CHAPTER 10

ASTHMA

BARBARA BENAGH’S influences are diverse. She studied Iyengar yoga in the 1970s and 1980s, and later trained intensively with yoga teacher Angela Farmer. Her interest in using yoga for asthma was sparked by her own problems with the disease, including frequent pneumonias and many hospital stays, including a near-fatal incident requiring admission to intensive care. It was after that ICU stay that she dedicated herself to learning all she could about breathing. She was inspired by the work of Dr. Gay Hendricks, author of Conscious Breathing, and Dr. Konstantin Buteyko, a pioneer in the use of breath retraining for people with asthma. Her experience with yoga told her that “If I persevere, and I continue to work, I will eventually find things to help me.” After much trial and error she hit upon a series of exercises that slowly transformed her entire relationship with breathing. By a few years ago, she’d improved so much that she was even able to return to a passion she’d had to drop ten years earlier: long-distance bicycling. Barbara has been teaching yoga in the Boston area and internationally for more than thirty years.

BARBARA BENAGH’S influences are diverse. She studied Iyengar yoga in the 1970s and 1980s, and later trained intensively with yoga teacher Angela Farmer. Her interest in using yoga for asthma was sparked by her own problems with the disease, including frequent pneumonias and many hospital stays, including a near-fatal incident requiring admission to intensive care. It was after that ICU stay that she dedicated herself to learning all she could about breathing. She was inspired by the work of Dr. Gay Hendricks, author of Conscious Breathing, and Dr. Konstantin Buteyko, a pioneer in the use of breath retraining for people with asthma. Her experience with yoga told her that “If I persevere, and I continue to work, I will eventually find things to help me.” After much trial and error she hit upon a series of exercises that slowly transformed her entire relationship with breathing. By a few years ago, she’d improved so much that she was even able to return to a passion she’d had to drop ten years earlier: long-distance bicycling. Barbara has been teaching yoga in the Boston area and internationally for more than thirty years.

Ken Paul figures he’s been an asthmatic for fifty-four years, ever since he was about two. Because his doctors misread his symptoms for years, however, he didn’t know what was wrong with him until sometime in his twenties, when he visited family in Ireland. By that time, Ken had already had pneumonia five times, and had been hospitalized on several occasions. His brother-in-law, a pulmonary specialist there, told him he clearly had asthma and introduced Ken to Cromolyn, an inhaler that was not yet available in the US. Back in Boston his doctors eventually put him on Azmacort, an inhaled steroid, which he remained on for years. Even though inhaled steroids kept his condition under control, and his doctors had no qualms about prescribing them, Ken was concerned about the effects of the medication being absorbed into his system, and he wanted to learn about possible alternatives, including yoga.

Ken began to study yoga twelve years ago, and has had a daily home practice for the last ten. At a friend’s suggestion, he also started taking a regular class with a Kripalu teacher, which he enjoys. While helpful in many ways, however, his asana practice hadn’t resolved his breathing troubles. He got more serious about wanting to address his asthma after reading an article Barbara Benagh had written in Yoga Journal about her path to recovery after having almost died of asthma. He identified closely with the experience. “I’ve had some episodes, especially with the pneumonias and some of the bronchitises, when I wasn’t sure I was going to make it.” He figured that trying out the breathing exercises and other ideas Barbara wrote about in the article was worth doing, since she had made such remarkable progress.

Overview of Asthma

Asthma is a condition in which the bronchial tubes in the lungs become swollen, constricted, and blocked with mucus secretions, causing the characteristic symptoms of wheezing, chest tightness, cough, and shortness of breath. It has been linked to genetic factors, allergies, and environmental conditions, though its causes vary from person to person. Asthma often begins in childhood, but can occur at any age. While some children seem to outgrow their asthma, if it begins in adulthood, it tends to be more persistent. For reasons that are not completely understood, the incidence and death rates from asthma have been rising dramatically in recent years. Air pollution, rising stress levels, and a lack of exposure to germs during childhood that may render the immune system hypervigilant have all been suggested as possible reasons.

The rising incidence of fatal asthma attacks may also be linked with bronchodilating medications. These bronchodilators—called beta-agonists because they stimulate the beta-receptors in the lungs—dilate constricted bronchial tubes, and when inhaled, can calm down asthma symptoms within minutes. It’s possible, however, to use these inhalers too often (when what is needed is stronger medication), temporarily suppressing symptoms that inevitably rebound. Worse, the bronchodilators may also mask an impending asthmatic crisis, causing a delay in getting emergency treatments, sometimes until it’s too late. Due to these problems and the increasing understanding of the role that inflammation plays in asthma (which beta-agonists do nothing to reverse), anti-inflammatory cortisone drugs (steroids), inhaled or in more severe cases oral, have become the gold standard of conventional treatment in all but the mildest cases.

