CHAPTER 19

HEART DISEASE

NISCHALA JOY DEVI says, “Before yoga, I realized the American dream.” Despite all the material advantages, however, she still wasn’t happy. She met her guru, Sri Swami Satchidananda, the founder of Integral yoga, in San Francisco in 1973 and connected with him immediately. She was working as a physician’s assistant in a cardiologist’s office at the time, but gradually became disillusioned with the narrow approach to healing found in Western medicine. When she moved to the guru’s ashram in Connecticut in 1979, she started to teach yoga to a number of seriously ill patients in its holistic health clinic. “It was a natural way for me to combine both parts of my life,” she says. A few years later, she met the physician, medical researcher, and author Dean Ornish, another disciple of Satchidananda. When he put together the Lifestyle Heart Trial, a groundbreaking study of a multifaceted program to reverse heart disease, Dean asked her to help design the yoga portion of the program. Nischala taught yoga to the participants as well as training the other yoga teachers, and subsequently served as Director of Stress Management. Nischala was also a cofounder with Dr. Michael Lerner of the Commonweal Cancer Help Program in Bolinas, California, a residential retreat for people with cancer that incorporates yoga, massage, and other healing modalities. She has gone on to write two books, The Healing Path of Yoga and The Secret Power of Yoga, and created and directs Yoga of the Heart, a yoga therapy training program for yoga teachers and health professionals working with people with life-threatening diseases. She lives in the San Francisco Bay Area and teaches internationally.

NISCHALA JOY DEVI says, “Before yoga, I realized the American dream.” Despite all the material advantages, however, she still wasn’t happy. She met her guru, Sri Swami Satchidananda, the founder of Integral yoga, in San Francisco in 1973 and connected with him immediately. She was working as a physician’s assistant in a cardiologist’s office at the time, but gradually became disillusioned with the narrow approach to healing found in Western medicine. When she moved to the guru’s ashram in Connecticut in 1979, she started to teach yoga to a number of seriously ill patients in its holistic health clinic. “It was a natural way for me to combine both parts of my life,” she says. A few years later, she met the physician, medical researcher, and author Dean Ornish, another disciple of Satchidananda. When he put together the Lifestyle Heart Trial, a groundbreaking study of a multifaceted program to reverse heart disease, Dean asked her to help design the yoga portion of the program. Nischala taught yoga to the participants as well as training the other yoga teachers, and subsequently served as Director of Stress Management. Nischala was also a cofounder with Dr. Michael Lerner of the Commonweal Cancer Help Program in Bolinas, California, a residential retreat for people with cancer that incorporates yoga, massage, and other healing modalities. She has gone on to write two books, The Healing Path of Yoga and The Secret Power of Yoga, and created and directs Yoga of the Heart, a yoga therapy training program for yoga teachers and health professionals working with people with life-threatening diseases. She lives in the San Francisco Bay Area and teaches internationally.

You might have thought that Ron Gross would have been an easy convert to the idea of using a yogic approach to heart disease because he is Nischala’s father-in-law. In reality, Ron was as deeply skeptical of yoga’s therapeutic potential as he’d been unhappy about his son Bhaskar’s decision to renounce the world and become a swami at the Satchidananda ashram years before. Bhaskar’s time at the ashram ended when he and Nischala, whom he met there and who had also taken the path of renunciation, came to the realization that they could best be of service by returning to the outside world. They are now married.

A hard-charging businessman, Ron describes himself as “a typical type A. I get up early and work late.” During Ron’s commute to the office, he says, “I used to get stomach pains because I was so angry that the traffic was moving so slowly going through the tunnel.” He’d also get “stomach muscle pains” in real tough business negotiations. “Sometimes,” he says, “I’d lose my cool, blow up, start yelling and screaming, pick up and walk out of the negotiations. That might have been good for the negotiations, but it wasn’t very good for me.”

Ron’s other risk factors for heart disease besides his type A personality include a family history. His father died of a heart attack at age fifty-two. Ron’s total cholesterol was high, around 230, his HDL or “good” cholesterol was dangerously low, in the mid-20s, while his LDL or “bad” cholesterol was almost 200, much too high. He did have some factors in his favor, however. He wasn’t a smoker, didn’t have diabetes or high blood pressure, and had exercised regularly his entire adult life. At 5' 8" and 165 pounds, he wasn’t more than a few pounds over his ideal weight.

Ron’s first indication of heart disease came at the age of sixty-eight. He was swimming to get in shape for an upcoming diving trip when he noticed that he was uncharacteristically out of breath. His doctor ordered an angiogram and discovered his right coronary artery was about 90 percent blocked. Ron had an angioplasty immediately. “The doctor said if I had gone on my scuba-diving trip, they’d have brought me back in a box, because I would never have survived. But I felt pretty good after the angioplasty,” good enough to continue being active. Though he gave up diving, he continued his tennis game. He also started to eat a low-fat diet.

“Fast forward to two years later. I was walking across the street, maybe half a block, I have to stop and rest. I was out of breath. Everything was back to where I was before the original angioplasty. It looked like I’d have to go in for another angioplasty.” Nischala was teaching the Dean Ornish program at the time, which begins with a week-long residential retreat, in which students walk, attend group meetings, eat a vegetarian diet that derives less than 10 percent of its calories from fat, and are taught yoga postures, breathing techniques, meditation, and imagery. Nischala said, “If you take the week-long program, and you don’t feel better, I’ll pay for it.

“Of course, I had no money at the time,” she says, but based on her experience, it seemed like a pretty safe bet.

