CHAPTER 18

HEADACHES

Before becoming a yogi, RODNEY YEE danced professionally with the Oakland Ballet Company and the Matsuyama Ballet Company of Tokyo. One day in 1980, Rodney and a fellow dancer decided to try a class at the Yoga Room, an Iyengar yoga studio upstairs from the Berkeley Ballet Theatre where they were rehearsing, to see if it might help with their flexibility. Rodney remembers telling his friend afterward, “I can’t believe how good I feel.” Not only did his body feel fabulous, but he was touched in an emotional and spiritual way as well. A short time later, Rodney began to phase out his dance career in order to pursue yoga full-time. At the time, his family thought he was crazy and would never amount to anything because his earnings from teaching yoga were so meager that he needed to work as a waiter to pay the bills. Today Rodney is featured in over twenty yoga videos and has cowritten two books (with Nina Zolotow), Yoga: The Poetry of the Body and Moving Toward Balance. He teaches at the Piedmont Yoga Studio in Oakland, California, and internationally.

Before becoming a yogi, RODNEY YEE danced professionally with the Oakland Ballet Company and the Matsuyama Ballet Company of Tokyo. One day in 1980, Rodney and a fellow dancer decided to try a class at the Yoga Room, an Iyengar yoga studio upstairs from the Berkeley Ballet Theatre where they were rehearsing, to see if it might help with their flexibility. Rodney remembers telling his friend afterward, “I can’t believe how good I feel.” Not only did his body feel fabulous, but he was touched in an emotional and spiritual way as well. A short time later, Rodney began to phase out his dance career in order to pursue yoga full-time. At the time, his family thought he was crazy and would never amount to anything because his earnings from teaching yoga were so meager that he needed to work as a waiter to pay the bills. Today Rodney is featured in over twenty yoga videos and has cowritten two books (with Nina Zolotow), Yoga: The Poetry of the Body and Moving Toward Balance. He teaches at the Piedmont Yoga Studio in Oakland, California, and internationally.

Margaret MacIntyre (not her real name) developed migraines while working as a magazine editor in a fast-paced, deadline-driven environment. To make matters worse, she is, as she herself says, “the type of person who can make anything stressful.” She knows there is a strong connection between her stress levels and headaches. Putting it in Ayurvedic terms (see Chapter 4), she says, “I have a real pitta-vata constitution. I’ll get really caught up in thinking, stress myself out doing it, and end up with a migraine.” There is also a history of migraines in her family; both of her grandmothers had them.

“My migraines occur in the right frontal area. Once I get a migraine, without fail it will last for three days. There’s no variation in that, though I’ve found that there is a range of intensity. When it starts, it causes me to feel very drawn. I get a little sensitive to light, I get hypersensitive to smell. Sometimes I get a visual disturbance, too,” she says. “Things will become blurry. If I’m having a really bad one, I’ve got to go lie down. I can’t focus on things. It’s a complete audio-visual shutdown.”

Margaret has been a yoga practitioner for many years, gravitating primarily to active styles like vinyasa flow and Ashtanga yoga. Even so, her migraines persisted, tending to vary with her stress levels. One reason for her continued problems, she admits, was that she tended to push the edge in her yoga practice more than she should, doing advanced poses, intense pranayama exercises, and “high-energy” Sun Salutations. Before meeting Rodney and asking for his recommendations regarding her migraines, she had always avoided doing restorative poses in her home practice.

More than occasional headaches that occur at night or first thing in the morning may be related to depression, severe high blood pressure, or to a sleep disorder such as sleep apnea, and should be professionally evaluated. In rare cases, headaches are caused by life-threatening conditions. Ruptured aneurysms and strokes caused by hemorrhages can cause severe head pain, which may come on fairly suddenly. Contrary to what many people believe, brain tumors are rarely the cause of headaches. With tumors, other symptoms like balance problems, seizures, or muscle weakness will usually appear long before headaches. In general, doctors recommend that if you are having “the worst headache of your life” or one that is unlike any you’ve ever had before, you should seek prompt medical attention This is especially true if you are over the age of fifty.

More than occasional headaches that occur at night or first thing in the morning may be related to depression, severe high blood pressure, or to a sleep disorder such as sleep apnea, and should be professionally evaluated. In rare cases, headaches are caused by life-threatening conditions. Ruptured aneurysms and strokes caused by hemorrhages can cause severe head pain, which may come on fairly suddenly. Contrary to what many people believe, brain tumors are rarely the cause of headaches. With tumors, other symptoms like balance problems, seizures, or muscle weakness will usually appear long before headaches. In general, doctors recommend that if you are having “the worst headache of your life” or one that is unlike any you’ve ever had before, you should seek prompt medical attention This is especially true if you are over the age of fifty.