How Yoga Fits In

From a yogic perspective, many people—and not just asthmatics—breathe in a dysfunctional and inefficient way (see Chapter 3). Improving their breathing patterns can increase oxygen supply to the tissues, lower stress levels, and induce muscular relaxation, good for everyone but potentially lifesaving for someone with asthma. Barbara Benagh sees a half dozen dysfunctional breathing habits in people with asthma (see box). Despite years of yoga, Barbara realized she had had almost all of these habits herself. “I wasn’t a diaphragmatic breather. I was a mouth breather, a breath holder, high-chest breather. I was like an asthma person waiting to happen. All it took was for me to catch pneumonia for it to be the final straw. I had everything already set up to go, and a lot of people do.”

COMMON DYSFUNCTIONAL BREATHING HABITS IN PEOPLE WITH ASTHMA

| 1. Chest Breathing | 4. Mouth Breathing |

| 2. Inhalations Stronger Than Exhalations | 5. “Reverse” Breathing |

| 3. Breath Holding | 6. Overbreathing |

Chest breathing means that most of the air goes into the upper and middle chest, and less goes to the lower portions of the lungs. Stress is one reason for chest breathing, and yogis believe further stress can be the result of breathing this way. Think of the way you breathe if you are startled—with a quick, shallow inhalation you can feel just below your collarbones. Some people with asthma breathe like this most of the time, and if you try it for a few breaths, you’ll see that doing so is agitating to the mind. Another result of chest breathing is that the lower areas of the lungs, richly supplied with blood vessels, don’t get enough oxygen to fully replenish the blood passing through those vessels.

A slumping posture, common in modern society (see Chapter 2), also contributes to chest breathing by pushing the lower ribs into the upper abdomen. This limits the movement of the diaphragm, the large dome-shaped sheet of muscle beneath the lungs, which ought to be the primary muscle of respiration, so the chest (and sometimes the neck) muscles take over. With chronic chest breathing, the diaphragm can become weak, just like any other muscle that doesn’t get enough exercise, exacerbating the problem. Chronic poor postural habits also can lead to tightness in such muscles as the pectoralis in the chest and the intercostals between the ribs, as well as in ligaments and connective tissue in the chest, all of which can limit the ability of the rib cage to fully expand and contract (see Chapter 13).

Most people with asthma have much more difficulty exhaling than inhaling, and the wheezing characteristic of the disease happens primarily on the out breath. Difficulty exhaling reflects the narrowing of small bronchial tubes due to inflammation, swelling, and bronchospasm (constriction of the bronchial tubes), as well as the accumulation of mucus in the airways. As the lungs expand on inhalation, traction is exerted on the airways, which opens them, but they tend to collapse as the lungs recoil on exhalation. Since the lungs take in too much air relative to the amount of air that is exhaled, stale air stays in the lungs, leaving less room for new oxygen-rich air to come in, thus compromising the oxygen supply to the rest of the body. In response, the breathing becomes quicker, and as we’ve seen, quick, small-volume breathing is both inefficient and stressful (see Chapter 3). From a yogic perspective, weakness of the abdominal muscles—and failure to engage them with exhalation—is an additional factor in difficulty breathing out.

Breath holding is the usually unconscious tendency to hold the breath after the inhalation. Pressure builds up, making it even harder to exhale in a relaxed fashion. This is stressful, and if done chronically, may put additional strain on the heart and lungs.

Mouth breathers inhale and exhale almost exclusively through the mouth. They tend to breathe more quickly, since the mouth offers less resistance to airflow than the nasal passages, and they lose the benefits of the nose’s warming, filtering, and humidifying of incoming air. (Cold air can be shocking to lungs, triggering bronchospasm, and fueling any inflammation that is already going on.) Mouth breathing also tends to dry out the mouth and throat, which can lead to further irritation in the airways.

In reverse breathing (paradoxical breathing), the diaphragm rises with inhalation and drops with exhalation, the opposite of normal. This reduces the efficiency of respiration and contributes to chest breathing, with all its disadvantages.

Overbreathing is the tendency to hyperventilate. Asthmatics often have abnormally high respiratory rates. If normal is twelve breaths per minute, they might breathe at two or more times that rate. They may take in plenty of oxygen, but at the expense of exhaling more carbon dioxide (CO2) than is healthy. With low levels of CO2 in the system, the pH of the blood rises (becomes more alkaline), and as a result, hemoglobin holds on to oxygen molecules more tightly than usual and the cells can’t get as much oxygen as they need. This can lead to a vicious cycle where the asthmatic breathes even faster to bring in more oxygen, blowing off even more CO2. Rapid breathing also tends to cool and dry out the respiratory passages, which can cause bronchospasm.

