CHAPTER 26

MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS (MS)

When ERIC SMALL says he comes from a long line of horse traders, he means it literally. From a very early age Eric learned how to look a horse in the mouth. “You never believed what the owner told you; you had to make your own evaluation.” It was under his horse-trading father’s tutelage that Eric first became a teacher—at the age of six. “My father would put me on a box in the middle of the ring—a little kid, blond hair, big, thick glasses, skinny as a rail—and I could teach people how to ride horses. And I could project my voice. I knew what to look for.” When he began practicing yoga more than fifty years ago after developing MS at the age of twenty-two, the transition to teaching was natural. It was what he’d been doing all his life. His commitment to teaching yoga became even stronger when he studied with B. K. S. Iyengar, whose work forms the basis of what he now gives to his students. Eric says Iyengar’s approach is so powerful that “you don’t want to keep this to yourself.” He runs the Beverly Hills Iyengar Yoga Studio, is the coauthor of Yoga and Multiple Sclerosis, and is featured in the video Yoga with Eric Small. Eric and his wife, Flora Thornton, have funded two major yoga programs, The Eric Small Adaptive Iyengar Yoga Program, available nationally through local chapters of the MS Society, and The Eric Small Living Well with MS program, offered in Southern California.

When ERIC SMALL says he comes from a long line of horse traders, he means it literally. From a very early age Eric learned how to look a horse in the mouth. “You never believed what the owner told you; you had to make your own evaluation.” It was under his horse-trading father’s tutelage that Eric first became a teacher—at the age of six. “My father would put me on a box in the middle of the ring—a little kid, blond hair, big, thick glasses, skinny as a rail—and I could teach people how to ride horses. And I could project my voice. I knew what to look for.” When he began practicing yoga more than fifty years ago after developing MS at the age of twenty-two, the transition to teaching was natural. It was what he’d been doing all his life. His commitment to teaching yoga became even stronger when he studied with B. K. S. Iyengar, whose work forms the basis of what he now gives to his students. Eric says Iyengar’s approach is so powerful that “you don’t want to keep this to yourself.” He runs the Beverly Hills Iyengar Yoga Studio, is the coauthor of Yoga and Multiple Sclerosis, and is featured in the video Yoga with Eric Small. Eric and his wife, Flora Thornton, have funded two major yoga programs, The Eric Small Adaptive Iyengar Yoga Program, available nationally through local chapters of the MS Society, and The Eric Small Living Well with MS program, offered in Southern California.

By the time Jack Cullin (not his real name) was finally diagnosed with multiple sclerosis at the age of thirty-one, he had developed double vision, extreme fatigue, and a balance problem, as well as numbness in his legs and left arm. The diagnosis was made only after he had already had three flare-ups of symptoms. The symptoms abated again after the diagnosis, and the residual symptoms didn’t seem serious enough to move him to radically change his lifestyle. He continued to work in a very stressful, upper-level job as an account executive for a large marketing firm, which left him little time to spend with his wife and two young children.

However, eight months later, after yet another flare-up left him with some difficulty balancing while walking, a friend finally convinced him to try Eric’s class. He’d been resistant to his friend’s earlier suggestions, Eric says, because he thought yoga “was just some kind of mystical chanting or something.” In spite of his skepticism, he was curious and also perhaps just desperate enough to give yoga a shot.

Overview of Multiple Sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis is an autoimmune disease of unknown cause in which the immune system attacks the fatty tissue, known as myelin, which acts as insulation for nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord. Lacking myelin, nerve cells are inefficient at passing their messages down the line, and as a result, the functions those nerves serve can be affected. Recent evidence also suggests that the immune system attacks the nerve fibers themselves. For years, researchers have postulated that a viral infection results in an immune response that turns on the body, though the theory remains unproven. There is clearly also a genetic component, as the disease is more common in people who have an affected relative. People of northern European ancestry as well as those who grow up in cold climates are more likely to be affected.