Overview of Headaches

There are dozens of possible causes of headaches. By far the most common are stress-or tension-related headaches, often associated with tightness in the muscles of the head and neck. People with tension headaches sometimes describe a feeling of pressure or dull pain encircling their head, like an overly tight bandana. In migraines, in contrast, pain is often on only one side of the head and described as pounding or throbbing in nature (which corresponds to the increase in pressure with each heartbeat). Migraines, despite their reputation, range in intensity from mild to incapacitating. Unlike tension headaches, they are often accompanied by nausea, vomiting, and a profound aversion to light and sound. Some people’s migraines are preceded by a brief period of visual disturbances (the aura), such as lights dancing in front of the eyes, or, much less commonly, changes to the sense of smell like Margaret sometimes experiences. Pressure in the sinuses, associated with a cold or allergies, or infection in the sinuses if they stay blocked too long, is another relatively common cause of headaches. Sinus headaches can also lead to migraines in people who are susceptible.

Specific yogic tools may be useful for sinus headaches. If you use a neti pot (see Chapter 4) to lavage your nasal passages with warm salt water early in a cold or at the first sign of nasal allergies, you remove excess mucus, allowing you to breathe more easily, and you may also be able to wash out viruses before they have a chance to colonize your nasal passages. Inflammatory cells may similarly be removed before they cause congestion. The neti pot may also help prevent blockages of the small openings to the sinuses, known as ostia, potentially heading off a full-fledged sinus infection. A study from Sweden’s Karolinska Institute suggests that the humming sounds like those made while chanting can improve ventilation of the sinuses. It appears that the resultant vibrations in nasal cavities help open up the ostia. Try chanting “Om,” holding the “m” a little longer than usual and tune in to the vibration in your nose and upper palate. The pranayama technique of Bhramari (see Chapter 1), where you hum a sound similar to the buzzing of a bee, also causes strong vibrations in the head and may help relieve sinus pressure.

Specific yogic tools may be useful for sinus headaches. If you use a neti pot (see Chapter 4) to lavage your nasal passages with warm salt water early in a cold or at the first sign of nasal allergies, you remove excess mucus, allowing you to breathe more easily, and you may also be able to wash out viruses before they have a chance to colonize your nasal passages. Inflammatory cells may similarly be removed before they cause congestion. The neti pot may also help prevent blockages of the small openings to the sinuses, known as ostia, potentially heading off a full-fledged sinus infection. A study from Sweden’s Karolinska Institute suggests that the humming sounds like those made while chanting can improve ventilation of the sinuses. It appears that the resultant vibrations in nasal cavities help open up the ostia. Try chanting “Om,” holding the “m” a little longer than usual and tune in to the vibration in your nose and upper palate. The pranayama technique of Bhramari (see Chapter 1), where you hum a sound similar to the buzzing of a bee, also causes strong vibrations in the head and may help relieve sinus pressure.

One underrecognized cause of both migraines and tension headaches is the use of pain relievers. The resulting “rebound headaches” can be worse than the ones you originally took the drugs to treat. The problem can result from taking even over-the-counter drugs like aspirin and ibuprofen as infrequently as twice a week. Drugs that combine pain relievers with caffeine and/or the sedative butalbital (e.g., Fiorinal, Esgic) are the ones most likely to cause rebound. The only way to get rid of rebound headaches is to stop taking pain relievers until the headaches go away. Since the withdrawal headaches can be bad, preventive therapy (see Chapter 18) may be advisable to get you through that phase.

The closer attention you pay to your headaches, the better you can help your doctor do his or her job. Many people with migraines, for example, are not properly diagnosed, but this is sometimes because they do not provide enough details to their doctors to allow for a diagnosis. The better you are able to describe your headaches—including where they are located, how long they last, the quality of the pain, what precipitates them, and what seems to make them better—the more you help the doctor make the correct diagnosis. This is important since therapies for various kinds of headaches differ. If you are not satisfied with the headache care you get from your primary care doctor, however, probably the best option, if it is available to you, is to consult a doctor specializing in headaches. These physicians can be found in the relatively few headache clinics that exist, in some pain clinics, and at some university hospitals. Even there, be sure to assess whether the doctor takes a comprehensive approach including factors like diet, exercise, and stress levels, or whether the strategy focuses mainly on drugs.

Yoga teacher and physical therapist Julie Gudmestad suspects that some tension headaches may be caused by yoga, specifically by arching the neck too much when doing backbends (top). A solution to this problem is to try to elongate your neck when bending backward, and to prevent the head from moving too far behind the upper spine. In doing Locust pose, for example, you might keep your gaze toward the ground, rather than lifting your head and trying to look straight ahead. In Cobra, you would keep your gaze straight ahead rather than looking up (bottom). Gary Kraftsow links headaches with the unconscious tendency of many yoga students to arch their necks back as they move into forward bends. If you find yourself doing this, try keeping your neck in a neutral position or let your head drop slightly forward instead.

