Appendix G. Django-Rest-Framework

Having “rolled our own” REST API in the last appendix, it’s time to take a look at Django-Rest-Framework, which is a go-to choice for many Python/Django developers building APIs. Just as Django aims to give you all the basic tools that you’ll need to build a database-driven website (an ORM, templates, and so on), so DRF aims to give you all the tools you need to build an API, and thus avoid you having to write boilerplate code over and over again.

Writing this appendix, one of the main things I struggled with was getting the exact same API that I’d just implemented manually to be replicated by DRF. Getting the same URL layout and the same JSON data structures I’d defined proved to be quite a challenge, and I felt like I was fighting the framework.

That’s always a warning sign. The people who built Django-Rest-Framework are a lot smarter than I am, and they’ve seen a lot more REST APIs than I have, and if they’re opinionated about the way that things “should” look, then maybe my time would be better spent seeing if I can adapt and work with their view of the world, rather than forcing my own preconceptions onto it.

“Don’t fight the framework” is one of the great pieces of advice I’ve heard. Either go with the flow, or perhaps reassess whether you want to be using a framework at all.

We’ll work from the API we had at the end of the last appendix, and see if we can rewrite it to use DRF.

Installation

A quick pip install gets us DRF. I’m just using the latest version, which

was 3.5.4 at the time of writing:

$ pip install djangorestframework

And we add rest_framework to INSTALLED_APPS in settings.py:

superlists/settings.py

INSTALLED_APPS=[#'django.contrib.admin','django.contrib.auth','django.contrib.contenttypes','django.contrib.sessions','django.contrib.messages','django.contrib.staticfiles','lists','accounts','functional_tests','rest_framework',]

Serializers (Well, ModelSerializers, Really)

The Django-Rest-Framework tutorial is a pretty good resource to learn DRF. The first thing you’ll come across is serializers, and specifically in our case, “ModelSerializers”. They are DRF’s way of converting from Django database models to JSON (or possibly other formats) that you can send over the wire:

lists/api.py (ch37l003)

fromlists.modelsimportList,Item[...]fromrest_frameworkimportrouters,serializers,viewsetsclassItemSerializer(serializers.ModelSerializer):classMeta:model=Itemfields=('id','text')classListSerializer(serializers.ModelSerializer):items=ItemSerializer(many=True,source='item_set')classMeta:model=Listfields=('id','items',)

Viewsets (Well, ModelViewsets, Really) and Routers

A ModelViewSet is DRF’s way of defining all the different ways you can interact

with the objects for a particular model via your API. Once you tell it which

models you’re interested in (via the queryset attribute) and how to serialize

them (serializer_class), it will then do the rest—automatically building

views for you that will let you list, retrieve, update, and even delete objects.

Here’s all we need to do for a ViewSet that’ll be able to retrieve items for a particular list:

lists/api.py (ch37l004)

classListViewSet(viewsets.ModelViewSet):queryset=List.objects.all()serializer_class=ListSerializerrouter=routers.SimpleRouter()router.register(r'lists',ListViewSet)

A router is DRF’s way of building URL configuration automatically, and mapping them to the functionality provided by the ViewSet.

At this point we can start pointing our urls.py at our new router, bypassing the old API code and seeing how our tests do with the new stuff:

superlists/urls.py (ch37l005)

[...]# from lists.api import urls as api_urlsfromlists.apiimportrouterurlpatterns=[url(r'^$',list_views.home_page,name='home'),url(r'^lists/',include(list_urls)),url(r'^accounts/',include(accounts_urls)),# url(r'^api/', include(api_urls)),url(r'^api/',include(router.urls)),]

That makes loads of our tests fail:

$ python manage.py test lists

[...]

django.urls.exceptions.NoReverseMatch: Reverse for 'api_list' not found.

'api_list' is not a valid view function or pattern name.

[...]

AssertionError: 405 != 400

[...]

AssertionError: {'id': 2, 'items': [{'id': 2, 'text': 'item 1'}, {'id': 3,

'text': 'item 2'}]} != [{'id': 2, 'text': 'item 1'}, {'id': 3, 'text': 'item

2'}]

---------------------------------------------------------------------

Ran 54 tests in 0.243s

FAILED (failures=4, errors=10)

Let’s take a look at those 10 errors first, all saying they cannot reverse

api_list. It’s because the DRF router uses a different naming convention

for URLs than the one we used when we coded it manually. You’ll see from the

tracebacks that they’re happening when we render a template. It’s list.html.

