CHAPTER 14

CHRONIC FATIGUE SYNDROME

GARY KRAFTSOW began his study of yoga in India with T. K. V. Desikachar, son of the legendary Krishnamacharya, in 1974, while still a college student. Although Gary holds a master’s degree in psychology and religion, his desire is to demystify yoga and make it relevant to people in the modern world, including those who come to yoga because of a medical condition. The viniyoga approach he teaches is gentle, with slow, flowing movements always coordinated with the breath. The emphasis is on home practice with short sessions, say, twenty to thirty minutes a day, that most people can fit into their busy lives. Gary developed a twelve-week practice series for a study that found yoga an effective treatment for back pain, recently published in the Annals of Internal Medicine (see Chapter 11). He is the founder and director of the American Viniyoga Institute in Maui, Hawaii, the author of Yoga for Wellness and Yoga for Transformation, and conducts workshops and teacher trainings around the US and internationally.

GARY KRAFTSOW began his study of yoga in India with T. K. V. Desikachar, son of the legendary Krishnamacharya, in 1974, while still a college student. Although Gary holds a master’s degree in psychology and religion, his desire is to demystify yoga and make it relevant to people in the modern world, including those who come to yoga because of a medical condition. The viniyoga approach he teaches is gentle, with slow, flowing movements always coordinated with the breath. The emphasis is on home practice with short sessions, say, twenty to thirty minutes a day, that most people can fit into their busy lives. Gary developed a twelve-week practice series for a study that found yoga an effective treatment for back pain, recently published in the Annals of Internal Medicine (see Chapter 11). He is the founder and director of the American Viniyoga Institute in Maui, Hawaii, the author of Yoga for Wellness and Yoga for Transformation, and conducts workshops and teacher trainings around the US and internationally.

Janice Oldenberg (a composite of different students Gary has taught) was in her mid-thirties when she noted a gradual loss of energy. She described it to Gary Kraftsow as coming on after a two-week, low-grade fever and flulike illness that she couldn’t seem to shake. After many months of symptoms, her doctor ruled out other causes and she was finally diagnosed as having chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS). A friend at work had been a student of Gary’s for years, knew he’d had success with others suffering from CFS, and recommended Janice give it a try. Although she’d done some yoga at her gym in the past and liked it, she hadn’t stuck with it.

Janice holds a fairly high-level job, in an environment that is competitive, political, and mainly male. Because the office is understaffed, she works long hours. When she began her sessions with Gary, she ate mainly in restaurants, grabbing things on the run, and rarely cooking at home. She didn’t get much sleep, drank a lot of coffee, and sometimes went to her twenty-four-hour gym late at night to work out because she wanted to lose a few pounds. Gary describes her as being “mildly depressed, not having a lot of fun, and working too much.”

Janice’s home reflected how overworked she was. She admitted to Gary that there were piles everywhere, including research for work. To Gary, this reflected her state of mind. “There’s a psychological thing about not cleaning, or not being able to let go of things that accumulate, holding on,” which he links to the Ayurvedic concept of kapha, the constitutional type associated with inertia (see Chapter 4).

Overview of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

Chronic fatigue syndrome, which is also sometimes referred to as chronic fatigue immune deficiency syndrome (CFIDS), is a potentially debilitating disorder of unknown cause. CFS appears to affect multiple systems in the body including the nervous system, the immune system, and the hormonal system. When it first started getting public attention in the 1980s, some people felt it was related to infection with the Epstein-Barr virus, the same one that causes mononucleosis, but this theory has not been borne out by subsequent research; attempts to tie the disorder to other viruses or toxic exposures have also been inconclusive.

Because fatigue can be caused by a wide range of medical conditions, be sure to have a thorough evaluation by a physician before assuming your fatigue is related to CFS. Conditions like anemia, hypothyroidism, sleep apnea, and even cancer can cause fatigue, so doctors will often conduct a number of tests to rule these out. In women and the elderly, so-called vital exhaustion may be the only symptom of an impending heart attack (see Chapter 19).

Because fatigue can be caused by a wide range of medical conditions, be sure to have a thorough evaluation by a physician before assuming your fatigue is related to CFS. Conditions like anemia, hypothyroidism, sleep apnea, and even cancer can cause fatigue, so doctors will often conduct a number of tests to rule these out. In women and the elderly, so-called vital exhaustion may be the only symptom of an impending heart attack (see Chapter 19).

