The Arctic Hare or Polar Rabbit (Lepus arcticus) is closely related to the Mountain Hare. This one, in Greenland, is standing on its hind legs to get a better view.

The Arctic Hare or Polar Rabbit (Lepus arcticus) is closely related to the Mountain Hare. This one, in Greenland, is standing on its hind legs to get a better view.

Relatives Around the World

Hares, rabbits, and pikas all belong to the lagomorphs: four-legged, medium-sized mammals that biologists define by special features of their teeth. These close relatives are found on every continent except Antarctica, in many different habitats, including steppe, desert, forest, grassland, moor, scrub, coastal areas, mountains, agricultural land and parks. Lagomorphs are almost entirely herbivorous, unlike their closest relatives among the mammals, the rodents. In common with many rodents, lagomorphs are attractive prey items for lots of predators, and so they have mostly evolved to be experts at watching for danger, avoiding detection, running and hiding.

How we classify living things

Our ancestors would have been familiar with the animals and plants around them, and surely named them, but there were few attempts to standardise the names until Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus started his life’s work on taxonomy, the classification of living things. Along with thousands of other species of animal and plant, he described the Mountain Hare, and named it Lepus timidus, in 1758. Today, living things are classified into kingdoms, phyla, classes, orders, families, genera and species, though the classification is constantly being changed due to new discoveries. The names of genera and species are italicised and form the scientific name of each species as proposed by Linnaeus. Scientific names are useful to avoid any confusion about a species, particularly between scientists from different countries. At international conferences, biologists usually use scientific names to refer to their study species.

Carl Linnaeus, the father of taxonomy.

The three closely related groups of lagomorphs differ greatly in size: with a few exceptions, pikas are tiny, weighing approximately 75–290g (2⅔–10oz), rabbits and cottontails are medium-sized (1–4kg; 2¼–8¾lb), and hares are bigger (2–5kg; 4⅓–11lb). Of the 87 lagomorph species that have been classified by the IUCN, 18 (three pikas, five hares and 10 rabbits) are considered to be Vulnerable, Endangered or Critically Endangered. Confusingly, some rabbits have common names including the word ‘hare’ (the Hispid Hare is really a rabbit), and some hares have common names including the word ‘rabbit’ (the Polar Rabbit and all jackrabbits are hares). The muddle exists only when common rather than scientific names are used – all members of the genus Lepus, and only those 32 species, are hares.

| Scientific classification of hares | ||

| Kingdom | Animalia (animals) |  |

| Phylum | Chordata (animals with a nerve cord) | |

| Class | Mammalia (mammals; animals that feed their young with milk) | |

| Order | Lagomorpha (approximately 91 species of rabbit, hare and pika) | |

| Family | Leporidae (rabbits, cottontails – around 29 species; and hares – 32 species; the other lagomorph family Ochotonidae contains the pikas, around 30 species) | |

| Genus | Lepus (hares and jackrabbits) | |

| Species | timidus (common name: Mountain Hare) | europaeus (common name: Brown or European Hare; above) |

| Subspecies | scoticus (Scotland) hibernicus (Ireland) plus around 13 others | occidentalis (England) plus around 15 others |

