Brown Hares have oversized ears, large eyes, and long, sensitive whiskers: adaptations for avoiding predators.

Brown Hares have oversized ears, large eyes, and long, sensitive whiskers: adaptations for avoiding predators.

Meet the Hares

Hares, though not often seen, are characteristic animals that are known and loved by many. There is something magical about hares – they feature in folklore, art, children’s books and poetry. The hare is a symbol of fertility, resurrection and immortality, perhaps because it has the ability to pop up unexpectedly as though suddenly born or reborn, appearing out of nowhere, only to disappear from view by sprinting away.

Only a handful of our mammal species are familiar to most of us, and not many people are lucky enough to see wild mammals regularly. Depending on where you live, you might see Foxes, squirrels, rats, mice, deer, bats and Rabbits. Though they are more rarely seen, hares are among our most distinctive mammals. Some might describe them as ungainly, long-legged rabbit-like animals with oversized ears. Hares are similar to Rabbits, but they are bigger and faster, and also more timid, elusive and elegant than the much more familiar Rabbits. The hare is an unusual species in that it breeds quickly and does not live long, but is relatively large (see Speedy lifestyles). It is also a game animal and food source that is eaten by humans and other animals (see Eat or Be Eaten). In some parts of the world, hares are invasive pests, causing harm to fragile ecosystems (see Conservation of Hares). In others, the conservation of hares presents a paradox: why are hares threatened by intensive farming, though they thrive in arable areas?

Arable fields provide food and shelter for hares, while field margins allow them to add diversity to their diet.

The ‘common hare’, or Brown Hare, as depicted by the artist A. Thorburn in British Mammals, published in 1920.

A Mountain Hare in its winter coat is well camouflaged in snow. Illustration by A. Thorburn, British Mammals, 1920.

Two (or more) British species

Two species of hare are widespread in Europe: the Brown (or European) Hare and the Mountain Hare. There are 15 European subspecies of Mountain Hare. The Mountain Hares in the British Isles belong to two subspecies: one is found in Scotland and the Peak District; the other is found in Ireland, is called the Irish Hare and may in fact be a separate species. There are also at least 16 subspecies of Brown Hare, which differ in colour, size, and skull and tooth shape, but their relationships and distributions are still being clarified by scientists. This book focusses on the Brown Hare, the Scottish Mountain Hare and the Irish Hare. These species are similar enough to be difficult to identify when seen in isolation but, as they are found in different areas and habitats, you are unlikely to confuse them. If you were to see two of these hares side by side – which could happen only with a great deal of luck or skill, and only in a handful of locations – you could tell them apart easily enough with careful observation.

left: The Brown Hare is distinctly reddish-brown. In summer, the Mountain Hare (right) is similar in colour, but its winter coat may be partly or entirely white. This individual, photographed in spring, is moulting to become brown again.

The Brown Hare

The long back legs of Brown Hares allow them to move swiftly.

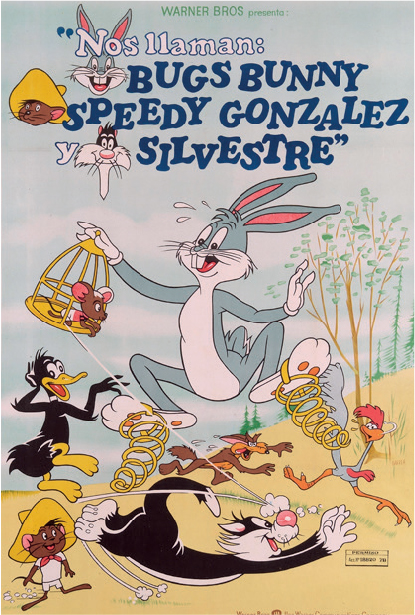

The Brown Hare (Lepus europaeus), though fairly common on farmland in Europe, is tricky to see because it is secretive, elusive and nocturnal or crepuscular. Adult Brown Hares in England weigh on average 3.5kg (7¾lb), as much as a domestic cat, and are about 55cm (22in) long from nose to tail. Their back feet are very large, at about 15cm (6in) long. The back legs are much longer and larger than their front legs; as a result, hares have a peculiar galloping gait, in which the front feet land first and the hind feet pass outside the front feet and land in front of them. The ears appear to be oversized at about 10cm (4in) long. If you fold the ears of a Brown Hare forward, over the top of its nose, the ears stick out a little beyond the tip of the nose. This is not the case with a European Rabbit, or even with an Irish or Mountain Hare. What immediately springs to mind, of course, is the astonishing fact that Bugs Bunny is actually a hare!

