An offering of a gazelle and a hare shown on a painting from the Tomb of Ounsou in West Thebes, Egypt, c. 1450 BC.

An offering of a gazelle and a hare shown on a painting from the Tomb of Ounsou in West Thebes, Egypt, c. 1450 BC.

Humans and Hares

Humans have interacted with hares for thousands of years, and it’s clear that hares fascinate people. Historically an important source of food for many communities, wild hare is still enjoyed by many people today. Hares have also been used by humans in field sports, often to the hares’ distress and detriment, and some people have, perhaps misguidedly, kept these beautiful wild animals as pets.

Hare products

Luckily for hares, they are hardly used in the fur industry, though hare skins can be used to make garments and their fur can be made into felt. Rabbit skins are used much more, and many Rabbits are bred only for their skins. Hairs from the ears, face and body of Brown Hares (and other species) are used to make fishing flies called ‘hare’s ears’, which resemble the larvae of aquatic insects and are used to attract trout and other fish.

Most hares deliberately killed by humans are shot and eaten. Of the 32 hare species worldwide, the Brown Hare is one of the top three in terms of sheer numbers killed by humans. Around 70 million Brown Hares were exported from South America to Europe each year in the 1980s, and today over five million are killed each year in Europe. In Britain alone, hundreds of thousands of our hares are shot each year.

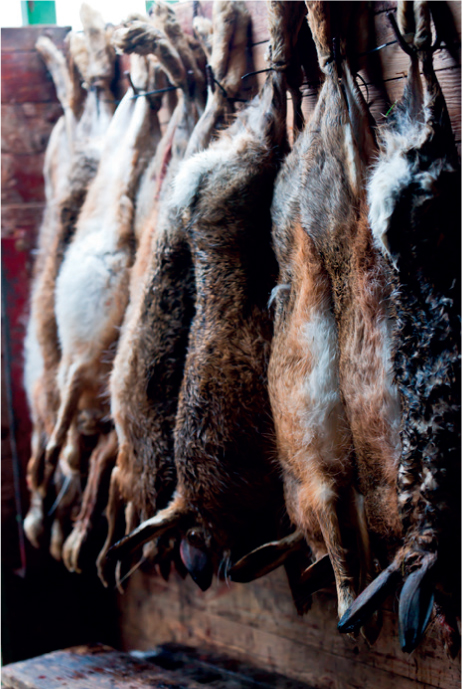

Hunted Brown Hares in a game larder, ready to be used as food.

It is easy to understand the appeal of hare as a food source for humans. One hare can provide a substantial amount of meat, enough to feed perhaps eight people but, before you could cook and eat it, first you had to catch one. ‘First catch your hare’ is often claimed to be the first step in a recipe from Hannah Glasse’s book The Art of Cookery made Plain and Easy, published in 1747, but in fact she didn’t use that phrase. Mrs Glasse did warn her readers not to try to cook a hare with the skin on: ‘Take your Hare when it is cas’d [skinned], and make a pudding…’. Isabella Beeton, in her 1861 book Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management, offered her readers tips on how to choose a young hare: ‘The ears of a young hare easily tear, and it has a narrow cleft in the lip; whilst its claws are both smooth and sharp.’

To make jugged hare, the meat is marinated in wine and cooked very slowly.

Hare meat is lean, dark and rich in flavour, so slow stewing is a good way to cook it, though young hares can also be roasted. A recipe for hare that has survived from Roman Britain involves stuffing the hare with pine kernels, almonds, spices, eggs and giblets, roasting it, and serving it with a sauce made from onions, dates, herbs and spices. Jugged hare, a traditional dish dating back to 17th century England (similar to the French civet de lièvre recipe) involves marinating hare in red wine with Juniper berries and cooking it slowly in a jug standing in a pan of water.

In Germany, hasenpfeffer is a traditional hare stew made from hare braised with onions, wine, vinegar, pepper and other spices. Similar recipes including paprika, sweet peppers and sometimes sour cream come from further east. Hare meat often features in game terrine or pâté, and the loin and back legs can be eaten fried, or made into a ragu and eaten with pasta (usually pappardelle). The modern trend is towards serving hare meat simply seasoned and grilled, to allow its unique flavour to be enjoyed.

It is of course desirable, though currently very difficult, to ensure that any hare we eat comes from a sustainably hunted population. Almost all countries in continental Europe, as well as Scotland, have a closed season for the hare, which at least ensures that they are not hunted at the start of the breeding season as they often are in England (see here). If a closed season is introduced in England, it will benefit the welfare of hares and go a long way towards ensuring that any hunting is sustainable, so that wild hares can thrive for many years to come.