We can fix that in just one place; api_list becomes list-detail:

lists/templates/list.html (ch37l006)

<script>$(document).ready(function(){varurl="{% url 'list-detail' list.id %}";});</script>

That will get us down to just four failures:

$ python manage.py test lists [...] FAIL: test_POSTing_a_new_item (lists.tests.test_api.ListAPITest) [...] FAIL: test_duplicate_items_error (lists.tests.test_api.ListAPITest) [...] FAIL: test_for_invalid_input_returns_error_code (lists.tests.test_api.ListAPITest) [...] FAIL: test_get_returns_items_for_correct_list (lists.tests.test_api.ListAPITest) [...] FAILED (failures=4)

Let’s DONT-ify all the validation tests for now, and save that complexity for later:

lists/tests/test_api.py (ch37l007)

[...]defDONTtest_for_invalid_input_nothing_saved_to_db(self):[...]defDONTtest_for_invalid_input_returns_error_code(self):[...]defDONTtest_duplicate_items_error(self):[...]

And now we have just two failures:

FAIL: test_POSTing_a_new_item (lists.tests.test_api.ListAPITest)

[...]

self.assertEqual(response.status_code, 201)

AssertionError: 405 != 201

[...]

FAIL: test_get_returns_items_for_correct_list

(lists.tests.test_api.ListAPITest)

[...]

AssertionError: {'id': 2, 'items': [{'id': 2, 'text': 'item 1'}, {'id': 3,

'text': 'item 2'}]} != [{'id': 2, 'text': 'item 1'}, {'id': 3, 'text': 'item

2'}]

[...]

FAILED (failures=2)

Let’s take a look at that last one first.

DRF’s default configuration does provide a slightly different data structure to the one we built by hand—doing a GET for a list gives you its ID, and then the list items are inside a key called “items”. That means a slight modification to our unit test, before it gets back to passing:

lists/tests/test_api.py (ch37l008)

@@ -23,10 +23,10 @@ class ListAPITest(TestCase):response = self.client.get(self.base_url.format(our_list.id)) self.assertEqual( json.loads(response.content.decode('utf8')),- [+ {'id': our_list.id, 'items': [{'id': item1.id, 'text': item1.text}, {'id': item2.id, 'text': item2.text},- ]+ ]})

That’s the GET for retrieving list items sorted (and, as we’ll see later, we’ve got a bunch of other stuff for free too). How about adding new ones, using POST?

A Different URL for POST Item

This is the point at which I gave up on fighting the framework and just saw where DRF wanted to take me. Although it’s possible, it’s quite torturous to do a POST to the “lists” ViewSet in order to add an item to a list.

Instead, the simplest thing is to post to an item view, not a list view:

lists/api.py (ch37l009)

classItemViewSet(viewsets.ModelViewSet):serializer_class=ItemSerializerqueryset=Item.objects.all()[...]router.register(r'items',ItemViewSet)

So that means we change the test slightly, moving all the POST tests

out of the

ListAPITest and into a new test class, ItemsAPITest:

lists/tests/test_api.py (ch37l010)

@@-1,3+1,4@@importjson+fromdjango.core.urlresolversimportreversefromdjango.testimportTestCasefromlists.modelsimportList,Item@@-31,9+32,13@@classListAPITest(TestCase):++classItemsAPITest(TestCase):+base_url=reverse('item-list')+deftest_POSTing_a_new_item(self):list_=List.objects.create()response=self.client.post(-self.base_url.format(list_.id),-{'text':'new item'},+self.base_url,+{'list':list_.id,'text':'new item'},)self.assertEqual(response.status_code,201)

That will give us:

django.db.utils.IntegrityError: NOT NULL constraint failed: lists_item.list_id

Until we add the list ID to our serialization of items; otherwise, we don’t know what list it’s for:

lists/api.py (ch37l011)

classItemSerializer(serializers.ModelSerializer):classMeta:model=Itemfields=('id','list','text')

And that causes another small associated test change:

lists/tests/test_api.py (ch37l012)

@@-25,8+25,8@@classListAPITest(TestCase):self.assertEqual(json.loads(response.content.decode('utf8')),{'id':our_list.id,'items':[-{'id':item1.id,'text':item1.text},-{'id':item2.id,'text':item2.text},+{'id':item1.id,'list':our_list.id,'text':item1.text},+{'id':item2.id,'list':our_list.id,'text':item2.text},]})

