CHAPTER 11

BACK PAIN

JUDITH HANSON LASATER calls herself a yoga teacher who also happens to be a physical therapist. She was already teaching yoga when one day, some thirty-five years ago, it occurred to her she should become a PT, “because I wanted to be a better yoga teacher. My husband asked me, ‘Have you ever been to one?’ No. ‘Do you know what they do?’ No. ‘Do you know anything about it?’ No. But I literally woke up and knew that was what I wanted to do.” This intuition proved to be a good one. Her PT training gave her a much deeper understanding of human anatomy and kinesiology and has allowed her to take what she’s learned back to other yoga teachers to help them to become more professional and better at communicating with doctors. Judith herself regularly gets referrals from MDs, some of whom she’s never even met. Judith also holds a doctorate in East-West psychology, and is the author of six books on yoga, including Relax and Renew: Restful Yoga for Stressful Times, on the practice and therapeutic aspects of restorative yoga. She teaches in the San Francisco Bay Area and worldwide.

JUDITH HANSON LASATER calls herself a yoga teacher who also happens to be a physical therapist. She was already teaching yoga when one day, some thirty-five years ago, it occurred to her she should become a PT, “because I wanted to be a better yoga teacher. My husband asked me, ‘Have you ever been to one?’ No. ‘Do you know what they do?’ No. ‘Do you know anything about it?’ No. But I literally woke up and knew that was what I wanted to do.” This intuition proved to be a good one. Her PT training gave her a much deeper understanding of human anatomy and kinesiology and has allowed her to take what she’s learned back to other yoga teachers to help them to become more professional and better at communicating with doctors. Judith herself regularly gets referrals from MDs, some of whom she’s never even met. Judith also holds a doctorate in East-West psychology, and is the author of six books on yoga, including Relax and Renew: Restful Yoga for Stressful Times, on the practice and therapeutic aspects of restorative yoga. She teaches in the San Francisco Bay Area and worldwide.

The first time Bonnie Willdorf’s back “went out” was in 1980 when she was lifting an infant out of a car. “I had sciatica, with pain going down my right leg all the way to the foot. For two or three years in a row, I was flat on my back for a few months at a time.” Another long flare-up of back pain a few years later prompted a trip to a surgeon, who as surgeons are wont to do, recommended an operation. “He said, ‘Maybe we should schedule you,’ and then the next day I got better.”

Drawing the obvious conclusion that there was a psychological component to her pain, Bonnie recalls a month-long trip to the Southwest that started with so much pain she didn’t think she could continue. “By the second day it was gone, because I was on vacation.” When she continued over the years to have flare-ups, she consulted various orthopedists and tried physical therapy, but other than soaking in a hot tub nothing seemed to help much.

Besides stress, Bonnie felt her back problems were probably related to “bad body mechanics. I’ve always had bad posture. I tend to hunch my shoulders over and stick my head forward. I was not an athletic person growing up. I grew up in a family where the only muscle you were supposed to exercise was the one in your head. We did poetry readings on Sundays, we didn’t take hikes.” She thought perhaps yoga could help. At a friend’s suggestion, she began to study with Judith.

When she started with Judith in 1993, Bonnie couldn’t do a lot of the asana in class because the poses hurt her lower back. But Judith always has a “hospital row” in the back of her classes, and a “hospital row assistant” who puts people in restorative positions, under Judith’s direction. Gradually Bonnie was able to move out of hospital row, and then decided to study privately with Judith to work more intensively on a solution to her back pain.

Overview of Back Pain

Nearly everyone experiences low back pain at one time or another. Current estimates rate back problems as the second most common reason for visiting MDs, the top reason for visiting a chiropractor, and the leading cause of disability of people under forty-five. The most common malady is referred to as low back strain, a catch-all phrase that includes minor muscle, ligament, and joint problems in the lumbar spine and surrounding tissues. While a seemingly trivial event such as sneezing or getting out of a chair can trigger a bout of back pain, doctors recognize that the pain is usually the culmination of years of subtle injuries and trauma to the back. Generally more severe is sciatica, a condition most commonly caused when the shock-absorbing disk that separates two spinal vertebrae bulges out and compresses a nerve root exiting the spinal cord, causing pain which radiates down the leg, sometimes all the way to the foot. A few people have sciatic leg pain but no pain in the back.

The medical profession’s approach to back pain has shifted a lot in recent years. When I was in medical training, bed rest was the standard approach, and that’s what was recommended to Bonnie early on. Doctors now realize that lying around is actually counterproductive, leading to a decrease in conditioning and an increase in pain. The longer you stay in bed the more muscle mass you lose (up to 3 percent per day, according to some authorities), and the resulting loss of strength can interfere with your rehabilitation, and force you to overwork other muscles to compensate. Rather than babying a back injury, doctors now recommend people start gentle activities the first day.

