CHAPTER 12

CANCER

JNANI CHAPMAN is a registered nurse who teaches yoga for the Osher Center for Integrative Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, to people with cancer, heart disease, and other chronic illness. Her style of teaching and yoga therapy is based on the Integral yoga of Swami Satchidananda, with a strong influence from her time with T. K. V. Desikachar and his students. As an integrative medicine specialist, Jnani also practices acupressure and massage at UCSF, at the Commonweal Cancer Help Program in Bolinas, California, and the Smith Farm Center in Washington, DC. She worked for Dr. Dean Ornish’s Program for Reversing Heart Disease as a yoga/stress-management specialist from 1986 to 1999, and was the executive director of the International Association of Yoga Therapists from 1994 to 1997. Jnani certifies yoga teachers in adaptive yoga therapy for people with cancer and chronic illness through Yogaville, the Satchidananda ashram and teaching academy in Virginia.

JNANI CHAPMAN is a registered nurse who teaches yoga for the Osher Center for Integrative Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, to people with cancer, heart disease, and other chronic illness. Her style of teaching and yoga therapy is based on the Integral yoga of Swami Satchidananda, with a strong influence from her time with T. K. V. Desikachar and his students. As an integrative medicine specialist, Jnani also practices acupressure and massage at UCSF, at the Commonweal Cancer Help Program in Bolinas, California, and the Smith Farm Center in Washington, DC. She worked for Dr. Dean Ornish’s Program for Reversing Heart Disease as a yoga/stress-management specialist from 1986 to 1999, and was the executive director of the International Association of Yoga Therapists from 1994 to 1997. Jnani certifies yoga teachers in adaptive yoga therapy for people with cancer and chronic illness through Yogaville, the Satchidananda ashram and teaching academy in Virginia.

In the summer of 2002, when she was thirty-nine, Erin Brand noticed a lump in her breast about the size of a hazelnut. “I found it,” she remembers, “because there was actually pain. I sometimes sleep on my stomach and I noticed that I was kind of sore.” She wasn’t at all nervous about it because she knew that lumps that are tender are unlikely to be cancer, and because there was no history of breast cancer in her family. The fact that she’d had a baby at a relatively young age eliminated another known risk factor. She figured it was probably just a fibroid cyst, which are common and noncancerous.

Two weeks later, when she went to see her gynecologist, she had a needle aspiration of the lump just to be sure, though the doctor agreed it was probably just a cyst. Within a few days the call came, saying that they had found cancer cells. “They wanted me to meet with a surgeon the next morning,” Erin says. “It was pretty shocking.”

Three weeks later she had surgery to remove the lump. They also removed a so-called sentinel lymph node from under her arm but found no signs of cancer in it—an indicator that all the nodes are likely cancer free. The cancer turned out to be “an invasive tumor” less than an inch in size, surrounded in some of the nearby tissue by a less dangerous cancer, known as a ductal carcinoma in situ, or DCIS. With a small tumor and no involvement in the lymph nodes, Erin was surprised when her doctors recommended chemotherapy and radiation as well as the drug tamoxifen to block the female hormone estrogen from stimulating the cancer, but they felt that “because it was a high-grade, aggressive tumor, that was the best treatment to ensure that I wouldn’t have a recurrence.” Erin soon started the first of five rounds of chemotherapy.

In the middle of her second round of chemo, Erin began yoga. She’d never done it before but the hospital offered a gentle beginning yoga class for cancer patients, taught by Jnani.

Overview of Cancer

Cancer is probably the most feared disease in the modern world, although heart disease still comes first in the number of fatalities (approximately ten times as many women as from breast cancer, for example). Cancer of various varieties can be related to dietary, genetic, and environmental factors (see Chapter 4), and often more than one precipitating factor must be present for the disease to manifest. Subtle abnormalities in the immune system may also play a role in the disease. Abnormal cells with the potential for uncontrolled growth—the hallmark of cancer—form in everyone’s bodies with some regularity, but a healthy immune system normally gets rid of them before a tumor develops. While many members of the general public believe that stress can cause cancer, there is little scientific evidence to back this notion.

While the incidence of cancer continues to rise, survival rates have improved. Recent research published in The Lancet found that twenty-year survival rates were almost 90 percent for thyroid and testicular cancer, better than 80 percent for melanomas and prostate cancer, about 80 percent for endometrial cancer, and almost 70 percent for bladder cancer and Hodgkin’s disease. The study estimated a twenty-year survival rate of 65 percent for breast cancer, 60 percent for cervical cancer, and about 50 percent for colorectal, ovarian, and kidney cancers. These numbers are all considerably better than in the past, at least in part due to improvements in treatment. Even in cancers where the survival odds are lower, some individuals beat the odds, and are either cured or live far longer than doctors might guess.