Bugs Bunny’s long ears and limbs make him look more like a hare or a jackrabbit than a rabbit.

Brown Hares live their whole lives above ground, creating forms or seats (depressions in the ground or vegetation) to shelter in during the day. They rely on speed to escape from their main natural enemy, the Red Fox, and from other predators, as hares do not use burrows. Brown Hares are mainly solitary, though they come together to mate and sometimes to feed. During the mating season, several potential suitors (males, also called bucks) follow a female (or doe) around, and females who are not ready to mate ‘box’ the males, simultaneously pushing them away and testing their strength.

Each hair in the fur of Brown Hare has bands of several colours, giving the animal a brindled appearance.

Though Brown Hares may look patchy and scruffy when they moult (in spring and autumn), their coats otherwise change little over their lives. They are born with fur very close in colour to the adult coat and their summer and winter coats look similar. When you glimpse a Brown Hare, especially in sunlight, the most striking identification feature is its colour. It is distinctly reddish brown on the back, though the red is more patchy and more brindled or grizzled than the red of a Fox, because each individual hair is banded in different colours along its length. The coat becomes yellower on the flanks, on the sides of the face and on the inner limbs. The belly is creamy white; the tail white with black on top. Wild European Rabbits, on the other hand, appear much more even in colour, and are more greyish brown than reddish brown. There are grey, black, white and sandy-coloured forms of the Brown Hare, but they are very rare.

A Brown Hare keeping watch from its form. From a distance, it can resemble a clump of mud.

In sunlight, Brown Hares usually settle in their forms, where they are hard to spot as they are well camouflaged and motionless. Try scanning a field with binoculars, looking for something that resembles a lump of manure or mud – it might turn out to be a hare. Once you spot a hare in its form, you may be able to approach quite closely and watch it sink gradually lower and lower into the ground, until you get so close that the hare finally decides to run for it. Then you will see the back end of the hare disappearing very quickly and, if you can find it, you may see the still warm and cosy-looking form. Usually the form provides the hare with a good view over any open areas. If you watch Brown Hares when they are most likely to be active and visible, at dawn or dusk and in low light, the pale margins of their downturned tails and the back of their ears stand out.

Range and habitats

The Brown Hare is found throughout the UK, including on several surrounding islands. It has a wide native (natural) range in Europe and Asia, stretching as far as Lake Baikal in Siberia. Over the years, Brown Hares have been caught (or bred in captivity), boxed up, moved around and released into the wild many times, mainly to create new populations or to increase existing populations for hunting. Introduced populations of Brown Hares now live outside their native range, in Northern Ireland, Siberia, Finland, Sweden, eastern Canada, north-eastern USA, southern South America, Australia, New Zealand, Barbados, Réunion (near Madagascar), the Bahamas and the Falkland Islands. The Brown Hare is also an invasive non-native species in many places.

In Australia, there were 30 known attempts to introduce Brown Hares, of which 14 were successful. Brown Hares became established in Tasmania in 1837 and on the mainland in 1855. They spread naturally at a rate of less than 2km (1¼ miles) per year, and in 1867 the Acclimatisation Society of Victoria began distributing hares to the landed gentry throughout Victoria and New South Wales. The last known introduction of Brown Hares to Australia was in 1872. By 1900, they had reached the Queensland border and had become agricultural pests in Victoria and New South Wales.

Brown Hare world distribution map, showing the native and introduced range, and the British Isles, where it is unknown whether the Brown Hare is native or introduced. The arrows indicate small introduced populations in Ireland, Barbados and Réunion.