A confusing local family

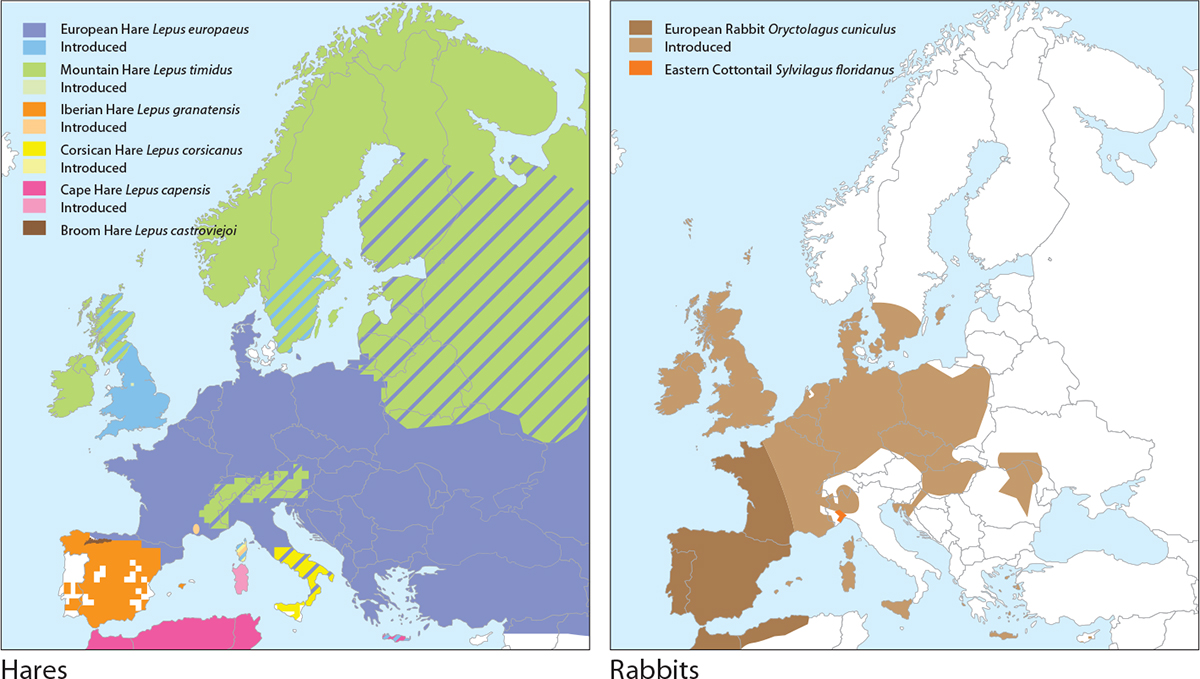

Six species of hare are found in Europe: the Corsican Hare and Broom Hare occupy small and separate ranges, whereas the Iberian Hare, the Brown Hare and the Mountain Hare have much wider ranges that overlap in some places. European Rabbits are also common and widespread in much of Europe. The hares found on Sardinia are believed to be introduced Cape Hares (Lepus capensis; also found in Africa, Arabia and northern India), though they may actually be Iberian Hares.

The Corsican Hare, Broom Hare, Cape Hare and Iberian Hare were all, at times, considered to be subspecies of the Brown Hare, and all look similar. The Corsican Hare and Broom Hare may be the same species, and some taxonomists believe that the Brown Hare is a subspecies of the Cape Hare. In fact, all the hare species in Europe can probably hybridise. It is confusing, and more research on the relationships between the hares in Europe is needed.

Distributions of hares and rabbits in Europe overlap in most areas. The rabbits in the south-western Iberian Peninsula may belong to a different species, and it is unknown whether the Brown Hare is introduced or native in Britain.

The Corsican Hare (Lepus corsicanus) is found south of the Abruzzo Mountains in Italy, on Sicily and in small numbers on Corsica, where it was introduced by humans, probably before 1400. It inhabits maquis (evergreen) shrubland, grassland, cultivated areas and dunes. The Brown Hare and the Iberian Hare were introduced to Corsica much more recently, in their thousands, and all three species hybridise there. The Corsican Hare’s head and body length is 44–61cm (17–24in), body weight is 1.8–3.8kg (4–8⅓lb) and ear length is 9–13cm (3½–5⅛in) so it is smaller than the Brown Hare. The Corsican Hare is classed as Vulnerable by the IUCN; it is threatened by habitat loss, illegal hunting and competition with European Rabbits and introduced hares.

The Cape Hare: introduced to Sardinia, naturally found in Africa, Arabia and northern India. In its native range, it is predated upon by the Cheetah, the only predator that can outrun the Cape Hare.

