INTO THE CAVES

Late May and Early June 1863

As happy as Willie and his sisters were to be back in Vicksburg with their beloved father, the little city was a dangerous place. Dr. Lord impressed on his son that this was not a story from Ivanhoe or one of his other treasured adventure novels: the family was in real danger. Since May 18, Grant’s army had formed a tight ring around Vicksburg, sealing it from the outside world. The city was under siege, and, as one soldier said, a cat could not slip out unnoticed.

Grant wanted the siege to end quickly, before Joe Johnston showed up. To hasten Vicksburg’s surrender, he ordered his artillery units to shell it around the clock. The army aimed 220 cannon at military targets in the city and at the Confederate lines. Admiral Porter’s navy aimed another thirteen big guns from the river. Shells flew fast and furious, sometimes crisscrossing in the air as they rained down death and destruction on the city and the Rebel soldiers. Cannonballs weighing as much as 250 pounds crashed through walls, tore up streets and yards, and exploded in the Confederate trenches. Highly skilled Union sharpshooters loaded their rifles with minié balls—powerful and precise bullets that could travel long distances and kill or maim in an instant. Thunderous explosions and the z-z-z-z-z-z-pt sound of these deadly bullets whizzing through the air terrorized both humans and animals. Like their elders, children quickly learned that their best chance of survival was to try to dodge minié balls. They should never try to outrun cannonballs, but stop and let them fly on over.

This house, behind Union lines and badly damaged by shells, belonged to the Shirley family, who were Union sympathizers. Soldiers who camped in the yard created dugouts for shelter.

The Lord family soon found out that their home could not protect them. Willie’s sister Lida reported that while the family was eating dinner, “a bombshell burst into the very center of the dining room, blowing out the roof and one side, crushing the well-spread table like an eggshell, and making a great yawning hole in the floor, into which disappeared our supper, china, and furniture.”

Margaret Lord did not want to live in a cave, but after this incident her husband insisted. The family moved into a large communal cave that had been dug all the way through a hill. People could enter on one street and exit onto another. Off the long hallway was a series of rooms, each with an outside entrance. Willie compared this layout to the prongs of a garden rake. He said there were many outside entrances so if “any one of them should collapse, escape could be made through the inner cave and its other branches.” Entrances also gave fresh air, for the caves were otherwise hot and airless. Each of the rooms provided quarters for a family. The only privacy came from hanging blankets or setting up screens. Some house slaves slept in their family’s quarters, while others slept near the entrances, as did soldiers recuperating from injuries. The rest of the hallway became a “commons.” In this space, Willie said, “children played while their mothers sewed by candlelight or gossiped, and men fresh from trench or hospital gave news of the troubled outside world to spellbound listeners.”

Townspeople tried to make their caves comfortable. Sometimes prayer helped ease worry and fear.

This cave, one of the largest in Vicksburg, was only one of an estimated 500 that dotted the city by the second week of the siege. There were so many caves that Union soldiers jokingly referred to the city as Prairie Dog Town. Some caves were very small—just a dugout where people huddled for protection. Some had clusters of rooms and were elaborately decorated with carpets, mirrors, furniture, and beds. Townspeople brought their pillows and favorite quilts, musical instruments, china, and silver, and they hung pictures and built shelves to hold treasured photos, beloved books, and knickknacks or vases of flowers from their home gardens. Planks were laid on the ground to create flooring. Doorways were framed with wood, and walls were covered with rugs, pictures, or even wallpaper to give an illusion of cleanliness.

Outside, many people set up tents near cave entrances to shelter the cooking and eating area from sun and rain and to provide private places to dress. Because of the fire hazard, cooking had to be done in open air. During brief interludes each morning and evening when the shelling slowed or stopped, slaves labored over fires and cooking stoves to prepare meals for their masters. If they heard incoming shells, they ran into the caves.

As hard as people worked to make the caves comfortable, they were still dark and damp and home to lizards, mosquitoes, and other insects. Several days of heavy rains turned everything to mud. “It was living like plant roots,” one woman reported. “We were in hourly dread of snakes. The vines and thickets were full of them, and a large rattlesnake was found one morning under a mattress on which some of us had slept all night.”

