CHAPTER 24

IRRITABLE BOWEL SYNDROME

Thirty years ago, MICHAEL LEE was working for the South Australian Public Service Board, studying how people behaved in the workplace and running workshops on how to effect change. He gradually came to realize that the behavioral principles that were the basis of his workshops were insufficient. “I felt the piece that was missing was the body,” an insight he thinks had been awakened by starting a yoga practice. “When I first began to practice yoga, I realized that there was a real connection between what was going on in my body and in my life.” One day his young daughter said to him, “Daddy, I like when you do your yoga. When you do your yoga you don’t get so mad at me.” That was a powerful confirmation. In 1984, he took a sabbatical from the work he was doing for the government of Australia and went to the Kripalu Center for Yoga and Health in Lenox, Massachusetts, for the express purpose of developing new programs. Michael admits that the Australian government never got their money back on that investment. “I got so into yoga that I went back and resigned.” He developed Phoenix Rising Yoga Therapy in 1986 and ran their center and teaching programs until 2006, when he stepped down to pursue writing and other interests. Michael has written two books: Turn Stress Into Bliss and Phoenix Rising Yoga Therapy. He has two master’s degrees, one in behavioral psychology, the other in holistic health education.

Thirty years ago, MICHAEL LEE was working for the South Australian Public Service Board, studying how people behaved in the workplace and running workshops on how to effect change. He gradually came to realize that the behavioral principles that were the basis of his workshops were insufficient. “I felt the piece that was missing was the body,” an insight he thinks had been awakened by starting a yoga practice. “When I first began to practice yoga, I realized that there was a real connection between what was going on in my body and in my life.” One day his young daughter said to him, “Daddy, I like when you do your yoga. When you do your yoga you don’t get so mad at me.” That was a powerful confirmation. In 1984, he took a sabbatical from the work he was doing for the government of Australia and went to the Kripalu Center for Yoga and Health in Lenox, Massachusetts, for the express purpose of developing new programs. Michael admits that the Australian government never got their money back on that investment. “I got so into yoga that I went back and resigned.” He developed Phoenix Rising Yoga Therapy in 1986 and ran their center and teaching programs until 2006, when he stepped down to pursue writing and other interests. Michael has written two books: Turn Stress Into Bliss and Phoenix Rising Yoga Therapy. He has two master’s degrees, one in behavioral psychology, the other in holistic health education.

Michael Faber started to develop digestive problems after returning from a trip to South America. His major symptoms early on were constipation and gas. In search of a diagnosis, he went to several doctors, none of whom were able to figure out what the problem was. Finally, after three or four years, he was given the diagnosis of intestinal parasites and treated with antibiotics that got rid of the infection. Even so, some digestive symptoms persisted.

During a stint as a volunteer in the kitchen at the Kripalu Center for Yoga and Health, at a time when he was still having digestive problems (mainly diarrhea and some abdominal discomfort, as well as gas and bloating), he began to be aware that he was living with a lot of anxiety.

As he gained more awareness of his mental state, he was able to correlate it with his symptoms—or lack thereof. For example, on backpacking and camping trips when he was able to relax, “I realized that some of these symptoms that I experienced almost disappeared.” When he could see that there was a psychological component to his digestive issues, he saw a therapist, who suggested he try meditation. Around that time, he saw a flyer for Michael Lee’s eight-week program using Phoenix Rising yoga and mindfulness meditation to help irritable bowel syndrome. He decided to give it a try.

Overview of Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), formerly known as spastic colon (among other names), is an intestinal problem of unknown cause, though stress appears to be a prominent factor. Its symptoms often include diarrhea, constipation, or both, as well as bloating and cramping. Uncoordinated intestinal contractions, in which one area contracts, attempting to push the food being digested forward, before the area below it is ready, help account for the crampy abdominal pain reported by IBS sufferers. Typically the pain will be relieved by a bowel movement—a pattern that is one of the markers of IBS. Symptoms range from mild to severe and can be intermittent—manifesting, for example, only at times of heightened stress—or nearly constant.