Overview of Heart Disease

Heart disease is the number one killer in the modern world, and contrary to popular notions, it is not just men who are affected. While men do tend to come down with symptoms earlier than women, heart disease is the number one cause of death for both sexes, and more women than men suffer heart attacks.

In predicting heart attacks, doctors tend to focus on risk factors like smoking and elevated cholesterol, but science has uncovered strong evidence for other possible contributors. Type A behaviors, which are characterized by anger and hostility, a focus on achievement, and a sense of urgency about time—exactly the behaviors Ron describes have been strongly linked to heart attacks in a number of studies. Other psychosocial factors include job dissatisfaction, loneliness, and an unhappy marriage. Overweight is not a huge independent risk factor but is problematic in that it contributes to type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, and elevated levels of a type of blood fat known as triglycerides, all of which are strongly linked to heart problems. There appears to be an unhealthy synergy involving risk factors for heart disease. They don’t just add up—they multiply. People with four or five bad ones may be at fifty times the average risk for a heart attack.

When considering medication to lower your cholesterol, keep in mind that there’s generally no rush. Cholesterol wreaks its damage over decades. Whether you start a drug today or six months from now usually won’t make much difference. My advice is to give diet, exercise, and nondrug therapies a chance to work before committing to what may be a lifelong regimen of medication.

When considering medication to lower your cholesterol, keep in mind that there’s generally no rush. Cholesterol wreaks its damage over decades. Whether you start a drug today or six months from now usually won’t make much difference. My advice is to give diet, exercise, and nondrug therapies a chance to work before committing to what may be a lifelong regimen of medication.

In recent years, researchers have begun to focus on inflammation as another major factor in heart disease. Supporting this notion is the higher incidence of heart disease among people with inflammatory conditions ranging from rheumatoid arthritis to gingivitis (inflamed gums). Recently, some doctors have been advocating measuring the level of C-reactive protein (CRP), a measure of inflammation, to assess heart attack risk. That inflammation and heart disease are associated isn’t news to many yogis and those trained in Ayurveda. What Western doctors call a type A personality has a lot in common with the constitutional type that Ayurvedic medicine calls pitta (see Chapter 4). Pittas tend to be intense, fiery, prone-to-anger overachievers. If their fire burns too hot, Ayurveda says, it predisposes them to heart attacks and other inflammatory conditions, and for thousands of years Ayurvedic practitioners have used diet, lifestyle recommendations, herbal remedies, and other treatments to try to cool down the flames.

Women often don’t have the so-called classic symptoms of heart disease—classic, as it turns out, for males, who until recently were the only ones studied. The classic heart attack symptom in men is crushing chest pain that radiates to the shoulder, jaw, or arm. Women may have milder pain in the chest or abdomen. Often their most prominent symptom is fatigue and a general feeling of weakness. An underrecognized warning sign, which may begin months before a heart attack strikes, is an extreme form of burnout known as vital exhaustion, characterized by excessive fatigue and lack of energy, increased irritability, and feelings of demoralization. Both sexes may have nausea, sweating, or shortness of breath.

Women often don’t have the so-called classic symptoms of heart disease—classic, as it turns out, for males, who until recently were the only ones studied. The classic heart attack symptom in men is crushing chest pain that radiates to the shoulder, jaw, or arm. Women may have milder pain in the chest or abdomen. Often their most prominent symptom is fatigue and a general feeling of weakness. An underrecognized warning sign, which may begin months before a heart attack strikes, is an extreme form of burnout known as vital exhaustion, characterized by excessive fatigue and lack of energy, increased irritability, and feelings of demoralization. Both sexes may have nausea, sweating, or shortness of breath.

How Yoga Fits In

Because the stress response affects the heart in a number of harmful ways, yoga’s proven ability to fight stress is a big part of the explanation for how yoga benefits people with heart disease. Stress hormones raise the blood pressure and heart rate, putting added strain on the heart and increasing its need for oxygen. Periods of either physical or mental stress can be particularly dangerous for someone with a heart whose blood supply is compromised by fatty blockages, though evidence suggests that stress can induce a heart attack in the absence of blockages by causing spasm in a coronary artery. Stress hormones also induce changes that cause the blood to clot more easily. Doctors now believe that heart attacks often happen when a clot gets lodged in an artery that is already partially narrowed. The stress hormone cortisol is known to increase both eating and the laying down of fat in the abdomen. Intra-abdominal fat can increase the body’s resistance to the effects of insulin, raising blood sugar and further increasing the risk of heart disease.

Yoga’s ability to lessen anger may lower the risk of a heart attack. “Anger is a very strong emotion,” Nischala says. “It takes at least three hours physiologically for the body to get back in balance, to the place it was before an angry episode—and many heart attacks happen within three hours of an angry episode.” She says that anger was very common among the participants in the Ornish program, and most knew and admitted it.

The regular practice of yoga seems to lessen anger by fostering greater psychological equanimity, increasing feelings of compassion for others, and increasing the sense of gratitude. Yoga also helps people achieve a heightened awareness that puts the minor annoyances of life in a larger perspective, so that they are less likely to respond to the traffic jam or the difficult situation at work with the kind of agitation Ron Gross described. And yoga provides specific tools, such as breathing techniques, which can dampen the first sparks of anger and prevent them from being fanned into an inferno.