At first Willie loved cave life, thinking of it as “the Arabian Nights made real. Ali Baba’s forty thieves … lurked in the unexplored regions of the dimly lighted caves … and sent me off at night to fairyland on a magic rug.” But he worried when his father left each morning to go to work “and we only knew him to be safe when he returned at night.” He also grew tired of “squalling infants, family quarrels and the noise of general discord that were heard at intervals with equal distinctness.” Not surprisingly, his mother had the hardest time. She implored her husband to have a cave dug for their private use. Dr. Lord gave in and agreed to see to it.

One of the other families living in this very large cave was Lucy’s. Her father refused to leave the family home, even though, Lucy reported, “a Minie ball passed through his whiskers as he sat in the hall, and lodged in the rocker of an old chair near him.” Still, her mother couldn’t budge him, so she had Rice and Mary Ann pack up necessities and she moved the rest of the family into the communal cave. Lucy thought there must have been about 200 people sharing this space, counting all the slaves and the recuperating soldiers. Class status disappeared. Poor whites slept next to wealthy plantation owners, and slaves slept next to their masters.

No one knew if they were actually safe. One night Lucy found out. She had stretched out on her bed—a wood plank covered with soft quilts—but couldn’t get to sleep. She listened to the sounds around her. Outside, shells crashed and exploded. In a nearby room a young wife was in labor and would soon give birth. Finally Lucy got up and wandered into the main hallway. Several adults sat visiting by candlelight. One of them was Dr. Lord, who had a sore leg and foot. As Lucy later recalled, he was “all bandaged and propped on a chair for comfort. He said, ‘Come here, Lucy, and lie down on this plank.’ Dr. Lord was almost helpless, but he assisted me to arrange my bed, my head being just at his feet.”

Lucy was finally drifting off to sleep when “suddenly a shell came down on the top of the hill, buried itself about six feet in the earth, and exploded. This caused a large mass of earth to slide … catching me under it. Dr. Lord, whose leg was caught and held by it, gave the alarm that a child was buried. Mother reached me first.”

Lucy’s frantic mother, assisted by Dr. Lord, “succeeded in getting my head out… [and] as soon as the men could get to me, they pulled me from under the mass of earth.” Lucy was terrified, screaming and choking as she hemorrhaged blood from her mouth and nose. Her mother implored the physician attending the young wife in labor to examine Lucy, and he gave assurance that she had no broken bones “but he could not then tell what my internal injuries were.”

At this very moment, a thunderous explosion shook the cave and Lucy watched as people became “frightened, rushing into the street screaming, and thinking that the cave was falling in. Just as they reached the street,over came another shell bursting just above them, and they rushed into the cave again.”

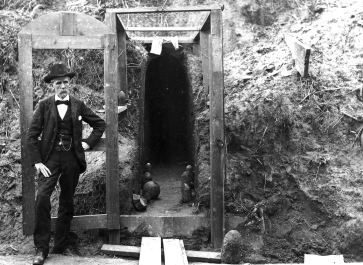

This photograph, taken after the war, shows an entrance to one of the caves. The cannonballs on display may have fallen nearby during the siege.

Unbelievably, Lucy reported, “during all this excitement there was a little baby boy born … He was called William Siege Green.”

WHEN ANOTHER SHELL STRUCK one of the cave entrances the next morning, Lucy’s mother declared that she’d had enough. “Mother instantly decided to leave the cave,” Lucy said, “and calling Rice and Mary Ann, she gathered clothing and bedding, determined to risk her life at home with Father. We left the cave about eight o’clock in the morning, having some distance to go to reach home. I was bent over from my injuries and could not run fast.”

The little group finally reached its goal. “Father was horrified when he saw us,” Lucy said, “and immediately made an effort to secure us another hiding place.” Very quickly Mr. McRae located a cave closer to home and also deeper in the earth, making it safer. “A number of steps led down into this cave,” Lucy remembered. “Mother had a tent pitched outside, so that when the mortars did not have the range we could sit there and watch the shells as they came over. They were beautiful at night.”