In IBS there is no blood in the stool, no fever, chills, or weight loss. The presence of any of these should prompt a trip to the doctor to look for another cause.

In IBS there is no blood in the stool, no fever, chills, or weight loss. The presence of any of these should prompt a trip to the doctor to look for another cause.

While bothersome and at times painful, IBS does not cause permanent damage to the body and does not increase the risk of developing cancer later on. Some people believe that a prior intestinal infection, such as Michael had with parasites, may predispose you to developing IBS, but scientists have come to no definite conclusions on this score. Those with IBS appear to be more sensitive to sensations in their bowels. The same degree of bowel distention or bloating, for example, causes more discomfort in someone with the syndrome than someone who doesn’t have it.

Such problems as lactose intolerance (sensitivity to the natural sugar found in milk) or gluten sensitivity can cause diarrhea and bloating. If you notice such digestive symptoms after eating dairy products or high-gluten foods like bread and pasta, be sure to consult your doctor. Another source of unexplained gastrointestinal symptoms, sometimes leading to a mistaken diagnosis of IBS, is fructose intolerance. Like lactose, fructose is a naturally occurring sugar (found in fruit and in high-fructose corn syrup, a low-cost sweetener used in soft drinks and a wide variety of processed foods) that can cause digestive problems in people who don’t absorb it normally. A study, published in the American Journal of Gastroenterology, found that 134 out of 183 patients with unexplained intestinal symptoms had a positive breath test for fructose intolerance. Commonly reported symptoms included flatulence (83 percent), pain (80 percent), bloating (78 percent), belching (70 percent), and altered bowel habits including diarrhea (65 percent). If you suspect you might have fructose intolerance, ask your doctor about scheduling a breath test.

Such problems as lactose intolerance (sensitivity to the natural sugar found in milk) or gluten sensitivity can cause diarrhea and bloating. If you notice such digestive symptoms after eating dairy products or high-gluten foods like bread and pasta, be sure to consult your doctor. Another source of unexplained gastrointestinal symptoms, sometimes leading to a mistaken diagnosis of IBS, is fructose intolerance. Like lactose, fructose is a naturally occurring sugar (found in fruit and in high-fructose corn syrup, a low-cost sweetener used in soft drinks and a wide variety of processed foods) that can cause digestive problems in people who don’t absorb it normally. A study, published in the American Journal of Gastroenterology, found that 134 out of 183 patients with unexplained intestinal symptoms had a positive breath test for fructose intolerance. Commonly reported symptoms included flatulence (83 percent), pain (80 percent), bloating (78 percent), belching (70 percent), and altered bowel habits including diarrhea (65 percent). If you suspect you might have fructose intolerance, ask your doctor about scheduling a breath test.

How Yoga Fits In

The smooth functioning of digestion depends on the action of the autonomic (involuntary) nervous system, especially the parasympathetic branch, associated with relaxation and restoration (see Chapter 3). Stress activates the sympathetic side, the fight-or-flight system, which can interfere with the bowels.

Exercise is known to lower stress levels. Beyond this general effect of physical activity, specific yoga postures can offer help with a wide variety of IBS symptoms. For example, people with constipation often benefit from gentle yoga stretches and twists, and, if they are able, more vigorous poses like Sun Salutations and inversions. Since stress can lead to both constipation and diarrhea (as well as cramps, bloating, and other symptoms commonly seen in IBS), a variety of practices, from asana to breathing exercises designed to calm down the sympathetic nervous system and shift the balance more toward the restorative parasympathetic side of the equation, can facilitate better bowel function.

Meditation can help, too. Even in situations where “you can’t change the stress,” Michael Lee says, “you can change your relationship with it. That’s fundamentally where the shift needs to take place.” Yogis believe that meditation may be particularly valuable in this regard because it teaches you to separate your symptoms from your thoughts and worries about them. For someone like Michael Faber, letting go of the worry that so often attaches to symptoms can be transformative.