The Corsican Hare was introduced to Corsica by humans, and a few are still there, but its stronghold is in southern Italy and on Sicily. It is considered Vulnerable by the IUCN.

Without an expert guide, it would be almost impossible to see a Broom Hare (Lepus castroviejoi). This species is found only in the Cantabrian Mountains in northern Spain, in a region about 230km (143 miles) from east to west and 25–40km (16–25 miles) from north to south. It lives at elevations up to 2,000m (6,560ft), though it moves down the mountains into warmer areas in winter. It is found in broom and heather heathland, and in clearings in oak and beech forests. The Broom Hare was not classified as separate from the Brown Hare until 1976, and little is known about its habits. It is classed as Vulnerable by the IUCN and the main threat to the species is unsustainable hunting of its small population.

The Iberian Hare has a bright white underside that extends forward around the front legs.

The Broom Hare, found only in the Cantabrian Mountains in northern Spain, is threatened by hunting.

The Iberian Hare or Granada Hare (Lepus granatensis) is found in the southern Iberian Peninsula, on Mallorca and in southern France, so it overlaps in places with the Brown Hare and with the Broom Hare. Its fur colour changes abruptly from grizzled brown to white on its sides, giving it a brighter appearance than the Brown Hare. It breeds all year round and occupies diverse habitats including arable land, mountainous forests and sand dunes; its numbers are believed to be stable.

Hares of snow, desert and water

Left: This Snowshoe Hare is moulting. Its large feet allow it to walk on snow without sinking into it.

Right: Despite its winter coat camouflaging it in the snow, this Snowshoe Hare has been caught by a Canadian Lynx.

Lagomorphs are found in some surprising places. With special adaptations, they can thrive in cold, arid, and wet places. Large snow-shoe like feet have evolved in the Snowshoe Hare or Snowshoe Rabbit (Lepus americanus), the smallest species of hare (900g to 2kg/ 2–4⅓lb); it lives in the forests of northern North America. It is similar in size to a European Rabbit and has short ears to conserve energy by minimising heat loss. Its large, furry hind feet allow it to run on top of snow without sinking into it. It has extremely thick, insulating fur, which is white in winter (except for its black ear tips) and brown in summer. Climate change is likely to cause problems for this species: as snowfall decreases, the white winter coat will be less effective as camouflage. The Canadian Lynx, Coyote and Fisher are its main predators. Populations of Lynx and Snowshoe Hares follow predictable patterns – regular climatic changes cause rises and falls in the Snowshoe Hare population, which are followed two years later by rises and falls in the Lynx population. The population cycles last 8–11 years, and were first noticed over 200 years ago by trappers working in the fur trade.

An Endangered Tehuantepec Jackrabbit rests in its form during the day. It has large ears, and a characteristic black stripe (just visible) running from the base of its ear towards its back.

The Tehuantepec Jackrabbit (Lepus flavigularis) is the rarest hare species. It is classed as Endangered by the IUCN and threatened by hunting and habitat loss. Fewer than 1,000 Tehuantepec Jackrabbits still survive today. It has the most southerly range of any hare species in North America, occurring in southern Mexico, around the Gulf of Tehuantepec. It inhabits grassland with scattered shrubs and trees, shrub forest and coastal grassy dunes within 4–5km (2½–3⅛ miles) of the shores of saltwater lagoons, and is not found at elevations over 500m (1,640ft).

Most hares need a regular source of water, but the Antelope Jackrabbit (Lepus alleni), found from the desert plains of south-central Arizona to the west coast of Mexico, prefers extremely dry desert scrub and does not need to drink water (it gets water mostly from the grasses, cacti and other plants it eats). It is large (3–4.5kg/6⅔–10lb), and has enormous ears (over 10cm/4in wide and 21cm/8¼in long) with very sparse hair. The ears are used to regulate body temperature – when it wants to cool down, the hare pumps blood into them. Females sometimes line their forms with fur and grass before they give birth. This species runs fast, and can leap several metres into the air. It sometimes stands on its hind feet; this allows it to feed on tall plants and to hop like a kangaroo for a few strides at a time. When running away from danger, the Antelope Jackrabbit displays a large white patch on its rump, which looks like the white rump of a Pronghorn Antelope, and gives the Antelope Jackrabbit its common name.