The most prominent symptom of CFS is overwhelming fatigue, often after even minimal exertion. The syndrome often strikes previously healthy individuals in the prime of their lives and typically starts with viral-like symptoms that just don’t seem to go away. Other common symptoms include low-grade fever, sore muscles, problems with sleep, difficulty thinking straight (sometimes dubbed “brain fog”), headaches, and sore throat. Because of the substantial overlap between these symptoms and those experienced by people with fibromyalgia, some speculate that the disorders may be related. The official criteria for the diagnosis from the Centers for Disease Control require severe fatigue that is not otherwise explained by another medical condition like cancer or depression, lasting for at least six straight months. Also required to make the diagnosis is the presence of four or more of the common symptoms mentioned above. It’s important to remember, however, that this definition was formulated for research purposes and that people may have the condition even if they don’t meet all the criteria.

Because there are no lab tests to definitively confirm CFS, some doctors doubt whether it’s a real illness. Many people have essentially been told it’s all in their head, that the real problem is anxiety or depression. While depression is common among people with CFS, being sick (and not being acknowledged as sick) may have made them depressed, and not the other way around. Indeed, the depression that characterizes CFS usually differs from that of clinical depression (see Chapter 15). People with the latter may feel tired but also often lack motivation, while people with CFS are often highly motivated and frustrated by the inability to do what they want. People with CFS find other activities they are still able to do pleasurable, whereas those suffering from clinical depression tend to find little pleasure in anything. Despite these differences, anyone with CFS who has signs of serious depression should seek professional help, and may benefit from psychotherapy and antidepressant medication.

One common cause of fatigue that doctors sometimes forget to consider is medications. Hundreds of drugs, from antidepressants to blood pressure medication, can cause fatigue, so be sure your doctor is aware of all the drugs you take, both prescription and over-the-counter. Sometimes reducing the dosage, substituting a different drug, or cutting out the medication entirely can solve the problem.

One common cause of fatigue that doctors sometimes forget to consider is medications. Hundreds of drugs, from antidepressants to blood pressure medication, can cause fatigue, so be sure your doctor is aware of all the drugs you take, both prescription and over-the-counter. Sometimes reducing the dosage, substituting a different drug, or cutting out the medication entirely can solve the problem.

How Yoga Fits In

Yoga can be helpful in CFS for a number of reasons. First of all, gentle asana practice stretches muscles and keep joints limber without straining the body the way that overly vigorous aerobic exercise can. Restorative yoga, breathing exercises, and other relaxation practices can usually be done no matter how tired you are, and can help rejuvenate you.

Although the cause of CFS may turn out to be infectious in nature, stress appears to play a role. Anecdotally, many people with the syndrome report burning the candle at both ends right up until the moment they crashed. These people may have been living with their stress-response system turned on most of the time, until their bodies finally said “enough.” Research shows that people with CFS often have abnormalities in what’s known as the HPA axis, which stands for the hypothalamus, the pituitary, and the adrenals, three organs that coordinate the release of stress hormones, including cortisol. Many, though not all, people with CFS have abnormally low levels of this stress hormone, as if their adrenal glands have weakened after years of working on overdrive. Yogis believe these people need restorative practices and deep relaxation before their strength can be built back up.

Whether or not stress plays a role in causing or predisposing you to CFS, having the condition can be very stressful, and stress can make matters worse. Since yoga is perhaps the best stress-reduction measure ever invented, it’s likely to provide benefit regardless of what causes CFS. And since the effectiveness of yoga tends to increase the longer you stay with it, yoga offers a path to steady, albeit gradual, improvement.

To keep up the hectic pace that may have contributed to their burnout, many people with CFS have become accustomed to ignoring their body’s messages about the need to slow down and rest. Like Janice, they may use caffeine or other stimulants to help override the body’s objections to their lifestyle. For people who are not used to listening to their bodies, the heightened internal sensitivity that the regular practice of yoga brings can be of particular benefit. The better you can assess your internal states and correlate them to how you feel later on, the better you’ll be able to gauge how your activities are affecting you (and feel justified in saying no to demands that you can reasonably predict will be too much). This applies to your yoga practice as well. As you gain awareness, you can recognize when you need to shift your practice away from what you usually do to something more restorative.