How Yoga Fits In

A number of yogic practices may be helpful for people with cancer in reducing stress and managing side effects, both during chemotherapy and medical procedures and after. Although people being treated for cancer usually do not have enough strength to do a vigorous asana practice, the poses can be adapted to meet almost anyone’s needs. Restorative postures and simple pranayama exercises can be both energizing and relaxing, and require almost no physical effort. Meditation and guided imagery (such as found in Yoga Nidra) can be deeply relaxing and reduce anxiety. Some cancer survivors, once they are in recovery and have regained their strength, find volunteer work or other forms of service (karma yoga) to be useful in providing a sense of purpose and meaning.

Other yogic tools can help with pain, a frequent cancer symptom, particularly in its later stages, including relaxation, meditation, and breathing practices. The slower, deeper, more regular breathing that yoga facilitates can help you feel calmer and more energetic during the stressful period of being diagnosed with cancer and enduring treatment for it. Learning to cope with that stress can help you get through the ordeal, and may even improve your odds of survival.

Yoga philosophy has very practical implications for people with cancer. Yoga encourages you to listen to messages from your body (physical, emotional, and otherwise) and adjust your practice accordingly. This lesson can be extended to the rest of your life, too. If you tire after less work than you’re accustomed to, yoga would say honor that. Do less. Ask friends and family to step in to help out.

Yogic Tool: SANGHA. Yoga stresses the value of community (sangha), and a good cancer support group can provide this. There is evidence that involvement in a group may even increase your odds of survival, though follow-up studies have not confirmed the initial very positive findings. If you are interested, the key is finding one that meets your needs. Some are geared to providing information, others focus more on addressing emotional issues. Keep looking for a group that feels right to you, even if the first one you try doesn’t. If you aren’t drawn to support groups, however, please don’t think you need to be in one to give yourself the best shot at a cure.

At the time of a cancer diagnosis, many people find themselves taking stock of their lives. This is a form of self-study, or svadhyaya. People tend to ask themselves if they are spending their time and energy in ways that feel good to them. This line of inquiry helps in the yogic process of finding your dharma, figuring out why you are here, taking advantage of your strengths and interests to do something meaningful to you. This is something anyone can benefit from, but sometimes it takes a life-threatening diagnosis to slow you down enough to do this work. The silence facilitated by such practices as meditation often allows the inner wisdom that lies deep inside you to surface.

Since cancer inevitably brings up fears and worries about death, for those who are willing, spirituality is an important element of yoga as medicine. Jnani suggests that you simply try to “open a spiritual space,” to see things exactly as they are without trying to fix anything. “We are all intolerant of uncertainty,” she says. “Spirituality opens us to whatever happens. This paradoxically increases hope and faith,” which all by themselves have therapeutic benefit and can definitely improve the quality of your life. Jnani finds that an openness to spirituality can also improve the dying process.

Perhaps more than any other condition, cancer makes people feel like victims of a medical system over which they have no control. Things are done to them, often with very unpleasant side effects. Feelings of powerlessness are natural. By providing concrete steps you can take to feel better right now, and quite possibly increase your chance of long-term survival, yoga can change the whole psychology of the experience. In addition, people who feel betrayed by their bodies learn that they can still find relaxation and even joy in the body. In this space, yoga teaches, true healing can occur.

The Scientific Evidence

So far there are no scientific studies on whether yoga can improve the survival rate of people with cancer. But suggestive evidence comes from Dr. Dean Ornish, best known for his work using a comprehensive lifestyle program that included yoga for heart disease (see Chapter 19). Dr. Ornish has recently begun to study a similar approach for prostate cancer. The yoga portion of the program includes gentle asana, breathing techniques, and meditation. Early results are encouraging: When the blood serum of patients following the Ornish program was added to a line of prostate cancer cells in the laboratory, the serum inhibited their growth by 67 percent, compared to only 12 percent for controls. Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) levels, a marker of prostate cancer, decreased 3 percent in the patients following his program, while increasing 7 percent in subjects in the control group. Dean says they found a direct correlation between the degree of change in diet and lifestyle and the change in PSAs. In other words, just as in his earlier work on heart disease, the better people followed the plan, the better their results. “This may be the first randomized controlled trial showing that the progression of not only prostate cancer, but any cancer, may be affected through diet and lifestyle alone,” he says. “If it was true for prostate cancer, there’s a chance that it may be true for breast cancer as well.”