Yoga as a form of physical exercise, if done vigorously enough, can raise the heart rate into the aerobic range, potentially lowering the risk of a future heart attack (but see below for safety considerations). Even pranayama (yogic breathing) alone has been shown to improve cardiovascular conditioning. The improved efficiency of lung function and better oxygenation that comes with regular yoga practice means that more oxygen reaches the heart muscle even in instances where partial blockages compromise blood flow. Yoga can help people lose weight not just because asana burns calories, but because lower levels of stress hormones lessen appetite, and because practitioners bring conscious attention to what and how they eat (see Chapter 27).

Yoga is also a good antidote to depression (see Chapter 15), which is a major problem after a heart attack, and greatly increases the likelihood of dying. Doing yoga makes you feel better about yourself and more hopeful about your ability to get better. The resulting increase in optimism can encourage you to keep up your practice and make other lifestyle changes that contribute to better health.

Yogic Tool: KARMA YOGA. “My experience is that nothing opens the heart, whether it’s a sick heart or a healthy heart, quicker than doing service,” Nischala says. “There is always an opportunity to serve.” See Chapter 16 for an example of how karma yoga can help in heart disease.

New breakthroughs in the understanding of heart disease are causing some doctors and scientists to focus not just on large blockages in major arteries—like the 90 percent occlusion that led to Ron Gross’s angioplasty—but to smaller blockages as well. Dean Ornish explains why. Those large blockages, he says, “aren’t the ones that are likely to kill you,” because new blood vessels called collaterals are likely to have grown around the blockage to supply blood to the area at risk, and also because by the time a blockage has gotten that large, “it tends to be stable, calcified.” Heart attacks are more likely to be caused “by the 20 to 30 percent lesions,” which are “usually fresh…not calcified…and more likely to become unstable.” Given this new understanding, holistic approaches make particular sense. Rather than targeting only the largest blockages, as interventions like angioplasty and bypass surgery do, yoga works in a systemic way and is likely to have effects on blockages large and small.

The Scientific Evidence

In 1948, in what may have been the first reported use of yoga therapy in a Western medical journal, Aaron Friedell, MD, described the use of “attentive breathing” in eleven patients with angina in the journal Minnesota Medicine. Attentive, or mindful, breathing consists of inhaling and exhaling slowly, taking brief pauses between each inhalation and exhalation. Dr. Friedell first learned the technique in 1927 from Paramahansa Yogananda, author of the classic Autobiography of a Yogi. Friedell later refined the technique, teaching his patients alternate nostril breathing, “closing one nostril while inhaling slowly through the other.” The patients, some of whom were debilitated by chest pain and shortness of breath, noted marked improvement of their symptoms. They would begin their mindful breathing as soon as they felt the first signs of an angina attack coming on and could usually make it go away quickly. Some of the patients were able to discontinue all use of nitroglycerin and other medications.

The benefits of yogic breathing were documented again in a Western medical journal fifty years later. A 1998 study, published in The Lancet, found that a yoga technique called “complete breathing”—in which you use the abdominal muscles to exhale as fully as possible, allowing a larger inhalation on the subsequent breath—helped patients with congestive heart failure (CHF) to breathe better (see Chapter 2). After only a month of training, subjects taught this form of yogic breathing were getting more oxygen into their systems and doing it with fewer breaths per minute than controls. They were also able to exercise more.

Dr. Dean Ornish’s studies, published in such leading medical journals as JAMA and The Lancet beginning in 1983, tell us more about the health benefits of a comprehensive program of yoga and lifestyle changes. The yoga portion of the Lifestyle Heart Trial, which was designed by Nischala—a modification of the standard Integral yoga class as taught by her guru Swami Satchidananda—included asana, pranayama, visualization, meditation, and deep relaxation. The rest of the program consisted of a low-fat vegetarian diet, smoking cessation, group support sessions, and aerobic exercise. Following the weeklong intensive training, patients attended regular meetings in their communities and were asked to continue the diet, yoga, and exercise on their own. One year after starting the program, LDL cholesterol levels dropped from an average of 144 to 87 in people who were not taking medication to lower their levels. Patients who followed Ornish’s program had 91 percent reduction in the frequency of their angina, as well as a significant reduction in severity of attacks.

What was most striking about the Lifestyle Heart Trial is that the patients who did the program showed reversal of their heart disease. That is, when they came in for retesting after five years of following the precepts of the program, their blockages had gotten smaller and positron emission (PET) scans showed that the heart muscle was receiving an increased supply of oxygen-carrying blood. When I was in medical school in the 1980s, such a reversal was considered impossible. Everyone “knew” that blockages only got bigger over time, which is precisely what happened to patients in Ornish’s control group who followed standard medical care. Subjects in the Ornish program improved quickly, and—even better—their heart disease continued to reverse during the third and fourth years of the program. Though many in the control group were taking medication to lower cholesterol, their disease nonetheless continued to progress. Many in the yoga and lifestyle program were able to get off blood-pressure medication, too, in part because of the average weight loss in the first year of almost twenty-four pounds.

While the Lifestyle Heart Trial involved 48 patients (28 who did the program and 20 controls), the research was later extended to eight medical centers around the country and a total of 440 patients, with similarly impressive improvements in risk factors such as blood pressure, cholesterol levels, and body weight. The authors wrote that the program “may be particularly beneficial for women,” given their excellent results and a prognosis generally worse than men’s after heart attacks, bypass surgery, and angioplasties. Both men and women were able to avoid bypass surgery for three years without any increase in illness or death due to heart disease. More recently, as part of an effort to gain Medicare coverage for the program, Dean Ornish is compiling data on over 2000 patients like Ron who have taken the week-long training. These data are still being collected and analyzed, but the results so far are very persuasive: Within twelve weeks of beginning the program, patients achieve significant reductions in cholesterol and other blood fats, C-reactive protein, fasting blood sugars, hemoglobin A1c (a measure of long-term control of blood sugar), and systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and these changes are sustained after a year. Patients also enjoy statistically significant improvements in quality of life and measures of depression and hostility.