The clinical course of MS is highly variable, from fairly mild to rapidly debilitating. The classic and most common form is what is known as relapsing-remitting MS. In this type, attacks result in discrete losses in nerve function, different from one attack to the next, which fully or partially disappear between attacks. This is the form of the disease that both Jack and Eric have. Less commonly, the disease progresses steadily without remissions. Sometimes, for unknown reasons, MS goes into long-term or permanent remission.

Symptoms from MS are extremely diverse, reflecting the different parts of the nervous system involved. Common symptoms include a clumsiness or loss of feeling in the arms and legs, difficulty with balance, a reduction in bowel or bladder control, and sexual dysfunction. Also common are blindness in one or both eyes due to involvement of the optic nerve, double vision like Jack experienced, painful contractions in muscles, overwhelming fatigue, emotional problems, and difficulty with thinking and memory.

There is no definitive test for MS. Making the diagnosis depends on taking a careful history of symptoms and looking at suggestive but not definitive findings on MRI scans and other tests. It is vital—particularly if you are contemplating drugs that have potentially serious side effects, cost thousands of dollars a year, and are meant to be long-term regimens—to be sure you truly have the disease. Experts debate how frequently MS is incorrectly diagnosed, but estimates vary from one-tenth to one-third of cases. If you have any doubt about your diagnosis, don’t hesitate to get a second and third opinion.

There is no definitive test for MS. Making the diagnosis depends on taking a careful history of symptoms and looking at suggestive but not definitive findings on MRI scans and other tests. It is vital—particularly if you are contemplating drugs that have potentially serious side effects, cost thousands of dollars a year, and are meant to be long-term regimens—to be sure you truly have the disease. Experts debate how frequently MS is incorrectly diagnosed, but estimates vary from one-tenth to one-third of cases. If you have any doubt about your diagnosis, don’t hesitate to get a second and third opinion.

How Yoga Fits In

There are a number of ways that yoga can help with MS. Though the idea remains controversial among some physicians, studies suggest that stress is an important factor in increasing the likelihood of developing the disease and in flare-ups after the initial onset. Precisely how stress causes these effects isn’t known, but it is hypothesized that elevated levels of the stress hormone cortisol increase levels of proinflammatory cytokines, internal messengers of the body’s immune system, which fuel inflammation and contribute to the destruction of the myelin lining of nerve fibers.

Beyond stress’s possible role in the physiology of MS, stress is certainly an offshoot of living with the disease, which can be very challenging. If only because yoga can be so effective at combating stress and depression, it can be useful medicine for those trying to cope with the illness, helping to improve quality of life both during and between flare-ups.

Yoga can help in other ways, too. Gaining heightened awareness of the body, breathing more deeply and regularly, improving balance and coordination, and learning to let go of holding in muscles—these are all areas where yoga practice, specifically the practice of asana and pranayama, can make a big difference. People with MS can develop contractures, areas where the connective tissue around joints tightens, leading to a loss in movement. Over time, a regular yoga practice and the slower, deeper breathing that comes with it can help reverse these detrimental changes.

Poor posture can contribute to muscle tightness and pain. Asana practice can improve posture as can a regular practice of pranayama and meditation. All of these practices appear to be useful in boosting mood, as well. A regular meditation practice may be particularly useful in helping with pain control (see Chapter 3).

The yogic tool of karma yoga, selfless service, may be useful, too. One study found that people with MS who volunteered to work on a telephone support line for other people with the disease noted significant improvements in their self-esteem, confidence, and mood. In that study, in fact, the volunteers showed greater benefits than those they counseled. Your local chapter of the MS Society may have information about volunteer opportunities, which, beyond any health benefits, provide social contacts in what can be an isolating disease.

The course of MS tends to be quite variable, and one of the beauties of yoga is that it can be adapted to meet the student’s changing needs. If fatigue is a problem, a more restorative practice can be used. If a particular limb is weak, props can be used to help the person do the poses with more ease. If balance is an issue, postures can be done standing against the wall or holding a chair for support. For people who are unable to stand, even with assistance, asana practice can be modified to accommodate them. Some breathing, guided meditation, and meditation practices can be done in bed if necessary. Sam Dworkis, who has had MS for a number of years, says yoga is about “learning how to accept what your body allows you to do at any given moment, and understanding that’s the reality.” If you think you’re not healthy enough or flexible enough to do yoga, he believes you’re focusing too much on what you can’t do, and not enough on what you can. “The thing that’s so interesting to me is that my yoga practice enables me to pay more attention to the things I do have control over.”