Researchers from the University of Calgary in Canada studied the effects of a seven-week program of Iyengar yoga on cancer survivors, primarily women treated for breast cancer. Once a week, the students took a seventy-five-minute yoga class, which consisted of gentle breathing in the pose Viparita Karani (Legs-Up-the-Wall), followed by fifty minutes of gentle asana modified to their needs and fifteen minutes of the Deep Relaxation pose Savasana (see Chapter 3). The students were encouraged to practice at home between classes. Compared to those in the control group, the yoga group had significantly less tension, anxiety, depression, confusion, anger, fatigue, diarrhea, and emotional irritability. The yoga group also showed improvements over the course of the seven weeks in their physical fitness and their heart rate, both when resting and after exercise. One surprising negative finding was the yoga students reported more pain, which the researchers speculated might be related to increased body awareness as a result of their practice, though this question needs to be researched more.

Preliminary findings are encouraging from a pilot study of Iyengar yoga for breast cancer survivors with marked fatigue conducted at UCLA. Eleven women with little or no prior yoga experience completed twice-weekly ninety-minute classes of poses thought to alleviate fatigue and depression, including restorative chest openers (see Chapters 3 and 15). The women showed what researchers call “strikingly large” improvements in fatigue going from 6.3 on a 10-point scale to 2.7. The women went from feeling fatigued 7 days per week to 4.6. These changes were still present on follow-up testing three months later. The women reported less pain, though the degree of improvement did not reach statistical significance. In addition, the women had significant improvements in depressive symptoms and in overall health.

A randomized controlled study conducted at the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center in Texas looked at the effects of a seven-week program of Tibetan yoga, a style not widely available in the West, on people with Hodgkin’s disease and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The regular practice of gentle physical movements and deep, mindful breathing resulted in significantly improved duration and quality of sleep, and less use of sleeping pills. The effects were still present three months after the program was completed. There were no significant improvements noted, however, in anxiety, depression, or fatigue.

Studies of mindfulness-based stress reduction, which includes mindfulness meditation and hatha yoga, have found that it can improve mood, fatigue, and feelings of stress in people with a variety of types of cancer. Guided imagery and relaxation have been found to result in potentially beneficial changes on measures of immune system function in women with breast cancer. A program of cognitive-behavioral therapy which included group support and instruction in relaxation techniques resulted in significantly lower levels of fatigue, depression, and confusion, and improved activity of cancer-fighting natural killer cells in patients with malignant melanoma, the most serious form of skin cancer. When the researchers followed up on the melanoma patients six years later, they discovered that only three out of thirty-four patients who had done the program had died, as compared to ten out of thirty-four in the control group.

A recent randomized controlled study done by Dr. Raghavendra Rao and colleagues at the Swami Vivekananda Yoga Research Foundation in conjunction with doctors at the Bangalore Institute of Oncology looked at the effects of yoga on ninety-eight women with stage II or III breast cancer who were undergoing conventional medical care including chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery. The yoga group did asana, pranayama, meditation, and chanting, among other practices. In addition to taking regular classes, they were asked to practice an hour a day at home. The control group received supportive counseling sessions. The researchers found large and statistically significant reductions in anxiety, depression, distress, severity and number of treatment-related symptoms, and toxicity of treatments, as well as major improvements in quality of life among the yoga group. The reduced toxicity of treatments may be particularly important since when side effects are too great doctors sometimes need to stop treatment or reduce doses in ways that may diminish its effectiveness. The same authors have collected sophisticated measures of immune function in both groups, but these results have not yet been published.

Jnani Chapman’s Approach

Jnani’s classes for cancer patients are gentle. Some students like Erin are relatively strong but are still feeling the effects of their cancer treatment. Others are weakened by the disease. Others, having completed their treatment and gone into remission, have the strength and endurance to take on a vigorous practice. So as not to exclude anyone, Jnani teaches practices that everyone in the room will be able to do, though some students will need to modify the poses to do them safely. In choosing asanas for people with cancer or with other major illness, Jnani places a premium on safety, in line with her training as a nurse.

Most of the practices are done sitting in a chair or on a mat on the floor next to the chair, but all of them, with the exception of tuning in at the beginning and meditation and Yoga Nidra at the end, involve movement. Usually, Jnani says, “We think the body will relax only when it is still, but I’ve found that slow, regular, and mindful movement of the body can induce a release of tension.” In the beginning stages she stresses this continual slow movement. If students hold poses at all, they are instructed to tune in to their bodies and to come out of the hold at the first sign of any tension. Her thinking in this regard has been heavily influenced by the approach of T. K. V. Desikachar (see Chapter 6).

When students are first learning the practice, Jnani errs on the side of being too gentle. She quotes Nischala Joy Devi: “If you give your students too much, you will give them indigestion. If you give them small morsels, you will increase their appetite.” To keep the level of fatigue down, Jnani stresses a model of “exert, rest, exert, rest.” Only when you’ve recovered from one pose should you move on to the next.