Yoga teacher and physical therapist Julie Gudmestad suspects that some tension headaches may be caused by yoga, specifically by arching the neck too much when doing backbends (top). A solution to this problem is to try to elongate your neck when bending backward, and to prevent the head from moving too far behind the upper spine. In doing Locust pose, for example, you might keep your gaze toward the ground, rather than lifting your head and trying to look straight ahead. In Cobra, you would keep your gaze straight ahead rather than looking up (bottom). Gary Kraftsow links headaches with the unconscious tendency of many yoga students to arch their necks back as they move into forward bends. If you find yourself doing this, try keeping your neck in a neutral position or let your head drop slightly forward instead.

How Yoga Fits In

Since stress is a major factor in both tension headaches and in migraines, yoga can certainly play a role in prevention. Almost any form of yoga, including simple breathing techniques, can be effective in lowering stress levels. But a dedicated practice of yoga—particularly of meditation—may change the entire way you relate to people, situations, and events that are stressful to you, allowing you to respond more calmly, to feel less agitation. Incorporating regular Deep Relaxation (Savasana) into your yoga practice may similarly help you to be more resilient in the face of life’s inevitable challenges.

Yoga may also help with muscle tension in the back, neck, and head, which can cause or contribute to headaches. Yoga teaches that releasing the tight muscles improves blood flow to them, and can help relax the mind as well. There are a number of specific yoga postures that can help relieve tightness in these areas. From a yogic perspective, it’s not just tightness but muscle weakness and a failure to use muscles properly that can be a factor in headaches. Asana can help strengthen muscles, educate the body in how to use them, and improve bad postural habits like holding the head forward of the spine (see Chapter 2).

A steady yoga practice causes your ability to observe your internal environment to become more refined. As you become more aware of the way you use your body, you may begin to notice that you scrunch your eyes and forehead when you concentrate on something, or that you crook your neck to hold the phone next to your ear in a way that may be contributing to chronic muscular tightening and headaches (a phone headset is a great solution to this problem). With more subtle awareness, you may start to identify the signs of a headache earlier, sometimes even before the pain starts. You may notice, for example, gripping in your neck or the back of your head. Early detection can be essential for migraines since it’s usually much easier to prevent them or treat them in the initial minutes than after the pain is full-blown. By encouraging pratyahara, the ability to turn your senses inward and away from external stimuli, yoga provides respite from the kind of sensory overload of modern life that can trigger headaches (see Chapter 3). Because yoga is typically performed in a peaceful setting with dimmed lights, that too can facilitate relaxation. When the nervous system relaxes, muscles are more likely to release tension.

The awareness that yoga encourages also helps you become more sensitive to factors in the external environment that may be responsible for triggering headaches. Many experts suggest that headache sufferers keep a diary listing any headaches, their severity, how long they lasted, and possible precipitating factors. Possible triggers include various foods, bright lights (especially fluorescent), loud noises, skipped meals, sleep deprivation, air pollution, cigarette smoke, menstruation, menopause, estrogen taken either in birth control pills or after menopause, perfumes, changes in barometric pressure, either too much or too little sleep, and of course, stress. Among smokers, the more you smoke, the greater the headache problems tend to be. Looking back over your list may enable you to discern patterns that could help you avoid future attacks. This advice is entirely consistent with the yogic practice of self-study, svadhyaya.

Foods considered most likely to trigger migraines are listed below. If you’re unsure if a given food is triggering your headaches, it’s best to remove it from your diet for a couple of weeks and see what happens when you reintroduce it. If several foods are suspected, eliminate them all and reintroduce them one at a time. If eliminating all the leading suspects doesn’t improve your headaches, you may not have food triggers. But if your headaches do recur when you eat a food again, that’s evidence it may be a problem.

| Aged cheeses | Bananas, apples |

| Red wine, beer, and other alcoholic beverages | Citrus fruits |

| Dried fruits treated with sulfites (organic may be okay) | Eggs |

| Food made with monosodium glutamate (MSG) | Beans |

| Food containing artificial sweeteners like aspartame (NutraSweet, etc.) | Chocolate |

| Freshly baked bread | Wheat |

| Yogurt, sour cream, and other dairy products | Seeds, nuts, peanuts |

| Pickled foods | Cured or processed meats (e.g., bologna, pepperoni, ham) |

Yogic Tool: VISUALIZATION. Just by changing what you are thinking about, you can alter patterns of blood flow in the body. In the case of migraines, the objective is to reduce the amount of blood going to the head. Lie down in Deep Relaxation pose, with a pillow or folded blanket beneath the back of your neck and head. Close your eyes, breathe slowly and deeply through your nose, and imagine that your hands are immersed in warm water and that the blood flow is turning your palms rosy pink. As your fingers and hands heat up, imagine that your head is cooling down at the same time. Stay with these images and follow your breath for five to ten minutes or as long as you feel comfortable. This exercise can also be done in a seated position.