Self-study (svadhyaya) is also part of the yogic prescription for IBS. Self-study can help you figure out what your stressors are and whether there is a connection between them and your symptoms. Self-study also entails looking at the link between the foods you eat and how they make you feel. If you know that certain foods don’t agree with you but you choose to eat them anyway, yoga would suggest you look further to ascertain why that might be. Keeping a journal in which you write down your symptoms and any possible connection between them and stress, diet, or other factors can facilitate this process of self-discovery.

Another area to study is how you eat. Eating rapidly can lead to swallowing air, which worsens gas and bloating. Taking the time to chew your food thoroughly aids digestion by allowing enzymes in your saliva to mix with food before it gets to your stomach. Bringing more yogic awareness to the entire process of eating can facilitate relaxation by making it more of a meditation (see Chapter 27). Be advised, however, that eating quickly may be a deep samskara (behavioral groove), and you may need to repeatedly bring your attention to it before it changes (see Chapters 1 and 7).

Yoga also looks at possible psychological contributors to conditions like IBS. Michael Lee says that you need to ask yourself “What are the life issues involved? We can give you all sorts of yoga postures, breathing techniques, and herbs to take but if you don’t fundamentally change what’s causing the stress, you can’t effect healing in a complete sense.” He believes that if you walk the path of yoga, you almost inevitably choose to make changes that are life-enhancing. Once you start to experience the calm and peacefulness that lies at your center, it becomes so much easier to treat yourself better by eating healthier, making time for relaxation, and honoring the messages that come from within about what’s good for you and what isn’t.

The Scientific Evidence

A small randomized controlled study conducted at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences in Delhi compared yoga asana and pranayama to treatment with the antidiarrheal drug loperamide in twenty-two males with diarrhea-predominant IBS. Both yoga and the drug proved effective in reducing bowel symptoms as well as anxiety levels at the end of the two-month study. The yoga, however, showed additional beneficial effects, shifting the balance of the autonomic nervous system toward the parasympathetic branch and, for this reason, was judged to be more effective than the drug.

The relaxation response, a technique developed by Dr. Herbert Benson based on yogic mantra meditation, was shown to effectively reduce symptoms in a small randomized controlled experiment conducted at the State University of New York at Albany. Thirteen patients completed a six-week training in the relaxation response and were then asked to practice it for fifteen minutes twice a day. At the end of six weeks, the meditation group experienced better relief than the controls, who had been placed on a waiting list for treatment, noting improvement in flatulence and belching. In a follow-up at three months, the meditation group also noted improvements in bloating and diarrhea. When ten of the original thirteen patients were surveyed one year after beginning the program, they noted significant additional reductions in pain and bloating, which the authors found tended to be the most distressing symptoms of IBS.

Another randomized controlled study of one hundred patients with IBS was conducted at Banaras Hindu University. The patients were divided into three groups. One group was given drug treatment, one a yoga program, and one a combination of drugs and yoga. The yoga intervention consisted of asana, pranayama, kriyas (yogic cleansing techniques), and meditation. The drug therapy included antianxiety drugs, medication to reduce intestinal cramps (antispasmodics), and fiber supplements. After an initial two-week training, the thirty-six members of the yoga group and twenty-eight members of the combined group were asked to practice half an hour per day for the next two months. Both drugs and yoga used alone proved effective in significantly reducing abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhea, anxiety, and other symptoms, with yoga generally more effective than medication. The combination of yoga and modern drug therapy was consistently more effective than either modality alone, eliminating essentially all symptoms within six weeks, with the benefits persisting at the conclusion of the study.

There are also studies suggesting that biofeedback, which shares many features with yoga, especially in the area of heightening bodily awareness and increasing control over normally involuntary processes, can be effective in IBS. Other studies have found utility in hypnosis that involves guided imagery, another technique that is used in yoga. Mixed programs that include meditation and cognitive-behavioral therapy also appear to reduce symptoms.