Though the Brown Hare is classed as Near Threatened or Threatened in several individual countries, it is classed as Least Concern in the Red List of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). This indicates that globally, it is not considered threatened, vulnerable or endangered. Like other hare species, Brown Hares rely on being able to see predators, and avoid them by running fast, so they prefer flat open habitats with short vegetation, especially at night, when they are feeding. They can be found in saltmarshes, arid areas, moorland, alpine grassland, steppe (semi-arid grassland), pampas (South American fertile plains) and sand dunes. However, in Europe they are most common in arable areas used for cereal growing.

Brown Hares in Europe generally like arable crops, but need other habitats for shelter and food at different times of year.

Brown Hares do need some permanent cover, and leverets (young hares) survive better in mixed agricultural areas than in cereal monocultures. Therefore, large-scale intensive farming, with a low diversity of crops and large fields, is less suitable for them than farming that provides food and shelter all year round in small fields. Brown Hares like strips of uncultivated land in arable fields; creating such strips and windbreaks, and increasing crop diversity, can lead to dramatic increases in numbers of hares. Woods, shelterbelts and hedgerows are used by Brown Hares for resting and occasional feeding during the day, particularly in winter. They will feed in pasture all year round, but may do so more in summer when cereal crops are no longer edible for hares. High densities of cattle and sheep may deter Brown Hares.

The Brown Hare can tolerate mean annual temperatures of 3–30°C (37–86°F) and annual rainfall of 200–1,200mm (7¾–47in), and occupies elevations of up to 2,500m (8,200ft) above sea level.

Introduced species and acclimatisation societies

Acclimatisation societies existed mainly during the colonial era; their aim was to move species around the world. The first was formed in Paris in 1854. In 1860, an acclimatisation society was formed in London and a year later Peafowl, Pheasants, swans, Starlings and Linnets had been introduced to Australia. The Acclimatisation Society of Victoria, Australia, was formed in 1861.

The Australian colonies were considered to have ‘impoverished’ faunas that could be improved by introducing species to recreate the fauna and flora of the colonists’ homelands. Skylarks, Goldfinches, Pheasants, House Sparrows, thrushes, Mallards, Brown Trout, Cane Toads, Cashmere Goats, Alpacas, deer, Brown Hares and many other species were introduced to Australia. Foxes were introduced for hunting in the 1830s and 1840s; there are now over six million of them, and they have caused the extinction of several native Australian species. European Rabbits were introduced to Australia as food and became widespread in the 1850s. They were successfully introduced in New Zealand in the 1830s, but by 1876 the Rabbit Nuisance Act had been passed, showing that the devastation they caused had been understood. They munched away and multiplied, causing the loss of many plant species, and soil washed away in areas that had been overgrazed by Rabbits. Stoats, later introduced to control Rabbits and Brown Hares, had little effect on the target species and are now a major threat to the native birds of New Zealand!

To understand how commonly humans have moved species, just think about how many familiar animals are actually not native to the British Isles: Grey Squirrels are from the eastern USA, Rabbits are from Spain and Portugal, Fallow Deer are from southern Europe, Little Owls are from mainland Europe, and Pheasants are from Asia.

We now understand the devastation that can be caused to ecosystems by the introduction of non-native plant and animal species. Such species are often invasive (harmful in their new environment): they may carry diseases, outcompete native species, or prey upon them. There are almost 2,000 invasive non-native species in Great Britain. Acclimatisation turned out to be a big mistake, and thankfully societies devoted to the introduction of species to new areas have had their day. In fact, already about 20 years after the peak popularity of acclimatisation, most of the societies had folded, and those remaining were managing zoos and botanical gardens.

The Mountain Hares

A Mountain Hare in its winter coat, almost invisible against the snow.