Yoga has been shown to reduce feelings of anger and hostility, and this could be useful for people with headaches. Dr. Robert Nicholson of Saint Louis University did a study which found that anger, particularly bottled-up anger, was a better predictor of headaches than anxiety or depression, two problems frequently linked to headaches. His advice sounds distinctly yogic: take deep breaths to quell your anger, try to figure out why you are angry deep down (self-study), let go of things beyond your control, and forgive. He points out that forgiveness will not change the past but neither will anger. Learning to let go of resentments can change you—and perhaps alter the likelihood of your getting a pounding headache.

The Scientific Evidence

There is scientific evidence that relaxation techniques and biofeedback can be effective for both tension and migraine headaches, lessening the duration as well as the frequency of attacks. Although these techniques are often offered outside of a yoga context, the approaches owe much to yoga. In a biofeedback session, for example, a patient might be taught to relax tight muscles in the face or neck, with instrumentation providing feedback directly from the muscles. After a while, the patient learns to induce the relaxation without the feedback. The process is all about facilitating awareness and conscious control of normally unconscious processes, and there’s nothing more yogic than that. Almost all relaxation techniques, including biofeedback, bring the patient’s awareness to the breath, another classic yogic tool. Dr. Seymour Diamond conducted two studies, published in the journal Headache, on patients with chronic headaches that hadn’t responded to conventional treatment. The combination of biofeedback, meditation, and relaxation techniques produced what he describes as “an excellent response.” Mindfulness-based stress-reduction programs that include asana and meditation have also been shown in studies led by Dr. Jon Kabat-Zinn to be an effective approach to chronic pain including headaches, improving function and lessening the need for medication (see Chapter 9).

S. Latha and K. V. Kaliappan of the University of Madras studied a yoga program that consisted of gentle asana and pranayama exercises, with twenty patients with either tension or migraine headaches participating. The randomized controlled trial lasted four months, and included two yoga classes a week in addition to home practice. Both the yoga and control groups continued to take their usual headache medications. Only the yoga group showed improvements, all statistically significant, in frequency, duration, and intensity of their headaches. The yoga group was able to decrease the amount of pain medication they took, while usage increased among the controls. In addition, the yoga group reported significant improvements in their levels of stress as well as their ability to cope with it.

In the largest study to date of yoga for chronic tension headaches, Dr. S. Prabhakar and colleagues divided eighty-five people into one group receiving yoga therapy and another on drug therapy. The primary drugs used were antidepressants for those who had depressive features in addition to their headaches, and Valium for those who manifested anxiety. The yoga practice consisted of asana, pranayama, and cleansing techniques (kriyas) done for forty-five to sixty minutes for fifteen to twenty sessions. Results were assessed at six weeks, six months, and one year later. Both the drug and yoga groups showed significant reductions in headache severity, frequency, and duration, though the changes were greater in the yoga group. Both groups showed improvements in anxiety and depression, though the results were again significantly greater in the yoga group. Only the yoga group showed less disruption of their social and work lives by headaches.

Rodney Yee’s Approach

Given the role of stress in many headaches, Rodney believes, any kind of yoga can be helpful—including the strenuous practice that Margaret had been doing. “A well-rounded yoga practice is sometimes the best thing.” By well-rounded, Rodney means a practice “that has something of everything—some standing poses, some inversions, some backbends, twists, forward bends, and some restoratives. It’s a practice that speaks to every part of the body.”

But since Margaret’s practice didn’t seem to be bringing her much relief from her headaches, Rodney reviewed it with her so he could see if there were any characteristics that might explain her lack of response. One problem that stood out to Rodney was that Margaret’s practice wasn’t well-rounded. She was putting almost all of her time into active, energizing practices, and none on restoratives. Margaret says that in “my personal practice, I almost never did those kinds of poses. I’m basically a prop minimalist. I had a bolster and some blocks and a strap and blankets, but I didn’t use them very much.” Rodney thought adding gentle restorative poses to her usual practice would help her achieve better balance. For more on restoratives, see chapter 3.

In talking to Margaret and watching her, he noticed that her eyes were very intense and that they didn’t blink or move very much. “They had a laser-beam quality. It’s like the pupils were fixated.” This quality seemed related to Margaret’s description of the pressure she felt building in her right eye when a migraine was coming on, as well as the fact that her eyes became dry then. He thought the dryness made sense because of how infrequently she blinks. The fact that she felt the symptoms more sharply in her right eye made sense, too, because she’d had toxoplasmosis ten years before, which had affected the retina in her right eye.