The ‘sport’ of hare hunting

Hares hunted for sport, with the assistance of hawks, falcons or dogs, are sometimes eaten by the humans or the dogs. Poachers take hares illegally, without the permission of the landowner, probably mostly by lamping and shooting at night and with the help of lurchers (usually crosses between the sight hounds used for coursing and other working dogs). The effect of poaching on hare populations is unknown. Hares have also been taken by snaring – in nets placed across runs or gateways – by throwing hunting-sticks at their legs to make them tumble, by carefully aimed stones and by pitfall trapping.

There are two other ways in which dogs hunt hares. Hounds tracking hares by scent, mostly beagles or harriers, work in packs with humans following on foot or horseback. The dogs can take their time to find a hare and don’t need to outrun it. Eventually the hare tires and they are able to catch and eat it.

Hare hunting with a falcon, from an image published in Paris in 1864.

Beagle packs were used to hunt hares in England until 2005.

Greyhound racing, where the dogs follow a lure in the form of a mechanical ‘hare’, developed from hare coursing.

Hounds tracking hares by sight (coursing), often greyhounds or other sight hounds, have to be fast enough to outrun their quarry. Until it became illegal in 2002 in Scotland and in 2005 in England, coursing was organised as competitions between pairs of dogs and points were awarded for turning and killing the hare. It was practised as walked-up coursing, where a line of beaters would flush a hare from its form and two dogs were released to catch it; or as driven coursing, where hares were caught beforehand and later released for pairs of dogs to chase in front of spectators on a fenced course (as in the Waterloo Cup), with the hare given a head start of up to 100m (328ft). Coursing has an ancient history of more than 3,000 years, and if Brown Hares were introduced to Britain, they were probably introduced for the purpose of coursing. It is practised in many parts of the world, for example, in the USA, sight hounds are used to hunt jackrabbits (hares). Greyhound racing, using a fake mechanical ‘hare’ or lure, developed from coursing but is cruelty-free (for hares, at least).

Lady Florence Dixie, who called hare coursing ‘torture’.

Hunting hares with dogs is highly controversial and has been considered by some to be cruel and unnecessary for hundreds of years. In 1516, Thomas More wrote in Utopia: ‘Thou shouldst rather be moved with pity to see a silly innocent hare murdered of a dog, the weak of the stronger, the fearful of the fierce, the innocent of the cruel and unmerciful. Therefore, all this exercise of hunting is a thing unworthy to be used of free men.’ In 1892, British feminist and writer Lady Florence Dixie called hare coursing an ‘aggravated form of torture’.

Hare coursing – two sight hounds compete to turn and kill the hare.

The League Against Cruel Sports was founded in 1924 and its aims included banning hare hunting and coursing. In England, the House of Commons voted to ban hare coursing in 1969 and 1975, but neither ban passed the House of Lords to become law. In 2002, the Scottish Parliament banned hare coursing in Scotland, and in 2004 the British Parliament passed the Hunting Act, which banned hare coursing and other forms of hunting with dogs from February 2005. The Waterloo Cup, which started in 1836, took place for the last time in 2005. It was the end of an era, but a victory for hare welfare.

Coursing. A Brown Hare runs for its life, while a sight hound with a white collar competes against another with a red collar (not shown).

Hares as pets

Some people have kept hares as pets, though, like most wild animals, they are not particularly suited to it. Hares prefer to live in wide open spaces and so keeping hares confined in any way is unnatural; even in captive breeding centres, hares never really become tame. Sometimes people who come across leverets alone believe – rightly or wrongly – they have been orphaned and hand-rear them in order to rehabilitate and release them. This is controversial – people may consider it kind or interesting to ‘save’ an individual animal, but it is perhaps better for an orphaned leveret to remain in its natural habitat and part of the food chain as prey for a Fox.

The Belgian hare is a domestic rabbit breed that looks rather hare-like. If you love hares and wish you could have one as a pet, a Belgian hare is the best bet. These rabbits have been bred in captivity over many generations and are easier to care for and more suited to captivity than wild animals are.

If they are released back into the wild, hand-reared hares like this one sadly have little chance of survival.

A young Brown Hare being hand-fed on formula.

The Belgian hare, a domestic rabbit breed, looks like a hare and makes a good pet.