Welcome to the

Platform Revolution

In October 2007, a tiny item appeared in an online newsletter aimed at industrial designers—men and women who shape the appearance of everything from coffee makers to jumbo jets. It referred to an unusual housing option for professionals who planned to attend the upcoming joint convention of two industrial design organizations, the International Congress of Societies of Industrial Design (ICSID) and the Industrial Designers Society of America (IDSA):

If you’re heading out to the ICSID/IDSA World Congress/Connecting ’07 event in San Francisco next week and have yet to make accommodations, well, consider networking in your jam-jams. That’s right. For “an affordable alternative to hotels in the city,” imagine yourself in a fellow design industry person’s home, fresh awake from a snooze on the ol’ air mattress, chatting about the day’s upcoming events over Pop Tarts and OJ.

The hosts for this “networking in your jam-jams” opportunity were Brian Chesky and Joe Gebbia, budding designers who’d moved to San Francisco only to find they couldn’t afford the rent on the loft they shared. Strapped for cash, they impulsively decided to make air mattresses and their own services as part-time tour guides available to convention attendees. Chesky and Gebbia attracted three weekend guests and made a thousand bucks, which covered the next month’s rent.

Their casual space-sharing experience would launch a revolution in one of the world’s biggest industries.

Chesky and Gebbia recruited a third friend, Nathan Blecharczyk, to help them make affordable room rentals a long-term business. Of course, renting space in their San Francisco loft wouldn’t yield much revenue. So they designed a website that allowed anyone, anywhere, to make a spare sofa or guest room available to travelers. In exchange, the company—now dubbed Air Bed & Breakfast (Airbnb), after the air mattresses in Chesky and Gebbia’s loft—took a slice of the rental fee.

The three partners started out focusing on events for which hotel space was often sold out, scoring their first big hit at the 2008 South by Southwest festival in Austin. But they soon discovered that demand for friendly, affordable accommodations provided by local residents existed year-round and nationwide—and even internationally.

Today, Airbnb is a giant enterprise active in 119 countries, where it lists over 500,000 properties ranging from studio apartments to actual castles and has served over ten million guests. In its last round of investment funding (April 2014), the company was valued at more than $10 billion—a level surpassed by only a handful of the world’s greatest hotel chains.

In less than a decade, Airbnb has siphoned off a growing segment of customers from the traditional hospitality industry—all without owning a single hotel room of its own.

It’s a tale of dramatic, unexpected change. Yet it’s only one in a series of improbable industry upheavals that share a similar DNA:

• Smartphone-based car service Uber was launched in a single city (San Francisco) in March 2009. Less than five years later, it was valued by investors at over $50 billion, and is poised to challenge or replace the traditional taxi business in many of the more than 200 global cities it operates in—all without owning a single car.

• China-based retailing giant Alibaba features nearly a billion different products on just one of its many business portals (Taobao, a consumer-to-consumer marketplace similar to eBay) and has been dubbed by The Economist “the world’s biggest bazaar”—all without owning a single item of inventory.

• With over 1.5 billion subscribers visiting regularly to read news, look at photos, listen to music, and watch videos, Facebook garners an estimated $14 billion in annual advertising revenue (2015) and is arguably the world’s biggest media company—all without producing a single piece of original content.

How can a major business segment be invaded and conquered in a matter of months by an upstart with none of the resources traditionally deemed essential for survival, let alone market dominance? And why is this happening today in one industry after another?

The answer is the power of the platform—a new business model that uses technology to connect people, organizations, and resources in an interactive ecosystem in which amazing amounts of value can be created and exchanged. Airbnb, Uber, Alibaba, and Facebook are just four examples from a list of disruptive platforms that includes Amazon, YouTube, eBay, Wikipedia, iPhone, Upwork, Twitter, KAYAK, Instagram, Pinterest, and dozens more. Each is unique and focused on a distinctive industry and market. And each has harnessed the power of the platform to transform a swath of the global economy. Many more comparable transformations are on the horizon.