How Yoga Fits In

Though physicians tend to take a one-size-fits-all approach to low back strain, from a yogic perspective this doesn’t make a lot of sense. There are dozens of possible causes of back pain other than sciatica. Ligaments can be strained. Arthritis can develop in the small facet joints that link one vertebra to the next. Due to postural problems, scoliosis, or injuries, the vertebrae and the ribs may be poorly aligned with one another. Whatever the underlying cause, the result may be muscle spasms in a variety of locations that can be more painful than the original problem. Given all the possibilities, it’s extremely unlikely that the same set of exercises, the same medications, or the same operations will help everyone.

Despite the ubiquity of low back pain, it is one of the conditions that modern medicine does the worst job of treating. Partly due to the imprecision of diagnosis and relative ineffectiveness of most conventional treatments, many people with back pain end up on the conveyor belt that sooner or later leads to surgery. These operations are often not terribly effective, usually fail to address major underlying factors, cause their own problems, and in the vast majority of cases can be avoided. While there are instances when surgery is required—sometimes on an emergency basis—back operations continue to be one of the most commonly performed unnecessary surgeries. Keep in mind when evaluating your therapeutic options that most cases resolve in six to eight weeks, pretty much no matter what you do. Even with herniated disks, the overwhelming majority of people recover without an operation. Above all, you do not want to rush into surgery, when other, safer, less invasive methods are available—methods that are in the long run more effective and less likely to cause problems. If you are scheduled for elective surgery, you might consider canceling the operation and seeking the opinion of the best yoga therapist or bodyworker you can find to make sure you’re not about to make a huge mistake. They may be able to figure out what set you up for back trouble in the first place, by examining factors like posture, your emotions, and your work and living environment. Failure to address these issues is another reason back surgery is less successful than it might be, and why many surgical patients wind up needing a second or third operation to address problems that develop at another level of the spine.

Scary as herniated disks may sound, studies reveal that many people with no back pain have them, while others who have significant pain show no evidence of herniation. An MRI can tell you if you’ve got a herniated disk, but it takes sophisticated physical examination skills to know if that is the likely cause of your problems. Unfortunately, because of the ubiquity of high-tech tests, medical students no longer learn to examine patients as well as previous generations of doctors did, and when herniation shows up on an MRI, the risk is that some surgeon may want to operate on it without knowing whether it’s related to your pain or not. A good PT is often much better at doing a hands-on assessment than many doctors, including some orthopedists.

Scary as herniated disks may sound, studies reveal that many people with no back pain have them, while others who have significant pain show no evidence of herniation. An MRI can tell you if you’ve got a herniated disk, but it takes sophisticated physical examination skills to know if that is the likely cause of your problems. Unfortunately, because of the ubiquity of high-tech tests, medical students no longer learn to examine patients as well as previous generations of doctors did, and when herniation shows up on an MRI, the risk is that some surgeon may want to operate on it without knowing whether it’s related to your pain or not. A good PT is often much better at doing a hands-on assessment than many doctors, including some orthopedists.

Although conventional physicians tend not to examine the role of stress in back pain, many people, like Bonnie, see a connection between their back problems and psychological tension. When the body’s stress-response system is activated, tension in muscles increases, which by itself can cause pain. Some experts outside of the mainstream, most notably physician John Sarno, the author of Healing Back Pain: The Mind-Body Connection, argue the cause is usually entirely psychological. Dr. Sarno believes that back muscles go into spasm and cause pain because of mental tension, and that if you can get to the root cause of the tension the pain will disappear.

Yoga teacher Aadil Palkhivala also sees the connection between emotional difficulties and back pain, which is reflected in the expression “unable to bear the burden.” He suggests writing in a journal to find relief. “Burden the page with your burden,” he says. As someone who has dealt with his own significant back injuries, Aadil reports that he “can feel the nerves starting to relax as I write.” When the nerves relax, when the balance in the autonomic nervous system is shifted to the restorative parasympathetic side, the deep muscles that may be the source of the pain start to let go.

From a yogic perspective, other factors are important, too. Beyond stress, and emotions like anger and dissatisfaction, yoga links back pain to posture, muscle tightness, and muscle weakness, as well as to a lack of body awareness—all issues that yoga is very effective in addressing.

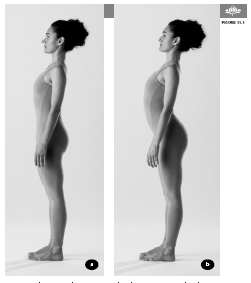

Posture is a critical factor. A person with good posture has a spine that curves gently forward in the lower back and backward in the upper back. This S-shaped curve acts like a shock absorber for the pressures placed on the spine. When these healthy curves either flatten or arch too much, it can compress the vertebrae and the spinal disks between them, causing pain or irritation of the nerves coming out of the spine.

The sloped shoulders, forward head position, and C-shaped slump of the upper back so typical of modern life can lead to chronic neck and back pain. In some people, partly due to tightness in the hamstrings, the pelvis tips backward and the lower back rounds, reversing its normal inward curve. This position puts enormous strain on the spinal disks in the lumbar region and can lead to herniation and sciatica. For more on the yogic approach to improving slouching posture, see chapters 2 and 13.