A number of yogic practices specifically address the six common breathing problems that Barbara outlined above. A number of breathing exercises, for example, strengthen the diaphragm and encourage its full excursion as it descends to bring air into the lungs. This so-called abdominal breathing is the opposite of chest breathing. A number of yogic practices, especially asana, systematically improve posture and with it the breath.

In yoga, you learn to engage the abdominal muscles as you exhale, squeezing additional air out of the lungs. This and improved posture allow more air to be taken in on the subsequent breath. Studies show that yoga can both increase lung capacity and the volume and efficiency of the exhalation (see Chapter 10).

By bringing awareness to your breathing through yoga, you learn to reduce unconscious breath holding. This new habit comes first during your yoga practice, but after you’ve practiced long enough, this and other beneficial breathing patterns tend to become your default mode, even when you are not thinking about it. Similarly, bad habits like mouth breathing and reverse breathing can be reduced and eventually eliminated by bringing awareness to the breathing process. The more dedicated and regular your yoga practice, the more effectively you’ll be able to replace dysfunctional breathing habits with the healthier ones you are practicing. For those who have difficulty breathing through the nose due to nasal allergies or a buildup of mucus, rinsing the nasal passages with salt water using a neti pot can open the passageways and remove allergens and inflammatory immune cells that can contribute to asthmatic symptoms (see Chapter 4).

Yoga counters the tendency to overbreathe by cultivating slow, deep, regular breaths. Once you’ve practiced yoga long enough, you start to realize that you can get more air in and out of your lungs with slow, mindful breaths, using as little effort as possible to move air, than by breathing rapidly. When your breath becomes labored, slow respirations calm your nervous system and help keep your mind less agitated. As some yogis with asthma will testify, sometimes the only way to move air during an attack is to breathe slowly and smoothly. Getting agitated will only worsen symptoms, causing a vicious cycle in which poor breathing leads to agitation, which makes the breathing even faster and more erratic.

Yoga can also help people with asthma by increasing their sensitivity to the state of their breathing. Many patients I’ve seen with asthma have gotten so accustomed to their limited breath capacity that they hardly notice it. Most are also completely unaware of their dysfunctional breathing patterns. As in all yoga therapy, recognizing the problem is the first step toward changing it. By tuning your awareness of your breathing in yoga you learn to become what Barbara calls a “breath detective.” One concrete advantage of greater sensitivity is that you may detect a flare-up of your asthma earlier in the process, when it’s easier to remedy and interventions are more effective.

Studying yourself—svadhyaya—can be facilitated by keeping a notebook where you track your asthmatic episodes, what foods you had eaten, how much sleep and exercise you had had, and any other factors that might have a bearing on your breathing. If your doctor has you measuring your peak flow rate (by using a small handheld device designed for that purpose) to monitor your breathing, or using other tests of your lung function, you should write those numbers down as well. Studies suggest, however, that monitoring symptoms may be just as valuable as monitoring peak flow rates. Yoga, because it sensitizes people to their breathing patterns, helps them become very good at gauging their symptoms.

Many yogis (and even some doctors) feel that stress plays a role in asthma, too. In addition to writing in a journal, talking to a psychotherapist or simply becoming more mindful of emotions as they arise—which a dedicated yoga practice helps you do—are also forms of svadhyaya.

A study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association demonstrated the usefulness of writing about emotional issues. Patients with chronic asthma were asked to write about the most stressful event of their lives for twenty minutes on three consecutive days. Patients in the control group were asked to write about an emotionally neutral topic, such as their plans for the coming day. Four months later, those who had written about the emotionally charged events showed a 20 percent improvement in their FEV1 (the maximum amount of air you can exhale in one second). There was no change in the lung function of the asthmatics who wrote about their plans.

I advocate writing in a stream-of-consciousness fashion for a short while every morning. Combined with yogic awareness, journal writing can be a wonderful complement to psychotherapy. And unlike therapy, which insurers don’t generally like to pay for anyway, the only expense is for the pen and paper. I particularly like a style of journaling known as “morning pages,” described in the book The Artist’s Way by Julia Cameron.

I advocate writing in a stream-of-consciousness fashion for a short while every morning. Combined with yogic awareness, journal writing can be a wonderful complement to psychotherapy. And unlike therapy, which insurers don’t generally like to pay for anyway, the only expense is for the pen and paper. I particularly like a style of journaling known as “morning pages,” described in the book The Artist’s Way by Julia Cameron.

Yogic Tool: MEDITATION. Perhaps more than any other yogic tool, meditation puts you in touch with subconscious thoughts and feelings that could be affecting your breathing. Stephen Cope, a psychotherapist and Kripalu yoga teacher, says, “I’ve noticed on long meditation retreats that almost all of my asthma symptoms resolve.”