The platform is a simple-sounding yet transformative concept that is radically changing business, the economy, and society at large. As we’ll explain, practically any industry in which information is an important ingredient is a candidate for the platform revolution. That includes businesses whose “product” is information (like education and media) but also any business where access to information about customer needs, price fluctuations, supply and demand, and market trends has value—which includes almost every business.

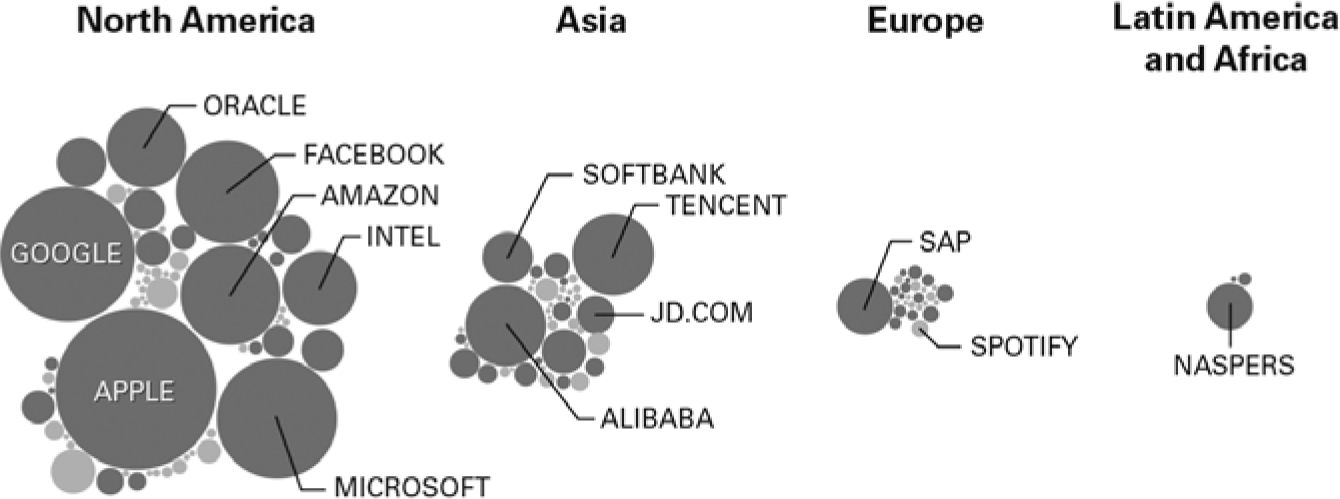

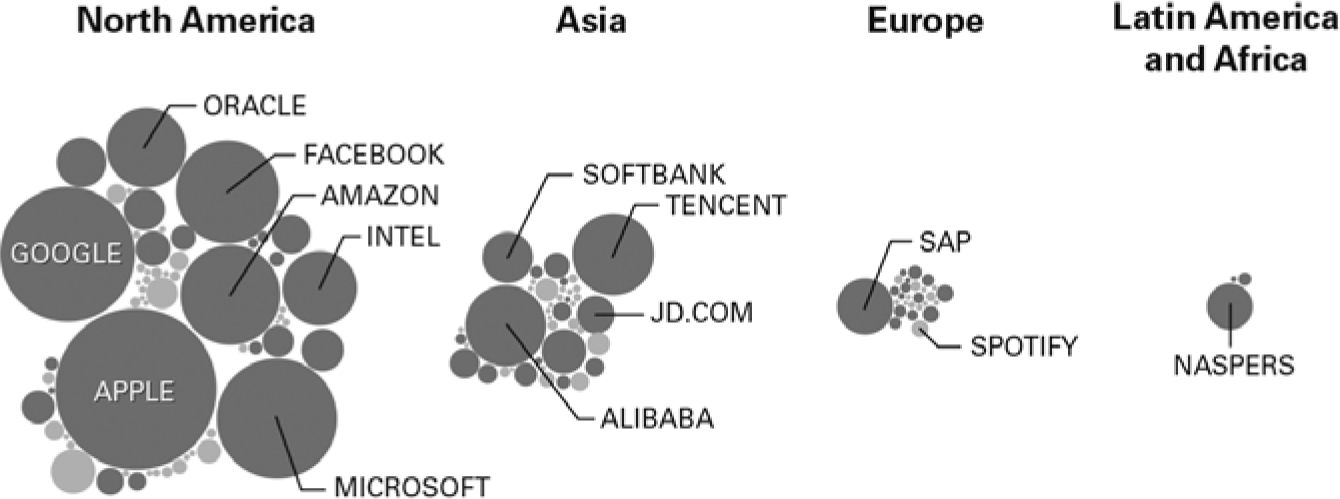

So perhaps it’s no wonder that the list of fastest-growing global brands is increasingly dominated by platform businesses. In fact, in 2014, three of the world’s five largest firms as measured by market capitalization—Apple, Google, and Microsoft—all run platform business models. One of these, Google, debuted as a public company in 2004. Another, Apple, nearly went bankrupt a few years earlier—when it still ran a closed business model rather than a platform. Now incumbent giants from Walmart and Nike to John Deere, GE, and Disney are all scrambling to adopt the platform approach to their businesses. To varying degrees, platform businesses are claiming a large and growing share of the economy in every region of the world (see Figure 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1. North America has more platform firms creating value, as measured by market capitalization, than any other region in the world. Platform firms in China, with its large, homogeneous market, are growing fast. Platform businesses in Europe, with its more fragmented market, have less than a quarter the value of such firms in North America, and the developing regions of Africa and Latin America are not far behind. Source: Peter Evans, Center for Global Enterprise.

The disruptive power of platforms is also transforming the lives of individuals in ways that would have been impossible a few years ago:

• Joe Fairless was a New York advertising executive who dabbled in real estate investing on the side. Teaching a real estate class on Skillshare, an education platform, introduced Joe to hundreds of eager young investors and helped him hone his speaking skills—enabling him to raise over a million dollars to launch his own investment firm and quit the ad business.