Doctors often prescribe abdominal exercises like stomach crunches to people who have had back pain, to prevent recurrences once they are out of the acute phase. Such advice reflects the notion that most back pain is related to weak abdominal muscles. From a yogic perspective, abdominal weakness is often part of the problem, but that approach is imprecise. Indeed, too many crunches or other abdominal exercises can increase the tightness in hip flexors like the psoas (a large muscle deep in the abdomen that connects the lower spine to the top of the leg bone), potentially exacerbating some back problems. Besides tight hamstrings, many people with back pain have tight hip rotators in the pelvis. Yogis also realize that often the back extensors, the muscles that run on either side of the spine and keep you from slumping, are weak. The yogic approach is to determine which specific muscles need strengthening and which ones need stretching, and design a program to address those needs. This individually tailored yoga approach is much more likely to be effective than the kind of blanket recommendation to strengthen your abdominal muscles typically issued by MDs.

a) Normal posture b) Excessive lumbar curve, swayback

Some people get back pain because of excessive flexibility in their joints. Pain can be the result, for example, of arching the lumbar spine too much, exaggerating the normal lower back curve. This situation, known as swayback (figures 11.1a & b) is more seen in women, and can be exacerbated due to the hormonal changes during pregnancy (and the weight of the baby). Weakness of the lower abdominal muscles can contribute to swayback. By learning to engage these muscles (move your navel toward your spine is the instruction yoga teachers often give), students can learn to flatten out some of the excess in the lower back curve. While sit-ups may be useful in this situation, a number of asana systematically address weakness, as well as lack of flexibility, in the four different layers of muscles in the abdomen, in ways that exercises like stomach crunches don’t.

Independent of the effect on individual muscles, asana movements help back pain by improving the circulation that brings nutrients to the intervertebral disks while removing toxins. Gelatinous shock absorbers that cushion vertebrae that are adjacent to each other, the disks don’t have their own independent blood supply, and thus depend on movement of surrounding structures to aid in the delivery of nutrients. Movement causes the disks to be compressed, which squeezes out stale disk fluid, and then to expand, bringing a fresh supply. Yogis believe that asanas, with their systematic stretching, bending, wringing, and soaking of the disks are particularly effective at delivering the oxygen and other nutrients the disks need to remain healthy and pain free.

Attention to breath, as always, is part of the yogic prescription for back pain. Slow, deep breaths help ratchet down an overactive stress-response system, which can lead to muscle relaxation. With the fuller exhalations that occur when the abdominal muscles assist in pushing the air out, more oxygen is brought into the body on the subsequent breath. In addition, the undulations of deep inhalations and exhalations gently massage the spinal column, which also helps bring nutrients to spinal disks.

Awareness is crucial to the yogic approach to back pain. Many people with bad postural habits may simply not notice what they are doing. It becomes natural to bring the awareness of alignment learned during asana practice to your everyday life. You may notice, for example, your habit of slumping in an office chair, on a couch, or even standing in line. Again and again, says Judith, you may need to remind yourself to be attentive to how you are using your body when you wash dishes, pick up the laundry, watch TV, or engage in any of the routine activities that are part of everyday life.

Awareness and the focus on breathing differentiate some yoga stretches from similar-looking exercises you might get in conventional physical therapy. In yoga asana, your attention is focused on what you are doing and on how it affects sensations in your body and mind. Most PT exercises, in contrast, are usually done fairly mindlessly and mechanically, perhaps even while watching television. When you do PT exercises without awareness, without tuning in, they are exactly the same thing every day—rote and uninteresting. No wonder so many people stop doing them.

Yoga done right gets more interesting over time. Good yoga asanas don’t just improve the functioning of the physical body, they engage your mind. Bringing your attention to what you are doing, and precisely how you are doing it, builds the ability to feel your body’s signals. Bring yogic awareness and conscious breathing to standard PT exercises and my guess is that they, too, will be more effective. This greater proprioceptive awareness (your felt sense of your body position) also allows you to notice subtle changes that would once have eluded you—serving as an early warning system when stress, poor posture, or other factors may be leading to back pain.

The Scientific Evidence

A program of mindfulness-based stress reduction, which includes mindfulness meditation and hatha yoga, proved effective for patients with chronic pain, including back pain sufferers. There is also evidence that McKenzie physical therapy exercises, which use gentle backbends resembling yoga poses, can help with back pain. The large survey of yoga practitioners mentioned in chapter 1 found that 98 percent of more than one thousand people with back pain found yoga helpful.