The Antelope Jackrabbit is perfectly adapted to life in the desert. It uses its huge ears, which contain many blood vessels, to cool itself down.

Most mammals can swim if they need to, but only one lagomorph makes a habit of swimming. The Swamp Rabbit (Sylvilagus aquaticus) is semi-aquatic. It is found in swamps and wetlands in south-central USA, and weighs 2–3kg (4⅓–6⅔lb). It swims to avoid predators, and may also lie still in the water, hidden by floating twigs and plants, with only its nose visible. It is hunted by humans, American Alligators and domestic dogs. It does not make burrows, but uses hare-like forms or nests.

The Swamp Rabbit, the only lagomorph that regularly swims, has the American Alligator as one of its predators.

From superabundant to extremely rare

The European Rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) probably has the widest range of the lagomorphs because it has been introduced in many places and is domesticated. It is a pest species outside its natural range (Spain, Portugal and north-western Africa), but within this range it is classed as Near Threatened by the IUCN. The rabbits in the south-western Iberian Peninsula may actually belong to a separate species, which has yet to be formally described. European Rabbits live in colonies and create large burrow systems (warrens) to avoid predation. Rabbits have aggressive encounters to establish a hierarchy – dominant males are able to mate with many females and so father more young. The European Rabbit is a key prey species that is critical for the conservation of species such as the Iberian Lynx and Imperial Eagle. Myxomatosis and Rabbit Haemorrhagic Disease have caused huge declines in Rabbit numbers, and Rabbits are also threatened by unsustainable hunting in their natural range.

The Riverine Rabbit (Bunolagus monticularis) is one of the rarest species of mammal: there are only about 250 adults, numbers are decreasing, and it is classed as Critically Endangered by the IUCN. It is found only in the central and southern parts of the Karoo Desert, in Cape Province, South Africa, in river basins and shrubland. It has a clear black stripe running from the corner of its mouth over its cheek, cream fur on its belly and throat, and a white ring around the eye; it weighs 1.4–2kg (3⅛–4⅓lb) and creates burrows. Female Riverine Rabbits produce only one young per year.

A young European Rabbit. This species has become established in many places around the world.

A Riverine Rabbit caught by an automated camera used as a survey tool by the Endangered Wildlife Trust in South Africa. The black stripe on the cheek and the cream fur on the throat are key identification features.

The striking Annamite Striped Rabbit (Nesolagus timminsi) inhabits evergreen rainforests in the Annamite Mountains on the border between Vietnam and Laos. It has seven clear black or dark brown stripes on its body and a reddish rump. It was first described in 1995 and first captured by biologists in 2015. Numbers are believed to be decreasing: the Annamite Striped Rabbit is hunted, and its habitat is threatened by logging and agricultural practices. It has a very restricted range and is almost certainly extremely rare and threatened.

An Annamite Striped Rabbit caught on an automated camera used by researchers in the Quang Nam Saola Nature Reserve, Vietnam. The eyeshine that makes hares stand out in spotlight counts is visible here.

Tiny rabbits in special places

Hares and rabbits come in a range of sizes. At one end of the scale, we have the Brown Hare and the Arctic Hare, which weigh up to 5kg (11lb). At the other end, the smallest member of the Leporidae family is the Pygmy Rabbit (Brachylagus idahoensis), which is 25–29cm (9¾–11in) long and weighs just 300–400g (11–14oz). This tiny rabbit would easily fit in the palm of your hand. The Pygmy Rabbit is found in the parts of the western USA where its food plant, Big Sagebrush, occurs. It is the only native rabbit species in North America that digs. Most hares and rabbits are silent unless they are in extreme danger, but Pygmy Rabbits squeal, squeak and chuckle. There can’t be much meat on a Pygmy Rabbit, but they are hunted by humans as well as by weasels, American Badgers, Coyotes, Bobcats, Red Foxes, and by birds of prey, both during the day (falcons) and at night (owls).