• Taran Matharu was a twenty-two-year-old business student living in London when he decided to write a book during the annual Novel Writing Month challenge. He posted excerpts on Wattpad, a story-sharing platform, and quickly attracted over five million readers. His first novel, Summoner, is being published in Britain and ten other countries, and Matharu is a full-time author.

• James Erwin was a software manual writer in Des Moines, Iowa, as well as a history buff. Browsing the community-based news platform Reddit one afternoon, he spotted a question about what would happen if a battalion of modern U.S. Marines took on the ancient Roman Empire. His typed response attracted eager followers and, within weeks, a movie deal. Erwin has now left his job to devote himself to screenwriting.

Teacher or lawyer, photographer or scientist, plumber or therapist—no matter what kind of work you do, the chances are good that a platform is poised to transform it, creating new opportunities and, in some cases, daunting new challenges.

The platform revolution is here—and the world it is ushering in is here to stay. But what exactly is a platform? What makes it unique? And what accounts for its remarkable transformative power? These are questions we’ll begin to explore in the remainder of this chapter.

Let’s start with a basic definition. A platform is a business based on enabling value-creating interactions between external producers and consumers. The platform provides an open, participative infrastructure for these interactions and sets governance conditions for them. The platform’s overarching purpose: to consummate matches among users and facilitate the exchange of goods, services, or social currency, thereby enabling value creation for all participants.

Broken down in this way, the workings of platforms may seem simple enough. Yet today’s platforms, empowered by digital technology that annihilates barriers of time and space, and employing smart, sophisticated software tools that connect producers and consumers more precisely, speedily, and easily than ever before, are producing results that are little short of miraculous.