Another survey supporting yoga’s effectiveness in back pain comes from an out-of-print book called Backache Relief, coauthored by Dava Sobel, author of Longitude and Galileo’s Daughter. The authors polled almost five hundred back pain sufferers to try to find out what had worked for them, asking about care from orthopedic surgeons, osteopaths, chiropractors, acupuncturists, Rolfers, and Feldenkrais practitioners, as well as the use of muscle relaxants, anti-inflammatory drugs, hot packs, ice packs, shoe orthotics, TENS nerve-stimulation units, and even marijuana. Overall, yoga was judged the “most successful of all approaches to backache relief for nonincapacitated backache sufferers—with twenty-three out of twenty-four survey participants [who did yoga] reporting significant long-term improvement.” Of note, the survey respondents who tried yoga through books, articles, and tapes got some relief but much less than those who worked with a yoga teacher (whether in a class or private session was not specified). Several participants recommended simple abdominal breathing (for instructions, see pp. 55–56), up to five minutes a day, to reduce stress and build abdominal muscle tone.

A recent randomized controlled study of twenty-two people, published in Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine, studied hatha yoga for people with chronic low back pain that had not responded to at least two modalities such as physical therapy and chiropractic. The six-week intervention included twice-weekly one-hour classes for six weeks consisting of gentle asanas, meditation, and relaxation. As compared to controls, the yoga group showed improvements in balance and flexibility, disability, and mood, though none of these reached the level of statistical significance. Three months later, eight of the eleven people in the yoga group completed a survey. Six of eight reported improvement in back pain since the completion of the study. Seven of eight reported ongoing benefit from the yoga intervention. All eight believed that yoga facilitated relaxation and greater awareness, and recommended yoga to other people with chronic low back pain.

A randomized controlled trial led by Kimberly Williams of West Virginia University School of Medicine compared the effects of an adapted regimen of Iyengar yoga on patients with chronic low back pain to a group that received a weekly informational newsletter. Of sixty subjects enrolled at the beginning of the study, forty-two completed the study. The yoga group attended sixteen weekly classes. Compared to controls, the yoga group experienced a 64 percent reduction in pain, a 77 percent reduction in “functional disability” (problems with accomplishing everyday tasks), and a 25 percent improvement in perceived control over pain. They also gained significantly in hip flexibility. Of those patients taking pain medication at the beginning of the study, 88 percent of the yoga group either reduced their dose or eliminated medication entirely as compared to 35 percent of controls.

A randomized controlled trial, published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, compared Viniyoga to conventional therapeutic exercise to a self-care book in 101 people with chronic low back pain. Patients in both the yoga and exercise groups had a seventy-five-minute class weekly for twelve weeks, while the third group received a booklet about strategies for coping with back pain. The yoga and exercise groups were encouraged to practice at home between sessions. At the twelve-week mark, the yoga group had a small but statistically significant improvement compared to the exercise group, and a large improvement compared to the booklet group. Between twelve and twenty-six weeks, only the yoga group continued to improve; the other groups worsened. When the participants were questioned twenty-six weeks after starting the protocol, 12 percent in the yoga group had sought back-related treatment from a health care professional, compared with 19 percent in the exercise group and 31 percent in the group given the booklet. In the yoga group, 21 percent had taken medication for back pain in the twenty-sixth week, compared to 50 percent of the exercise group and 59 percent in the booklet group.

Judith Hanson Lasater’s Approach

“There are many causes of back pain and many different ways it manifests and many different ways to approach it,” says Judith. “Some people just need a lot of stress reduction and posture education. Other people need stretching and strengthening.” While it sometimes seems like an inevitable part of aging, Judith feels that “in the overwhelming majority of cases, back pain can be prevented. Some problems are congenital, some are the result of accidents, but the majority have to do with how we use our bodies.” Her approach is to look for the simplest cause first. “I would look first at standing posture, sitting and driving posture, and sleeping posture.” She finds that “almost no one stands well,” a problem she suspects is related to “spending all of our time in chairs, which puts the maximum pressure on the disks and weakens the abdominal muscles.”

Like many of the back-pain students Judith sees, Bonnie had a sedentary job and the postural problems that typically accompany long periods spent in a chair. She tended to flatten her lower back, her head was held forward of her spine with her chin tipped up, and her shoulders were rounded forward, suggesting the interscapular muscles, the ones that hold your shoulder blades upright, weren’t doing their job.

Dr. Galen Cranz, a professor of architecture at the University of California at Berkeley and the author of The Chair: Rethinking Culture, Body, and Design, as well as a yoga practitioner and a teacher of the Alexander Technique, thinks that most chairs are poorly designed for spinal health, particularly for anyone under five foot six inches. She suggests sitting whenever possible with the feet flat on the floor and the sit bones (the bony prominence in each buttock) higher than the knees. This position allows the lumbar spine to maintain its normal, healthy inward curve. Ideally, the angle between the legs and the trunk, she says, should be around 120 degrees, but anything greater than 90 degrees is helpful. If your chair can’t be adjusted to this angle, you can place a book or cushion on the seat of the chair to raise the level of the hips, and another book on the floor if your feet don’t reach the ground. Otherwise she suggests scooting forward to perch on the edge of the chair, keeping your spine straight and maintaining a healthy angle between the legs and torso (this may not sound inviting but is a surprisingly comfortable position) (see Chapter 13).