Michael Lee’s Approach

Normally Phoenix Rising Yoga Therapy (PRYT) is done in a one-on-one setting. But when the idea of forming a group for IBS patients came up, Michael felt he could adapt the principles and guide the students through experiences that would give them close to 90 percent of what they would get in one-on-one sessions. He also thought the group might benefit people through camaraderie. So he and Michael Taylor, a medical doctor trained in Jon Kabat-Zinn’s mindfulness-based stress reduction, formed a group with Taylor teaching basic mindfulness meditation techniques and Lee teaching yoga.

Mindfulness meditation, Michael Lee says, involves watching your mind and noticing: “‘There I am worrying again’ or ‘There I am obsessing about my food again.’” As he explains, you watch your thoughts but try not to get caught up in the drama of them. The yoga he taught was about “entering a deeper level of awareness through the body. The body is used as the focus in stretches that are held at the edge: not too much, not too little. The physical sensation is the initial focus, but then you expand your awareness to “being present to the experience in all its aspects.” What yogis call their “edge” is a place where a pose is intense but not painful, what Michael calls “a tolerable degree of discomfort.” He encourages people to find their own edge, not to compare themselves to someone else (see Chapter 5 for more on this topic).

“There’s a learning curve around doing this kind of body-mind work,” Michael says, “first getting comfortable just being present in the physical. Once that’s achieved you can go to other levels. It might be thoughts, it might be feelings, images, sensations.” People almost always end up hitting on “a recurring theme, and it usually has some deep connection to what’s going on in their life at the present time.” As the students go through the exercises, Michael encourages them to explore whatever is arising in their bodies and minds.

Another part of the Phoenix Rising experience is what Michael calls a “facilitated group process.” This is not the same as group therapy. Rather, he says, “It’s an opportunity for people to talk about their experience in the group, where it can be received without judgment and without criticism. It’s part of the process that we use in the one-on-one Phoenix Rising sessions, where at the end of the session people talk about what happened for them. The goal, he says, is acceptance of what is, so the process does not involve the kind of skilled intervention that a psychotherapist offers.

The practice Michael Lee gave to the students varied from week to week. The following practice is what the group did in the second week, and as homework later on, when they were given a CD recorded during the class to practice along with.

All of the exercises should be done with conscious breathing. As Michael explains, “We teach breathing a little differently than a lot of other people. We begin with a long slow inhale followed by an exhalation that’s basically a letting go. We sometimes call it the ‘surrender breath,’ the ‘what-the-heck breath.’ If you hear people who’ve had a sudden fright and it’s all over, they give a sigh of relief. It’s an inner message to the body: ‘Oh I can relax now, it’s okay.’”

EXERCISE #1. BREATHING WITH ARM MOVEMENT, four to six breaths. Start by standing with your feet together or close together and your arms at your sides, breathing comfortably. Inhale and draw your arms up above your head and hold them there (figure 24.1). Then exhale, encouraging a surrender breath, and lower your arms back down. Repeat twice. Then take stock of the experience you’ve just had. Close your eyes, and feel your whole body and the breath coming and going, in and out.

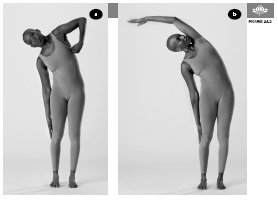

EXERCISE #2. SIDE BENDS, three to four breaths. Start by standing with your hands by your sides. Make a loose fist with your left hand. Slowly inhale and draw your left hand under your left armpit(figure 24.2a), lean to your right side and let your right hand drop toward the knee. From that position, reach up with your left arm and turn your head to lookup at it. Then lengthen your left arm alongside your left ear (figure 24.2b). To come out of the pose, lift your torso and lower your arms. Repeat on the other side.