THE PLATFORM REVOLUTION

AND THE SHAPE OF CHANGE

To understand the powerful forces that are being unleashed by the explosion of platform businesses, it helps to think about how value has long been created and transferred in most markets. The traditional system employed by most businesses is one we describe as a pipeline. By contrast with a platform, a pipeline is a business that employs a step-by-step arrangement for creating and transferring value, with producers at one end and consumers at the other. A firm first designs a product or service. Then the product is manufactured and offered for sale, or a system is put in place to deliver the service. Finally, a customer shows up and purchases the product or service. Because of its simple, single-track shape, we may also describe a pipeline business as a linear value chain.

In recent years, more and more businesses are shifting from the pipeline structure to the platform structure. In this shift, the simple pipeline arrangement is transformed into a complex relationship in which producers, consumers, and the platform itself enter into a variable set of relationships. In the world of platforms, different types of users—some of them producers, some of them consumers, and some of them people who may play both roles at various times—connect and conduct interactions with one another using the resources provided by the platform. In the process, they exchange, consume, and sometimes cocreate something of value. Rather than flowing in a straight line from producers to consumers, value may be created, changed, exchanged, and consumed in a variety of ways and places, all made possible by the connections that the platform facilitates.

Every platform operates differently, attracts different kinds of users, and creates different forms of value, but these same basic elements can be recognized in every platform business. In the mobile phone industry, for example, there are currently two major platforms—Apple’s iOS and the Google-sponsored Android. Consumers who sign up for one of these platforms can consume value provided by the platform itself—for example, the image-making capability provided by the phone’s built-in camera. But they can also consume value supplied by a set of developers who produce content for the platform to extend its functionality—for example, the value provided by an app that users access through Apple’s iPhone. The result is an exchange of value that is made possible by the platform itself.

In itself, the shift from the traditional linear value chain to the complex value matrix of a platform may sound reasonably straightforward. But its implications are staggering. The spread of the platform model into one industry after another is causing a series of revolutionary changes in almost every aspect of business. Let’s consider a few of these changes.

Platforms beat pipelines because platforms scale more efficiently by eliminating gatekeepers. Until recently, most businesses were built around products, which were designed and made at one end of the pipeline and delivered to consumers at the other end.* Today, plenty of pipeline-based businesses still exist—but when platform-based businesses enter the same marketplace, the platforms virtually always win.

One reason is that pipelines rely on inefficient gatekeepers to manage the flow of value from the producer to the consumer. In the traditional publishing industry, editors select a few books and authors from among the thousands offered to them and hope the ones they choose will prove to be popular. It’s a time-consuming, labor-intensive process based mainly on instinct and guesswork. By contrast, Amazon’s Kindle platform allows anyone to publish a book, relying on real-time consumer feedback to determine which books will succeed and which will fail. The platform system can grow to scale more rapidly and efficiently because the traditional gatekeepers—editors—are replaced by market signals provided automatically by the entire community of readers.

The elimination of gatekeepers also allows consumers greater freedom to select products that suit their needs. The traditional model of higher education forces students and their parents to purchase one-size-fits-all bundles that include administration, teaching, facilities, research, and much more. In their role as gatekeepers, universities can require families to buy the entire package because it is the only way they can get the valuable certification that a degree offers. However, given the choice, many students would likely be selective in the services they consume. Once there is an alternate certification that employers are willing to accept, universities will find it increasingly challenging to maintain the bundle. Unsurprisingly, developing such an alternate certification is among the primary goals of platform education firms such as Coursera.

Consulting and law firms are also in the business of selling bundles. Firms might be willing to pay high prices for the services of experts. In order to gain access, they must also purchase the services of relatively junior staff at high markups. In the future, the most talented lawyers and consultants might work individually with firms and transact across a platform that can supply the back office and lower-level services once provided by a law or consulting firm. Platforms like Upwork are already making professional services available to prospective employers while eliminating the bundling effect imposed by traditional gatekeepers.