Yoga can also help build hope. Even though yoga can’t cure the disease, doing it can lessen your symptoms and enhance your sense of well-being, encouraging faith and maybe even optimism. When you realize you are feeling better as a direct result of something you have done, it gives you a sense of empowerment, because of the concrete steps you have taken to improve your own situation.

Yogic Tool: TAPAS. Tapas (see Chapter 1) is the dedication and discipline that fuels your yoga practice. Eric stresses that the key to success with yoga is the work you do. “I’m not interested in somebody coming here and dropping their body in front of me, and letting me do all the work. This is not what yoga is about. Yoga is what you do for yourself. And that’s a big step—a big step. You can easily say, ‘Oh, I can’t do this because I have MS. So I’ll just sit here and be helpless.’ Or, ‘If I do it for three weeks, will I be better?’ My requirements are that you meet me halfway. As much as I give you, you must also practice to give yourself.” The minimum amount of practice that Eric recommends is half an hour daily. “And they have to bring me their homework sheets indicating how much time they spent doing each one of the exercises.”

The Scientific Evidence

In a 2002 survey conducted by Oregon Health Sciences University (OHSU), 30 percent of the almost two thousand people with MS interviewed said they had taken yoga. Of that group, 57 percent reported that yoga was “very beneficial,” a better result than any MS drug elicited.

To date there is only one controlled study that has examined the effects of yoga on MS. Not surprisingly, Eric Small served as a consultant on the project. Led by Barry Oken, MD, a professor of neurology at OHSU, the study randomized sixty-nine people with different types of MS into three study groups for six months. The first group took part in a weekly Iyengar asana class specifically adapted for people with MS. The second group took a weekly exercise class using stationary bicycles. Members of the exercise group were given a stationary bike for home use, and those doing yoga were encouraged to practice at home every day in addition to the weekly class. Members of the third group continued their usual activities. Both the yoga and exercise interventions resulted in a statistically significant improvement in fatigue, one of the most prevalent and potentially debilitating symptoms of MS. Subjects in the yoga and exercise groups also reported a statistically significant improvement in their overall health. The researchers noted some improvement in mood, too, though the magnitude of the change wasn’t statistically significant.

Eric Small’s Approach

In the Yoga Sutras, Patanjali speaks of the need to balance effort and ease. Trying too hard either on or off your yoga mat can actually interfere with what you hope to achieve, a major problem for people with MS, who Eric says “are all type A personalities.” (See Chapter 19.) Wanting badly to keep up with those around them and to maintain appearances, “They all push themselves too hard.” Doing so, he believes, takes a toll on already taxed nervous systems, increasing stress. Eric says that even students who have tremors or sudden weaknesses often don’t want to use the props and supports he recommends. “They’re the tough ones,” he says. “Those are the people you need to slow down.”

Eric likes to put his new students with MS in restorative poses right away, particularly those who tend to try too hard. It slows them down and gives him a chance to evaluate them. One focus of his observations is how well the student follows instructions. “That gives you a fairly good idea of their cognitive function, and their retention of information. It also gives me an idea as to how the body has been affected by the disease—whether there’s a general weakness, specific weaknesses, spasms, what is the range of motion.”

Based on what he sees in those first restorative poses, Eric adjusts the program. If he notices a loss of range of motion in the hip, for example, he’ll use extra props to brace that area. For him it’s all about individualizing the therapy to the specific needs of the student. “You modify and modify, with blankets, other props, chairs, pillows, and belts, and blocks. You support, you keep supporting.” In addition to taking a case history, including flare-ups and residual symptoms, he finds out what medications they’re taking and does a hands-on assessment. He notices their posture and breathing; he even inspects the pattern of wear on their shoes.