The Scientific Evidence

A number of studies have examined the effectiveness of yoga for people with asthma. In 1967, the first clinical trial on yoga for asthma ever published was done by Dr. Mukund Bhole at the birthplace of the scientific investigation of yoga, the Kaivalyadhama ashram in Lonavla, India. In a later study there, Bhole and colleagues investigated the effects of a two-month program of various asana, breathing techniques, and yogic cleansing techniques (kriya) on fifty-five patients with asthma. They found that 40 percent had a good response, 33 percent a fair response, and 16 percent a slight response. It should be noted that their criteria were tough. A “good response” meant no attacks in the subsequent six months and no use of asthma medications for at least two months. A “fair response” was at least a 50 percent reduction in attacks with use of medication. A “slight response” meant the rate of attacks was reduced by 25 percent. When I met with Dr. Bhole, who is now semiretired, at his home in Lonavla, he told me that many of the patients they treated eventually relapsed, because once they felt better they stopped their yoga practice.

Dr. Virendra Singh and colleagues from the Nottingham City Hospital in England, in a study published in The Lancet, examined the effects of simulated pranayama in eighteen mildly asthmatic patients. The research subjects breathed through a device that slowed exhalation to twice the duration of inhalation (note the similarity of this procedure to the 1:2 breathing technique taught by Barbara later in the chapter). The control group used a similar device that did not restrict exhalation. The most significant finding was that it proved harder to provoke an asthmatic attack in the group who did the simulated pranayama when they were exposed to a chemical that can constrict the airways.

S. C. Jain and B. Talukdar, of India’s Central Research Institute for Yoga, studied forty-six adult asthmatics who took part in a forty-day residential program that included asana, pranayama, kriyas, and a vegetarian diet. Yoga training was associated with significant increases in FEV1, peak flow rates during exhalation, the amount of oxygen in the blood (both at rest and after exercise), and exercise capacity. Follow-up one year later was reported on thirty-one of forty-two patients who continued to practice fifteen to thirty minutes daily. Of these thirty-one, eighteen whose asthma was initially rated moderate to severe remained asymptomatic without medication.

A randomized controlled study, published in the British Medical Journal and conducted at the Swami Vivekananda Yoga Research Foundation near Bangalore, assessed the effects of an integrated yoga program which included asana, pranayama, yogic philosophy lectures, kriyas, and meditation. Drs. R. Nagarathna and H. R. Nagendra compared 53 asthmatics, ages nine to forty-seven, who underwent yoga training with 53 matched controls. Follow-up at fifty-four months included only the 28 patients who had continued to practice yoga at home at least sixteen times per month. These individuals showed significant improvement in peak flow, fewer attacks per week, and less need for medication. The same authors tracked 570 asthma patients who followed the same program over three to fifty-four months and found that approximately two-thirds were able to get off steroid drugs and other medications while demonstrating highly significant improvements in a number of measures of lung function and general health. Of note, those patients who continued to practice regularly showed the greatest improvements.

Not all yoga studies on asthma have shown clear-cut benefits. One showed small improvements in lung function that did not reach the level of statistical significance. Another found that a yoga group and a control group that did stretching exercises had improvements in symptoms and lung function, with no significant difference between the groups. A third study found no improvement in lung function, but showed a trend toward decreased use of bronchodilators in the yoga group. The authors of this study also reported that “the yoga group reported a better sense of well-being overall with more positive attitude and enthusiasm based on the Weekly Questionnaire” but this result was not quantified.

Barbara Benagh’s Approach

Before beginning exercises specifically designed to help people with asthma, Barbara typically does a kind of diagnostic test—a test you can do yourself to get some idea of what kind of condition your lungs are in. The idea is to inhale for two seconds, exhale for three seconds, and then hold your breath as long you comfortably can. The normal hold is more than thirty seconds, something Barbara says she can rarely do. She suggests that if you have asthma, you do this test every day. If your result is much below thirty seconds, you probably need to modify your breathing habits, or if your numbers start to go down from what they usually are, a flare-up may be in process and you might need medical attention.

Fundamental to Barbara’s approach to asthma is educating yourself. “The first thing is to learn what is a normal breath: mouth closed, twelve breaths or fewer a minute.” If you’re relaxed or doing Savasana, the exhalation should naturally be longer than the inhalation. “That’s the nature of a relaxed breath,” she says, but some people find it very hard to do.

The following program is Barbara’s updated version of the program that appeared in the Yoga Journal article that Ken read. Ken never worked with Barbara personally, but he based his own program on what she wrote and on his perception of what was working for him. He also consulted regularly with the yoga teacher whose classes he attended.

Breathing exercises should never leave you more anxious or more short of breath than when you started.

Breathing exercises should never leave you more anxious or more short of breath than when you started.