Specific yoga practices can be helpful for the sleep problems that are often an important contributor to CFS symptoms. CFS sufferers seem to have difficulty going into deep sleep, which scientists believe is when a number of restorative functions occur. Studies of longtime meditators have found that while meditating they exhibit brain wave activity which may serve some of the same restorative functions as deep sleep, and their ability to function does not appear to be as affected by the loss of a night’s sleep as nonmeditators are. Yogic practices such as asana and breathwork can also improve sleep (see Chapter 23).

Gary Kraftsow believes pranayama can play an especially important role in CFS. Speaking from his experience using pranayama, Gary says, “It seems to make the whole metabolic system function better, with increased immunity, better digestion, better sleep, more energy, more vitality, and the regulation of hormones. It seems to be a homeostatic equalizer, to balance everything, and make people feel better.”

Like meditation, many pranayama practices require little physical exertion. Gary tries to keep the pranayama practices he teaches fairly simple. “I don’t ask most people to do tremendous gymnastics with breath control. That’s for people who have time and interest, to go deeper into it. But for most people who are living in the world, it’s an adjunct to a healthy lifestyle, and fifteen minutes of conscious breathwork once or twice a day is enough. It doesn’t have to be complex ratios and fancy techniques.” The benefits, he stresses, come with repeated practice and consistency over time.

Some people with CFS believe their prognosis for a return to a more normal life is bleak, that there is little they can do to improve their situation. The self-examination that yoga encourages can help you be alert to that kind of negative and self-defeating thinking. Self-study, or svadhyaya, extends to examining your lifestyle, too. Are you living in a way that promotes health? Are you sleeping enough? Do you eat meals at regular times? Is your food nutritious? Do you balance work with play?

Yogis believe that finding your dharma, knowing what you should be doing with your life, can be vital to recovery from CFS. With self-study and greater sensitivity, you may come to realize that your job, relationship, or living situation isn’t right for you. The quieting of the mind that yoga facilitates helps you tune in to messages you may previously have been unable to hear due to the high level of background noise. What you do with that information is for you to decide. Yoga simply helps put you in touch with it.

Finally, there is the social aspect of yoga. Due to their exhaustion, many people with CFS may give up previously enjoyable activities, focusing whatever energy they have left on their job. Being with people, making new friends, and forging a relationship with a teacher can all help alleviate isolation. This is what yogis call sangha, community, and it can be a powerful tool for healing.

The Scientific Evidence

So far no controlled studies have examined the effectiveness of yoga for CFS. The best evidence to date comes from a two-year prospective study published in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. Dr. Arthur Hartz and colleagues at the University of Iowa asked 155 people with unexplained chronic fatigue which measures, both alternative and conventional, they were using to deal with their symptoms. The researchers then correlated the answers with changes in self-reported levels of fatigue, depression, and other symptoms after 6 and 24 months. Subjects had suffered from fatigue for an average of 6.7 years at the beginning of the study. Among the approaches the people tried during the 2 years the study lasted were herbs, dietary supplements, prescription drugs, lifestyle changes, and yoga. Much to the researchers’ surprise, when the subjects were quizzed at the end of the study, yoga proved to be the most effective approach of all, and the only one with statistically significant benefits. Of those practicing yoga, at both 6 and 24 months, 25 percent reported “substantial” improvement in fatigue compared to an average of only 8 percent of those who tried other interventions. Only 5 percent of those doing yoga noted a significant worsening in fatigue at 2 years, as compared with 10 percent of those who didn’t do yoga. Similarly, the only treatment that predicted an improvement in depressive symptoms at the end of 2 years was yoga.

Gary Kraftsow’s Approach

In evaluating clients, Gary says, “I draw heavily on what I call the Pancha Maya model which comes from the Taittriyha Upanishad.” Gary is referring to the yogic model that views each person as being made up of five layers or sheaths (see table 14.1), starting on the outside, with the body, and moving progressively inward to the layer of bliss.

| ENGLISH | SANSKRIT |

| The body | Annamaya |

| Energy | Pranamaya |

| The lower mind | Manomaya |

| The higher mind | Vijnanamaya |

| Bliss | Anandamaya |

Beginning with the body, the Annamaya, Gary finds that some people with CFS have neck, shoulder, or back problems, and these structural problems influence which asana he recommends. In Janice’s case, he designed an asana sequence to deal with his finding that she “had a hip problem, a chronic sacral strain that seemed like a congenital hip imbalance. Her left hip was hypermobile, and she had a lot of nonspecific hip pain.” Gary also tends to make a lot of lifestyle suggestions. With Janice, he recommended that she drink less coffee and get more sleep. He also suggested she modify the way she was exercising, and do her cardiovascular exercise in the mornings, when she was better rested, rather than after a full day’s work. He also suggested a more consistent schedule, since her gym workouts were rather erratic.