EXERCISE #3. SWINGING TWIST, sixteen times on each side. Start by standing with your feet hips’ width apart. Swing your arms, and with them your torso, first to one side then the other, pivoting on the foot opposite to the direction in which you are turning, and allowing the heel to lift as you twist (figure 24.3). Keep your whole body long, and let your arms hang loose by your sides like empty coat sleeves. Take deep breaths in and out. Speed up the motion a few times, then slow it down. Inhale, exhale, swing to the left, inhale, exhale, and swing to the right, using the long focused inhalation and the surrender exhalation.

EXERCISE #4. HALF MOON POSE (Ardha Chandrasana), three to four breaths on each side. (Note: this pose differs from the Ardha Chandrasana taught in some other yoga traditions.) From a standing position, raise your arms over your head and make a “steeple” with your fingers by extending your index fingers and interlacing the others. Slowly inhale, and then on an exhalation extend your arms to the side, up and over to the right, lengthening the left side of your body (figure 24.4), slowly finding your edge on that side. Notice whether you try to push the edge, and if you do, just notice that. This is part of a three-part process: awareness, acceptance, and making an adjustment if necessary. Stay for a few more breaths. Then on an inhalation, return to center. Repeat on the other side.

EXERCISE #5. STANDING FORWARD BEND (Uttanasana), with hands in prayer (Namaste) position, three to four breaths. Start by standing with your feet hips’ width apart. Take your hands around behind your back and join your palms together, with your fingers facing up toward your head. Squeeze your shoulder blades together. As you exhale, bend forward from the hips, and as you do, slide your hands up your back. You can separate the palms if you like, and just lace the fingertips together. Allow your head to release downward and bend your knees if you need to. Find the edge in terms of how far your hands go up behind you, so they’re not too far up and not too far down, but just right. Take full, deep breaths. Then as you inhale, slowly roll up out of the pose and then exhale with a sigh.

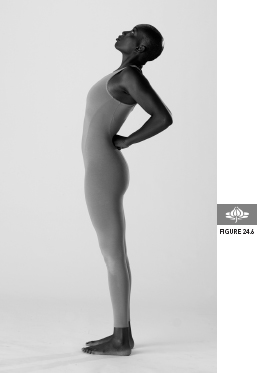

EXERCISE #6. STANDING BACKBEND, three to four breaths. Start by standing with your feet hips’ width apart. Place your fists on either side of your lower back. Then look up at the ceiling, press your pelvis forward, and lean back. See if you can open up your throat and let your head go back to where it feels extended but comfortable. Find an edge there, which might be in either your neck or in your back. If you can’t take a full, deep breath, it’s probably too much, so come up a little and take that full, deep breath. Feel the expansion into your chest and notice the quality of the posture. What’s happening now? Sigh with your exhalation, then inhale as you slowly come back up.

EXERCISE #7. STANDING FORWARD BEND (Uttanasana), three to four breaths. From a standing position, release your arms and your entire body, and bend forward into a rag doll position as you exhale (figure 24.7). Just hang—let your arms and your whole upper body release. You might want to open and close your mouth a few times and roll your jaw around. Let your head be heavy. Bend your legs at the knees a little if you need to. Take slow, deep breaths in and out. To come out of the pose, slowly roll back up to standing as you inhale.

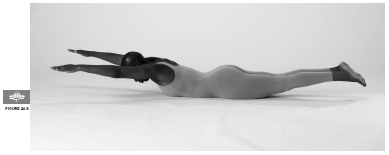

EXERCISE #8. LOCUST POSE (Salabhasana), three to four breaths. Lie flat on your belly with your arms stretched straight in front of your head. Lengthen your body, and then inhale and lift your arms and legs simultaneously off the ground (figure 24.8). Breathe deeply. Staying elevated, lengthen from your left arm to your left leg, then do the same on the right side. Notice whether any struggle is present. If there is, see if you can come to the place of just being with the posture, holding it at the edge but letting go of the struggle. Let the breath hold the posture for you, as you breathe from the belly. Slowly come back down, allowing your body to melt into the floor and turning your head to one side.