On first examination, Eric saw that Jack appeared to be a relatively healthy man of average weight, with muscle tone that was average to above average—perhaps attributable to the fact that Jack had been a runner and hiker. Eric noticed that Jack listed dramatically toward the left, although Jack was not aware of it. This told him that Jack’s left side was the weak side. “I also noticed that he had a tendency to go forward and backward, almost imperceptibly,” an indication that Jack was struggling with his balance. This suggested to him that Jack had a problem with his inner ear. Because Jack had a suitable chair at home, Eric made liberal use of a chair prop in the routine he designed. He likes the support and the help with balance that chairs provide his MS students.

The sequence of poses and instructions that Eric provided for Jack follows. None of the poses are held longer than ten seconds, because he feels that when you are dealing with people who fatigue easily, have problems with balance, and often have short attention spans, the poses should be comfortable and quick. If fatigue becomes a problem, he allows for relaxation time between poses.

EXERCISE #1. CHANTING OM. Sit in a comfortable upright position on the floor or on a chair, and close your eyes. If you sit on a chair, place folded blankets on the seat of the chair (figure 26.1), or on the floor in front of the chair, depending on your height, so that your knees and hips are at the same level and your knees are directly over your ankles, with your feet flat on the floor. Inhale. On your exhalation begin making the sound “O” for several seconds. While continuing to exhale, close your lips and hum the “M” sound for a few more seconds. Repeat twice.

Eric asks students to make chanting of Om part of their home practice because he believes the vibrational component of the sound waves has therapeutic value, particularly with a neural disorder.

In all the asana Eric teaches, breath remains a major focus. “Any expansive movement is done on the inhalation, and any contraction is on the exhalation. Standard operating procedure.” For example, you inhale on moving into a backbend or raising the arms above the head, because these movements open the body and are considered expansive. You exhale on going into forward bends, which brings the body in on itself, and is considered a contraction.

In all the asana Eric teaches, breath remains a major focus. “Any expansive movement is done on the inhalation, and any contraction is on the exhalation. Standard operating procedure.” For example, you inhale on moving into a backbend or raising the arms above the head, because these movements open the body and are considered expansive. You exhale on going into forward bends, which brings the body in on itself, and is considered a contraction.

EXERCISE #2. COBBLER’S POSE (Baddha Konasana), in a chair. Set up for the pose by placing one or two bolsters or a second chair in front of your chair to support your feet. The stiffer you are, the lower the support should be. To come into the pose, sit upright on your chair, bend your knees, and bring the soles of your feet together on the prop. Allow your knees to gently drop to the side.

Due to some stiffness, Jack started with his feet on a bolster placed on the floor in front of the chair (figure 26.2a) and later went up to two bolsters. After three months of regular practice, he was easily able to put his feet up onto the seat of a second chair and to drop his knees to at least 60 degrees (figure 26.2b).

EXERCISE #3. SUPPORTED WARRIOR II (Virabhadrasana II), holding a strap. To set up for the pose, place a chair on a yoga mat and have a looped yoga strap nearby. Now step your right foot through the back of the chair, and bend your knee so your thigh is supported by the seat of the chair and your front foot is on the floor. If balance is a problem, turn the chair sideways (figure 26.3), since putting the foot through the back could lead to a fall. Extend your left leg behind you and turn the left foot slightly in. Putting your weight more onto the leg on the chair seat may allow you to bring your legs into better alignment. Next, extend your arms to the sides, holding the strap looped around the right hand between your thumb and your palm, extending around the back of your neck and between the thumb and palm of your left hand. When the belt crosses your neck, it should pass over your seventh cervical vertebra (C7, the prominent bump on the lower part of the back of your neck). Do a little “push-pull” between your two hands. Repeat the pose on the other side.

The strap, says Eric, is “to steady the nerves, where the nerves come out of the spine.” You are also supporting C7 and your arms so your arms don’t get the shakes.