One of Rodney’s goals in working with Margaret was to get her “to be able to work intensely in the asanas, or in everyday life, without hardening her eyes so much.” Margaret says, “It kind of took me aback a little bit, but then I could see what he was talking about. I do express a lot of mental efforting through my eyes.” Rodney asked her to use her fingers, placed gently over her closed eyes, to feel any hardness in her eyes. He wanted her to become aware of the sensations, so that she could consciously work on softening them. The idea was to break down her old habit and replace it with a new one, so that she would associate work not with intensity in the eyes but with relaxation. He viewed the hardening of the eyes as an ingrained habit, what yogis would call a samskara.

As part of the work he did to help Margaret change this habit, Rodney asked her to practice the restorative poses below with her eyes covered with a head wrap. In addition to being deeply calming, he says that the head wrap is particularly good at facilitating awareness of what you are doing with your eyes. He also asked her to try her regular asana practice wearing the head wrap, when feasible, to heighten her awareness.

You can use any wide bandage for a head wrap. Many yogis, including B. K. S. Iyengar, who developed the technique of using head wraps in yoga practice, prefer Indian-made bandages that stretch but don’t contain elastic, because they think elastic tends to compress the head. Rodney feels that a plain Ace bandage, properly applied, works fine. To put on a head wrap (also sometimes called an eye bandage), start wrapping clockwise at the forehead, go down by the eyes, and then come back up (left, center). Don’t pull tightly; keep the bandage just lightly touching the eyes. Tuck the loose end to secure the bandage in place (right). In order to see when you move from pose to pose, you can roll up the bottom of the wrap, and then flip it back down when you are in the next pose.

You can use any wide bandage for a head wrap. Many yogis, including B. K. S. Iyengar, who developed the technique of using head wraps in yoga practice, prefer Indian-made bandages that stretch but don’t contain elastic, because they think elastic tends to compress the head. Rodney feels that a plain Ace bandage, properly applied, works fine. To put on a head wrap (also sometimes called an eye bandage), start wrapping clockwise at the forehead, go down by the eyes, and then come back up (left, center). Don’t pull tightly; keep the bandage just lightly touching the eyes. Tuck the loose end to secure the bandage in place (right). In order to see when you move from pose to pose, you can roll up the bottom of the wrap, and then flip it back down when you are in the next pose.

Here is the sequence of practices and instructions that Rodney provided for Margaret.

EXERCISE #1. LEGS-UP-THE-WALL POSE (Viparita Karani), five minutes or longer. Set up for the pose by placing a bolster or stack of blankets folded into long, thin rectangles parallel to the wall and approximately six inches away from it. To come into the pose, sit on one end of the bolster with your side near the wall (figure 18.1a). Then turn toward the wall and swing your legs overhead and onto the wall. Keeping your pelvis on the bolster, allow your shoulders and head to come onto the ground. Rest your arms either out to your sides or in cactus position (figure 18.1b). See chapter 3 for more on this and the following pose.

EXERCISE #2. SUPPORTED COBBLER’S POSE (Supta Baddha Konasana), five minutes or longer. Set up for the pose by placing a bolster on your mat to support your torso with a folded blanket or pillow at the end of the bolster to support your head. To come into the pose, sit a few inches in front of the bolster (not on it), with the soles of your feet together in Cobbler’s pose. Loop a strap around your sacrum and the tops of your feet, running it between your legs (not around your knees). Place blocks, pillows, or folded blankets under your thighs for support so that there is no tension in the groin area. Then slowly lie back over the bolster (see figure 18.2).

EXERCISE #3. CHAIR SHOULDERSTAND (Sarvangasana), five minutes or longer. To set up for the pose, place a bolster or two blankets folded into long, thin rectangles in front of a metal office chair. If you are using folded blankets, have the folded edge of the blankets face away from the chair. Place a folded yoga mat or blanket on the seat of the chair. To come into the pose, sit sideways on the chair. Hold on to the sides of the chair and swing your knees over the back (figure 18.3a). Keeping your legs over the back of the chair, slowly lean back until your shoulders reach the folded blankets or a bolster on the floor and the back of your head touches the floor. Then, thread your arms under the chair seat and hold on to the back legs of the chair. When you feel ready, bring one leg at a time to a vertical position (figure 18.3b). Please see pp. 275–76 for more on this pose and precautions to be aware of before attempting it.