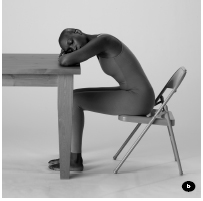

EXERCISE #1. DEEP RELAXATION POSE (Savasana), with relaxed breathing, mouth closed, five to ten minutes. This exercise allows you to watch your breathing, but does not involve doing anything to change it. Start by lying down in Deep Relaxation pose with your arms and legs splayed to the sides (figure 10.1a). Barbara says that this is the easiest position for diaphragmatic breathing. Sitting upright requires that you work against gravity when you exhale, and a big problem for someone with asthma is not being able to exhale. This is also why inversions, such as Shoulderstand, are helpful, a topic covered below. If lying down is uncomfortable, as it is for some people with asthma, Barbara recommends sitting in a chair and leaning forward over a table, resting your head on your folded arms, and turning your face to one side (figure 10.1b).

Once you are comfortable, begin breathing with your mouth closed. Next, tune into your exhalation; simply paying attention is the key. As you continue breathing, place your hands half on your ribs and half on your upper abdomen (figure 10.2), which will allow you to feel the movement of your rib cage and upper abdomen without interfering with that movement in any way. On your inhalation, you should feel the expansion in every direction except up (toward your head), and on your exhalation, you should feel relaxation everywhere except down. However, Barbara says that in an asthmatic the ribs may contract on the inhalation and expand on the exhalation. This is what she calls “reverse breathing.”

Some yoga students are taught to push the belly out on inhalation, but in Barbara’s experience, doing so does not guarantee that the diaphragm is working properly. She says that if you watch a sleeping baby or someone who is very relaxed, you’ll see the belly expand on the inhalation and retract on the exhalation, which has led to the conclusion that you’re supposed to push the belly out on the inhalation and draw it in on the exhalation. But this shouldn’t be a willed movement; rather it is caused by the diaphragm’s rise and fall during normal breathing. However, if you push your abdomen out, you don’t have to use your diaphragm at all.

Some yoga students are taught to push the belly out on inhalation, but in Barbara’s experience, doing so does not guarantee that the diaphragm is working properly. She says that if you watch a sleeping baby or someone who is very relaxed, you’ll see the belly expand on the inhalation and retract on the exhalation, which has led to the conclusion that you’re supposed to push the belly out on the inhalation and draw it in on the exhalation. But this shouldn’t be a willed movement; rather it is caused by the diaphragm’s rise and fall during normal breathing. However, if you push your abdomen out, you don’t have to use your diaphragm at all.

Once you have observed your breathing pattern, you can use the following exercises to teach yourself diaphragmatic breathing. They will heighten your awareness of when you are engaging your diaphragm and help you to strengthen it and use it more fully during breathing. Barbara suggests that you start with three to five breath cycles each of exercises two through six. Over time, as your symptoms allow, build up to ten to fifteen breath cycles of each exercise. Barbara says that with any of these exercises, it is fine to take several breaths between cycles of the exercise. Remember, do not force.

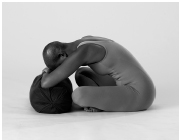

EXERCISE #2. THE WAVE. Start by lying on your back, with your knees bent, and your hands on your knees (figure 10.3a). As you exhale, gently bring your upper thighs toward your lower abdomen (figure 10.3b). As you inhale, let your feet drop toward the floor, arching your lower back. Keep your hips on the floor for the entire exercise, and allow your hands to remain on your knees as you move back and forth. The movement of your legs and abdominal muscles mimics the piston effect of natural breathing, which is different from the way most people with asthma breathe. Barbara stresses that the movements need not be large, though they may expand as you settle into the exercise.

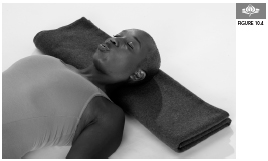

EXERCISE #3. PURSED-LIP EXHALING. Start by lying in Deep Relaxation pose (Savasana). When you are comfortable, purse your lips so that there is only a tiny opening for your exhalation (figure 10.4). Pursing your lips during the exhalation will engage the abdominals, causing a stronger exhalation than if you don’t use these muscles. Can you feel the abdominal muscles help to squeeze the air out? On your subsequent inhalation, you should be able to feel air being drawn down effortlessly into the bottom portion of your lungs. Barbara says that the ideal position for this exercise is sitting, but begin by lying down and practice that way until you are completely comfortable sitting up.

EXERCISE #4. 1:2 BREATHING. You can do this exercise either lying down in Deep Relaxation pose (Savasana) or sitting up. Start by softening the effort you use to inhale, and gradually decrease the length of your inhalation until it is half as long as your exhalation. For example, if you usually exhale for four seconds, you’ll end up inhaling for two seconds and exhaling for your usual four seconds. Don’t struggle to lengthen your exhalation, simply shorten your inhalation. If you feel anxious or short of breath at any time, take a few normal breaths before resuming the practice.

EXERCISE #5. 1:2 BREATHING, PAUSING AFTER THE EXHALATION. Repeat the last exercise but this time try to add a pause after your exhalation (but not after your inhalation). Gradually increase the length of the pause until it is as long as your exhalation.