While it’s impossible to say for sure how big a role yoga played in the program’s success, those involved in the research view it as crucial. Yoga reduced stress and stress-related behaviors like smoking and dietary excess, Dean says, and made it easier for people to adhere to the program’s other elements. In Nischala’s opinion, yoga “seemed to be the catalyst for making everything else happen.” Whatever the reason, she says that people who practiced yoga at home tended to get quicker relief of angina and other symptoms, as well as greater reversal of the buildup of the plaque in their arteries.

Numerous studies from India have also documented the ability of a comprehensive yoga program to improve heart disease and its risk factors. A controlled trial conducted at the Yoga Institute in Santacruz near Mumbai examined the effects of a comprehensive yogic intervention on 113 patients with angiographically proven coronary artery disease. The yoga program included instruction on yogic techniques, lifestyle recommendations, and a low-fat diet rich in fiber, vitamins, and antioxidants. The controls received standard medical care, and both groups continued prescribed medication. At the end of one year, the yoga group had a 23 percent drop in cholesterol (247 to 185) compared to 4 percent among controls, and a 26 percent reduction in LDL cholesterol (146 to 108) compared to 3 percent in the control group. On repeat angiography after one year, 70 percent of the yoga group had smaller blockages versus 28 percent of controls, while 10 percent of the yoga group had larger blockages versus 36 percent of controls. In addition, the researchers found that even patients who had only a small improvement on their angiograms noted a major reduction in symptoms, likely a reflection of yoga’s systemic benefits. A randomized controlled trial of 93 patients conducted by Dr. A. S. Mahajan and colleagues at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences in New Delhi found a yoga program resulted in statistically significant weight loss as well as improvements in total, LDL, and HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides. Two other Indian studies had similar findings.

Nischala Devi’s Approach

Nischala is a big believer in the “less is more” philosophy. “Most people I see—and not just the people who have heart disease—push beyond their limit.” If you have any questions about your ability to do any of the practices described below, please do less than you think you can (especially if you’ve got type A traits). Any of the sitting practices can be done in a chair if that’s more comfortable.

Nischala incorporates a Deep Relaxation pose at several stages of her therapeutic practice, not just at the end of the practice as is common. She understands that relaxation is not necessarily something that many heart patients like. Indeed, many want to skip it, feeling it’s a waste of time. In Nischala’s experience, however, it’s a critical part of the practice, and the more you do it, the better relaxation feels. She has found it can be useful for lowering heart rate and relieving anginal pain, and cardiologists have told her that when patients engage in deep relaxation during an angiogram, there is a visible release of spasm in the coronary arteries.

If you have intermittent angina and the pattern is stable—it comes on with a certain level of exertion, subsides with rest, and does not seem to be getting worse—it’s okay to do yoga as tolerated and back off if symptoms appear. However, angina that is new or more pronounced than usual should prompt an immediate medical evaluation as it may herald an impending heart attack.

If you have intermittent angina and the pattern is stable—it comes on with a certain level of exertion, subsides with rest, and does not seem to be getting worse—it’s okay to do yoga as tolerated and back off if symptoms appear. However, angina that is new or more pronounced than usual should prompt an immediate medical evaluation as it may herald an impending heart attack.

Here is the sequence of practices and instructions that Nischala provided for Ron, the same one used in the Lifestyle Heart Trial, and found on her audio recording Relax, Move & Heal, which Ron used to guide his home practice.

EXERCISE #1. NECK MOVEMENTS. Sit in a comfortable position with your back straight but not rigid. Close your eyes. Bring your awareness to the breath, and observe it as it flows in and out, gently and through your nose. Now you are ready to begin the neck movements:

1. Inhale and bend your head forward so that the chin comes toward the chest. As you exhale, allow all the muscles in the back of the neck to relax (figure 19.1a). Inhale and lift your head back up. Exhale and relax.

2. Inhale and bring your right ear toward the right shoulder. Exhale, and feel the stretch on the left side of the neck, making sure you aren’t lifting the shoulder to the ear (figure 19.1b). Inhale and bring your head back to center. Exhale and relax. Repeat this stretch on the other side.

EXERCISE #2. SHOULDER MOVEMENTS. Sit in a comfortable position with your arms loose at your sides. Practice the following shoulder movements:

1. Inhale and bring your shoulders forward, as if to make them touch in front of your chest, which moves your shoulder blades apart (figure 19.2a). Exhale and relax your shoulders.

2. Inhale and lift your shoulders toward the ears (figure 19.2b). Exhale and release.

3. Inhale and bring your shoulders back, moving your shoulder blades close together, toward your spine (figure 19.2c). Feel your chest expand. Exhale and relax. Gently shake your arms.

Now combine all three movements in the following order:

1. Inhale and raise your shoulders up toward the ears.

2. Exhale and move your shoulders forward and toward each other.

3. Inhale and bring your shoulders down.

4. Exhale and bring your shoulders back, moving the shoulder blades together.

Repeat steps 1 through 4 for several cycles, then do several cycles of the same movements, but moving in the opposite direction. When you’re done, notice any relaxation that’s come in your arms and shoulders, and gently shake out your arms.