Adapting the Client Side

Our API no longer returns a flat array of the items in a list. It returns an

object, with a .items attribute that represents the items. That means a

small tweak to our updateItems function:

lists/static/list.js (ch37l013)

@@ -3,8 +3,8 @@ window.Superlists = {};window.Superlists.updateItems = function (url) { $.get(url).done(function (response) { var rows = '';- for (var i=0; i<response.length; i++) {- var item = response[i];+ for (var i=0; i<response.items.length; i++) {+ var item = response.items[i];rows += '\n<tr><td>' + (i+1) + ': ' + item.text + '</td></tr>'; } $('#id_list_table').html(rows);

And because we’re using different URLs for GETing lists and POSTing items,

we tweak the initialize function slightly too. Rather than multiple

arguments, we’ll switch to using a params object containing the required

config:

lists/static/list.js

@@ -11,23 +11,24 @@ window.Superlists.updateItems = function (url) {}); };-window.Superlists.initialize = function (url) {+window.Superlists.initialize = function (params) {$('input[name="text"]').on('keypress', function () { $('.has-error').hide(); });- if (url) {- window.Superlists.updateItems(url);+ if (params) {+ window.Superlists.updateItems(params.listApiUrl);var form = $('#id_item_form'); form.on('submit', function(event) { event.preventDefault();- $.post(url, {+ $.post(params.itemsApiUrl, {+ 'list': params.listId,'text': form.find('input[name="text"]').val(), 'csrfmiddlewaretoken': form.find('input[name="csrfmiddlewaretoken"]').val(), }).done(function () { $('.has-error').hide();- window.Superlists.updateItems(url);+ window.Superlists.updateItems(params.listApiUrl);}).fail(function (xhr) { $('.has-error').show(); if (xhr.responseJSON && xhr.responseJSON.error) {

We reflect that in list.html:

lists/templates/list.html (ch37l014)

$(document).ready(function () {

window.Superlists.initialize({

listApiUrl: "{% url 'list-detail' list.id %}",

itemsApiUrl: "{% url 'item-list' %}",

listId: {{ list.id }},

});

});And that’s actually enough to get the basic FT working again:

$ python manage.py test functional_tests.test_simple_list_creation [...] Ran 2 tests in 15.635s OK

There’s a few more changes to do with error handling, which you can explore in the repo for this appendix if you’re curious.

What Django-Rest-Framework Gives You

You may be wondering what the point of using this framework was.

Configuration Instead of Code

Well, the first advantage is that I’ve transformed my old procedural view function into a more declarative syntax:

lists/api.py

deflist(request,list_id):list_=List.objects.get(id=list_id)ifrequest.method=='POST':form=ExistingListItemForm(for_list=list_,data=request.POST)ifform.is_valid():form.save()returnHttpResponse(status=201)else:returnHttpResponse(json.dumps({'error':form.errors['text'][0]}),content_type='application/json',status=400)item_dicts=[{'id':item.id,'text':item.text}foriteminlist_.item_set.all()]returnHttpResponse(json.dumps(item_dicts),content_type='application/json')

If you compare this to the final DRF version, you’ll notice that we are actually now entirely configured:

lists/api.py

classItemSerializer(serializers.ModelSerializer):text=serializers.CharField(allow_blank=False,error_messages={'blank':EMPTY_ITEM_ERROR})classMeta:model=Itemfields=('id','list','text')validators=[UniqueTogetherValidator(queryset=Item.objects.all(),fields=('list','text'),message=DUPLICATE_ITEM_ERROR)]classListSerializer(serializers.ModelSerializer):items=ItemSerializer(many=True,source='item_set')classMeta:model=Listfields=('id','items',)classListViewSet(viewsets.ModelViewSet):queryset=List.objects.all()serializer_class=ListSerializerclassItemViewSet(viewsets.ModelViewSet):serializer_class=ItemSerializerqueryset=Item.objects.all()router=routers.SimpleRouter()router.register(r'lists',ListViewSet)router.register(r'items',ItemViewSet)

Free Functionality

The second advantage is that, by using DRF’s ModelSerializer, ViewSet, and routers, I’ve actually ended up with a much more extensive API than the one I’d rolled by hand.

-

All the HTTP methods, GET, POST, PUT, PATCH, DELETE, and OPTIONS, now work, out of the box, for all list and items URLs.

