THE ROAD TO VICKSBURG

May 15-19, 1863

On May 15, Grant and most of his army departed Jackson, leaving the city in flames. Fred rode with his father. Everyone was tense, uncertain of what lay before them on the road to Vicksburg. The constant rain, the muddy roads, and the harsh hot sun slowed Grant’s army. Northerners who had been in Mississippi since the beginning of Grant’s campaign were becoming toughened to the heat and humidity, but newer troops, used to cool breezes, struggled to keep up.

The army stopped for the night, then was on the road early the next morning when spies confirmed that Pemberton was moving eastward toward them with 22,000 men. Grant, heading west, had 30,000 men. Even with greater troop strength, he expected a tough fight against Pemberton. They had served together in the Mexican War, and Grant knew that Pemberton was smart, strong, and disciplined. “This I thought of all the time he was in Vicksburg and I outside of it; and I knew he would hold on to the last,” Grant later wrote.

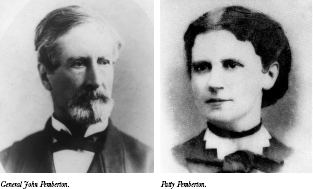

Pemberton also knew a hard fight was ahead. His spies had reported Grant’s troop strength, and he immediately regretted having left 10,000 of his men behind in Vicksburg—something he had to do in case the Yankees attacked from the river. He had expected to meet up with General Joe Johnston and merge their two armies, knowing that together they would outnumber the Federals. But where was Old Joe? Pemberton had received no word from him since Johnston had abandoned Jackson several days earlier.

Pemberton had other problems as well. He and his generals disagreed on strategy for the upcoming battle. Also, because Pemberton was a Northerner, some of the troops did not trust his leadership. He was from Philadelphia, and two of his brothers were Union officers. His wealthy family had disowned him when he decided to fight for the South—a decision influenced by his beautiful young wife, Patty, who was from Virginia and was passionately pro-Confederate.

Fortunately for Pemberton, all his generals and their men were united in their determination to beat the Yankees, even if they had to do it without Joe Johnston’s help.

On May 16, Grant’s and Pemberton’s armies met halfway between Jackson and Vicksburg on a farm belonging to the Champion family and began lining up opposite each other. The land included a high hill that became the center of what would be known as the Battle of Champion’s Hill—the fiercest and most bloody battle of the Vicksburg campaign.

In the bloody Battle of Champion’s Hill, when soldiers ran out of ammunition, they fixed their bayonets and charged.

On that morning, Grant was in high spirits, confident the day would end in victory. He called out to his men that this was the day they would fight the battle that would win Vicksburg. On a signal from officers, the battle began. Cannon roared their opening volleys and the two sides charged each other, then regrouped and charged again. Generals usually stayed far enough behind the front lines to be out of the range of fire, but on this day Grant stayed close to the men, riding up and down the lines on his horse, shouting orders, and encouraging and inspiring his troops.

Fred witnessed his father’s bravery during a crucial moment. “Our line broke and was falling back when Father moved forward and rallied the men. He rode to all parts of the field, giving orders to the generals, and dispatching his staff in all directions.” Appreciative soldiers fought hard for their commander. Many later reported seeing him on the battlefield, and several commented on his humbleness and his encouragement to the men, who always cheered when they saw him.

Both sides gave their all. When they were the attackers, the Confederates often employed their famed Rebel yell, meant to terrorize the bluecoats. One Union soldier described it as sounding like 10,000 starving and howling wolves.

Pemberton and his officers kept watching for Joe Johnston to join the battle, but Johnston didn’t come. Finally, after a long and bloody day, the Union, with its superior numbers, forced the Confederates to withdraw in defeat.

NIGHT FELL. Bill Aspinwall, a Union soldier, had fought hard all day. He had been shot in the shoulder but could not get medical assistance because his injury was light compared to so many others. In pain and too exhausted to do anything more, he bedded down on a corner of the battlefield. Nearby lay a Confederate soldier who was severely wounded. Feeling sorry for him, Aspinwall offered to share his blanket, and the soldier accepted. Though they had fought against each other hours before, now they lay under the stars and talked. The Confederate was growing weaker. Fearful he would die, he gave Aspinwall a card with the address and names of his wife and children and asked him to let his family know what had happened to him. Aspinwall promised he would. He drifted off to sleep, and when he awoke, the Confederate was dead.

Aspinwall couldn’t write because of his shoulder injury, but he found another soldier who penned a letter to the Confederate’s wife. Then he made his way to a Confederate field hospital and gave the letter to an officer, who thanked him and said he would see that it was delivered.

Such acts of kindness were not uncommon. Grant later wrote, “While a battle is raging one can see his enemy mowed down by the thousand, or the ten thousand, with great composure; but after the battle these scenes are distressing, and one is naturally disposed to do as much to alleviate the suffering of an enemy as a friend.”