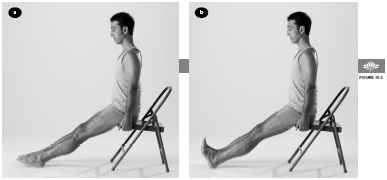

EXERCISE #3. ANKLE MOVEMENTS. Sit on the floor with your legs stretched out in front of you. Practice the following ankle movements:

1. Exhale and point your toes away from you (figure 19.3a). Inhale and lift your toes toward you (figure 19.3b). Repeat twice more.

2. Move your toes in a clockwise direction, keeping your legs still so the movement comes from your ankles, not your legs (figures 19.4a & b). Begin slowly at first, then increase the size of the circle and the speed. Do three repetitions. Repeat in the opposite direction.

EXERCISE #4. KNEE TO CHEST POSE. Sit with your legs stretched out in front of you. Bend your right knee, leaving the sole of the left foot on the floor. Inhale, and use your hands to bring your right thigh up toward your chest. Exhale, lower your head slightly, and give the leg a good hug (figure 19.5). Inhale, and raise the head. Exhale, and release your arms, allowing the leg to return to the floor. Give your legs a gentle shake. Relax. Repeat on the other side.

EXERCISE #5. RELAXATION POSE (Savasana)/Body Scan, one minute. Start by lying on your back with a pillow under your head and another behind your knees. Allow your arms and legs to relax by your sides. Turn your palms up, if that’s comfortable. Close your eyes, and breathe slowly and deeply (figure 19.6). When you are settled, begin to mentally observe and release any tension in your body. Start with your feet, lower legs, thighs, and hips. Relax. Next move to your hands, arms, shoulders, abdomen, chest, and throat. Relax. Then move to your back and spine, neck, head, and face. Relax. If you detect any strain or tiredness, use the breath to help release it. On the inhalation, imagine a fresh supply of energy entering each part of your body. On the exhalation, imagine any tiredness or tension being released. Allow your body to relax completely.

EXERCISE #6. COBRA POSE (Bhujangasana). Start by lying on your belly with your feet parallel and your heels together. Place your palms flat on the floor beneath your shoulders, with your elbows close to your body and your fingers pointing forward. Extend your chin. Inhale, and slowly lift up your head and neck. Lift the upper chest slightly off the floor (figure 19.7). (Do not push the hands into the floor, as this can raise your blood pressure.) Stay for a few relaxed breaths, and then lower back down, touching your chin down before the forehead. Rest for a moment, with your cheek turned to one side and your arms at your sides. Stretch only as far as is comfortable. Each time you may have a different capacity.

EXERCISE #7. HALF LOCUST POSE (Salabhasana), ten seconds. Start by lying on your belly, facedown with your chin on the floor. Place your arms alongside your body or tuck your arms under your body, if it’s comfortable. Keeping your right leg straight, inhale and raise the leg a few inches off the floor (figure 19.8). Holding steady, breathe normally. Then slowly lower your leg and allow it to relax. Repeat with the left leg.

EXERCISE #8. RELAXATION POSE (Savasana), one minute. Return to the relaxation position described above. Tune in to your body. Notice any discomfort, trembling, muscle aches, or disturbed breathing that might have resulted from the backbends (Cobra and Half Locust). Nischala says, “Be aware of the internal signals. Learn the difference between a good stretch and something that is doing harm.”

EXERCISE #9. SEATED FORWARD BEND (Paschimottanasana). Start by sitting on the floor with your legs stretched out in front of you, and the knees slightly bent. Place one pillow under your hips and a second behind your knees. Lock your thumbs together and raise your arms up toward the ceiling. Inhale and stretch your arms and torso as you look up. Then exhale and bend forward over your legs. Stopping halfway, inhale and stretch toward the wall in front of you. Then exhale and release forward over your outstretched legs. Hold on to your legs wherever it’s comfortable, and relax (figure 19.9). If there is any pain in your legs or back, do not come so far forward. After several breaths, lock your thumbs again, inhale, and stretch your arms as you come up.

EXERCISE #10. RELAXATION POSE (Savasana), one minute. Return to the relaxation position described above.

EXERCISE #11. SUPPORTED SHOULDERSTAND (Salamba Sarvangasana), modified. Lie on your back near a wall, with your knees bent and your buttocks as close to the wall as possible. Turn your palms down and press them into the floor. Bring the soles of your feet to the wall, and begin to walk up the wall (figure 19.10a). As you do this, bring your hands to your lower back for support. Breathe normally and go up only as high as is comfortable, without any strain. If you’re comfortable doing so, straighten your legs, allowing them to lean against the wall (figure 19.10b). If you develop dizziness or feel pressure in your head or neck, come out of the pose right away. Otherwise, stay up for one minute or less, and gradually build up your time in this pose to three minutes. Come out of the pose slowly by walking your feet down the wall and lowering your buttocks to the floor.

EXERCISE #12. RELAXATION POSE (Savasana), thirty seconds. Lie down in the relaxation position described above.

EXERCISE #13. FISH POSE (Matsyasana), modified, thirty to sixty seconds. Start by lying on your back. Bring your legs together and use your hands to grasp the sides of each thigh. Using your elbows for support, come to a half-seated position. Lean back and slowly tilt your head backward as far as you comfortably can and place your head on the floor. Balance your weight between the head, elbows, buttocks, and legs. If this is not comfortable for you, place a pillow under your shoulders and allow your head to tilt over the edge of the pillow (figure 19.11). The chest and heart center are fully expanded, so breathe through your nose, deeply and easily. Relax your shoulders. To come out of the pose, reverse the tilt of your head, and slowly lower your back, neck, and head down to the floor.