To address the layer of energy, the Pranamaya, Gary asks his patients questions related to their energy levels in the morning and the afternoon, and how restorative their sleep feels. “After that,” he says, “I go into Manomaya. One of the things I’ve noticed with chronic fatigue patients is that there’s often something that’s not happy about their lives. What I try to do is find things they’re interested in that will stimulate their interest, their motivation.” Janice, Gary discovered, loves to throw pots. “It’s very good for her, but she hardly ever had time to do it, so I encouraged that.” Since the Manomaya layer is related to education, he encourages his patients to learn as much as they can about their condition, and the relationship between their lifestyle and their condition. He wants them to understand how much exercise is good and how much is too much. If they have digestive problems, he tries to explain possible connections to their diet.

You may think you don’t have time to pursue interests that do nothing more than give you joy, but yoga teacher Ana Forrest finds they can be essential to healing. One of her students with CFS “desperately wanted to be a painter,” but she had children, and a husband who didn’t have a regular source of income. Before she collapsed she’d been the main breadwinner, so she had put her needs aside. Ana told her that painting every day was “part of your rehab. So it’s not like you do it only if you have time and everybody’s fed.” Although Ana felt it would be crucial to her eventual recovery, she says, “It was almost like she needed my adamancy around in order to have permission to do something as ‘unimportant’ as her dreams.”

You may think you don’t have time to pursue interests that do nothing more than give you joy, but yoga teacher Ana Forrest finds they can be essential to healing. One of her students with CFS “desperately wanted to be a painter,” but she had children, and a husband who didn’t have a regular source of income. Before she collapsed she’d been the main breadwinner, so she had put her needs aside. Ana told her that painting every day was “part of your rehab. So it’s not like you do it only if you have time and everybody’s fed.” Although Ana felt it would be crucial to her eventual recovery, she says, “It was almost like she needed my adamancy around in order to have permission to do something as ‘unimportant’ as her dreams.”

The next level Gary addresses, Vijnanamaya, “has to do with people’s values and direction in life, what’s important for them.” He tries to understand his students’ emotional makeup, in particular their patterns. Janice, he says, was overwhelmed with work. Quitting was always at the back of her mind. “When you’re in a job that you don’t like, and you are overworked, and you’re always thinking about quitting, it’s not embracing your life as it is. It’s the same thing if you are in a relationship, but always thinking about getting out.”

Finally, Gary tries to help his patients address the Anandamaya dimension. “I try to help them reconnect with sources of joy or nourishment, which may or may not have a spiritual flavor. Many people in our society don’t have a church or God, but everybody can find something that is joyful to them. I try to help them reconnect to that.”

Obviously, Gary’s therapeutic prescription goes far beyond asana and Pranayama. Knowing how busy Janice was, Gary tried to give her a home yoga practice that was doable, dividing it into two different short practices of about fifteen to twenty minutes. The first one, done in the morning right before going to work, was designed to be stimulating. He designed the evening practice to help her relax and unwind from the day, release tension in her neck and shoulders, and improve the quality of her sleep.

Gary used both pranayama and breath control in the asana practice to increase Janice’s “threshold capacity,” which he believes stimulates immune function. By threshold capacity, he means the duration of the various phases of breath, the inhalation, exhalation, and pauses in between.

Here are the sequences of poses and instructions that Gary provided for Janice.

THE A.M. PRACTICE

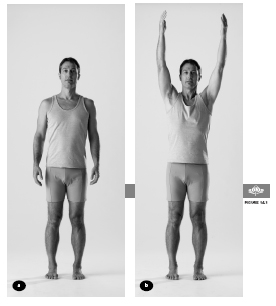

EXERCISE #1. EQUAL STANDING POSE (Samasthiti). From a standing position (figure 14.1a), inhale and raise your arms above your head (figure 14.1b). Hold your breath for a count of two. Then, on an exhalation, lower your arms slowly. Repeat for one more round. For a third and fourth round, hold your breath for a four count after inhaling. For a fifth and six round, hold your breath for a count of six.