Here is a typical sequence of the poses and instructions Jnani teaches in cancer classes like the ones Erin attended.

Jnani begins each class with a “tuning in” process that she calls the Witness Practice, a step-by-step tour through the body. The idea is to check in with your physical body, with your mind and your thoughts, with your feelings and emotions. “Yoga teaches that by heightening your awareness—even of something painful—you can lessen its impact,” Jnani says. She encourages her students to include this kind of tuning in process at the beginning of their home practices as well.

EXERCISE #1. TUNING IN. Start sitting up straight in your chair, getting as comfortable as you can. If your feet don’t touch the floor, place a bolster beneath them so your legs can be passive and soft (figure 12.1). Let yourself relax as much as possible. When you are comfortable, begin the tuning in process:

1. Bring your awareness to the crown of your head and notice any physical sensations present in your scalp, in your face muscles, in your whole head. Whatever you notice, let it just be. In a similar fashion, draw your awareness to your neck, to your shoulders, and progressively through every part of your body. Jnani says, “You’re simply saying hello, as if you are taking inventory as a completely disinterested party.”

2. Bring your awareness to your emotional level. Notice if there are any feelings bubbling up for you that want to be acknowledged. Whatever’s present, let it be.

3. Bring your awareness to your thinking level. Begin to become aware of each thought that pops into consciousness. Notice any habitual patterns of thinking, any recurrent themes.

4. Bring your awareness to your energy level, noticing whether you are feeling tired or restless or some combination of the two, or if you are feeling completely relaxed and peaceful.

5. Bring your awareness to your breath, without trying to control it. How many seconds does a natural breath take to come in? How many seconds does a natural breath take to go out?

6. Bring your awareness back to your physical body, noticing, for example, which parts of your body are pressing against each other or the chair.

Next Jnani teaches a series of seated postures for the head, neck, shoulders, and upper back. She introduces this head and neck series because most people have tension, if not pain, and some range-of-motion limitation in their neck and shoulders.

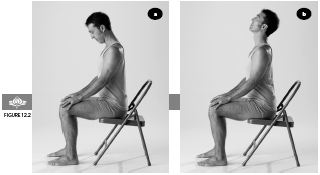

EXERCISE #2. VERTICAL HEAD MOVEMENT. Start with your head in a neutral position. As you exhale, let your chin drop down toward your chest (figure 12.2a). Then as you inhale, extend your chin gently up toward the ceiling (figure 12.2b). Continue at your own pace, using your breath, deeply and completely, and coordinating each steady movement with each inhalation or exhalation. Take long, slow exhalations and full, deep inhalations. Jnani stresses that how far you can go is less important than the attention you bring to each point along the way. Repeat this action several times.

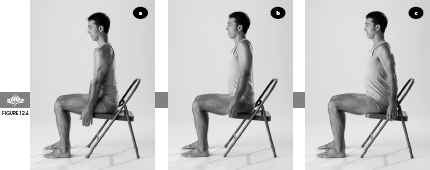

EXERCISE #3. HORIZONTAL HEAD MOVEMENT. Start with your head in a neutral position. As you exhale, turn your chin toward one shoulder in a horizontal line, for the full length of your exhalation (figure 12.3). As you inhale, bring your head to center. As you exhale, turn your head toward the opposite shoulder for the full length of your exhalation. Turn your head to each side a number of times, moving with your breath, and then return to center.

EXERCISE #4. HEAD TILTING. As you exhale, without rotating your head, drop your right ear down in the direction of your right shoulder for the full length of your exhalation (figure 12.4). Then inhale back up to center. As you exhale, drop your left ear down toward your left shoulder for the full length of your exhalation. Jnani says, “Even if the head only tilts a quarter of an inch to each side, that’s where the benefit is. So accept what is, and just witness it and the breath.”

EXERCISE #5. SHOULDER SHRUGS. As you inhale, shrug your shoulders up to your ears, for the full length of the inhalation (figure 12.5). As you exhale, press your shoulders down toward your feet. Continue at your own pace.

EXERCISE #6. FULL CIRCULAR ROTATION OF SHOULDERS. As you inhale, bring your shoulders forward in front of your chest (figure 12.6a), and continue inhaling as you raise them up toward your ears (figure 12.6b). As you exhale, bring your shoulders back behind your chest (figure 12.6c), and continue exhaling as they come all the way back down, making a full circle.

When you have finished these movements, begin to move your head, shoulders, and neck any which way, exploring their range of motion. Shake out your arms, and notice whether your shoulders feel different. Do you feel that you have more range of motion? If your shoulders feel tighter, you may have been trying too hard and should back off a bit next time.