EXERCISE #4. HALF PLOW POSE (Ardha Halasana), five minutes or more. To set up for the pose, fold two or more blankets into wide rectangles (as you would for regular, not chair, Shoulderstand) and stack them in front of the chair, with the folded sides facing the chair. If you are tall, you may also need to place blankets, a bolster, or other props on the chair seat (the taller you are, the more height you need) so that when you are in the pose, your thighs can be supported. To come into the pose, lie back on the blankets so your shoulders are supported and your head is on the ground just under the seat of the chair, if you have a chair that doesn’t have a bar connecting the legs in the front (or a chair from which the bar has been removed). If there is a support bar between the front legs, position the top of your head just in front of it (figure 18.4a). On an exhalation, roll back and swing your legs up and over so the tops of your thighs rest on the chair seat (or the props you have placed on top of it), your feet extend through the back of the chair, and your back is perpendicular to the floor. If your head is under the chair, position it so that the front edge of the seat (or the props on top of the seat) comes to the junction of your hips and thighs (see Chapter 25). Rest your arms around the chair legs with your elbows bent to 90 degrees, hands up toward the head, palms up (figure 18.4b). If you are tall you may need to turn the chair sideways (if the seat is level) or use a chair with its back removed (available from yoga suppliers, see appendix 2).

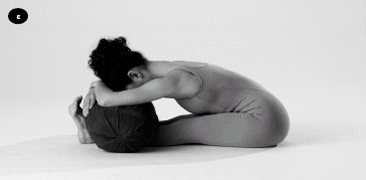

EXERCISE #5. ONE-LEGGED FORWARD BEND (Janu Sirsasana), with head support, two or more minutes on each side. Start by sitting with your legs extended in front of you. If your lower back rounds when your pelvis is flat on the ground, sit on one or more folded blankets. Bring the sole of your left foot near the inside of your right thigh and place a bolster or stack of folded blankets across your straight leg. On your inhalation, lengthen your spine. On your exhalation, fold forward at your hips so your torso comes over your right leg and your arms and head rest easily on the prop (figure 18.5). If your head does not reach the prop, increase the height of the prop or use the seat of a chair to rest your head. Repeat on the other side.

EXERCISE #6. SEATED FORWARD BEND (Paschimottanasana), with head support, five or more minutes. Set up as you did for the previous pose, keeping your legs straight, and placing the props across the tops of both legs. On your inhalation, lengthen your spine. On your exhalation, fold forward at the hips so your torso comes over your straight legs and your arms and head rest easily on the prop (figure 18.6). Again, if your head does not reach the prop, add more props or use a chair seat to rest your head(see Chapter 17).

Note: As an experienced yoga practitioner, Margaret can stay comfortably in this pose for several minutes, but less experienced students should stay only as long as they feel completely comfortable.

Although the primary focus of the plan Rodney devised was relaxation, he says that a secondary effect of many of the postures was to release muscular holding in the neck and shoulders. The supported forward bends and Chair Shoulderstand in particular are useful for this purpose.

EXERCISE #7. BREATH AWARENESS, with a brief pause after the exhalation, five to ten minutes. Sit in a comfortable upright position (figure 18.7). When you are settled, slowly inhale and exhale. Then briefly pause after the exhalation. (Rodney says the difference between a pause and a retention is basically a matter of degree. A pause might last only a second.) Continue at your own pace, staying relaxed and never forcing your breath.

In addition to prescribing this gentle breathing exercise, Rodney asked Margaret to discontinue her previous pranayama program. She had been doing advanced pranayama exercises with long retentions of the breath, and with fixed ratios of time spent inhaling and exhaling. Rodney believes that in most cases any type of breath retention or ratio breathing, unless you’ve had first-rate pranayama instruction and are very cautious, could contribute to migraines. He thinks vigorous breathing practices like Bhastrika and Kapalabhati are also potentially problematic. Even though Margaret’s personality always pushes her to do more, he says that since she is already stressed out, what she needs to do in her practice is less. “It’s obvious that she’s driven,” Rodney says. So he asked her, “Are you willing to give things up to get rid of these headaches?”

Another modification to Margaret’s practice that Rodney suggested was to follow Headstand, which yogis consider a “heating practice” and which she likes to do, with Shoulderstand, which is thought of as “cooling” but which she almost always skips. Shoulderstand can also often relieve tension in the neck muscles that develops from Headstand. Rodney thought it was interesting that just as Margaret had avoided restoratives, she had also avoided “anything that was more cooling.”

This understanding of heating and cooling practices comes out of Ayurveda (see Chapter 4). Ayurveda teaches that people often prefer foods, yoga practices, and lifestyle choices that increase their constitutional (doshic) tendencies. In other words, their preferences are often precisely those that will put them further out of balance. In Margaret’s case, her strong pitta, or fiery constitution, seemed to crave additional heat, when what she actually needed was cooling. Rodney told Margaret there were many signals, including her stress levels and headaches, that indicated she needed to relax more, calm her nervous system and relax her sense organs, especially her eyes.