As Janice got stronger, Gary substituted Mountain pose (Tadasana) for Equal Standing pose. In Mountain pose, you lift up on to tiptoes as you inhale and raise your arms overhead. As you exhale, simultaneously lower your arms and heels slowly.

Note that what Gary calls Mountain pose is different from the pose of the same name in other yoga traditions (this is true of many Viniyoga poses).

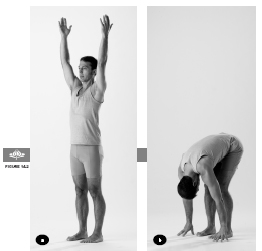

EXERCISE #2. STANDING FORWARD BEND (Uttanasana). Start by standing with your arms at your side. On an inhalation, sweep your arms out and up (figure 14.2a). Then on your next exhalation, lower your arms to the sides and bend forward into Standing Forward Bend, staying down for one complete breath (figure 14.2b). On your next inhalation, sweep your arms to the sides and then overhead as you return to standing. Repeat the round once more, staying in Standing Forward Bend for one breath. For a third and fourth round, take two complete breaths in the forward bend. For a fifth and sixth round, take three breaths in the forward bend. Gary told Janice if she was particularly tired, she should return her hands to her sides between rounds, rather than keeping them overhead.

Because Janice had a slightly kyphotic (rounded) upper back, Gary adapted the traditional pose and asked her to lift her chest and sweep her arms out to the sides when she was inhaling up out of the Standing Forward Bend (figure 14.2c). Having her arms at her sides allows her to use her shoulder blades to help coax more opening in her upper back. He instructed: “On the inhale, lift the chest slightly as if you were lying on your stomach doing Cobra—just slightly. It’s not a strong lift, just enough to create some movement in the upper back.”

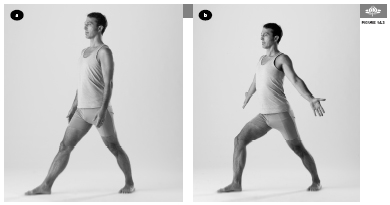

EXERCISE #3. WARRIOR I POSE (Virabhadrasana I). From a standing position, step one foot forward and the other back so that your feet are about three feet apart, with your hips square to the front (figure 14.3a). On an inhalation, bend your front knee and raise your arms as if they were the hands of a clock on four and eight, with the palms facing forward (figure 14.3b).

Hold the pose and your breath for a count of two then exhale back to the starting position. For the next round, inhale and repeat the pose with your arms at two and ten, palms facing forward(figure 14.3c), holding for a count of two, and then exhaling back to the starting position. On your last round, inhale and repeat the pose with your arms at “high noon,” palms facing each other (figure 14.3d), holding for two and exhaling back to the starting position.

In three versions of the pose, as you bend your knee, allow your shoulders to come forward of your hips, arching in the upper chest, without exaggerating the normal curve of the lower back. The shoulder blades move toward each other. Repeat all three versions holding for a count of four, after the inhalation. Then repeat all three versions of the pose holding for a count of six after the inhalation.

At no point during this sequence of nine repetitions should there be any tension in the breathing. If Gary noticed Janice was having any difficulty with the breath holds, he told her to back off. For example, instead of asking her to hold for a count of two, four, and six, he might make it one, two, and three. If you feel uncomfortable, you can also count a little faster. Just be consistent with the speed from repetition to repetition.

As she bent her front knee and raised her arms, Gary had Janice lean slightly forward from the hips to minimize the compression of the low back and to maximize the opening of the upper spine. To enhance the opening of the upper spine, he also asked her to bring her shoulder blades toward each other when she raised her arms. Both of these instructions were designed to help counter the rounding of her upper back.

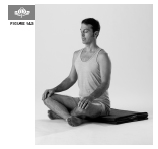

EXERCISE #4. SEATED REST. As an alternative to Deep Relaxation pose (Savasana), sit upright in a chair for three to five minutes (figure 14.4). Without making any effort to change it, simply notice your breath as it moves in and out.

EXERCISE #5. TWO-STAGE INHALE (Krama pranayama). Start by sitting on the floor in any comfortable seated position (figure 14.5). (Less flexible people can do this exercise sitting in a chair.) Stage one: inhale halfway for a count of four, expanding your chest, retaining the breath for a count of four. Stage two: inhale the rest of the way for a count of four, expanding your abdominal cavity, retaining the breath for a count of four. Exhale for twelve counts.