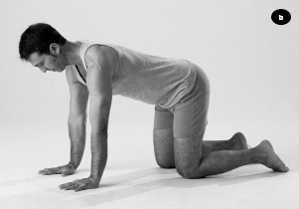

EXERCISE #7. CAT/TABLE. Kneel on all fours on a padded mat or a rug to protect your knees. Place your knees directly below your hips and your wrists directly below your shoulders. As you exhale, tuck your tailbone in and under and round your back, lifting it as you draw your abdomen up and in. Tuck your chin in toward your chest (figure 12.7a). Then as you inhale, flatten your back, extending your tailbone and the crown of your head in opposite directions (figure 12.7b). Repeat these actions several times, moving with your breath.

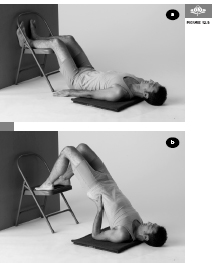

EXERCISE #8. MODIFIED SHOULDERSTAND. This pose gradually teaches the body to be upside down, and helps create strength and flexibility in the spine. Before doing the pose, be sure to remove any jewelry or clothing from around your neck. To set up for the pose, place a chair so that its back is against a wall. To come into the pose, lie on your back in front of the chair with your buttocks as close to the chair as comfortable and place your calves on the seat of the chair. Rest there with your arms alongside your body for atleast a minute (figure 12.8a). Then, when you are ready, turn your palms down as close to the body as is comfortable and bring your feet to the front edge of the chair. Push off with your feet as you press down on your palms and lift your buttocks off the floor. Place the palms of your hands on your buttocks for support (figure 12.8b). Never strain, and be sure your breath stays smooth and regular. Begin by holding the pose for ten seconds, eventually working toward thirty seconds.

EXERCISE #9. EXTENDED EXHALATION BREATH. Start by coming to an erect position on your chair, as you did for the tuning in process that began this practice. When you are settled, think back to the Witness Practice when you noticed the length of your inhalations and exhalations. In Jnani’s experience, most people who haven’t done yoga inhale for one to three seconds and exhale for one to two seconds (though you may be different). The idea behind this practice is to make the exhalation twice as long as the inhalation. Now place your hands on your belly. On your exhalation, draw your belly in toward the back of the chair, pushing out all the air, in a steady, even, controlled way for four seconds if possible. On your inhalation, expand your abdomen, and try to fill your lungs in two seconds. Depending on your comfort level in this exercise, you can raise or lower the amount of time you inhale and exhale, but try to keep the 1:2 ratio (figure 12.1).

EXERCISE #10. MEDITATION. Sitting in an erect position on your chair, close your eyes and let yourself settle in. Then either find a focus (see below) or simply watch your breath. Let the breath come and go without trying to control it, and draw your awareness to the in breath and the out breath. After a few minutes, very slowly begin to bring your focus back into the room. As you feel ready, let your eyes open (figure 12.1).

One question you may have about meditating is where to place your focus. With beginning students, Jnani often suggests following the breath as it moves in and out. For people who are more visual, focusing on an image such as a candle or a star may feel better. People who respond more to sounds may want to concentrate on a mantra, a syllable or phrase to repeat silently. The mantra could be in Sanskrit, or it could be an English word like “one,” “love,” or “peace.” If you are religious, repeating a phrase from your faith works well, as Harvard Medical School’s Dr. Herbert Benson recommends.

One question you may have about meditating is where to place your focus. With beginning students, Jnani often suggests following the breath as it moves in and out. For people who are more visual, focusing on an image such as a candle or a star may feel better. People who respond more to sounds may want to concentrate on a mantra, a syllable or phrase to repeat silently. The mantra could be in Sanskrit, or it could be an English word like “one,” “love,” or “peace.” If you are religious, repeating a phrase from your faith works well, as Harvard Medical School’s Dr. Herbert Benson recommends.

Jnani says that what is commonly called meditation is really an exercise in concentration. With focus, the mind may sometimes drop into a state of meditation. However, it is the nature of the mind to wander, so don’t beat yourself up if you continually lose your focus and need to bring your mind back. That happens to everybody. Jnani cites Dr. Benson’s research on meditation, which found that the physiological benefits of the practice come even to people whose subjective experiences were that they weren’t doing a good job of it.

EXERCISE #11. YOGA NIDRA. Following is a relatively short version of this yogic form of guided imagery, which Jnani based on the teachings of Swami Satchidananda. Yoga Nidra (see Chapter 3) can be useful to cancer patients, especially those feeling a lot of stress, because, as Jnani puts it, “It’s moving a person from the physical level of reality to deeper and deeper levels.” Jnani recommends that you practice Yoga Nidra lying on your back, either with soft pillows under your knees, or if it is more comfortable for your back, with your feet and calves resting on the seat of a padded chair.