The Mountain Hare (Lepus timidus) has a body shape similar to the Brown Hare. The two species are so closely related that they have been assigned to the same genus, Lepus. The Mountain Hare, too, has longer hind legs than front legs, a fast galloping gait, long ears and does not burrow, though occasionally leverets make and use shallow burrows. It is mostly solitary, avoids predators by moving fast, and is crepuscular or nocturnal. It is tougher than the Brown Hare – adapted for northerly, mountainous and polar areas – and has slightly longer back feet with thick fur and spreading toes for moving on snow. Its face is more convex than the Brown Hare’s, its ears lack a white patch, and its tail is all white.

The Mountain Hare moults two or three times each year (three times in Scotland: February–May, white to brown; June–September, brown to brown; October–February, brown to white). Its summer coat is brown with blue-grey underfur, but in winter it may remain brown, turn white or partly white, or turn blue-grey. Understandably it is also called the Blue Hare, Tundra Hare, Variable or Varying Hare, White Hare, Snow Hare or Alpine Hare. Black, white and sandy-coloured forms of the Mountain Hare are possible but very rare.

Irish hares on a rainy golf course in Straffan, County Kildare, Ireland. Most Irish Hares remain brown all year round.

The Mountain Hare in Scotland (subspecies Lepus timidus scoticus) is similar to the 13 subspecies found in the rest of Europe: nearly all individuals turn white in winter. The Irish Hare (subspecies Lepus timidus hibernicus) is more distinct from other European subspecies and may prove to be a separate species. Irish Hares often remain reddish brown all year, though some individuals turn partly white in winter (white fur is usually on the rump, flanks and legs; the back and head remain brown).

Range and habitats

The Mountain Hare is found throughout Eurasia, from Norway to Japan, with a stronghold in Russia, Scandinavia and the Baltic States. Further around the globe, it is replaced by two closely related species: the Alaskan or Tundra Hare (Lepus othus) in Alaska, and the Arctic Hare or Polar Rabbit (Lepus arcticus) in Greenland and the Canadian Arctic. Some taxonomists believe that the Mountain Hare, Alaskan Hare and Arctic Hare are the same species.

The Mountain Hares in Ireland, Scotland and the Alps are populations that have survived there since after the last ice age and are now separated from the main population. Other isolated populations exist in Hokkaido (Japan), the Kurile Islands and Sakhalin (Russia). The populations in southern Scotland, some Scottish islands, the Faroe Islands (Denmark), the Isle of Man and the Peak District (UK) were all introduced by humans, mainly in the 19th century. In the Isle of Man and the Peak District, Brown Hares are more common on farmland and Mountain Hares are more common on heather moorland. Irish Hares were introduced to south-western Scotland, and Scottish Mountain Hares were introduced to Ireland and to the Isle of Man. So, as with the Brown Hare, the locations where Mountain Hares are found today are a result of intervention by humans over many decades, as well as a result of natural processes.

A Scottish Mountain Hare in its favourite habitat, heather moorland.

Numbers of Mountain Hares in most areas are stable, and the species is classed as Least Concern by the IUCN (not threatened, vulnerable or endangered). However, numbers have fluctuated in northern Europe and declined in the Alps. Sometimes parasites, predation or starvation cause sudden crashes in the population. Declines have occurred in Russia, and in southern Sweden the Mountain Hare has become locally extinct where the Brown Hare has invaded, habitats have changed, or snow cover has been reduced due to climate change. Competition with the Brown Hare also occurs in Northern Ireland, where historical records of the numbers of Irish Hares shot (game bag data) suggest that numbers are declining.

Mountain Hare world distribution map, showing the subspecies found in Ireland and in Scotland separately, and all 13 other subspecies together. The arrow indicates a small introduced population in the Peak District

Mountain Hares use forms to provide shelter during the day.

The Mountain Hare mostly inhabits mixed forest (pine, birch and juniper), clear-felled areas, open glades, swamps and bogs, river valleys, moor, tundra (a habitat in which small trees are few and far between, moss and heath grows, and the ground is often permanently frozen), and taiga (northern coniferous forests), up to the elevational limit of vegetation (the ‘tree line’). In Scotland heather moorland, forests and pasture are the preferred habitats. In Scotland, Mountain Hares make their forms in heather, snow or peat; even these shallow depressions shelter Mountain Hares effectively from the wind. Some forms are used for many years.

