AT THE BATTLE FRONT

Late Spring 1863

When Fred woke up the morning of May 1, his father was not in the cabin the two of them shared belowdecks, nor could Fred find him anywhere on the ship. General Lorenzo Thomas, who was in charge, told him that Grant had gone to Port Gibson, eight miles away, and that “I was to remain where I was until he came back.” That was an order. Fred could get no more information from him.

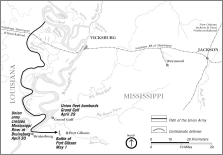

The Union army was now on Mississippi soil, twenty miles south of Vicksburg. The first thing Grant wanted to do was to secure the river coast for the Federals by seizing control of Grand Gulf and Port Gibson, both Confederate strongholds. Two days earlier, on April 29, Admiral Porter’s ironclads had tried to take Grand Gulf but had failed. As Fred now knew, today his father was attacking Port Gibson.

Fred stood at the ship’s railing, watching all the activity around him. Onshore he saw troops preparing to march in the direction of the cannon fire he could hear in the distance.

He knew what he had to do. He respected his father, and he strived to be a good soldier and obey orders. But he could not wait out the battle here onboard ship. He had to go.

Porter’s ships, now successfully downstream from Vicksburg, transported Grants army across the Mississippi River at Bruinsburg on April 30. The following day Grant attacked the Confederates at Port Gibson.

He saw his chance when a rabbit onshore caught his eye. All innocence, “I asked General Thomas to let me go ashore and catch the rabbit.”

The unsuspecting Thomas gave permission, and moments later Fred was onshore and running. He caught up to a wagon train and was able to ride one of the mules for a while before marching with an artillery group and then a regiment. The whole time the sounds of battle were coming closer.

Fred didn’t describe what happened next, but soldiers often felt overwhelmed and confused by their first taste of battle. Fred may have been momentarily deafened by the roar of cannon, or even knocked to his knees when the ground shook from the thunderous blasts. It is hard to imagine what he must have felt as the air became hazy with smoke and he heard the sounds of gunfire and the shouts and cries of his comrades, some falling under fire.

He did report that he eventually spotted his father on his horse watching the unfolding scene. He wanted to go to him, he recalled, but “my guilty conscience so troubled me that I hid from his sight behind a tree.”

When he thought it was not possible for the battle to last another minute, the Union troops, who greatly outnumbered the Rebels, finally got the upper hand. As they rushed forward, the sun already beginning to set, Fred joined the shouts of “Hurrah!” for “the enemy had given way.”

He ran onto the battlefield among the exhausted, jubilant men, cheering, but as the celebration began to die down and he looked around, he was suddenly sobered. Fallen soldiers were everywhere, some dead, some dying, many begging for help. This would not have been his first time seeing casualties: two days earlier, after the battle for Grand Gulf, he had seen sailors on the ironclads who had been killed or injured and it had sickened him. Now, at Port Gibson, “the horrors of a battlefield were brought vividly before me,” he said. “Night came on and I walked among our men in the moonlight.” Though dazed, he realized that all about him, soldiers who were uninjured were helping with the dead and wounded. “I followed four soldiers who were carrying a dead man in a blanket. They put the body down a slope of a little hill among a dozen other bodies. The sight made me faint… and I hurried on.”

Doctors and nurses traveled with the armies to care for the wounded at field hospitals like this one behind Union lines.

Wanting to help, he joined a detachment that was transporting the wounded to a schoolhouse that served as a field hospital. He was unprepared for what he saw next. “Surgeons were tossing amputated arms and legs out of the windows. The yard of the schoolhouse was filled with wounded and groaning men who were waiting for the surgeons.”

Twelve-year-old Fred could take no more. “I picked my way among them to the side of the road and sat on the roots of a tree. I was hungry, thirsty and worn out, and, worse than all, I didn’t know if my father were living or dead. No boy was ever more utterly wretched.”