For his MS students Eric doesn’t use the thin straps common in Iyengar yoga studios. Instead he recommends wider straps. Eric says, “The more contact you have on the body, the more peripheral nerve response you receive. That’s very important.” He also prefers straps that have a luggage clip as opposed to a buckle, because they’re easier to put on and take off quickly.

For his MS students Eric doesn’t use the thin straps common in Iyengar yoga studios. Instead he recommends wider straps. Eric says, “The more contact you have on the body, the more peripheral nerve response you receive. That’s very important.” He also prefers straps that have a luggage clip as opposed to a buckle, because they’re easier to put on and take off quickly.

EXERCISE #4. SUPPORTED EXTENDED SIDE ANGLE POSE (Utthita Parsvakonasana), using two chairs. To set up for the pose, place two chairs on your yoga mat, one next to the other.

Sit on the left chair, place your right forearm and palm on the seat of the right chair, and lean into them. Turn your right leg out to the right and bend the right knee. Use your other arm to hold on to the back of the first chair (figure 26.4).

“That opens the chest, gets the kidneys working, releases the pressure of the liver, and stimulates the transverse colon and the descending colon.” Repeat the pose on the other side.

In poses that include an element of twisting like Triangle pose and Extended Side Angle pose (exercises #4 and #5), Eric has his students keep the head in neutral alignment. Because he doesn’t know where the students have areas of demyelination (plaques), he avoids having them twist their necks, to ensure that they do not further compromise already limited nerve conduction. Not twisting the neck also allows easier passage of the breath. He instructs them that rather than turning the head to the side, they should always keep the nose pointing in the same direction as the chest.

In poses that include an element of twisting like Triangle pose and Extended Side Angle pose (exercises #4 and #5), Eric has his students keep the head in neutral alignment. Because he doesn’t know where the students have areas of demyelination (plaques), he avoids having them twist their necks, to ensure that they do not further compromise already limited nerve conduction. Not twisting the neck also allows easier passage of the breath. He instructs them that rather than turning the head to the side, they should always keep the nose pointing in the same direction as the chest.

EXERCISE #5. SUPPORTED TRIANGLE POSE (Trikonasana) at the wall, using chair. Set up for the pose by placing your mat next to a wall, with a chair on your mat, and the back of the chair against the wall. Extend your right leg out to the side as best you can, with your foot turned out 90 degrees. Then step your left leg out to the left side with the foot turned slightly in. Lengthen the right side of your torso, bend from the right hip, and place your right hand on the seat of the chair (figure 26.5). Lengthen your left arm straight up. If this is not possible, place your hand on your hip, as shown. Allow your rib cage to rotate toward the ceiling. To come out of the pose, reverse your steps. Repeat the pose on the other side.

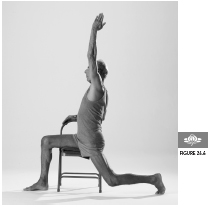

EXERCISE #6. WARRIOR I (VirabhadrasanaI), using chair. Set up for the pose by placing a chair sideways on the mat. Stand facing the side of the chair, and bring your right leg over the seat and put your foot on the floor. Bend your knee to 90 degrees. Lift your left heel and turn your left leg so that the front of the thigh is touching the edge of the chair seat. Straighten your left leg as much as possible. Holding your right hand on the back of the chair, raise your left hand overhead. Using your hand on the chair for leverage, lift your chest (figure 26.6). Step out of the pose. Repeat the pose on the other side.

EXERCISE #7. REVOLVED SIDE ANGLE POSE (Parivrtta Parsvakonasana), using the chair. Sit down on a chair, with your legs straddling the sides and your feet touching the floor. Turn to the right so that your left leg is behind you and the top of your left thigh is touching the chair seat. Bend your right knee to 90 degrees. Place your left elbow on the outside edge of your right knee. Hold the back of the chair with your right hand while keeping your head facing forward. Use the motion of the left elbow to open your chest, continuing to face forward with your head. Repeat the pose on the other side.