Irish Hares are found in a wide variety of habitats, from the coast where they sometimes eat seaweed, to cereal fields, grassland and the tops of mountains, though they are most common in agricultural grasslands. This means that, in parts of Ireland, Irish Hares and Brown Hares live in the same habitats and compete for food. Mountain Hares feed on many different plants, including grasses, sedges, mosses, trees and shrubs, as well as lichens, but heather is their staple diet in Scotland.

Hares and rabbits

Scottish Mountain Hare in summer, in its favourite habitat, heather moorland.

The species of hare this book focusses on are closely related: they belong to the genus Lepus and have similar biology, appearance and habits. The European Rabbit belongs to a different genus in the same family (Leporidae) and is perhaps more familiar. A comparison between the basic biology of the European Rabbit, the Brown Hare and the Mountain Hare (Scottish and Irish) shows that, though all of them breed ‘like rabbits’, hares have very different social lives – they occupy individual forms and don’t socialise as much as Rabbits, which live in complex colonial burrow systems. Hares are built for speed, and have evolved longer legs, more blood and relatively bigger hearts than Rabbits. Though hares have big ears and excellent hearing, they keep quiet unless threatened, and don’t often use calls to communicate with each other, instead relying on scent and vision. Rabbits use sound more: they thump their feet to raise the alarm.

European Rabbits live in sociable groups in burrows that are often dug into sandy soil.

A Brown Hare skull (left: around 10cm long) and a European Rabbit skull (right; around 7 cm long). The skulls of both species have four incisors in the upper jaw and the bone is delicate in structure so that the skulls are relatively light-weight.

Baby Rabbits are usually born in short burrows that are not connected to the main burrow system. Their mother builds a nest made of grass or moss and lined with her own fur, and once she has given birth she leaves her young together, but sealed up in the burrow most of the time, only returning to feed them. Baby Rabbits are born naked and with their eyes closed, while leverets are born relatively mature and mobile, and can survive without a burrow.

Rabbits are born blind and naked, but Brown Hares are born fully furred and ready for the world.

| Hares and Rabbits compared | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

| Brown or European Hare | Scottish Mountain Hare | Irish Hare (Mountain Hare) | European Rabbit | |

| Scientific name | Lepus europaeus | Lepus timidus scoticus | Lepus timidus hibernicus | Oryctolagus cuniculus |

| Social life | Solitary | Solitary | Solitary | Social, colonial, live in warrens |

| Shelter | Forms | Forms in heather and peat | Forms | Burrows |

| Main food | Herbs, grass, cereals | Heather | Grass | Grass |

| Average adult weight | 3.3–3.7kg (7¼–8⅛lb) | 2.6–2.9kg (5¾–6⅓lb) | 3.2–3.6kg (7–8lb) | 1.2–2kg (2⅔–4⅓lb) |

| Body length | 55cm (22in) | 50cm (20in) | 55cm (22in) | Up to 40cm (16in) |

| Ear length | 10cm (4in) | 7cm (2¾in) | 7.5cm (3in) | 6.5–7.5cm (2½–3in) |

| Hind foot length | 14.5cm (5¾in) | 14cm (5½in) | 15.5cm (2⅛in) | 7.5–10cm (3–4in) |

| Top of tail | Black | White | White | Black |

| Colour | Reddish brown, grizzled | Sandy or greyish brown, usually white in winter | Sandy or greyish brown | Greyish brown, variable |

| Gestation period | 41–42 days | 50 days | 49 days | 30 days |

| Young per female per year | Around 10 | Around 6 | Unknown | 10 to >30 |

| Young (at birth) | Furry and ready to run or hide, eyes open | Furry and ready to run or hide, eyes open | Furry and ready to run or hide, eyes open | Naked and not really mobile, eyes closed |

| Lifespan | 2–3 years, occasionally up to 12 years | 3–4 years, occasionally up to 18 years | 3–4 years | Up to 2 years |