Rodney also noticed that Margaret held a lot of tension in her groin area and lower abdomen. His sense was that “the energy is going up,” which in yogic thinking could contribute to headaches. “It’s a visual thing,” Rodney says. “Her thighbones were externally rotated and pushing forward.” John Friend talks about a similar finding in many women with infertility (see Chapter 22). Because Rodney felt there was not much downward release, he surmised Margaret might also have digestive problems, which she confirmed. What Rodney wanted to encourage in Margaret is what yogis call apana, a downward-moving force of prana or life energy in the body. Apana, yoga teaches, helps with bodily functions like digestion, urination, and menstruation. Rodney recommended that Margaret focus on releasing tension in her abdomen and grounding her legs in standing poses.

Focusing on the downward movement in breathing can contribute to headache relief. If asked to take a deep breath, most people lift their chests and actively recruit their neck and facial muscles, which ought to be relaxed. A better way to inhale, Rodney says, is to think of the lungs as being like a sponge which first needs to empty in order to absorb. Exhale as smoothly as you can, using your abdominal muscles to gently squeeze the air out. Then, rather than actively drawing breath in, let your belly relax with the natural downward movement of the diaphragm (see Chapter 10), allowing the body to relax and absorb breath.

Focusing on the downward movement in breathing can contribute to headache relief. If asked to take a deep breath, most people lift their chests and actively recruit their neck and facial muscles, which ought to be relaxed. A better way to inhale, Rodney says, is to think of the lungs as being like a sponge which first needs to empty in order to absorb. Exhale as smoothly as you can, using your abdominal muscles to gently squeeze the air out. Then, rather than actively drawing breath in, let your belly relax with the natural downward movement of the diaphragm (see Chapter 10), allowing the body to relax and absorb breath.

Contraindications, Special Considerations, and Modifications

While restorative poses can be very helpful in headache prevention, not everyone can simply relax into them right away. Rodney finds that many people “not only have stress, but also sort of a mental looping, where the mind keeps on obsessing over something. That kind of stress can bring on a headache.” The problem is that “sometimes the restoratives don’t stop the mind from going into this obsessive loop.” The solution may be to practice as Margaret now does, first doing an active asana practice to burn off steam, then moving into restoratives and more meditative practices.

If you have a severe migraine or a cluster headache—another type of debilitating headache which typically comes at the same time every day for weeks—you may need to simply lie down in a dark room and not attempt any yoga practices at all. During a less intense headache, it is probably best to avoid an active asana practice in favor of restorative work, or to do only gentle poses to avoid working too close to your “edge,” so as not to make matters worse. Inversions may also make symptoms worse, although B. K. S. Iyengar has been known to use them at times as part of the remedy. In general, supported inversions such as Chair Shoulderstand are thought to be preferable to unsupported inversions.

A Holistic Approach to Headaches and Migraines

There have been many changes in the drug treatment of migraines in recent years with the development of new medications (the triptans), such as Imitrex (sumatriptan) to treat, or if caught early enough, to eliminate the headaches entirely. These medications may help control migraines by constricting dilated blood vessels in the head, and they can be effective for severe tension headaches as well.

There have been many changes in the drug treatment of migraines in recent years with the development of new medications (the triptans), such as Imitrex (sumatriptan) to treat, or if caught early enough, to eliminate the headaches entirely. These medications may help control migraines by constricting dilated blood vessels in the head, and they can be effective for severe tension headaches as well.

Some triptans are available as a shot or in a nasal spray. Other medication including the anti-inflammatory indomethacin is available in suppositories. These forms are faster acting than tablets, and are particularly helpful for people too nauseated to keep medication down.

Some triptans are available as a shot or in a nasal spray. Other medication including the anti-inflammatory indomethacin is available in suppositories. These forms are faster acting than tablets, and are particularly helpful for people too nauseated to keep medication down.

Some migraine sufferers get good relief with over-the-counter medications like ibuprofen and naproxen, or with combination pain relievers that include some caffeine. Liquid forms of ibuprofen are absorbed into the system faster than pills and may therefore be preferable.

Some migraine sufferers get good relief with over-the-counter medications like ibuprofen and naproxen, or with combination pain relievers that include some caffeine. Liquid forms of ibuprofen are absorbed into the system faster than pills and may therefore be preferable.

Some patients need stronger pain relievers, including narcotics. When used appropriately, these drugs are generally safe and effective, with a low potential for addiction.

Some patients need stronger pain relievers, including narcotics. When used appropriately, these drugs are generally safe and effective, with a low potential for addiction.

Medications to prevent migraines include the tricyclic antidepressants, usually in lower doses than used for depression, beta-blockers like propranolol, which are typically used for high blood pressure, and medications originally targeted at epilepsy.