After you become comfortable with the two-stage inhale, you can practice the three stage inhale. Stage one: inhale in the chest for three counts and hold for three counts. Stage two: inhale into the upper abdomen for three counts and hold for three counts. Stage three: inhale into the lower abdomen and the pelvic floor for three counts and hold for three counts, then exhale on a count of twelve. This breathing practice is designed to be both energizing and calming.

THE P.M. PRACTICE

EXERCISE #1. STANDING FORWARD BEND (Uttanasana). Same as in the A.M. practice.

EXERCISE #2. REVOLVED TRIANGLE POSE (Parivrtta Trikonasana). Start by standing with your feet facing forward and about two and a half feet apart (figure 14.6a). On your exhalation, revolve your trunk, placing your right hand on the floor between your feet and extending your left arm straight up. As your arm extends up, turn your head to gaze down toward the floor(figure 14.6b). On your next inhalation, lengthen your left arm alongside your head and turn your gaze upward (figure 14.6c). On your next exhalation, return to your prior position, with the arm lengthening up and head gazing down. Then inhale back to your starting position. Repeat the pose three times on each side, alternating between sides.

EXERCISE #3. KNEELING POSE (Vajrasana). Start by kneeling in an upright position with your arms overhead (figure 14.7a). On your exhalation, bend at the hips and knees to come into Kneeling pose, sweeping your arms behind your back (figure 14.7b). On your inhalation, return to the upright position, lifting your arms back overhead. Repeat six times. Note that this pose resembles what is called Child’s pose in other traditions.

EXERCISE #4. SUPINE TWIST (Jathara Parivrtta). Start by lying on your back, with your knees bent in toward your chest and your arms out to the side along the floor (figure 14.8a). On an exhalation, lower your knees to your right side, toward the floor (figure 14.8b). Stay for one breath, then inhale and return to your starting position. Repeat to the left side. Repeat the entire sequence staying two breaths on each side, and then repeat the sequence again staying for three breaths on each side.

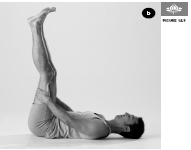

EXERCISE #5. WIND-RELEASING POSE TO LEG LIFT (Apanasana to Modified Supta Padangusthasana). Start by lying on your back, with your knees bent in toward your chest and your hands behind your knees (figure 14.9a). On an inhalation, straighten your legs, holding your hands behind the knees (figure 14.9b). Hold the leg lift for one breath, then exhale and release back to your starting position. For a second round, hold the leg lift for two breaths. For a third round, hold the leg lift for three breaths.

Note that Apanasana in the Viniyoga tradition resembles what is called Pavanmuktasana in other styles of yoga.

EXERCISE #6. RELAXATION POSE (Savasana). Lie on your back, with your hands and feet relaxed to the sides, and your eyes closed for three to five minutes.

EXERCISE #7. SEATED PRANAYAMA, lengthening the exhalation. Sit in any comfortable seated position. When you are settled, inhale to a count of three and then exhale to a count of eight. Do in this manner three more times. For rounds five to eight, exhale to a count of ten. For rounds nine to twelve, exhale to a count of twelve. This breathing practice, by progressively lengthening the exhalation, is designed to be deeply calming.

A practice that Gary often recommends to people with CFS who are also depressed is Chandra Bhedana pranayama. To do it, you inhale through the left nostril, hold the breath, and then slowly exhale through the right nostril. “There’s a kind of an emotional lift from the holding after the inhale, and a calming effect with a long exhale,” Gary notes. However, proper Chandra Bhedana technique—including the finger positions to partially block the nostril you are breathing in and out of while completely blocking the other nostril—is subtle and is best learned from a well-trained teacher.

In addition to asana and pranayama, Gary thought that yogic chanting would be therapeutic for Janice. But instead of teaching her chants to use in her home practice, he asked her to go to kirtans, public events where groups of people sing mantras in a call-and-response fashion, because he wanted to encourage her to develop her social life.

OTHER YOGIC IDEAS

A number of the restorative practices taught by B. K. S. Iyengar can be useful for fatigue in general and for CFS specifically (see Chapter 3). In particular a variation of Supported Bridge pose (Setu Bandha Sarvangasana) also called Cross Bolsters, is a gentle passive backbend than can help relieve fatigue. If you don’t have two bolsters, folded blankets or a block can substitute for the lower bolster. You can stay in this pose for five minutes or longer.