EXERCISE #14. DEEP RELAXATION POSE (Savasana), one minute or longer. Return to the relaxation position described above.

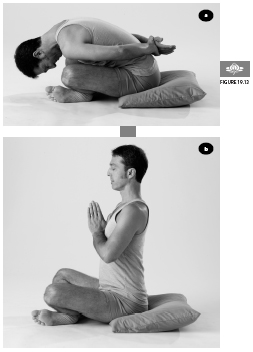

EXERCISE #15. HALF SPINAL TWIST (Ardha Matsyendrasana), thirty seconds. Sit on a pillow on the floor with your legs stretched out in front of you, with a slight bend in the knees. Place your left foot outside of your right leg, between the knee and ankle, and place your left arm on the floor behind you. Press your right arm against your left leg, and reach toward and grasp your right knee. If you can’t reach your knee, place your right hand on your left hip. Inhale and twist around to the left (figure 19.12). Exhale and relax into the pose, keeping your breath normal and easy. To come out of the pose, inhale and return to your starting position. Gently shake out your legs and repeat the pose on the other side.

EXERCISE #16. YOGIC SEAL POSE (Yoga Mudra), thirty to sixty seconds. Sit in a comfortable cross-legged position with your eyes closed. Bring your arms behind your back and take hold of your right wrist. Inhale and stretch your arms up. Exhale, extend your chin, and fold your body forward over your legs. When you have come forward as much as you comfortably can, allow your body and head to relax (figure 19.13a). To come out of the pose, inhale, extend your chin, and slowly raise your head and body back to a seated position. As you exhale, bring your palms together at the chest (figure 19.13b), and feel the effects of the yogic seal.

EXERCISE #17. RELAXATION POSE (Savasana)/Guided Imagery. Return to the supine relaxation position described above. When you are settled, observe your body from bottom to top, part by part. Anywhere you notice tension, imagine your breath going there and inducing relaxation. Slowly bring your awareness to the gentle breath as it enters and leaves the body. As it enters, it brings with it oxygen and healing energy. As it leaves, feel yourself letting go of that which you no longer need. Imagine that your entire body is beginning to fill with healing energy, and slowly allow that energy to grow. Gradually begin to deepen the inhalation, and as you do, feel fresh vital energy enter through the top of your head, coming down your face and neck, into the spine and back to the abdomen, into the heart, and down the arms to the hands, the legs to the feet. The whole body fills with fresh, vital, healing energy.

Take care with the pranayama practices that follow. Nischala says, “The breath is always steady and gentle without any strain. If at any time you feel dizzy or light-headed, please discontinue the practice, and allow the breath to return to normal.”

Take care with the pranayama practices that follow. Nischala says, “The breath is always steady and gentle without any strain. If at any time you feel dizzy or light-headed, please discontinue the practice, and allow the breath to return to normal.”

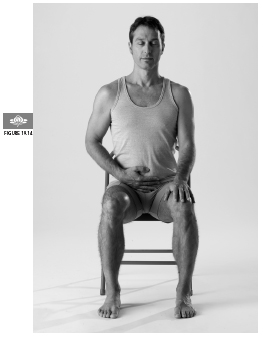

EXERCISE #18. THREE-PART BREATHING (Dheerga Svasam), three minutes. Sit on a chair in a comfortable upright position with your eyes closed. Place your right hand on your abdomen, with your thumb resting on your navel and your fingers embracing your belly (figure 19.14).

1. First part: When you are settled, exhale completely through your nose. At the end of the exhalation, gently pull in your abdomen. Begin the inhalation by releasing your abdomen and allowing the lower lungs to fill. Then pull in your abdomen as you exhale. Inhale, expand the abdomen. Exhale, contract the abdomen. Practice this first part of the three-part breath until you feel comfortable with it.

2. Second part: Inhale, expanding the abdomen and then fill the lower ribs. On the exhalation, reverse the order, exhaling from the lower ribs and then the abdomen. Practice the two-part breath until you feel comfortable with it.

3. Third part: After filling the abdomen and lower ribs, inhale into the upper chest, and feel your collarbones rise slightly. On the exhalation, contract the upper chest, the lower chest, and the abdomen, one section following the other. Continue breathing in this manner slowly and deeply.

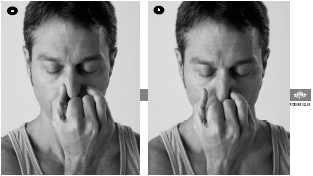

EXERCISE #19. ALTERNATE NOSTRIL BREATHING (Nadi Shuddhi), five rounds. (In many other styles of yoga, this practice is called Nadi Shodhana.) Take the same seated position as in exercise #16. Make a gentle fist with your right hand and then release the thumb and the last two fingers. Inhale and then gently close off the right nostril with the thumb (figure 19.15a). Exhale slowly through the left nostril. Inhale deeply through the left nostril, and then gently close off the left nostril with the last two fingers (figure 19.15b). Exhale through the right, inhale through the right and close the right nostril with the thumb. (If holding your hands in this fashion is awkward or uncomfortable, Nischala recommends using any hand position you like to close off the nostrils.) This constitutes one cycle. Repeat one or more times, breathing slowly and deeply. Notice how calm and still the breath and the mind have become, and observe the connection between the two.

EXERCISE #20. MEDITATION, one or more minutes. Sitting in your chair or on a pillow, take a comfortable seated position and close your eyes. During the silence, focus the mind on one thing. You may use the breath as you did in Deep Relaxation or just focus on the peace and stillness within. Please check your posture and keep your body still during this entire time. As your body becomes still and quiet, the mind follows. Stay for a minute or longer, building up gradually over time.