-

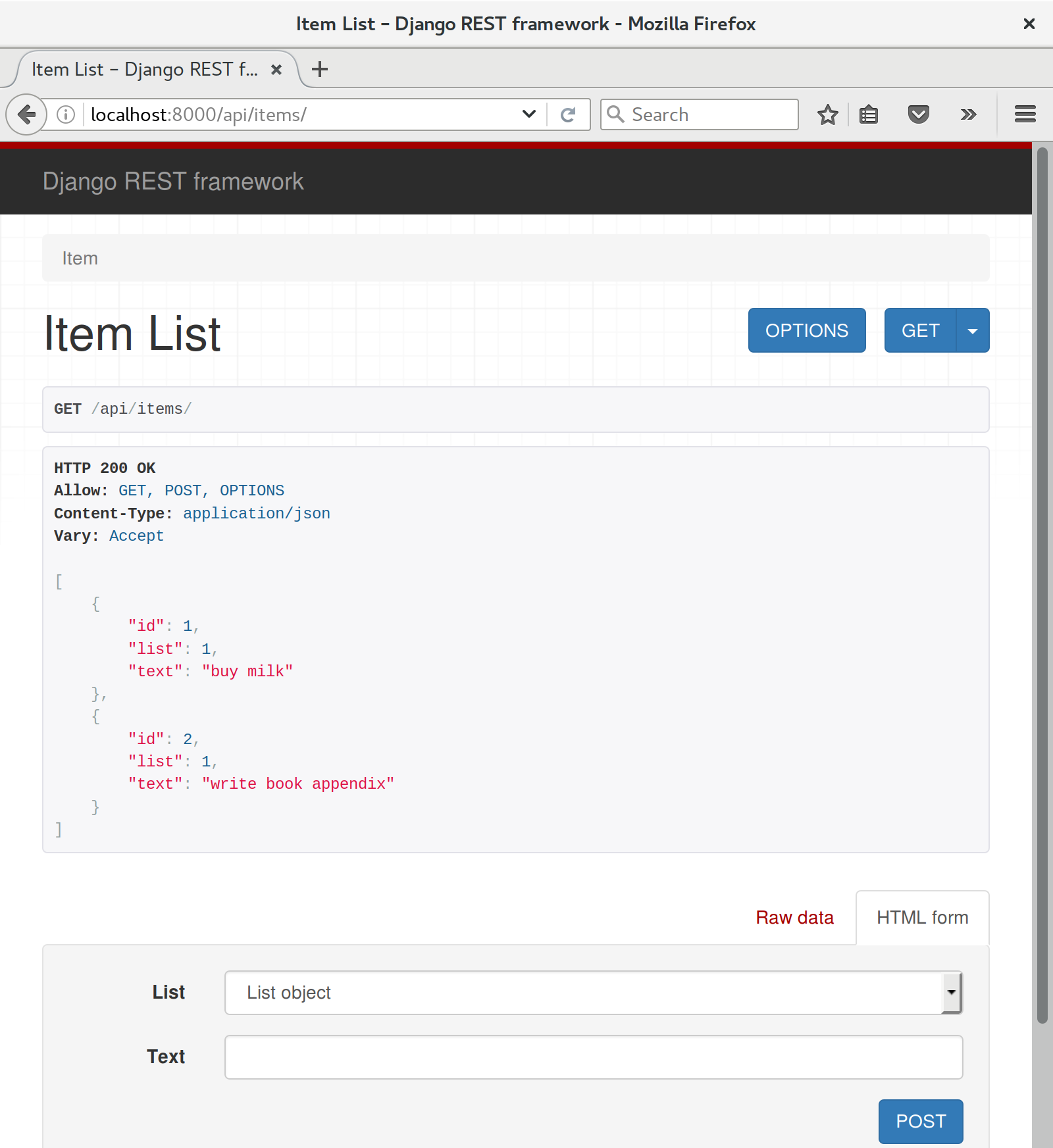

And a browsable/self-documenting version of the API is available at http://localhost:8000/api/lists/ and http://localhost:8000/api/items. (Figure G-1; try it!)

Figure G-1. A free browsable API for your users

There’s more information in the DRF docs, but those are both seriously neat features to be able to offer the end users of your API.

In short, DRF is a great way of generating APIs, almost automatically, based on your existing models structure. If you’re using Django, definitely check it out before you start hand-rolling your own API code.