It had been a terrible day on both sides, with a combined estimate of over 8,000 men dead. In describing the Battle of Champion’s Hill, one soldier commented, “We killed each other as fast as we could.”

ALL THAT NIGHT AFTER THE BATTLE, Pemberton’s defeated soldiers retreated toward Vicksburg. When they got to the Big Black River bridge, twelve miles from the city, most of the army crossed on over. Because the hour was so late, the last 5,000 men, exhausted from their grueling day of battle, bedded down next to the river and slept behind a barricade of cotton bales. Many of them were injured, and all of them were demoralized. They were startled awake early the next morning to cries of alarm. As they pulled themselves to their feet, they learned that the Yankees had pursued them and were preparing to attack.

With their backs to the river, 5,000 Rebels faced 17,000 Federals. Suddenly, without waiting for anyone else, one of Grant’s officers gave the signal for his division to advance, and 1,500 Yankee bluecoats, their bayonets ready, surged forward across a field and through the waist-high water of a bayou, then charged directly into the Confederate lines.

The mayhem lasted only three minutes. Overwhelmed, the retreating Rebels swarmed across the Big Black’s bridge. Those who could not get to the bridge tried to swim the river, and many drowned. Another 1,700 were killed or captured before the Confederates could finally set fire to the bridge to stop the Yankee pursuit.

Fred was there and saw it all. When the Union troops charged the Confederate line, he recalled, “I became enthused with the spirit of the occasion, galloped across a cotton field, and went over the enemy’s works with our men.”

Fred was thrilled. The Confederates were in retreat. They were on the run! But at that very moment, as he savored this victory, his luck ran out. “Following the retreating Confederates to the Big Black, I was watching some of them swim the river,” he recalled, “when a sharpshooter on the opposite bank fired at me and hit me in the leg.”

With a cry of shock and pain, Fred fell to the ground. His leg was bleeding. Was this how his life would end? Bleeding to death on a battlefield? A moment later, one of Grant’s aides “came dashing up and asked what was the matter. I promptly said, ‘I am killed!’ Perhaps because I was only a boy, the colonel presumed to doubt my word and said, ‘Move your toes,’ which I did with success.

“He then recommended our hasty retreat. This we accomplished in good order.”

PEMBERTON’S BEATEN ARMY struggled back to Vicksburg with less than half of the 22,000 soldiers that had set out days earlier to meet the Yankees. At the Big Black River, Grant and Sherman put part of their men to work constructing three temporary bridges to replace the bridge the Confederates had burned. Other soldiers foraged for food and looted homes in the area. Sherman stopped to drink water from a well near a log cabin and learned that the property belonged to Jefferson Davis. The house had been plundered by his troops, and Sherman found a book on the ground that was a copy of the United States Constitution. It would become a prized souvenir, for he noticed to his amazement that on the title page was written the name of the owner: Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederacy.

That night, when the bridges were complete, Grant’s army began to move across the river. Sherman, an amateur artist, viewed the scene with a painter’s eye. He wrote, “After dark, the whole scene was lit up with fires of pitch-pine. General Grant joined me there, as we sat on a log, looking at the passage of the troops by the lights of those fires; the bridge swayed to and fro under the passing feet, and made a fine war picture.”

Fred’s leg was attended to by a physician who removed the bullet and dressed the wound. Fred knew such an injury could be fatal if it became infected. The next day, he was still shaken from his experience and in pain from the wound, but he rode with his father and Sherman all the way to the bluffs north of Vicksburg. In the distance they could see the Mississippi River.

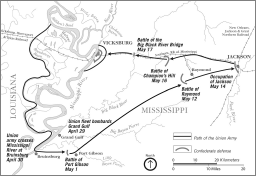

Grant felt Vicksburg was as good as taken. Very quickly he would silence the guns along the water, and the great Mississippi River would be completely in Federal hands. How could anyone doubt it? He had successfully transported his army south of Vicksburg. In the last eighteen days he had marched his men 200 miles into enemy territory and won five battles:

After Confederates burned the bridge over the Big Black River, Sherman’s engineers constructed a pontoon bridge similar to this one on the James River in Virginia.

Grant’s successes at Champion’s Hill and the Big Black River put him in position to attack Vicksburg only eighteen days after getting his army onto Mississippi soil.

Grand Gulf, Port Gibson, Raymond, Champion’s Hill, and the Big Black. He had defeated Pemberton, badly damaging and demoralizing the Rebel army.

As they gazed at the river on May 19, Sherman shook his head with amazement. He knew that what Grant had already accomplished would go down in military history as nothing short of brilliant.

“Until this moment,” he said to his old friend, “I never thought your expedition a success. I never could see the end clearly until now.”