Medications to prevent migraines include the tricyclic antidepressants, usually in lower doses than used for depression, beta-blockers like propranolol, which are typically used for high blood pressure, and medications originally targeted at epilepsy.

Headache experts recommend considering preventive treatment if you’re getting two or more severe headaches a month that put you out of action for three or more days total, if you don’t respond to symptomatic treatments, or if you are using pain relievers so much that you’re experiencing rebound headaches.

Headache experts recommend considering preventive treatment if you’re getting two or more severe headaches a month that put you out of action for three or more days total, if you don’t respond to symptomatic treatments, or if you are using pain relievers so much that you’re experiencing rebound headaches.

A study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that preventive treatment with antidepressants for chronic tension headaches was much more effective if it was combined with stress-reduction techniques. Those who used medication and stress-reduction methods in combination were also more likely to be able to discontinue the drugs later on without a flare in headaches.

A study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that preventive treatment with antidepressants for chronic tension headaches was much more effective if it was combined with stress-reduction techniques. Those who used medication and stress-reduction methods in combination were also more likely to be able to discontinue the drugs later on without a flare in headaches.

Safe nondrug preventive measures besides yoga include the herb feverfew, vitamin B2, and magnesium.

Safe nondrug preventive measures besides yoga include the herb feverfew, vitamin B2, and magnesium.

Acupuncture appears to be an effective method of preventing migraines and is extremely safe.

Acupuncture appears to be an effective method of preventing migraines and is extremely safe.

Over-the-counter migraine remedies that contain caffeine can get rid of a headache, but regular consumption of the stimulant may make it more likely to get a migraine at times when the caffeine levels in your system are dropping, and may make headaches worse when you do get them.

Over-the-counter migraine remedies that contain caffeine can get rid of a headache, but regular consumption of the stimulant may make it more likely to get a migraine at times when the caffeine levels in your system are dropping, and may make headaches worse when you do get them.

A diet low in fat and high in complex carbohydrates can reduce the frequency, duration, and intensity of migraines.

A diet low in fat and high in complex carbohydrates can reduce the frequency, duration, and intensity of migraines.

Omega-3 fatty acids, found in such deep-sea fish as salmon and mackerel, and in flaxseed oil, have a similar benefit.

Omega-3 fatty acids, found in such deep-sea fish as salmon and mackerel, and in flaxseed oil, have a similar benefit.

If postural problems are part of the problem, in addition to yoga, instruction in the Alexander Technique may provide relief.

If postural problems are part of the problem, in addition to yoga, instruction in the Alexander Technique may provide relief.

A number of bodywork modalities can help with tension headaches including Trager work, shiatsu (acupressure), spinal manipulation, physical therapy, and various forms of massage including myofascial release techniques.

A number of bodywork modalities can help with tension headaches including Trager work, shiatsu (acupressure), spinal manipulation, physical therapy, and various forms of massage including myofascial release techniques.

Acupressure can be self-administered: press firmly on the hollow just below the bottom of your skull on both sides of the neck as you tip your head back. Alternatively, pinch the webbed space between the thumb and index finger of your left hand. Try either or both of these techniques, maintaining pressure for two or three minutes.

Acupressure can be self-administered: press firmly on the hollow just below the bottom of your skull on both sides of the neck as you tip your head back. Alternatively, pinch the webbed space between the thumb and index finger of your left hand. Try either or both of these techniques, maintaining pressure for two or three minutes.

Contrary to her expectations, Margaret enjoyed the restorative practice that Rodney recommended. “The head wrap is really profound,” she says, “very effective in making me feel very deeply drawn inward.” Her favorite pose of the sequence is Chair Shoulderstand. “I get this sense of my legs clicking into place, and a sense of relaxation that I’ve never experienced in any pose before.” In retrospect, Margaret sees that she had always avoided the restorative experience, because like a lot of driven people, she felt that she always needed to be accomplishing something. “I had to struggle with myself just to get used to the idea that it’s okay to spend this time.

“Rodney has asked me to do some subtle things, like draw the skin of my forehead down, rather than up, when I’m working with the head wrap.” (See Chapter 1 for more on this topic.) She says the difference was palpable. She’s also followed his advice about paying attention to her eyes, and to whether or not she’s straining, both on and off her yoga mat. Another suggestion she incorporated was to do her yoga practice without wearing her contact lenses, allowing her to relax her eyes even more.

Rodney’s program, which she enjoys so much that she does it nearly every day, has reduced her migraines from three or four a month, and twice that many when really stressed, to one or two. Even more impressive, this success came in spite of her moving, just after beginning the program, to another city to take another demanding editing job. Even though she’s extremely busy and anxious about the new job—circumstances that are exactly “the kind of environment that breeds my migraines”—she’s had many fewer than expected. “I think that’s pretty amazing.”