Lie on your back and allow your legs to rest comfortably on the prop. Use a neck roll or pillow under your head if needed for comfort. Extend your arms out to the sides, with your palms up. You can rest the hands on small pillows if that feels better. Then settle in to let your body relax as much as possible.

Inhale deeply, hold the inhalation, and lift your limbs an inch or so off the ground, and squeeze all of the muscles in your body, including your face muscles, buttocks, and abdominal muscles. When you need to exhale, drop your limbs back to the beginning position and relax all of your muscles. Repeat this sequence two or three more times.

Allow your body to settle into the most relaxed position possible. When you are ready, begin the guided imagery portion of Yoga Nidra:

1. Bring your awareness through your body systematically, from your feet and legs up through your torso and trunk, your hands and arms, and your neck and head. Suggest to each part of your body that it relax and soften completely. Picture or feel a flow of relaxation moving upward. Practice this body scan for one minute.

2. Bring your awareness to the breath in its natural flow. Watch it come and go, without trying to change it. Continue observing your breath for one minute.

3. Bring your awareness to your mind and observe the thoughts that bubble into consciousness. When you notice a thought, simply let it come and let it go. Continue observing your thoughts for one minute.

4. Allow your awareness to rest in the center of your being, that center of radiant light, deepest peace, and fullest joy that yoga says is your own true nature. Rest there in stillness for five minutes.

When you are ready to come out of Yoga Nidra, please be slow and mindful. Begin by bringing the awareness back to your breath in its natural flow. Use your imagination to invite any quality of healing you desire to come in with the breath and to radiate to every cell in the body. Invite harmony and balance, patience and perseverance, peace and joy to every cell, every muscle, every tissue, every organ, and every system in your body. Slowly begin to wiggle your fingers and toes, roll and stretch your arms and legs, and gently help yourself up to a seated position.

In addition to the practices described above, Jnani often teaches her students with cancer such postures as modified Sun Salutations and gentle spinal twists. Alternative nostril breathing is a relaxing pranayama that she also finds very helpful. Jnani also teaches the Humming Bee Breath, Bhramari (see Chapter 1). Realizing that not all elements of the yoga program she teaches will appeal to all students, Jnani suggests her students follow their intuition in deciding which practices to stay with. She quotes her late guru, Swami Satchidananda: “Be unwilling to let go of your peace for anything. If something doesn’t resonate with your experience, let it go.”

Contraindications, Special Considerations, and Modifications

Both cancer itself and its treatment can lead to profound fatigue. It is therefore essential not to overdo your yoga practice. For patients undergoing chemo, Jnani believes that quick changes in posture are not advisable. Her experience is that most injuries happen when people combine movements such as lifting and twisting at the same time. She will only add more complicated poses that combine different movements once she is sure the student has gained awareness and ease with the simpler actions. Some asana practices could lead to fractures in people whose cancer has spread to the bones and weakened them in the process. Since Jnani’s approach is gentle and places the highest priority on injury prevention, fractures have not been an issue, but they could be in more vigorous styles of yoga. While not opposed to the kind of strenuous classes that have become the norm in health clubs, Jnani urges caution, even for those whose bones are strong. “These classes can help improve strength, muscle tone, flexibility, and cardiovascular conditioning,” she says, “but for people who are already somewhat depleted by their medical condition, these classes could make things worse.”

In addition, for anyone at risk of lymphedema, vigorous asana practice—particularly “hot yoga” often done in rooms heated to more than 100 degrees Fahrenheit—is contraindicated. Lymphedema is a frequent complication of treatment for breast cancer, especially if the lymph nodes under the arm are removed. Symptoms include pain and swelling of the affected arm, though in other cancers the problem can be in the legs. There is a high risk of infection, and wounds may be slow to heal. In women with breast cancer and lymphedema, it may be necessary to prop up the arm during asana practice and wear a supportive wrap to prevent swelling. Caution should be the rule. Sudha Carolyn Lundeen, a Kripalu yoga teacher and three-time breast cancer survivor, recommends no stretching for a week after surgery and stresses that the rule of thumb should be to “do less.” She recommends when moving the arms keeping the elbows bent, to shorten the lever of the arms and exert less pressure at the fulcrum of the shoulder. Jnani suggests that when doing poses like Cat/Table, it’s best to keep the arm on the affected side elevated to avoid the swelling that can result from the force of gravity. To modify Cat/Table, put a chair in front of your body so you can place the arm on the affected side on the seat of the chair during the whole pose (figure 12.9a). To modify Downward-Facing Dog, you could substitute Standing Half Forward Bend (Ardha Uttanasana) with the arms on the wall (figure 12.9b) or on the back of a chair. Women with or at risk of lymphedema should consult a yoga teacher who has experience with this problem. It is much better to take steps to prevent lymphedema than to have to deal with it once the swelling has begun.