Dr. Galen Cranz, a professor of architecture at the University of California at Berkeley and the author of The Chair: Rethinking Culture, Body, and Design, as well as a yoga practitioner and a teacher of the Alexander Technique, thinks that most chairs are poorly designed for spinal health, particularly for anyone under five foot six inches. She suggests sitting whenever possible with the feet flat on the floor and the sit bones (the bony prominence in each buttock) higher than the knees. This position allows the lumbar spine to maintain its normal, healthy inward curve. Ideally, the angle between the legs and the trunk, she says, should be around 120 degrees, but anything greater than 90 degrees is helpful. If your chair can’t be adjusted to this angle, you can place a book or cushion on the seat of the chair to raise the level of the hips, and another book on the floor if your feet don’t reach the ground. Otherwise she suggests scooting forward to perch on the edge of the chair, keeping your spine straight and maintaining a healthy angle between the legs and torso (this may not sound inviting but is a surprisingly comfortable position) (see Chapter 13).

Judith pays particular attention when people have radiating pain, because that indicates there is an impingement of the nerve, whether it’s coming from a herniated disk or from a tight piriformis muscle pressing on the sciatic nerve in the buttocks (which is often missed by doctors). In Bonnie’s case, the pain radiated down her leg all the way to the foot and suggested disk herniation in the lumbar region.

After taking a history, the first thing Judith often does in a private session with a student with back pain is ask to see a position in which the student is pain free. Often it’s lying on the back with the knees bent, which eliminates all the stress of gravity. Judith tells the rare students who can find no position of comfort that they need to seek a medical evaluation before she can work with them. She wants to be sure there isn’t something that is beyond her area of expertise at the root of the problem.

While serious or even potentially life-threatening causes of back pain are a lot less common than poor posture and stress, sometimes a trip to the doctor is definitely in order. The older you are, the more you should consider seeing a doctor before you consult a yoga therapist. Four major medical conditions that can cause pain similar to what accompanies run-of-the-mill low back strain include:

1. Infection. Rarely, the spinal bones themselves become infected, but more commonly back pain can be caused by a kidney infection. Suggestive symptoms include fever, and for kidney infections, frequent and uncomfortable urination.

2. Cancer. Multiple myeloma is a bone marrow cancer that can take up residence in the spine. Other cancers, notably breast and prostate, can spread to bones of the spine.

3. Spinal Fracture. Both cancer and osteoporosis can predispose to spinal fractures. Unrelenting pain not relieved by changing positions may be an indicator.

4. Neurological Problems. Several back conditions can cause loss of sensation in the legs or difficulty with urination or bowel control. These symptoms should prompt an immediate medical evaluation.

Because Bonnie had already had a number of medical evaluations and Judith could see a clear relationship between her symptoms and her posture as well as her stress levels, she felt comfortable proceeding, and confident that yoga could help. Judith lists a number of goals the following yoga routine was designed to address for Bonnie: “I was looking for abdominal strength, more lumbar curve, greater strength in the interscapular [between the shoulder blades] muscles, and a better head position.”

Here is the sequence of the poses and instructions that Judith provided for Bonnie:

EXERCISE #1. CAT/COW, ten to twenty times. Start by kneeling on all fours, with your spine in neutral position, your knees directly beneath your hips, and your hands beneath your shoulders. Exhale and gently arch your spine (figure 11.2a), then inhale and round your back (figure 11.2b). Move slowly between the two positions, coordinating the movements with your breath.

EXERCISE #2. CAT/COW, turning the head and looking back, five times to each side. Start on all fours as before, in neutral position. As you exhale, turn your head and look back at your right foot. Let your trunk bend on the right side and stretch on the left side as you look back. As you inhale, return to the starting position. Then, exhale and look toward your left foot, feeling the response in your spine.

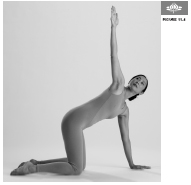

EXERCISE #3. CAT/COW, lifting arm toward ceiling and following it with your eyes, three to five times on each side. From the same all-fours position, inhale, rotate your trunk, and lift your right hand up toward the ceiling and follow it with your eyes. On the exhalation lower your hand. Repeat on the other side. Do the entire exercise three to five times, alternating sides. “This is a rotational movement,” Judith says, “but it’s in a different relationship to gravity than a seated twist and so often feels better than sitting and twisting.” All these Cat/Cow exercises create mobility in your spine.

EXERCISE #4. COBRA VARIATION, with arms at your sides, three times. Lie facedown on your mat. Keeping your legs on the floor at least hips’ width apart and your knees turned inward toward each other, raise your hands slightly and lift your upper body into a slight backward arch as you exhale. Hold for several breaths and then lower yourself down as you exhale. Turn your head to one side and rest. This is strengthening for the lower-back muscles and mobilizes the middle back area, which often becomes stiff from sitting and bending forward at a desk for hours. Try this three times if it feels good, alternating the direction in which you turn your head when you come down.