Then a man on horseback stopped and looked down at him, exclaiming, “Why, hello, is that really you?” It was one of his father’s officers, and Fred was greatly relieved to see him. “Dismounting, he proceeded to make me comfortable, putting down his saddle for a pillow, and advising me to go to sleep. This I did, but my sleep was broken by dreams of the horrors I had witnessed.”

Later, the officer awoke him to tell him General Grant had arrived. Through exhausted eyes, Fred looked where the officer pointed. “About fifty yards off sat my father, drinking coffee from a tin cup. I went to him, and was greeted with an exclamation of surprise, as he supposed I was still on board the boat.”

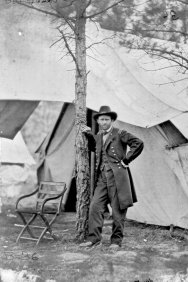

Though he commanded an army, Grant shared the same living conditions as ordinary soldiers.

Grant was direct. “How did you get here?”

“I walked,” Fred confessed, certain he was in trouble. But his father surprised him. “He looked at me for a moment, and then said, ‘I guess you will do.’ And there was no anger in his face. Maybe I was mistaken, but I half believed he was not sorry that I left the gunboat.”

The next morning, as the army broke camp, he managed to find a horse to ride. It had no harness, but he was able to make one from some rope he found on the ground. All day he followed the troops. His father had gone somewhere else, and he was on his own. When the troops stopped for the night, he sought shelter at a house “where some officers were sleeping on a porch. I crawled in for a nap between two of them.” The next day when he joined his father, Grant noticed that Fred’s horse was lame. “Father, who was ever kind and thoughtful, insisted that I should take his mount.”

During the next week, Grant was able to claim another victory, for Federal troops took possession of Grand Gulf when retreating Confederates abandoned it after their loss at Port Gibson. One day, while the Union army rested, Fred and a young orderly were exploring some of the countryside when they saw a house with a dozen horses tied up in front. Hoping for some glory, “we conceived the idea of capturing the mounts, and possibly the riders also, who were inside the house. Not until we had gone too far to retreat did the idea occur to us that the would-be captors might possibly become the captured.

“It was with great relief that we saw a man wearing a blue uniform come out of the house, and we then discovered that the party we had proposed to capture was a detachment of Sherman’s signal corps.”

A WEEK LATER, the army started moving northeast toward the state capital of Jackson, sixty miles away. Grant’s plan was to defeat Confederate general Joe Johnston, whose army occupied the city, so Johnston couldn’t help defend Vicksburg. Once Grant was in control of Jackson, he would march his army back west toward Vicksburg, taking advantage of the good road that stretched the forty miles between the two cities.

The Mississippi weather slowed the troops as they moved toward Jackson. It rained every day, soaking the men as they trudged along muddy roads. Wagons got stuck, and fires were hard to start and harder to keep going. So his army could move more quickly, Grant had brought along only basic supplies. He had learned early on that food was abundant enough in the agricultural South that his army could live off the land-or at least it could while plantations were still intact and fully stocked. That was changing. But on the march to Jackson he expected the men to scavenge for food. Fred found meals with his father to be so irregular that “I, for one, did not propose to put up with such living, and I took my meals with the soldiers, who did a little foraging, and thereby set an infinitely better table than their commanding general. My father’s table at this time was, I must frankly say, the worst I ever saw or partook of.”

Grant defeated the Confederates at Raymond on May 12 before marching on to Jackson.

General Grant slept on the ground with his men, “without a tent, in the midst of his soldiers, with his saddle for a pillow and without even an overcoat for covering,” according to a newspaper reporter traveling with the troops. The reporter went on to write, “More than one night, I bivouacked on the ground in the rain after being all day in my saddle. The most comfortable night I had, in fact, was in a church of which the officers had taken possession. Having no pillow, I went up to the pulpit and borrowed the Bible for the night.”