EXERCISE #9. COBRA POSE (Bhujangasana), three to four breaths. Lie on your belly with your head facing downward. Place your hands under your shoulders, keeping your elbows tucked into your sides. Press your pelvis toward the floor and slowly lift your head, looking forward. Slowly, take a deep breath in and come up a little bit farther, lifting your chest off the floor. Stay a few breaths, coming up a little higher if you can, but never taking your navel off the floor (see figure 24.9). To come out of the pose, push into your hands as you slowly lower yourself down. Turn your head to one side and relax.

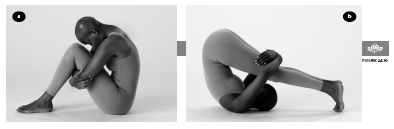

EXERCISE #10. ROCKING AND ROLLING, sixteen repetitions. Start by lying on your back. Bring your knees in toward your chest on an exhalation, and wrap your arms around your legs, drawing them farther toward your chest. Start by gently rocking from side to side, just to give your low back area a little massage on the floor. Let yourself be a little playful. Then begin rocking forward and back, exhaling as you come forward, inhaling as you move back (figures 24.10a & b). Try putting your hands underneath your knees and rocking up to a seated position and back down again. If you can’t get up to sitting, that’s okay.

Michael says that this is traditionally a pose of self-nurturing, like giving yourself a hug.

OTHER YOGIC IDEAS

Reclined Cobbler’s pose (Supta Baddha Konasana) is a restorative pose that allows the abdominal muscles to relax almost completely and is considered soothing for intestinal conditions. It can also be a profoundly relaxing and calming pose to the nervous system, particularly if you hold it for ten minutes or longer. Supporting the thighs increases the ability of the muscles around the groin to let go, further facilitating abdominal relaxation (see Chapter 18). Inversions, supported (restorative) like Chair Shoulderstand (see Chapter 15) or regular versions, may also be particularly helpful for constipation, both by reversing the effects of gravity on the body and because they can be deeply relaxing.

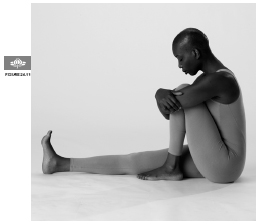

EXERCISE #11. SEATED FORWARD BEND, three to four breaths. Start by sitting with your legs stretched in front of you. Bend your left leg and place your left foot on the mat outside of your right knee (not inside as shown). Cradle your bent leg in your arms, as you sit up tall, lengthening your back. On your next exhalation, bend forward from your hips just an inch or two, reaching with your chin toward your foot. Breathe and then come farther forward still cradling your leg (figure 24.11) until you find your edge. Stay a few breaths. To come out of the pose, inhale and roll back up. Take your arms behind you and lean back, releasing your head if you like. Shake out your legs and notice how you feel. Repeat on the other side.

EXERCISE #12. MINDFULNESS MEDITATION, five to ten minutes. Sit in a comfortable, upright position, either on the floor or on a chair. For the first minute, simply become a witness to your thoughts. Michael says one way to do this is to imagine your thoughts as little boats sailing across a lake, coming in from one side and disappearing out the other. As a thought comes in, simply watch it. Put it in the little boat, and let it sail by and out the other side. In doing that, you’re watching the thought, acknowledging it, and letting go of it. If you prefer to use a different image, that’s fine. Just do whatever works for you. If it helps, you can focus on your breath, just noticing the breath move in and out, and as you do so, watching the mind’s eye.

In addition to taking the weekly class, Michael asked the students to practice for one hour at least six days a week. In each practice session, they were asked to do both some asana as well as meditation.