Because of her belief in the healing power of the improved oxygenation that comes with yogic breathing, Jnani does not teach breath retentions to her clients with cancer. “They need the oxygen,” she says. Jnani stresses that deep diaphragmatic breathing can help move lymph and theoretically improve immune functioning, but she warns that Skull Shining Breath (Kapalabhati) and Bellows Breath (Bhastrika) can increase fatigue and may not be appropriate for those who are seriously ill, already depleted, or taking multiple medications.

a) Cat/Table with affected arm on the seat of a chair

b) Standing Half Forward Bend against a wall

A Holistic Approach to Cancer

Dietary measures may be helpful in both preventing and treating cancer (see Chapter 4). For example, recent evidence suggests that it is the olive oil in the Mediterranean diet that helps protect women in that region from breast cancer, and women living in countries like Japan, where the diet includes a lot of soy products, also tend to have a much lower incidence of the disease.

Dietary measures may be helpful in both preventing and treating cancer (see Chapter 4). For example, recent evidence suggests that it is the olive oil in the Mediterranean diet that helps protect women in that region from breast cancer, and women living in countries like Japan, where the diet includes a lot of soy products, also tend to have a much lower incidence of the disease.

Depression is a common complication in people with cancer. Psychotherapy and antidepressant medication, in addition to measures like yoga and meditation, can improve mood and perhaps the prognosis (see Chapter 15).

Depression is a common complication in people with cancer. Psychotherapy and antidepressant medication, in addition to measures like yoga and meditation, can improve mood and perhaps the prognosis (see Chapter 15).

Even though cancer pain can be controlled in nine out of ten patients, one study found that more than half fail to get relief. One reason is that doctors sometimes don’t prescribe narcotics—the most effective pain relievers—out of the usually groundless fear that their patients will become addicts. Ask for them if you need them. According to pain experts, there is no such thing as a standard dose for narcotics. The doctor should keep increasing the dose until the patient is comfortable, as long as side effects such as nausea, constipation, and sedation don’t become unbearable. You (or your loved ones) may have to be assertive to get what you need.

Even though cancer pain can be controlled in nine out of ten patients, one study found that more than half fail to get relief. One reason is that doctors sometimes don’t prescribe narcotics—the most effective pain relievers—out of the usually groundless fear that their patients will become addicts. Ask for them if you need them. According to pain experts, there is no such thing as a standard dose for narcotics. The doctor should keep increasing the dose until the patient is comfortable, as long as side effects such as nausea, constipation, and sedation don’t become unbearable. You (or your loved ones) may have to be assertive to get what you need.

Controlled experiments have found that acupuncture can diminish pain after surgery for breast cancer.

Controlled experiments have found that acupuncture can diminish pain after surgery for breast cancer.

Acupuncture or acupressure on the point P6—located three finger breadths up from the wrist crease in the center of the wrist, between the two rope-like tendons palpable just beneath the skin—has been demonstrated to reduce chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting.

Acupuncture or acupressure on the point P6—located three finger breadths up from the wrist crease in the center of the wrist, between the two rope-like tendons palpable just beneath the skin—has been demonstrated to reduce chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting.

Massage can be a useful addition to treatment of cancer because it can reduce both pain and anxiety, and induce relaxation.

Massage can be a useful addition to treatment of cancer because it can reduce both pain and anxiety, and induce relaxation.

Lymph drainage massage may be particularly useful to both prevent and treat lymphedema associated with breast cancer and other forms of cancer. It’s best to try this approach as early as possible in your recovery.

Lymph drainage massage may be particularly useful to both prevent and treat lymphedema associated with breast cancer and other forms of cancer. It’s best to try this approach as early as possible in your recovery.

Modalities such as therapeutic touch, healing touch, and Reiki appear to improve quality of life in cancer patients.

Modalities such as therapeutic touch, healing touch, and Reiki appear to improve quality of life in cancer patients.

Although antioxidant vitamins might be useful in preventing some cancers (the jury is still out on this), it’s probably prudent to discontinue use while actively undergoing treatment, as they could interfere with the effectiveness of conventional radiation and chemotherapy. Fruits and vegetables and other foods high in antioxidants are fine.

Although antioxidant vitamins might be useful in preventing some cancers (the jury is still out on this), it’s probably prudent to discontinue use while actively undergoing treatment, as they could interfere with the effectiveness of conventional radiation and chemotherapy. Fruits and vegetables and other foods high in antioxidants are fine.