Contraindications, Special Considerations, and Modifications

Gary carefully adapts the intensity of the practice to the energy level of the student. “In an extreme case, the asana is very minimal,” he says. “It might be sitting on a chair, doing standing Virabhadrasana, and sitting back down on the chair, and then doing some breathing and then lying down and resting. That could be the whole practice. When they get stronger, the practice can be increased.”

In general, people who are fatigued should avoid strenuous postures like full backbends. They should also avoid long holds. It’s less tiring to move in and out of poses. Indeed, one reason why a Viniyoga practice may be particularly well suited to someone with CFS is because of its emphasis on constantly moving in and out of the poses, rarely holding a single pose for more than a few breaths. Other ways to modify a practice to minimize exhaustion include adding breaks between poses, interspersing Savasana, and using support like bolsters and blankets to make poses more passive and relaxing.

One of the biggest risks to people with CFS using yoga therapeutically is getting enthusiastic and taking on too much too soon, which can precipitate a flare-up of symptoms. The best plan is to start with modest activity, based on how you feel, then slowly ramp up over a period of weeks to months. It’s also wise to adjust how much you do on a daily basis, according to how you feel. If you’re feeling more exhausted than usual one day, scale back your practice and do gentler or more restorative exercises. Even some vigorous pranayama techniques may be too much if you are already feeling depleted.

Some people with CFS have a bothersome symptom known medically as postural hypotension; when you sit or stand up quickly, your blood pressure may not adapt fast enough and you may feel light-headed. Drinking plenty of fluids to remain well hydrated can help, as can being careful to make transitions slowly and deliberately both in daily life and in asana practice. If you feel light-headed in a pose, come out of it and relax in Savasana or another comfortable position with the head lower than the heart until you feel better. Gary has students prone to dizziness—including those with CFS, low blood pressure, and hypothyroidism (low thyroid)—avoid poses like Standing Forward Bend (Uttanasana), where the head hangs down, and substitute Utkatasana (Chair pose, seep. 164), moving from a standing position to a half squat. These symptoms may improve over time with steady practice. Some yoga teachers have found that the regular practice of inversions can also help with postural hypotension. For people who have little energy, supported versions of these poses such as Chair Shoulderstand (see Chapter 18) and Headstand hanging from ropes may offer similar benefits with little exertion.

A Holistic Approach to Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

There is no specific treatment for CFS in conventional medicine, in part because no one has figured out what causes the problem. Various treatments have been tried, including cortisone drugs, but these drugs have significant side effects and the results to date have been mixed at best.

There is no specific treatment for CFS in conventional medicine, in part because no one has figured out what causes the problem. Various treatments have been tried, including cortisone drugs, but these drugs have significant side effects and the results to date have been mixed at best.

A multipronged approach that includes mild exercise, attention to improving sleep, and cognitive behavioral therapy to learn coping strategies all appear to help to some degree.

A multipronged approach that includes mild exercise, attention to improving sleep, and cognitive behavioral therapy to learn coping strategies all appear to help to some degree.

People with CFS often find support groups helpful, though if members of the group are pessimistic about the chance of recovery, the experience can be counterproductive.

People with CFS often find support groups helpful, though if members of the group are pessimistic about the chance of recovery, the experience can be counterproductive.

Exercise can be a two-edged sword. Overdoing can backfire, causing greater fatigue, but doing nothing is even worse, since it leads to a general loss of conditioning, higher levels of depression and anxiety, and lower-quality sleep. To avoid a major flare-up in symptoms, try to carefully adjust your exercise intensity to your energy level in order to build stamina.

Exercise can be a two-edged sword. Overdoing can backfire, causing greater fatigue, but doing nothing is even worse, since it leads to a general loss of conditioning, higher levels of depression and anxiety, and lower-quality sleep. To avoid a major flare-up in symptoms, try to carefully adjust your exercise intensity to your energy level in order to build stamina.

Very low doses of tricyclic antidepressants appear to improve restorative sleep (stage 4), even in people with CFS who are not depressed.

Very low doses of tricyclic antidepressants appear to improve restorative sleep (stage 4), even in people with CFS who are not depressed.

Acupuncture is very safe and may reduce symptoms.

Acupuncture is very safe and may reduce symptoms.

Therapeutic massage and other forms of bodywork may reduce stress and alleviate pain.

Therapeutic massage and other forms of bodywork may reduce stress and alleviate pain.