EXERCISE #5. COBRA VARIATION, with arms bent, three times. Lie facedown on your mat. Move your arms out to the sides, so your body is in the shape of the letter T, and then bend the elbows to 90 degrees. From this position, exhale as you come into a gentle backbend. Be sure to keep your legs on the floor and your chin slightly dropped so as not to compress your neck. Stay for several breaths and come down as you exhale. Rest, turning your head to one side. When you repeat, turn your head the other way.

EXERCISE #6. COBRA VARIATION, with arms extended in front of body, two times. Repeat Cobra pose as in the previous exercise, using the same breathing, this time with your arms forward, like Superman, over your head. You’ll be tempted to lift your legs, but be sure to keep your legs on the floor. Judith says that this exercise uses the intrinsic back muscles to lift you instead of the arms and is quite strengthening. Try this two times, exhaling as you lift.

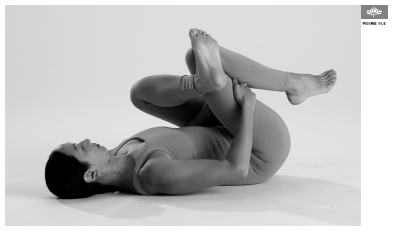

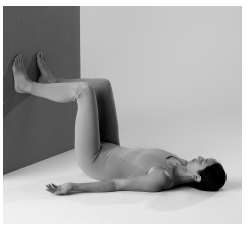

EXERCISE #7. SUPINE HIP ROTATOR STRETCH, three times on each side. Start by lying on your back with your knees bent. As you exhale, tilt your pelvis slightly backward and bring your lower back to the floor and your right knee halfway in toward your chest. Take your left foot and cross it over your right knee, and with your right hand, reach around the outside of your right leg and hold the back of your right thigh just above the bend of the knee. Place your left hand on the inside of your left knee. On an exhalation, simultaneously bring your right knee toward you as you gently push your left knee away. Feel the stretch in your outer left hip (figure 11.8). Hold for several breaths. To come out of the pose, exhale and place your right foot and then your left on the floor with your knees bent. Repeat on the other side. Be sure to keep breathing as you practice.

Judith says that this exercise is a good stretch of the external rotators of the hip. If people are really tight in their rotator muscles, it interferes with the ability of the pelvis to move in normal daily activities like walking. When the rotators hold the pelvis too much, the biomechanical forces of movement are transferred up to the next movable segment in the kinetic chain, which is the lumbar spine.

For people with back pain, the standing poses, such as those below, are very important because of the loosening effect they have on the hip joints. They stretch all the major muscle groups around the hip joints: the adductors, the quads, the rotators, and the hamstrings. Judith says that if you stop doing them for a week, you will feel the difference.

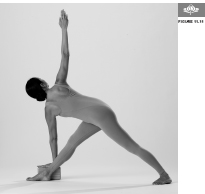

EXERCISE #8. TRIANGLE POSE (Trikonasana), three to five breaths on each side, twice. Stand with your feet three and a half feet to four feet apart. Turn your right foot out 90 degrees and your left foot in 15 to 30 degrees. Raise your arms to your sides with the palms down. On an exhalation, bend at the hips and bring your right arm down onto a block placed outside and just behind your right foot (figure 11.9). Judith suggests allowing the top of your pelvis in the back to slightly rotate forward to stretch the rotators on your back hip. Slightly rotate the chest up toward the ceiling. Be sure to allow a normal inward curve in your lower back. In other words, don’t tuck your pelvis. Hold for three to five breaths and come up on an exhalation. Repeat on the other side, and then do both sides again.

EXERCISE #9. WARRIOR I (Virabhadrasana I), three breaths on each side. Stand with your feet three to four feet apart. Turn your right foot out 90 degrees and your left foot in 30 to 40 degrees. Bring your hips around so they are square with your front foot. Raise your arms over your head and bend your front leg to 90 degrees to come into the pose, being careful not to allow the knee to extend beyond the ankle or drift inward. Judith says this pose stretches the hip flexors and the quadriceps (the big muscles in the front of the thighs). It is not only strengthening but also empowering. Hold for three breaths, and repeat on the other side. Keep breathing as you move.

EXERCISE #10. REVOLVED TRIANGLE POSE (Parivrtta Trikonasana), three breaths on each side, twice. Stand with your feet as in Warrior I. Raise your left arm and on an exhalation twist your spine, place your left hand on a block placed on the outside of your right foot, and lift your right arm toward the ceiling (figure 11.11). Move slowly so you can pay attention to how the pose feels for your lower back. Inhale as you come out of the pose. Repeat on the other side, again moving into the pose on your exhalation and coming out on your inhalation. Judith says this pose is a strong weight bearing stretch of the rotators, and is only for those who feel okay in the lower back area and are not in an acute phase. Stay for three breaths. Do the pose twice on each side.

Using a block under the lower hand in poses like Triangle and Revolved Triangle maximizes the therapeutic benefit by creating more stability and allowing you to ground yourself more completely in your legs, which in turn creates more freedom in the lower spine and allows you to rotate your rib cage more easily. The added height also allows greater movement of your spine and ribs.