Contraindications, Special Considerations, and Modifications

Nischala’s program is gentle enough that the risk to heart patients is low. She thinks that more vigorous practices can sometimes be appropriate as long as you build up slowly over time, ideally under the supervision of a skilled teacher. If you have been sedentary, suddenly doing ten Sun Salutations in a row may not be any better an idea than going for a five-mile run. A cardiac-stress test or other tests to evaluate your risk may be appropriate for anyone over fifty (or even younger if you have a number of cardiac risk factors) who plans to begin a vigorous yoga practice.

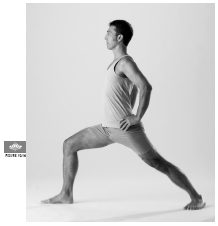

Other practices that could be too much for heart patients include arm balances, full backbends, and even some of the standing poses, particularly if they are held for a long time or, Nischala says, if done with locked knees (for more on locking the knee, see appendix 1, “Avoiding Common Yoga Injuries”). She says that people with heart disease should “never, ever hold their breath.” Vigorous breathing practices like Kapalabhati and Bhastrika are also contraindicated. B. K. S. Iyengar advises against unsupported inversions in people with heart disease because he believes that the weight of the abdominal organs puts a strain on the heart. (The modified Shoulderstand Nischala teaches is fine.) He also suggests foregoing long holds of Downward-Facing Dog. Iyengar recommends that heart patients do standing poses like Warrior I with the hands on the hips rather than overhead, to lessen the burden on the heart (figure 19.16). As always, it’s not just the poses that are potentially a problem but how you do them. Straining or pushing yourself, even in easier poses, invites problems.

For heart patients who have shortness of breath—due to congestive heart failure, for example—Nischala suggests that Deep Relaxation be done with pillows under the upper back and head, aligned in a T shape, and under the knees (figure 19.17a). If you are unable to lie on your back, she suggests the pose be done lying on your right side, with pillows placed under the head, between the arms, and between the knees, which are bent (figure 19.17b). For more marked shortness of breath, she will either prop students up on a number of pillows leaning against a wall or, in even more severe cases, in a chair against a wall.

OTHER YOGIC IDEAS

Restorative chest openers like Bridge pose (Setu Bandha), Reclined Cobbler’s pose (Supta Baddha Konasana), and Supported Relaxation pose (Savasana) (see Chapter 3) are commonly recommended in Iyengar yoga for the treatment of heart disease. These poses are relaxing, expand the chest, and allow deep breaths to bring oxygen into the system. Although their claims have not been evaluated scientifically, Iyengar yogis believe these poses help the development of collateral blood vessels.

A Holistic Approach to Heart Disease

Fruits and vegetables are a rich source of healthy phytochemicals, such as bioflavonoids and other antioxidants, which fight heart disease. Bioflavonoids in grapes, grape juice, and wine, especially red wine, as well as in plums, cherries, and blueberries, can help prevent LDL (bad) cholesterol from oxidizing and becoming more dangerous. Antioxidant supplements do not appear to work as well (see Chapter 4).

Fruits and vegetables are a rich source of healthy phytochemicals, such as bioflavonoids and other antioxidants, which fight heart disease. Bioflavonoids in grapes, grape juice, and wine, especially red wine, as well as in plums, cherries, and blueberries, can help prevent LDL (bad) cholesterol from oxidizing and becoming more dangerous. Antioxidant supplements do not appear to work as well (see Chapter 4).

While low-fat diets can lower cholesterol readings, there is growing evidence that some fats—like the monounsaturated fats in olive oil and the omega-3 fatty acids found in flaxseeds and such fish as salmon, herring, and sardines—are good for the heart. Omega-3 fatty acids fight inflammation and appear to lower the risk for arrhythmias, potentially fatal abnormal rhythms that underlie many cases of sudden death. They also can lower triglyceride levels.

While low-fat diets can lower cholesterol readings, there is growing evidence that some fats—like the monounsaturated fats in olive oil and the omega-3 fatty acids found in flaxseeds and such fish as salmon, herring, and sardines—are good for the heart. Omega-3 fatty acids fight inflammation and appear to lower the risk for arrhythmias, potentially fatal abnormal rhythms that underlie many cases of sudden death. They also can lower triglyceride levels.

Nuts and avocados contain heart-healthy fats (though you shouldn’t overindulge since they are calorie-rich). Healthy nuts include almonds, pecans, and walnuts.

Nuts and avocados contain heart-healthy fats (though you shouldn’t overindulge since they are calorie-rich). Healthy nuts include almonds, pecans, and walnuts.

While the saturated fats in full-fat dairy products and meats can up your risk, it seems that the “trans” fats—found in some margarines, fried foods, and anything that lists “partially hydrogenated” fat on the label—are even worse.

While the saturated fats in full-fat dairy products and meats can up your risk, it seems that the “trans” fats—found in some margarines, fried foods, and anything that lists “partially hydrogenated” fat on the label—are even worse.

Taking low-dose or children’s aspirin to thin the blood may lower the risk of a heart attack. Since it’s not appropriate for everyone, be sure to talk to your doctor first.

Taking low-dose or children’s aspirin to thin the blood may lower the risk of a heart attack. Since it’s not appropriate for everyone, be sure to talk to your doctor first.

People with heart disease appear to benefit from getting a flu shot each fall.

People with heart disease appear to benefit from getting a flu shot each fall.