EXERCISE #8. SEATED FORWARD BEND (Paschimottanasana), using two chairs. Set up for the pose by placing one chair against a wall with a second chair facing it. Sit on the chair that’s touching the wall. Extend your legs out toward the second chair and place your hands on the seat of the second chair. Then push the second chair forward until you feel a mild stretch of your hamstrings (back thigh muscles).

EXERCISE #9. SEATED TWIST (BharadvajasanaI), with a chair. Sit sideways on the chair facing to the right, with the knees and feet hips’ width apart. Turn to your right and use both hands to take hold of the back of the chair, using your arms to help you twist. With each inhalation, lengthen your spine. With each exhalation, turn from your navel and twist a little more deeply into the pose, but keep your head facing the same direction as your chest. Keep your shoulders level. To come out of the pose, swing your legs to the other side of the chair. Repeat the pose on the other side.

EXERCISE #10. SUPPORTED FRONT BODY STRETCH (Purvottanasana), on two chairs. Set up for the pose by placing one chair with its back about two feet from the wall and a second chair facing the first. Sit backward on the chair farther from the wall and put your legs through the back of the other chair (figure 26.10a), then slide your buttocks onto the other chair, bend your knees, and brace your feet against the wall. From this position, lie back onto the two chairs with your head near the back of the seat of the second chair. You can lay your head directly on the seat of the second chair, or if your chin is higher than your forehead when your head is flat, place a support under your head. Holding on to the first chair with your hands, use your legs to push away from the wall, until they are straight. From there, thread your arms through the back of the second chair and stretch them toward the center of the room (figure 26.10b).

Normally in this pose Eric does not use padding on the chairs but if a student finds the surface too hard, he will put a sticky mat and a blanket on the chair seat. However, in general, he prefers not to because he wants students to be able to slide their buttocks back and forth, which is hard to do with a blanket or a sticky mat.

“It’s a very gentle, easily accomplished backbend,” Eric says. He chose this supported backbend for Jack to alleviate the depression he suspected Jack had, and because he believed it would improve Jack’s digestion.

EXERCISE #11. SUPPORTED RELAXATION POSE (Savasana), with legs on a chair. Set up for the pose by placing a chair sideways on your mat. (If you have long legs, you may need to use two chairs.) Fold a blanket into a long rectangle and place it perpendicular to the chair. Sit on the blanket with your buttocks near the chair and swing your legs up onto the chair, resting your calves on the chair seat or on a folded blanket on top of the seat. Your thighs should be perpendicular to the floor and your calves parallel to it. Now lie back on the folded blanket so that it supports your entire spine, from your hips to your head. If you have difficulty reaching the floor with your arms, place blankets under your arms, from the shoulder to the fingertips. If your chin is higher than your forehead when you lie back, place an additional blanket under your head.

Eric says, “With MS, any time the student is lying on the floor, or in an inversion, the spine and the head have to be supported.”

EXERCISE #12. BREATH AWARENESS PRANAYAMA, three minutes. Place a bolster lengthwise on your mat. Sit in front of it (not on it), and loop a strap around your thighs. If necessary, place a folded blanket under your head, as shown, so that your chin is lower than your forehead when you are in the pose. Lie back. Now tune in to the sensation of the breath in your nose. Encourage your inhalation to come at the base of your nostrils and the exhalation to be through the tip of your nostrils. In this relaxed breath do not puff up your abdomen as is done in belly breathing. Breathe smoothly in and out with no retention of breath whatsoever.

Eric says that he teaches this pranayama in the very first lesson to MS students because he finds it so beneficial. As with Savasana, all pranayama he teaches to these students is done in a supported reclined position. As his students progress with pranayama over the coming weeks, he moves from the smooth breath described above to Ujjayi, making a gentle sibilant sound on both the inhalation and exhalation (see Chapter 1). The instructions for the abdomen are the same.