Shortly after the McRaes left the communal cave, the Lord family experienced another fright there when one of the entrances suddenly collapsed. Willie wrote, “My father’s powerful voice, audible above the roaring avalanche of earth as he shouted, ‘All right! Nobody hurt,’ quickly reassured us. But after these narrow escapes there was no longer a feeling of security even in the more deeply excavated portions of the cave.”

Dr. Lord rushed the completion of the cave being dug for his family’s private use by helping with the work. He had selected a location in a hill behind one of the hospitals, reasoning that “here, under the shadow of the yellow hospital flag which … was held sacred by all gunners in modern warfare, it was believed we should be comparatively safe.” But eleven-year-old Willie quickly realized that shells were falling everywhere, including on the hospital. Another Vicksburg hospital took a direct hit from a shell, killing eight and wounding fourteen. A surgeon buried under the rubble saved himself from bleeding to death by tying off an artery. His leg was later amputated. In spite of the constant danger, the women of Vicksburg continued to volunteer in the hospitals.

Willie’s mother and youngest sister had a very close call one day when two large shells fell nearby and exploded simultaneously, filling the air with flames and smoke. Willie’s mother tried to soothe her four-year-old daughter, saying, “Don’t cry, my darling. God will protect us.” To which the girl replied that she was afraid that God had already been killed.

In spite of the danger, Margaret Lord was much happier in this private cave, which was shaped like the letter L and had two entrances, allowing some circulation of air inside. She wrote, “In this cave we sleep and live literally under ground. I have a little closet dug for provisions, and niches for flowers, lights and books. Just by the little walk is our eating table with an arbor over it, and back of that our fireplace and kitchen with table … This is quite picturesque and attractive to look at but Oh! How wearisome to live!”

Her children, she said, “bear themselves like little heroes.” Her husband also did his part. Every day Dr. Lord opened Christ Episcopal Church and, according to Willie, he “rang the bell, robed himself in priestly garb, and … with the deep boom of cannon taking the place of organ notes and the shells of the besieging fleet bursting around the sacred edifice, he preached the gospel of eternal peace.”

With his ability to calm, Dr. Lord served as comfort to the townspeople and soldiers who risked shells and bullets to attend his services. During the first few weeks of the siege, Emma Balfour often attended Dr. Lord’s services and noted in her diary, “The church has been considerably damaged and was so filled with bricks, mortar and glass that it was difficult to find a place to sit.” The Catholic church continued to host daily mass. The few churches that remained open usually had people sleeping in their pews at night because they felt safer there than in caves.

EMMA BALFOUR STILL REFUSED to move her household into a cave. She took shelter in one when the shelling was heavy, but she always felt like she was suffocating when she was underground. At home, she kept an eye on the river, concerned that the Federals would launch an all-out attack. Sometimes she and a friend or two would brave the shelling and go to Sky Parlor Hill for a better view. Ten days into the siege, she had seen the sinking of a Union gunboat, the Cincinnati, considered one of the finest in the Union fleet, when it was hit by the Vicksburg waterfront cannon. “We are again victorious on water!” she had declared. A Confederate soldier said that hundreds of women watched from Sky Parlor Hill. “There were loud cheers, the waving of handkerchiefs, amid general exultation, as the vessel went down,” he said.

As the siege wore on, some Union soldiers expressed concern for the townspeople. They did not take lightly to starving and shelling old people, women, and children. One soldier said, “I can’t pity the rebels themselves but it does seem too bad for the women and children in the city.” Another wrote, “I suppose [the women] are determined to brave it out. Their sacrifices and privations are worthy of a better cause, and were they but on our side, how we would worship them.”

Emma surmised why the Federals bombarded Vicksburg so ruthlessly. “The general impression is that they fire at this city, in that way thinking that they will wear out the women and children and sick, and General Pemberton will be impatient to surrender the place on that account, but they little know the spirit of the Vicksburg women and children if they expect this.

“Rather than let them know that they are causing us any suffering, I would be content to suffer martyrdom!”