Hydrotherapy including hot tubs, whirlpools, and gentle water aerobics may have similar benefits.

Hydrotherapy including hot tubs, whirlpools, and gentle water aerobics may have similar benefits.

In traditional medical systems like Ayurveda and traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), there are a variety of herbal tonics said to boost energy levels. Such herbs as ginseng, Siberian ginseng (which isn’t really ginseng at all, but an unrelated species), and ashwagandha can boost energy levels and are generally extremely safe. It may take two or three months to assess effectiveness. Rather than self-prescribe these treatments, it’s best to consult a practitioner of Ayurveda or TCM.

In traditional medical systems like Ayurveda and traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), there are a variety of herbal tonics said to boost energy levels. Such herbs as ginseng, Siberian ginseng (which isn’t really ginseng at all, but an unrelated species), and ashwagandha can boost energy levels and are generally extremely safe. It may take two or three months to assess effectiveness. Rather than self-prescribe these treatments, it’s best to consult a practitioner of Ayurveda or TCM.

The dietary supplement Coenzyme Q10, a natural constituent of the body’s cells, is safe and may boost energy.

The dietary supplement Coenzyme Q10, a natural constituent of the body’s cells, is safe and may boost energy.

Greater regularity in the timing of meals may be beneficial.

Greater regularity in the timing of meals may be beneficial.

Consumption of essential fatty acids, including the omega-3 fatty acids, found in flaxseeds and some seafood, may help, though the evidence is not consistent.

Consumption of essential fatty acids, including the omega-3 fatty acids, found in flaxseeds and some seafood, may help, though the evidence is not consistent.

Simple carbohydrates may raise insulin levels, quickly leading to a sharp drop in blood sugar and increased fatigue. Complex carbohydrates are a better bet.

Simple carbohydrates may raise insulin levels, quickly leading to a sharp drop in blood sugar and increased fatigue. Complex carbohydrates are a better bet.

Alcohol can help you fall asleep but should not be used for this purpose because it leads to disrupted, less restful sleep.

Alcohol can help you fall asleep but should not be used for this purpose because it leads to disrupted, less restful sleep.

Although it may be tempting to use caffeine for a temporary energy boost, it can make fatigue worse. Some find that a single cup of coffee in the morning doesn’t cause problems.

Although it may be tempting to use caffeine for a temporary energy boost, it can make fatigue worse. Some find that a single cup of coffee in the morning doesn’t cause problems.

In general, with these as with any suggested remedies, yoga says trust your own experience to learn what works for you.

In general, with these as with any suggested remedies, yoga says trust your own experience to learn what works for you.

Janice enjoyed the asana and pranayama practices Gary taught her, and also found she had an affinity for the Sanskrit devotional chanting he suggested she attend. As Gary had predicted, going to kirtans by performers like Krishna Das became a way for her to expand her social network.

Yoga, as narrowly seen, was only part of Gary’s prescription. He often has a lot of lifestyle negotiations with his students. One of the first things he asked Janice to do was to set aside a space in her home for a regular yoga practice. He felt that she needed to clean and organize her house as a way of clearing her mind. He tried to get her to be more consistent in her meal times, more conscious of her food, and more moderate in the quantity she ate. He says, “I also encouraged her to do more exercise in the daytime, rather than at three in the morning.” His main lifestyle suggestion was “to work less and have more fun. I encouraged her to create time so that she could do things that she enjoyed,” like throwing pots, hiking, and spending time on the beach on weekends. Janice eventually settled into a routine of going to the gym in the morning, instead of doing yoga, and doing an evening yoga practice, which was helpful to her sleep. If she didn’t have time to go to the gym in the morning, she did the short asana practice before going to work.

The pranayama work Gary did with Janice made her much more conscious of her breathing, and she eventually brought this awareness to her gym workouts, too. For example, Gary encouraged her to breathe deeply when using the elliptical exercise machine, and to standardize the number of steps she took per breath. This suggestion took hold. Once you start down that path, he says, the breathing really makes everything different, “much stronger and much more effective.” This process, of course, also brings yogic awareness to something that most people do mindlessly.

After working with Gary on and off for over two years, Janice is managing her condition much better. She takes better care of herself, and has lost some weight. She also has more friends and is more socially active, and she’s spending time out in nature on the weekends. Overall she’s less depressed, sleeps better, and has more energy. Although she still works too hard and has a love/hate relationship with her job, “she’s valuing her life more.”