On days when Jack is exhausted Eric recommends he switch to a more restorative practice, including such poses as Legs-Up-the-Wall pose (Viparita Karani, see Chapter 3) and Reclined Cobbler’s pose (Supta Baddha Konasana, see Chapter 18). In both of these poses, he often suggests placing sandbags on the shoulders to facilitate a deeper level of relaxation. Weighted sandbags strategically placed can also encourage spastically contracted muscles to let go. “I use a lot of weights with MS,” Eric says. He might, for example, put sandbags on the hands when a student is on the floor in Reclined Cobbler’s pose or in Relaxation pose. At other times he puts weights on students’ hands, arms, groin muscles, and even on their heads. Since sandbags placed incorrectly can cause harm, they should be used only under the guidance of a seasoned teacher.

Eric strongly believes that readers wishing to implement any of his suggestions should do so under the guidance of an experienced, certified Iyengar teacher. Although some teachers claim to be certified by him, he says that while he does give workshops on teaching yoga to people with MS, he does not certify participants.

Eric strongly believes that readers wishing to implement any of his suggestions should do so under the guidance of an experienced, certified Iyengar teacher. Although some teachers claim to be certified by him, he says that while he does give workshops on teaching yoga to people with MS, he does not certify participants.

Contraindications, Special Considerations, and Modifications

One of the biggest risks to people with MS is overheating, which can make symptoms worse because it slows nerve conduction. For this reason, yoga in hot rooms and vigorous styles that heat up the body are generally contraindicated for people with the disease. Eric keeps the room temperature at 67 degrees and watches activity levels very carefully. During the summer, he doesn’t teach any afternoon classes because it’s too hot in Southern California, where he lives. If the weather is very warm, or if a student is having an MS flare-up or is very fatigued (a common experience for Eric’s students because with public access transportation it may take them hours to get to the class), he’ll lead a primarily restorative practice.

People with MS and other neurological conditions should avoid any poses that require a sudden burst of energy to come into the pose, like the full backbend Upward Bow (Urdhva Dhanurasana) or Handstand. Some people with MS find that exercise can increase problems with muscle spasticity. Gently and slowly warming up and focusing on maintaining smooth, deep, slow breathing throughout the practice can help prevent this problem.

A Holistic Approach to Multiple Sclerosis

Studies suggest that pain is undertreated in people with MS. Since normal pain relievers are not always effective, doctors often suggest tricyclic antidepressants (prescribed at lower doses than typically used for depression) and some medications normally used to treat epilepsy. Often, a combination of different medications proves more effective than any single drug alone.

Studies suggest that pain is undertreated in people with MS. Since normal pain relievers are not always effective, doctors often suggest tricyclic antidepressants (prescribed at lower doses than typically used for depression) and some medications normally used to treat epilepsy. Often, a combination of different medications proves more effective than any single drug alone.

Nondrug measures like meditation and cognitive-behavior therapy to learn coping skills may lessen the need for pain-relieving drugs or allow you to use smaller doses.

Nondrug measures like meditation and cognitive-behavior therapy to learn coping skills may lessen the need for pain-relieving drugs or allow you to use smaller doses.

In MS patients who are depressed, treatment with either medication or psychotherapy has been shown to decrease levels of chemical messengers (proinflammatory cytokines) that fuel inflammation. Thus reducing depression may have a beneficial effect on the disease process itself. Treating depression also appears to reduce fatigue (see Chapter 15).

In MS patients who are depressed, treatment with either medication or psychotherapy has been shown to decrease levels of chemical messengers (proinflammatory cytokines) that fuel inflammation. Thus reducing depression may have a beneficial effect on the disease process itself. Treating depression also appears to reduce fatigue (see Chapter 15).

A diet high in vegetables and fruits and whole grains fights inflammation and has other healing properties (see Chapter 4).

A diet high in vegetables and fruits and whole grains fights inflammation and has other healing properties (see Chapter 4).

Saturated fats and trans-fatty acids, which are found in many processed foods, appear to promote inflammation and should be avoided. Omega-3 fatty acids damp down inflammation (for more details, see Chapter 9).

Saturated fats and trans-fatty acids, which are found in many processed foods, appear to promote inflammation and should be avoided. Omega-3 fatty acids damp down inflammation (for more details, see Chapter 9).

Ginger and the Indian spice turmeric have anti-inflammatory properties. They can be used in cooking or taken as supplements.