OTHER YOGIC IDEAS

The Viniyoga pose Apanasana can be soothing for the abdominal region and may be helpful for both diarrhea and constipation. To do the pose, lie on your back, bend your knees, and place each hand on its respective knee. As you exhale, gently bring your knees in toward the chest (left). As you inhale, let the knees drop back to their original position (right). Make the movements slow and deliberate so that they last the entire length of the breath. This exercise can be repeated several times.

Contraindications, Special Considerations, and Modifications

For people with diarrhea, certain yoga practices, such as strong abdominal twists, should be avoided, as they can increase intestinal activity, potentially worsening symptoms. These poses may also be problematic for people with constipation, although gentle twisting may be beneficial. As always with yoga, you need to adjust your practice to how you’re feeling. If you’re more symptomatic than usual, you may need to back off in favor of gentler and more meditative practices.

A Holistic Approach to Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Several types of food can exacerbate IBS symptoms, including fatty and fried foods, foods containing wheat, carbonated beverages, chocolate, caffeine, and some vegetables including cabbage, broccoli, and beans. Let your experience guide you.

Several types of food can exacerbate IBS symptoms, including fatty and fried foods, foods containing wheat, carbonated beverages, chocolate, caffeine, and some vegetables including cabbage, broccoli, and beans. Let your experience guide you.

A study found that when IBS patients changed their diet and excluded beef and all cereals except rice-based ones, cut back on citrus fruits, caffeine, and yeast, and used soy products instead of dairy, they had less abdominal pain, fatigue, diarrhea, and constipation.

A study found that when IBS patients changed their diet and excluded beef and all cereals except rice-based ones, cut back on citrus fruits, caffeine, and yeast, and used soy products instead of dairy, they had less abdominal pain, fatigue, diarrhea, and constipation.

Food additives such as monosodium glutamate (MSG) and the artificial sweetener Aspartame can trigger IBS symptoms.

Food additives such as monosodium glutamate (MSG) and the artificial sweetener Aspartame can trigger IBS symptoms.

To reduce gas, avoid carbonated beverages, don’t chew gum, and watch your consumption of beans, grapes, and raisins.

To reduce gas, avoid carbonated beverages, don’t chew gum, and watch your consumption of beans, grapes, and raisins.

Avoid sugarless gum if it contains sorbitol, a sweetener that can cause diarrhea.

Avoid sugarless gum if it contains sorbitol, a sweetener that can cause diarrhea.

Soluble fiber can be very helpful for people with IBS whose predominant symptoms include constipation, and for some people with diarrhea. Fruits, vegetables, and whole grains are rich in fiber, particularly soluble fiber. If you start adding fiber to your diet, do so slowly over several weeks and be sure to drink plenty of additional water.

Soluble fiber can be very helpful for people with IBS whose predominant symptoms include constipation, and for some people with diarrhea. Fruits, vegetables, and whole grains are rich in fiber, particularly soluble fiber. If you start adding fiber to your diet, do so slowly over several weeks and be sure to drink plenty of additional water.

If you don’t get enough fiber from dietary sources, try psyllium, a natural source of soluble fiber.

If you don’t get enough fiber from dietary sources, try psyllium, a natural source of soluble fiber.

Avoid insoluble fiber, which is found in bran, eggplant skins, and bell peppers. It can make IBS symptoms worse.

Avoid insoluble fiber, which is found in bran, eggplant skins, and bell peppers. It can make IBS symptoms worse.

Digestive enzymes are safe and appear to effectively reduce gas. For those who are vegetarians, health food stores sell enzymes derived entirely from plant sources, such as papaya.

Digestive enzymes are safe and appear to effectively reduce gas. For those who are vegetarians, health food stores sell enzymes derived entirely from plant sources, such as papaya.

Probiotics, essentially natural healthy bacteria like acidophilus in supplement form, appear to be very safe and possibly helpful for IBS.

Probiotics, essentially natural healthy bacteria like acidophilus in supplement form, appear to be very safe and possibly helpful for IBS.