Platforms beat pipelines because platforms unlock new sources of value creation and supply. Consider how the hotel industry has traditionally worked. Growth required hospitality firms like Hilton or Marriott to add additional rooms to sell through their existing brands using sophisticated back-office reservation and payments systems. This means continually scouting the real estate markets for promising territories, investing in existing properties or building new ones, and spending large sums to maintain, upgrade, expand, and improve them.

Upstart Airbnb is, in one sense, in the same business as Hilton or Marriott. Like the hotel giants, it uses refined pricing and booking systems designed to allow guests to find, reserve, and pay for rooms as they need them. But Airbnb applies the platform model to the hotel business: Airbnb doesn’t own any rooms. Instead, it created and maintains the platform that allows individual participants to provide the rooms directly to consumers. In return, Airbnb takes a 9–15 percent (average 11 percent) transaction fee for every rental arranged through the platform.1

One implication is that growth can be much faster for Airbnb or any rival platform than for a traditional hotel company since growth is no longer constrained by the ability to deploy capital and manage physical assets. It may take years for a hotel chain to select and purchase a new piece of real estate, design and build a new resort, and hire and train staff. By contrast, Airbnb can increase its “inventory” of properties as quickly as it can sign up users with spare rooms to rent. As a result, in just a few years, Airbnb has achieved a scope and value that a traditional hotelier can hope to reach only after decades of often risky investment and hard work.

In platform markets, the nature of supply changes. Supply now unlocks spare capacity and harnesses contributions from the community which used to be only a source of demand. Whereas the leanest traditional businesses ran on just-in-time inventory, new organizational platforms run on not-even-mine inventory. If Hertz could deliver a car to an airport just as the plane arrived, it ran as well as could be expected. Now RelayRides borrows the car of a departing traveler in order to loan it to an arriving traveler. The person who used to pay to park an empty car now gets paid, complete with insurance, to let others use it. Everyone wins except Hertz and the other traditional car rental companies. TV stations built studios and hired staff to produce video. YouTube, operating a different business model, has more viewers than any station, and it uses content produced by the people who watch it. Everyone wins except the TV networks and movie studios that once had a near-monopoly on video production. Singapore-based Viki is challenging the traditional media value chain by using an open community of translators to add subtitles to Asian movies and soap operas. Viki then licenses the subtitled videos to distributors in other countries.

Thus, platforms disrupt the traditional competitive landscape by exposing new supply to the market. Hotels that must cover fixed costs find themselves competing with firms that have no fixed costs. This works for the new firms because there is spare capacity that can be brought to market through the assistance of the platform intermediary. The sharing economy is built on the idea that many items, such as automobiles, boats, and even lawnmowers, sit idle most of the time. Before the rise of the platform, it might have been possible to loan something to a family member, close friend, or neighbor, but much harder to loan to a stranger. This is because it would be difficult to trust that your home would be left in good shape (Airbnb), your car would be returned undamaged (RelayRides), or your lawnmower would come back (NeighborGoods).

The effort necessary to individually verify credit- and trustworthiness is an example of the high transaction costs that used to prevent exchange. By providing default insurance contracts and reputation systems to encourage good behavior, platforms dramatically lower transaction costs and create new markets as new producers start producing for the first time.

Platforms beat pipelines by using data-based tools to create community feedback loops. We’ve seen how the Kindle platform relies on reactions from the community of readers to determine which books will be widely read and which will not. Platforms of all kinds rely on similar feedback loops. Platforms like Airbnb and YouTube use such feedback loops to compete with traditional hotels and television channels. As these platforms gather community signals about the quality of content (in the case of YouTube) or the reputation of service providers (on Airbnb), subsequent market interactions become increasingly efficient. Feedback from other consumers makes it easy to find videos or rental properties that are likely to suit your needs. Products that receive overwhelmingly negative feedback usually disappear from the platform completely.