EXERCISE #6. 1:1 BREATHING, WITH AN EXTENDED PAUSE AFTER THE EXHALATION. In this exercise, keep your inhalation equal in length to your exhalation, but add a pause after your exhalation (but not after your inhalation). Eventually, make your pause two to four times as long as your inhalation and exhalation. Barbara refers to this exercise as “Nature’s bronchodilator,” because she has found that it can effectively lessen an asthma flare.

While these exercises can be useful as “first aid,” if you are tempted to do them more than once an hour for symptom control, you probably should seek medical care instead. Barbara also advises against skipping asthma medications when doing these exercises, as some students try to do.

While these exercises can be useful as “first aid,” if you are tempted to do them more than once an hour for symptom control, you probably should seek medical care instead. Barbara also advises against skipping asthma medications when doing these exercises, as some students try to do.

In addition to the exercises above, Barbara recommends inverted poses for asthmatics. When your body is upside down, your diaphragm moves with gravity on the exhalation, not against it as it does when you are upright. Barbara says, “That’s why Headstand and Shoulderstand—Headstand in particular—are so good.” When she has problems with her breathing, she’ll do supported Shoulderstand over a chair, and Legs-Up-the-Wall pose (Viparita Karani). However, if like Ken, you have problems with dizziness when doing inverted poses, you may not be able to do these poses. See appendix 1, “Avoiding Common Yoga Injuries,” for more on doing inversions safely, and pp. 275–76 for instructions on how to do Chair Shoulderstand.

Besides breathing exercises and inversions, there are no yoga poses or practices that Barbara sees as specifically therapeutic for asthma. But she feels strongly a regular asana practice will be beneficial. She suspects the reason so many people with asthma feel so much better from their asana practice “is the fact that you have made the transformative decision to spend some time on your mat every day. That, even of itself, is so life changing, that you’re going to feel better for it.” She expands on her philosophy: “To me, what yoga is above all else is a behavioral modification. If you stop doing these things that you normally do, and instead you do yoga exercise, meditation, and breathing exercises every day, that’s going to make you feel better, and you’re going to be generally more healthy.”

Dysfunctional breathing habits can be entrenched; particularly for those with long-standing asthma, it can take a while to change. In the meantime, a fake-it-till-you-make-it approach can be useful. Barbara recommends mimicking healthy breathing until your body and your nervous system get reprogrammed. She sees changing your breathing as being the same kind of challenge as making any other change—losing weight, becoming a vegetarian, etc. “At first it’s difficult. But eventually it becomes second nature. It becomes a habit.” When people hear of Barbara’s prescription for asthma, some tell her that it can’t be that simple. Her reply is that the exercises are simple. What is not simple is doing them every single day. “You don’t even have to do them lying down,” she says. “I’ve done them sitting in my car. I’ve done them sitting in a plane. I do them any time my situation tells me I should. To me, it’s like brushing my teeth.”

Dysfunctional breathing habits can be entrenched; particularly for those with long-standing asthma, it can take a while to change. In the meantime, a fake-it-till-you-make-it approach can be useful. Barbara recommends mimicking healthy breathing until your body and your nervous system get reprogrammed. She sees changing your breathing as being the same kind of challenge as making any other change—losing weight, becoming a vegetarian, etc. “At first it’s difficult. But eventually it becomes second nature. It becomes a habit.” When people hear of Barbara’s prescription for asthma, some tell her that it can’t be that simple. Her reply is that the exercises are simple. What is not simple is doing them every single day. “You don’t even have to do them lying down,” she says. “I’ve done them sitting in my car. I’ve done them sitting in a plane. I do them any time my situation tells me I should. To me, it’s like brushing my teeth.”

Contraindications, Special Considerations, and Modifications

Shortness of breath, coughing, or wheezing may indicate poor control of asthma, in which case you may want to avoid an active asana practice. Cough is sometimes the only asthma symptom and may not be recognized for what it is. A decline in peak flow readings can signal an impending attack, and the need to refrain from an active practice. Colds, even if they are otherwise only mild, can exacerbate breathing problems and may necessitate caution.

Any exercise, including yoga, can bring on asthma attacks in susceptible individuals. If you use an inhaled bronchodilator, take two puffs fifteen minutes before starting your practice (a steroid inhaler won’t help if used this way). Since cold air also can trigger wheezing, a warm room is probably the best environment to practice in. It’s also useful to warm up and cool down slowly, as happens in most yoga classes. Be careful about working out in hot and humid rooms without replacing fluids, as dehydration can worsen asthma symptoms (see Chapter 5).

