout its brief existence. By the end of 1963, it had gone into foreclosure and was put up for auction. The track went bankrupt again in 1964.

On July 2, 1969, the Massachusetts Racing Commissioner announced that Berkshire Downs canceled its season because of “extensive and persistent losses from 1964 to date.”

In the 1970s, the track occasionally hosted a handful of racing dates, but for the most part, the track was defunct. “Berkshire Downs has been a blotch and a stigma on our county ever since it was built,” said State Senator John H. Fitzpatrick, referring to the track’s alleged underworld connections.

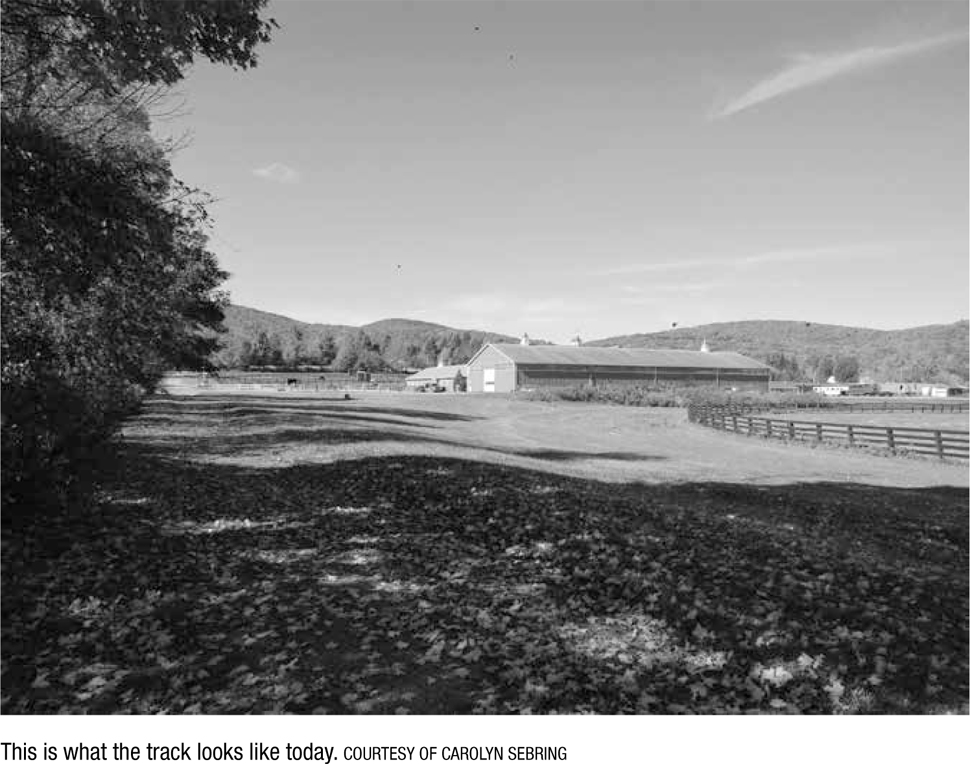

Today, the town of Hancock has just over 700 residents. The racetrack property is owned by the Rabouin family, and since 2000 it has been home to Sebring Stables. Morgan horses are bred and trained there. The grandstand is long gone, but the 0.5-mile track remains.

Carolyn Sebring said she was not aware of the storied history before she moved there, but has enjoyed hearing people share their memories about the place. “Everyone has wonderful stories that they tell, about going to the track with their uncle, or grandparents,” she said. “It’s a great facility, especially because the track is still intact.”