Tricyclic antidepressant drugs like desipramine, typically prescribed at one-half to one-third the typical dose used for depression, may help in IBS by modulating pain sensations in the central nervous system. Since tricyclics are often constipating, this treatment may be particularly useful for individuals whose IBS is marked by frequent diarrhea.

Tricyclic antidepressant drugs like desipramine, typically prescribed at one-half to one-third the typical dose used for depression, may help in IBS by modulating pain sensations in the central nervous system. Since tricyclics are often constipating, this treatment may be particularly useful for individuals whose IBS is marked by frequent diarrhea.

People with diarrhea can get symptomatic relief with the antidiarrheal medication loperamide (Imodium).

People with diarrhea can get symptomatic relief with the antidiarrheal medication loperamide (Imodium).

Peppermint is an herb that relaxes the smooth muscle of the bowel wall and can help ease symptoms such as cramping, abdominal distention, and the frequency of bowel movements. Enteric-coated capsules containing peppermint oil are very safe, don’t cause the heartburn of non-coated peppermint oil or peppermint teas, and have been found to be effective.

Peppermint is an herb that relaxes the smooth muscle of the bowel wall and can help ease symptoms such as cramping, abdominal distention, and the frequency of bowel movements. Enteric-coated capsules containing peppermint oil are very safe, don’t cause the heartburn of non-coated peppermint oil or peppermint teas, and have been found to be effective.

Acupuncture is safe and there is some evidence that it can help with IBS.

Acupuncture is safe and there is some evidence that it can help with IBS.

A randomized controlled study published in JAMA found that treatment with a combination of Chinese herbs significantly improved IBS symptoms. While both standardized and individualized herbal combinations proved effective in the short term, fourteen weeks after the end of treatment, those who took the personalized prescription maintained greater improvement.

A randomized controlled study published in JAMA found that treatment with a combination of Chinese herbs significantly improved IBS symptoms. While both standardized and individualized herbal combinations proved effective in the short term, fourteen weeks after the end of treatment, those who took the personalized prescription maintained greater improvement.

When Michael Faber began the eight-week program, he found it very difficult, partly because of how much anxiety he had about his health, and about how the foods he ate were affecting it. He realized at one point during his meditation practice that he was worrying about how much he was worrying. Then, he says, “I realized that me noticing that I was worrying about worrying was actually part of the practice. As I was able to see that more and more, a lot of the anxiety and fears started to dissolve.” Seeing his worries as just thoughts that he could observe and let go of “was very freeing.”

Through the program, Michael came to realize that the tension he felt in his mind was also present in his breathing. “It’s often very shallow and rushed, which parallels my mind, which wants to do, do, do, and go, go, go.” When he slowed his breath during sitting meditation, he noticed his heart was also slowing down. Through the yoga postures, he discovered that he held a lot of tension in his body, including in his throat and abdomen. “I started noticing that, through the practice, that was changing.”

Michael Lee observed the changes in Michael Faber. “He experienced an incredible degree of relaxation. What he reported to the group was that he had never before been able to let himself go that much.” During his time at the workshop, his symptoms, which had been very bad before he started, almost disappeared.

However, he found it challenging to stick with the practice, even though its benefits were so significant. “I guess I’ve struggled with having the discipline about sitting every day, doing yoga every day.” Part of the problem is that he’s always found satisfaction in achievement but when he’s doing yoga or meditating, he always feels he should be doing something else—which, he concedes, “is on some level precisely why I need to practice.”

The program, he says, helped him see the value in taking time for himself, “just doing nothing, just relaxing next to a river—that downtime that I didn’t necessarily give myself before. In the past I really pushed myself beyond what was really healthy.”

Summing it all up, he says that his symptoms recur, though in a milder form, when he doesn’t do his practice, and they abate when he does. So he’s trying to make the practice a regular part of his life. “It’s kind of a work in progress, I guess.”