By contrast, traditional pipeline firms rely on mechanisms of control—editors, managers, supervisors—to ensure quality and shape market interactions. These control mechanisms are costly and inefficient to grow to scale.

Wikipedia’s success demonstrates that platforms can leverage community feedback to replace a traditional supply chain. Reference works like the venerable Encyclopaedia Britannica were once created through costly, complex, difficult-to-manage centralized supply chains of academic experts, writers, and editors. Using the platform model, Wikipedia has built an information source comparable to Britannica in quality and scope by leveraging a community of external contributors to grow and police the content.

Platforms invert the firm. Because the bulk of a platform’s value is created by its community of users, the platform business must shift its focus from internal activities to external activities. In the process, the firm inverts—it turns inside out, with functions from marketing to information technology to operations to strategy all increasingly centering on people, resources, and functions that exist outside the business, complementing or replacing those that exist inside a traditional business.

The language used to describe this process of inversion differs from one business function to another. In marketing, for example, Rob Cain, the CIO of Coca-Cola, notes that the key terms used to define systems of message delivery have shifted from broadcast to segmentation, and then to virality and social influence; from push to pull; and from outbound to inbound. All these terminological changes reflect the fact that marketing messages once disseminated by company employees and agents now spread via consumers themselves—a reflection of the inverted nature of communication in a world dominated by platforms.2

Similarly, information technology systems have evolved from back-office enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems to front-office consumer relationship management (CRM) systems and, most recently, to out-of-the-office experiments using social media and big data—another shift from inward focus to outward focus. Finance is shifting its focus from shareholder value and discounted cash flows of assets owned by the firm to stakeholder value and the role of interactions that take place outside the firm.

Operations management has likewise shifted from optimizing the firm’s inventory and supply chain systems to managing external assets the firm doesn’t directly control. Tom Goodwin, senior vice president of strategy for Havas Media, describes this change succinctly: “Uber, the world’s largest taxi company, owns no vehicles. Facebook, the world’s most popular media owner, creates no content. Alibaba, the most valuable retailer, has no inventory. And Airbnb, the world’s largest accommodation provider, owns no real estate.”3 The community provides these resources.

Strategy has moved from controlling unique internal resources and erecting competitive barriers to orchestrating external resources and engaging vibrant communities. And innovation is no longer the province of in-house experts and research and development labs, but is produced through crowdsourcing and the contribution of ideas by independent participants in the platform.

External resources don’t completely replace internal resources—more often they serve as a complement. But platform firms emphasize ecosystem governance more than product optimization, and persuasion of outside partners more than control of internal employees.

THE PLATFORM REVOLUTION:

HOW WILL YOU RESPOND?

As you’ll see in this book, the rise of the platform is driving transformations in almost every corner of the economy and of society as a whole, from education, media, and the professions to health care, energy, and government. Figure 1.2 is a necessarily incomplete table of some notable current arenas of platform activity, along with examples of some of the platform enterprises at work in those industry sectors. Note that platforms are continually evolving, that many platforms serve more than one purpose, and that new platform companies are appearing every day. Many of the businesses listed here are likely to be familiar to you; some may not be. The stories behind a number of them will be recounted in this book. Our goal here is to provide not a comprehensive or systematic overview but simply a sketch which we hope will convey the growing scope and importance of platform companies on the world stage.