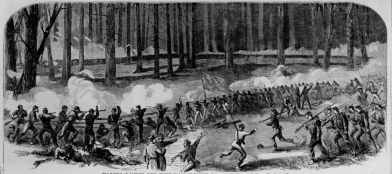

Grant was certain he wouldn’t make it all the way to Jackson without a challenge from the Rebels. It came on May 12 when advance Union troops approached Raymond, Mississippi. The Confederates were waiting for them and opened fire. Neither side knew the size of the opposing force, though it would gradually become clear that the Rebels, with 3,000 men, were outnumbered three to one. The fighting was savage. Sometimes the two sides were so close to each other, they used their guns as clubs because it was too crowded to aim and shoot.

Because of all the smoke and dust, commanders on both sides had problems sizing up each other at the Battle of Raymond.

More Federal troops arrived, but the Confederates held on. Finally, badly outnumbered, they fell back through the little town of Raymond. It was raining. Women in the town were caring for wounded men, protecting them from the rain with quilts they had brought from home. In anticipation of a Confederate victory, they had also fixed a grand meal for their soldiers. But hungry as they were, the retreating Rebels dared not stop to eat. Instead, the Yankees pursuing them stopped just long enough to gulp down the food.

Fred was not at the Battle of Raymond, but he arrived there the next day with his father, “and here again I saw the horrors of war, the wounded and the unburied dead.” He no longer had any illusions about the grandiosity of war: the price the men paid was terrible.

Though the rain never let up, the Union army resumed its march toward Jackson. Bands of Rebel guerrillas dogged them, their sharpshooters keeping Union soldiers on edge. Both Grant and Sherman fought in skirmishes, often leading the action. Fred remembered one incident when “the enemy’s sharpshooters opened fire on us. One of the staff shouted to my father that they were aiming at him. His answer was to turn his horse and dash into the woods in the direction whence the bullets were coming.” Grant’s staff quickly followed, and together they pushed back the Rebels.

Rebel guerrillas, like this legendary group known as Mosby’s Raiders, bedeviled Union troops as they moved through the South.

When the army finally reached the outskirts of Jackson, Fred left his father’s side and pressed ahead on his own. He hoped to take possession of the Rebel flag flying from the state capitol and keep it as a souvenir. “Confederate troops passed me in their retreat,” he said. “Though I wore a blue uniform, I was so splashed with mud, and looked generally so unattractive, that the Confederates paid no attention to me.”

In pounding rain, Fred rode into the city and encountered “a mounted officer with a Union flag advancing toward the capitol.” Fred followed. When he saw the capitol building, he raced ahead into its now-deserted halls, intent on only one thing. But he was too late-another Union soldier had already claimed the prized Rebel flag. Still, he proudly stood at attention when the American flag was raised above the building to take its place, and he was there to greet his father when Grant later rode into town.

Arriving Union troops had expected a fight from General Joe Johnston and his Confederate army. But Johnston had fled and it took only five hours on May 14 for the Union bluecoats to spread out and occupy the city, fighting small groups of holdout insurgents as they went. Grant ordered Sherman to destroy anything that could contribute to the Confederate cause. As a result, much of the city was burned to the ground. Fred was with General Sherman and said, “I saw the match put to the stores of baled cotton, at my father’s order.”

With factories and warehouses destroyed and the rail lines cut, Grant had struck a severe blow to Mississippi’s war effort. He was now between the armies of the Confederate generals Joe Johnston and John Pemberton, and he was on solid land, only forty miles from Vicksburg. All that remained was to march west and take the city. Then, finally, he could silence the cannon guarding the river and bring that great waterway under Union control.

Before fleeing the city, General Johnston had been quartered in the best room at the Bowman House, Jackson’s finest hotel. That night of May 14, after two weeks on the road, General Grant slept in a bed at last-the very one Joe Johnston had occupied the night before.

When Grant and Sherman entered Jackson, they stopped at a textile mill. Grant allowed the workers time to gather their belongings and then burned the mill.