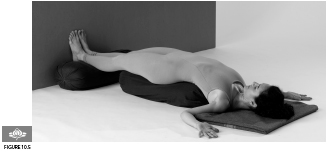

Barbara finds that a lot of the standard advice she’s heard about asthma in yoga circles didn’t work well for her. The rapid breathing technique known as Skull Shining Breath (Kapalabhati), which some teachers advocate for asthma, disagreed with her, particularly anytime she was having a flare-up of symptoms. Similarly, some teachers recommend backbends. “I would say, no, no, no, not backbends,” unless you’re totally asymptomatic. “When you’re symptomatic, backbends are virtually impossible to do. Your chest is so tight. It makes you start to cough and gasp.” She finds backbends take too much out of you if your energy is low, a common predicament among people with asthma. Backbends can also be overstimulating if you’re already anxious, also common in the condition. If, however, you are asymptomatic, Barbara believes that backbends, especially when supported and done as part of a regular practice, can be very useful to help open tight intercostals. Examples of restorative chest openers include Supported Bridge (Setu Bandha Sarvangasana) (figure 10.5) and Supported Cobbler’s pose (Supta Baddha Konasana) (figure 10.6).

OTHER YOGIC IDEAS

To help students suffering an asthma attack, Iyengar teachers often recommend supported forward bends. For example, the student might sit in a simple cross-legged position resting the chest and head on a bolster or stack of blankets placed on the floor (left). A student who is tight in the hips could lean forward resting the forehead on a chair (right). Students who are able to do so comfortably would be encouraged to stay ten minutes or longer in each pose.

Barbara advises that people with asthma refrain from any pranayama practices in which you extend the inhalation or retain the breath after inhaling. She worries that strong Ujjayi breathing may constrict the throat too much and contribute to breathing problems. If using a milder Ujjayi, she stresses not forcing it and making sure that the exhalation stays equal to the inhalation. Pranayama techniques like Sithali (see Chapter 25), where you inhale through the mouth, may also be inadvisable, since the cooled air could trigger bronchospasm, impeding the flow of air.

In many flowing classes including Ashtanga and power yoga, you are supposed to change from one posture to the next during a single inhalation or exhalation, a real strain for many people with asthma. Barbara believes that asthmatics should avoid such rapid-paced vinyasa flows. If you take such classes, Viniyoga teacher Leslie Kaminoff suggests that you never force the breathing. If your system isn’t accepting the prescribed breathing pattern, Leslie says, “it’s for a reason.” Whenever necessary, he suggests you take a catch-up breath, an extra breath in between, so your breathing is never strained.

A Holistic Approach to Asthma

People who engage in regular aerobic exercise have fewer asthma flare-ups, use less medication, and miss fewer days of school and work.

People who engage in regular aerobic exercise have fewer asthma flare-ups, use less medication, and miss fewer days of school and work.

Weight loss can be helpful because people who are overweight tend to breath more shallowly and that can make the airways more likely to go into bronchospasm.

Weight loss can be helpful because people who are overweight tend to breath more shallowly and that can make the airways more likely to go into bronchospasm.

Coughing, wheezing, or shortness of breath at night may signal a need for medication or a change in the time you take it.

Coughing, wheezing, or shortness of breath at night may signal a need for medication or a change in the time you take it.

Oral steroids like Prednisone can be necessary and even lifesaving for some patients—as Barbara and Ken can both attest. But they should be avoided when possible or used at the minimum effective dose and for the shortest possible time, because if used for a long period of time they can cause devastating side effects, including suppression of immunity, weight gain, high blood pressure, serious mood disturbances, as well as osteoporosis and other bone problems.

Oral steroids like Prednisone can be necessary and even lifesaving for some patients—as Barbara and Ken can both attest. But they should be avoided when possible or used at the minimum effective dose and for the shortest possible time, because if used for a long period of time they can cause devastating side effects, including suppression of immunity, weight gain, high blood pressure, serious mood disturbances, as well as osteoporosis and other bone problems.

Inhaled steroids are much safer than oral steroids but may thin bones, among other side effects. One simple way to reduce the amount that gets absorbed into your system is to rinse out your mouth after each dose.

Inhaled steroids are much safer than oral steroids but may thin bones, among other side effects. One simple way to reduce the amount that gets absorbed into your system is to rinse out your mouth after each dose.

The inhaled medication Cromolyn, while not as effective as inhaled steroids, appears to be extremely safe. If steroids still prove necessary, using Cromolyn might allow you to get away with a lower dose.

The inhaled medication Cromolyn, while not as effective as inhaled steroids, appears to be extremely safe. If steroids still prove necessary, using Cromolyn might allow you to get away with a lower dose.

Pneumonia vaccines and annual flu shots are advisable.

Pneumonia vaccines and annual flu shots are advisable.

Take steps to lower your exposure to polluted air, both indoors and outdoors (see Chapter 4).

Take steps to lower your exposure to polluted air, both indoors and outdoors (see Chapter 4).