INDUSTRY |

EXAMPLES |

Agriculture |

John Deere, Intuit Fasal |

Communication and Networking |

LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter, Tinder, Instagram, Snapchat, WeChat |

Consumer Goods |

Philips, McCormick Foods FlavorPrint |

Education |

Udemy, Skillshare, Coursera, edX, Duolingo |

Energy and Heavy Industry |

Nest, Tesla Powerwall, General Electric, EnerNOC |

Finance |

Bitcoin, Lending Club, Kickstarter |

Health Care |

Cohealo, SimplyInsured, Kaiser Permanente |

Gaming |

Xbox, Nintendo, PlayStation |

Labor and Professional Services |

Upwork, Fiverr, 99designs, Sittercity, LegalZoom |

Local Services |

Yelp, Foursquare, Groupon, Angie’s List |

Logistics and Delivery |

Munchery, Foodpanda, Haier Group |

Media |

Medium, Viki, YouTube, Wikipedia, Huffington Post, Kindle Publishing |

Operating Systems |

iOS, Android, MacOS, Microsoft Windows |

Retail |

Amazon, Alibaba, Walgreens, Burberry, Shopkick |

Transportation |

Uber, Waze, BlaBlaCar, GrabTaxi, Ola Cabs |

Travel |

Airbnb, TripAdvisor |

FIGURE 1.2. Some of the industry sectors currently being transformed by platform businesses, along with examples of platform companies working in those arenas.

Figure 1.2 also suggests the remarkable diversity of platform businesses. At a glance, there doesn’t seem to be much that companies like Twitter and General Electric, Xbox and TripAdvisor, Instagram and John Deere all have in common. Yet all are operating businesses that share the fundamental platform DNA—they all exist to create matches and facilitate interactions among producers and consumers, whatever the goods being exchanged may be.

As a result of the rise of the platform, almost all the traditional business management practices—including strategy, operations, marketing, production, research and development, and human resources—are in a state of upheaval. We are in a disequilibrium time that affects every company and individual business leader. The coming of the world of platforms is a major reason why.

Consequently, platform expertise has now become an essential attribute for business leadership. Yet most people—including many business leaders—are still struggling to come to grips with the rise of the platform.

In the chapters that follow, we’ll provide a comprehensive guide to the platform business model and its growing impact on practically every sector of the economy. The insights we’ll share are based on extensive research as well as our experience as consultants working with platform businesses large and small, in a wide range of industries and nonprofit arenas in countries around the world.

You’ll learn precisely how platforms work, the varying structures they assume, the numerous forms of value they create, and the almost limitless range of users they serve. If you’re interested in starting your own platform business—or in modifying an existing organization to take advantage of the power of the platform—this book will serve as a manual to help you navigate the complexities of designing, launching, managing, governing, and growing a successful platform. And if running a platform business isn’t for you, you’ll learn how the growing impact of platforms is likely to affect you as a businessperson, a professional, a consumer, and a citizen—and how you can participate happily (and profitably) in an economy increasingly dominated by platforms of every type.

No matter what role you play in today’s rapidly changing economy, now is the time for you to master the principles of the world of platforms. Turn the page, and we’ll help you do just that.

TAKEAWAYS FROM CHAPTER ONE

A platform’s overarching purpose is to consummate matches among users and facilitate the exchange of goods, services, or social currency, thereby enabling value creation for all participants.

A platform’s overarching purpose is to consummate matches among users and facilitate the exchange of goods, services, or social currency, thereby enabling value creation for all participants.

Because platform businesses create value using resources they don’t own or control, they can grow much faster than traditional businesses.

Because platform businesses create value using resources they don’t own or control, they can grow much faster than traditional businesses.

Platforms derive much of their value from the communities they serve.

Platforms derive much of their value from the communities they serve.

Platforms invert companies, blurring business boundaries and transforming firms’ traditional inward focus into an outward focus.

Platforms invert companies, blurring business boundaries and transforming firms’ traditional inward focus into an outward focus.

The rise of the platform has already transformed many major industries—and more, equally important transformations are on the way.

The rise of the platform has already transformed many major industries—and more, equally important transformations are on the way.

* For simplicity’s sake, we refer here to both products and services as “products.” The main difference between the two is that products are tangible, physical objects, while services are intangible and delivered through activities. In traditional businesses, both are delivered through linear value chains—pipelines—which justifies our lumping them together in this discussion.