This is the smallest member of the Leporidae family, the Pygmy Rabbit. Fourteen of these tiny rabbits weigh as much as one Brown Hare.

The Endangered Volcano Rabbit (Romerolagus diazi) is also very tiny (27–36cm/11–14in, 400–600g/14–21oz). This species is restricted to four volcanoes in the central Transverse Neovolcanic Belt in Mexico, and lives in a specific subalpine habitat containing bunchgrass (grass that grows in tussocks, rather than as a flat ‘lawn’), and in some pine forests. It has very short ears and legs, and a minuscule tail. Only a few thousand individuals survive, their populations are fragmented and they are hunted for food by humans. It is also threatened by climate change, livestock grazing, agriculture, property development, logging, bunchgrass harvesting and forest fires. The future is very uncertain for this endangered species, especially because it can live only in a very specific subalpine habitat. Protection of the remaining individuals is urgently needed.

The Volcano Rabbit is extremely tiny and also very rare. It is found only in a small part of Mexico.

The pikas

Pikas, also known as mouse-hares, rock-rabbits, hay-makers and whistling hares, are much smaller than the Leporidae (rabbits, cottontails and hares). The 30 or so species, all in the genus Ochotona, look like rodents because they lack the long ears of rabbits and hares. But they are better described as rabbits with egg-shaped bodies, short ears and apparently no tail (they actually have a relatively long tail, but it is never visible). They inhabit cold places, mostly mountains in central Asia and North America. Around 23 species are found in Asia.

Most pikas are more active during the day than at night. Pikas store food for the winter in ‘hay piles’, usually under rocks, which they defend aggressively against theft. The thieves are not only members of their own species; hay piles are also eaten by other hungry herbivores such as domestic cows and horses, Reindeer, goats, hares, marmots and voles. Mongolian herdsmen prefer to graze their animals where there are pikas because of the extra food provided by hay piles.

The American Pika or Little Chief Hare stores food for the winter in ‘hay piles’ under rocks.

Pikas are much noisier than rabbits and hares: they whistle, squeak and ‘sing’ to communicate, and groups have distinct dialects. Some solitary, territorial species live in rocky screes; other more social species live in burrow systems in high-elevation steppe habitat. Pikas are important prey species, and in Russia they were killed in their thousands every year for their skins until the 1950s. The fur was used to make felt.

The cute Ili Pika is found only in northwest China. Its numbers are declining and it is classed as Endangered.

One of the largest but least-known species, the Endangered Ili Pika (Ochotona iliensis) was discovered in 1983 and has rarely been seen since. In the 1990s, there were only an estimated 2,000 individuals, and declines have occurred since then. The Ili Pika lives only in rocky screes on high cliff faces in the Tian Shan Mountains in Xinjiang, China. It weighs about 250g (8¾oz) and has brightly patterned, longish fur and rusty-red spots on its head; some people think it looks like a teddy bear. It is rarer, and arguably cuter, than the Giant Panda.

The American Pika (Ochotona princeps), also called the Little Chief Hare (the name used by the Chipewyan people), is found in high-elevation boulder fields in the mountains of western North America. It weighs 120–170g (4¼–6oz) and its body is 16–22cm (6⅓–8⅓in) long; it is greyish brown with white margins to its small, round ears, and long whiskers (4–8cm/1½–3⅛in). American Pikas often live under piles of broken rocks. They can only live in high, cool mountain regions and cannot tolerate high temperatures, so they may provide an early warning system to detect the effects of global warming – if numbers of American Pikas decline, temperatures may be increasing.