The overwhelming majority of people with asthma have environmental allergies that can trigger inflammation and reduced lung function. Avoidance is key.

The overwhelming majority of people with asthma have environmental allergies that can trigger inflammation and reduced lung function. Avoidance is key.

If you have pets, keep them out of your bedroom since you probably spend more time there than in any other room. Also avoid wool, which acts as a magnet for dander. Try cotton instead.

If you have pets, keep them out of your bedroom since you probably spend more time there than in any other room. Also avoid wool, which acts as a magnet for dander. Try cotton instead.

Dehumidifiers eliminate excess moisture that can lead to the buildup of mold and dust mites.

Dehumidifiers eliminate excess moisture that can lead to the buildup of mold and dust mites.

On-the-job exposures to chemicals, molds, and other irritants and allergy-inducing substances can play an unrecognized role in exacerbating, even causing, asthma. Wearing protective equipment, limiting exposures, and if necessary, getting a different job or different job assignment may be advisable.

On-the-job exposures to chemicals, molds, and other irritants and allergy-inducing substances can play an unrecognized role in exacerbating, even causing, asthma. Wearing protective equipment, limiting exposures, and if necessary, getting a different job or different job assignment may be advisable.

Food allergies are an underrecognized trigger of asthma attacks, particularly life-threatening ones. Nuts, wheat, soy, and eggs can be problematic for some. An “elimination diet” (see Chapter 4) can help sort out what’s okay and what’s not.

Food allergies are an underrecognized trigger of asthma attacks, particularly life-threatening ones. Nuts, wheat, soy, and eggs can be problematic for some. An “elimination diet” (see Chapter 4) can help sort out what’s okay and what’s not.

Diet can play a role in either fueling or cooling down inflammation (see “A Holistic Approach to Arthritis,” Chapter 9).

Diet can play a role in either fueling or cooling down inflammation (see “A Holistic Approach to Arthritis,” Chapter 9).

The spices ginger and tumeric have anti-inflammatory properties and can be used in cooking or taken as supplements.

The spices ginger and tumeric have anti-inflammatory properties and can be used in cooking or taken as supplements.

Ken feels his yoga practice helped him to understand “that there’s a whole lot more to the way you breathe than simply something that’s mechanical and keeps you alive,” and he became much more conscious of the entire process. Besides keeping up his yoga practice and doing the exercises in Barbara’s article, he found a recording of breathing practices by Dr. Andrew Weil and started doing them. “I would try Barbara’s techniques, and then sometimes I would try Andy Weil’s techniques. I kind of came to my own method, I guess.” He also does supported backbends lying down over bolsters at the beginning and end of his yoga practice, because he finds they help open his chest.

This kind of pragmatic approach is completely in line with Barbara’s philosophy. “It doesn’t matter what the problem is, no one method works for everybody. If something doesn’t work, I throw it out. If it does work, I keep it in.” Her suggestion for customizing your own program: “Attention, trial and error, persevering until you come up with something that reliably works.”

Just over two years ago, with his doctor’s blessing, Ken was able to get off steroids and he’s been steroid-free ever since (although he does still occasionally need to use Albuterol, the bronchodilator). In addition, Ken is still working on becoming a full-time nose breather. Barbara’s article had made him aware he was a mouth breather, and he understands why that’s a problem, but finds it a challenge to change such an ingrained habit.

As a result of the practices, Ken’s awareness of his breathing and his ability to regulate it extend beyond his yoga mat. “I used to breathe very shallowly. I definitely breathe more deeply and more slowly now. I’m very conscious about the exhale, so I spend a lot of time measuring. Am I exhaling at least twice as long as I’m inhaling? Am I pausing after the exhale? Am I making sure I’m not pausing after the inhale? It’s a very conscious thing, when I’m walking, when I’m on the subway, whatever.” Ken has found the 1:2 breath practice so useful that he does it during the course of his day as often as he can, and is trying to make it his normal way of breathing.

Beyond improving his asthma, the exercises have made breathing more pleasurable, Ken says. “Breathing always used to be a struggle for me, even in the best of times.” Now, he says, “breathing feels good, emotionally as well as physically.”

From a yogic point of view, of course, breath is intimately connected to your emotions and to your spirit. Indeed, yogis like to point out that the roots of the words spirit and respiration are the same. In Sanskrit the word prana means both breath and life force. Bring awareness to your breath, yogic philosophy teaches, and you can calm the mind and get closer to the source of wisdom inside you, the calm inner witness that some people call spirit.

The changes Ken has experienced have been so profound that they’ve transformed his relationships to the people around him, too. “I’m much calmer,” he says. “I used to be very high stress. I was a nightmare to work for. I would just get people all excited and running around. That is gone from my life. Even the people at work say, ‘It’s really nice to be around you now.’ My kids have said it, my friends have said it, so it must be true.”