B vitamins, usually included in a multivitamin, may lower the risk for heart disease by dropping the level of a protein called homocysteine, which in recent years has been recognized as an independent risk factor for heart attack.

B vitamins, usually included in a multivitamin, may lower the risk for heart disease by dropping the level of a protein called homocysteine, which in recent years has been recognized as an independent risk factor for heart attack.

The B vitamin niacin, in higher doses, can effectively (and inexpensively) lower LDL (bad) cholesterol and triglyceride levels and boost levels of the HDL (good) cholesterol. Facial flushing, a common side effect, can be diminished by increasing the dose slowly, taking it before bed, and using time-released preparations. Be sure to discuss with your doctor, who will want to check liver function regularly.

The B vitamin niacin, in higher doses, can effectively (and inexpensively) lower LDL (bad) cholesterol and triglyceride levels and boost levels of the HDL (good) cholesterol. Facial flushing, a common side effect, can be diminished by increasing the dose slowly, taking it before bed, and using time-released preparations. Be sure to discuss with your doctor, who will want to check liver function regularly.

Coenzyme Q10, an antioxidant and natural constituent of human cells, may improve endothelial function (the endothelium is the lining of blood vessels and is crucial in preventing plaque buildup and blood clots). Since some evidence suggests that statins like Lipitor (atorvastatin), Zocor (simvastatin), and Mevacor (lovastatin) lower CoQ10 levels, it may be a particularly good idea for anyone taking these cholesterol-lowering drugs to take CoQ10 as a supplement.

Coenzyme Q10, an antioxidant and natural constituent of human cells, may improve endothelial function (the endothelium is the lining of blood vessels and is crucial in preventing plaque buildup and blood clots). Since some evidence suggests that statins like Lipitor (atorvastatin), Zocor (simvastatin), and Mevacor (lovastatin) lower CoQ10 levels, it may be a particularly good idea for anyone taking these cholesterol-lowering drugs to take CoQ10 as a supplement.

Not sleeping enough increases the risk of a heart attack (see Chapter 23).

Not sleeping enough increases the risk of a heart attack (see Chapter 23).

Drinking plenty of fluids throughout the course of the day appears to lower the risk of heart attack, presumably by preventing the increase in clotting that happens with dehydration.

Drinking plenty of fluids throughout the course of the day appears to lower the risk of heart attack, presumably by preventing the increase in clotting that happens with dehydration.

Fight inflammation of your gums not just by flossing, brushing, and getting regular dental cleanings, but by scraping your tongue daily with a plastic or metal tongue scraper that is available in pharmacies and health food stores.

Fight inflammation of your gums not just by flossing, brushing, and getting regular dental cleanings, but by scraping your tongue daily with a plastic or metal tongue scraper that is available in pharmacies and health food stores.

When Ron began the week-long Ornish program six years ago he was having a lot of angina. He might go through five or six nitroglycerin tablets just warming up to play tennis. After he completed the week-long program, “I didn’t feel any big difference physically,” he says, “but I did feel a lot more relaxed psychologically. When the program was over, I got one of Nischala’s tapes [Relax, Move & Heal], and continued the low-fat vegetarian diet.” He also began to attend monthly group meetings, which program participants are encouraged to attend.

Once he established a home practice to Nischala’s tape every morning, Ron started to notice a huge difference. Nischala says, “Within a few days he couldn’t believe how good he felt.” Two months after doing the week-long program, his anginal episodes had become so infrequent that he put off having the second angioplasty that had been suggested by his doctors, and he still hasn’t needed it.

Although he followed the program’s dietary guidelines strictly at first, Ron came to believe that the 10 percent limit on dietary fat was too low in fat for him. “My skin started to dry out; it was peeling all over my face. I needed a little more oil than that.” On a trip to rural Japan where food choices were limited, he ended up adding fish, which turned out to be better not only for his skin but for his cholesterol. “My total cholesterol dropped down to 150, which is a very good number.” His triglyceride level dropped, too. On the modified diet, however, Ron has gained back most of the fifteen pounds he lost when he started the program.

When he began his home practice, Ron listened to only the first thirty minutes of Nischala’s recording (through exercise #16, Yogic Seal pose). Only after three years of doing that was he able to make it through the imagery, meditation, and breathing exercises on the second side of the tape, too. He now does the entire practice every day. Being a typical type A, Ron cautions that most people would find it easier to start with the physical work and only gradually move into the relaxation and breathing work—though he has concluded that the relaxation and breathing have actually been more important to him from a psychological standpoint.

Beyond just improving his heart condition, Ron seems to have developed some of the equanimity that yogis claim is a benefit of the practice. If traffic is tied up on his way to work, it doesn’t bother him the way it used to. Now, he says, “If I start to get a little anxious, sitting there in traffic and not moving, I take a couple of real deep breaths and I can reach the point where I can literally relax the muscles in my body.” The effects have spilled over into his business as well. “I don’t get tight stomach muscle pains because things aren’t going my way” in tough negotiations. “If the guy is really hard-nosed, so what? Good luck.”

Yoga, he says, “definitely changed my whole personality, my whole character. I stepped off the treadmill.” Nonetheless, the essence of the old Ron remains. “I still go to work, and I haven’t gotten rid of my type A personality completely. I’m seventy-six and I decided to go back to college.” He’s studying oceanography and can’t keep himself from cramming for the exams to make sure he gets a good grade. Ron has also taken up tap dancing in the last few years, and now gives regular performances. He’s still a pitta but he’s become a much more sattvic (balanced) one.