Using a block under the lower hand in poses like Triangle and Revolved Triangle maximizes the therapeutic benefit by creating more stability and allowing you to ground yourself more completely in your legs, which in turn creates more freedom in the lower spine and allows you to rotate your rib cage more easily. The added height also allows greater movement of your spine and ribs.

EXERCISE #11. CHILD’S POSE (Balasana). Sit with your toes together and your knees separated to a comfortable degree. Then fold forward between your knees and stretch your arms out behind you, palms up, along your sides. Place your forehead on the floor, and keep your lower back rounded. Stay in the pose for thirty seconds to two minutes if it feels good. Keep your breathing soft.

Yogic Tool: HANDS-ON ADJUSTMENTS. When Bonnie did Child’s pose in class, Judith or one of her assistants would typically give Bonnie an assist. Judith would stand behind Bonnie, and put her hands with her fingers pointing toward her own body over Bonnie’s sacroiliac joint area, where the spine and the pelvis meet, pressing diagonally back and down. She doesn’t just press down toward the floor or back toward the student’s feet. Pressing diagonally down and back, she says, relieves all the erectors by stretching them and the connective tissue in the area. The lower back erectors often get tight, in part because of our sitting and standing posture.

OTHER YOGIC IDEAS

David Coulter, former anatomy professor, yoga teacher in the tradition of the Himalayan Institute, and author of Anatomy of Hatha Yoga, has found that a supine position with the knees bent and the soles of the feet against a wall allows you to do a gentle motion of the lower back (the lumbar spine) that most people find soothing. Feel the small curve in your lower back. Then, as you exhale, press your feet into the wall to coax your lumbar spine to flatten toward the floor. Release your foot pressure as you inhale to allow the curve to return to your lower spine. Repeating this several times allows you to begin moving your spine in a safe and controlled way.

EXERCISE #12. RELAXATION POSE (Savasana). Lie on the floor with your head supported, your eyes covered with a soft cloth, and your arms and legs at a comfortable distance from your body (figure 11.13). You may find the pose easier on your back if you place a bolster or a rolled blanket under your knees. Many students also appreciate a smaller roll under their Achilles tendons at the back of their ankles. When you are comfortable, breathe slowly and allow yourself to sink into the floor, letting goof all tension and allowing your mind to focus on the sensation of your breath. To come out of the pose, bend your knees and roll slowly to your right side. Rest a moment, then use your arms to push yourself to a sitting position (see Chapter 3). Remain quiet for a few more moments before getting up. Judith always recommends this pose for people with lower back pain. She says, “This is the most important pose we can practice.”

Head-to-Knee pose (Janu Sirsasana) can be trouble with back pain.

Contraindications, Special Considerations, and Modifications

Forward bends, particularly if there is also an element of twisting involved as in Head-to-Knee pose (Janu Sirsasana), can compress nerve roots and aggravate sciatica (figure 11.14). People with lumbar disk problems generally shouldn’t be doing seated twists or forward bends. Seated forward bends are harder on the lumbar spine than standing forward bends because it is more difficult to tip the pelvis forward when it’s on the ground. Although standing forward bends cause less pressure in the spinal disks than seated versions, the pressure can still be too high to make these poses safe for people with acute back injuries. The safest forward bends for the low back are those done lying on your back, as when you bring your knees to your chest. In the acute stage avoid Boat pose (Navasana), straight leg raises, Staff pose (Dandasana), and Lotus pose (Padmasana).

Backbends are sometimes part of the therapy for back problems, but in other cases are not appropriate. They can be dangerous for anyone with spondylolisthesis, a condition in which one vertebra slips forward relative to its neighbors. A backbend could worsen the slippage, potentially compressing nerve roots in the spinal canal.

There are so many causes of back trouble that what’s appropriate for back pain will vary widely. In general, the best approach is to have an experienced teacher look at you and come up with a personalized evaluation of what’s safe. The better you develop your body awareness, the more you will be able to make these determinations yourself.

Working through mild discomfort appears to be appropriate for people with back pain. Studies suggest that the speediest recoveries are made by back pain sufferers who began physical therapy the day of the injury or the day after, and the same is likely to be true of yoga. Avoid any sudden changes of position, and step rather than jump into poses. Even when symptom free, take special care coming in and out of asana, as it is often during transitions—when attention tends to flag—that back injuries occur.

A Holistic Approach to Back Pain

Frequent changes of position are natural and healthy. At work, try to take regular breaks and set up your office so that you have to get up to file or answer the phone.

Frequent changes of position are natural and healthy. At work, try to take regular breaks and set up your office so that you have to get up to file or answer the phone.

When lifting heavy objects, use your legs as much as possible. If you need to bend forward, don’t bend at the waist. Fold forward from the hips without allowing your lower back to round. Try to maintain a normal curvature in the lower and upper spine and avoid twisting and bending simultaneously, as this is a common mechanism of back injury.