Herbal medicine can help control side effects due to therapy. Ginger, in the form of capsules, tea, or the fresh root, can relieve nausea. Marijuana is also effective for this purpose in people undergoing chemotherapy, as well as to stimulate appetite, but cannot be used legally in most places. Valerian can help with insomnia and anxiety, particularly when taken regularly. With her oncologist’s approval, Erin took Chinese medicinal herbs throughout her course of chemotherapy.

Herbal medicine can help control side effects due to therapy. Ginger, in the form of capsules, tea, or the fresh root, can relieve nausea. Marijuana is also effective for this purpose in people undergoing chemotherapy, as well as to stimulate appetite, but cannot be used legally in most places. Valerian can help with insomnia and anxiety, particularly when taken regularly. With her oncologist’s approval, Erin took Chinese medicinal herbs throughout her course of chemotherapy.

Erin started taking Jnani’s class when she was already two infusions into her chemotherapy, and “I just took to it right away.” Erin thinks her yoga practice played a major role in helping her go through chemotherapy with relatively few side effects. She lost all her hair, but she never experienced nausea, one of chemo’s most common and unpleasant side effects. Erin says, “I’m kind of my oncologist’s poster child, the shining star example of someone who was able to get through chemotherapy, pretty heavy-duty, and not suffer greatly.”

Now, even when Erin doesn’t do the stretching exercises, she does the breathing practice every day, usually when she first wakes up, and typically while still lying in bed. When time allows, she’ll go straight from that into meditation, which she also does lying in Savasana position (though Jnani recommends it be done sitting). When she does an asana practice at home, she does it to a gentle yoga tape that lasts twenty-five minutes. In addition, she often does a half dozen Sun Salutations before she leaves for her morning radiation treatment. The Sun Salutations are modified as Jnani had shown her, for example, bringing the knees down to the mat in Plank Position or Chaturanga (see Chapter 13).

Erin feels she has gained a lot of awareness of her body from her yoga practice. “It helped me learn to relax specific muscles in my body.” Her growing awareness extends to her breathing. “I would say that it crosses my mind at least twenty times a day. How am I breathing? Am I sitting in a way that I’m keeping a space open to take deep breaths? Am I breathing slowly? Certainly it’s become almost like a reflex that if something stressful is going on, I just start doing the deep breathing. I haven’t had too much trouble with insomnia, but the few times I’ve woken up in the middle of the night and couldn’t sleep, I did that, and it helped me get to a place where I could fall back asleep.” She adds that “the breathing really came in handy when I was getting the different procedures for the needle localization, prior to the surgery.”

Getting diagnosed and treated for cancer has involved a lot of emotional ups and downs. The practice that Erin finds most useful in this regard is meditation, which has helped her observe and move through her emotions. Just after being diagnosed, Erin had started doing “a little bit of guided imagery and meditation.” Erin says her hypnotherapist taught her to find a place of sanctuary in her own mind, a restful place, to be and feel safe, which she found very useful. Deep relaxation has also been important. “It really creates a place where you can go inward and kind of clear your mind and relax. Afterward my sense of well-being is so improved. I just feel relaxed, like everything is all right—a really calm, wonderful feeling.”

Erin feels that the many modalities she used during and after her cancer experience have worked synergistically to help her heal. She includes not just asana practice, the guided imagery taught to her by her hypnotherapist, and deep relaxation, but also acupuncture, Chinese medicinal herbs, and an art therapy workshop which functions much like a support group for her.

She’s also made changes in her diet, moving away from what she calls “‘white foods’—white rice, pasta, all those heavy carbs”—and including more fruits, vegetables, and whole grains in her meals. “I eat for the most part as though I’m vegetarian, although I don’t totally restrict myself.” It’s made a big difference, she says. She’s lost 20 pounds, down from 170 to 150, “and I feel really good.”

Indeed, Erin says she now feels better than she did before she got cancer. “I know it’s odd, but that’s absolutely true. I personally believe that you can turn it around to make it a positive experience—but you do have to stop and deal with this in a very direct way. Two days after I got the original phone call from my gynecologist saying that they found cancer cells, I woke up at home, alone, in my room, and I had this epiphany. I had this real will to do whatever it took.”

Before her cancer diagnosis, Erin had never been particularly drawn to alternative healing practices like acupuncture and yoga. What Erin particularly likes about yoga is that it can be tailored to the individual. If some practices don’t interest you, or are beyond your current capabilities, yoga still has plenty to offer. Even if all you can do is imagine a particular asana, Erin says, you’re going to benefit from it. “You only have to do what you can do.”