Ginger and the Indian spice turmeric have anti-inflammatory properties. They can be used in cooking or taken as supplements.

The combination of dietary fiber and plenty of water can help prevent constipation, especially if combined with regular asana practice, walking, or other forms of exercise.

The combination of dietary fiber and plenty of water can help prevent constipation, especially if combined with regular asana practice, walking, or other forms of exercise.

The Ayurvedic herb triphala is also useful to improve digestion. Although you can find this in health food stores and it’s generally very safe, the best approach is to consult an Ayurvedic practitioner.

The Ayurvedic herb triphala is also useful to improve digestion. Although you can find this in health food stores and it’s generally very safe, the best approach is to consult an Ayurvedic practitioner.

Many patients with MS find some relief using medicinal marijuana for such symptoms as pain, muscle spasticity, and tremors, though using the herb, with certain exceptions, is illegal.

Many patients with MS find some relief using medicinal marijuana for such symptoms as pain, muscle spasticity, and tremors, though using the herb, with certain exceptions, is illegal.

Many people with MS find traditional Chinese medicine of benefit.

Many people with MS find traditional Chinese medicine of benefit.

Massage and other forms of bodywork are relaxing, can help with muscle spasticity, and are a valuable complement to asana practice.

Massage and other forms of bodywork are relaxing, can help with muscle spasticity, and are a valuable complement to asana practice.

Since community can be therapeutic with MS and many people with the disease have limited mobility, the Internet can be a useful tool. Online support groups for MS are abundant.

Since community can be therapeutic with MS and many people with the disease have limited mobility, the Internet can be a useful tool. Online support groups for MS are abundant.

Despite his initial misgivings about yoga, Jack was so moved emotionally by his first exposure to Eric’s class that at the end of the hour he told Eric, “I’m yours.” He started coming regularly to the weekly class.

Many MS students find Eric, who has had MS for over fifty years, to be an inspiration. When they see how active and productive he is, “they suddenly make the connection that if I’m fifty years down the road from them, and I’m doing what I’m doing, why not get on the bandwagon?”

Beyond asana and pranayama, Eric encourages the kind of yogic self-study that can bring about changes in attitudes and behavior. During class he tells students, “We all have to take responsibility for where we are and what we do. If you are in a very stressful employment situation, why are you wasting your time in here? Because nothing’s going to get better unless you make some life changes.” Jack appears to have gotten the message. “Jack has been with me for four years now. He’s still in the same field, but now he’s in business for himself, so he has much less stress, and he can pace his day according to how he functions.” Because working for himself has allowed Jack to set his own schedule, he is able to arrange his work so that he and his wife both have enough time to spend with their children and with each other.

Another part of the stress-reduction strategy Eric recommends is honesty, the yama that Patanjali called satya (see Chapter 1). “In most cases, people do not tell their employers that they have MS. They try to get through the best way they can. But I tell them, You are protected by the Americans with Disabilities Act. They cannot discriminate against you because you’ve contracted a disease. You have to go back and tell your employers, or your supervisor, exactly what your situation is, exactly what you think you can do. And once you get rid of this deep dark secret, then you reduce 80 percent of your stress.”

Eric says that since Jack started yoga, he has put on around ten pounds of muscle and looks good. Eric describes Jack’s mood when they started working together as “sour, strident, worried, and depressed, but he has a wonderful attitude now.” Eric adds, “He’s gained flexibility through his practice and his sex life improved, which was another issue.” He believes the opening of the pelvis that comes through regular practice helps both men and women in this regard.

Jack also seems to have embraced the philosophy of karma yoga. “He is very eager to pass the word around, and he does volunteer work for the MS Society,” Eric says. “As soon as you start giving to other people, your problems aren’t as serious. So start listening to other people’s problems, and yours in perspective are practically nothing.”

In essence, Eric asks of his students what his teacher B. K. S. Iyengar asked of him. He summarizes it: “Take responsibility. Develop your own practice, learn where your strengths are, learn where your fears are, face your fears, develop strength in your weaknesses.”