When lifting heavy objects, use your legs as much as possible. If you need to bend forward, don’t bend at the waist. Fold forward from the hips without allowing your lower back to round. Try to maintain a normal curvature in the lower and upper spine and avoid twisting and bending simultaneously, as this is a common mechanism of back injury.

Wear the right shoes. Narrow-toed shoes lead to tension in the legs and back. High heels shorten the calf muscles and hamstrings and can contribute to back strain.

Wear the right shoes. Narrow-toed shoes lead to tension in the legs and back. High heels shorten the calf muscles and hamstrings and can contribute to back strain.

Topical creams containing capsaicin or arnica and liniments based on methyl-salicylate, menthol, and camphor are soothing and very safe.

Topical creams containing capsaicin or arnica and liniments based on methyl-salicylate, menthol, and camphor are soothing and very safe.

Many people find applications of ice helpful and, once the injury is starting to heal, switch to moist heat, either alone or alternating with ice. Heat can also be useful to reduce stiffness before attempting to exercise.

Many people find applications of ice helpful and, once the injury is starting to heal, switch to moist heat, either alone or alternating with ice. Heat can also be useful to reduce stiffness before attempting to exercise.

Willow bark tea (which contains the active ingredient of aspirin) may be useful.

Willow bark tea (which contains the active ingredient of aspirin) may be useful.

If your pain is severe and does not respond to over-the-counter or prescription anti-inflammatory pain relievers, ask your doctor about prescribing opioids. They are generally more effective and safer than many other pain medications, but due to exaggerated fear of addiction, they aren’t used as often as they ought to be.

If your pain is severe and does not respond to over-the-counter or prescription anti-inflammatory pain relievers, ask your doctor about prescribing opioids. They are generally more effective and safer than many other pain medications, but due to exaggerated fear of addiction, they aren’t used as often as they ought to be.

The evidence on acupuncture for back pain is mixed, but it is very safe and worth considering.

The evidence on acupuncture for back pain is mixed, but it is very safe and worth considering.

Hands-on bodywork approaches, such as chiropractic, physical therapy, therapeutic massage, and osteopathy can help you through a flare-up of back pain (though not all osteopaths do spinal manipulation, so ask before making an appointment).

Hands-on bodywork approaches, such as chiropractic, physical therapy, therapeutic massage, and osteopathy can help you through a flare-up of back pain (though not all osteopaths do spinal manipulation, so ask before making an appointment).

Judith finds many people with back pain get better results if they combine their yoga with bodywork such as myofascial release designed to iron out the kinks in muscles and connective tissue, and free up scar tissue and other residuals of past injuries.

Judith finds many people with back pain get better results if they combine their yoga with bodywork such as myofascial release designed to iron out the kinks in muscles and connective tissue, and free up scar tissue and other residuals of past injuries.

I have found the Alexander Technique, which stresses postural education, particularly effective for back problems, both as prevention and treatment. The Feldenkrais Method may be similarly valuable.

I have found the Alexander Technique, which stresses postural education, particularly effective for back problems, both as prevention and treatment. The Feldenkrais Method may be similarly valuable.

Working with Judith helped Bonnie’s back a lot. “I started having fewer flare-ups, and felt like my back was getting strengthened.” She also acquired tools that could help her ward off trouble. “I had poses and relaxation practices that I could do when I felt like things were going to start up.” Originally, if she didn’t feel good, she wouldn’t go to class. “Then I came to a point where I realized if I didn’t feel good and I went, I’d feel better. That was a revelation for me.”

She adds, “I just got more confident about being physical. For years, I wouldn’t do any yoga at home, because I was so afraid that I would do it wrong, and then I would get hurt. But five years ago, I got to the point where I felt I can do some poses, and if I’m not doing them perfectly, it doesn’t matter. It just matters that I’m doing them. I can lie down and do Savasana, and I can put my legs up the wall, and I can do things that feel good, and that will be helpful.”

Judith says, “Her posture has definitely improved and she’s gotten much stronger—more of an inner strength, a certain comfortableness in her body.” When Bonnie was having so much back pain, she wasn’t able to engage in life as she likes to. She seems happier now, Judith says. “I think that she feels empowered now that she has a tool that can help her control her pain. That’s one of the things that leads to depression, when people feel powerless in their life.”

“When I’ve been doing yoga regularly,” Bonnie says, “I stand better and I’m more aware of my body, my posture, and my movement.” Although she hasn’t practiced as regularly as she’d like, what Bonnie has consistently done is attend an annual week-long retreat that Judith teaches at the Feathered Pipe Ranch in Montana. Last summer at the workshop, Judith asked Bonnie how her back was, a subject that hadn’t come up all week. Surprised at first, Bonnie said, “My back? Oh yeah, my back!” They both laughed. “As long as I do my yoga,” Bonnie told her, “it’s fine.”

“There was a time when I thought I was destined for back surgery,” Bonnie says. “In fact, I made tapes of the entire season of Upstairs, Downstairs, because I figured that’s what I would do when I was recovering.” Those tapes have been collecting dust for more than a decade.